Abstract

Purpose

The current longitudinal study examines the temporal association between different types of intimate partner violence (IPV) at early adulthood (21 years) and subsequent depression and anxiety disorders in young adulthood (30 years).

Methods

Participants were from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy. A cohort of 1529 was available for analysis. IPV was measured using the Composite Abuse Scale at 21 years. At the 21 and 30-year follow-ups, major depression disorder and anxiety disorders were measured using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Results

We found a temporal relationship between almost all forms of IPV at 21 years and females’ new cases of major depression disorder at 30 years. This association was not found for females who had previously been diagnosed with depression disorder. IPV did not predict the onset of new anxiety disorders, but it had a robust association with anxiety disorders in females with a previous anxiety diagnosis. We observed no significant link between IPV and males’ subsequent major depression disorder. Interestingly, the experience of emotional abuse was a robust predictor of new cases of anxiety disorders but only for males.

Conclusion

Our results suggest the need for sex-specific and integrated interventions addressing both IPV and mental health problems simultaneously. IPV interventions should be informed by the extend to which pre-existing anxiety and depression may lead to different psychological responses to the IPV experience. Increased risk of anxiety disorders predicted by emotional abuse experienced by males challenges beliefs about invulnerability of men in the abusive relationships and demands further attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a prevalent public health concern across the world, associated with short-term and long-term negative outcomes [1,2,3,4,5,6]. There is growing evidence, suggesting that those who have experienced IPV are at increased risk of mental health problems [7,8,9].

Despite having relatively large samples, most previous studies have been cross-sectional and have not allowed for the possibility of pre-existing mental health problems for those experiencing IPV. Furthermore, much of the longitudinal research has been restricted to IPV and depression [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]; there is a paucity of evidence about the other mental health outcomes of IPV including anxiety [18, 19]. Moreover, previous longitudinal studies have some limitations in controlling for key potential confounders [9]. It is possible that any association between IPV and mental health may reflect other factors related to both exposure and outcome. This includes childhood exposure to family violence, experience of childhood sexual abuse, and living with parents who experienced mental health problems [20, 21].

The short-term association between IPV and mental health problems has previously been addressed [12, 15, 16]. However, IPV is unlikely to be a one-time exposure. It is likely to be a recurrent and ongoing occurrence [22] and its effect on mental health may occur over an extended period of exposure [23]. In any event, the temporal order of IPV and mental health problems remains to be determined. In one longitudinal study of a nationally representative cohort, Ouellet-Morin et al. [17] tested the directionality of associations between IPV and depression. Excluding women with a history of depression, they found that IPV independently predicted new-onset depression. Beside research suggesting that IPV may lead to a subsequent poor mental health, an extensive body of literature has identified a higher risk of IPV victimization in women with severe mental illness [24,25,26,27]. There is also some evidence of a bidirectional association between IPV and poor mental health [9, 19]. These findings highlight the need to adjust for pre-existing mental health in testing the association between IPV and subsequent mental health.

There are inconsistent findings about sex differences in the experience of IPV, suggesting that disparities in definitions, methods, measurements, and samples may produce different estimates of sex differences in some forms of IPV. While a great deal of the literature has affirmed higher rates of violence males perpetrate against their female partners [28,29,30], there are population surveys, suggesting that males and females experience IPV victimization at similar rates [31, 32]. This latter body of research, however, may not include abused females in safe houses or violent males in jails. Arguably, the use of the Conflict Tactics Scale [33] may not address the gendered context of IPV and capture sex differences in the severity of IPV victimization and its harmful consequences [34, 35]. A few longitudinal population studies assessing sex differences in the mental health of those who have experienced IPV have shown that even with similar rates of IPV, females may be more vulnerable to the negative consequences of IPV such as depression and PTSD [19, 36].

The current study examines whether different types of IPV experiences in early adulthood (21 years) are associated with subsequent depression and anxiety disorders in young adulthood (30 years). We report data from a population-based prospective cohort study, which includes females and males. We control for potential confounders and pre-existing mental health disorders, and investigate whether experiences of IPV independently predict new cases of depression and anxiety disorders.

