Abstract

ACL reconstruction with bone patellar tendon bone (BPTB) grafts has been shown to produce dependable results. Recently, reconstructions with double-looped semitendinosus gracilis (DLSG) grafts have become common. The prevailing opinion is that ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon graft produces a more stable knee with more anterior knee pain than DLSG grafts, while the functional results and knee scores are similar. The present study evaluates BPTB grafts fixed with metallic interference screws and DLSG grafts fixed with Bone Mulch Screw on the femur and WasherLoc fixation on the tibia. All else being the same, there is no difference in the outcome between the two grafts and fixation methods. This is a prospective randomized multicenter study. A total of 115 patients with isolated ACL ruptures were randomized to either reconstruction with BPTB grafts fixed with metal interference screws (58 patients) or DLSG grafts (57 patients) fixed with Bone Mulch Screws and WasherLoc Screws. Follow-up was at one and two years; the latter by an independent observer. At two years, one ACL revision had been performed in each group. Eight patients in the DLSG group and one in the BPTB group underwent meniscus surgery in the follow-up period (P = 0.014). Mean Lysholm score at the two year follow-up was 91 (SD ± 10.3) in the DLSG group and also 91 (SD ± 10.2) in the BPTB group. Mean KT-1000 at two years was 1.5 mm in the BPTB group and 1.8 mm in the DLSG group (n.s.). At two years, four patients in the BPTB group and three in the DLSG group had a Lachman test grade 2 or 3 (n.s.). More patients in the BPTB group had pain at the lower pole of the patella (P = 0.04). Peak flexion torque and total flexion work were lower in the DLSG group at one year (P = 0.003 and P = 0.000) and total flexion work also at two years (P = 0.05). BPTB ACL reconstruction fixed with interference screws and DLSG fixed with Bone Mulch Screws on the femur and WasherLoc Screws on the tibia produce satisfactory and nearly identical outcomes. Among our patients in the DLSG group, flexion strength was lower, and more patients underwent meniscus surgery in the follow-up period. The BPTB group has more anterior knee pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) may lead to instability, pain, swelling, mechanical dysfunction and an increased risk of meniscal injury and degenerative changes [5, 12, 20, 29, 30, 44, 47]. Rupture of the ACL is a frequent injury in athletes of all ages. Female athletes are more frequently injured than male athletes [4], although the total number of ACL injuries in males far out number those in females [26].

Non-operative treatment may lead to suboptimal knee function and to joint deterioration [9, 10, 29, 47]. For this reason, many procedures have been developed to restore stability and allow patients to have a more active life. Since the late 1980s, reconstruction of the ACL with the central third of the patellar tendon with proximal and distal bone blocks has been shown to produce dependable results [12, 13, 55, 56]. The fixation of these grafts is most commonly performed with metal- or bioabsorbable interference screws. This procedure is well documented with good results [7, 12, 14]. The development of new fixation methods and endoscopic techniques has decreased the morbidity of ACL reconstruction without compromising the results [19, 37, 57]. However, graft site problems and anterior knee pain continue to be of concern [33, 38]. For this reason, use of the hamstring tendons as a graft source has become increasingly popular [39, 60]. The many fixation methods are well documented [6, 32, 51]. Lawhorn and Howell [36] described the hamstring technique of Bone Mulch Screw® (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) on the femur and WasherLoc® (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) fixation on the tibia, as used in the current study. Less donor site morbidity has been reported using the hamstring tendons [6, 43]. Both surgical procedures result in knees with good stability [3, 6, 28, 40, 43].

This study compared the clinical results of these two surgical procedures on isolated ACL injuries. The fixation methods used in this study have never been compared before. The hypothesis is that there is no difference in clinical outcome after ACL reconstructions with BPTB grafts fixed with metallic interference screws, or DLSG grafts fixed with Bone Mulch Screw on the femur and WasherLoc fixation on the tibia.

Materials and methods

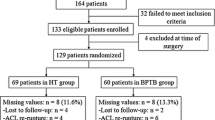

One hundred and fifteen patients, 73 men and 42 women with isolated ACL ruptures, at four hospitals, were, between 2001 and 2004, prospectively randomized preoperatively, by drawing a sealed envelope. Either a BPTB graft fixed with metal interference screws (Linvatec, Largo, FL) (58 patients) or a DLSG graft fixed with the Bone Mulch Screw and the WasherLoc (Biomet, Inc. Warsaw, IN) (57 patients) was used. The patients received written and oral information about the study and signed a written consent form.

