Abstract

This paper uses register-based panel data to examine over-education amongst immigrants in Denmark. Foreign-educated immigrants are found to be more prone to over-education than both native Danes and immigrants educated in Denmark. Labour market experience reduces this risk, whereas periods of unemployment make a person more likely to accept a job for which he is over-qualified. Over-educated workers earn slightly more than their adequately matched colleagues, but less than if they had been appropriately matched in a higher level job. Foreign-educated immigrants gain the least from over-education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is well-known that immigrants in Europe tend to have lower labour market participation rates than natives (OECD 2005). A common political response to this ethnic discrepancy is to encourage immigrants to further educate themselves and to ensure that economic incentives are in place so that it pays to take a job rather than depend on state support. The underlying premise is that having a job opens the door to successful integration and that education is a key to getting a job. Whilst current immigrants are struggling to strengthen their labour market attachment, several European countries are simultaneously trying to attract new skilled migrants to work in selected professional fields that are experiencing shortages. An example is the Danish job card scheme introduced in 2002. It provides foreign nationals who have been hired for work in selected professions (e.g. doctors and nurses) immediate residence and work permits. It is against this policy background that we take a closer look at how the qualifications of immigrants already living in Denmark are being used. Three questions are addressed: (1) To what extent are immigrants over-educated and how does this compare with native Danes? (2) Why are some immigrants more likely to be over-educated than others? (3) What are the consequences of over-education for individual wages?

An individual who has more education than is required for his job is said to be over-educated. Whether or not this is a problem depends on the reason for this mismatch, whether it is a temporary or permanent situation for the individual, and whether it is a structural feature of the labour market. Being over-educated for a longer period of time will lower the labour market value of an individual’s formal qualifications if these skills become outdated. This can lead to job dissatisfaction and subsequently also lower productivity and lower wages. Over-education can have macroeconomic implications as well. The skills of over-educated workers are potentially under-utilised, and therefore, widespread over-education can be costly for the economy at large because human capital resources are inefficiently allocated leading to lower economic growth (e.g. Barrett et al. 2006).

A substantial body of empirical literature has emerged dealing with the incidence and earnings consequences of over-education. Most European studies consider the cases of Germany, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK (e.g. Korpi and Tåhlin 2006; Linsley 2005; Böhlmark 2003; Büchel and Mertens 2004; Dolton and Silles 2008). A few studies, such as Lindley (2009), Chiswick and Miller (2008), and Green et al. (2005), focus on immigrants. As far as the author is aware, there are only two studies on immigrant over-education in Denmark: Schmidt and Jakobsen (2000) and Jakobsen (2004). The first study is based on a national survey conducted amongst 30–35-year-old second-generation immigrants, who were born and educated in Denmark. Employed respondents were asked whether their job matched their education. The second study is a register-based econometric study that focuses on 28–36-year-old first-generation immigrants who came to Denmark as children in the 1970s and have therefore taken virtually all their education here. Although also a register-based econometric analysis, the current study distinguishes itself from Jakobsen (2004) by analysing two separate groups of immigrants: those educated in Denmark and those educated abroad. To assess individual over-education, Jakobsen (2004) uses a multinomial logit model to estimate the probability of an individual being in a given occupation category conditional on observed characteristics. By contrast, we use a realised matches approach, which is more common in the literature. Moreover, Jakobsen (2004) uses intra- and inter-occupational wage differentials between ethnic Danes and immigrants to draw conclusions about the earnings consequences of over-education. This present study, by contrast, uses a decomposition that is more frequently used in the over-education literature, namely the over-, required-, and under-education (ORU) wage equation, to estimate the returns to different components of an individual’s education. By applying methods widely used in the international literature, we are able to compare our results with the findings of others.

The paper proceeds as follows: The next section provides an overview of the data. Section 3 describes the econometric methods used to indentify determinants of over-education and to assess the consequences of over-education for earnings. Section 4 presents and discusses the results whilst the final section concludes.

2 Data and descriptive statistics

The empirical analysis uses two large longitudinal data sets established from administrative registers. The first data set contains information about the entire population of immigrants living in Denmark. The second data set consists of a 10% random sample of the native Danish population. Immigrants enter the register when they are provided with a social security (CPR) number. All foreign citizens—children and adults alike—who are granted a residence permit automatically receive a CPR number. The period covered is 1995–2002.Footnote 1 Key variables used in this study include labour market participation status, occupational category, hourly wages, Danish labour market experience, highest attained level of education, source of education (Denmark or a foreign country), age and for immigrants also the country of origin and year of entry. We examine first-generation, non-Western immigrants because this is the group of foreigners that has the greatest difficulties in terms of labour market integration. A first-generation immigrant is defined by Statistics Denmark as a person who is born in a foreign country and whose parents are either foreign citizens or born in a foreign country too. A second-generation immigrant is a person born in Denmark to parents that are first-generation immigrants. Since the main influx of immigrants to Denmark arrived in the late 1960s and early 1970s, second-generation immigrants are still fairly young, they are typically still undertaking full-time education, and have therefore not yet accumulated much labour market experience to enable reliable analyses. Western immigrants have stronger attachment to the labour market compared with non-Western immigrants and are not considered an integration concern compared with non-Western immigrants. See, e.g. Statistics Denmark (2009) for an overview of the current employment situation for immigrants split by first-/second-generation and by Western/non-Western origin compared with native Danes.

