Abstract

Purpose

Chronic medical conditions are a risk factor for the onset of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adults. However, few studies have examined this association in adolescents. The present study explored the association between chronic medical conditions and the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in an adolescent sample representative of the U.S.A. population.

Method

Using data from the National Comorbidity Survey—Adolescent Supplement (10,148 Americans between ages 13–17), discrete-time survival analyses were performed to examine the odds of developing suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts, given prior presence of a chronic medical condition. Multivariate models controlled for sociodemographic factors and the presence of comorbid mental health conditions. Post-hoc sensitivity analyses examined associations between timing of chronic medical condition onset and later suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Results

Multivariate analyses showed that dermatological conditions, asthma, allergies, headache, and back/neck pain were associated with elevated odds of suicidal ideation, while cardiovascular conditions were associated with increased odds of suicide attempts. Additionally, cardiovascular conditions were associated with increased risk of suicide planning and attempts among adolescents with suicidal ideation. Chronic medical conditions that began in adolescence were associated with the greatest risk of later suicidal thoughts and behaviors, compared to chronic medical conditions that began in early or middle childhood.

Conclusion

Consistent with research in middle and older adults, physical health conditions are associated with increased risk for the onset of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents. Mental health screening for adolescents with chronic medical conditions may help parents and physicians identify suicidality early.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While any life cut short—by whatever means—is jarring, few things are more tragic than the suicide of youth. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults in the U.S., amounting to an annual loss of over 6000 young people below the age of 24 years [1]. Unfortunately, despite expanding knowledge regarding important suicide risk factors and emerging support for psychosocial prevention and intervention programs [2], suicide rates in the U.S. have been increasing steadily since at least the year 1999 [3]. Further, estimated suicide rates do not take into account other facets of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) such as suicidal ideation, suicide planning, or halted or otherwise unsuccessful suicide attempts, which affect 12.1%, 4.0%, and 4.1% of adolescents, respectively [4]. Clearly, STBs are an important health concern in youth.

Over the past 2 decades, the relationship between chronic medical conditions (CMCs), poor physical health, and STBs has received increasing attention. According to major theories of suicidal behavior, CMCs may directly and indirectly increase risk by decreasing one’s sense of belonging, pain tolerance, and available coping resources while increasing feelings of hopelessness, burdensomeness, entrapment, lack of control, and desire for escape [5, 6]. Consistent with these theories, elevated rates of STBs are well documented among adults with CMCs, poor health status, and physical disability [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Much of this literature, however, has focused on the elderly [7,8,9, 12, 14], with relatively few studies in younger populations. Among the various CMCs that have been examined, epilepsy, chronic respiratory conditions, frequent severe migraines, and other chronic pain conditions have been most robustly associated with increased risk of STBs [15, 16].

Although the association between CMCs and STBs in adults is well established, less is known about this association in earlier developmental periods [17, 18]. Of the studies that have examined STBs and CMCs in adolescents, most have used small, non-representative clinical samples, focused on a single medical condition and a single STB-related outcome (e.g., suicidal ideation among adolescents with migraines) or collapsed across types of CMCs [19, 20]. Furthermore, many have lacked important statistical controls to account for sources of variance that could inflate risk estimates (e.g., controlling for the presence of co-occurring mental health conditions) [19, 20]. Given that many CMCs and STBs have an onset in adolescence, investigating this association in youth under 18 years old is an important direction for research [4, 21]. Moreover, understanding how the developmental timing of CMC onset (e.g., childhood versus adolescent onset) impacts later STBs may help to identify youth who are at especially high risk for developing STBs.

The present study sought to address these aforementioned gaps in knowledge using data from the National Comorbidity Survey—Adolescent Supplement, a cross-sectional epidemiological survey of over 10,000 adolescents residing in the U.S. [22]. Specifically, we examined whether the prior presence and developmental timing of eleven distinct CMCs were associated with elevated risk for STBs. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the associations between CMCs and STBs in a representative community sample of adolescents, thereby providing important information regarding the population-level associations between physical conditions that affect youth and a significant health outcome, onset of STBs.

Methods

Sample and procedures

Data for this study came from the National Comorbidity Survey—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), an epidemiological survey designed to examine the prevalence, age-of-onset distributions, course, and comorbidity of DSM-IV disorders among U.S. adolescents [23]. Details regarding the design, validity, and field procedures of the study can be found elsewhere [22,23,24,25,26,27]. Briefly, the NCS-A surveyed 10,148 adolescents between the ages of 13–17 (although some turned 18 before the date of their interview) in the continental U.S. between February 2001 and January 2004 using a dual sampling frame (households and schools). Sample weightings were applied to adjust for the probability of selection and differences between the final sample and overall U.S. population on a variety of demographic and geographic variables, resulting in weighted estimates that closely matched the 2000 U.S. Census demographics [25].

