Abstract

Purpose

To use the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning to measure disability following critical illness using patient-reported outcomes.

Methods

A prospective, multicentre cohort study conducted in five metropolitan intensive care units (ICU). Participants were adults who had been admitted to the ICU, received more than 24 h of mechanical ventilation and survived to hospital discharge. The primary outcome was measurement of disability using the World Health Organisation’s Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. The secondary outcomes included the limitation of activities and changes to health-related quality of life comparing survivors with and without disability at 6 months after ICU.

Results

We followed 262 patients to 6 months, with a mean age of 59 ± 16 years, and of whom 175 (67%) were men. Moderate or severe disability was reported in 65 of 262 (25%). Predictors of disability included a history of anxiety/depression [odds ratio (OR) 1.65 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22, 2.23), P = 0.001]; being separated or divorced [OR 2.87 (CI 1.35, 6.08), P = 0.006]; increased duration of mechanical ventilation [OR 1.04 (CI 1.01, 1.08), P = 0.03 per day]; and not being discharged to home from the acute hospital [OR 1.96 (CI 1.01, 3.70) P = 0.04]. Moderate or severe disability at 6 months was associated with limitation in activities, e.g. not returning to work or studies due to health (P < 0.002), and reduced health-related quality of life (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Disability measured using patient-reported outcomes was prevalent at 6 months after critical illness in survivors and was associated with reduced health-related quality of life. Predictors of moderate or severe disability included a prior history of anxiety or depression, separation or divorce and a longer duration of mechanical ventilation.

Trial registration: NCT02225938.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing numbers of patients are surviving critical illness [1]. These survivors often experience long-term physical, cognitive and mental health impairments known as post-intensive care syndrome [2]. While the impact of critical illness is profound, there are limitations in our ability to assess functional recovery of survivors in person, with many studies reporting large amounts of loss to follow-up [3]. The number of patients with ongoing disability, and the relationship between health-related quality of life and disability, is poorly described in many populations [4].

An important goal of contemporary healthcare is to minimise the risk of ongoing disability as well as other outcomes such as healthcare costs and hospital readmissions [2]. This may be particularly important in higher-risk patients admitted to intensive care (ICU) for invasive medical therapies, such as mechanical ventilation. Patient-centred care requires that clinicians measure outcomes that matter most to patients, and this can be greatly facilitated by incorporating patient-reported outcomes [5]. That is, the patients’ experiences of disability, functioning and health-related quality of life, including participation and limitations in activities [6, 7]. The quality of survival following critical illness has been identified as one of the largest health challenges for these patients [8]; however, current definitions of disability make distinction between physical, mental or cognitive impairment caused by a health condition and the impact that impairment has on the person’s ability to work, care for themselves or interact with society [9]. The World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health defines disability as “difficulties in any area of functioning as they relate to environmental and personal factors” [7]. The measurement of disability and functioning is a different concept to health-related quality of life and the measurement of subjective well-being (Fig. 1), The World Health Organisation’s Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS) was developed to measure disability cross-culturally and for disease-related states across six major life domains: cognition, mobility, self-care, interpersonal relationships, work and household roles, and participation in society [10]. It has been tested for concurrent validity against the Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Short Form-36 and the WHOQoL and it has been used to assess disability following trauma, stroke, surgery, post-traumatic stress in veterans and in chronic diseases [11,12,13,14,15].

The aim of this study was to measure key components of the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning (ICF) [7] relevant to survivors of critical care using patient-reported outcomes [16]. The primary outcome was the incidence of moderate to severe disability at 6 months after ICU admission as measured by patient-reported rate of global function and disability (impairment of function) using the World Health Organisation’s Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (12-level). The secondary outcomes included the limitation of activities, including return to work, and changes to health-related quality of life in survivors at 6 months after ICU.

Methods

This study was designed with reference to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies Guidelines: The STROBE checklist [17]. Human research ethics committee approval was obtained at all sites, with informed consent for data collection, as per local requirements (NCT02225938).

Study design

This was a prospective, multicentre, inception cohort study with retrospective enrolment from the hospital clinical information system of ICU survivors, and prospective, centralised measurement of patient-reported outcomes.

Setting

The study was conducted in five metropolitan ICUs in the State of Victoria, Australia, including three public tertiary teaching hospitals and two private hospitals. The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University performed study management.

