Abstract

Treatment with painful eccentric muscle training has been demonstrated to give good clinical results in patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis. The pain mechanisms in chronic painful shoulder impingement syndrome have not been scientifically clarified, but the histological changes found in the supraspinatus tendon have similarities with the findings in Achilles tendinosis. In this pilot study, nine patients (five females and four males, mean age 54 years) with a long duration of shoulder pain (mean 41 months), diagnosed as having shoulder impingement syndrome and on the waiting list for surgical treatment (mean 13 months), were included. Patients with arthrosis in the acromio-clavicular joint or with large calcifications causing mechanical impingement during horizontal shoulder abduction were not included. We prospectively studied the effects of a specially designed painful eccentric training programme for the supraspintus and deltoideus muscles (3×15 reps, 2 times/day, 7 days/week, for 12 weeks). The patients evaluated the amount of shoulder pain during horizontal shoulder activity on a visual analogue scale (VAS), and satisfaction with treatment. Constant score was assessed. After 12 weeks of treatment, five patients were satisfied with treatment, their mean VAS had decreased (62–18, P<0.05), and their mean Constant score had increased (65–80, P<0.05). At 52-week follow-up, the same five patients were still satisfied (had withdrawn from the waiting list for surgery), and their mean VAS and Constant score were 31 and 81, respectively. Among the satisfied patients, two had a partial suprasinatus tendon rupture, and three had a Type 3 shaped acromion. In conclusion, the material in this study is small and the follow-up is short, but it seems that although there is a long duration of pain, together with bone and tendon abnormalities, painful eccentric supraspinatus and deltoideus training might be effective. The findings motivate further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The chronic painful shoulder is well known to be difficult to treat [10]. Subacromial impingement syndrome is commonly associated with a painful condition in the shoulder, not seldom involving chronic pain-symptoms [8, 16, 26]. Neer defined subacromial impingement as a painful contact between the rotator cuff, subacromial bursa, and the undersurface of the anterior acromion [25]. He defined three stages (I–III) of the condition. Stage III is charaterized by mechanical disruption (partial or full thickness) of the rotator cuff tendon, and changes in the coracoacromial arch (like osteophytes along the anterior acromion) [26]. In the chronic stage, surgical treatment (acromioplasty) is often employed, but the long-term clinical results are not always encouraging [17].There are many theories about the pain in this condition, but it has still not been scientifically clarified where the pain comes from in this condition [7, 9, 12, 31]. Is it from the subacromial bursa, the rotatorcuff tendons, the acromion, or is it from a combination of pathology in these different tissues? [13, 15, 19, 31].

There is a common opinion that painful shoulder exercises should be avoided in the treatment of painful impingement syndrome in the shoulder [3, 6, 23, 24]. However, there is no scientific background to these opinions, and appropriate studies are missing. Histological examinations of the rotatorcuff (supraspinatus tendon) in patients with impingement syndrome have shown tendon changes described as tendinosis, similar to what have been found in chronic painful Achilles and patellar tendinosis [13, 19]. Interestingly, painful eccentric calf muscle training has been demonstrated to give good clinical results in patients with chronic painful mid-portion Achilles tendinosis [1].

The aim of this pilot study was to investigate if treatment with painful eccentric supraspinatus and deltoideus muscle training was effective in patients with a long duration of pain-symptoms related to subacromial impingement syndrome in the shoulder.

Material and methods

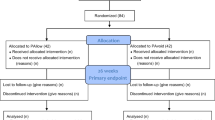

Nine patients (five males and four females, mean 54, range 35–72 years) with chronic painful impingement syndrome, where included in the study. All patients had a long duration of pain symptoms (mean 41 months, range 23–72), and were on the waiting list for surgical treatment (mean 13 months, range 4–30 months). All patients had tried different treatment regimens like rest, cortisone injections, NSAID, and different types of shoulder rehabilitation exercises. Basic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

The diagnosis was based on clinical examination, ultrasound and X-ray. The clinical examination included a positive Neers and Hawkins test. The Constant score was assesed, and Isobex isometric dynamometer (MDS Medical divice Solution A.G, Switzerland) was used to measure isometric muscle strength in 30° of horizontal abduction. The Isobex isometric dynamometer has been shown to have a good reliability for the measurment of shoulder muscle strength [14]. The same orthopaedic surgeon (P.W) performed all clinical examinations and tests.