The NCS-A interview schedule was based on an adapted version of the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) [28]. Adolescents in the sample completed a computer-assisted personal interview assessing lifetime presence and age of onset of a variety of mental and physical health conditions [28]. Additionally, a parent, guardian, or other parental surrogate (hereafter, “parents”) responded to a self-administered questionnaire (n = 6491) or a short-form telephone interview (n = 1994) regarding the adolescent’s physical and mental health history, as well as some sociodemographic factors [23].

All procedures for the NCS-A study were approved by the human research ethics boards of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. Parents provided written informed consent and adolescents provided written informed assent of their participation in the study. Adolescents and parents were paid $50 each as compensation for their participation. Restricted NCS-A data were accessed through an agreement between the Inter-university Consortium of Political and Social Research and the third author (Turner). Secondary analysis of these data was approved by the research ethics board of the University of Victoria.

Measures and variables

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors

As part of the NCS-A computer-assisted CIDI 3.0 interviews, each adolescent received the suicidal ideation probe question: “Have you ever experienced… seriously thinking about killing yourself?”. Skip protocols in the survey dictated that an affirmative answer was required to receive further questions about suicidal thoughts (e.g., “How old were you the first time… you seriously thought about killing yourself?”) and the inquiry suite for suicide planning and attempts (“…You made a plan for killing yourself”, “…You tried to kill yourself”, respectively). Suicide attempt questions were asked regardless of the answer to suicide plan questions, allowing for the distinction between planned and unplanned suicide attempts. For each STB reported, adolescents were asked how old they were (in years) when they first experienced this STB. For the present analyses, adolescents who triggered a skip protocol by denying suicidal ideation were treated as if they had denied planning or attempting suicide despite not answering these questions.

Chronic medical conditions

To assess physical health, adolescents were asked: “Have you ever had … arthritis; chronic back or neck problems; frequent or very bad headaches; any other chronic pain; seasonal allergies like hay fever; acne or other serious skin problems?”. They were then asked: “Did a doctor or other health professional ever tell you that you had … heart problems; diabetes or high blood sugar; serious stomach or bowel problems like an ulcer or colitis; HIV infection or AIDS; epilepsy or seizures; herpes or any other venereal disease; cancer?”. For each condition reported, adolescents were asked how old they were (in years) when they were first diagnosed with or experienced the condition. Similarly, parents were asked if their child had ever experienced: “Allergies or hay fever; asthma; epilepsy or seizures; frequent or very bad headaches or migraine headaches; heart problems; severe acne; skin problems other than acne (such as eczema, psoriasis); serious stomach trouble (such as gastritis, ulcers); venereal disease (such as genital herpes, gonorrhea)?”. Parents who responded to the self-administered questionnaire were also asked to provide the age of onset of any condition they endorsed for their child. Parents who responded to the short-form questionnaire were not asked this question and thus were considered as having missing values for the age-of-onset questions.

Consistent with procedures to resolve discrepancies in adolescent and parent reports regarding mental health diagnoses, we used an “OR” rule to combine parent and adolescent reports of CMCs, such that an affirmative response from either party (i.e., parent “OR” adolescent) would override a dissenting or missing value from the other. For any discrepancies in age of onset, we used the youngest age given by either the parent or adolescent. HIV/AIDS, herpes or other venereal disease, and cancer could not be included in our analyses due to low prevalence in the NCS-A sample and reliability. Overall, the NCS-A data allowed us to consider the presence/absence and age of onset for the following eleven CMCs: cardiovascular disease (i.e., heart problems), dermatological conditions (i.e., clinically severe acne or skin problems such as eczema, psoriasis), gastrointestinal disease (i.e., serious stomach or bowel problems such as gastritis, ulcers), diabetes, epilepsy, asthma, allergies, arthritis, headache, back and neck pain, and other pain conditions.

DSM-IV mental disorders

Adolescents completed the structured computerized CIDI 3.0 interviews assessing the following mental health disorders: panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder (I or II), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and substance abuse/dependence for alcohol or illicit drugs. To maximize validity, parents also provided information on five disorders where diagnosis is most reliably made with the inclusion of informant reports: major depressive disorder, dysthymia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. The NCS-A examined DSM-IV mental disorders because the CIDI was developed based on the DSM-III-R Structured Clinical Interview, and the CIDI 3.0 that was used in the NCS-A studies was developed to operationalize DSM-IV criteria and improve validity [26]. Further details regarding the reliability, validity, and scope of CIDI 3.0 interviews in the NCS-A, as well as rationale for use of DSM versus ICD-10 guidelines based on reappraisal studies, can be found elsewhere [26]. For the purposes of the present study, we computed a single dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the adolescent met criteria for any mental disorder.