Method

Participants

Participants are from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP), which is a longitudinal birth cohort study in Brisbane, Australia. Some 7223 mothers attending their first clinic visit at Brisbane’s Mater Hospital and their children were followed up at child’s birth, 6 months after birth, 5, 14, 21, and 30 years later. The initial inclusion criteria, sampling, and study design have been described elsewhere [37]. For the current study, we included only offspring for whom there were data involving lifetime mental health disorders at 21 and 30 years using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview [CIDI; 38. The present study involves a cohort of 1528 offspring including 891 (58.3%) female and 638 male respondents. The mean age at the 21-year follow-up was 20.8 years (SD ± 0.9). Participants' racial background was Caucasian (92.8%), Asian (3.4%), and Aboriginal and Islander (3.7%). At 21 years of age, about 23.3% of respondents were below the then Australian poverty line and less than 25.7% of offspring had a post high school educational qualification. Some 2.8% of respondents were married, 55.0% were living together, and 7.7% had children.

Measurement

Intimate partner violence

IPV was measured using a modified version of the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) at 21 years. This scale is a validated and comprehensive self-report measure, which assesses frequency of ever having experienced violence in intimate relationships (in either current or prior relationships) [39, 40]. In the current study, the CAS consists of four separate subscales of severe combined victimization (2 items included being raped and assaulted with a weapon), physical abuse (7 items included being hit, thrown, pushed, shaken; Cronbach's alpha = 0.89), emotional abuse (11 items included being kept apart from friends and family, insulted, blamed; Cronbach's alpha = 0.90), and harassment (4 items included being followed, harassed over the telephone or at work; Cronbach's alpha = 0.71). Each item was rated on a 6-point response scale: never (= 0), only once (= 1), several times (= 2), once a month (= 3), once a week (= 4), and daily (= 5). For each subscale, scores were summed and dichotomized into two categories of abused (= 1) and not abused (= 0, reference group), according to the recommended cut-offs (severe combined abuse (≥ 1), physical abuse (≥ 1), emotional abuse (≥ 3), and harassment (≥ 2). In addition, respondents who experienced at least one type of IPV were recoded into abused and those who did not report any type of IPV were categorized into not abused.

Mental health disorders

Major depression disorder and anxiety disorders [including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social and specific phobia, generalized anxiety, and panic disorder] were measured using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The CIDI-Auto is a structured and standardized diagnostic interview developed for general population use, and for the assessment of lifetime and recent mental disorders including depression and anxiety disorders [38]. The CIDI-Auto uses criteria based upon the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV; [41]). In the current study we used the CIDI-Auto to assess lifetime diagnoses of DSM‐IV major depression disorder and anxiety disorders at both 21-year and 30-year follow-ups.

Potential confounders

In the multivariable analyses, the associations between IPV and depression and anxiety disorders were adjusted for a range of socio-demographic variables. At the baseline, these variables included parents’ ethnicity (Caucasian, Asian and Aboriginal/Islander), maternal education (incomplete high school and higher), and family income (< $10,399 and higher). Mother’s quality of marital relationships was measured using the Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale [42] and comprised two categories of good adjustment and conflict. Maternal depression was measured by a seven-item subscale of the Delusions-Symptoms-States Inventory at first clinic visit. Mothers with four symptoms and more were categorized as having had symptoms of depression [43].

In addition to the baseline variables, we added a number of covariates collected at the 21-year follow-up. All young participants were about 21 years of age, so we did not adjust for the age differences in the cohort. In the 21-year follow-up, young offspring were asked about their current marital status (single/never married, living together, married, or separated), education level (high school or less, diploma, and higher), and personal income (low (< $7900) and higher). Their history of sexual child abuse was also measured using the question “did you experience being pressured or forced to have sexual contact before 16 years?”.

