Abstract

Purpose

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) in critically ill patients has a high incidence despite prophylactic measures. This fact could be related to an inappropriate use of these measures due to the absence of specific VTE risk scores. To assess the current situation in Spain, we have performed a cross-sectional study, analyzing if the prophylactic measures were appropriate to the patients’ VTE risk.

Methods

Through an electronic questionnaire, we carried out a single day point prevalence study on the VTE prophylactic measures used in several critical care units in Spain. We performed a risk stratification for VTE in three groups: low, moderate–high, and very high risk. The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines were used to determine if the patients were receiving the recommended prophylaxis.

Results

A total of 777 patients were included; 62 % medical, 30 % surgical, and 7 % major trauma patients. The median number of the risk factors for VTE was four. According to the proposed VTE risk score, only 2 % of the patients were at low risk, whereas 83 % were at very high risk. Sixty-three percent of patients received pharmacological prophylaxis, 12 % mechanical prophylaxis, 6 % combined prophylaxis, and 19 % did not receive any prophylactic measure. According to criteria suggested by the guidelines, 23 % of medical, 71 % of surgical, and 70 % of major trauma patients received an inappropriate prophylaxis.

Conclusions

Most critically ill patients are at high or very high risk of VTE, but there is a low rate of appropriate prophylaxis. The efforts to improve the identification of patients at risk, and the implementation of appropriate prevention protocols should be enhanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is currently the main preventable complication in hospitalized patients [1]. Although its incidence has decreased from 30–60 to 5–10 % [2–4] after the introduction of routine VTE prophylactic measures, it remains a common clinical entity in critically ill patients.

For over 20 years, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) has been regularly publishing guidance on VTE prophylaxis [5]. However, the first guidelines including specific recommendations for critically ill patients are relatively recent [6]. In general, these recommendations include the use of pharmacological prophylaxis as the main preventive measure, leaving mechanical prophylaxis for patients at high risk of bleeding.

The appropriate prescription of thromboprophylaxis can improve VTE prevention and has been proposed as a cost-effective strategy [7]. It has also been considered as an indicator of both health care quality and patient safety [8]. However, recent epidemiological studies show a poor implementation of the prophylactic measures proposed in the guidelines [9–12].

Little data regarding compliance with VTE prophylaxis recommendations in critically ill patients are available in Spain. The purpose of this study was to describe the VTE prophylactic measures actually used, as well as to determine if their use was appropriate in accordance with ACCP 2012 guidelines [13, 14].

Methods

The PROF-ETEV study was a multicenter, epidemiological, and cross-sectional study performed in patients admitted to different critical care units in Spain. A coordination committee (“Appendix”) was responsible for the selection of the most relevant units in the country, which were sent the study protocol. The subsequent electronic questionnaire (e-CRF) was sent to those who chose to participate. This e-CRF format was considered appropriate to obtain the required data, as it had been previously used in prior epidemiological studies [12, 15].

The patients’ anonymity was strictly maintained in e-CRF and in the corresponding database. The Ethical Committee of Clinical Research of Gregorio Marañón University Hospital reviewed and approved the study protocol in June 2013 and waived the need for informed consent. Finally, on 26 June 2013 a single day point prevalence study on actual VTE prophylactic measures was carried out.

Inclusion criteria

Patients over 18 years old admitted to units at 10:00 a.m. on the survey day.

Exclusion criteria

Patients receiving any type of anticoagulation or with a diagnosis of VTE disease.

Collected data

-

1.

Units’ data: number of beds, number of patients admitted with systemic anticoagulation or VTE disease, as well as the use of some VTE prophylaxis protocol within the unit.

-

2.

Patients’ data: epidemiologic data, reason for admission (medical, surgical, or major trauma pathologies), specific data related to their stay in the unit (disease severity, mechanical ventilation, vasopressor drugs), risk factors for VTE, and risk factors for bleeding [13, 14, 16–23], as well as the VTE prophylactic measures actually used: pharmacological [low dose unfractionated heparin (LDUH), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and others]; mechanical [intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) and graduated compression stocking (GCS)], and combined (pharmacological and mechanical measures simultaneously).