Sociodemographic covariates

Adolescent and parent reports were used to calculate a variety of demographic characteristics, including adolescents’ age, sex (male or female), ethnicity (originally described in the NCS-A data set as “race”: White, Black, Hispanic, or other), regional density or urbanicity of primary residence (rural, urban, or metropolitan), ratio of total family income to the poverty line (from poorest to wealthiest: ≤ 1.5, ≤ 3, ≤ 6, or > 6), and household composition (living with 0, 1, or 2 biological parents). Apart from age, all covariates were treated as dichotomous dummy-coded variables.

Statistical analyses

To examine the associations between CMCs and subsequent onset of STBs, we created separate person-year files for each STB (suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts, as well as planned and unplanned attempts among adolescents with ideation) wherein each year of an adolescent’s life was treated as a unique observational record up to and including the first year of onset of the STB. The STB of interest was coded as “1” on a time-varying dichotomous variable in the year of onset and as “0” in all previous years. Any records after the first year of onset of a STB were censored. All time-varying predictors (CMCs and mental health conditions) were time-lagged such that they were coded as 1 in the year after the initial year of onset (remaining coded as 1 until termination of the person-year file), and as 0 in the year of onset and prior years. For example, if an adolescent reported onset of diabetes at age 11, it was coded as 0 in their 11th person-year file and as 1 in their 12th person-year file, to only predict a STB onset in their 12th year. Time-lagged predictor variables, while conservative, remove uncertainty with respect to the relative timing of a predictor and outcome that occur in the same year. All analyses were weighted using the total sample weights (“FINAL_WEIGHT” variable). Analyses with cell sizes of fewer than 10 respondents were censored due to low power, estimate reliability (e.g., very wide confidence intervals), and to protect participant privacy in accordance with the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) Agreement regulating the use of the NCS-A data.

We first examined the bivariate associations between each CMC and STB using weighted discrete-time survival analysis to estimate the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals associated with prior presence of a CMC and subsequent onset of STBs. Next, we examined time-invariant sociodemographic factors (age, sex, ethnicity, urbanicity, family income, family make-up) that were associated with each STB and constructed multivariate models that included significant sociodemographic covariates and all of the time-varying CMCs simultaneously. This allowed us to examine the unique contributions of each CMC to each STB. These unique associations refer to the independent associations between each individual CMC and each STB after having controlled for the influence of sociodemographic correlates and comorbid CMCs. To explore contributions of CMCs above and beyond mental health conditions, we examined a final multivariate model covaried for mental health conditions, providing the most stringent and conservative estimate of the unique associations between CMCs and STBs. Finally, to examine whether the associations between CMCs and STBs varied by developmental timing of CMC onset, we conducted post-hoc sensitivity analyses for any CMC that had a significant bivariate association with STBs. Consistent with prior studies, we coded CMCs as having emerged during early childhood (0–5 years of age), middle childhood (6–10 years of age), or adolescence (11–18 years of age) [29, 30]. CMC onsets were modelled as categorical variables (with the values of 1, 2, and 3, in order of increasing age), and adolescent onset was used as the reference category against which early and middle childhood were compared. With respect to the issue of multiple testing, no corrections were made because the aims of this study did not focus on evaluating the general null hypothesis [31], and multivariate models already provide a degree of robustness against family-wise error. Moreover, because our time-lagged predictors provide conservative estimates of effects by considering only cases where the onset of CMCs preceded STBs by at least 1 year, the use of additional multiple testing corrections such as a Bonferroni method would increase the rate of Type II errors, potentially obscuring important differences [31].

Results

Discrete-time survival analyses

Bivariate estimates for the associations between each CMC and STB, as well as the number of respondents answering affirmatively for each condition, are provided in Table 1. Most CMCs, apart from diabetes and epilepsy, were positively associated with suicidal ideation and suicide planning among adolescents with ideation. Cardiovascular conditions [bivariate odds ratios (ORs) = 1.9–5.4], headaches (bivariate ORs = 1.7–3.2) and back/neck pain (bivariate ORs = 1.3–6.9) were most strongly and consistently associated with onset of STBs. Suicide attempts were significantly associated with cardiovascular disease and headache, while the transition from ideation to attempt was associated with cardiovascular disease, headache, and back/neck pain. No significant negative associations were found.

Multivariate estimates for the associations between CMCs and STBs, adjusted for significant sociodemographic covariates, can be found in Table 2. Cardiovascular conditions remained associated with most STBs, except suicidal ideation, and were the only conditions found to be positively associated with suicide attempts (OR = 2.9) and the transition from ideation to attempts (OR = 4.8). Dermatological conditions, asthma, allergies, headaches and back/neck pain were each uniquely associated with elevated risk of suicidal ideation (ORs = 1.4–4.0), while arthritis, asthma, headaches and back/neck pain were each uniquely associated with the escalation of STBs from ideation to planning (ORs = 1.9–3.7).