Statistical analysis

In Table 1, we compared males and females for the study variables using odds ratios. We then combined two lifetime CIDI diagnosis statuses of respondents at 21 and 30 and created four categories of those with no diagnosis, those who had no history of disorder at 21 but met the criteria for disorder at 30 (new cases since 21 years), those who met the criteria of disorder at 21 years but not at 30 years (recovered), and respondents who were diagnosed with disorder at 21- and 30-year follow-ups (persistently diagnosed). A sex-based comparison for each group using a univariable logistic regression was conducted and presented in the Supplementary Table S1. In Tables 2 and 3, we performed a series of hierarchical and stratified univariable and multivariable logistic regressions between each form of IPV at 21 follow-up and depression and anxiety disorders at 30-year follow-up, separately for females and males. We performed the analysis for the whole sample, those with a history of mental health disorders, and new cases since 21-year follow-up. The hierarchical regressions were chosen to examine whether the primary associations between specific forms of IPV and subsequent mental health disorders (Model 1) were robust after adjustment for pre-existing condition (Model 2) and potential confounders (Model 3). To supplement the sex-stratified analysis, we conducted the logistic regression analysis to test for an interaction effect of sex (female = 0, male = 1) and each form of IPV at 21 (not abused = 0; abused = 1) on subsequent mental health disorders (no = 0, yes = 1). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression are reported by odds ratios (OR) and with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

Missing data

Of the cohort of 7223 participants in FCV, about 1528 offspring completed the IPV questionnaire at 21 years and CIDI at 21- and 30-year follow-ups (Supplementary Figure S1). To assess the possibility of attrition bias affecting the results, we conducted a propensity analysis and repeated the regression analyses using a variable representing the characteristics of the sample at baseline including sex, maternal education, family income, quality of marital relationships, parental racial background, and maternal depression [44]. To do this analysis, in SPSS, we used logistic regression to calculate a propensity score of the association between the baseline confounding variables and the predictor variables of interest (forms of IPV). This propensity weighting was then used in subsequent regression outcome models instead of the individual confounders (Supplementary Table S2).

Results

Table 1 compares male and female offspring on potential covariates, forms of IPV victimization, and DSM-IV lifetime major depression and anxiety disorders at 21 and 30 years. At 21 years, males experienced physical abuse and females experienced severe combined abuse more often. Overall, males reported higher rates of experiencing at least one type of intimate victimization than did females. In the 21- and 30-year follow-ups, females exhibited higher rates of major depression and anxiety disorders. We also found that females were more likely to develop new cases of both depression and anxiety disorders than did males (Supplementary Table S1).

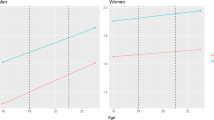

Table 2 presents the associations between IPV at 21 years and major depression disorder at 30 years in males and females. In the unadjusted model, almost all forms of IPV predict new cases of major depression disorder in females, but not in males. In model 3, after adjusting for the pre-existing depression disorder at 21 years, the primary effects of physical and emotional abuse and harassment on 30-year major depression disorder were no longer statistically significant for females. Only severe combined IPV remained significant in predicting major depression disorder at 30 years. However, excluding females with a history of major depression disorder, severe combined abuse [AOR = 2.7 (1.0, 7.4)], physical abuse [AOR = 1.8 (1.1, 3.0)], and emotional abuse [AOR = 1.5 (1.0, 2.6)] had robust associations with new cases of depression disorder at 30 years. We could not find significant relationships between IPV and subsequent major depression disorder in females who had a pre-existing depression.

Table 3 shows univariable and multivariable associations between IPV at 21 years and anxiety disorders at 30 years in both males and females. We found that emotional abuse predicts new cases of anxiety disorders in males, but not in females. However, we found significant associations between physical and emotional abuse and harassment and later anxiety in females who had a history of anxiety disorders.

We also assessed whether interaction terms between sex and forms of IPV, adjusted for potential covariates, predict mental health disorders at 30 years. Consistent with the findings in Table 2, we found that the association between physical abuse and new cases of depression disorder differs for males and females, adjusting for potential confounders (OR = 0.3, CI95 = 0.1–0.8, p = 0.02). This finding suggests a sex difference in the association between physical abuse and new cases of major depression disorder.

