Abstract

The purpose of this multicenter retrospective study was to analyze the causes for failure of ACL reconstruction and the influence of meniscectomies after revision. This study was conducted over a 12-year period, from 1994 to 2005 with ten French orthopaedic centers participating. Assessment included the objective International Knee Documenting Committee (IKDC) 2000 scoring system evaluation. Two hundred and ninety-three patients were available for statistics. Untreated laxity, femoral and tibial tunnel malposition, impingement, failure of fixation were assessed, new traumatism and infection were recorded. Meniscus surgery was evaluated before, during or after primary ACL reconstruction, and then during or after revision ACL surgery. The main cause for failure of ACL reconstruction was femoral tunnel malposition in 36% of the cases. Forty-four percent of the patients with an anterior femoral tunnel as a cause for failure of the primary surgery were IKDC A after revision versus 24% if the cause of failure was not the femoral tunnel (P = 0.05). A 70% meniscectomy rate was found in revision ACL reconstruction. Comparison between patients with a total meniscectomy (n = 56) and patients with preserved menisci (n = 65) revealed a better functional result and knee stability in the non-meniscectomized group (P = 0.04). This study shows that the anterior femoral tunnel malposition is the main cause for failure in ACL reconstruction. This reason for failure should be considered as a predictive factor of good result of revision ACL reconstruction. Total meniscectomy jeopardizes functional result and knee stability at follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Among medical reports on revision anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, no series was found reporting the incidence and influence of meniscectomies. Furthermore, the causes for failure of ACL reconstruction are analyzed in short series [7, 12, 41]. In these series, technical errors are considered to be the most frequent causes for failure of ACL reconstruction but no author emphasizes the consequences of these errors on the results of further revision. For these reasons, on the basis of a large series of revision ACL reconstruction conducted by the French Arthroscopic Society [8], this study specifically focused on causes for failure and on the role of the meniscal status. The hypothesis was that medial meniscectomy has a negative influence on the final results of revision ACL reconstruction.

Materials and methods

This retrospective multicenter study was conducted over a 12 year period, from 1994 to 2005 with ten French orthopaedic centers participating. Inclusion criteria were failure of a primary autogenous ACL reconstruction, intact posterior cruciate ligament, non-operated contralateral knee and revision ACL reconstruction performed with an autogenous graft. ACL reconstruction is commonly considered a failure for one of the two following reasons: loss of knee motion due to the development of progressive arthrofibrosis or loss of stability secondary to recurrent patholaxity [19]. In this study, only the primary ACL reconstructions that lead to the recurrence of knee instability and to revision ACL reconstruction were considered as a failure. Failures of synthetic grafts were excluded to render the patient group as homogenous as possible. The minimum follow-up required was 1 year. To be included in the study, patients had to be evaluated with the subjective and objective International Knee Documenting Committee (IKDC) 2000 scoring system [25] at follow-up. The subjective IKDC 2000 form is based on a 100-point score. The objective IKDC 2000 form includes ligament, mobility and radiographic assessment. Radiographic assessment included 30° flexion monopodal weight-bearing AP and lateral radiographs of both knees and comparative 45° flexion AP views (“Schuss” view). Ligament assessment was performed clinically by the pivot shift test, whereas for anterior laxity, clinical and instrumental measurements (TELOS or KT 1000) were performed. Data for each patient was collected in a database edited on File Maker Pro 6. Data was collected on both the primary and the revision ACL reconstruction, the post-operative rehabilitation, the complications and reoperations, the subjective and objective IKDC 2000 scores after the revision ACL reconstruction and the radiographic status before and after the revision surgery. Furthermore, two parameters were carefully assessed: the causes for failure and the meniscal status. The following mechanisms of failure were searched for: untreated laxity, femoral tunnel malposition, tibial tunnel malposition, radiological impingement between the ACL graft and the intercondylar roof, failure of fixation, new trauma and infection. Femoral tunnel malposition was evaluated following previously published criteria [1] as well as tibial tunnel positioning [21]. Impingement between the intercondylar roof and the graft was analyzed following Howell’s recommendations [21, 23]. Based on these, tunnel positioning was analyzed on AP and lateral radiographs. Failure of graft fixation was considered as such only when it occurred in the early post-operative period, before graft incorporation. It occurred at one of the fixation sites and depended on both the type of fixations and the type of grafts [31, 32, 43]. Considering the menisci, data was collected at each stage of the knee story. Meniscal surgery was observed before, during or after primary ACL reconstruction, and then during or after revision ACL surgery. Two hundred and ninety-three patients were available for statistics [8]. There were 203 men and 173 right knees. The median age at time of surgery was 23 years (13 to 57), the interval between primary and revision surgery was 5 years (2 months to 15 years) and the median age at revision was 28 (14 to 63). The median follow-up was 30 months (12 to 160). The primary ACL reconstruction was a bone-patellar tendon-bone (BTB) graft in 200 cases (68%), a semi-tendinosus and gracilis (STG) graft in 87 (30%) and a quadricipital tendon (QT) graft in 6.