Patients between 18 and 45 years with isolated ACL ruptures and normal two plane radiographs were included in the study. Patients with major additional injury of the knee, previous major surgical procedures in the knee, cartilage injuries grade three or four, patients in need of meniscal repairs, patients with malalignment more than 5 degrees varus or valgus and patients with treated or untreated ACL injuries in the other knee were excluded.

Follow-up examinations were done at one and two years. The two-year follow-up was done by the same, blinded independent observer (experienced physiotherapist) at all four hospitals. The scars were covered, so that the examiner did not know which type of surgery had been done. At the follow-ups, the Tegner activity score[58], Lysholm functional score[58], assessment of the subjective knee function, KT-1000 maximum manual force, Cybex 6000 isokinetic dynamometer, range of motion, patellofemoral crepitation, effusion, Lachman test, pivot shift test and clinical examinations were performed. Additionally, at the two-year follow-up, the knee walking test, the triple jump test and the Stairs hopple test were performed [52].

The surgical technique with the BPTB graft was a standard endoscopic procedure as described in a previous study [14]. If necessary, a notch plasty was done. The graft was harvested from the middle third of the ipsilateral ligamentum patellae. A tibial guide was used that is designed to place the guide pin 4–5 mm posterior and parallel to the slope of the intercondylar roof with the knee in full extension in both groups. The femoral aimer was inserted through the tibial tunnel and hooked in the over-the-roof position at 10 o’clock for the right knee and 2 o’clock for the left knee in both groups. In the BPTB group, the femoral bone block was fixed from the inside with a cannulated interference screw of 7 mm × 25 mm. The knee was cycled several times, and the grafts were tensioned with approximately 4 kg in both groups. The bone block in the tibial tunnel was fixed with an interference screw of 9 mm × 25 mm with the knee in full extension.

The surgical technique with the DLSG graft was followed as described by Lawhorn and Howell [36]. The semitendinosus and gracilis tendons were harvested using a tendon stripper. The graft was sized using sizing sleeves. The diameter of the smallest sizing sleeve that freely passes over the graft without friction was used to select a drill for reaming the tibial and femoral tunnels. Bone reamings were collected to compact into the femoral and tibial tunnel. The tunnel for the Bone Mulch Screw was drilled using an 8-mm cannulated reamer. With the help of a loop around the tip of the Bone Mulch Screw, the tendons were pulled through the tunnels. A mallet was used to impact the WasherLoc until it had fully compressed the tendons against the posterior wall of the tibia tunnel. The fixation was secured with a cancellous screw in the tibia. With the compaction rod inserted in the bore of the Bone Mulch Screw, bone mulch was compacted into the femur.

The patients in both groups underwent an aggressive rehabilitation program [27, 54]. Immediately after the operation, the patients started knee movement, and full passive extension of the knee was carried out several times a day. No brace was used. Full weight bearing was allowed as soon as tolerated. Closed-chain exercises with full extension and flexion of the knee were allowed as early as possible in both groups. Jogging began after 10–12 weeks. After 6 months, the patients were allowed to return to any sporting activity, provided that the strength of the thigh muscle on the operated side was at least 85% of that on the contra lateral side, and that controlled functional training has been carried out without difficulty.

Functional tests

After warming up, the patients performed the triple jump test with three jumps, starting on both feet, landing and jumping twice on the normal leg and landing on both feet. The same was done for the treated leg. The test was carried out twice on both legs. The greatest distance for each leg was selected, and the difference between the two legs calculated [52]. The patient marked the amount of pain during the test on the operated leg with a VAS ranging from “No pain” to “Unbearable pain”.

The stairs hopple test was performed starting on the non-operated leg. The patient jumped 22 steps up and 22 steps down on the same leg [52]. The time in seconds was recorded. The same procedure was performed on the operated leg. If in need of balance support, the test was performed near a hand rail. The patient marked the amount of pain during the test on the operated leg on a VAS scale [46].

