Abstract

This report presents an athletic patient with swelling and progressive pain on the posteromedial side of his right ankle on weight bearing. MRI demonstrated tenosynovitis and suspicion of a length rupture. On posterior tibial tendoscopy, there was no rupture, but medial from the tendon a tissue cord came into view, causing impingement on the tendon at the level of maximum pain. The cord was released and 2 weeks and 1 year after the procedure the patient reported no complaints.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A patient suffering from pathology to the posterior tibial tendon (PTT) can present with posteromedial ankle pain solely. On physical exam, an inability to walk tip-toes, pain on palpation of the PTT and a positive PPT provocation test further point in the direction of PTT pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US) can be used to differentiate between the different pathologies: tenosynovitis, (longitudinal) ruptures and degeneration can be diagnosed [4, 5, 7, 10, 11]. Posterior tibial tendoscopy has proved to be a valuable technique for removal of inflamed synovium, pathological vinculae, adhesions and irregularities of sliding channels [1–3, 9, 13, 14] in and around the PTT. Several studies have been published in which tendoscopy for these pathologies is performed, with the advantages of decreased postoperative pain, less morbidity, outpatient treatment and no postoperative immobilisation [2, 3, 13]. Small abnormalities can be assessed because of the enlargement of an endoscopic image and consequently treated. When on tibialis posterior tendoscopy a tear is located, it can be sutured through a mini-open approach offering the advantages of endoscopic resection of tenosynovitis and a small incision at the level of the rupture [2]. This case report describes a PTT tendoscopy for an MRI suspected longitudinal rupture. A longitudinal rupture was not encountered but a tissue cord causing impingement on the PTT.

Case report

A 35-year-old patient complained about pain and swelling on the posteromedial side of his right ankle on weight bearing. The complaints were progressive over the last 6 months. The patient had increased intensity and length of his long distance runs, but now complaints were withholding him from doing sports. A sudden snap was never felt. Conservative measures were undertaken with modest effect. On physical examination, we found mild varus leg axes with neutral hindfoot position. Performing a single heel rise was ponderous but possible. Swelling was visible at the navicular insertion of the posterior tibial tendon with pain on palpation from the insertion on the navicular bone proximally, to the posterior aspect of the medial malleolus. The PPT provocation test was painful. Conventional radiography showed no abnormalities. MRI demonstrated effusion around the posterior tibial tendon indicating tenosynovitis, with high intratendinous signal intensity on proton density (PD) and T2-weighted images suspicious for a length rupture; however, this diagnosis could not be disclosed with certainty.

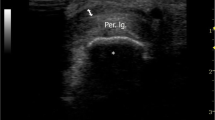

It was decided to perform a posterior tibial tendoscopy for removal of the tenosynovitis and to identify a potential longitudinal rupture, that if present could be debrided and sutured through a mini-open approach. Before anaesthesia, the patient was asked to actively invert the foot, so that the posterior tibial tendon could be palpated, and the portals as well as the level of maximum pain were marked. The distal portal was made first, 2.5 cm distal to the posterior edge of the medial malleolus. A 2.7-mm 30° arthroscope was introduced, and the complete tendon sheath was inspected by rotating the arthroscope around the tendon (Fig. 1).

A rupture could not be identified, but medial from the tendon a tissue cord came into view, causing impingement on the tendon at the level of maximum pain (Fig. 2).

Under direct vision, the proximal portal was made using a spinal needle, after which an incision was made into the tendon sheath and a 2.7-mm shaver was introduced. The cord was released (Fig. 3). The portals were sutured, and a pressure bandage for 2–3 days was applied. The patient was instructed to perform active range of motion exercises directly postoperative, to partially bear weight for 2–3 days, and gradually resume daily activities. Two weeks after the procedure, the patient reported no complaints and had already been on a 4-h bike ride. The ankle was slender, showed a normal range of motion and no instability. At one-year follow-up, he was still complaint free and able to perform 10-km runs.

Discussion

This report describes a case in which a partial tendon tear was suspected on MRI but was not found on posterior tibial tendoscopy. Instead, we found a cord-like adhesion causing friction at the location of the pathology corresponding with the level of maximum pain.

Only one case series on open surgery reported exact findings, 5 patients had non-specific tenosynovitis, and one showed ‘adhesions’ [8]. In open surgery, it is likely that these small ‘cords’ are not noticed. Three series have been published on posterior tibial tendoscopy [2, 3, 13]. Only in the first series in 1997, the exact preoperative findings were described [13]. Sixteen procedures were performed, mostly for tenosynovitis, but in 4 a pathological vincula and in 3 adhesions were found and removed [13].

Another advantage of starting with the endoscopic procedure in this case was that the MRI suspected partial tendon rupture could be ruled out, so that opening the skin and tendon sheath from the musculotendinous junction to the navicular insertion as is performed in open surgery was not necessary. This way there is reduced risk of infection and postoperative pain, fewer adhesions caused by scar tissue are formed, and rehabilitation is quicker.

In conclusion, we recommend posterior tibial tendoscopy not only for patients without a (partial) tendon tear, but also for patients with a suspected or radiologically diagnosed partial tendon tear. When tears remain undisclosed on tendoscopy, it can prevent the patient from a large incision, increased postoperative pain and prolonged rehabilitation. When partial tears are found, the procedure can be converted to a mini-open approach, which is still less invasive than the standard open procedure.

References

Bare AA, Haddad SL (2001) Tenosynovitis of the posterior tibial tendon. Foot Ankle Clin 6:37–66

Bulstra GH, Olsthoorn PG, van Dijk CN (2006) Tendoscopy of the posterior tibial tendon. Foot Ankle Clin 11:421–427

Chow HT, Chan KB, Lui TH (2005) Tendoscopic debridement for stage I posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 13:695–698

Conti S, Michelson J, Jahss M (1992) Clinical significance of magnetic resonance imaging in preoperative planning for reconstruction of posterior tibial tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle 13:208–214

Conti SF (1994) Posterior tibial tendon problems in athletes. Orthop Clin North Am 25:109–121

Khoury NJ, el-Khoury GY, Saltzman CL, Brandser EA (1996) MR imaging of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 167:675–682

Kong A, Van DV (2008) Imaging of tibialis posterior dysfunction. Br J Radiol 81:826–836

Langenskiold A (1967) Chronic non-specific tenosynovitis of the tibialis posterior tendon. Acta Orthop Scand 38:301–305

Paus AC (1996) Arthroscopic synovectomy. When, which diseases and which joints. Z Rheumatol 55:394–400

Rosenberg ZS (1994) Chronic rupture of the posterior tibial tendon. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2:79–87

Rosenberg ZS, Cheung Y, Jahss MH, Noto AM, Norman A, Leeds NE (1988) Rupture of posterior tibial tendon: CT and MR imaging with surgical correlation. Radiology 169:229–235

Trnka HJ (2004) Dysfunction of the tendon of tibialis posterior. J Bone Joint Surg Br 86:939–946

van Dijk CN, Kort N, Scholten PE (1997) Tendoscopy of the posterior tibial tendon. Arthroscopy 13:692–698

van Dijk CN, Scholten PE, Kort N (1997) Tendoscopy (tendon sheath endoscopy) for overuse tendon injuries. Oper Techn Sports Med 5:170–178

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Sterkenburg, M.N., Haverkamp, D., van Dijk, C.N. et al. A posterior tibial tendon skipping rope. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18, 1664–1666 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1194-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1194-1