Abstract

Symptomatic calcifications of the rotator cuff tendons is well-known pathologic condition. However, pathologic calcifications may involve other structures of the locomotor system as well. We report about five patients (age 52–66 years) with a painful calcification at the proximal part of the medial collateral ligament of the knee joint. All five patients presented with load-dependent pain pretending meniscus symptoms, but manual valgus stress provoked severe pain at the medial side of the knee. Conventional X-ray examination showed a dense rounded deposit at the proximal part of the medial collateral ligament. Initially all patients were treated conservatively by needling and infiltration with a local anaesthetic. Open resection of the deposit was performed in four patients after unsuccessful conservative treatment. Postoperatively all patients were immediately free of pain. After a mean follow-up of 6 years (patient 1–4) (range=2.5–9.5 years), all patients were still free of pain. Histological evaluation of biopsies obtained during surgery showed nodular deposition of calcium at the collagen fibres, vascular proliferations and inflammative changes. Soft tissue calcifications have to be considered as a rare differential diagnosis in patients presenting with medial knee joint pain. Open resection reduces symptoms immediately. The histological changes seen were comparable to that reported about pathological tendon calcifications of the shoulder. Therefore, both conditions might be of the same aetiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Calcifying tendinopathy is characterized by large deposits of calcium between or on degenerated collagen fibrils. This pathological phenomenon was first described by Wolff in the semitendinous tendon [33]. However, the supraspinatus tendon is clearly the most commonly affected tendon [11]. In many cases, tendon calcification occurs as an asymptomatic incidental finding. Every fifth healthy person has a calcification of the rotator cuff [11, 20, 30]. The incidence of supraspinatus calcification increases with age and calcification is more usual in female than in male [20]. Symptomatic tendon calcifications can be the cause for severe shoulder pain.

In contrast to reports about pathologic tendon calcifications of the rotator cuff [10, 11, 20, 29, 30, 31], the literature provides much less information about pathological tendon or nonmuscular calcifications at other locations. For most other sites only case reports exist [1, 4, 5, 8, 19, 21, 23, 32].

Since symptomatic soft tissue calcifications are rare in other locations, they may mimic well-known symptoms of other disease states. This article presents clinical, radiological and histopathological findings of five patients with symptomatic calcification of medial collateral ligament of the knee joint.

Case reports

Five patients presented with acute pain at medial compartment of the knee joint in our outpatient clinic. The period of time between onset of pain and first medical advice varied from 2 days to 6 weeks. No acute prior injury was reported. Three patients were female, two were male. The age of patients was between 52 and 66 years (mean=59 years).

All patients had an area of local tenderness at the proximal insertion of the medial collateral ligament with no swelling. The meniscus signs were positive in all cases (Steinmann 1 and 2, Payr). Valgus stress was able to provoke painful symptoms. All knee joints were stable.

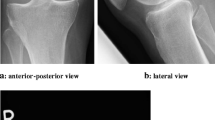

The conventional X-ray examination revealed a sharp dense calcific deposit (stage I according to Gärtner [6], size: approximately 0,5×1,5 mm) at the proximal insertion of the medial collateral ligament in all five cases (Fig. 1). Degenerative changes such as narrowing of the joint space, subchondral sclerosis of osteophytes could not be seen. At the initial visit, all patients were treated by infiltration with a local anaesthetic agent (Carbostesin 0.5%, Astra Zeneca, Hamburg, Germany). In one patient, this kind of treatment was curative. Since nonoperative treatment was unsatisfactory, the calcific deposit was excised in the other four patients. Open resection of the deposit was performed via a small interligamentous incision (Fig. 2) at the upper third part of the medial collateral ligament next to its femoral insertion in all cases. The consistency of the calcified material was like that of a creamy toothpaste. Postoperatively all patients were immediately free of pain (Fig. 3).

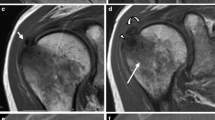

After a mean follow-up of 6 years (patient 1–4) (range=2.5–9.5 years), all patients were still free of pain. Histological evaluation of biopsies obtained during surgery showed nodular deposition of calcium in the collagen fibres, vascular proliferations and inflammative changes (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Calcifying tendinitis is a well-known disease of the rotator cuff tendons. But this pathological phenomenon has also been described in other tendons of different muscles as M. gluteus maximus, M. pectoralis major, M. rectus femoris, M. tibialis posterior, M. vastus lateralis, M. peroneaus longus and the flexors of the forefoot [1, 4, 5, 8, 19, 21, 23, 32]. Bursitis calcarea is known of phalangeal joints of the hand [17, 24, 34]. Kernohan et al. [12] mentioned a dolorous calcification of the lateral sesamoid bursa of the great toe. Iguchi et al. [7] described the clinical features of calcifying tendinitis in the medial head of the gastrocnemius in three elderly female patients.