Participants

From the date of human ethical approval for a consecutive period of 4 months at each site, we identified all eligible patients from the hospital clinical information system. Patients were eligible if they had been admitted to the ICU, received more than 24 h of mechanical ventilation and survived to hospital discharge. We excluded patients who were aged less than 18 years old, who had a proven or suspected acute primary brain process that was likely to result in global impairment of consciousness or cognition (e.g. traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid haemorrhage, stroke or hypoxic brain injury after cardiac arrest), who did not speak English. We excluded data from any second or subsequent readmission to ICU during the index hospital admission.

Each site identified eligible patients from the hospital clinical information system. These patients were contacted initially by mail to invite them to participate in the study and then by telephone to gain consent and to collect patient-reported outcomes. Participants who agreed to be included in the study also consented to the use of hospital and ICU level information.

Demographic and hospital variables

Demographic and hospital data were extracted from hospital information systems, and included age, gender, admission diagnosis from hospital coding data, the duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay in ICU and hospital and discharge destination. Illness severity was measured with the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II and III) score and comorbidities using the APACHE II and III definitions [18].

Patient-reported outcomes

Six months after ICU admission, we collected patient-reported outcome data via telephone interview. Outcome data collected included global function and disability (the World Health Organisation’s Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS II, 12 item) [19], health status prior to and at 6 months after the ICU admission (EQ-5D-5L™) [20], cognitive function (Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, TICS) [21], anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS) [22], post-traumatic stress disorder (Impact of Event Scale–Revised, IES-R) [23] and return to work (WHODAS II) (Table 1). Data were entered into an electronic data capture system (REDCap—Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, USA) [24]. Patient-reported data were collected centrally by telephone with trained outcome assessors located at the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre, Monash University who were blinded to the details of the patient’s ICU stay.

Statistical analysis

Data were initially assessed for normality. Group comparisons were performed using chi-square tests for equal proportion, Student t tests for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon rank sum tests otherwise with results reported as N (%), mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range] respectively. Each of the 12 items on the WHODAS were scored from 0 to 4. A total score out of 48 was converted to a percentage [25]. The WHODAS II score was dichotomised into none or mild disability (WHODAS score 0–24%) versus moderate to severe disability (WHODAS score 25–100%) [19]. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using the WHODAS II score dichotomised into no disability (WHODAS 2.0 score of 0–4%) versus any disability (i.e. mild, moderate or severe disability with a WHODAS 2.0 score of 5–100%). Disability-free survival was calculated from the cohort of enrolled patients and deceased patients, where patients who scored less than 25% on the WHODAS and survived to 6 months were described as “disability-free”. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors independently associated with moderate to severe disability with results reported as odds ratios (95% CI). Multivariable models were constructed using both stepwise selection and backwards elimination techniques before undergoing a final assessment for clinical and biological plausibility with all variables considered for model selection. All analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and a two-sided P value of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. No assumptions were made for missing data.

Results

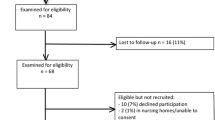

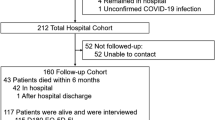

From November 6, 2013 to March 28, 2015, each site screened patients for a 4-month period. Of 373 eligible patients, 262 (70.2%) ICU survivors were enrolled (Fig. 2). In total, there were 175 (67%) men and the mean age was 59 ± 16 years. Seventy patients were aged over 70 years old. The most frequent primary diagnosis was cardiovascular (cardiogenic shock, ischaemia, arrhythmia, cardiac surgery), and there were few comorbidities (Table 2). Of the entire cohort, 107 (42%) were working or studying prior to the critical illness, while 92 (35%) were retired, 53 (20%) were not working and 10 (4%) were at home in an unpaid capacity.

Table 2 shows the baseline demographic data for patients enrolled in the study, comparing patients dichotomised using the WHODAS 2.0 (12-level) to groups with moderate to severe disability, N = 65 (25%), and with none or mild disability, N = 197 (75%), at 6 months after ICU. There were no differences at baseline between patients with and without a moderate to severe disability for age, gender, diagnosis, comorbidities or severity of illness (Table 2).

Hospital outcomes

The total median [IQR] length of stay in ICU and hospital was 1 week [6.7 days (4.2–10.9)] and 3 weeks [22.8 days (14.0–45.0)] respectively. There was no difference between ICU or hospital length of stay for patients with or without moderate to severe disability at 6 months; however, patients with none or mild disability were more likely to be discharged to home (Table 3).