Risk stratification for VTE

In the absence of VTE risk scores for critically ill patients, we performed a risk stratification based on the algorithm proposed by Laport and Mismetti [16], to which the modified risk assessment proposed by Caprini [19, 20] was associated, as it contains a very high risk group (DVT rate 40–80 %), wherein many of the critically ill patients could be included [2]. Thus, three groups of patients were established: low risk, moderate–high risk (receiving the same type according to ACCP 2012 guidelines), and very high risk patients (Table 1).

Risk of bleeding

The patients were considered at high risk of bleeding if they had either multiple risk factors (bleeding risk score >7), or one of the three risk factors most strongly associated with bleeding according to the IMPROVE study [13, 21]: active gastroduodenal ulcer, bleeding within the 3 months prior to admission, or platelet count no greater than 50,000 mm3.

Contraindications to pharmacological prophylaxis

The following clinical situations were considered as contraindications: active gastroduodenal ulcer, bleeding on admission, intracranial hemorrhage, major surgery, major trauma, platelet count no greater than 50,000 mm3, and severe coagulopathy (aPTT ratio or INR >2).

Contraindications to mechanical prophylaxis

The following clinical situations were considered as contraindications: dermatitis, ulcers, edema, and severe peripheral vascular disease.

Adequate prophylaxis consideration

This was based on ACCP 2012 recommendations [13, 14] (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

As a result of the characteristics of the study only a descriptive analysis was performed. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to analyze if quantitative variables were adjusted to normal, in which case they were expressed as a mean (standard deviation), and otherwise expressed as a median (interquartile range). Analysis of qualitative variables was expressed as a number and percentage.

IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 21 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Seventy-three out of the 83 critical care units initially selected (88 %) participated in the study. Most of the units were medical-surgical (86 %) and belonged to level III hospitals (72 %). Only 35 % (26 units) used a VTE prophylaxis protocol and 11 % (8 units) reported the use of a VTE risk score.

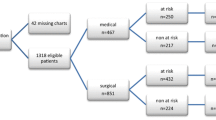

A total of 972 patients were admitted on the survey day (median 12, IQR 6–17). One hundred and ninety-five patients (20 %) were excluded: 174 (17.7 %) were receiving anticoagulation and 23 (2.3 %) had been diagnosed with VTE disease.

Seven hundred and seventy-seven patients were finally included; their characteristics are summarized in Table 2. It should be noted that 62 % of patients (481/777) presented some medical pathology at admission; 23.6 % (183/777) were receiving vasopressor therapy; 43 % (333/777) required invasive mechanical ventilation; and 6.3 % (43/777) required non-invasive mechanical ventilation. Median length of unit stay up to the survey date was 5 days (IQR 2–12).

Risk factors for VTE, before admission and during hospitalisation, are shown in Table 3. Patients exhibited a median of four risk factors for thrombosis (IQR 3–6). According to the VTE risk score proposed, 16 patients (2.1 %) were at low risk, 115 (14.8 %) at moderate–high risk, and 646 (83.1 %) at very high risk, including 362 (46 %) of medical patients (Table 3).

Two hundred patients (26 %) were considered at high risk of bleeding and 214 patients (27.5 %) had pharmacological prophylaxis contraindications, mainly due to recent major surgery, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathy (see the electronic supplementary material).

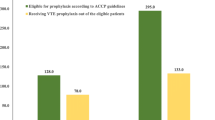

Figure 1 summarizes the VTE prophylactic measures actually used. Eighty-one percent of the patients (627/777) were receiving some prophylactic measure: 78.6 % (378/481) of the medical patients, 84.3 % (199/236) of the surgical patients, and 83.3 % (50/60) of the major trauma patients. Time elapsed before the application of any prophylactic measure was 1 day (IQR 0–1), although in 25 % of major trauma patients prophylaxis was delayed until the third day (median 1 day, IQR 1–3).

Pharmacological prophylaxis was the most common prophylactic measure, as it was used in 78.3 % (491/627) of the patients. Overall, pharmacological prophylaxis was administered to 92.5 % (521/563) of the potentially suitable patients. LMWH was almost the only pharmacological agent used (97 %, 477/491). Time taken until pharmacological prophylaxis application was 1 day (IQR 1–3), although in 25 % of patients with major trauma it was delayed until the seventh day (median 3 days, IQR 1–7). Enoxaparin (76.8 %) and bemiparin (18.4 %) were the most common forms of LMWH used.