We found no descriptions about single symptomatic calcifications of the medial collateral ligament of the knee joint in the literature. Since calcifying deposits in locations other than the shoulder are rare, misdiagnosis is common and this might lead to delay in treatment and recovery [9]. All patients of this study were in their fifties and sixties; therefore, the most common clinical differential diagnosis was osteoarthritis of the medial compartment or degenerative meniscus lesions. The radiological changes seen could mimic an old bony avulsion fracture of the medial epicondyle (Stieda-Pelligrini shadow). Another rare differential diagnosis was calcifications described in some autoimmune diseases, for example the Thibièrge-Weissenbach syndrome or the dermatomyositis [26]. None of the five patients had rheumatic disease.

The exact mechanism of calcium deposition in nonmuscular soft tissue is not clear. Most researches are done in calcifying tendinopathy. Codman [3] believed that calcium is deposited in necrotic and inflammatory tissue. However, Uthoff [29] described cases of supraspinatus calcification with no tendon degeneration or inflammatory tissue. These authors suggested that, due to persistent tissue hypoxia in a poorly vascularized tendon, a part of the tendon is transformed into fibrocartilage in which chondrocytes mediate the deposition of the calcium. This hypothesis is supported by anatomical studies which show that frequent locations of tendon calcifications are poorly vascularized [18, 25]. In the present study, the calcification was localized in the proximal part close to the chondral origin of the ligament. Chondral ligament attachments are characterized by a layer of fibrocartilage, which is interposed between the dense connective tissue of the ligament and the bone of the attachment site [13]. Various studies have shown that fibrocartilage is avascular [2, 27]. This coincidence of avascular tissue at tendon as well as ligament could be one reason for the calcifying of both tissues.

Chondrocyte-mediated calcification is a second pathological coincidence by fibrocartilage at tendon and ligament. Uhthoff and Sarkar [30] stated that calcifying tendinitis is a chondrocyte-mediated self-healing process. Chondrocyte-mediated calcification is a physiological process during endochondral ossification [28]. Other authors could not confirm the findings of Uhthoff in calcifications of other tendons [2, 4]. Jósza et al. [10, 28] found that in about half of the cases the calcification occurred without signs of fibrocartilaginous transformation.

One explanation for this discrepancy may be that calcifying tendinitis, as described by Uhthoff and Sarkar, in the rotator cuff [30] and calcifying tendinopathy in other locations are entirely different disease entities [10, 11]. A random coincidence of fibrocartilage and calcifications in the supraspinatus tendon might be an alternative explanation [16, 28].

Tendon calcification, as in other forms of tendon degeneration, is usually asymptomatic unless combined with inflammation [11]. All biopsies examined in the present study revealed signs of inflammative ligament tissue. This coincidence of anatomo-pathology and clinical signs for tendinous and ligamentous calcification is the third reason to postulate that the process of calcifying in both kinds of soft tissues should be the same.

The literature provides many treatment options for calcifying rotator cuff tendinopathy [11, 14]. Since the disease is frequently a self-healing process, a wait and see strategy accompanied by a nonsteroidal antiinflammative medication might be successful in cases with no severe symptoms [11, 14]. In more severe cases an invasive approach such as local infiltration or needling might be justified [11, 14]. Another treatment option for patients with chronic calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder is extracorporal shock wave application (ESWA) [14]. This method, however, is technically demanding and not always available. If these treatment options are unsuccessful, an arthroscopic excision of the calcifying deposit might be indicated [22]. This treatment strategy might also be applicable to other locations of calcifications than the rotator cuff. However, as in many other sites of the locomotor system in the medial collateral ligament an arthroscopic approach was not possible. In these cases open resection remains the treatment of choice [15].

References

Balogh B, Piza-Katzer H, Kosak D (1997) Bursitis calcarea—eine oft übersehene und fehldiagnostizierte Erkrankung der Hand. Z Orthop 135(6):539–554

Benjamin M, Quin S, Ralphs JR (1995) Fibrocartilage associated with human tendons and their pulleys. J Anat 187:625–633

Codman EA (1974) The shoulder. Thomas Todd, Boston, pp 193

Cox D, Paterson FWN (1991) Acute calcific tendinitis of peroneus longus. J Bone Joint Surg Br 73B:342

Delmi M, Kurt AM, Meyer JM, Hoffmeyer P (1995) Calcification of the tibialis posterior tendon: a case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Int 16 (12):792–795

