Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to define the core (minimum) competencies required of a specialist in adult intensive care medicine (ICM). This is the second phase of a 3-year project to develop an internationally acceptable competency-based training programme in ICM for Europe (CoBaTrICE).

Methodology

Consensus techniques (modified Delphi and nominal group) were used to enable interested stakeholders (health care professionals, educators, patients and their relatives) to identify and prioritise core competencies. Online and postal surveys were used to generate ideas. A nominal group of 12 clinicians met in plenary session to rate the importance of the competence statements constructed from these suggestions. All materials were presented online for a second round Delphi prior to iterative editorial review.

Results

The initial surveys generated over 5,250 suggestions for competencies from 57 countries. Preliminary editing permitted us to encapsulate these suggestions within 164 competence stems and 5 behavioural themes. For each of these items the nominal group selected the minimum level of expertise required of a safe practitioner at the end of their specialist training, before rating them for importance. Individuals and groups from 29 countries commented on the nominal group output; this informed the editorial review. These combined processes resulted in 102 competence statements, divided into 12 domains.

Conclusion

Using consensus techniques we have generated core competencies which are internationally applicable but still able to accommodate local requirements. This provides the foundation upon which an international competency based training programme for intensive care medicine can be built.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In a recent international survey [1] of specialist training in adult intensive care medicine (ICM) across 41 countries we found substantial variations in specialty ownership, duration, format and methods of assessment. Within Europe alone there were 37 different training programmes with a minimum duration of ICM training required for recognition as a specialist which varied from 3 to 72 months (mode 24 months). Although there are similarities between curricula, there is evidently no international agreement about the ‘end-product’ of training in terms of the competencies expected of a specialist in ICM. This makes it more difficult to attain the European Union objective of free movement of professionals [2, 3], and complicates mutual recognition of qualifications. We therefore established an international partnership of training organisations under the aegis of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and part-funded by the European Commission. Our aim is to develop an internationally acceptable competency-based training programme in intensive care for Europe (CoBaTrICE) and other world regions, by using consensus techniques to develop minimum core competencies for specialists in ICM. This work has previously been presented in abstract form [4, 5, 6].

Methods

National and international organisations with an interest in or responsibility for training in ICM were invited to nominate expert clinicians as representative national coordinators in the project.

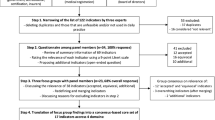

We used a modified Delphi process and a nominal group (NG) [7] to generate and rate the importance of core competencies in ICM, an approach recently used to identify undergraduate competencies in acute care [8] and previously used to identify professional roles [9, 10], curriculum content [11, 12, 13, 14, 15], desired outcomes of national training programmes [8, 16, 17, 18], and prioritisation of research topics in intensive care [19, 20]. The Delphi technique is used to gather and prioritise opinion from large numbers of expert contributors using an iterative process with feedback of individual and group ratings of each item; in its modified form ratings may be omitted and the iterations are limited in number. The nominal group technique uses a small number of people with a facilitator to mediate discussion, thus permitting consideration of concepts in depth. There were three phases (Fig. 1), as described below.

Phase I: generating ideas for competencies

We invited health care professionals and educators to suggest essential competencies for an ICM specialist via a dedicated website. The project was promoted by national coordinators using partnership websites, national and international conferences, and publications; stakeholders were also contacted directly by e-mail. An unlimited number of free-text contributions could be made via the website. A single open-question invited contributors to ‘tell us which competencies are essential for physicians specialising in Intensive Care Medicine’. An example was provided to assist contributors, who were also asked to identify their specialty, country and email address if they wished to participate in the second round of the Delphi. The website was available in six languages (Czech, English, Finnish, Hungarian, Polish and Spanish). All contributions were translated into English by national coordinators before analysis. An option to submit suggestions by email, by post or via national coordinators was also provided. Concurrently patients discharged from intensive care units (ICUs) and relatives of ICU in-patients were invited to participate in a structured survey in order to gain insights into the views of the ‘consumers’ of intensive care. The questionnaire comprised 21 items which could be divided into three categories: (a) medical knowledge and skills, (b) communication and interpersonal skills, (c) decision making. Questionnaires were distributed by local ICU representatives in eight European countries (encompassing northern, central western, central eastern and southern regions) and were returned by post for central analysis. Preliminary results from this survey have been reported [21]; detailed results will form a separate publication. Responses from this consumer survey were integrated with the contributions from the web-based Delphi.

