Abstract

Purpose

High tibial osteotomy is a well-established method for the treatment of medial unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee.

Methods

We analysed retrospectively the long-term outcome of open and closing wedge valgisation high tibial osteotomies. Out of 71 patients, 54 (76%) were available for the study. Survival rates and the influence of the osteotomy type were investigated. Secondary outcome measures were the course of radiological leg axis and osteoarthritis as well as score outcomes.

Results

During a median follow-up of 16.5 years (IQR 14.5–17.9; range 13–21), 13 patients (24%) underwent conversion to total knee arthroplasty; the other 41 patients (76%, survivor group) were studied by score follow-up as well as clinical and radiological examinations. Osteotomy survival was of 98% after 5 years, 92% after 10 years and 71% after 15 years. Comparison between open and closing wedge high tibial osteotomy showed no significant difference in survival and score outcome. The median Visual Analogue Score (VAS) was 0 (IQR 0–1; range 0–4), the Satisfaction Index was 80% (IQR 63–89; range 30–100), the median Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score was 71 (IQR 49–82; range 9–100) and the median Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis index was 84 (IQR 66–96; range 9–100). Radiological evaluation showed only a slight progression of the degree of osteoarthritis following the Kellgren and Lawrence classification. In each case, the axis passed through the healthy compartment or at least through the centre of the knee.

Conclusion

Open and closing wedge high tibial osteotomies are a successful choice of treatment for unicompartmental degenerative diseases with associated varus in active patients. Survival of both techniques is comparable in our series and is associated with low pain scores, high satisfaction and high activity levels of the survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

High tibial osteotomies are safe, effective and well-established surgical techniques for the treatment of medial unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee with associated varus alignment. The aim of these procedures is to transfer the mechanical load axis from the damaged knee compartment to the intact knee compartment. Different surgical techniques for osteotomies have been described, whereas during the period of the present study (1980s and 1990s) mainly high tibial closing wedge osteotomies were carried out for valgisation [7]. Correction of the mechanical load axis leads to a regenerative process of the involved compartment, with reduction of subchondral sclerosis [2, 32], and spontaneous regeneration of cartilage [8, 10, 17, 24, 25, 35].

There is a broad consensus that clinical results 5–10 years after osteotomy are good but that they deteriorate with time, as reported by Bonnin in a literature analysis [6]. Coventry et al. reported osteotomy survival of 87% after 5 years and 66% after 10 years [8], and Naudie reported osteotomy survival of 73% after 5 years, 51% after 10 years, 39% after 15 years and 31% after 20 years [23]. The fact that results tend to deteriorate with time (particularly after 15 years) has been confirmed in other studies [3, 5, 18, 26, 29, 37].

The aim of the present retrospective study is to present the long-term osteotomy survival and outcome for a consecutive series of patients with valgus osteotomies that were fixed with stable implants around the knee for medial unicompartmental osteoarthritis. We investigated whether survival of open and closing wedge high tibial osteotomies differ from each other and if the outcome in our series was comparable to the literature.

Materials and methods

The present study was conducted as a retrospective clinical and radiographic review for a consecutive series of patients who underwent surgery at the University Hospital of Berne (Switzerland) by the senior author (RPJ) from 1984 to 1992. Each patient who underwent a frontal plane valgisation osteotomy of the proximal tibia during this period was included; none were excluded. Indications for osteotomies were symptomatic medial unicompartmental degenerative diseases of the knee with an associated varus alignment.

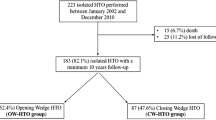

Seventy-one patients with 72 valgisation osteotomies were identified. Fifty-four patients were available for telephone survey of which 13 (13 knees) were converted to total knee arthroplasty. The 41 osteotomy survivors were available for score follow-up and 29 subjects were additionally available for radiological and clinical examination (Fig. 1).

