Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the psychological consequences among family members given the option to be present during the CPR of a relative, compared with those not routinely offered the option.

Methods

Prospective, cluster-randomized, controlled trial involving 15 prehospital emergency medical services units in France, comparing systematic offer for a relative to witness CPR with the traditional practice among 570 family members. Main outcome measure was 1-year assessment included proportion suffering post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression symptoms, and/or complicated grief.

Results

Among the 570 family members [intention to treat (ITT) population], 408 (72 %) were evaluated at 1 year. In the ITT population (N = 570), family members had PTSD-related symptoms significantly more frequently in the control group than in the intervention group [adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.1–3.0; P = 0.02] as did family members to whom physicians did not propose witnessing CPR [adjusted odds ratio, 1.7; 95 % CI 1.1–2.6; P = 0.02]. In the observed cases population (N = 408), the proportion of family members experiencing a major depressive episode was significantly higher in the control group (31 vs. 23 %; P = 0.02) and among family members to whom physicians did not propose the opportunity to witness CPR (31 vs. 24 %; P = 0.03). The presence of complicated grief was significantly greater in the control group (36 vs. 21 %; P = 0.005) and among family members to whom physicians did not propose the opportunity to witness resuscitation (37 vs. 23 %; P = 0.003).

Conclusions

At 1 year after the event, psychological benefits persist for those family members offered the possibility to witness the CPR of a relative in cardiac arrest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The grief caused by the loss of a family member can induce pathological responses: a depressive state, anxiety, post-traumatic stress syndrome, or complicated grief [1–5]. These morbid factors can be influenced by the circumstances of death and particularly by whether the family is offered the opportunity to witness the patient’s medical treatment [6, 7].

The concept of family presence during the cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) of a patient was introduced in the 1980s [8]. In 2010, the American Heart Association recommended that family members be present during resuscitation procedures without reference to studies providing a high standard of proof of benefit [9]. In spite of these recommendations, most health-care professionals are highly reluctant to permit families to witness resuscitation attempts [10, 11].

We published in 2013 results of a multicenter, randomized trial that demonstrated a significant short-term improvement on several psychological parameters when the health-care team offered the family the possibility to be present during CPR [12].

In this article, we report our 1-year prespecified assessment of psychological symptoms and grief following the offer (or absence thereof) for family to be present during CPR of a relative from our trial.

Patients and methods

Participant selection and study procedures

The PRESENCE trial design (a multicenter randomized controlled trial) has been previously reported [12]. Fifteen prehospital emergency medical services units (SAMU) in France participated in this study from November 2009 to October 2011. Five hundred and seventy adult family members of adult patients in cardiac arrest occurring at home were prospectively included. A medical team member systematically asked family members allocated to the intervention group if they wished to be present during the resuscitation, and those accepting were accompanied by a supporting emergency staff member who provided technical information on the resuscitation. A communication guide (see electronic supplementary material) was available in order to help introduce the relative to the resuscitation scene and, when required, to help with the announcement of the death. These recommendations were developed from published guidelines [6, 13, 14]. Family members allocated to the control group were not routinely given the option to be present during CPR. Two hundred and sixty-six family members were allocated to the intervention group (266 relatives, 100 % given the opportunity to witness resuscitation) and 304 (59 relatives, only 19 % given the opportunity to witness resuscitation) to the control group. The study was approved by the institutional review board (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-De-France 10).

Follow-up and psychological assessment of family members

At 1-year post-resuscitation, a trained psychologist, unaware of group allocation, asked enrolled relatives to answer a structured questionnaire by telephone. The interviewer asked relatives to complete the impact of event scale (IES), the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), the inventory of complicated grief (ICG), and the structured diagnosis of a major depressive episode (MINI) [15–18]. A relative was deemed unreachable after 15 calls went unanswered.

The IES and HADS scores were described in our main study [12]. Briefly, the IES score ranges from 0 (no PTSD-related symptoms) to 75 (severe PTSD-related symptoms). Presence of PTSD is defined by an IES score greater than 30. The HADS is made up of two subscales, one evaluating symptoms of anxiety (HADSA; seven items) and the other assessing symptoms of depression (HADSD; seven items) [16]. Subscale scores range from 0 (no distress) to 21 (maximum distress). HADS subscale scores above 10 indicate moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety or depression [7, 19].