Thirty-seven keywords were derived from ESICM and SCCM guidelines [22, 23, 24, 25, 26], English-language curricula and training guidelines of national ICM training programmes [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] personal communications with national coordinators (for Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Poland) and major textbooks of critical care medicine [33, 34, 35]. All Delphi contributions were categorised by an ICU research nurse (H.B.) using these pre-determined keywords. Multiple keywords were assigned if applicable. Common themes within each category were identified; these multiple contributions were then expressed as single statements by an experienced specialist in ICM (J.B.). The resultant materials were articulated in the form of short phrases, or competence stems, preceded by generic descriptors of level of expertise (derived from the Delphi material), which taken together produced the competence statements (see Appendix and Table 1).

Phase II: nominal group ratings

Members of the NG were professionals with expertise in ICM, and were representative of the first round Delphi respondents in terms of geographical location, profession, specialist background and experience. The group comprised 11 physicians, two of whom were trainees, and one nurse. NG members were asked to identify, in private, the minimum level of expertise (chosen from the generic descriptors) which they considered acceptable for a specialist at the end of ICM training for each competence stem. The resulting data (group mode and range, and personal selection) was made available to each member of the group during a subsequent plenary meeting. The NG met in plenary session, with discussion recorded by a research nurse and moderated by an intensivist who had prior experience in consensus techniques; neither participated in the rating process. To avoid fatigue, participants undertook some preparation before the meeting, spread the work over one and a half days and took regular breaks. Participants were permitted to alter the vocabulary used in the stems to improve clarity, if all members agreed. A two-step process was adopted: the group first discussed each item to agree the minimum level of expertise; then using this agreed level they rated it privately for importance using a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1, unimportant, to 5, very important; Electronic Supplementary Material, ESM Fig. 1). It was agreed before the meeting that if consensus could not be achieved for level of expertise, the lowest level proposed by any NG member would be accepted as the default minimum. This ensured that all items could be rated for importance. The mode was used to analyse level of expertise, mean values were used to determine the group ratings for importance for each item, standard deviations as a measure of disagreement, and mean and standard error to examine the rating characteristics of the members of the NG. We determined in advance that statements rated 4 or higher by the NG would be included in the final set of core competencies; those rated 3 or higher might be included, subject to the comments from the ICM community during the second round Delphi, and statements rated lower than 3 would not be included.

Phase III: recirculation for comment and iterative review

The output from the NG was made available online for 1 month. All first round Delphi participants who provided an email address were contacted and invited to send free-text commentary. National representatives sought the views of their national training organisations and professional colleagues. At the end of this second round comments were analysed by the original reviewers. Modifications included combining common themes to remove discrepancies and reduce repetition, using three rather than four levels of expertise, re-ordering the statements to aid comprehension and categorising them by themed domains. The process of review was overseen by the steering committee and national coordinators, and finally by a specially convened editorial group with clinical and educational expertise, and which reflected both linguistic and cultural diversity.

Results

Phase I: generating ideas for competencies

A total of 536 respondents from 57 countries worldwide participated in the first round online Delphi. The majority of respondents were physicians; 76% were specialists in ICM, 10% trainees and 8.5% other specialists. The remaining respondents included nurses (3%), educators (1%), medical students (1%) and allied health professionals (0.5%). Most (70%) described their primary place of work as a university or university-affiliated hospital.

In total 5,241 suggestions for competencies were received during the 6-month period of data collection (ESM: Fig. 2). The majority (80%) were submitted in English, but suggestions were also made in Polish (8%), Spanish (3.5%), Hungarian (3.5%), Czech (3%), Finnish (1%), Italian (0.5%) and French (0.5%). The median number of suggestions per respondent was 10 (range 1–124).

Suggestions were submitted as single words, phrases or paragraphs with varying descriptive detail. When categorised, suggestions were allocated to all 37 pre-determined keywords; 1,419 (27.1%) suggestions required more than one keyword. The most frequent categories of suggestions were practical procedures (20%), professionalism (‘attitudes and behaviour’ and ‘communication’: 19.6%) and organ system failure/support (all sub-categories: 19.4%; Table 2), irrespective of country of submission or profession (ESM, Figs. 3, 4).