Gärtner J, Heyer A (1993) Tendinosis calcarea der Schulter. Orthopade 24:284–302

Iguchi Y, Ihara N, Hijioka A, Uchida S, Nakamura T, Kikuta A, Nakashima T (2002) Calcifying tendonitis of the gastrocnemius. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 84(3):431–432

Ikegawa S (1996) Calcific tendinitis of the pectoralis major insertion—a case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 115:118–119

Johnson GS, Guly HR (1994) Acute calcific periarthritis outside the shoulder: a frequently misdiagnosed condition. J Accid Emerg Med 11:198–200

Józsa L, Balint BJ, Reffy A (1980) Calcifying tendinopathy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 97(4):305–307

Josza L, Kannus P (1998) Human tendons. Human Kinetics, London, pp 30–31

Kernohan J, Dakin PK, Helal B (1984) Dolorous calcification of the lateral sesamoid bursa of the great toe. Foot Ankle Int 5(1):45–46

Knese KH, Biermann H (1958) Die Knochenbildung an Sehnen und Bandansätzen im Bereich ursprünglich chondraler Apophysen. Z Zellforsch 49:142–187

Maier M, Stabler A, Lienemann A, Kohler S, Feitenhansl A, Durr HR, Pfahler M, Refior HJ (2000) Shockwave application in calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder-prediction of outcome by imaging. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 120(9):493–498

Maier M, Krauter T, Pellengahr C, Schulz CU, Trouillier H, Anetzberger H, Refior HJ (2002) Open surgical procedures in calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder—concomitant pathologies affect clinical outcome. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 140(6):656–661

Mohr W, Bilger S (1990) Morphologische Grundstrukturen der kalzifizierenden Tendopathie und ihre Bedeutung für die Pathogenese. Z Rheumatol 49:346–355

Piza-Katzer H, Weinstabl R (1987) Bursitis intermetacarpophalangea calcarea – Fallbericht. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir 19:95–97

Rathbun JB, McNab I (1970) The microvascular pattern of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br 52:539–545

Rehak DC, Fu FH (1999) Calcification of tendon of the vastus lateralis—a case report. Am J Sports Med 20(2):227–229

Reichelt A (1981) Beitrag zur operativen Therapie der Tendinosis calcarea der Schulter. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 119:21–24

Rhodes RA, Stelling CB (1986) Calcific tendinitis of the flexors of the forefoot. Ann Emerg Med 15(6):751–753

Rupp S, Seil R, Kohn D (2000) Tendinosis calcarea of the rotator cuff. Orthopade 29(10):852–867

Sarkar JS, Haddad FS, Crean SV, Brooks P (1996) Acute calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris. J Bone Joint Surg Br 78B:814–816

Schwarz M, Goth D (1989) Periarthritis calcarea der Fingergelenke. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir 21:328–330

Stein V, Laprell H, Tinnemeyer S, Petersen W (2000) Quantitative assesment of the intravascular volume of the human achilles tendon. A Orthop Scand 181:313–314

Thibièrge G, Weissenbach AJ (1911) Concrétions calcaires sous-cutanées et sclérodermie. Ann Derm Syph (Paris) 42:129

Tillmann B, Koch S (1995) Functional adaptation processes of gliding tendons. Sportverletz Sportschaden 9(2):44–50

Tillmann B (1998) Quergestreifte Muskulatur. Rauber/Kopsch, Band I, Kapitel 7: Untere Extremität. Thieme, Stuttgart New York, pp 130–171

Uthoff HK (1975) Calcifying tendonitis: an active cell mediated calcification. Virch Arch 366:51–58

Uthoff HK, Sarkar K, Maynard JA (1976) Calcifying tendinitis: a new concept of its pathogenesis. Clin Orthop 118:164–168

Uthoff HK, Sarkar K (1991) Pathology of rotator cuff tendons. In: Watson (ed) Surgery disorders of the shoulder. Churchill Livingstone, New York

Wepfer JF, Reed JG, Cullen GM, McDevitt WP (1983) Calcific tendinitis of the gluteus maximus tendon (gluteus maximus tendinitis). Skeletal Radiol 9(3):198–200

Wolff H (1902) Über eine seltene Form seniler Verkalkung. Arch Klin Chir 67:299–313

Wulle C, Heim U (1990) Peritendinitis calcarea an der Hand, ein kasuistischer Beitrag. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir 22:92–95

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muschol, M., Müller, I., Petersen, W. et al. Symptomatic calcification of the medial collateral ligament of the knee joint: a report about five cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 13, 598–602 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-004-0598-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-004-0598-1