Abstract

Purpose

Previous studies have addressed post-operative pain management after ACL reconstruction by examining the use of intra-articular analgesia and/or modification of anesthesia techniques. To our knowledge, however, no previous studies have evaluated the effect of zolpidem on post-operative narcotic requirements, pain, and fatigue in patients undergoing outpatient arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. The purpose of this prospective, blinded, randomized, controlled clinical study was to evaluate the effect of zolpidem on post-operative narcotic requirements, pain, and fatigue in patients undergoing outpatient arthroscopic ACL reconstruction.

Methods

Twenty-nine patients undergoing arthroscopic ACL reconstruction were randomized to a treatment group or placebo group. Both groups received post-operative hydrocodone/acetaminophen bitartrate (Vicodin ES). Patients in the treatment group received a single dose of zolpidem for the first seven post-operative nights. Patients in the placebo group received a gelatin capsule similar in appearance to zolpidem. The amount of Vicodin used in each group, the amount of post-operative pain, and the amount of post-operative fatigue were analyzed.

Results

Following ACL reconstruction, a 28% reduction was seen in the total amount of narcotic consumed with zolpidem (P = 0.047) when compared to placebo. There were no significant differences in post-operative pain or fatigue levels between zolpidem and placebo.

Conclusion

Adding zolpidem to the post-operative medication regimen after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction helps to lower the amount of narcotic pain medication required for adequate analgesia.

Level of evidence

Randomized controlled clinical trial, Level I.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Post-operative pain is the most commonly reported concern after ambulatory arthroscopic surgery, with moderate to severe pain occurring in approximately 30% of individuals [7]. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, historically involving inpatient admission post-operatively, is increasingly being done on an outpatient basis [11, 19, 20, 26, 28]. Outpatient ACL reconstruction has been shown to be preferred by patients, and is associated with an earlier return to work [31]. Therefore, effective post-operative pain management is an important component of recovery following outpatient anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. The causes for post-operative pain are many including pre-operative pain levels, surgical technique, and rehabilitation protocol [2, 24]. The methods of controlling pain for outpatient ACL reconstruction are multimodal and focus on preemptive (local anesthetic infiltration, femoral nerve blocks), intraoperative (intra-articular injection), and post-operative modalities (oral opioids, cryotherapy, analgesia infusion catheters, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) [1, 5, 6, 8, 12, 21, 23, 25].

The post-operative period has been associated with both difficulty falling asleep and reduced duration of sleep [4]. In addition, sleep deprivation has been associated with increased sensitivity to pain in both human and animal studies [13, 22]. The use of zolpidem, a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic sleep-aid, to reduce patient’s narcotic consumption, fatigue level, and post-operative pain following knee arthroscopy has previously been documented [27]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of zolpidem on narcotic consumption, pain, and fatigue following ACL reconstruction, a more complicated procedure which generally involves more pain and fatigue than knee arthroscopy post-operatively. The effect of zolpidem use in a multimodal approach to pain control following ACL reconstruction has not been previously documented. The hypothesis was that patients receiving zolpidem will require less narcotic pain medication and will have lower pain and fatigue scores, as defined by visual analog scales, than patients receiving placebo.

Materials and methods

Hospital investigational review board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to initiation of the study from the IRB at Rhode Island Hospital. All patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction, who had already completed a course of physical therapy and presented with full range of motion of the injured knee, were evaluated for participation in the study. The indications for surgical intervention in these patients included anterior knee laxity on physical exam and MRI consistent with complete ACL rupture. Any patients requiring multiple ligament reconstructions were excluded.

The goals of the study were explained to patients at the pre-operative appointment, and the option to participate in this study was presented. A total of 29 patients, from the practice of one surgeon, agreed to participate and were enrolled into the study. Informed consent was obtained and patients were given instructions on how to properly complete the daily post-operative questionnaire for pain and fatigue.

All patients underwent a standardized surgical protocol in which surgical time was similar for all patients. In each case, a femoral nerve block was administered by the Department of Anesthesia. A tourniquet was placed to 250 mm Hg and was later released after dressing placement. A two portal technique was used. During final fixation on the tibial side, the tibia was reduced and the knee was in approximately 20 degrees of flexion. The grafts were then evaluated and there was full range of motion without pathologic graft motion. Intra-articular Marcaine (<20 cc) was given to further augment post-operative pain control. An immobilizer with ice packs was applied. TEDS anti-embolism stockings were applied.

A standardized instruction booklet outlining specific post-operative care was given to each patient and reviewed preoperatively in the office, in the recovery room, and reviewed a third time by the office nurse 3 days after surgery. This booklet reviews the 20 min of ice used every hour, correct elevation techniques (above the level of the heart), the use of crutches for the first 5 days in a touchdown weight-bearing capacity, and gentle isometric muscle strengthening and range of motion to comfort exercises. All patients were given crutches after surgery. All patients were discharged to home the day of surgery.