Open and closing wedge technique osteotomy was performed proximally to the tibial tuberosity. Closing wedge osteotomy was done by a modified Weber technique with a step cut osteotomy to the proximal fibula. Fixation is assured with a bent one-half tubular plate and two screws [22, 36]. Open wedge osteotomy was performed by a release of the medial collateral ligament. An autologous tricortical bone graft from the iliac crest was inserted into the osteotomy gap and stabilised with a plate. An additional knee arthroscopy was not systematically carried out. Postoperatively, the patients were allowed full motion with partial weight bearing (15 kg) in a removable splint for six to eight weeks until osteotomy consolidation.

By means of a telephone survey, patients were interviewed and divided into two groups: osteotomy survivors and patients converted to total knee arthroplasty. For the latter group, the length of time between the osteotomy and the conversion was recorded. The survival analysis according to the Kaplan–Meier method was considered to be the primary endpoint, with conversion to total knee arthroplasty as the endpoint. All remaining patients (survivors) were invited to a clinical and a radiological investigation.

Survivors were scored according to the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) at follow-up [27]. KOOS includes the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) [4] and can therefore be calculated. Further outcome measurements were the Visual Analogue Scale (0–10) [14] and the Satisfaction Index (0% = minimal satisfaction, 100% = maximal satisfaction). Patients were asked about their activity during work and sport and were divided into six activity groups (Table 1), and their body mass index (BMI) calculated.

The range of motion and effusion were determined on clinical examination.

Radiological investigation at the time of review consisted of standard weight-bearing anteroposterior radiographs and lateral radiographs of the knee, as well as a weight-bearing full-leg length view. These images were compared with preoperative and postoperative radiographs, and the degree of osteoarthritis according to the classification of Kellgren and Lawrence determined and compared [16]. The passage of the mechanical load axis in the knee was evaluated according to Fujisawa, whereby 0% represents the centre of the knee and 100% the medial or lateral border of the tibia [10]. Measurements have been taken by three of the authors independently. Maximal intraobserver measurement deviation was for the Fujisawa scale 5% and for the Kellgren and Lawrence classification one degree. The average value was taken in these cases.

Statistical analysis

Data are the median with interquartile range (IQR) and range. Survival analysis was calculated according to the Kaplan–Meier method with confidence intervals of 95%. Significance was calculated with the Mann–Whitney test or the Log-rank test, considering P < 0.05 as significant. Calculations and illustrations were done with MedCalc® Software (version 10.4.8.0; Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

The median age of the osteotomy survivors at surgery was 40 years (IQR 31–58; range 15–68) and at follow-up 58.5 years (IQR 50–73; range 35–87). Thirty-seven patients were men and 17 were women; 29 knees were left-sided and 26 were right-sided. The median period of follow-up after surgery of the 54 available patients was 16.5 years (IQR 14.5–17.9; range 13.0–21.1). The indication for osteotomy was a degenerative disease in 29 cases, instability associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in 15 cases and a previous fracture around the knee with consecutive osteoarthritis in 10 cases.

Primary outcome was defined as survival of the osteotomy without conversion to total knee arthroplasty. Osteotomy survival after 5 years was 98% (CI, 95–100%), 92% (CI 86–99%) after 10 years and 71% (CI 58–85%) after 15 years. Figure 2a shows the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. One patient received the total knee arthroplasty within 2 years, three between 6 and 9 years and the others (nine) between 10 and 15 years after osteotomy. Comparison between open and closing wedge HTO showed no significant difference in survival (P = 0.76; Log-rank test; Fig. 2b). Indication for TKR was in all cases progressive pain in association with progression of osteoarthritis on the radiograph. The case revised after a year had an initial undercorrection of the osteotomy with persisting varus alignment and therefore no pain relief. The three cases revised between 6 and 9 years were borderline indications, one with associated chondrocalcinosis and two with associated instability of the anterior cruciate ligament.

The median Visual Analogue Scale (0–10) at follow-up was 0 (IQR 1–0; range 0–5). The median Satisfaction Index (0–100%) at follow-up was 80% (IQR 63–89; range 30–100). On clinical examination, the median range of motion was 130° (IQR 116–139; range 85–145) flexion and 0° (IQR 0–6; range 0–10) extension. Effusion was absent in 69% (20) of patients and slight in 31% (9). No marked instability was recorded, including for the remaining patients with initial associated instability. The median BMI at follow-up was 25 (IQR 21–29.5; range 19.5–36.7).