Attrition was greater in males compared to females (71.0% vs. 58.2%) and Aboriginal/Islanders compared to Caucasian participants (80.6% vs. 63.1%). There was also higher attrition among offspring of teenage (73.7% vs. 63.1%) or uneducated (72.2% vs. 63.1%) mothers, and among those who were living in low-income families (70.0% vs. 61.0%). Findings from repeated analyses with propensity scores based on baseline confounders showed that attrition did not affect the direction and magnitude of the associations (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

In this study, we have followed a cohort of 1529 males and females over 9 years to assess sex differences in mental health consequences of IPV victimization. We found that the associations between IPV and subsequent mental health disorders are different in those who had/did not have a pre-existing condition. We found a temporal relationship between almost all forms of IPV victimization at 21 years and major depression disorder at 30 years in females who had not previously had a major depression disorder. This finding was not observed in females who had previously been diagnosed with major depression disorder. We had a different finding when prediction females’ anxiety disorder. IPV did not predict new onset of anxiety disorders, but it had a robust association with anxiety disorders in females with a previous diagnosis. We observed no significant link between IPV and males’ subsequent major depression disorder, neither in those with or without a pre-existing depression. Interestingly, males’ experience of emotional abuse was a robust predictor of new cases of anxiety disorders.

Our finding of an association between IPV and females’ major depression disorder suggests two pathways: first, depression disorder may arise independently from the IPV experience across life-stages [45], and second, IPV may lead to the onset of major depression diagnoses in females who have previously been free of depression. By contrast, we observed that female IPV survivors with a history of anxiety disorders are more likely to experience subsequent anxiety disorder. This may be explained by the differences between depression and anxiety in sensitivity and reactivity to stressors (here IPV victimization). Compared to females with no previous anxiety disorder, females diagnosed with anxiety disorders may show stronger response to interpersonal stressors, engage in negative self-evaluation, and experience intensified and prolonged negative emotions. Furthermore, females with anxiety may have a greater sensitivity to being abused by a romantic partner than do females with depression [46, 47].

Our data suggest a clear sex difference in the association of IPV and new cases of major depression disorder. This finding is consistent with one longitudinal study in which females’ but not males’ depressive symptoms were associated with the experience of IPV victimization [19]. A possible explanation for this might be that males and females react differently to the stress/trauma of interpersonal violence, with females being more likely to internalize stress symptoms and become depressed [48]. Another possibility is that females might experience depression, because the abuse has been more frequent or severe [49]. Females in the current study reported higher rates of severe combined abuse than did males (OR: 3.2; CI 1.7, 6.2). It is also possible that even for the same form of IPV, males and females experience the actual abuse differently. Although, our data showed that males report physical abuse more often, the experience of physical abuse might be more frequent and physically severe for females than for males [50]. Anderson [34] argues that the sex-symmetry research has failed to determine sex differences/similarities in severity and consequences of IPV. Most studies suggesting similar rates of IPV in males and females simply reduce sex to what females and males do and neglect the gendered nature of IPV rooted in social structures. Female violence is not equal to male’s violence, in terms of characteristics, correlates, and consequences [51]. One longitudinal study found that even in female-dominated or mutually violent relationships, females experience more adverse health outcomes [36]. Another study, having followed male and female adolescents through adulthood, found that although both males and females reported similar rates of IPV, females were more likely to develop depression and PTSD than males [19]”.

The higher rates of physical abuse reported by males in the current study should be interpreted in the context of general population sample that is unlikely to include battered women or very violent men. Furthermore, the physical abuse subscale in the CAS includes items which measure non-severe and gender-neutral violent acts which may be perpetrated equally by males and females [52]. It is also possible that the IPV measure used in the current study cannot determine whether victimized males have been involved in a bidirectional violence or are the primary perpetrator of IPV.

We found that only males with no history of anxiety disorders developed new cases of anxiety disorders following emotional abuse victimization. The longitudinal literature on consequences of emotional IPV in men is limited. Some cross-sectional studies have indicated that higher psychological abuse, including emotional and verbal abuse, has a stronger association with mental health outcomes than do physical abuse, in both males and females [53, 54]. A body of research on battered women has suggested that psychological abuse is more strongly associated with PTSD (as a type of anxiety) than physical abuse [55,56,57]. A possible explanation is that psychological victimization directly attacks one’s self-concept, and may cause PTSD and anxiety through mechanisms like guilt, self-hatred, and regret [56]. Anxiety, itself, may be associated with shame and embarrassment especially in males, as it is interpreted as a vulnerability and weakness for males who have been socialized to a more dominant self-perception [58].