On the day of surgery, all patients received a prescription for 40 hydrocodone/acetaminophen bitartrate (Vicodin ES or Hydrocodone ES—Abbott Laboratories, Chicago IL, US) tablets (7.5 mg/750 mg). The treatment group received 7 zolpidem tartrate (Ambien—Sanofi-Aventis, Bridgewater NJ, US) tablets (10 mg) and the placebo group was given 7 gelatin pills, to be taken for the first 7 post-operative days. Patients in both groups were expected to take the zolpidem or placebo pills nightly, whereas the Vicodin was written to be taken 1–2 tabs po q 6 h as needed. Prior to initiation of the study, the zolpidem and placebo pills had been placed into pill bottles by the hospital pharmacy. Each had been formulated such that the pills and bottles looked identical. Each pill bottle, whether zolpidem or placebo, was assigned a number in order to reference to at the end of the study. Only the pharmacy was aware which numbers corresponded to placebo versus zolpidem. The bottle numbers were randomly assigned to a patient’s medical record number by a research assistant in the surgeon’s office once the patient had agreed to participate in the study. The bottles were then appropriately given to the patient on the day of surgery. The patient, the treating surgeon, and the outcome assessors were not aware of the group assignment of the patient. A total 13 of patients were entered into the treatment group and 16 patients were entered into the placebo group.

In addition to zolpidem and vicodin, the authors routinely add ibuprofen to the post-operative regimen for pain control, in an effort to minimize narcotic consumption. In an effort to better solely analyze the role of zolpidem on narcotic consumption, pain levels, and fatigue levels, patients were also subdivided into groups receiving ibuprofen and not receiving ibuprofen. For the first half of the study period all patients received a prescription for ibuprofen (800 mg), to be taken every 8 h as needed. No patients received a prescription for ibuprofen in the second half of the study period. In total, 6 patients in the treatment group received ibuprofen, while 7 in the placebo group received ibuprofen.

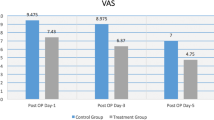

On the day of surgery, patients were given the questionnaire to evaluate their pain and fatigue levels and were re-instructed on how to properly complete the form. The questionnaire consisted of a series of standard visual analog scales (VAS) for both pain and fatigue levels along with space to record the amount of pain medication that was consumed over the course of 7 days. Twice a day (once in the morning and once in the evening), each patient was asked to record their perceived level of pain and fatigue on the visual analog scales. A zero corresponded to “no pain” or “no fatigue,” whereas a ten represented “unbearable pain” or “fatigue as bad is it can be.” Patients were also asked to record the number of hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin ES) and ibuprofen pills they consumed each day.

The questionnaire allowed us to record values for the total amount of Vicodin consumed (TOT VIC), the average amount of Vicodin consumed each day (AVG VIC), the total amount of ibuprofen consumed (TOT IBP), the average amount of ibuprofen consumed each day (AVG IBP), total pain (TOT PAIN), morning pain (AM PAIN), evening pain (PM PAIN), total fatigue (TOT FAT), morning fatigue (AM FAT), and evening fatigue (PM FAT).

Baseline demographics, physical exam findings, surgical findings, and pre-operative MRI findings were recorded from the medical record for each patient at the conclusion of the study. Baseline demographics recorded include age, sex, worker’s compensation claims for the ACL injury, smoking history, alcohol use, previous surgeries on the same knee, and athletic activity level. Variables recorded from the physical exam include presence of effusion, joint line tenderness, locking, and instability. Surgical findings recorded include concomitant meniscal tears, debridement or repair of meniscus, degree of chondrosis, chondroplasty, and loose body removal. Pre-operative MRI findings documented include ACL tear and concomitant meniscal tears.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using two-way analysis of variance. The main effects evaluated two factors: (1) treatment (zolpidem vs. placebo) and (2) ibuprofen (yes vs. no). A significant interaction between treatment and ibuprofen would indicate that the treatment effect was ibuprofen-dependent. When significant main effects or interactions were found, pair-wise comparisons were performed between experimental groups using the Holm-Sidak method. The dependent outcome variables analyzed in this fashion were TOT VIC, AVG VIC, TOT PAIN, AM PAIN, PM PAIN, TOT FAT, AM FAT, and PM FAT. Baseline demographics, physical exam findings, surgical findings, and pre-operative MRI findings between the two treatment groups were analyzed. A P value <0.05 was defined as significant.