Patient-reported outcomes at 6 months

Function and disability (WHODAS 2.0, 12-level)

In this cohort, 25% of patients reported no disability (WHODAS score 0–4%), 50% reported mild disability (WHODAS score 5–24%) and 25% reported moderate to severe disability (WHODAS score 25–95%). No patients reported complete disability (WHODAS score 96–100%). A history of depression or anxiety, being separated or divorced and discharge to another hospital or rehabilitation facility after the primary hospital admission were more common amongst patients with moderate to severe disability (Tables 2, 3). After multivariable analysis, predictors of moderate to severe disability included a history of anxiety and/or depression, being separated or divorced, longer duration of mechanical ventilation and not being discharged to home from the acute hospital (Table 4). A sensitivity analysis was conducted analysing the WHODAS 2.0 score with a dichotomy of no disability (score 0–4%) versus any disability (5–100%) to determine if this altered the outcomes and predictors of disability (eTables 1, 2).

Health-related quality of life (EQ5D-5L)

For the whole cohort, health-related quality of life was worse at 6 months after critical illness compared to the month prior to the illness as retrospectively recalled (utility score mean 0.8 ± 0.3 versus 0.7 ± 0.3 respectively, P = 0.025). Patients with a moderate to severe disability had a significant decrease in health status in all five domains of the EQ5D-5L compared to patients with no disability at 6 months (Table 3). In patients with a moderate to severe disability, the reduction in health status was greatest in the domains of mobility, personal care and usual activities.

Cognitive function (TICS)

Of the included patients, 225 completed the TICS to assess cognitive function. Of these, 218 (97%) were unimpaired, 5 (2%) were mildly impaired and 2 (0.7%) were severely impaired. There was no difference in cognitive function for survivors with or without a moderate to severe disability (Table 3).

Depression and anxiety (HADS)

Of the cohort, 238 completed the HADS. Clinically significant depression and anxiety were reported prior to the critical illness in 45 (17%) (Table 2). At 6 months after ICU, anxiety was reported in 49 (21%), depression in 41 (17%) and depression and/or anxiety in 53 (22%) survivors. Of the patients who reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depression at 6 months after ICU, one-third had pre-existing anxiety or depression. Patients with a moderate to severe disability reported significantly greater anxiety and depression symptoms than patients with none or mild disability (Table 3).

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Overall, the IES-R scores were indicative of potential PTSD in 22 of 231 (8%) patients who responded at 6 months after ICU. Patients with a moderate to severe disability were more likely to report PTSD symptoms than patients with none or mild disability (Table 3).

Return to work or usual activities

There were 107 people working or studying prior to admission to ICU. At 6 months after ICU, 64 (60%) had not returned to work or studies because of their health (Table 3). There was a significant difference in the number of patients who reported being unemployed as a result of their health with a moderate to severe disability compared to none or mild disability (Table 3).

Discussion

Key findings

In this study, the incidence of mild disability was 50% and that of moderate to severe disability was 25%. The most significant risk factors identified for moderate to severe disability were prior history of anxiety or depression, separation or divorce, a longer duration of mechanical ventilation and discharge to another hospital or rehabilitation facility rather than to home. Disability was identified in patients with a diverse range of diseases, and the heterogeneity of the included patients improves the generalisability of the conclusions. A key finding from this study was that the patient-reported outcome of disability using the WHODAS 2.0 in an ICU population was associated with a reduction in health-related quality of life and increased anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress. Notable factors that were not associated with disability include age, severity of illness, comorbidities, length of ICU or hospital stay and cognitive decline.

Measuring the burden of critical illness is a complex task, made particularly difficult by the heterogeneity of patient populations and the different trajectories of illness before and after the critical event [26, 27]. This study reported both disability and health status. Health-related quality of life or health status is an important subjective measure of well-being and is the most commonly reported long-term outcome after critical illness in Australia [28, 29]. Health status had deteriorated in each domain in this cohort and was significantly worse in survivors with ongoing disability. Measuring disability is a different outcome to health-related quality of life, and according to the WHO definition is important as it assesses the impact of health symptoms on the patient’s life in the domains of life role activities, social involvement, physical, psychological and cognitive well-being. The WHODAS 2.0 (12-level) is available in the public domain, can be used by self-report, proxy or by telephone and takes approximately 5 min to complete, is easy to use and score with excellent psychometric properties (as tested in other conditions). It should be considered for future use in ICU populations as a core outcome measure instead of individual tests of physical, psychological and cognitive function that are burdensome in terms of time and cost.