Our findings should be interpreted with caution. There is a possibility that the study sample may not be representative of the population. The baseline sample of MUSP included pregnant women from the lower to middle socio-economic status who had attended a public hospital. Arguably, their offspring have become more representative of the Australian population [37, 59]. Since our findings are based on only one partner’s self-report of victimization, there may be a risk of self-serving bias [60]. Hence, we cannot exclude the possibility that survivors in this study may be involved in a bidirectional violence or be the primary perpetrator of IPV rather than the victim. It has been well documented that emotional and physical abuse often co-occur, and it is essential to control for their concurrent effects [56, 61, 62]. However, in the current study, we modelled each form of IPV separately and did not adjust forms of IPV for each other. Small numbers in some cells made a separate analysis impractical. In addition, small sample size, particularly in the severe combined victimization, was associated with wide confidence intervals and decreased the statistical power and precision of the estimates. Another limitation of this study was lack of information on the reverse relationship between major depression and anxiety disorders predicting IPV victimization. In the 21-year follow-up, we measured lifetime ever mental health disorders as well as lifetime exposure to IPV, which made a causal inference impossible at that time. However, while we had some data on depression/anxiety at 14 years and could examine if adolescence mental health problems predict IPV, the use of a different measure of depression and anxiety, the length of time between the 14- and 21-year follow-ups, and the small numbers in some cells reduce the value of such comparison. Despite including several key confounders, unmeasured confounding factors still may bias our results. Finally, loss to follow-up may have biased some results. Multiple studies on MUSP, however, have found that the attrition minimally affects estimates of association [37, 59, 63]. In the current study, the propensity analyses, however, suggested that the results are unlikely to be affected by selection bias.

Conclusion and implications

The findings of this study point to a temporal relationship from IPV victimization and subsequent mental health disorders. We also found different results for females with and without pre-existing depression disorder. Although the temporal order is useful in determining which risk factor should be targeted for interventions, our mixed results suggest a more integrated intervention addressing both IPV and mental illness simultaneously. A key policy priority should, therefore, be to plan early prevention before adolescents become involved in intimate relationships and develop mental health problems. IPV interventions should be informed by the extent to which pre-existing anxiety and depression may lead to different psychological responses to the IPV experience. We found a sex difference in the association of IPV and depression disorder, which support developing sex-specific interventions. Increased risk of anxiety disorders predicted by emotional abuse experienced by males challenges beliefs about invulnerability of men in the abusive relationships and demands further attention.

Data availability

The data set(s) used in this article is available on request from the MUSP.

References

Campbell JC (2002) Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 359(9314):1331–1336

Plichta SB (2004) Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: policy and practice implications. J Interpers Violence 19(11):1296–1323

Iverson KM, Dardis CM, Pogoda TK (2017) Traumatic brain injury and PTSD symptoms as a consequence of intimate partner violence. Compr Psychiatry 74:80–87

Ansara DL, Hindin MJ (2011) Psychosocial consequences of intimate partner violence for women and men in Canada. J Interpers Violence 26(8):1628–1645

Sugg N (2015) Intimate partner violence: prevalence, health consequences, and intervention. Med Clin North Am 99(3):629–649

Ellsberg M, Jansen HAFM, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C (2008) Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet 371(9619):1165–1172

Golding JM (1999) Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. J Fam Violence 14(2):99–132

Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, Lo B, Zonderman AB (2012) Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 75(6):959–975

Bacchus LJ, Ranganathan M, Watts C, Devries K (2018) Recent intimate partner violence against women and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ Open 8(7):e019995

Adam EK, Chyu L, Hoyt LT, Doane LD, Boisjoly J, Duncan GJ et al (2011) Adverse adolescent relationship histories and young adult health: cumulative effects of loneliness, low parental support, relationship instability, intimate partner violence, and loss. J Adolesc Health 49(3):278–286

Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Kohn R (2006) Intimate partner violence and long-term psychosocial functioning in a national sample of American women. J Interpers Violence 21(2):262–275