Following iterative content analysis of materials from the online Delphi and consumer questionnaire, all suggestions were encapsulated within 164 competence stems of varying specificity, and 5 behavioural themes. Items from the consumer survey could be linked to 76 of these; only two consumer items were not also represented in the Delphi material. Four levels of expertise (A–D) were identified in the Delphi material (Table 1).

Phase II: nominal group

Changes to stems

Three stems were removed as participants considered that they were already included within others (e.g. ‘intermittent positive pressure ventilation’ was already part of ‘invasive ventilatory support’). Three additional items were proposed and subsequently rated by the NG. Minor changes were made to the wording of 23 items in order to enhance clarity, for example, ‘bronchoalveolar lavage’ changed to ‘bronchoalveolar lavage in the intubated patient’ and the 5 behavioural themes were articulated as competence stems. At the end of this process 169 stems were rated by the NG.

Level of expertise

Complete consensus of minimum level of expertise was not achieved for any of the 164 competence stems by the members of the NG when making their private selection before the plenary meeting. Twenty stems achieved mode level A (‘knowledge of’), 14 mode level B (‘performs under supervision’), 86 level C ‘performs independently’) and 25 level D (‘supervises others’); 19 stems stimulated a bimodal response. During the meeting a minimum level of expertise was agreed for all 169 stems by all participants; in five instances this required the adoption of the default level (i.e. the minimum level proposed by a member of the group) rather than the group consensus. For the majority of stems the consensus level was the same as the mode of the selections made prior to the meeting. For 12 stems it was greater than the mode; all increased from level C to D. At the end of the plenary meeting 38 stems were assigned level A, 18 level B, 74 level C and 39 level D. The concept of the supervisory level of expertise (level D) stimulated the most debate.

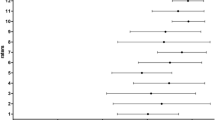

Rating of importance

Once the level of expertise had been agreed, rating of importance was comparatively rapid. A mean rating of 4 or higher (important or very important) was achieved for 111 stems (66% of competence statements); between 3 and 4 (moderately important) for 50 stems (29%) and lower than 3 (minor importance or unimportant) for 8 stems (5%). There was a trend for greater agreement between raters for those competencies given high importance (ESM, Fig. 5). The mean ratings by each member of the NG for all competencies ranged from 3.65 to 4.55 (ESM, Fig. 6).

Phase III-Iteration

During the 4-week consultation period 73 detailed responses were received. These represented the views of both individuals and groups from 23 European countries and 6 in other world regions. More than half of the respondents had contributed to the first round Delphi. Comments were substantially favourable and constructive; they concerned changes in level of expertise, importance and relationship between competencies. There were no criticisms of the choice of competencies. Several additional topics were identified, most of which were either already captured within existing statements or could easily be incorporated through minor re-wording; two new statements were added to the final set of competencies. Proposals to downgrade level of expertise were counterbalanced by proposals to increase it.

Development of the final core competency set

All competencies rated greater than 3 were included in the set. Common themes were merged to reduce repetition and discrepancies, and accommodate local constraints (lack of specific equipment or therapies; ESM, Fig. 7). Low-rated competence statements were not included in the final selection, but themes considered to be important by the second round Delphi respondents were retained within the syllabus: for example, suprapubic catheterisation (rated low) was retained by amending ‘transurethral urinary catheterisation’ (rated high) to ‘urinary catheterisation’. Responding to Delphi comments, we simplified level of expertise by merging levels C and D (independent practice and supervising others). The requirement for trainees to become competent at supervising and delegating safely and teaching others was retained via specific competence statements. Competencies are thus expressed at the level of independent practice unless accompanied by the prefix ‘describes…’ (knowledge), or the suffix ‘…under supervision’ (supervised practice). The relationship between trainee supervision and level of expertise is presented schematically in Fig. 2. Following preliminary development of the syllabus, the editorial group made minor changes to the wording of the statements to improve comprehension, reduce repetition and make statements more inclusive in terms of multiple links to the syllabus. Three themes contained within existing competencies were extracted and reformulated as competence statements. All were then grouped into domains; generic elements within each domain were identified, and a descriptor created to contextualise the theme of the domain. The final competence set consists of 102 competence statements grouped in 12 domains (Table 3).