The ICG score is a self-administered questionnaire designed to diagnose traumatic grief, based on the criteria developed by Prigerson [3]. This scale has been translated into French and validated by Bourgeois [20]. It is composed of 19 items representing symptoms of traumatic grief which appear within 2 weeks post-loss and last for more than 2 months. The aim of this test is to identify subjects at risk of complicated grief. Complicated grief is defined as a score greater than or equal to 25.

The MINI (DSM-IV) is a brief, structured, standardized diagnostic interview for the major axis I psychiatric disorders in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994). In this study, we evaluated survivors using module “A” (major depressive episode). It is used to formulate diagnoses based on the DSM-IV criteria. This instrument, which is widely used internationally, has been validated in French and compared to the structured clinical interview for DSM (SCID-P) and the composite international diagnostic interview for ICD-10 (CIDI). It is an interviewer-administered evaluation that can be used by researchers after a brief training session [18, 21].

Statistical analysis

The main analysis of the percentage of PTSD-related symptoms was based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (i.e., 570 randomized patients). For this main analysis, we considered participants who did not complete IES assessment because of emotional distress as equivalent to having PTSD-related symptoms, and we used multiple imputation for the other participants with missing data [22]. Ten data sets were created with missing IES values replaced by imputed values. The model used to impute IES values included patient and family member demographic variables, patient status at 28 days along with study group, and the presence or not of relatives during the resuscitation. The results from analyzing the individual imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rules [23]. In addition, a secondary analysis based on whether or not relatives were given the option to witness CPR was made for the different outcomes regarding the psychological status of relatives. The fact that both analyses converge toward the same conclusion makes it more reliable.

Data are reported as means (±SD) or medians (25th–75th percentiles) for continuous variables and as percentages for qualitative variables. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used for categorical outcomes and mixed models of ANOVA were used for quantitative outcomes, using center as a random effect and adjusting for the relative’s relationship to the patient. When necessary, normalizing transformation was performed. We also assessed whether participants’ IES or HADS scores increased or decreased between the 90-day and 1-year interviews (∆IES and ∆HADS). All statistical tests were two-tailed with a type one error of 0.05 and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical tests were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

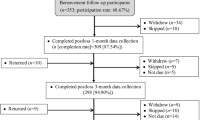

Among the 570 family members (ITT population), 408 (72 %) were evaluated at 1 year (observed cases population), among which 239 (59 %) were given the option to witness resuscitation (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference between the numbers of patients not assessed according to study group.

Psychological assessment

In the intention-to-treat population (N = 570), family members had PTSD-related symptoms significantly more frequently in the control group than in the intervention group [adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.1–3.0; P = 0.02] and among family members to whom physicians did not offer the option to witness CPR versus family members that were given the opportunity to witness resuscitation (adjusted odds ratio, 1.7; 95 % CI 1.1–2.6; P = 0.02).

Analyses of psychological variables in observed cases population (N = 408) according to randomized groups and proposal of family presence are reported in Table 1. Similar results were obtained between the two randomized groups when we considered only patients with an IES score available at 90 days (P = 0.01; Table 1). The proportion of family members presenting symptoms of depression evaluated by HADSD or MINI score was significantly higher in the control group and among family members to whom physicians did not offer the option to witness CPR. ICG score and presence of complicated grief were significantly more important in the control group and among family members to whom physicians did not offer the option to witness CPR (Table 1).

Progression of psychological outcomes

The median difference in IES and HADS scores did not reach statistical significance between the randomized groups: ∆IES = 2.5 (95 % CI [−5, 10]) in the control group and ∆IES = 3 (95 % CI [−4, 12]) in the intervention group, P = 0.34; ∆HADS = 2 (95 % CI [−1, 5]) in the control group and ∆HADS = 1 (95 % CI [−2, 6]) in the intervention group, P = 0.71. This was likewise true when groups were allocated by proposal of family presence: ∆IES = 3 (95 % CI [−5, 11]) in the non-proposal group and ∆IES = 3 (95 % CI [−4, 11]) in the proposal group, P = 0.69; ∆HADS = 2 (95 % CI [−2, 5]) in the non-proposal group and ∆HADS = 1 (95 % CI [−1, 5]) in the proposal group, P = 0.55.

Discussion

In this multicenter, randomized trial, 1-year post-event assessment confirms the positive results on psychological parameters observed at 3 months after cardiac arrest of a relative when family members were offered the opportunity to witness CPR. Interestingly, we observe that the rate of complicated grief (measured by ICG score) is lower when the relative is offered the option of witnessing CPR. Our results provide evidence that adverse bereavement may be reduced by adopting specific attitudes and behaviors toward family presence during resuscitation.