The study focuses on males because the labour market situation for female immigrants is very different from their male counterparts. The age group considered is 25–57. The upper age limit is set to avoid selection problems related to early retirement. Self-employed individuals, students undertaking full-time education and individuals for whom information about their highest attained education is not available, are excluded. For foreign-educated immigrants, information about their levels of education was obtained through surveys conducted by Statistics Denmark in 1999 and 2003. Immigrants were asked to classify their foreign-acquired education in categories that are also used for classifying Danish educations. The follow-up survey in 2003 represented an improvement over the initial survey in 1999. It was expanded with additional questions that could be combined to check for erroneous classifications. The aim was of course to ensure high-quality registration. See Mørkeberg (2000) for a description of methodology and findings.

Our sample consists of workers that have either a vocational or a further education because these are—by definition—the individuals that can reasonably be said to be at risk of over-education.Footnote 2 Other authors follow a similar strategy, e.g. Rubb’s (2003a, b) US sample consists of individuals with post-college schooling and Di Pietro and Urwin (2006) and Chevalier and Lindley (2009) analyse university graduates in Italy and the UK, respectively. We include wage earners that have worked fulltime for at least 2 months in a given year so as to avoid the results being affected by short-term employment spells such as summertime jobs, which may be characterised by higher degrees of over-education than more permanent jobs. Individuals employed in the military or as legislators, senior officials and managers are also excluded because these two occupational groups are strongly heterogenous.

The population is split into three subsamples: native Danes, immigrants with a Danish education and immigrants with a foreign-acquired education. Although the average ages of the three subsamples are quite similar, Table 1 reveals that there are substantial differences in terms of how many years of Danish labour market experience they have. In this context, it is important to note that Danish labour market experience is based on register data and is not self-reported. Whilst the average is almost 18 years for natives, it is only roughly 8.5 years for Danish-educated immigrants and 6.5 years for foreign-educated immigrants. As expected, the mean years since migration (YSM) is substantially higher for immigrants with a Danish education (almost 21 years) compared with immigrants with a foreign education (11 years) due to differences in the average age at migration. Table 1 also shows that the distribution of educational attainment amongst immigrants differs somewhat from that of Danes. Only 48% of immigrants with a Danish education have a vocational education compared with 66% of the native Danes. On the other hand, 41% of the Danish-educated immigrants have a medium or long further education. The corresponding figures are 26% for native Danes and 28% for immigrants with a foreign education. The summary statistics also show that, on average, foreign-educated immigrants earn the least and native Danes earn the most.

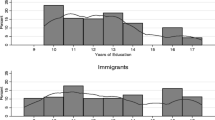

This study uses the so-called realised matches approach to determine whether a worker is adequately educated for his job or not. This approach compares each individual’s level of education with a calculated norm for his occupational category. Two different measures of a norm are used: (1) the mean method, which defines the norm as a 1-standard deviation range around the mean (following Verdugo and Verdugo 1989), i.e. workers are over-educated if their length of education is greater than 1-standard deviation above the mean for their specific occupation, and (2) the mode method, which defines the norm as the modal (i.e. most frequent) value, i.e. a worker is over-educated if his length of education is greater than the modal value for his occupation.

The realised matches approach measures the outcome of the actual matching process (i.e. the interplay between labour demand and supply) as determined by current hiring standards and labour market conditions. An obvious disadvantage is that it is a purely statistical approach to defining what level of education is ‘required’ to perform a particular job. Also, in the case of the mean-based approach, the standard band of ± 1 standard deviation is arbitrary and imposes symmetry on the distribution of years of schooling. In the case of the mode approach, it requires a fine level of dissaggregation of occupational categories in order to be meaningful. Even then it can be difficult to avoid, e.g. two difference lengths of schooling that are almost equally frequent in a given occupational category. Alternatives to the realised matches approach are the job analysis and worker self-assessment methods. For a discussion of their strengths and weaknesses, see, e.g. Hartog (2000), Rubb (2003a) or Verhaest and Omey (2004).

Occupations are classified using the DISCO code at the three-digit level. To avoid unreliable results due to small cell sizes in certain occupations, we have chosen to place individuals employed in three-digit categories with less than 100 observations in their more aggregate two-digit counterpart. This gives us 114 occupational categories altogether. The mean-based limits and the modal values defining the norms, or ‘required’, levels of education are calculated on the basis of employees with a Danish education. This is a useful reference point because these are the educations that Danish employers are familiar with. Hence, in this context, an individual is said to be over-educated if he possesses more education than the ‘Danish education norm’ in his occupational category. As a robustness check of this definition, we have calculated a general education norm, which includes foreign-educated immigrants. The differences in the shares of over-educated individuals in each of the sub-populations are less than 2 percentage points.Footnote 3