Discussion

Curriculum development is more of an art than an exact science. We have used the combined experience and wisdom of a large number of ‘stakeholders’ in critical care worldwide, to develop a set of minimum core competencies to describe a specialist in ICM. It should be possible for these competencies to be acquired in any country with ICM services and training infrastructures and for them to be applicable across national borders and professional disciplines.

The emphasis given by Delphi respondents to the importance of professionalism is impressive. This was given a prominence equal to technical ability and demonstrates the value accorded by intensive care clinicians and consumers to attitudes and behaviours, particularly communication skills and self-regulation (‘governance’) and is consistent with increasing concern about the de-professionalism of physicians [36]. Patient safety also emerged as a priority area; it was not specifically identified as a keyword category from existing training programmes, but appeared so frequently in the Delphi material that it warranted presentation in a specific domain.

The NG provided an important forum for mature reflection, focussed discussion and prioritisation by front-line clinicians. A high level of group attention on the task was maintained by fostering an informal atmosphere within a disciplined framework. We found the two-step process of first determining level of expertise before rating importance of great value, since the latter judgements were so clearly influenced by the former. Discussion allowed us to accommodate local variances and to set an achievable safe standard. There was a necessary compromise between desirable training objectives and deliverable training opportunities in an international context. Aspects of training which were considered to be valuable but difficult to deliver universally were assigned a lower minimum level of expertise (e.g. paediatric competencies) to facilitate implementation. However, flexibility in application permits countries to set higher levels of expertise (or include additional competencies) if local factors make this necessary. The competence statements are a compromise between simplicity (‘the trainee is competent in all aspects of intensive care medicine’) and specificity. Detailed aspects of competence will be contained in the syllabus.

Supervision and levels of expertise are complementary aspects of training. We found it necessary to clarify these concepts. The minimum level of expertise can be equated with a maximum level of supervision which should be attained by the end of specialist training (Fig. 2). All trainees by definition are expected to work under specialist supervision, which may be direct or indirect [37] (see Appendix). However, training means a journey towards independent practice during which the trainer must determine the level of supervision required by trainees in relation to their expertise and the needs of the patients.

Our study has a number of potential limitations. Although over 5,000 suggestions were submitted, we may not have captured all relevant competencies. However, all pre-defined keyword categories were used, indicating that the suggestions largely reflected the major components of existing training programmes. The web site was available in only six European languages including English; this might have biased the participant sample, but the universal language of the European medical community is considered to be English. Fatigue or participant disillusionment could be a limitation of internet-based surveys, and might account in part for the disparity in the number of participants from different countries. Relatively few nurses, educators and allied health professionals contributed; there may be scope for the application of relevant competencies to other critical care training programmes (non-medical); however, such wider application would require further consultation with representatives of these allied professions. Finally, the existence of a consensus (the ‘tyranny of the majority’) does not necessarily mean that the ‘correct’ solution has been found; short of observing practice in every country, we may only learn of possible discrepancies when the core competencies are applied to national training programmes. Further iterative review will therefore be required once they are implemented.

Competencies are measurable outcomes of training, assessed in the workplace as knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours (see Appendix), which allow us to make judgements about a clinician's abilities (performance) in a transparent and reproducible manner. As core competencies could be interpreted in conceptually different ways according to national working practices [16], a detailed syllabus and assessment guidelines are required in order to promote standardisation. To assist trainers and trainees the next phases of the CoBaTrICE project will link these competencies to guidance on assessment and to online educational resources.

References

Barrett H, Bion JF on behalf of the CoBaTrICE collaboration (2005) An international survey of training in adult intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 31:553–561

Anonymous (1993) Council Directive 93/16/EEC of 5 April 1993 to facilitate the free movement of doctors and the mutual recognition of their diplomas, certificates and other evidence of formal qualifications. nominal group (NG http://www.ilo.org/public/english/employment/skills/recomm/instr/eu_5.htm (accessed 18 January 2006)

Anonymous (2002) Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 March 2002 on the recognition of professional qualifications. COM 119 final, Official J C181E of 30 July 07 http://europa.eu.int/scadplus/leg/en/cha/c11065.htm (accessed 18 January 2006)

Barrett H, Bion J, Field S, Bullock A, Hasman A, Askham J, Kari A, Mussalo P on behalf of the CoBaTrICE collaboration (2005) Abstract 85N—consensus methodology: developing a competency based training programme in intensive care medicine. AMEE. http://www.amee.org/conf2005/2005_abstracts.pdf (accessed 18 January 2006)