Clearly, emergency physicians are not ready to systematically adopt this attitude. A recent French report and a survey realized after our 3-month results showed that less than 30 % of physicians were willing to allow the family to observe the resuscitation [24, 25]. Similarly, studies that evaluated family members’ involvement in the end-of-life decision-making in ICU found that ICU clinicians need more training in the knowledge and skills of effective communication with families of critically ill patients [26]. A qualitative study by Lind and colleagues reported that relatives want a more active role in end-of-life decision-making. The clinician’s expression “wait and see” hides and delays the communication of honest and clear information [27]. During CPR, families need to understand and agree to basic guidelines in order to maintain efficient resuscitation efforts. The support person must remain with the family, providing constant information, explaining interventions, interpreting medical jargon, and discussing patient responses to treatment and expected outcome. Of course, a strong communication guide must be available in the medical unit and the protocol must address obtaining the consent of the whole resuscitation team. Our protocol has been elaborated and published with our 3-month results [12]. A few other studies obtained good results using similar methodology, especially in ICUs [6].

Bereavement, grief, and mourning are universal experiences. While normal grief is not defined as a mental disorder, pathological grief (complicated or traumatic) is now distinguished in the International Classification of Mental Diseases [2]. Complicated grief has been shown in numerous studies to form a symptom cluster for psychological disorders comprised of symptoms of traumatic distress and separation distress [28–31]. One study found that traumatic grief predicts negative health outcomes, such as cancer, heart disease, and suicidal ideation [3]. Indeed, traumatic grief appears to have critical importance in determining the risk for long-term health morbidity. Moreover, complicated grief must be treated as a specific disorder to be distinct from depression and anxiety [31]. This fact may explain why we did not observe a significant increase of anxiety symptoms in the control group whereas the percentage of depression was higher in the control group and among family members to whom physicians did not offer the option to witness CPR.

Conclusion

Bereavement-related PTSD symptoms, depression, and traumatic grief were less frequent when families were permitted to be present during resuscitation. This benefit persists 1 year after the traumatic event. Allowing some family members to remain near the patient during resuscitation facilitates the grief process and prevents mental and physical morbidity related to traumatic grief.

References

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, Larche J, Liotier J, Papazian L, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B (2005) Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171:987–994

Bourgeois ML (2006) Qualitatives and quantitative methods in grief studies. Ann Med Psychol (Paris) 164:278–291

Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF 3rd, Shear MK, Day N, Beery LC, Newsom JT, Jacobs S (1997) Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. Am J Psychiatry 154:616–623

Prigerson HG, Frank E, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF, Anderson B, Zubenko GS, Houck PR, Georges CJ, Kupfer DJ (1995) Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. Am J Psychiatry 152:22–30

Ricard-Hibon A, Chollet C, Saada S, Loridant B, Marty J (1999) A quality control program for acute pain management in prehospital critical care medicine. Ann Emerg Med 34:738–744

Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, Barnoud D, Bleichner G, Bruel C, Choukroun G, Curtis JR, Fieux F, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Georges H, Goldgran-Toledano D, Jourdain M, Loubert G, Reignier J, Saidi F, Souweine B, Vincent F, Barnes NK, Pochard F, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E (2007) A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 356:469–478

Robinson SM, Mackenzie-Ross S, Campbell Hewson GL, Egleston CV, Prevost AT (1998) Psychological effect of witnessed resuscitation on bereaved relatives. Lancet 352:614–617

Doyle CJ, Post H, Burney RE, Maino J, Keefe M, Rhee KJ (1987) Family participation during resuscitation: an option. Ann Emerg Med 16:673–675

Morrison LJ, Kierzek G, Diekema DS, Sayre MR, Silvers SM, Idris AH, Mancini ME (2010) Part 3: ethics: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 122:S665–S675

Downar J, Kritek PA (2013) Family presence during cardiac resuscitation. N Engl J Med 368:1060–1062

McClenathan BM, Torrington KG, Uyehara CFT (2002) Family member presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a survey of US and international critical care professionals. Chest 122:2204–2211