Statistical analysis: After inclusion and complete review of the data, data files were centralized for correction and statistical analysis. In a univariate analysis, the statistical tests used were the Chi-square test and the Student t test, when required. Statistics were performed using Statview 5.0 (Symantec Inc.). The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

The causes for failure of primary ACL reconstruction leading to revision are summarized in Table 1. Technical problems (anterior femoral tunnel, malposition of tibial tunnel, failure of fixation) represent 50% of the failures. Anterior positioning of the femoral tunnel was found in 36% of failures (108 cases out of 293). The second most frequent reason for failure was a true new trauma, which was observed in 30% of the failures. In this series, “supposed” traumatisms were not considered as responsible for failure, because in this etiology, another reason was always found to explain the failure. Tibial tunnel malposition was three times less frequent than femoral tunnel malposition and occurred in 11% of the patients (32 out of 293). This tunnel was positioned either too far anteriorly or posteriorly. Radiological impingement between the primary ACL graft and the intercondylar notch was found in the same percentage of cases. Failure of the fixation system, untreated peripheral laxity and hyperlaxity represented around 5% of the failures. Finally, no reason for failure was found in 15% of the patients (44 cases out of 293). It was observed that only the malpositon of the femoral tunnel was predictive of a better functional result of revision surgery. Indeed, at final follow-up, 44% were IKDC A after revision in the group of patients with an anterior femoral tunnel as a cause for failure of the primary surgery, versus 24% if the cause of failure was not the femoral tunnel. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

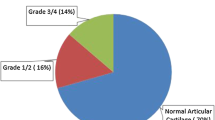

The cumulative incidence of medial and lateral meniscectomies was 70%. The evolution of the meniscal status during the knee story is summarized in Fig. 1. Meniscectomies were performed before or during primary surgery in 23% of the patients. The rate of meniscectomies increased to 33% between the primary and the revision ACL reconstruction because of isolated meniscectomies performed during this period. The rate of meniscectomies was raised to 67% when adding those performed during the revision ACL reconstruction and finally, the inclusion of meniscectomies following revision ACL reconstruction further increased this rate to 70%. The meniscal status is of significant influence on the objective IKDC score and on knee stability, as summarized in Table 2. At final follow-up, patients with conserved menisci had a better functional result and a better knee stability than those with a total meniscectomy (P = 0.04).