We find that immigrants are substantially more prone to over-education than native Danes, with foreign-educated immigrants more often classified as over-educated than Danish-educated immigrants. Using the mean-based method, Table 1 reveals that 39% of the foreign-educated immigrants are over-educated compared with 20% of the Danish-educated immigrants and 15% of the native Danes. Using the mode approach, the level of over-education is somewhat higher—47% for foreign-educated immigrants, 40% for Danish-educated immigrants and 33% for native Danes.Footnote 4 Other authors also find that the incidence of over-education varies by method of measurement (see, e.g. Bauer 2002 for the case of Germany) and that it differs between natives and immigrants. Green et al. (2005), for example, find that less than 10% of native Australians are over-educated whilst the share is 19–27% for immigrants and 32–40% for immigrants from non-English speaking countries. For the UK, Lindley and Lenton (2006) find that 63% of male immigrants are over-educated against 37% of male natives. This finding of a native-immigrant differential is not surprising if one consults theories of discrimination and if one believes that a certain level of discrimination is present in the labour market. If immigrants find it more difficult to acquire any job at all due to discrimination, they are more likely to accept a job that does not match their qualifications (Jakobsen 2004).

The finding that fewer Danish-educated immigrants are over-educated compared with foreign-educated immigrants is probably due to a combination of at least four effects: First, employers are more confident about employing individuals with a Danish education. They are familiar with the content of the education and are better able to assess the quality hereof because they know the grading and evaluation systems being used. Second, individuals who have completed a Danish education have proved to master the Danish language to a certain level. Third, native Danes (and immigrants who have lived in Denmark for a long time) are presumed to have better networks which they can use in their job search. Fourth, some migrants with foreign-acquired education could have migrated because they were over-educated in their home country, have moved in hope of obtaining a better match, but have been unsuccessful. Nonetheless, the finding that foreign-educated immigrants far worse than Danish-educated immigrants could in principle be more apparent than real. This would be true if the apparent over-education experienced by these individuals is in fact compensating for lower quality of these foreign credentials. Unfortunately, for this study, we do not have a way of assessing the true quality of individual immigrant’s foreign-acquired qualifications.

The phenomenon of over-education seems to be quite persistent. Table 2 shows job-to-education matches 5 years later for workers who were over-educated in each of the years 1995–1997. Using the mean approach, we find that almost 70% of native Danes are still over-educated 5 years later. The share is slightly higher for immigrants with a foreign education (up to around 85%). Immigrants with a Danish education appear somewhat more successful in attaining a better matched job with time than both native Danes and foreign-educated immigrants. Using the mode approach, the mobility out of over-education and into adequate job-to-education matches appears to be less for all three subpopulations. For other results on persistence, see, e.g. Böhlmark (2003) and Rubb (2003b).

3 Econometric analysis

3.1 Determinants of over-education

This section describes the econometric method we use to identify some of the reasons why there are such large differences in the incidence of over-education amongst the three sub-samples. Based on our available data, we can formulate some expectations about which factors are important in determining an individual’s risk of being over-educated. Experience in the Danish labour market should increase the chance of an appropriate match because the individual has had time to reveal his ‘true’ skills and productivity. The effect of years since migration can pull results in both directions. On the one hand, an immigrant who has spent a long time in the host country should have better language skills, knowledge about the functioning of the labour market and good contacts to assist in the job search process. On the other hand, how this time is spent is crucial. If much of the time is spent working, taking language courses, upgrading one’s qualifications etc., this will reduce the risk of over-education. If time is spent in either unemployment or completely outside the labour force, acquired skills can become obsolete, a person tends to lower his reservation wage and therefore become more willing to take on a job that he is formally over-qualified for. The younger an immigrant was when he moved to Denmark, the easier it is for him to learn the language and build up a network that can be used in a job search.

Beyond what our data can capture, previous research shows that unobserved individual heterogeneity is important (see, e.g. Böhlmark 2003; Bauer 2002). Within a group of workers with the same education, some are more skilled (in aspects that are not captured by formal education), more motivated and more able than others. On the one hand, over-educated individuals may be the most motivated and eager to work and thereby demonstrate their true skills and qualifications on the job. On the other hand, the over-educated may be so precisely because they have low motivation or other characteristics that make them unable to get a job that matches their formal qualifications. Examples of relevant, but for the researcher unobservable, personal characteristics could be health, management skills, ability to work in teams, creativity and IT skills.

Another unobservable aspect of human capital is the true quality of foreign-acquired qualifications. Low educational quality, credential problems and mismatches in technological requirements can mean that education and experience obtained in certain other countries are not as productive in the host country as education and experience acquired here (Ferrer et al. 2006; Mattoo et al. 2005; Friedberg 2000). Moreover, there may be an element of self-selection in the over-education process in the sense that those who experience over-education in their home country (see, e.g. Quinn and Rubb 2005, 2006) might emigrate in hope of obtaining a better match. But because being over-educated can result in skills becoming obsolete, such a person is also at risk of becoming over-educated in his new host country too. Unfortunately, we do not have information about over-education prior to arrival in Denmark.