Comparison to other studies

Two important themes emerged as predictors of disability in this cohort, including (1) pre-existing psychological morbidity and (2) divorce and separation. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported pre-existing psychological morbidity as a risk factor for psychological dysfunction after ICU [22]. In a recent systematic review of 38 studies measuring depression after ICU using validated instruments, clinically important depressive symptoms occurred in approximately one-third of ICU survivors and were persistent through 12-month follow-up [22]. These authors reported both pre-ICU psychological morbidity and in-ICU psychological distress as risk factors for post-ICU depression. These findings support our data with regards to pre-ICU psychological morbidity and risk of depression or anxiety; however, we did not have a measure of in-hospital psychiatric distress and this would be an important area for future research in survivors of ICU. The biological pathway might involve a greater incidence of delirium in this group, which has certainly been associated with worse psychological and cognitive outcomes in other cohort studies [30, 31].

Marital status, and particularly divorce or separation, has not been previously identified as a strong predictor for disability in survivors of critical illness to the best of our knowledge. However, marital status has been identified as a predictor of functional outcome in survivors of cardiac surgery [32]. Compared to married patients, those who were divorced, separated or widowed had a 40% greater chance of dying or developing a functional disability in the first 2 years after cardiac surgery. The results of this study are similar, with a more than doubling of the odds of moderate to severe disability in patients who were separated or divorced. Characterising the association between marital status and disability after ICU may be useful for counseling patients and their families, and identifying at-risk groups that may benefit from targeted interventions aimed at improving recovery.

Studies investigating the long-term recovery of critically ill patients have consistently identified age and comorbidities as influencing functional outcome [33,34,35]. In our cohort, age was not associated with disability and this may be as a result of international differences in the admission criteria and selection of patients admitted to ICU. Similarly, invasive organ support in patients with severe existing comorbidity may have been limited in the ICU because of concerns about futility. In either case, selection bias is likely to have influenced the characteristics of our study cohort such that very old or severely unwell patients may not have survived to 6 months.

We found that strikingly few survivors screened positive for cognitive dysfunction, noting that the study excluded patients with known acute neurological injury. While the outcome measure we used was validated for use with telephone follow-up and for screening for dementia [21] and used with success in an older cohort after severe sepsis [36], its use has since been criticized in patients with acute respiratory failure [37] and may not be sensitive in this group of patients. Understanding whether this is an artefact of measurement, or represents a true difference in cognitive impairment stemming from differences in Australian ICU practice, is of potential broad significance.

Implications for clinical practice

Few interventions have been identified that improve long-term outcomes in ICU survivors, and the ability to follow up patients after ICU discharge has been challenging [3, 38]. The WHODAS 2.0 (12-level) should be considered by ICU clinicians and researchers as a preferred tool to measure disability and functioning. It is available in the public domain, can be used by self-report, proxy or telephone and takes approximately 5 min to complete. Future research should focus on developing and testing interventions that reduce disability and improve the ability of survivors to return to work and usual activities. There was a strong association between patients who were discharged to home and functional recovery. Alternately, patients who were discharged to rehabilitation facilities or other acute care centres after critical illness had increased disability at 6 months and may require additional resources to continue to improve, including links with primary care practitioners to address ongoing problems [39].

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths to our study. This was a multicentre cohort study, which included a mix of both public and private patients, increasing the external validity of the results. We used trained, centrally located, blinded outcome assessors to minimise bias. We included outcome assessments based on the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning to report on function, disability and participation, as well as health-related quality of life. The use of multiple outcome measures allows us to describe post-intensive care syndrome in Australian survivors of critical illness and compare this to international cohorts [2].

There are several limitations to this study. First, there were a large number of eligible patients who declined participation in the study or were non-responders and for whom we have no measure of the quality of their survival and for ethical reasons were unable to report their baseline characteristics. Second, the measures of comorbidities used may not be optimal to stratify patients for ongoing disability. Previous studies of ICU survivors have used other measures of comorbidities that may be more sensitive in this population, including the Functional Comorbidity Index [40]. Third, there was no measure of pre-existing disability or function; therefore, we did not measure the change in disability for our cohort as we did the change in health-related quality of life. Health-related quality of life prior to ICU admission was reported at 6 months after the critical illness and this method of determination may result in recall bias. Fourth, there is no information about the trajectory of the patients’ recovery as we measured function at 6 months only. Finally, we dichotomised the WHODAS II score according to a previously validated surgical population which may underestimate the amount of mild disability resulting from an ICU stay [20]. This needs further evaluation in large ICU cohorts.