KOOS and WOMAC scores are presented in Fig. 3. The median KOOS score was 71 (IQR 49–82, range 9–100) and the median WOMAC score 84 (IQR 66–96; range 9–100). Comparison between patients with open and closing wedge osteotomy in terms of KOOS and WOMAC showed no significant difference (P = n.s.).

On the activity scale, 29% of osteotomy survivors were at level 2, 52% at level 3 and 19% at level 4. None of the survivors were at level 0, 1 or 5 (Table 1).

Radiological evaluation showed slight progression of the degree of osteoarthritis following the Kellgren and Lawrence classification [16] from osteotomy until follow-up from grade 2 (IQR 1–2.25; range 1–3.5) to 3 (IQR 2–3; range 1–3) in the medial compartment and grade 0 (IQR 0–0.75; range 0–1) to 1.25 (IQR 1–2; range 0–4) in the lateral compartment. In each case, the axis before surgery passed through the diseased compartment, whereas in the follow-up control the axis passed in each case through the healthy compartment or at least through the centre of the knee (Fig. 4). The median correction was 10° (IQR 9.25–13.5; range 7–18) from an anatomical femorotibial angle of 178° (IQR 175–181; range 171–184) preoperatively to 190° (IQR 188–190; range 184–190) postoperatively. The mean loss of correction till follow-up was −2° (IQR −2 to 0; range −3 to 1).

Discussion

The most important finding of the study is the high survival rate of HTO after 5 (98%), 10 (92%) and 15 (71%) years. This is slightly superior to other reports from Western countries [5, 8, 12, 23, 26, 29, 34]. Only two Japanese and one French reports show higher osteotomy survival after 15 years (90–93%) [3, 9, 18]. This demonstrates that osteotomies around the knee can have a similar survival as joint arthroplasties.

We present one of the longer follow-up periods after valgisation osteotomies of the knee for unicompartmental degenerative diseases. Similar long-term follow-up studies have also been done by other authors [3, 5, 8, 18, 23, 26, 29, 37]. However, 24% of our patients were unavailable for follow-up: six died, six moved abroad and six were lost to follow-up. This may compromise evaluation but is often unavoidable in a long-term follow-up of up to 21 years. In the present study, this was associated with low levels of pain as indicated in the Visual Analogue Scale, a high Satisfaction Index and good scores in the KOOS and WOMAC evaluations. These data also showed that osteotomy survivors, despite having a mean age of 61 years, had a high level of activity. Patients showed good average joint mobility, no marked instability and none or minor effusion. In radiological evaluations, the mechanical axis passed through the opposite (lateral) compartment for all patients and the loss of correction was minimal. To achieve the exact planned correction during operation may be one of the key factors for good long-term results. Only a moderate increase of osteoarthritis was observed in the radiographic evaluation. Given that an additional knee arthroscopy was not performed on a regular basis, an evaluation of the preoperative condition of the cartilage and its role as a possible predictor for clinical outcome is not possible. To determine the severity of preoperative osteoarthritis, the classification of Kellgren and Lawrence was used [16].

Looking at patients converted to TKA, most operations were performed more than 10 years after HTO. Generally, osteoarthritis progressed and increasing symptoms led to indication for surgery. As full-leg radiographs are only done occasionally and not all files were available, a profound analysis is not possible. We therefore could not draw predictable reasons for failure out of this data.

We investigated the differences between open and closing wedge HTO and found similar results with respect to survival and functional outcome of the survivors. However, these results must be approached with caution as the case number of patients with open wedge HTO was small. Literature comparing clinical outcome after open versus closing wedge HTO is very limited and long-term comparisons are completely lacking [13].

Our results not only confirm the long-term effectiveness of valgisation high tibial osteotomy as treatment for medial compartment osteoarthritis, but there is also evidence that the open wedge technique can have a similar long-lasting effect as the traditional closing wedge high tibial osteotomy. This has a high clinical relevance as nowadays an increasing percentage of HTO are done using the open wedge technique, and long-term experiences are very limited.