There are several possible strategies to account for such unobserved individual heterogeneity. Chevalier (2003) and Chevalier and Lindley (2009), for example, use residuals from regressions of first job earnings to proxy unobserved skills of graduates. Korpi and Tåhlin (2006) include survey-based information on health and verbal ability as proxies. We do not have survey information from which to obtain such proxies, but the panel aspect of our data does allow us to deal with unobserved individual heterogeneity.

To identify key determinants of over-education, we estimate a logit model for the probability of being over-educated (the alternative being either adequately or under-educated). The model includes the unobserved individual effect, c i , which is interpreted as capturing features of an individual such as cognitive ability, motivation etc. that are given and assumed constant over time. It is assumed that the x it variables are strictly exogenous conditional on the unobserved effect c i . We estimate the model using the random effects estimation method, despite its restrictive assumption that c i is uncorrelated with x it . Allowing correlation between c i and x it , the fixed effects approach is more robust than the random effects approach, but it also entails excluding time-constant factors such as ethnicity or age at migration. Another downside of the fixed effects model—and one that is potentially more serious than the previous one—is that identification relies on individual variation over time, and it thereby discards information represented by between-person variation (Wooldrige 2002). A fixed effects approach would only identify the determinants of over-education from information on individuals who change their level of education, their job category or both within the sample period. This is a very unattractive feature for our current study since only few persons in our sample do that and those who do are typically out of our sample for several years whilst they are, e.g. enrolled in education. We therefore choose to estimate the model using a random effects approach.

Assuming a normal distribution, N(0, \(\sigma _c^2 )\) for the random effects c i, the estimated model is:

Separate models are estimated for the three subsamples: native Danes, Danish-educated immigrants and foreign-educated immigrants. As explanatory variables, we include Danish labour market experience, level of education and year dummies. For immigrants, we also include years since migration, age at migration and eight ethnicity dummies. Note that we have information about actual (register-based) labour market experience in Denmark as opposed to potential labour market experience, which is the most common approach taken in the literature due to lack of data. It is also important to stress that the relationship being estimated is not necessarily causal but serves to identify important correlations in the data.

3.2 Earnings consequences of over-education

To investigate the implications of over-education for individual wages, we estimate a set of random effects linear regression models. Following a similar line of reasoning as in Section 3.1, a random effects approach is chosen because it relies on between-person variation in job-to-education match (i.e. adequately, over- or under-educated) as opposed to within-person variation in job-to-education match over time. Since only very few individuals in our sample change their job-to-education match over the study period, a fixed effects approach would therefore be inappropriate. Following the existing literature, we take the Mincer earnings equation as our starting point (see, e.g. Chiswick and Miller 2008; Heckman et al. 2003; Mincer 1974; Willis 1986), which regresses log earnings (\(\emph{w}_{it}\)) on a constant term, a linear term in years of schooling (s it ), plus linear and quadratic terms in years of labour market experience (x it ). Unobserved individual effects υ i are included to capture differences in unobserved earnings ability.

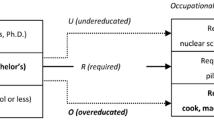

The over-education literature decomposes the actual years of schooling variable into three parts (ignoring subscripts): s = s R + s O − s U, where s R is required schooling (i.e. the number of years of schooling judged adequate for the job), s O is over-schooling (i.e. the number of years of schooling the individual might have in excess of s R) and s U is under-schooling (i.e. the number of years of schooling the individual might have less than s R; Duncan and Hoffman 1981; Sicherman and Galor 1990).

With the mean method, the upper and lower limits of the mean ± 1 standard deviation, respectively, are used to calculate the number of over-education years and under-education years for each individual. For adequately matched individuals, the required, or adequate, level of education is equal to the person’s actual level of education for both the mean and the mode method. Introducing this decomposition yields the so-called ORU equation, with reference to the three components of schooling:

The coefficient α 1 indicates the return to schooling for adequately matched workers. The coefficients α 2 and α 3 are to be interpreted in conjunction with α 1 to obtain the total impact of education for mismatched workers. This decomposition has the attractive conceptual property that it combines information on attained and required education whilst retaining the continuous character of both dimensions. In other words, α 2 and α 3 are to be interpreted relative to workers in the same occupation who are adequately matched.

The ORU equation reveals that the traditional Mincer Eq. 2 implicitly imposes the following restriction: H1: α 1 = α 2 = α 3. Accepting hypothesis H1 amounts to saying that the return to (an additional year of) schooling is the same for all individuals with the same level of schooling, regardless of whether the individual is in a job that matches his qualifications or not. It is his actual schooling that matters—not the match. Another testable hypothesis is: H2: α 2 = α 3 = 0. This amounts to saying that ‘excess’ and ‘deficit’ years of schooling (compared to job requirements) are neither rewarded nor penalised. It is the educational requirements of the job (s R) alone that affect earnings. In addition to the schooling variables, our estimations of the ORU equation control for the same explanatory variables used in the logit models described in the previous section.

In empirical estimation of the Mincer (and related) earnings equation, schooling is treated as exogenous despite the fact that education is clearly an endogenous choice variable in the underlying human capital theory. This is also the approach taken here and is no different from the rest of the immigrant earnings literature which rarely addresses educational endogeneity (see, e.g. Ferrer et al. 2006).