LMWH dose was adjusted by anti-Xa factor level in only four patients (0.8 %), although a different dose than the usual was administered in 78 patients (15 %), mainly as a result of severe renal failure (6.6 %), high risk of bleeding (2.7 %), obesity (2.9 %), and high risk of VTE (2.9 %). Up to the survey day only six patients with pharmacological prophylaxis had suffered bleeding complications (1.1 %). There was a suspicion of heparin-induced thrombopenia in 15 patients (2.8 %), although it was only confirmed in two cases (0.4 %).

Mechanical prophylaxis was used in 15 % of all patients (94/627), but only in 39 % (82/214) of the potentially suitable patients, as a result of pharmacological prophylaxis contraindications. The most common form of mechanical prophylaxis was IPC, used in 77 % of patients (105/136). Some contraindication for mechanical devices was reported in 4.6 % of the patients (36/777), mainly as a result of severe injury in lower extremities or peripheral vascular disease.

Combined prophylaxis was used in 6.7 % of patients (42/627), mainly in major trauma patients (14 %) and surgical patients (10 %). The most common combination was an IPC device with an LMWH (80.5 %). In patients at very high risk of VTE only 9.5 % (27/284) received this prophylactic modality, excluding medical patients, as its use in such patients is not currently recommended.

One hundred and fifty patients (19.3 %) did not receive any prophylactic measure. The absence of prophylaxis was more frequent in medical patients (21.4 %) than in surgical (16.7 %) or major trauma (16.7 %) patients. Note that 75 % of patients without prophylaxis (117/150) had pharmacological prophylaxis contraindications.

According to the proposed VTE risk stratification (Table 1) and the ACCP 2012 recommendations, 23.3 % (112/481) of medical patients, 71.3 % (168/236) of surgical patients, and 70 % (42/60) of major trauma patients were being administered an inadequate prophylaxis.

Discussion

The PROF-ETEV study is the first national record of VTE prophylactic measures used in critically ill patients carried out in Spain. It is also an attempt to evaluate the appropriateness of VTE prophylaxis prescriptions according to the guidelines in a wide variety of critical care units.

In agreement with previous studies [9–12] we found a poor guideline adherence. Our data show that VTE prophylactic measures were improperly used in a significant number of patients (42 %). The most serious failure to comply was observed in 19 % of patients that did not receive any prophylactic measure at all. There was a poor use of mechanical prophylaxis, only used in a third of the patients with indication, as well as an infrequent use of combined prophylaxis, used only in 11 % of the patients at very high risk of VTE.

Only 36 % of the units reported the use of some VTE prophylaxis protocol, far from the ACCP recommendations [14, 15] and the compliance of quality indicators proposed by our national scientific society [8]. In the absence of VTE risk scores for critically ill patients we have proposed a risk stratification (Table 1), including risk factors for VTE as well as specific clinical situations in critically ill patients [24], in order to improve the selection of the most suitable prophylactic measure. According to this score, a large number of patients would be at very high risk of VTE.

With reference to our results, we conducted a review of the literature on this topic.

Prophylaxis for VTE in critically ill patients

The ACCP 2012 guidelines suggest the use of prophylaxis in the critical patient (grade 2C). Although there are few clinical trials in critically ill patients, which impedes high levels of evidence and recommendation, it is most unlikely that new clinical trials will be developed in this respect. Instead, systematic reviews and meta-analysis could be a useful way to approach this subject. A study by Alhazzani et al. [25], including 7,226 critically ill patients, showed the benefits of pharmacological prophylaxis versus the absence of any prophylaxis in DVT (RR 0.51, 95 % CI 0.41–0.63) and PE (RR 0.52, 95 % CI 0.28–0.97). Ho and Tan [26], in a study involving 16,164 patients using mechanical prophylaxis due to pharmacological prophylaxis contraindication, showed a reduction in DVT (RR 0.43, 95 % CI 0.36–0.52) and PE (RR 0.48, 95 % CI 0.33–0.69). Finally, in a record of 175,665 critically ill patients of 134 ICUs in Australia and New Zealand, prophylaxis omission on the first day of admission was associated with a mortality increase (OR 1.22, 95 % CI 1.15–1.30) [27].