The knee walking test was performed on a soft examination bench with the patient walking in place on the knees [34]. The test person marked one of the four alternatives: “No pain”, “Light pain”, “Severe pain” and “Unbearable pain” for each knee.

Muscle strength measurements of the quadriceps femoris and hamstring muscles consisted of 5 repetitions at an angular velocity of 60°/s followed by a 1-minute rest period and 30 repetitions at 240°/s. The concentric force was tested. The parameters used for analysis were total work and peak torque.

The study was approved by The Regional Ethics Committee of middle Norway at the Norwegian university of science and technology.

Statistical methods

Sample size was estimated on the basis of the hypothesis that there was no difference in anterior–posterior knee laxity between the treatment groups. A clinically relevant difference between the groups was considered to be a 1-mm increase in anterior knee laxity compared to the contra lateral side. The standard deviation, as has been shown in a previous trial, was 1.5 mm [14]. A power calculation was performed with a confidence level of 95% (α = 0.05) and a power (1−ß) of 90%. This yielded an estimated sample size of 48 patients per group, and, when combined with an expected rate of patients lost to follow-up of 20% at two years, a sample size of 58 patients per group, or a total of 115 patients, was required. A comparison of the differences between the groups was made with the Student’s t test for continuous variables and with the chi-square test and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. In all tests, an alpha level of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

At the time of surgery, the median age was 27 years (18–50) in the DLSG-group and 26 years (18–49) in the BPTB group. Median time from injury to surgery was 12 months (0–240) in the DLSG group and 13 months (2–180) in the BPTB group (n.s.). The mean preoperative KT-1000 difference between injured and uninjured knee was 5.8 mm (±2.3 range 2–13) in the DLSG group and 6.1 mm (±2.4 range 1–13) in the BPTB group (n.s.).

At the two-year follow-up, one ACL revision had been performed in each group, and both were excluded from the follow-up. Sixteen patients were lost to follow-up. Eight had moved to a foreign country, and eight were unwilling to attend or unavailable. A total of 97 patients (84%) were examined by the independent examiner; 47 patients in the DLSG group and 50 patients in the BPTB group (Fig. 1). Ten patients in the DLSG group and five in the BPTB group underwent additional knee surgery in the follow-up period (n.s.). Eight of the patients in the DLSG group and one in the BPTB group underwent meniscus surgery (P = 0.014) (Table 1).

Mean Lysholm score at the two-year follow-up was 91(±10.3 range 12–100) in the DLSG group and also 91 (±10.2 range 30–100) in the BPTB group and are shown in Fig. 2. The Tegner scores are shown in Fig. 3. There were no significant differences between the groups at any follow-up.

Preoperatively, none of the patients rated their knee function as excellent, and only 11 of the 97 patients rated their knee function as good. At the two-year follow-up, 32 out of 87 patients (37%) felt their knee function was excellent, and 45 out of 87 patients (52%) rated their function good (n.s.) (Fig. 4).

Compared to the normal contra lateral knee, four patients in the DLSG group and five in the BPTB group had an extension deficit of 5° or more at one year and also at two years. Two patients in the DLSG group and three in the BPTB group had a flexion deficit of 10° or more at one year, and respectively three and one at two years (n.s.).

There was no significant differences between the groups on mean KT-1000 at any follow-up (Fig. 5).

At the one-year follow-up, no patients in the BPTB group and one patient in the DLSG group had a Lachman test grade ≥2 (n.s.). The numbers at two years were four and three patients respectively (n.s.).

Four patients in the DLSG group and five in the BPTB group had a positive pivot glide at two years (n.s.).

The mean difference between the injured and uninjured leg at the triple jump test was 0 (±28 range −58 to 93) cm in the DLSG group and −5 (±36 range −130 to 75) cm in the BPTB group (n.s.).

The mean difference between the injured and uninjured leg at the Stairs hopple test was 2 (±12 range −14 to 43) sec. in the DLSG group and 1 (±28 range −15 to 44) s in the BPTB group (n.s.).

No patients in the DLSG group and two in the BPTB group had severe pain at the knee walking test at two years, and this test was impossible to perform for two patients in the BPTB group (n.s.) (Fig. 6). Twelve patients in the BPTB group and four in the DLSG group had pain on palpation of the lower pole of the patella at two years (P = 0.04).