4 Results

4.1 Determinants of over-education

Contrary to most other over-education studies, we are able to account directly for labour market experience in the host country, and therefore, we have chosen to include this as a main explanatory variable along with the level of education. For immigrants YSM, YSM-squared, age at migration and eight ethnic dummies are also included. It could be argued that labour market experience is potentially endogenous in the context of over-education, since over-educated individuals conceivably have unobserved characteristics that are not valued in the labour market, thereby also making them more at risk of unemployment. As a robustness check, we have estimated the model with age and age-squared instead of experience and experience-squared. The estimated coefficients of the remaining variables in the model were found to be robust to this change.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, it must be stressed that the relationship estimated is not necessarily causal but serves to identify important correlations in the data.

The results of the random effects logit model estimations are shown in Table 3 (mean method and mode method). For native Danes, labour market experience clearly reduces the risk of being over-educated when using the mean method. The conclusion is less clear when using mode method, with an insignificant coefficient for experience and a significantly negative coefficient for experience-squared. A joint test, however, shows that they should not jointly be left out of the model.

Danish labour market experience is very important in reducing the risk of over-education for immigrants as well. A joint test in the model for Danish-educated immigrants using the mean method shows that experience and experience-squared are not jointly zero. The absolute size of the coefficients is greater for foreign-educated immigrants, indicating that Danish labour market experience is relatively more important for this group compared with Danish-educated immigrants. The intuition behind this result is that being in a job is the only real way a foreign-educated immigrant can demonstrate his true skills to a Danish employer and thereby move up the ladder if he was initially employed at a level below his formal qualifications.

Conditional on labour market experience in Denmark, YSM essentially measures un-/non-employment in Denmark. Hence, the positive, but decreasing, effect of YSM can be interpreted as follows: The longer time a person has spent un-/non-employed, the more likely he is to lower his reservation wage, thereby making him more likely to accept a job for which he is over-qualified. Once again, the absolute size of the coefficients is greater for foreign-educated immigrants than for Danish-educated immigrants. In other words, unemployment is particularly harmful for the chances of foreign-educated immigrants achieving an appropriate job-to-education match. The positive effect of YSM on the probability of over-education increases until YSM equals 26 for foreign-educated immigrants, compared with an average of 11 YSM for this group (the corresponding figures are 38 and 21, respectively, for Danish-educated immigrants). Uncertainty about the true quality of foreign-acquired skills makes it even more important that they are demonstrated on the job as quick as possible if these people are not to end up in unsatisfactory jobs. Joint tests of the coefficients for YSM and YSM-squared for both the mean- and the mode-based models for the Danish-educated immigrants shows that the YSM variables should not be left out of the model.

To illustrate the importance of accumulating Danish labour market experience in order to increase an individual’s chances of obtaining an appropriate job-to-education match, we have calculated the consequences of two labour market scenarios for two types of ‘typical’ immigrants (Table 4). The two types are distinguished by where they have obtained their education: in Denmark or abroad. The two scenarios look 5 years into the future. In the positive scenario, the individual is employed in all 5 years. In the negative scenario, he is unemployed in all 5 years. For a Danish educated immigrant, being employed in all 5 years reduces the risk over education by 2.6%-points (becoming 17.5% compared with an outset of 20.1%), whereas being unemployed in all 5 years increases the risk to 22.7%. The relative effects are larger for the average foreign-educated immigrant. From an outset of 38.9%, the risk of over-education is reduced to 30.1% if the individual stays on the labour market the next 5 years. If he is so unfortunate to lose his job and remain unemployed for the next 5 years, his risk of over-education increases to 57.4%.

For Danish-educated immigrants, the higher the age at migration, the greater the risk of over-education. Comparing two Danish-educated immigrants with different ages at migration, the one who came to Denmark at a relatively young age presumably has a better knowledge of the Danish language, education system and labour market compared to the one who arrived at a later age, thereby making it easier to obtain an appropriate job-to-education match. By contrast, the mean-based results show that foreign-educated immigrants that arrive in Denmark at a relatively old age are less at risk of becoming over-educated compared with foreign-educated immigrants that arrive in Denmark at a relatively young age. To explain this result, one could think of age at migration as a proxy for labour market experience obtained prior to arrival in Denmark. To the extent that this labour market experience can be documented to a potential employer, this will help ensure a better match. By contrast, it can be more difficult for a recently educated individual with foreign university papers but without any foreign labour market experience to convince a Danish employer to hire him. This result should, however, be interpreted very cautiously since the coefficient for age at migration is not significant using the mode approach for the group of foreign-educated immigrants.

The probability of being over-educated does not increase monotonically with the level of education for natives and immigrants with a Danish education. Individuals with medium-length further educations obtained in Denmark have a lower risk of over-education compared with individuals with either a short or a long further education. An explanation for these results is that these types of education are typically vocationally oriented and include educations such as the training of nurses, school teachers and kindergarten teachers—all of which are qualifications directly oriented towards specific occupations.

In all our estimations, we find that the correlation coefficient rho is large and highly significant. This means that there are substantial unobserved individual effects that affect the probability of being over-educated—a conclusion that is in line with Bauer (2002).