Pharmacological prophylaxis in critically ill patients

Following the ACCP recommendations (grade 2C), pharmacological prophylaxis with heparin was the most common prophylactic measure. In Spain, as in other European countries [9, 12], LMWH was almost the only drug used. The variability in the use of different heparins reflects the lack of evidence with regards to a greater benefit in medical patients [3, 14, 28], although there seems to be a greater benefit in using LMWH in very high risk surgical and major trauma patients [15]. In this respect, the meta-analysis published by Alhazzani et al. [25] and Kanaan et al. [29] showed a reduction in VTE disease in patients treated with LMWH versus LDUH.

The LMWH mostly used was enoxaparin. There are no clinical trials showing superiority of an LMWH in particular [30] and, therefore, there are no recommendations to this regard [14, 15]. The standard dose of LMWH was the most widely used. Although adjusted in only four patients according to factor anti-Xa levels, in a significant percentage of patients (15 %) a different dose was used. This was dependent on specific clinical features such as renal failure, obesity, and a high risk of VTE or bleeding. Currently, guidelines do not recommend routine use of factor anti-Xa levels to adjust LMWH dose [14, 15, 31], although controversy still exists [32–34]. However, the administration of repeated doses of enoxaparin in patients with renal function impairment could produce accumulation of the drug, and a decrease in dose would be justified [31]. In our study the LMWH dose was adjusted only in 30 % of patients with renal failure.

Mechanical prophylaxis in critically ill patients

In patients with pharmacological prophylaxis contraindications, the ACCP guidelines suggest (grade 2C) the use of mechanical prophylaxis [14, 15]. A quarter of the patients analyzed had a high risk of bleeding and/or other pharmacological prophylaxis contraindication. However, only a small percentage of these patients received mechanical prophylaxis [35].

In Spain, the most common form of mechanical prophylaxis was the IPC. A recent randomized trial specifically designed to evaluate the potential benefit of GCS or IPC in ICU patients with a high risk of bleeding did not find differences between these mechanical devices [36]. A recently published meta-analysis (RR 0.43, 95 % CI 0.36–0.52) [25] and a prospective cohort study (HR 0.45, 95 % CI 0.22–0.95) [37], have shown the effectiveness of IPC, but not of GCS, to reduce DVT in medical or surgical critically ill patients. Nevertheless, in certain groups of patients, such as surgical and major trauma patients with very high risk of VTE, there seems to be a greater benefit with IPC, which is, therefore, suggested by the guidelines [15]. Lastly, we refer to the CLOTS-3 trial [38], a multicenter, randomized study, whose objective was to assess the efficacy of an IPC device in immobile patients with acute stroke, showing a reduction of DVT and mortality.

Combined prophylaxis in critically ill patients

Guidelines suggest the use of combined prophylaxis in surgical and major trauma critically ill patients at very high risk of VTE (grade 2C) [14]. In the absence of specific clinical trials in this respect, the meta-analyses published by Barrera et al. [39] and Kakkos et al. [40] have shown favorable results to this effect. Results of the CLOTS-3 study [38], where around a third of the patients with IPC had associated pharmacological prophylaxis, lead us to believe that combined prophylaxis could also be effective in certain medical patients at very high risk of VTE. Despite this, in our study only a very small percentage of the patients received combined prophylaxis.

Our results are similar to those from others studies conducted in different countries [9–12]. It seems that, regardless of the local or individual circumstances in each country, improper use of VTE prophylaxis measures in critically ill patients is a widespread problem. We believe this could be partly due to the complexity of the guidelines, caused by the great variety of pathologies present in critically ill patients. We propose a simplified algorithm of VTE prophylaxis (Fig. 2) based on a current literature review, guidelines, and results provided by our study. This may facilitate the implementation of prophylactic measures, thus improving compliance.