Barrett H, Bion JF on behalf of the CoBaTrICE Collaboration (2005) CoBaTrICE: development of core competencies. Intensive Care Med 31 [Suppl 1]:S220

Barrett H, Bion JF on behalf of the CoBaTrICE Collaboration (2005) CoBaTrICE Core competencies and syllabus development. Crit Care Med 33 [Suppl]:A14

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CFB, Askham J, Marteau T (1998) Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess 2

Perkins GD, Barrett H, Bullock I, Gabbott DA, Nolan JP, Mitchell S, Short A, Smith CM, Smith GB, Todd S, Bion JF (2005) The Acute Care Undergraduate Teaching (ACUTE) initiative: consensus development of core competencies in acute care for undergraduates in the UK. Intensive Care Med 31:1627–1633

Stewart J, O'Halloran C, Harrigan P, Spencer JA, Barton R, Singleton SJ (1999) Identifying appropriate tasks for the pre-registration year: modified Delphi technique. BMJ 319:224–229

McKee M, Priest P, Ginzler M, Black N (1992) Which tasks performed by preregistration house officers out of hours are appropriate? Med Educ 26:51–57

McLeod P, Steinert Y, Meterissan S, Child S (2004) Using the Delphi process to identify the curriculum. Med Educ 38:548

Alahlafi A, Burge S (2005) What should undergraduate medical students know about psoriasis? Involving patients in curriculum development: modified Delphi technique. BMJ 330:633–636

Williams PL, Webb C (1994) The Delphi technique: a methodological discussion. J Adv Nurs 19:180–186

Boath E, Mucklow J, Black P (1997) Consulting the oracle: a Delphi study to determine the content of a post graduate distance learning course in therapeutics. Br J Clin Pharmacol 43:643–647

Walley T, Webb DJ (1997) Developing a core curriculum in clinical pharmacology & therapeutics: a Delphi study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 44:167–170

MacDonald EB, Ritchie KA, Murray KJ, Gilmour WH (2000) Requirements for occupational medicine training in Europe: a Delphi study. Occup Environ Med 57:98–105

Lane DS, Ross V (1994) The importance of defining physicians' competencies: lessons from preventative medicine. Acad Med 69:972–974

Jones J & Hunter D (1995) Qualitative Research: Consensus methods for health services research. BMJ 311:376–380

Vella K, Goldfrad C, Rowan K, Bion J, Black N (2000) Use of consensus development to establish national research priorities in critical care. BMJ 320:976–980

Goldfrad C. Vella K. Bion JF. Rowan KM. Black NA (2000) Research priorities in critical care medicine in the UK. Intensive Care Med 26:1480–1488

Hasman A, Askham J on behalf of the CoBaTrICE collaboration (2005) Abstract 073-CoBaTrICE Survey of patients and relatives in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 31 [Suppl 1]:S23

Thijs LG, Baltopoulos G, Bihari D, Burchardi H, Carlet J, Chioléro R, Dragsted L, Edwards DJ, Ferdinande P, Giunta F, Kari A, Kox W, Planas M, Vincent JL, Pfenninger J, Edberg KE, Floret D, Leijala M, Tegtmeyer FK (ESICM & ESPNIC task force) (1996) Guidelines for a training programme in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 22:166–172

Vincent JL, Baltopoulos G, Bihari D, Blanch L, Burchardi H, Carrington da Costa RB, Edwards D, Iapichino G, Lamy M, Murrillo F, Raphael JC, Suter P, Takala J, Thijs LG (ESICM task force) (1994) Guidelines for training in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 20:80–81

De Lange S, Van Aken H, Burchardi H (2002) European society of Intensive Care Medicine: Intensive care medicine in Europe-structure, organisation and training guidelines of the Multidisciplinary Joint Committee of Intensive Care Medicine (MJCICM) of the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS). Intensive Care Med 28:1505–1511

Dorman T, Angood PB, Angus DC, Clemmer TP, Cohen NH, Durbin CG, Falk JL, Helfaer MA, Haupt MT, Horst HM, Ivy ME, Ognibene FP, Sladen RN, Grenvik ANA, Napolitano LM (2004) Guidelines for critical care medicine training and continuing medical education. Crit Care Med 32:263–272