To test the robustness of our results, we have estimated the models with different combinations of the experience, age, YSM, and age-at-migration variables. We find that the signs of these coefficients are consistent across estimations when using the mean method. In models with age, YSM and age at migration or just age and age at migration, we cannot reject the joint hypothesis that age and age-squared can be left out of the model, reaffirming our decision to use experience and experience-squared instead of age and age-squared. Using the mode approach, the coefficient estimates for experience, age and YSM are generally stable but unstable for the age-at-migration coefficient, and therefore, the mode-based results should be interpreted with much care.

To sum up, our results show that it is important for both groups of immigrants to gain experience in the Danish labour market to reduce their risk of becoming over-educated, but it is most important for foreign-educated immigrants. If they are to obtain good job-to-education matches, they must simply get a foot inside the door and demonstrate their skills on the job. These findings fit well with other studies which consider immigrants with foreign-acquired qualifications such as Battu and Sloane (2004) and Lindley and Lenton (2006).

4.2 Earnings consequences of over-education

The main results of the random-effects wage regressions are presented in Table 5—the complete results are available on request. In the first set of regressions (‘standard’), we include attained (actual) schooling as a single variable. In the second and third sets of regressions (‘mean’ and ‘mode’), we split attained (actual) years of schooling into the three components: adequate education, over-education and under-education using the mean and the mode methods, respectively.

Starting with the standard regression, we find that the return to each year of schooling for immigrants with a Danish education (7.2%) is virtually equivalent to that of native Danes (7.5%). The returns to schooling for immigrants with a foreign education are notably lower (4.3%). When splitting years of acquired schooling into the three ORU components with the mean approach, we find that there are only minor difference between the estimated coefficients on required schooling for Danes and immigrants. We do, however, find striking differences regarding the returns to over-education. Danish-educated immigrants are rewarded by only a 5.2% increase in wages per year of over-education, whereas native Danes are rewarded by 5.9% per year of over-education. In other words, the penalty for being over-educated is slightly more severe for Danish-educated immigrants compared with native Danes. Immigrants with a foreign education are penalised much harder for being over-educated in that each year of excess education brings about only 0.8% higher wages.

Using the mode approach, we find that the return to required education is markedly lower for foreign-educated immigrants compared to the other two groups and that there is no significant difference between returns to required and over-education. Compared with the mean approach, it seems as if the mode approach is unable to capture important differences related to earnings ability. A reason for this could be that the mode is a rather rigid definition, which cannot take account of two or more ‘typical levels’ of education within the same occupational category. As we saw in Table 1, this means that a large share of workers are categorised as over-educated—perhaps more than what is plausible. As a consequence, this means that each of the mode-based ORU categories lump together more diverse workers—also in terms of earnings ability. The mean method is more ‘smooth’ and by definition ‘pulls in’ more workers into the group of adequately matched workers due to its band approach. Consequently, fewer are classified as over-educated and the workers placed in each of the three ORU categories are probably more alike—at least in terms of earnings outcomes. Since the Danish labour market is characterised by strong labour unions and (by international standards) a narrow wage dispersion, there is reason to believe that the mean approach, with its virtually identical coefficients for required education for all three subgroups, yields the most plausible results.

Another possible reason for the sensitivity of the results for foreign-educated immigrants with respect to definition of over-education (mean or mode) is that information about their levels of education is self-reported. In principle, this information could be misreported despite the efforts made by Statistics Denmark to ensure high-quality recordings (cf. Section 2). One should therefore be cautious when interpreting these results.

Tests of the two hypotheses H1: α 1 = α 2 = α 3 and H2: α 2 = α 3 = 0 put forth in Section 3.2 are strongly rejected for all estimations, which simply means that both required and acquired education are part of the wage story. Our results are generally in accordance with three of the ‘stylised facts’ in the literature (with the one exception of the mode-based model for foreign-educated immigrants where the effects of over-education and required education are indistinguishable):

-

1.

Returns to adequate schooling are higher than returns to actual education.

-

2.

Returns to over-education are positive but smaller than to adequate education.

-

3.

Returns to under-education are negative and smaller in magnitude than the returns to adequate education. (Hartog 2000; Rubb 2003a; Harmon et al. 2000)

In other words, one typically finds that over-educated workers earn more than adequately matched workers in the same kinds of jobs but less than adequately matched workers with similar amounts of education. Our results for native Danes are quite similar to the average returns reported in the meta-analysis by Rubb (2003a). He finds that the unweighted average returns to required education, over-education and under-education are 9.5%, 5.2% and −4.8%, respectively. Our mean-based results are not far from these, although the returns to required education are somewhat lower.

Danish labour market experience has virtually the same positive effect (coefficients are all around 0.03 and significant at the 1% level) on wages for both immigrant sub-groups. The coefficients for years since migration and age at migration are significantly negative but smaller in absolute magnitude (∣ 0.005 ∣ − ∣ 0.009 ∣ for YSM and YSM2, ∣ 0.001 ∣ − ∣ 0.003 ∣ for age at migration) than the coefficients for experience (not reported in the table for brevity). As discussed earlier, conditional on labour market experience, years since migration represents time spent in un-/non-employment. All these effects on wages are very small, and this is a simple consequence of the fact that the Danish labour market is characterised by a high degree of unionisation resulting in a very narrow wage spread by international standards.