Simplified algorithm of the VTE prophylaxis in critically ill patients. IPC intermittent pneumatic compression, LMWH low molecular weight heparin. 1 Every critically ill patient requires prophylaxis. 2 Every surgical or major trauma patient is considered at very high risk of VTE. 3 Daily assessment of the situation to adapt VTE prophylaxis

Our study has several limitations. Despite the high number of units and patients taking part, the results should not be generalized to all units in the country. The cross-sectional design of the study only allows the assessment of the compliance of prophylactic measures until the survey day. The stratification of the patients’ VTE risk, as well as the considerations related to the adequacy of the actual prophylaxis used, based on ACCP 2012 guidelines, derives from the present study’s coordinating committee and is, therefore, subject to discussion.

Conclusions

The PROF-ETEV study emphasizes that most critically ill patients are at high or very high risk of VTE, but there is a low rate of appropriate prophylaxis. The efforts to improve the identification of patients at risk as well as the implementation of appropriate prevention protocols should be enhanced.

References

Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, Arcelus JI, Bergqvist D, Brecht JG, Geer IA, Heit JA, Hutchinson JL, Kakkar AK, Mottier D, Oger E, Samama MM, Spannagl M, VTE Impact Assessment Group in Europe (VITAE) (2007) Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost 98:756–764

Attia J, Ray JG, Cook DJ, Douketis J, Ginsberg JS, Geerts WH (2001) Deep vein thrombosis and its prevention in critically ill adults. Arch Intern Med 161:1268–1279

PROTECT Investigators for the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Cook DD, Meade M, Guyatt G, Heels-Ansdell D, Warkentin TE, Zytaruk N, Crowther M, Geerts W, Cooper DJ, Vallance S, Qushmaq I, Rocha M, Berwanger O, Vlahakis NE (2011) Dalteparin versus unfractionated heparin in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 364:1305–1314. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1014475

Khouli H, Shapiro J, Pham VP, Arfaei A, Esan O, Jean R, Homel P (2006) Efficacy of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in the medical intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med 21:352–358

Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Levine MN, Salzman EW, Wheeler HB (1992) Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 102:391S–407S

Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Bergqvist D, Lassen, Colwen CW, Ray J (2004) Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the seventh ACCP conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest 126:338S–400S

Sud S, Mittmann N, Cook DJ, Geerts W, Chan B, Dodek P, Gould MK, Guyatt G, Arabi Y, Fowler RA (2011) Screening and prevention of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients a decision analysis and economic evaluation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184:1289–1298. doi:10.1164/rccm.201106-1059OC

Quality indicators in critically ill patients (2011) Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias (SEMICYUC). ISBN:978-84-615-3670-2. http://www.semicyuc.org/sites/default/files/quality_indicators_update_2011.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2014

Lacherade JC, Cook D, Heyland D, Chrusch C, Brochard L, Brun-Buisson Ch; French and Canadian ICU Directors Groups (2003) Prevention of venous thromboembolism in critically ill medical patients: a Franco-Canadian cross-sectional study. J Crit Care 18:228–237

Tapson VF, Decousus H, Pini M, Chong BH, Froehlich JB, Monreal M, Spyropoulos AC, Merli GJ, Zotz RB, Bergmann JF, Pavanello R, Turpie AG, Nakamura M, Piovella F, Kakkar AK, Spencer FA, Fitzgerald G, Anderson FA Jr, IMPROVE investigators (2007) Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: findings from the International Medical Prevention Registry on venous thromboembolism. Chest 132:936–945

Robertson MS, Nichol AD, Higgins AM, Bailey MJ, Presneill JJ, Cooper DJ, Webb SA, McArthur C, Maclsaac CM, VTE Point Prevalence Investigators for the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group (2010) Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the critically ill: a point prevalence survey of current practice in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units. Crit Care Resusc 12:9–15

Schaden E, Metnitz PG, Pfanner G, Heil S, Pernerstorfer T, Perger P, Schoechl H, Fries D, Guetl M, Kozek-Langenecker S (2012) Coagulation day 2010: an Austrian survey on the routine of thromboprophylaxis in intensive care. Intensive Care Med 38:984–990. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2533-0

Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, Cushman M, Dentali F, Akl EA, Cook DJ, Belekian AA, Klein RC, Le H, Schulman S, Murad MH, American College of Chest Physicians (2012) Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 141(2 Suppl):e195S–226S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2296

Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, Karanicolas PJ, Arcelus JI, Heit JA, Samama CM, American College of Chest Physicians (2012) Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 141(2 Suppl):e227S–277S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2297

García-Olivares P, Guerrero JE, Tomey MJ, Hernangómez AM, Stanescu DO (2014) Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease in the critical patient: an assessment of clinical practice in the community of Madrid. Med Intensiva 38:347–355. doi:10.1016/j.medin.2013.07.005.Epub

Laporte S, Mismetti P (2010) Epidemiology of thrombotic risk factors: the difficulty in using clinical trials to develop a risk assessment model. Crit Care Med 38(2 Suppl):S10–17. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c9cc3b

Rocha AT, Paiva EF, Lichtenstein A, Milani R Jr, Cavalheiro-Filho C, Maffei FH (2007) Risk-assessment algorithm and recommendations for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical patients. Vasc Health Risk Manag 3:533–553

Mesgarpour B, Heidinger BH, Schwameis M, Kienbacher C, Walsh C, Schmitz S, Herkner H (2013) Safety of off-label erythropoiesis stimulating agents in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 39:1896–1908. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-3030-9.Epub

Caprini JA, Arcelus JI, Reyna JJ (2001) Effective risk stratification of surgical and nonsurgical patients for venous thromboembolic disease. Semin Hematol 38:12S–19S

Caprini JA (2005) Thrombosis risk assessment as a guide to quality patient care. Dis Mon 51:70–78

Decousus H, Tapson VF, Bergman JF, Chong BH, Froehlich JB, Kakkar AK, Merli GJ, Monreal M, Nakamura M, Pavanello R, Pini M, Piovella F, Spencer FA, Spyropoulos AC, Turpie AG, Zotz RB, Fitzgerald G, Anderson FA (2011) Factors at admission associated with bleeding risk in medical patients: findings from the IMPROVE investigators. Chest 139:69–79. doi:10.1378/chest.09-3081

Arnold DM, Donahoe L, Clarke FJ, Tkaczyk AJ, Heels-Ansdell D, Zytaruk N, Cook R, Webert KE, McDonald E, Cook DJ (2007) Bleeding during critical illness: a prospective cohort study using a new measurement tool. Clin Invest Med 30:E93–E102

Lauzier F, Arnold DM, Rabbat C, Heels-Ansdell D, Zarychanski R, Dodek P, Ashley BJ, Albert M, Khwaja K, Ostermann M, Skrobik Y, Fowler R, McIntyre L, Nates JL, Karachi T, Lopes RD, Zytaruk N, Finfer S, Crowther M, Cook D (2013) Risk factors and impact of major bleeding in critically ill patients receiving heparin thromboprophylaxis. Intensive Care Med 39:2135–2143. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-3044-3

Cook D, Crowther M, Meade M, Rabbat C, Griffith L, Schiff D, Geerts W, Guyatt G (2005) Deep venous thrombosis in medical-surgical critically ill patients: prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. Crit Care Med 33:1565–1571

Alhazzani W, Lim W, Jaeschke RZ, Murad MH, Cade J, Cook DJ (2013) Heparin thromboprophylaxis in medical-surgical critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care Med 41:2088–2098. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf104

Ho KM, Tan AJ (2013) Stratified meta-analysis of intermittent pneumatic compression to the lower limbs to prevent venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Circulation 128:1003–1020. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002690

Ho KM, Chavan S, Pilcher D (2011) Omission of early thromboprophylaxis and mortality in critically ill patients: a multicenter registry study. Chest 140:1436–1446. doi:10.1378/chest.11-1444

Cheng SS, Nordenholz K, Matero D, Pearlman N, McCarter M, Gajdos C, Hamiel C, Baer A, Luzier E, Tran ZV, Olson T, Queensland K, Lutz R, Wischmeyer P (2012) Standard subcutaneous dosing of unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical ICU patients leads to subtherapeutic factor Xa inhibition. Intensive Care Med 38:642–6488. doi:10.1007/s00134-011-2453-4.Epub