After the ‘success story’ of total knee arthroplasty in the 1980s and 1990s, a revival of osteotomies around the knee is occurring. The osteotomy technique has significantly improved since patients in the present study underwent surgery [1, 15, 19, 30, 31]. New plates with angular stability allow open wedge osteotomies without bone grafting [30]. A more aggressive rehabilitation programme with a reduced risk of secondary dislocation is possible. Arthroplasties have shown their limitations with respect to inexplicable persisting pain, unsatisfactory flexion, chronic synovitis (polyethylene debris) and infections with multiresistant germs [20, 28, 33]. From our viewpoint, osteotomies around the knee are an ideal surgical treatment of unicompartmental degenerative diseases with associated varus for active patients. Activity demands are more crucial than the chronological age of the patient, so the age of 65 years should not be considered to be the upper limit. Unicompartmental arthroplasties are, in the case of maintained ligamentous stability and minor varus alignment, a potential alternative. Total knee arthroplasties should be reserved for unicompartmental or bicompartmental diseases in older and/or lower-demanding patients.

The success of osteotomies depends primarily on correct indication. Patients should have good pain tolerance because a low pain threshold is often a negative factor in the outcome of the treatment of musculoskeletal disease. Precise planning as stressed by Fujisawa (who showed the importance of correct positioning of the mechanical axis) as well as appropriate surgical technique achieving the desired correction are fundamental [10, 11, 21].

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, it is a retrospective study with the innate shortcomings of such a design. Despite scrupulous efforts, data collection is not complete. Up to 21 years after surgery not all patients’ files were entirely available and patient history was often clipped, making a coherent list of complications impossible. Furthermore, the different subgroups such as patients with an additional instability are too small to permit evident conclusions.

Conclusion

In summary, we found open as well as closing wedge high tibial osteotomies to be a successful and long-lasting method of treatment for unicompartmental degenerative diseases with associated varus in active patients. Survival of both techniques is comparable in our series and is associated with low pain scores, high satisfaction and high activity levels of the survivors.

References

Agneskirchner JD, Freiling D, Hurschler C, Lobenhoffer P (2006) Primary stability of four different implants for opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:291–300

Akamatsu Y, Koshino T, Saito T, Wada J (1997) Changes in osteosclerosis of the osteoarthritic knee after high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 334:207–214

Akizuki S, Shibakawa A, Takizawa T, Yamazaki I, Horiuchi H (2008) The long-term outcome of high tibial osteotomy: a ten- to 20-year follow up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 90:592–596

Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW (1988) Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 15:1833–1840

Billings A, Scott DF, Camargo MP, Hofmann AA (2000) High tibial osteotomy with a calibrated osteotomy guide, rigid internal fixation, and early motion. Long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 82:70–79

Bonnin M, Chambat P (2004) Current status of valgus angle, tibial head closing wedge osteotomy in media gonarthrosis. Orthopade 33:135–142

Coventry MB (1973) Osteotomy about the knee for degenerative and rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 55:23–48

Coventry MB, Ilstrup DM, Wallrichs SL (1993) Proximal tibial osteotomy. A critical long-term study of eighty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 75:196–201

Flecher X, Parratte S, Aubaniac JM, Argenson JN (2006) A 12–28-year followup study of closing wedge high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 452:91–96

Fujisawa Y, Masuhara K, Shiomi S (1979) The effect of high tibial osteotomy on osteoarthritis of the knee. An arthroscopic study of 54 knee joints. Orthop Clin North Am 10:585–608

Gautier E, Jakob RP (1996) The value of corrective osteotomies–indications, technique, results. Ther Umsch 53:790–796

Gstottner M, Pedross F, Liebensteiner M, Bach C (2008) Long-term outcome after high tibial osteotomy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 128:111–115

Hoell S, Suttmoeller J, Stoll V, Fuchs S, Gosheger G (2005) The high tibial osteotomy, open versus closed wedge, a comparison of methods in 108 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 125:638–643