Dynamic ultrasound examination was performed with a linear transducer (Acuson Sequoia 8L5, with 5–8 MHz frequency). The rotator cuff tendons and acromion were examined. The ultrasound examination was done to determine whether there were signs of substantial mechanical impingement between calcifications in the rotator cuff tendons and the acromion. An X-ray was performed to classify the shape of the acromion, to detect bone spurs and calcifications, and to determine whether there were signs of arthrosis in the acromio-clavicular joint. Patients with signs of arthrosis in the acromio-clavicular joint, or with large calcifications in the rotator cuff causing severe mechanical impingement during horizontal abduction, were not included in the study.

Eccentric training regimen

All patients were given practical and written instructions by the same physiotherapist (P.J) before the start of the study. A special eccentric muscle training model, mainly activating the supraspinatus and deltoideus muscles, was designed by the physiotherapist (P.J). A device called Ulla-sling, was attached to the roof or door and used to elevate the arm to a starting position (Fig. 1). The eccentric training programme was executed by having the patient to slowly lower the arm from the start position (30° of horizontal abduction with thumb pointing towards the ground Fig. 2a, b) and Fig. 3. This was done by 3×15 repetitions, twice a day, 7 days/week, for 12 weeks. When there was no pain during the excercise, the load was gradually increased by adding weights, to reach a new level of “painful” training (Fig. 4). Two weeks after the treatment, the patients were contacted by the physiotherapist (over telephone) to make sure that they did their exercises correctly. If there were any doubts about compliance or problems with performing the exercises, the patients were immediatly followed-up at the clinic. After 6 weeks, the patients were followed-up by the physiotherapist at the clinic, to answer questions, and to make sure that they were doing the exercises correctly. After 12 weeks of eccentric training, the patients were recommended to continue their exercises for at least 2 times/week.

A special devise called Ulla-sling was used to elevate the arm to the starting position (by pulling a string with the other arm)

The arm was kept at 30° of horizontal abduction with the tumb pointing downwards.The eccentric training programme was done by slowly lowering the arm from the start position. a Frontal view, b lateral view

Outcome measures

Constant score was used to assess shoulder function [9], before and after 12 weeks and 52 weeks of training. The patients estimated the amount of pain in the shoulder during horizontal shoulder activity on a 100-mm long visual analogue scale (VAS) before treatment, and 12 weeks and 52 weeks after treatment. The amount of pain was recorded from 0–100 mm, where no pain was recorded as 0 and severe pain as 100.

Patients satisfaction with treatment was assessed, (patients who said “no” indicated ’not satisfied’ and they remained on the wating list for surgery, and those who said “yes” indicated satisfied and they withdrew from the waiting list). Data are presented as mean and range values.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty at the University of Umeå. All patients gave their written consent to participate.

Statistics

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to compare the results from the Constant score and VAS evaluations, before and after 12 weeks and 52 weeks of treatment. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Specific data for each patient is presented in Table 2.

Before treatment, the mean Constant score was 51 (range 27–70), and the mean VAS was 71 (range 34–100).

After 12 weeks of eccentric training, five patients were satisfied with the treatment. Their mean Constant score was 80, and their mean VAS was 18. Mean Constant score and mean VAS for the ‘not satisfied’ patients were 50 and 67, respectively. For the ‘satisfied’ patients, there was a significant increase in the Constant score, (from 65–80 P<0.043), and a significant decrease in the VAS (from 62–18 P<0.043). At the 52-week follow-up, the five ’satisfied’ patients were still satisfied with the results of treatment. Their mean Constant score was 81, and their mean VAS was 31.

At the 12-week follow-up, the five patients satisfied with the result of treatment withdrew from the waiting list for surgical treatment.

One of the patients who was not satisfied after 12 weeks of treatment, had been wrongly diagnosed. This patient had a labrum tear that was detected at surgery.

Discussion

In this small pilot study, we tried painful eccentric supraspinatus and deltoideus training as a treatment model for patients with chronic shoulder pain, diagnosed as an impingement syndrome, and were on the waiting list for surgical treatment. The results were interesting, five out of nine patients, all very poor cases with a long duration of disabling pain symptoms, were satisfied with the result of treatment and withdrew from the waiting list for surgical treatment.

Actually, five of seven patients did well since one patient had a labral lesion and another one had a full-thickness cuff tear. This also shows that to get a correct diagnosis, most often, an arthroscopic evaluation is needed.