Kanaan AO, Silva MA, Donovan JL, Silva MA, Donovan JL, Roy T, AI-Homsi AS (2007) Meta-analysis of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medically ill patients. Clin Ther 28:2395–2405

Ribic Ch, Lim W, Cook D, Crowther M (2009) Low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis in medical-surgical critically ill patients: a systematic review. J Crit Care 24:197–205. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.11.002

Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, Olav Vandvik P, Fish J, Kovacs MJ, Svensson PJ, Veenstra DL, Crowther M, Guyatt GH, American College of Chest Physicians (2012) Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 141(2 Suppl):e152S–184S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2295

Dörffler-Melly J, de Jonge E, Pont AC, Meijers J, Vroom MB, Buoller HR, Levi M (2002) Bioavailability of subcutaneous low molecular-weight heparin to patients on vasopressors. Lancet 359:849–850

Rommers MK, van der Lely N, Egberts TC, van den Bemt PM (2006) Anti-Xa activity after subcutaneous administration of dalteparin in ICU patients with and without subcutaneous oedema: a pilot study. Crit Care 10:R93

Malinoski D, Jafari F, Ewing T, Ardary C, Conniff H, Baje M, Kong A, Lekawa ME, Dolich MO, Cinat ME, Barrios C, Hoyt DB (2010) Standard prophylactic enoxaparin dosing leads to inadequate anti-Xa levels and increased deep venous thrombosis rates in critically ill trauma and surgical patients. J Trauma 68:870–874. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d32271

Cook D, Arabi Y, Ferguson N, Heels-Ansdell D, Freitag A, McDonald E, Clarke F, Keenan S, Pagliarello G, Plaxton W, Herridge M, Karachi T, Vallance S, Cade J, Crozier T, da Alves S Silva, Costa Filho R, Brandao N, Watpool I, McArdle T, Hollinger G, Mandourah Y, Al-Hazmi M, Zytaruk N, Adhikari NK, PROTECT Research Coordinators, PROTECT Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group (2013) Physicians declining patient enrollment in a critical care trial: a case study in thromboprophylaxis. Intensive Care Med 39:2115–2125

Vignon P, Dequin PF, Renault A et al (2013) Intermittent pneumatic compression to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with high risk of bleeding hospitalized in intensive care units: the CIREA1 randomized trial. Intensive Care Med 39:872–880. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2814-2

Arabi YM, Khedr M, Dara SI, Dhar GS, Bhat SA, Tamim HM, Afesh LY (2013) Use of intermittent pneumatic compression and not graduated compression stockings is associated with lower incident VTE in critically ill patients: a multiple propensity scores adjusted analysis. Chest 144:152–159. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2028

CLOTS (Clots in Legs Or sTockings after Stroke) Trials Collaboration, Dennis M, Sandercock P, Reid J, Graham C, Forbes J, Murray G (2013) Effectiveness of intermittent pneumatic compression in reduction of risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients who have had a stroke (CLOTS 3): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 382:516–524. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61050-8

Barrera LM, Perel P, Ker K, Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Morales Uribe CH (2013) Thromboprophylaxis for trauma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008303.pub2

Kakkos SK, Caprini JA, Geroulakos G et al (2011) Can combined (mechanical and pharmacological) modalities prevent fatal VTE? Int Angiol 30:115–122

Conflicts of interest

Pablo Garcia Olivares and Jose Eugenio Guerrero Sanz have participated in several symposiums about venous thromboembolic disease in critically ill patients, organized by Covidien Spain S.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

For the PROF-ETEV study investigators.

The members of the PROF-ETEV study investigators are given in the “Appendix”.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Coordinating Committee PROF-ETEV study:

Pablo García-Olivares, Jose Eugenio Guerrero (Gregorio Marañón Universitary Hospital, Madrid), Pedro Galdos (Puerta de Hierro Universitary Hospital, Madrid), Demetrio Carriedo (León Universitary Hospital, León), Francisco Murillo (Virgen del Rocio Universitary Hospital, Seville), Antonio Rivera (San Agustin Hospital, Asturias).