Huskisson EC (1982) Measurement of pain. J Rheumatol 9:768–769

Jacobi M, Jakob RP (2005) Open wedge osteotomy in the treatment of medial osteoarthritis of the knee. Tech Knee Surg 4:70–78

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS (1957) Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 16:494–502

Koshino T, Tsuchiya K (1979) The effect of high tibial osteotomy on osteoarthritis of the knee. Clinical and histological observations. Int Orthop 3:37–45

Koshino T, Yoshida T, Ara Y, Saito I, Saito T (2004) Fifteen to twenty-eight years’ follow-up results of high tibial valgus osteotomy for osteoarthritic knee. Knee 11:439–444

Lobenhoffer P, Agneskirchner JD (2003) Improvements in surgical technique of valgus high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 11:132–138

Mandalia V, Eyres K, Schranz P, Toms AD (2008) Evaluation of patients with a painful total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 90:265–271

Marti CB, Gautier E, Wachtl SW, Jakob RP (2004) Accuracy of frontal and sagittal plane correction in open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Arthroscopy 20:366–372

Miniaci A, Ballmer FT, Ballmer PM, Jakob RP (1989) Proximal tibial osteotomy. A new fixation device. Clin Orthop Relat Res 246:250–259

Naudie D, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Bourne TJ (1999) The install award. Survivorship of the high tibial valgus osteotomy. A 10- to -22-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 367:18–27

Odenbring S, Egund N, Lindstrand A, Lohmander LS, Willen H (1992) Cartilage regeneration after proximal tibial osteotomy for medial gonarthrosis. An arthroscopic, roentgenographic, and histologic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 277:210–216

Outerbridge RE (1961) The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br 43-B:752–757

Rinonapoli E, Mancini GB, Corvaglia A, Musiello S (1998) Tibial osteotomy for varus gonarthrosis. A 10- to 21-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 353:185–193

Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD (1998) Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 28:88–96

Seyler TM, Marker DR, Bhave A et al (2007) Functional problems and arthrofibrosis following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89(Suppl 3):59–69

Sprenger TR, Doerzbacher JF (2003) Tibial osteotomy for the treatment of varus gonarthrosis. Survival and failure analysis to twenty-two years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A:469–474

Staubli AE, Simoni CD, Babst R, Lobenhoffer P (2003) TomoFix: a new LCP-concept for open wedge osteotomy of the medial proximal tibia—early results in 92 cases. Injury 34(Suppl 2):55–62

Stoffel K, Stachowiak G, Kuster M (2004) Open wedge high tibial osteotomy: biomechanical investigation of the modified Arthrex osteotomy plate (Puddu plate) and the TomoFix plate. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 19:944–950

Takahashi S, Tomihisa K, Saito T (2002) Decrease of osteosclerosis in subchondral bone of medial compartmental osteoarthritic knee seven to nineteen years after high tibial valgus osteotomy. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 61:58–62

Toms AD, Davidson D, Masri BA, Duncan CP (2006) The management of peri-prosthetic infection in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 88:149–155

van Raaij T, Reijman M, Brouwer RW, Jakma TS, Verhaar JN (2008) Survival of closing-wedge high tibial osteotomy: good outcome in men with low-grade osteoarthritis after 10–16 years. Acta Orthop 79:230–234

Wakabayashi S, Akizuki S, Takizawa T, Yasukawa Y (2002) A comparison of the healing potential of fibrillated cartilage versus eburnated bone in osteoarthritic knees after high tibial osteotomy: an arthroscopic study with 1-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 18:272–278

Weber BG, Brunner CF (1982) Special techniques in internal fixation. Springer, New York

Yasuda K, Majima T, Tsuchida T, Kaneda K (1992) A ten- to 15-year follow-up observation of high tibial osteotomy in medial compartment osteoarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 282:186–195

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schallberger, A., Jacobi, M., Wahl, P. et al. High tibial valgus osteotomy in unicompartmental medial osteoarthritis of the knee: a retrospective follow-up study over 13–21 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19, 122–127 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1256-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1256-4