Discussion

The most important finding of the present study is that failures of ACL reconstruction are due to technical errors in 50% of the cases. This rate is in accordance with previous well-documented studies on causes for failure in revision ACL reconstruction [7, 10, 28]. Among technical errors, the femoral tunnel malposition is the most common cause of failure reported in all studies of revision ACL reconstruction [4, 7, 9, 11–14, 16, 17, 29, 30, 35–37, 39, 41, 44–47]. In particular, the femoral tunnel placement is exceedingly anterior in most of the cases because of difficulties of visualization of the “over the top” position on the femur during endoscopic ACL procedures [15, 27]. Despite the fact that this technical problem has been previously described and is well known as the “resident ridge pitfall”, it remains the main source of ACL reconstruction failure. The anterior malposition of the femoral tunnel leads first, to a loss of flexion because the graft is overtensioned already at 90° of flexion [6, 18] and secondly, to the recurrence of instability when the too short intraarticular graft fails during rehabilitation, or when the patient goes back to sport.

This study also shows for the first time that if the failure of the primary ACL graft is due to an anterior femoral tunnel malposition, the final result of the revision ACL reconstruction will be statistically superior to revision for another cause. Therefore, we believe that an anterior femoral tunnel malposition should be considered as a predictive factor of good result of revision ACL reconstruction. Another cause or technical reason for ACL graft failure is tibial tunnel malposition, but this surgical mistake is less frequent. In this study, femoral malposition is thrice more common than tibial malposition, and this rate is in accordance with other series [7, 12, 41]. If the tibial tunnel is too anterior, it leads to a loss of extension and impingement with the intercondylar notch [1, 20, 22, 40]. If the tibial tunnel is too posterior, it leads to an incomplete control of laxity because the intraarticular graft is too vertical. It should be kept in mind that the anteriorization of the femoral tunnel is not corrected by the posteriorization of the tibial tunnel [26]: impingement between the ACL graft and the intercondylar notch is always avoided if the graft is well-positioned on the femur and on the tibia.

Another finding of this study is that true traumatic reinjury of a well-positioned and well-fixed graft is nearly as frequent as the femoral tunnel problem. The found 30% rate is in accordance with the most recent studies [7, 12, 41] and is 2 to 3 times higher than those of the case series reported in the 90’s [15, 27, 28, 35, 46]. Two main reasons could explain this observation : first, the high demand of the patients, who currently expect to go back to their previous type of sports at the same level after ACL reconstruction and second, over-aggressive rehabilitation, which can run contrary to the ACL graft integration [38] and therefore to the ligamentization process [3]. Nowadays, accelerated rehabilitation, as described by Shelbourne [42], is validated for primary [5, 24], but is questionable for revision ACL reconstruction. This is demonstrated by two recent retrospective studies reporting the results of semi-tendinosus and gracilis grafts : while Ferretti [12] recommended partial weight-bearing for 3 weeks and an extension brace for 6, Salmon and Pinczewski [41] used no brace, immediate full weight-bearing and range of motion, and observed the same failure rate.

Finally, this study demonstrates for the first time that the meniscus is of significant influence on the functional result and on knee stability in knees reconstructed by revision ACL, as summarized in Table 2. Patients who sustained a total meniscectomy, at any point of the knee story, i.e. before, during or after the primary or the revision reconstruction, revealed a significantly lower IKDC score and a significantly lower pivot shift control than the patients with conserved menisci. This assessment is in accordance with the findings of McConville [33] and confirms that the meniscus is not only a cartilage keeper [2, 34] but also a knee stabilizer. Therefore, we believe that conservation of the menisci is of major importance in knee reconstruction. This goal is not yet reached, as demonstrated by the 70% rate of meniscectomies in this series, in accordance with almost all the series published on revision ACL reconstruction.

Despite these significant results on the influence of the meniscus, one must keep in mind the limits of the current study, due to its design: being a retrospective, multicenter and non-randomized study, it may include possible bias. The clinical relevance of this study is to avoid technical errors, especially anterior femoral tunnel malposition when performing ACL reconstruction and to avoid total meniscectomy at all cost.

Conclusion

This study shows that anterior femoral tunnel malposition is the main cause for failure in ACL reconstruction and that this reason for failure should be considered as a predictive factor of good result of revision ACL reconstruction. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that total meniscectomy jeopardizes the functional result and knee stability.