PROF-ETEV investigators:

Enrique Pino (H Rio Tinto, Huelva), María Victoria Torres (H Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga), Azucena de la Campa (HU Valme, Sevilla), Francisco José Romero (H Jerez ASISA, Cádiz), Luis Jiménez (H Santa Isabel, Sevilla), Manuel Castellano (H Alto Guadalquivir, Jaen), Jose Luis García (H San Juan de Dios, Sevilla), Luisa Cantón (H Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla), Rebeca Olalla (H Parque San Antonio, Málaga), Ana María de la Torre (H Xanit Internacional, Málaga), Guillermo Quesada (HU Carlos Haya, Málaga), Fernando Barra (HU Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), Raquel Bustamante y Belén Jiménez (HU Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza), Eduardo Antón (H Manacor, Menorca), Jose Ignacio Ayestarán (HU Son Espases, Mallorca), María Ripoll (HG Fuerteventura, Las Palmas), Moises Sánchez (H Doctor Jose Molina Orosa, Lanzarote), Ana Bueno (HU Ciudad Real), Elena Yañez (HU Guadalajara), Victoria Merino (H Virgen de la Salud, Toledo), Jose Manuel Gutierrez (HU Albacete), Miriam Riesco y Miriam González (CAU León), Virginia Fraile (HU Rio Hortega, Valladolid), Mercedes Martín-Macho (CA Palencia), Sergio Ossa (HU Burgos), Antonia Vazquez (H del Mar-Parq de Salut Mar, Barcelona), Juan Carlos Ruiz (H Vall d´Hebron, Barcelona), Juan Carlos Villalba e Hipólito Pérez (H Germans Trias I Pujol, Barcelona), Rosa María Catalán (HG de Vic, Barcelona), Basilio Sánchez, Elena Gallego y Rocio Manzano (H San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres), Loro Vieites (H Infanta Cristina, Badajoz), Marcela Peruccioni y Juan Bonastre (HU la Fe, Valencia), Laura Galarza (HU Castellón), Laura Beliver (HU Doctor Peset, Valencia), Pablo Vidal (HU Ourense), David Mosquera (H Meixoeiro, Vigo), Eva Menor (HU Vigo), Jose Francisco Olea (H Lucus Augusti, Lugo), Rita Galeiras y Leticia Seoane (HU A Coruña), Jose Luis Monzón (H San Pedro, Logroño), Ana María Hernangómez, Dennis O Stanescu y Ana Lajara (HU Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), Amparo Carbonell, Susana Temprano y Emilio Alted (HU Doce de Octubre, Madrid), Ana Villasclaras y Susana García (HU Ramón y Cajal, Madrid), Miguel Angel González y Alberto Valverde (HU Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Federico Gordo (HU del Henares, Madrid), Nicolas Nin (HU de Torrejón), Cesar Pérez (Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid), Teresa Honrubia (HU Mostoles, Madrid), Santiago Yuste y Juan Carlos Figueira (HU La Paz), Alberto Rubio (HM Montepríncipe, Madrid), Joaquín Alvarez (HU Fuenlabrada, Madrid), Pedro Galdos (HU Puerta de Hierro, Madrid), María Isabel Moreno (H Infanta Cristina, Madrid), Ana de Pablo (HU Sureste, Madrid), Eduardo Palencia (HU Infanta Leonor, Madrid), Luis Córdoba (HM Sanchinarro, Madrid), Judit Iglesias (HU La Princesa, Madrid), Santiago Jose Villanueva y Francisco Leon (HC de Melilla), Jose Manuel Allegue y Luis Herrera (HU Santa Lucia, Murcia), Andrés Carrillo (HU Jose María Morales Meseguer, Murcia), Isabel Cremades (HU Reina Sofia, Murcia), Jose Raúl Arevalo (HU Cruces, Bilbao), Mercedes Zabarte (HU Donostia, San Sebastian), María Martínez y Belén García (HUC de Asturias, Oviedo), Gerardo Aguilar, Juan Vicente Llau, Gergana Gencheva y Francisco Javier Belda (HCU De Valencia).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-Olivares, P., Guerrero, J.E., Galdos, P. et al. PROF-ETEV study: prophylaxis of venous thromboembolic disease in critical care units in Spain. Intensive Care Med 40, 1698–1708 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3442-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3442-1