5 Conclusion

This paper has taken a closer look at how the qualifications of immigrants living in Denmark are used in the labour market. This has led to a number of interesting results concerning the incidence and consequences of over-education. Our first question was to which extent are immigrants employed in jobs for which they are formally over-qualified. We used two different measures based on a realised job-to-education matches approach. The mean-based method classified 39% of the foreign-educated immigrants as over-educated compared with 20% of the Danish-educated immigrants and 15% of the native Danes. The mode-based method results in somewhat higher shares—47% for foreign-educated immigrants, 40% for Danish-educated immigrants and 33% for native Danes. These findings are consistent with the existing literature.

To understand why some individuals are more likely to become over-educated than others, we estimated a set of random effects logit models. We found that Danish labour market experience is extremely important in reducing the probability of becoming over-educated—particularly so for foreign-educated immigrants. Conditional on experience, we find that the longer time an immigrant has been in Denmark, the more likely it is that he will take on a job that he is formally over-qualified for. This is a reflection of the fact that as time spent in unemployment passes, a person tends to lower his reservation wage, thereby becoming more willing to accept a lower level job. We also found that age at migration increases the risk of over-education for Danish-educated immigrants but tends to reduce it for foreign-educated immigrants. Although one must generally be cautious about the results for foreign-educated immigrants because information about their education levels is self-reported, this latter effect is interpreted as reflecting the fact that foreign-educated immigrants are more likely to have labour market experience prior to arrival in Denmark, which—if it can be documented—can probably help them obtain an appropriate match. Our results also suggest that there is a substantial amount of unobserved heterogeneity meaning that we still have a lot to learn about the determinants of over-education.

Our final question concerned the earnings consequences of over-education. For this purpose, we estimated a series of random effects ORU wage regressions. Our results are in accordance with expectations, i.e. that an over-educated worker earns more than an adequately matched worker in the same type of job, but less than he could earn if he secured a job that matched his level of schooling. In particular, when using the mean method, we find that the relative penalty for over-education is much larger for immigrants with foreign credentials.

Our results lead us to discuss three policy considerations. First of all, our results suggest that it is important to strengthen the focus on how to make the best possible use of foreign qualifications in the Danish labour market. One possibility is for all immigrants that arrive with foreign-acquired education and/or labour market experience to have their qualifications assessed officially. It is conceivable that an official evaluation could help an immigrant find a job that matches his ‘true’ qualifications and skills. To be fair, a note of caution is warranted. Assessing immigrants’ qualifications through, e.g. tests may in fact put them at an unintentional disadvantage since many people (immigrants or natives) would probably fail exams on qualifications obtained in the past.

Closely related to this warning is our second policy consideration, which deals with the possibility of offering supplementary training to upgrade and increase the relevance of foreign-acquired qualifications for a Danish context. Our results show that years spent in un-/non-employment significantly increases the risk of being over-educated for foreign-educated immigrants. Naturally, it takes time to get settled and learn a new language, but during this period, there is a risk that an immigrant’s formal skills become obsolete and in need of an update. A third policy consideration also has to do with ensuring the continued relevance of the educational backgrounds of foreign-educated immigrants. They must be able to enter the labour market as quickly as possible, and therefore, intensive Danish language training ought to be top priority for this group of immigrants. Short-to-medium run implementation costs of such policy measures must be weighed against the long-run expected benefits—at both the individual and the societal level—of ensuring appropriate job-to-skill matches.

Notes

The dataset stops in 2002 because the sources used to construct the Danish ISCO occupation code (DISCO) change, causing the variable to become increasingly unreliable with many missing values.

When using the entire sample (i.e. including individuals with primary and secondary schooling as their highest attained level of education), the mean method (described in the main text below) shows that the share of over-educated individuals is zero for individuals at these levels of education.

The limits and values defining ‘required’ education using the mean- and mode-based approaches, respectively, and the shares of over-educated workers by occupational category and ethnicity are available on request.

The rates of over-education are not sensitive to increasing the lower age limit to 30 years. Using the mean approach, the shares of over-educated Danes, immigrants with Danish education and immigrants with foreign education are 15.1%, 20.5% and 40.4%, respectively. Using the mode approach, the shares of over-educated Danes, immigrants with Danish education and immigrants with foreign education are 33.2%, 40.7% and 47.6%, respectively.

Some authors attempt to deal with a potentially endogenous explanatory variable by using an instrument. Often family-related instruments are chosen, but they are often not yet convincing and turn out to be weak and/or invalid. Korpi and Tåhlin (2006), for example, use sibship size, place of residence during childhood, economic problems and disruption in the family of origin as instruments but find that they are weak. Weak instruments lead to imprecise results and choosing an invalid instrument may even aggravate a possible bias. In this analysis, we therefore refrain from using instrumental variables methods.