References

Aglietti P, Buzzi R, D’Andria S, Zaccherotti G (1992) Arthroscopic anterior cruciate reconstruction with patellar tendon. Arthroscopy 8:510–516

Aglietti P, Zacherotti G, De Biase P (1994) A comparison between medial meniscus repair, partial meniscectomy, and normal meniscus in ACL reconstructed knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 307:165–173

Amiel D, Kleiner JB, Roux RD, Harwood FL, Akeson WH (1986) The phenomenon of “ligamentization” anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon. J Orthop Res 4:162–172

Bach B (2003) Revision anterior cruciate ligament ligament surgery. Arthroscopy 19:14–29

Boileau P, Rémi M, Lemaire M, Rousseau P, Desnuelle C, Argenson C (1999) Plaidoyer pour une rééducation accélérée après ligamentoplastie du genou par un transplant os-tendon rotulien-os. Rev Chir Orthop 85:475–490

Bylski-Austrow DI, Grood ES, Hefzy MS, Holden JP, Butler DL (1993) Anterior cruciate ligament replacements: a mechanical study of femoral attachment location, flexion angle at tensioning and initial tension. J Orthop Res 8:522–531

Carson W, Anisko EM, Restrepo C, Panariello RA, O’Brien SJ, Warren RF (2004) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Etiology of failures and clinical results. J Knee Surg 17:127–132

Colombet PH, Neyret PH, Trojani C, Sbihi A, Djian P, Potel JF, Hulet C, Jouve F, Bussière C, Ehkirch P, Burdin G, Dubrana F, Beaufils P, Franceschi JP, Chassaing V (2007) Revision ACL surgery. Rev Chir Orthop 93(suppl 8):5S54–5S67

Colosimo AJ, Heidt RS, Traub JA, Calonas RL (2001) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with a reharvested ipsilateral patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med 29:746–750

Cross M, Purnell R (1994) Revision reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Orthopaedic Trans 17:931

Eberhardt C, Kurth AH, Hailer N, Jäger A (2000) Revision ACL reconstruction using autogenous patellar tendon graft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8:290–295

Feretti A, Conteduca F, Monaco E, De Carli A, D’arrigo C (2006) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with doubled semitendinosus and gracilis tendons and lateral extra-articular reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:2373–2379

Fox J, Pierce M, Bojchuk J, Hayden J, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr (2004) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with nonirradiated fresh-frozen patellar tendon allograft. Arthroscopy 20:787–794

Fules PJ, Madhav RT, Goddard RK, Mowbray MA (2003) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autografts with a polyester fixation device. Knee 10:335–340

Greis PE, Johnson DL, Fu FH (1993) Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery: causes of graft failures andtechnical considerations of revision surgery. Clin Sports Med 12:839–852

Grossman MG, ElAttrache NS, Shields CL, Glousman RE (2005) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: three to nine year follow-up. Arthroscopy 21:418–423

Harilainen A, Sandelin J (2001) Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery: a review of the literature and resultst of our own revisions. Scand J Med Sci Sports 11:163–169

Harner CD, Irrgang JJ, Paul J, Dearwater S, Fu FH (1992) Loss of motion after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 283:187–195

Harter RA, Osternig LR, Singer KM, James SL, Larson RL, Jones DC (1988) Long term evaluation of knee stability and function following surgical reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. Am J Sports Med 16:434–443

Howell SM, Clark JA, Farley TE (1991) A rationale for predicting anterior cruciate graft impingement by the intercondylar roof. A magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med 19:276–281

Howell SM, Clark JA (1992) Tibial tunnel placement in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions and graft impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 283:187–195

Howell SM, Taylor MA (1993) Failure of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament due to impingement by the intercondylar roof. J Bone Joint Surg Am 75:1044–1055

Howell SM, Barad SJ (1995) Knee extension an its relationship to the slope of the intercondylar roof. Implications for positioning the tibial tunnel in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Am J Sports Med 23:288–294