Conclusion

Disability measured using patient-reported outcomes was prevalent at 6 months after critical illness in survivors and was associated with both reduced health-related quality of life and poor return to work due to result of health. Predictors of disability included a prior history of anxiety or depression, separation or divorce, a longer duration of mechanical ventilation and discharge to another hospital or rehabilitation facility rather than to home. Disability, measured using the WHODAS 2.0 (12-level), is an important outcome following critical illness and should be considered in a core outcome set for ICU research. Future research should focus on developing and testing interventions that reduce disability.

Change history

15 September 2017

In the Results section, under the subheading “Return to work or usual activities”, the second sentence should read.

References

Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R (2014) Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in ANZ, 2000–2012. JAMA 311:1308–1316

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, Zawistowski C, Bemis-Dougherty A, Berney SC, Bienvenu OJ, Brady SL, Brodsky MB, Denehy L, Elliott D, Flatley C, Harabin AL, Jones C, Louis D, Meltzer W, Muldoon SR, Palmer JB, Perme C, Robinson M, Schmidt DM, Scruth E, Spill GR, Storey CP, Render M, Votto J, Harvey MA (2012) Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 40:502–509

Hodgson C, Cuthbertson BH (2016) Improving outcomes after critical illness: harder than we thought! Intensive Care Med 42:1772–1774

Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Kudlow P, Cook D, Slutsky AS, Cheung AM (2011) Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Eng J Med 364:1293–1304

Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, Petersen C, Holve E, Segal CD, Franklin PD (2016) Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff 35:575–582

Lim WC, Black N, Lamping D, Rowan K, Mays N (2016) Conceptualizing and measuring health-related quality of life in critical care. J Crit Care 31:183–193

World Health Organization (2001) ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. WHO, Geneva

Iwashyna TJ (2010) Survivorship will be the defining challenge of critical care in the 21st century. Ann Intern Med 153:204–205

Leonardi M, Bickenbach J, Ustun TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S (2006) The definition of disability: what is in a name? Lancet 368:1219–1221

Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J, Saxena S, von Korff M, Pull C (2010) Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ 88:815–823

Carlozzi NE, Kratz AL, Downing NR, Goodnight S, Miner JA, Migliore N, Paulsen JS (2015) Validity of the 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) in individuals with Huntington disease (HD). Qual Life Res 24:1963–1971

Cheung MK, Hung AT, Poon PK, Fong DY, Li LS, Chow ES, Qiu ZY, Liou TH (2015) Validation of the World Health Organization Assessment Schedule II Chinese Traditional Version (WHODAS II CT) in persons with disabilities and chronic illnesses for Chinese population. Disabil Rehabil 37:1902–1907

Marx BP, Wolf EJ, Cornette MM, Schnurr PP, Rosen MI, Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Speroff T (2015) Using the WHODAS 2.0 to assess functioning among veterans seeking compensation for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv 66:1312–1317

Schlote A, Richter M, Wunderlich MT, Poppendick U, Moller C, Schwelm K, Wallesch CW (2009) WHODAS II with people after stroke and their relatives. Disabil Rehabil 31:855–864

Soberg HL, Finset A, Roise O, Bautz-Holter E (2012) The trajectory of physical and mental health from injury to 5 years after multiple trauma: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93:765–774

Hodgson C, Young M, Gabbe B, Higgins A, Iwashyna J, Myles P, Ponsford J, Pilcher D, Kulkarni J, Murray L, Bucknall T, Udy A, Cooper DJ (2016) Recovery after ICU in Australia: interim results of disability and cognitive dysfunction in survivors at 6 months. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193:A1180–A1180

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2007) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370:1453–1457

Knaus W, Draper E, Wagner D, Zimmerman J (1985) APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 13:818–829

Shulman MA, Myles PS, Chan MT, McIlroy DR, Wallace S, Ponsford J (2015) Measurement of disability-free survival after surgery. Anesthesiology 122:524–536

Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, Maclennan G, Vale L (2010) Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care 14:R6

Lacruz M, Emeny R, Bickel H, Linkohr B, Ladwig K (2013) Feasibility, internal consistency and covariates of TICS-m (telephone interview for cognitive status-modified) in a population-based sample: findings from the KORA-Age study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 28:971–978

Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, Huang M, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Turnbull AE, Needham DM (2016) Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 44:1744–1753