Chowdhary N, Patel V (2008) The effect of spousal violence on women's health: findings from the Stree Arogya Shodh in Goa India. J Postgrad Med 54(4):306–312

Lindhorst T, Oxford M (2008) The long-term effects of intimate partner violence on adolescent mothers' depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med 66(6):1322–1333

Kim J, Lee J (2013) Prospective study on the reciprocal relationship between intimate partner violence and depression among women in Korea. Soc Sci Med 99:42–48

Davidson SK, Dowrick CF, Gunn JM (2016) Impact of functional and structural social relationships on two year depression outcomes: A multivariate analysis. J Affect Disord 193:274–281

Chuang CH, Cattoi AL, McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Camacho F, Dyer AM, Weisman CS (2012) Longitudinal association of intimate partner violence and depressive symptoms. Mental Health Fam Med 9(2):107–114

Ouellet-Morin I, Fisher HL, York-Smith M, Fincham-Campbell S, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L (2015) Intimate partner violence and new-onset depression: a longitudinal study of women's childhood and adult histories of abuse. Depress Anxiety 32(5):316–324

Suglia SF, Duarte CS, Sandel MT (2011) Housing quality, housing instability, and maternal mental health. J Urban Health 88(6):1105–1116

Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A (2006) Is domestic violence followed by an increased risk of psychiatric disorders among women but not among men? A longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 163(5):885–892

Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK (2012) A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse 3(2):231–280

Chang DF, Shen BJ, Takeuchi DT (2009) Prevalence and demographic correlates of intimate partner violence in Asian Americans. Int J Law Psychiatry 32(3):167–175

Shortt JW, Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Kerr DC, Owen LD, Feingold A (2012) Stability of intimate partner violence by men across 12 years in young adulthood: effects of relationship transitions. Prev Sci 13(4):360–369

Taris TW, Kompier MAJ (2014) Cause and effect: optimizing the designs of longitudinal studies in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 28(1):1–8

Howard LM, Trevillion K, Khalifeh H, Woodall A, Agnew-Davies R, Feder G (2010) Domestic violence and severe psychiatric disorders: prevalence and interventions. Psychol Med 40(6):881–893

Khalifeh H, Oram S, Osborn D, Howard LM, Johnson S (2016) Recent physical and sexual violence against adults with severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 28(5):433–451

Trevillion K, Oram S, Feder G, Howard LM (2012) Experiences of domestic violence and mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 7(12):e51740

Van Deinse TB, Macy RJ, Cuddeback GS, Allman AJ (2018) Intimate partner violence and sexual assault among women with serious mental illness: a review of prevalence and risk factors. J Soc Work 19(6):789–828

Dobash RE, Dobash R (1979) Violence against wives: a case against the patriarchy. Free Press, New York

Hester M, Kelly L, Radford J (1996) Women, violence, and male power: feminist activism, research, and practice. Open University Press, Buckingham

Yodanis CL (2004) Gender inequality, violence against women, and fear: a cross-national test of the feminist theory of violence against women. J Interpers Violence 19(6):655–675

Straus MA (2011) Gender symmetry and mutuality in perpetration of clinical-level partner violence: empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Aggress Violent Behav 16(4):279–288

Straus MA, Ramirez IL (2007) Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggress Behav 33(4):281–290

Straus MA (1979) Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. J Marriage Fam 41:75–88

Anderson KL (2005) Theorizing gender in intimate partner violence research. Sex Roles 52(11–12):853–865

Walby S, Allen J (2004) Domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking: findings from the British Crime Survey: Home Office

Temple JR, Weston R, Marshall LL (2005) Physical and mental health outcomes of women in nonviolent, unilaterally violent, and mutually violent relationships. Violence Vict 20(3):335–359

Najman JM, Bor W, O'Callaghan M, Williams GM, Aird R, Shuttlewood G (2005) Cohort profile: The Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP). Int J Epidemiol 34(5):992–997

World Health Organization (1997) Composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI-AUTO). WHO, Geneva

Rietveld L, Lagro-Janssen T, Vierhout M, Lo Fo Wong S (2010) Prevalence of intimate partner violence at an out-patient clinic obstetrics-gynecology in the Netherlands. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 31(1):3–9