Results

A total of 29 patients were recruited into this study; 13 patients in the treatment group and 16 patients in the placebo group. The average age of all patients in the study was 36.2, with an average of 36.9 in the treatment group versus 35.6 in the placebo group. There were 14 females and 15 males (5 females, 8 males in treatment group; 9 females, 7 males in placebo group). The study included 7 patients (24%) involved in worker’s compensation claims (3 in treatment group; 4 in placebo group) and 3 patients (10%) were smokers (1 in treatment group; 2 in placebo group). Statistical analysis of baseline demographics (age, sex, worker’s compensation claims for the ACL injury, smoking history, alcohol use, previous surgeries on the same knee, athletic activity level), physical exam findings (effusion, joint line tenderness, locking, and instability), surgical findings (concomitant meniscal tears, debridement or repair of meniscus, degree of chondrosis, chondroplasty, and loose body removal), and pre-operative MRI findings (concomitant meniscal tears) demonstrated no significant differences between the two treatment groups. There were no adverse medication events.

Following ACL reconstruction, a 28% reduction was seen in the total amount of Vicodin consumed with zolpidem when compared to placebo (Fig. 1). The findings for average amount of Vicodin mirrored those for total amount of Vicodin. The treatment effect was not ibuprofen-dependent. For all other outcome variables (TOT PAIN, AM PAIN, PM PAIN, TOT FAT, AM FAT, and PM FAT), there were no significant differences between the experimental groups (Table 1).

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that the use of zolpidem as part of a multimodal post-operative medication regimen following outpatient arthroscopic ACL reconstruction helps to lower the amount of narcotic pain medication required for adequate analgesia.

In 2001, pain was named the “sixth vital sign” by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, and documentation of post-operative pain assessment by health care providers is now a required feature of medical records [27]. The ability to perform ACL reconstruction as an outpatient procedure reduces consumption of hospital resources and saves an average of $5,000 per case [3, 18]. However, post-operative pain management following outpatient ACL surgery remains a challenge.

High post-operative pain levels have been correlated with clinically significant sleeping problems in patients undergoing elective outpatient surgery [17]. Induced REM sleep deprivation in a rat model demonstrated a significant increase in the behavioral responses to noxious mechanical, thermal, and electrical stimuli [4]. In the post-operative patient, pain can initiate a vicious cycle whereby discomfort affects a patient’s ability to sleep. The subsequent fatigue heightens the patient’s perception of pain leading to further sleep deprivation [13]. The ability of zolpidem to reduce narcotic consumption and fatigue has previously been demonstrated in patients undergoing knee arthroscopy [27].

The most common adverse effects reported with the short-term use of zolpidem are drowsiness, dizziness, and diarrhea [15]. One study, focused on the use of zolpidem in the elderly, found an increased risk of hip fracture [30]. Numerous other studies provide conflicting evidence regarding risk of addiction, lowering of seizure threshold, and tolerance effect [9, 10, 14–16, 29]. Although no patients in our study reported adverse events from the use of zolpidem, we recommend counseling patients about potential side effects.

The major limitation of this study is the size of the study groups. The overall size of the groups may have limited our ability to find differences between the use of zolpidem and placebo for post-operative pain and fatigue scores. It is possible that a larger sample size may have shown further differences.

Our study demonstrates that use of zolpidem significantly reduces hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin ES) consumption when compared to placebo in the post-operative setting after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. We did not find any additional differences in post-operative pain and fatigue scores between zolpidem and placebo after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. The patients undergoing outpatient arthroscopic ACL reconstruction are generally young, healthy individuals who are less at risk for serious side effects from zolpidem. This, coupled with the fact that we feel a reduction in narcotic medication requirements is of value, allows us to recommend that zolpidem be considered in the multimodal post-operative medication regimen of patients undergoing outpatient arthroscopic ACL reconstruction, who have no other contraindications to taking zolpidem.

Conclusion

Adding zolpidem to the post-operative medication regimen after outpatient arthroscopic ACL reconstruction helps to lower the amount of narcotic pain medication required for adequate analgesia. Zolpidem should be considered in a multimodal post-operative treatment regimen for pain relief following outpatient arthroscopic ACL reconstruction.

References

Alford JW, Fadale PD (2003) Evaluation of postoperative bupivacaine infusion for pain management after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 19:855–861

Andersson D, Samuelsson K, Karlsson J (2009) Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries with special reference to surgical technique and rehabilitation: an assessment of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy 25:653–685

Aronowitz ER, Kleinbart FA (1998) Outpatient ACL reconstruction using intraoperative local analgesia and oral postoperative pain medication. Orthopedics 21:781–784

Beliaev DG, Shestokov IP, Zadorozhnaia OA et al (1994) Insomnia and its treatment during the postoperative period. Anesteziol Reanimatol 1:37–40

Boonriong T, Tangtrakulwanich B, Glabglay P et al (2010) Comparing etoricoxib and celecoxib for preemptive analgesia for acute postoperative pain in patients undergoing arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11:246