The strength measurements are shown in Fig. 7a, b. At the one-year follow-up, the total hamstring work values in the DLSG group, compared to the uninjured knee, showed a mean reduction of 82 (±97 range −402 to 45)N/m, and an increase of 18 (±90 range −379 to 191)N/m in the BPTB group (P = 0.00). At the two-year follow-up, there was a mean reduction of 62 (±68 range −230 to 104)N/m in the DLSG group, and of 20 (±91 range −167 to 238)N/m in the BPTB group (P = 0.05). The total hamstring work in the DLSG group was reduced by 17% at one-year and 12% at the two-year follow-up.

The mean peak hamstring torque, compared to the uninjured knee, was reduced by 10 (±11 range −38 to 13) N/m in the DLSG group and increased by 2 (±16 range −29 to 37) N/m in the BPTB group at one year (P = 0.003). The values at the two-year follow-up were a decrease of 7 (±11 range −33 to 19) N/m and 2 (±14 range −31 to 38) N/m respectively (P = 0.089). There was no difference between the groups when testing quadriceps strength.

Discussion

The most important findings of the present study were the Cybex tests which showed lower total flexion work values in the DLSG group at one and two years and lower peak flexion torque in the DLSG group at one year. Similar results have been published by other authors [6, 8]. Some, however, [3, 17] found no differences between the groups. The rehabilitation program in the present study was aggressive and same in both groups. This rehabilitation might have been too aggressive for the hamstring patients during the first months after surgery. At the moment, a less aggressive rehabilitation program for the hamstring patients is considered. The present study showed no signs of quadriceps weakness in any group after two years. Corry [11] found that thigh atrophy was significantly less in the hamstring tendon group at 1 year after surgery, a difference that had disappeared by 2 years. There was no difference between the injured and uninjured leg performing the triple jump test and the Stairs hopple test, suggesting a weak correlation between these functional tests and the muscle strength tests. In Aune`s study [6], comparing BPTB grafts and DLSG grafts, no differences were found between the groups on the stairs hopple test results. The single-legged hop test result was better for the DLSG group after 6 and 12 months, but no differences was found after 24 months. In Beynnon`s study [8], the two treatments produced similar outcomes in terms of ability to perform a single-legged hop, bear weight, squat, climb stairs, run in place, and duck walk.

In the present study, like in other similar studies [15, 22], isokinetic muscle torque was tested. A low correlation between these tests and functional performance tests has been found [48] as in this study. However, the ability to produce high force quickly in sports and in injury protection is important. Therefore, authors have suggested being more sport-specific not only for force but also velocity [35]. Neeter et al. [45] concluded that a test battery consisting of a knee extension, knee flexion and leg press muscle power test had a high ability to determine deficits in leg muscle power 6 months after ACL injury and reconstruction.

Meta-analyses of studies comparing BPTB to DLSG grafts have shown that ACL reconstruction with BPTB probably results in a more stable knee but is accompanied by more anterior knee pain, while quadrupled hamstring grafts have similar subjective and functional results but produce less anterior knee pain, less patellofemoral crepitation and is less likely to cause extension loss [18, 21, 23, 25, 50]. However, there are no randomized studies in the literature comparing BPTB ACL reconstruction fixed with interference screws [12] and DLSG fixed with Bone Mulch Screws on the femur and WasherLoc Screws on the tibia [36]. The purpose of this paper is to test the hypothesis that ACL reconstruction done with these two surgical procedures produces satisfactory and identical outcomes.

In the present study, one ACL revision had been performed in each group at the two-year follow-up. The revision rate was 2% in both groups. In Freedman’s study [23], the rate of graft failure in the patellar tendon group was statistically significantly lower (1.9 vs. 4.9%) than in the hamstring tendon group. Sajovic et al. [53] found that graft rupture occurred in 7% of the hamstring tendon group and in 8% of the patellar tendon group at the 5-year follow-up. In Wagner’s study [59], 5.6% had a graft rupture in the hamstring tendon group and 4.2% in the BPTB group (n.s.).

In this study, there was no difference between the groups concerning the Tegner activity score, the Lysholm functional score or the patients’ evaluation of subjective knee function. Several clinical studies show similar results [2, 6, 8, 11, 41, 42, 53].