How can these results be explained? Since the number of patients is small it could be considered as a co-incidence that five out of seven patients were satisfied with the treatment. On the other hand, the treatment model was tested on a group of patients with a long duration of pain symptoms, and it is most likely that they were in a poor stage of the condition. In more painful conditions, it is well known that the longer the duration of symptom, the more difficult it is to treat the condition. Also, these patients were all on the waiting list for surgery, mentally prepared for surgical treatment, and therefore possibly less motivated to try a painful treatment regimen. Interestingly, although these five patients had been on the waiting list for surgery for a relatively long period of time, they decided to withdraw from the waiting list after only a 12-week follow-up. This possibly implies a dramatic change in their amount of shoulder pain, which is also indicated in their VAS evaluations.

An isometric muscle strength test was included in the Constant score evaluation, and when evaluating the results there were found to be no significant differences in isometric strength (performed in 30° of horizontal abduction) before and after treatment, in the five ’satisfied’ patients. Consequently, the favourable result of treatment is unlikely to be due to an increased muscle strength, especially not isometric strength. However, we cannot exclude that the dynamic strength was affected. What could then be the reason for the good results? Unfortunately, there are many questions which arise due to the pain associated with this condition. Where the pain comes from has still not been scientifically clarified. Biopsies taken from the rotator cuff (supraspinatus) have shown grossly similar tendon changes as for other chronic painful tendons, possibly indicating large similarities between these conditions [2, 13, 19, 22, 31]. Gotoh et al. [15] has suggested the subacromial bursa as a site for pain, showing high amounts of substance-P nerve fibers localised around vessels. Interestingly, recent scientific studies on chronic painful Achilles tendinosis have demonstrated vasculo-neural ingrowth as being the most likely source of pain in that condition [2], and that good clinical results after treatment with eccentric calf-muscle training were associated with the lack of remaining neovessels [32]. Also, Chansky and Iannoti [7] found neovascularisation to be associated with symptomatic rotator cuff disease secondary to mechanical impingement. Mechanical factors, such as the shape of the acromion, have been considered to be of significant importance [4, 25]. From our study, it is interesting to note that in three shoulders, which had a hook-shaped acromion (Bigliani grade 3), the treatment had a good result. In our study, the two patients with partial ruptures in the supraspinatus tendon had good results with the treatment, but in one patient with a total supraspinatus rupture only poor results were observed. This supports the theory that residual cuff muscles and prime movers might compensate for deficiencies in the torn supraspinatus tendon [12].

In this pilot study, we used painful eccentric training on patients with chronic shoulder pain. Previous studies have emphasized pain-free training during shoulder rehabilitation [5, 21, 23] to strengthen the depressor muscles like the subscapularis, infraspinatus and teres minor muscle [23, 24]. Studies have also recommended that patients should avoid a position with a long lever-arm, as the supraspinatus muscle activity has been demonstrated to be high when the arm is straight in the scapular plane. Other studies have recommended that instead of using the “empty can” (external rotation) position during supraspinatus training, “full can” (internal rotation) position should be used, because that position increases the subacromial space as the greater tuberosity clears from the undersurface of the acromion [6, 16, 18, 20, 21, 29, 30]. In our test position, we chose to perform the eccentric training in a shoulder position that decreased the subacromial space and placed maximum load on the supraspinatus and deltoideus muscle. When the patients could do the exercise without pain, we gradually increased the load on the supraspinatus and deltoideus muscle to reach a new level of painful training. Previous studies have shown good and promising results with painful eccentric training on other chronic painful tendon conditions [11, 27, 28].

In conclusion, in this small pilot study, a specially designed painful eccentric training model for the supraspinatus and deltoideus muscles showed promising short-term clinical results on a small group of patients with severe pain from impingement of the shoulder. The findings are interesting and motivate further studies, including long-term follow-up of large groups, randomised studies and the comparison of this treatment model with other treatment models.