Lokhmatkina NV, Kuznetsova OY, Feder GS (2010) Prevalence and associations of partner abuse in women attending Russian general practice. Fam Pract 27(6):625–631

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Spanier GB (1976) Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam 38:15–28

Bedford A, Foulds GA, Sheffield BF (1976) A new personal disturbance scale (DSSI/sAD). Br J Soc Clin Psychol 15(4):387–394

Beal S, Kupzyk K (2014) An Introduction to propensity scores: what, when, and how. J Early Adolesc 34:66–92

Minor KL, Champion JE, Gotlib IH (2005) Stability of DSM-IV criterion symptoms for major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 39(4):415–420

Valdez CE, Lim BH, Lilly MM (2013) “It’s going to make the whole tower crooked”: victimization trajectories in IPV. J Fam Violence 28(2):131–140

Farmer AS, Kashdan TB (2015) Stress sensitivity and stress generation in social anxiety disorder: a temporal process approach. J Abnorm Psychol 124(1):102–114

Chaplin TM, Hong K, Bergquist K, Sinha R (2008) Gender differences in response to emotional stress: an assessment across subjective, behavioral, and physiological domains and relations to alcohol craving. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32(7):1242–1250

Pimlott-Kubiak S, Cortina LM (2003) Gender, victimization, and outcomes: reconceptualizing risk. J Consult Clin Psychol 71(3):528–539

Romito P, Grassi M (2007) Does violence affect one gender more than the other? The mental health impact of violence among male and female university students. Soc Sci Med 65(6):1222–1234

Weston R, Temple JR, Marshall LL (2005) Gender symmetry and asymmetry in violent relationships: patterns of mutuality among racially diverse women. Sex Roles 53(7):553–571

Ahmadabadi Z, Najman JM, Williams GM, Clavarino AM, d'Abbs P (2017) Gender differences in intimate partner violence in current and prior relationships. J Interpers Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517730563

Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM et al (2002) Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med 23(4):260–268

Howard LM, Trevillion K, Agnew-Davies R (2010) Domestic violence and mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry 22(5):525–534

Taft CT, Murphy CM, King LA, Dedeyn JM, Musser PH (2005) Posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology among partners of men in treatment for relationship abuse. J Abnorm Psychol 114(2):259–268

Street AE, Arias I (2001) Psychological abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in battered women: examining the roles of shame and guilt. Violence Vict 16(1):65–78

Kemp A, Green BL, Hovanitz C, Rawlings EI (1995) Incidence and correlates of posttraumatic-stress-disorder in battered women—shelter and community samples. J Interpers Violence 10(1):43–55

Zimmerman J, Morrison AS, Heimberg RG (2015) Social anxiety, submissiveness, and shame in men and women: a moderated mediation analysis. Br J Clin Psychol 54(1):1–15

Najman JM, Alati R, Bor W, Clavarino A, Mamun A, McGrath JJ et al (2015) Cohort profile update: the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP). Int J Epidemiol 44(1):78

Perry AR, Fromuth ME (2005) Courtship violence using couple data: characteristics and perceptions. J Interpers Violence 20(9):1078–1095

Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ (2000) Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering. Am J Public Health 90(4):553–559

Krebs C, Breiding MJ, Browne A, Warner T (2011) The association between different types of intimate partner violence experienced by women. J Fam Violence 26(6):487–500

Saiepour N, Najman JM, Ware R, Baker P, Clavarino AM, Williams GM (2019) Does attrition affect estimates of association: a longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res 110:127–142

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the MUSP research team, the Schools of Public Health and Social Sciences (The University of Queensland), and also the Research Training Program of the Australian Government and the University of Queensland for sponsorship.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council and Australian Research Council (NHMRC grant #1009460). The principal author is in receipt of “the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship” and “the University of Queensland Centennial Scholarship”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The Mater Hospital and University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP) in Australia has been approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of the University of Queensland. Additional approval granted from the Human Ethics Research Office of the University of Queensland (Clearance number 2017001622) to undertake the present study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants of the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmadabadi, Z., Najman, J.M., Williams, G.M. et al. Intimate partner violence and subsequent depression and anxiety disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 611–620 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01828-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01828-1