Anterior knee pain is a significant problem in cultures where kneeling is important. In the present study, in the BPTB group, the patients had more pain on the inferior pole of the patella, and some patients had severe problems performing the knee walking test. Other studies have similar findings [1, 6, 11, 23, 59]. Therefore, harvesting of the BPTB graft should be avoided in patients where kneeling is important.

The present study showed no significant differences in KT1000 measurements, Lachman test or pivot shift at two years. Only four patients in the DLSG group and five in the BPTB group had a positive pivot glide at two years, and none had instability of a higher grade. Several studies show that both surgical procedures result in knees with good stability [3, 6, 11, 16, 24, 49]. However, some authors found more stable knees after BPTB reconstructions [2, 8, 23]. Järvelä et al. [31] found that rotational stability of the knee was better when using the double-bundle technique instead of the single-bundle technique in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The single-bundle technique used in this study showed very few patients with a positive pivot glide, and none with a positive pivot shift in either group. From these results there is no reason to change to a double-bundle technique. However, quantification of the pivot shift test is known to be difficult.

In the present study, a significantly higher number of patients in the DLSG group underwent meniscus surgery within two years. Others have found no differences between the groups [3]. The differences in this study may be explained by the relatively large reduction in hamstring strength in the DLSG group.

The weaknesses of this study are the relatively low follow-up percentage (84%) and the relatively high number of surgeons participating in this multicenter study.

The clinical relevance of this study is that the use of these grafts and fixation methods produces equal clinical results; however, there is a concern about the loss of hamstring strength in the DLSG group, and therefore a less aggressive rehabilitation should be considered in this group.

Conclusion

BPTB ACL reconstruction fixed with interference screws and DLSG fixed with Bone Mulch Screws on the femur and WasherLoc Screws on the tibia produces satisfactory and nearly identical outcomes. At the two-year follow-up, the BPTB group had more anterior knee pain. However, in the hamstring group, flexion strength was lower, and more patients in the DLSG group underwent meniscus surgery in the follow-up period.

References

Aglietti P, Giron F, Buzzi R, Biddau F, Sasso F (2004) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: bone-patellar tendon-bone compared with double semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts. A prospective randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86:2143–2155

Aglietti P (1994) A comparison between medial meniscus repair, partial meniscectomy, and normal meniscus in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res 307:165–173

Aglietti P (1994) Patellar tendon versus doubled semitendinosus and gracilis tendons for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 22:211–217

Anderson AF, Dome DC, Gautam S, Awh MH, Rennirt GW (2001) Correlation of anthropometric measurements, strength, anterior cruciate ligament size, and intercondylar notch characteristics to sex differences in anterior cruciate ligament tear rates. Am J Sports Med 29:58–66

Arnold JA, Coker TP, Heaton LM, Park JP, Harris WD (1979) Natural history of anterior cruciate tears. Am J Sports Med 7:305–313

Aune AK, Holm I, Risberg MA, Jensen HK, Steen H (2001) Four-strand hamstring tendon autograft compared with patellar tendon-bone autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A randomized study with two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 29:722–728

Barber FA (2000) Bioscrew fixation of patellar tendon autografts. Biomaterials 21:2623–2629

Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Fleming BC, Kannus P, Kaplan M, Samani J, Renstrom P (2002) Anterior cruciate ligament replacement: comparison of bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts with two-strand hamstring grafts. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84:1503–1513

Bray RC, Dandy DJ (1989) Meniscal lesions and chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Meniscal tears occurring before and after reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Br 71:128–130

Buss DD, Min R, Skyhar M, Galinat B, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL (1995) Nonoperative treatment of acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries in a selected group of patients. Am J Sports Med 23:160–165

Corry IS (1999) Arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. A comparison of patellar tendon autograft and four-strand hamstring tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med 27:444–454

Drogset JO, Grontvedt T (2002) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with and without a ligament augmentation device : results at 8-Year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 30:851–856

Drogset JO, Grontvedt T, Tegnander A (2005) Endoscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts fixed with bioabsorbable or metal interference screws: a prospective randomized study of the clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med 33:1160–1165