References

Alfredson H, Pietilä T, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R (1998) Heavy-Load eccentric calf-muscle training for treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 26:360–366

Alfredson H, Öhberg L, Forsgren S (2003) Is vasculo-neural ingrowth the cause of pain in chronic Achilles tendinosis? An investigation using ultrasonography and colour Doppler, immunohistochemistry, and diagnostic injections. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 11:334–338

Bang M, Deyle G (2000) Comparison of supervised exercise with and without physical therapy for patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 30:126–137

Bigliani L, Morrison DS, April EW (1986) The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to the rotator cuff tears. Orthop Trans 10:228

Brewster C, Moynes Schwab D (1993) Rehabilitation of the shoulder following rotator cuff injury or surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 18:422–427

Burke W, Vangsness T, Powers C (2002) Strengthening the supraspinatus: a clinical and biomechanical review. Clin Orthop 402:292–298

Chansky HA, Iannotti JP (1991) The vascularity of rotator cuff. Clin Sports Med 10:807–822

Cohen R, William G (1998) Impingement syndrome and rotator cuff disease as repetitive motion disorder. Clin Orthop 351:95–100

Constant CR, Murley AH (1987) A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop 214:160–164

Desmeules F, Cote CH, Fremont P (2003) Therapeutic exercise and orthopedic manual therapy for impingement syndrome: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med 13:176–182

Fahlström M, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H (2003) Chronic tendon pain treated with eccentric calf-muscle training. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 11:327–333

Fukuda H, Hamada K, Nakajima T, Yamada N, Tomonaga A, Gotoh M (1996) Partial-thicness tears of the rotator cuff. A clinicopathological review based on 66 surgically verified cases. Int Orthop 20:257–265

Fukuda H (2003) The managment of partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br 85:3–11

Gerber C, Arneberg O (1992) Measurement of abductor strength with an electronical device (Isobex). J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2:S6

Gotoh M, Hamada K, Yamakawa H, Inoue A, Fukuda H (1998) Increased substance P in subacromial bursa and shoulder pain in rotator cuff disease. J Orthop Res 16:618–621

Hawkins RJ, Kennedy JC (1980) Impingement syndrome in athletes. Am J Sports Med 31:724–727

Hyvonen P, Lohi S, Jalovaara P (1998) Open acromioplasty does not prevent the progression of an impingement syndrome to a tear. J Bone Joint Surg Br 8:813–816

Itoi E, Kido T, Sano A, Urayama M, Sato K (1999) Which is more useful, the “full can test” or the “empty can test,” in detecting the torn supraspinatus tendon? Am J Sports Med 27:65–68

Kahn KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, Hardcourt P, Åström M (1999) Histopathology of common Tendinophaties. Sports Med 27:188–201

Kelly B, Kadrmas W, Speer K (1996) The manual examination for rotator cuff strength. Am J Sports Med 24:581–588

Litchfield R, Hawkins R, Dillman C, Atkins J, Hagerman G (1993) Rehabilitation for the overhead athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 18:433–441

Ljung BO, Alfredson H, Forsgren S (2004) Neurokinin 1-receptors and sensory neuropeptides in tendon insertions at the medial and lateral epicondyles of the humerus. Studies on tennis elbow and medial epicondylalgia. J Orthop Res 22:321–327

Morrison D, Frogameni A, Woodworth P (1997) Non-operativ treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg 79:732–737

Morrison DS, Greenbaum BS, Einborn A (2000) Shoulder impingement. Orthop Clin North Am 31:285–293

Neer CS (1972) Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg 54:41–50

Neer CS (1983) Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop 173:70–77

Purdam C, Jonsson P, Alfredson H, Lorentzon R, Cook J, Khan K (2003 A pilot study of the eccentric decline squat in the management of painful chronic patellar tendinopathy. BJSM (in press)

Svernlöv B, Adolfsson L (2001) Non-operative treatment regime including eccentric training for lateral humeral epicondyalgia. Scan J Med Sci Sports 11:328, 2013;206

Takeda Y, Kashiwaguchi S, Endo K, Matsuura T, Sasa T (2002) The most effective exercise for strengthening the supraspinatus muscle: evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med 30:374–381

Townsend H, Jobe F, Pink M, Perry J (1991) Electromyographic analysis of the glenohumeral muscles during a baseball rehabilitation program. Am J Sports Med 19:264–272

Yanagisawa K, Hamada K, Gotoh M, Tokunaga T, Oshika Y,Tomisawa M, Hwan Lee Y, Handa A, Kijima H, Yamazaki H, Nakamura M, Ueyama Y, Tamaoki N, Fukuda H (2001) Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the subacromial bursa is increased in patients with impingement syndrome. J Orthop Res 19:448–455

Öhberg L, Alfredson H (2003) Effect on neovascularisation behind the good results with eccentric training in chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc (in press)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jonsson, P., Wahlström, P., Öhberg, L. et al. Eccentric training in chronic painful impingement syndrome of the shoulder: results of a pilot study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14, 76–81 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-004-0611-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-004-0611-8