References

Barrett A, Bergin A, Duffy D (2006) The labour market characteristics and labour market impacts of immigrants in Ireland. Econ Soc Rev 37(1):1–26

Battu H, Sloane PJ (2004) Overeducation and ethnic minorities in Britain. Manchester Sch 72(4):535–559

Bauer T (2002) Educational mismatch and wages: a panel analysis. Econ Educ Rev 21(3):221–229

Böhlmark A (2003) Over- and undereducation in the Swedish labour market. Incidence, wage effects and characteristics 1968–2000. Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), Stockholm University, Stockholm

Büchel F, Mertens A (2004) Overeducation, undereducation and the theory of career mobility. Appl Econ 36(8):803–816

Chevalier A (2003) Measuring over-education. Economica 70(279):509–531

Chevalier A, Lindley J (2009) Over-education and the skills of UK graduates. J R Stat Soc, Ser A Stat Soc 172(2):307–337

Chiswick BR, Miller PW (2008) Why is the payoff to schooling smaller for immigrants? Labour Econ 15(2):1317–1340

Di Pietro G, Urwin P (2006) Education and skills mismatch in the Italian graduate labour market. Appl Econ 38(1):79–93

Dolton P, Silles M (2008) The effects of over-education on earnings in the graduate labour market. Econ Educ Rev 27(2):125–139

Duncan GJ, Hoffman SD (1981) The incidence and wage effects of overeducation. Econ Educ Rev 1(1):75–86

Ferrer A, Green DA, Riddel WC (2006) The effect of literacy on immigrant earnings. J Hum Resour 41(2):380–410

Friedberg RM (2000) You can’t take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. J Labor Econ 18(2):221–251

Green C, Kler P, Leeves G (2005) Immigrant overeducation: evidence from recent arrivals to Australia. Econ Educ Rev 26(4):420–432

Harmon C, Oosterbeek H, Walter I (2000) The returns to education. A review of evidence, issues and deficiencies in the literature. Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics and Political Science, London

Hartog J (2000) Over-education and earnings: where are we, and where should we go? Econ Educ Rev 19(12):131–147

Heckman JJ, Lochner LJ, Todd PE (2003) Fifty years of Mincer earnings regressions. NBER Working Paper 9732, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Jakobsen V (2004) Overeducation or undereducation and wages of young immigrants in Denmark. In: Jakobsen V (ed) Young immigrants from the former Yugoslavia, Turkey and Pakistan: educational attainment, wages and employment. PhD thesis, Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business

Korpi T, Tåhlin M (2006) Skill mismatch and wage growth. Mimeo. Institutet för Social Forskning (SOFI), Stockholms Universitet

Lindley J (2009) The over-education of UK immigrants and minority ethnic groups: evidence from the Labour Force Survey. Econ Educ Rev 28(1):80–89

Lindley J, Lenton P (2006) The over-education of UK immigrants: evidence from the labour force survey. Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series, SERP Number 2006001

Linsley I (2005) Cases of overeducation in the Australian labour market. Aust J Labour Econ 8(2):121–143

Mattoo A, Neagu IC, Özden Ç (2005) Brain waste? educated immigrants in the US labor market. Policy Research Working Paper No 3581, World Bank, Washington, DC

Mincer J (1974) Schooling, experience, and earnings. NBER, New York

Mørkeberg H (2000) Indvandrernes uddannelse (The educational attainment of immigrants—in Danish). Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen

OECD (2005) Recent trends in international migration. Annual report, 2004 edn, OECD, Paris

Quinn M, Rubb S (2005) The importance of education-occupation matching in migration decisions. Demography 42(1):153–167

Quinn M, Rubb S (2006) Mexico’s labor market: the importance of education-occupation matching on wages and productivity in developing countries. Econ Educ Rev 25(2):147–156

Rubb S (2003a) Overeducation in the labor market: a comment and re-analysis of a meta-analysis. Econ Educ Rev 22(6):621–629

Rubb S (2003b) Overeducation: a short or long run phenomenon for individuals? Econ Educ Rev 22(4):389–394

Schmidt G, Jakobsen V (2000) 20 år i Danmark (20 years in Denmark). SFI Report no 00:11, The Danish National Institute of Social Research (SFI)

Sicherman N, Galor O (1990) ‘Overeducation’ in the labor market. J Polit Econ 98(1):169–192

Statistics Denmark (2009) Indvandreres og efterkommeres tilknytning til arbejdsmarkedet 2008 NYT fra Danmarks Statistik. Nr 125, 18 Marts 2009

Verdugo R, Verdugo N (1989) The impact of surplus schooling on earnings. J Hum Resour 24(4):629–643

Verhaest D, Omey E (2004) What determines measured overeducation? Working paper 04/216, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Ghent University, Belgium

Willis RJ (1986) Wage determinants: a survey and reinterpretation of human capital earnings functions. In: Ashenfelter O, Layard D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 1. Elsevier, Oxford

Wooldrige JM (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. The MIT, Cambridge

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank two anonymous referees for constructive comments and useful suggestions on earlier versions of the paper. I would also like to acknowledge the advice and suggestions provided by my colleagues Eskil Heinesen and Gabriel Pons Rotger. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nielsen, C.P. Immigrant over-education: evidence from Denmark. J Popul Econ 24, 499–520 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0293-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0293-0