Drogset JO, Grontvedt T, Robak OR, Molster A, Viset AT, Engebretsen L (2006) A sixteen-year follow-up of three operative techniques for the treatment of acute ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:944–952

Eastlack ME, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L (1999) Laxity, instability, and functional outcome after ACL injury: copers versus noncopers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 31:210–215

Ejerhed L, Kartus J, Sernert N, Kohler K, Karlsson J (1999) Patellar tendon or semitendinosus tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A prospective randomized study with a two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 7:19–25

Ejerhed L, Kartus J, Kohler K, Sernert N, Brandsson S, Karlsson J (2003) Preconditioning patellar tendon autografts in arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 52:6–11

Eriksson K, Anderberg P, Hamberg P, Lofgren AC, Bredenberg M, Westman I, Wredmark T (2001) A comparison of quadruple semitendinosus and patellar tendon grafts in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br 83:348–354

Fauno P, Kaalund S (2005) Tunnel widening after hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is influenced by the type of graft fixation used: a prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy 21:1337–1341

Feagin JA Jr, Curl WW (1976) Isolated tear of the anterior cruciate ligament: 5-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 4:95–100

Feller JA, Webster K (2003) A randomized comparison of patellar tendon and hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 31:564–573

Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L (2000) A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8:76–82

Freedman KB, D’Amato MJ, Nedeff DD, Kaz A, Bach BR Jr (2003) Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a metaanalysis comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med 31:2–11

Gobbi A, Mahajan S, Zanazzo M, Tuy B (2003) Patellar tendon versus quadrupled bone-semitendinosus anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective clinical investigation in athletes. Arthroscopy 19:592–601

Goldblatt JP, Fitzsimmons SE, Balk E, Richmond JC (2005) Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: meta-analysis of patellar tendon versus hamstring tendon autograft. Arthroscopy 21:791–803

Granan L, Bahr R, Steindal K, Furnes O, Engebretsen L (2008) Development of a national cruciate ligament surgery registry: the norwegian national knee ligament registry. Am J Sports Med 36:308–315

Grontvedt T, Engebretsen L, Bredland T (1996) Arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts with and without augmentation. A prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 78:817–822

Harilainen A, Linko E, Sandelin J (2006) Randomized prospective study of ACL reconstruction with interference screw fixation in patellar tendon autografts versus femoral metal plate suspension and tibial post fixation in hamstring tendon autografts: 5-year clinical and radiological follow-up results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:517–528

Hawkins RJ, Misamore GW, Merritt TR (1986) Followup of the acute nonoperated isolated anterior cruciate ligament tear. Am J Sports Med 14:205–210

Jacobsen K (1977) Osteoarthrosis following insufficiency of the cruciate ligaments in man. A clinical study. Acta Orthop Scand 48:520–526

Jarvela T, Moisala AS, Sihvonen R, Jarvela S, Kannus P, Jarvinen M (2008) Double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring autografts and bioabsorbable interference screw fixation: prospective, randomized, clinical study with 2-year results. Am J Sports Med 36:290–297

John PG, Sean EF, Ethan B, John CR (2005) Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: meta-analysis of Patellar tendon versus Hamstring tendon autograft. Arthroscopy 21:791–803

Kartus J, Stener S, Lindahl S, Engstrom B, Eriksson B, Karlsson J (1997) Factors affecting donor-site morbidity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 5:222–228

Kartus J, Movin T, Karlsson J (2001) Donor-site morbidity and anterior knee problems after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autografts. Arthroscopy 17:971–980

Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, Dudley GA, Dooly C, Feigenbaum MS, Fleck SJ, Franklin B, Fry AC, Hoffman JR, Newton RU, Potteiger J, Stone MH, Ratamess NA, Triplett-McBride T (2002) American college of sports medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:364–380

Lawhorn KW, Howell SM (2003) Scientific justification and technique for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autogenous and allogeneic soft-tissue grafts. Orthop Clin North Am 34:19–30

Lee Y, Kim SK, Park JH, Park JW, Wang JH, Jung YB, Ahn JH (2007) Double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using two different suspensory femoral fixation: a technical note. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 15:1023–1027

Liden M, Ejerhed L, Sernert N, Laxdal G, Kartus J (2007) Patellar tendon or semitendinosus tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized study with a 7-Year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 35:740–748