Howell SM, Taylor MA (1996) Brace-free rehabilitation, with early return to activity, for knees reconstructed with a double-looped semitendinosus and gracilis gaft. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78:814–825

Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, Harner CD, Neyret P, Richmond JC, Shelbourne KD, International Knee Documentation Committee (2006) Responsiveness of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med 34:1567–1573

Jackson DW, Gasser SI (1994) Tibial tunnel placement in ACL reconstruction. Arthroscopy 10:124–131

Jaureguito J, Paulos L (1996) Why grafts fail. Clin Orthop Relat Res 325:25–41

Johnson D, Cohen M (1995) Revision ACL surgery: etiology, indications, techniques and results. Am J Knee Surg 8:155–176

Johnson DL, Swenson TM, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD (1996) Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament surgery: experience from Pittsburgh. Clin Orthop Relat Res 325:100–109

Kartus J, Stener S, Lindahl S, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J (1998) Ipsi or contra-lateral patellar tendon graft in anterior cruciate ligament revision surgery: a comparison of two methods. Am J Sports Med 26:499–504

Kousa P, Järvinen TL, Vihavainen M, Kannus P, Järvinen M (2003) The fixation strength of six hamstring tendon graft fixation devices in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part II: tibial site. Am J Sports Med 31:182–188

Kousa P, Järvinen TL, Vihavainen M, Kannus P, Järvinen M (2003) The fixation strength of six hamstring tendon graft fixation devices in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part I: femoral site. Am J Sports Med 31:174–181

Mc Conville OR, Kipnis JM, Richmond JC et al (1993) The effect of meniscal status on knee stability and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 9:431–439

Neyret P, Donnel ST, Dejour D (1993) Partial meniscectomy and ACL rupture in soccer players. A study with a minimum 20 years follow-up. Am J Sports Med 21:455–460

Noyes F, Barber-Westin SD (1996) Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament surgery: experience from Cincinati. Clin Orthop Relat Res 325:116–129

Noyes F, Barber-Westin SD (2001) Revision ACL surgery with the use of bone patellar tendon bone autogenous grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83:1131–1143

O’Neil D (2004) Revision arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament with previously unharvested ipsilateral autografts. Am J Sports Med 32:1833–1841

Pinczewski LA, Clingefeller AJ, Otto DD et al (1997) Integration of hamstring tendon with bone in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy 13:641–643

Rollier JC, Besse JL, Lerat JL, Moyen B (2007) Anterior cruciate ligament revision: analysis and results from a series of 74 cases. Rev Chir Orthop 93:344–350

Romano VM, Graf BK, Keene JS, Lange RH (1993) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The effect of tibial tunnel placement on range of motion. Am J Sports Med 21:415–418

Salmon LJ, Pinczewski LA, Russell VJ, Refshauge K (2006) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon autograft. 5- to 9- year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 34:1604–1614

Shelbourne KD, Nitz P (1990) Accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 18:292–299

Steiner ME, Hecker AT, Brown CH Jr, Hayes WC (1994) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Comparison of hamstrings ans patellar tendon grafts. Am J Sports Med 22:242–246

Taggart T, Kumar A, Bickerstaff D (2004) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a midterm patient assessment. Knee 11:29–36

Texier A, Hulet C, Acquitter Y (2001) Reconstruction itérative du ligament croisé antérieur sous arthroscopie. A propos de 32 cas. Rev Chir Orthop 87:653–660

Uribe JW, Hetchtman Zvijac JE (1996) Revision ACL surgery: experience from Miami. Clin Orthop Relat Res 325:91–99

Woods GW, Fincher AL, O’Connor DP, Bacon SA (2001) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the lateral third of the ipsilateral patellar tendon after failure of the central-third graft: a preliminary report on 10 patients. Am J Knee Surg 14:23–31

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trojani, C., Sbihi, A., Djian, P. et al. Causes for failure of ACL reconstruction and influence of meniscectomies after revision. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19, 196–201 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1201-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1201-6