Jabre P, Belpomme V, Azoulay E, Jacob L, Bertrand L, Lapostolle F, Tazarourte K, Bouilleau G, Pinaud V, Broche C, Normand D, Baubet T, Ricard-Hibon A, Istria J, Beltramini A, Alheritiere A, Assez N, Nace L, Vivien B, Turi L, Launay S, Desmaizieres M, Borron SW, Vicaut E, Adnet F (2013) Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med 368:1008–1018

Meyers TA, Eichhorn DJ, Guzzetta CE, Clark AP, Klein JD, Taliaferro E, Calvin A (2000) Family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitation. Am J Nurs 100:32–42 quiz 43

Mian P, Warchal S, Whitney S, Fitzmaurice J, Tancredi D (2007) Impact of a multifaceted intervention on nurses’ and physicians’ attitudes and behaviors toward family presence during resuscitation. Crit Care Nurse 27:52–61

Horowitz M, Wilner M, Alvarez W (1979) Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Med 41:209–218

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370

Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF 3rd, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, Frank E, Doman J, Miller M (1995) Inventory of complicated grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 59:65–79

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar G (1998) The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview. J Clin Psychiatry 59(Suppl 20):22–33

Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Hubert P, Canoui P, Grassin M, Zittoun R, le Gall JR, Dhainaut JF, Schlemmer B (2001) Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med 29:1893–1897

Bourgeois ML (2004) Les deuils traumatiques. Stress et Trauma 4:241–248

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Bonora LI, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF, Dunbar GC (1997) Reliability and validity of the MINI international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): according to the SCID-P. Eur Psychiatry 12:232–241

Compton S, Levy P, Griffin M, Waselewsky D, Mango L, Zalenski R (2011) Family-witnessed resuscitation: bereavement outcomes in an urban environment. J Pall Med 14:715–721

Rubin DB (1987) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, New York

Belpomme V, Adnet F, Mazariegos I, Beardmore M, Duchateau FX, Mantz J, Ricard-Hibon A (2013) Family-witnessed resuscitation: nationwide survey of 337 out-of-hospital emergency teams in France. Emerg Med J 30:1038–1042

Colbert JA, Adler JN (2013) Clinical decisions. Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation—polling results. N Engl J Med 368:e38

Antonelli M, Bonten M, Chastre J, Citerio G, Conti G, Curtis JR, De Backer D, Hedenstierna G, Joannidis M, Macrae D, Mancebo J, Maggiore SM, Mebazaa A, Preiser JC, Rocco P, Timsit JF, Wernerman J, Zhang H (2012) Year in review in intensive care medicine 2011: I. Nephrology, epidemiology, nutrition and therapeutics, neurology, ethical and legal issues, experimentals. Intensive Care Med 38:192–209

Lind R, Lorem GF, Nortvedt P, Hevroy O (2011) Family members’ experiences of “wait and see” as a communication strategy in end-of-life decisions. Intensive Care Med 37:1143–1150

Latham AE, Prigerson HG (2004) Suicidality and bereavement: complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide Life Threaten Behav 34:350–362

Meert KL, Donaldson AE, Newth CJ, Harrison R, Berger J, Zimmerman J, Anand KJ, Carcillo J, Dean JM, Willson DF, Nicholson C, Shear K (2010) Complicated grief and associated risk factors among parents following a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Archiv Pediatr Adolesc Med 164:1045–1051

Chen JH, Bierhals AJ, Prigerson HG, Kasl SV, Mazure CM, Jacobs S (1999) Gender differences in the effects of bereavement-related psychological distress in health outcomes. Psychol Med 29:367–380

Boelen PA, Prigerson HG (2007) The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults: a prospective study. Eur Archiv Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 257:444–452

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique 2008 of the French Ministry of Health and by the Research Delegation of the Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris (Aurélie Guimfack and Christine Lanau). We are indebted to Martine Tanke, who monitored the ongoing results of the trial; to the physicians, nurses, and ambulance attendants of each center for their valuable cooperation with the study; to Malika Chafai for her secretarial assistance. This study was funded solely by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique 2008 of the French Ministry of Health.

Conflicts of interest

No author has a conflict of interest with regard to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Take-home message: The long-term benefits on post-traumatic stress disorder and depression to being offered the possibility of witnessing resuscitation are still present at 1 year. The incidence of traumatic grief is diminished when a family member is offered the possibility of witnessing CPR.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01009606.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jabre, P., Tazarourte, K., Azoulay, E. et al. Offering the opportunity for family to be present during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: 1-year assessment. Intensive Care Med 40, 981–987 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3337-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3337-1