Lind M, Menhert F, Pedersen AB (2009) The first results from the Danish ACL reconstruction registry: epidemiologic and 2 year follow-up results from 5, 818 knee ligament reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17:117–124

Maletis GB, Cameron SL, Tengan JJ, Burchette RJ (2007) A prospective randomized study of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison of patellar tendon and quadruple-strand semitendinosus/gracilis tendons fixed with bioabsorbable interference screws. Am J Sports Med 35:384–394

Marder RA, Raskind JR, Carroll M (1991) Prospective evaluation of arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Patellar tendon versus semitendinosus and gracilis tendons. Am J Sports Med 19:478–484

Marder RA, Raskind JR, Carroll M (1996) Prospective evaluation of arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Patellar tendon versus semitendinosus and gracilis tendons. Am J Sports Med 20:478–484

Matsumoto A, Yoshiya S, Muratsu H, Yagi M, Iwasaki Y, Kurosaka M, Kuroda R (2006) A comparison of bone-patellar tendon-bone and bone-hamstring tendon-bone autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 34:213–219

McDaniel WJ Jr, Dameron TB Jr (1983) The untreated anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 172:158–163

Neeter C, Gustavsson A, Thomee P, Augustsson J, Thomee R, Karlsson J (2006) Development of a strength test battery for evaluating leg muscle power after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:571–580

Noyes FR, Mooar PA, Matthews DS, Butler DL (1983) The symptomatic anterior cruciate-deficient knee. Part I: the long-term functional disability in athletically active individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am 65:154–162

Noyes F, Barber SD, Mangine RE (1991) Abnormal lower limb symmetry determined by function hop tests after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med 19:513–518

Ostenberg A, Roos E, Ekdahl C, Roos H (1998) Isokinetic knee extensor strength and functional performance in healthy female soccer players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 8:257–264

Pinczewski LA, Deehan DJ, Salmon LJ, Russell VJ, Clingeleffer A (2002) A five-year comparison of patellar tendon versus four-strand hamstring tendon autograft for arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med 30:523–536

Poolman RW, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M (2007) Hamstring tendon autograft better than bone patellar-tendon bone autograft in ACL reconstruction: a cumulative meta-analysis and clinically relevant sensitivity analysis applied to a previously published analysis. Acta Orthopaedica 78:350–354

Prodromos CC, Fu FH, Howell SM, Johnson DH, Lawhorn K (2008) Controversies in soft-tissue anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: grafts, bundles, tunnels, fixation, and harvest. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 16:376–384

Risberg MA, Ekeland A (1994) Assessment of functional tests after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 19:212–217

Sajovic M, Vengust V, Komadina R, Tavcar R, Skaza K (2006) A prospective, randomized comparison of semitendinosus and gracilis tendon versus patellar tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: five-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 34:1933–1940

Shelbourne KD, Gray T (1997) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft followed by accelerated rehabilitation. A two- to nine-year followup. Am J Sports Med 25:786–795

Shelbourne KD, Urch SE (2000) Primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the contralateral autogenous patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med 28:651–658

Shelbourne KD, Klootwyk TE, Wilckens JH, De Carlo MS (1995) Ligament stability two to six years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft and participation in accelerated rehabilitation program. Am J Sports Med 23:575–579

Steiner ME, Hecker AT, Brown CH Jr, Hayes WC (1994) Anterior cruciate ligament graft fixation. Comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts. Am J Sports Med 22:240–246

Tegner Y, Lysholm J (1985) Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop 198:43–49

Wagner M, Kaab MJ, Schallock J, Haas NP, Weiler A (2005) Hamstring tendon versus patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using biodegradable interference fit fixation: a prospective matched-group analysis. Am J Sports Med 33:1327–1336

Zantop T, Kubo S, Petersen W, Musahl V, Fu FH (2007) Current techniques in anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 23:938–947

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Lars Engebretsen for the assistance with the manuscript and Physiotherapist Øystein Skare for the independent observations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drogset, J.O., Strand, T., Uppheim, G. et al. Autologous patellar tendon and quadrupled hamstring grafts in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized multicenter review of different fixation methods. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18, 1085–1093 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-009-0996-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-009-0996-5