Anonymous (1997) Guidelines for advanced training for physicians in critical care. American College of Critical Care Medicine of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 25:1601–1607

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (2002) Specific standards for accreditation and specialist training requirements for residency programs in adult critical care medicine. http://rcpsc.medical.org/residency/accreditation/ssas/critcare-adult_e.html (accessed June 2004)

IBTICM (2001) The CCST. In: Intensive care medicine competency based training and assessment. I. A reference manual for trainees and trainers. http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/ibticm/docs/CBTPart1.pdf (accessed June 2004)

ANZICS (2003) Objectives of training in intensive care for the diploma of fellowship of the joint faculty of intensive care medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Royal Australian College of Physicians, 2nd edn

Roca Guiseris et al (2006) SEMICYUY Skill map: ICM specialist's competence. Med Intensiva. (in press)

Anonymous (2004) Curriculum for the Diploma of the Irish board of intensive care medicine (DIBICM). http://www.icmed.com/i_b_i_c_m.htm (accessed June 2004)

Karimi A, Dick W (1997) German Interdisciplinary Association of Critical Care Medicine (DIVI) Excerpt from recommendations on problems in emergency and intensive Care Medicine. DIVI

Webb AR, Shapiro MJ, Singer M, Suter PM (eds) (1999) Oxford textbook of critical care. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bersten AD, Soni N (eds) (2003) Oh's intensive care manual. Butterworth-Heinemann, Edinburgh

Hall JB, Schmidt GA, Wood LDH (1992) Principles of critical care. McGraw-Hill, New York

Royal College of Physicians (2005) Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Report of a working party of the Royal College of Physicians of London. RCP, London. http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/pubs/books/docinsoc/docinsoc.pdf (accessed 18 January 2006)

Royal College of Anaesthetists (2003) The CCST in anaesthesia. I, General principles, sect 5.2, edn, 2 April

Alspach JG (1984) Designing a competency-based orientation for critical care nurses. Heart Lung 13:655–662

McMullan M, Endacott R, Gray M et al (2003) Portfolios and assessment of competence. J Adv Nurs 41:283–294

Acknowledgements

Principle Authors: Dr. J.F. Bion (CoBaTrICE Project lead), H. Barrett (CoBaTrICE Research nurse) on behalf of the CoBaTrICE Collaboration: Steering Committee Partners: A. Augier, D d'Hoir (European Society of Intensive Care Medicine); J. Lonbay, S. Field, A. Bullock,(University of Birmingham); I. Novak (Charles University); J. Askham, A. Hasman (Picker Institute Europe); A. Kari, P. Mussalo, J. Väisänen (Intensium Oy). National Coordinators, National Reporters and Deputies: A. Gallesio, S. Giannasi (Argentina); C. Krenn (Austria); J.H. Havill (Australia, New Zealand); P. Ferdinande, D. De Backer (Belgium); E. Knobel (Brazil); I. Smilov, Y. Petkov (Bulgaria); D. Leasa, R. Hodder (Canada); V. Gasparovic (Croatia); O. Palma (Costa Rica); T. Kyprianou, M. Kakas (Cyprus); V. Sramek, V. Cerny (Czech Republic); Y. Khater (Egypt); S. Sarapuu, J. Starkopf (Estonia); T. Silfvast, P. Loisa (Finland); J. Chiche, B. Vallet (France); M. Quintel (Germany); A. Armaganidis, A. Mavrommatis (Greece); C. Gomersall, G. Joynt (Hong Kong); T. Gondos (Hungary); A. Bede (Hungary); S. Iyer (India); I. Mustafa (Indonesia); B. Marsh, D. Phelan (Ireland); P. Singer, J. Cohen (Israel); A. Gullo, G. Iapichino (Italy); Y. Yapobi (Ivory Coast); S. Kazune (Latvia); A. Baublys (Lithuania); T. Li Ling (Malaysia); A. Van Zanten A. Girbes (The Netherlands); A. Mikstacki (Poland); B. Tamowicz (Poland); J. Pimentel, P. Martins (Portugal); J. Wernerman, E. Ronholm, H. Flatten (Scandinavia); R. Zahorec, J. Firment (Slovakia); G. Voga, R. Pareznik (Slovenia); G. Gonzalez-Diaz, l. Blanch, P. Monedero (Spain); H.U. Rothen, M. Maggiorini (Switzerland); N. Ünal, Z. Alanoglu (Turkey); A. Batchelor, K. Gunning (United Kingdom); T. Buchman (United States). CoBaTrICE Nominal Group: Dr. A. Armaganidis (Greece); Dr. U. Bartels (Germany); Dr. P. Ferdinande (Belgium); Dr. V. Gasparovic (Croatia); Dr. C. Gomersall (Hong Kong); Dr. S. Iyer (India); Dr. A. Larsson (Denmark); Dr. M. Parker (United States); Dr. J.A. Romand (Switzerland); Dr. F. Rubulotta (Italy); Prof. J. Scholes (United Kingdom); Dr. A van Zanten (The Netherlands). The CoBaTrICE Editorial Working Group: J. Bion (Chair); l. Blanch (Spain); C. Gillbe (United Kingdom); T. Gondos (Hungary); D. Grimaldi (France); T. Kyprianou (Cyprus); D. McAuley (United Kingdom); A. Mikstacki (Poland); I. Novak (Czech Republic); D. Phelan (Ireland); G. Ramsay (The Netherlands); E. Ronholm (Denmark); H.U. Rothen (Switzerland). CoBaTrICE is supported by a grant from the European Union, Leonardo da Vinci programme. Additional support is provided by ESICM, SCCM, GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer (Hong Kong). This research project is supported by the European Critical Care Research Network (ECCRN) of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Additional information