Bienvenu OJ, Williams JB, Yang A, Hopkins RO, Needham DM (2013) Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of acute lung injury: evaluating the impact of event scale-revised. Chest 144:24–31

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–381

Andrews G, Kemp A, Sunderland M, Von Korff M, Ustun TB (2009) Normative data for the 12 item WHO disability assessment schedule 2.0. PLoS One 4:e8343

Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, Hopkins RO, Rice TW, Bienvenu OJ, Azoulay E (2016) Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med 42:725–738

Needham DM, Dowdy DW, Mendez-Tellez PA, Herridge MS, Pronovost PJ (2005) Studying outcomes of intensive care unit survivors: measuring exposures and outcomes. Intensive Care Med 31:1153–1160

Hodgson CL, Watts NR, Iwashyna TJ (2016) Long-term outcomes after critical illness relevant to randomized clinical trials. In: Vincent J-L (ed) Annual update in intensive care and emergency medicine 2016. Springer, USA

Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Dennison CR, Mendez-Tellez PA, Herridge MS, Guallar E, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM (2006) Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 32:1115–1124

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK, Moons KG, Geevarghese SK, Canonico A, Hopkins RO, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW (2013) Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 369:1306–1316

Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Brummel NE, Thompson JL, Hughes CG, Pun BT, Vasilevskis EE, Morandi A, Shintani AK, Hopkins RO, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW (2014) Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2:369–379

Neuman MD, Werner RM (2016) Marital status and postoperative functional recovery. JAMA Surg 151:194–196

Herridge MS, Chu LM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Chan L, Thomas C, Friedrich JO, Mehta S, Lamontagne F, Levasseur M, Ferguson ND, Adhikari NK, Rudkowski JC, Meggison H, Skrobik Y, Flannery J, Bayley M, Batt J, Santos CD, Abbey SE, Tan A, Lo V, Mathur S, Parotto M, Morris D, Flockhart L, Fan E, Lee CM, Wilcox ME, Ayas N, Choong K, Fowler R, Scales DC, Sinuff T, Cuthbertson BH, Rose L, Robles P, Burns S, Cypel M, Singer L, Chaparro C, Chow CW, Keshavjee S, Brochard L, Hebert P, Slutsky AS, Marshall JC, Cook D, Cameron JI (2016) The RECOVER Program: disability risk groups and 1-year outcome after 7 or more days of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 194:831–844

Puthucheary ZA, Denehy L (2015) Exercise interventions in critical illness survivors: understanding inclusion and stratification criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191:1464–1467

Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM (2012) Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:1070–1077

Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM (2010) Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA 304:1787–1794

Pfoh ER, Chan KS, Dinglas VD, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morris PE, Hough CL, Mendez-Tellez PA, Ely EW, Huang M, Needham DM, Hopkins RO (2015) Cognitive screening among acute respiratory failure survivors: a cross-sectional evaluation of the Mini-Mental State Examination. Crit Care 19:220

Tipping CJ, Harrold M, Holland A, Romero L, Nisbet T, Hodgson CL (2017) The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 43(2):171–183. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4612-0

Schmidt K, Worrack S, Von Korff M, Davydow D, Brunkhorst F, Ehlert U, Pausch C, Mehlhorn J, Schneider N, Scherag A, Freytag A, Reinhart K, Wensing M, Gensichen J (2016) Effect of a primary care management intervention on mental health-related quality of life among survivors of sepsis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315:2703–2711

Fan E, Gifford JM, Chandolu S, Colantuoni E, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM (2012) The functional comorbidity index had high inter-rater reliability in patients with acute lung injury. BMC Anesthesiol 12:21

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the site co-ordinators at each of our hospitals, including Glenn Eastwood, Pauline Galt, Gabby Hanlon and Donna McCallum. We would like to acknowledge the support of Kathleen Collins and financial support from Monash Partners Academic Health Science Centre, Melbourne, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Take-home message: Moderate to severe disability measured using the World Health Organisation’s Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 was prevalent in 25% of survivors at 6 months after ICU admission, and was more common in people who were separated or divorced, had a history of anxiety or depression and who were mechanically ventilated for a longer period of time. Disability was associated with reduced health-related quality of life, especially in the domains of mobility, usual activities and pain.

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4937-3.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hodgson, C.L., Udy, A.A., Bailey, M. et al. The impact of disability in survivors of critical illness. Intensive Care Med 43, 992–1001 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4830-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4830-0