Brandsson S, Rydgren B, Hedner T et al (1996) Postoperative analgesic effects of an external cooling system and intra-articular bupivacaine/morphine after arthroscopic cruciate ligament surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 4:200–205

Chauvin M (2003) State of the art of pain treatment following ambulatory surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol Suppl 28:3–6

Chew HF, Evans NA, Stanish WD (2003) Patient-controlled bupivacaine infusion into the infrapatellar fat pad after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 19:500–505

Cotroneo A, Gareri P, Nicoletti N et al (2007) Effectiveness and safety of hypnotic drugs in the treatment of insomnia in over 70-year old people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 44(Suppl):121–124

Cubala WJ, Landowski J (2007) Seizure following sudden zolpidem withdrawal. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31:539–540

Elgafy H, Elsafty M (1998) Day case arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J R Coll Surg Edinb 43:336–338

Fanton GS, Dillingham MF, Wall MS et al (2008) Novel drug product to improve joint motion and function and reduce pain after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 24:625–636

Hakki Onen S, Alloui A, Jourdan D et al (2001) Effects of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep deprivation on pain sensitivity in the rat. Brain Res 900:261–267

Hindmarch I, Legangneux E, Stanley N et al (2006) A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of the residual psychomotor and cognitive effects of zolpidem-MR in healthy elderly volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 62:538–545

Holm KJ, Goa KL (2000) Zolpidem: an update of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs 59:865–889

Huang MC, Lin HY, Chen CH (2007) Dependence on zolpidem. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 61:207–208

Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA (2003) Sleeping characteristics of adults undergoing outpatient elective surgery: a cohort study. J Clin Anesth 15:505–509

Kao JT, Giangarra CE, Singer G et al (1995) A comparison of outpatient and inpatient anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Arthroscopy 11:151–156

Krywulak SA, Mohtadi NG, Russell ML et al (2005) Patient satisfaction with inpatient versus outpatient reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: a randomized clinical trial. Can J Surg 48:201–206

Kumar A, Bickerstaff DR, Johnson TR et al (2001) Day surgery anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Sheffield experiences. Knee 8:25–27

McGuire DA, Sanders K, Hendricks SD (1993) Comparison of ketorolac and opioid analgesics in postoperative ACL reconstruction outpatient pain control. Arthroscopy 9:653–661

Onen SH, Alloui A, Gross A et al (2001) The effects of total sleep deprivation, selective sleep interruption and sleep recovery on pain tolerance thresholds in healthy subjects. J Sleep Res 10:35–42

Raynor MC, Pietrobon R, Guller U et al (2005) Cryotherapy after ACL reconstruction: a meta-analysis. J Knee Surg 18:123–129

Samuelsson K, Andersson D, Karlsson J (2009) Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries with special reference to graft type and surgical technique: an assessment of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy 25:1139–1174

Stalman A, Tsai JA, Wredmark T et al (2008) Local inflammatory and metabolic response in the knee synovium after arthroscopy or arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 24:579–584

Talwalkar S, Kambhampati S, De Villiers D et al (2005) Day case anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a study of 51 consecutive patients. Acta Orthop Belg 71:309–314

Tashjian RZ, Banerjee R, Bradley MP et al (2006) Zolpidem reduces postoperative pain, fatigue, and narcotic consumption following knee arthroscopy: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded study. J Knee Surg 19:105–111

Tierney GS, Wright RW, Smith JP et al (1995) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction as an outpatient procedure. Am J Sports Med 23:755–756

Victorri-Vigneau C, Dailly E, Veyrac G et al (2007) Evidence of zolpidem abuse and dependence: results of the French Centre for Evaluation and Information on Pharmacodependence (CEIP) network survey. Br J Clin Pharmacol 64:198–209

Wang PS, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ et al (2001) Zolpidem use and hip fractures in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:1685–1690

Weale AE, Ackroyd CE, Mani GV et al (1998) Day-case or short-stay admission for arthroscopic knee surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 80:146–149

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge that this study was completed with the assistance of an educational grant from Smith and Nephew. This was used to defray the pharmacy costs, including the zolpidem and placebo pills, and the preparation of the pills.

Conflict of interest

The authors wish to report that there are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors, their immediate families, or any research foundation related to the subject of this study.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board prior to initiation of the study. All persons involved in the study gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Clinical Relevance: This study demonstrates that zolpidem can be an A3 effective part of a multimodal post-operative treatment regimen for A4 pain relief following ACL reconstruction

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tompkins, M., Plante, M., Monchik, K. et al. The use of a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic sleep-aid (Zolpidem) in patients undergoing ACL reconstruction: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19, 787–791 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1368-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1368-x