On behalf of The CoBaTrICE Collaboration:

H. Barrett · J.F. Bion ✉ Queen Elizabeth Hospital, University Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Edgbaston, B5 2TT Birmingham, UK email: UniSecICM@uhb.nhs.uk email: h.barrett@bham.ac.uk Tel.: +44-121-6272060 Fax: +44-121-6272062

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix: Glossary

Appendix: Glossary

Competence

The ability to integrate generic professional attributes with specialist knowledge, skills and attitudes and apply them in the workplace.

Competence stem

The topic or activity which can be combined with a descriptor of context and level of expertise to form a competence statement.

Competence statement

A task or activity which can be described in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes, and which can be assessed in the workplace (pl = competencies).

Competency-based training

A strategy which aims to standardise the outcome of training (what sort of specialist will be produced) rather than the educational processes (how the specialist is produced).

Competency-based training programme

A programme which defines the outcomes (competencies) required of physicians at different stages of training, provides guidelines for the assessment of these outcomes and educational resources to support their acquisition within the workplace. Outcomes, articulated as competency statements, are defined in a manner which facilitates integration of knowledge, skills and attitudes and assessment of performance to a common standard during routine clinical work.

Curriculum

The entire training programme.

Descriptors of level of expertise

Descriptive terms used to indicate the depth of experience required (for example: ‘knows’, ‘demonstrates’, ‘performs’, ‘manages’) and the criteria by which the specialist will be judged on a particular topic (for example, ‘describes’ would require knowledge to be recited; ‘performs’ would require demonstration of a task being undertaken).

Direct Supervision

The supervisor is working directly with the trainee, or can be present within seconds of being called [37].

Domain

A collection of competence statements grouped by a common theme.

Indirect supervision

The supervisor is not working directly with the trainee. The supervisor may be: (a) local, on the same geographical site, is immediately available for advice, and is able to be with the trainee within 10 min of being called, or (b) remote, rapidly available for advice but is off the hospital site and/or separated from the trainee by more than 10 min. [37]

Level of expertise

The depth of experience required by the specialist in order to be considered competent. Three generic levels have been used: knowledge, supervised practice, independent practice. These levels are intended to guide action rather than dictate it for all circumstances. For example, independent practice thus does not require the specialist to perform all aspects of care alone; this level of practice may vary from recognising a clinical situation in which assistance is required (independently) and seeking help (independently), through to managing the situation independently. It is the decision making and associated action which is known about, performed under supervision or performed independently.

Supervisor

The person with the most appropriate skills for that task and environment in which supervision is occurring; it does not imply ownership by a particular specialty. In general terms supervision of an ICM trainee will be provided by a specialist in ICM with due attention to multidisciplinary practice.

Syllabus

All the knowledge, skills and attitudes in the curriculum; everything a trainee can learn (derived from [1, 37, 38, 39]).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

The CoBaTrICE Collaboration. Development of core competencies for an international training programme in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med 32, 1371–1383 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-006-0215-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-006-0215-5