Multivariate estimates for the associations between CMCs and STBs with additional adjustment for the presence (versus absence) of any DSM-IV mental health condition can be found in Table 3. Of the 7518 adolescents who reported having at least one CMC, 3431 reported at least one co-occurring mental health condition. Even in this stringent model, cardiovascular diseases remained associated with most STBs, except suicidal ideation, and were the only CMC that was significantly associated with making a suicide attempt (OR = 2.8) and transitioning from ideation to attempt (OR = 4.1). Dermatological conditions, asthma, headache, and back/neck pain retained unique associations with the onset of suicidal ideation (ORs = 1.3–2.9), while arthritis, asthma, headaches, and back/neck pain continued to be associated with the escalation of STBs from ideation to planning even after controlling for mental health conditions (ORs = 1.7–3.2).

Post-hoc sensitivity analyses

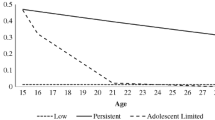

Post-hoc sensitivity analyses examining the importance of developmental timing of CMC onset (which can be found in Table 4) revealed that onset of CMCs in adolescence was more strongly associated with later onset of STBs than onset of CMCs in early or middle childhood. For almost all CMCs that had significant bivariate associations with suicidal ideation, the odds of developing ideation were significantly lower when CMCs began in early or middle childhood, relative to adolescence. More specifically, the odds of developing suicidal ideation given early childhood and middle childhood onset of CMCs were 20% and 50% those associated with adolescent onset of CMCs, respectively. Similarly, adolescent onset CMCs were associated with greater risk for suicide planning and attempts, compared to childhood-onset CMCs.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the associations between multiple types of CMCs and a variety of STBs in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. There are three key findings. First, the results suggest that several CMCs are uniquely associated with elevated risk for STBs, consistent with previous literature underscoring the association between physical health and suicide risk [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Specific CMCs that were uniquely associated with STBs include dermatological conditions, asthma, allergies, headache, back/neck pain, and cardiovascular conditions. Second, while dermatological, respiratory, and pain conditions were associated with elevated risk of suicidal ideation and planning, cardiovascular conditions were uniquely associated with suicide attempts and the transition from ideation to attempt. Thus, these findings contribute to a growing literature that differentiates risk factors for suicidal thoughts versus suicidal behaviors [15, 16, 32], consistent with an ideation-to-action framework [33]. Third, post-hoc sensitivity analyses revealed a novel finding: CMCs that began in adolescence posed the greatest risk for subsequent STBs, compared to onset in early and middle childhood. In interpreting this finding, it is important to keep in mind that adolescence is associated with rapid increasing rates of STBs, making this a potentially sensitive developmental period for the onset of STBs [4]. However, this finding also opens the possibility that adolescents may be uniquely vulnerable to stress associated with CMC development. Whereas younger children may have access to familial, educational, and health system supports that can help buffer the effects of CMCs, adolescents may receive fewer such supports. Additionally, the social and societal pressures placed on adolescents may increase their vulnerability to feelings of hopelessness, lack of control, and desire to escape, particularly if CMC onset results in social isolation or exclusion from peers [21, 34]. Prospective studies tracking children’s and adolescents’ adjustment to CMCs are essential in clarifying possible pathways to STBs.

The present results diverge from the existing literature in at least one important way. Unlike previous studies that identify epilepsy and seizure conditions as risk factors for STBs, this study did not find a significant association between epilepsy and STBs [16, 17, 35]. There are several possible explanations for this result. First, there was a relatively low incidence of epilepsy in the NCS-A sample. Second, the severity and duration of symptoms and impairment experienced by this community-based sample might be relatively mild or include primarily juvenile epilepsy. This may attenuate an otherwise strong association between more severe and chronic forms of epilepsy and STBs that have been observed in clinically recruited samples. Third, epilepsy and seizure disorders may be less impairing in childhood and adolescence given the supports that are often available in primary and secondary schools relative to later in life.

It is important to note several limitations of the present study. First, the NCS-A study was neither prospective nor specifically designed to retrospectively assess the course, correlates, or contexts of CMCs or STBs. Thus, information regarding important processes of adjustment to illness, coping, and illness course was not captured in these surveys. Prospective studies that examine possible mediators and moderators of the associations between CMCs and STBs will help to understand sources of variability in the observed associations. Second, since the NCS-A is a community sample, the results may not generalize to clinical samples or populations who experience more severe and potentially disabling CMCs. Most of the NCS-A sample was recruited from schools, suggesting respondents likely had relatively good health status. Third, the present study lacks information regarding medication usage. Previous studies have identified several medications as important mediators of the relationship between CMCs and STBs. For instance, leukotriene-modifying agents that are present in several asthma medications appear to account for the positive association between asthma and STBs [36, 37]. Similarly, interferon-α2b and ribavirin have been identified as a potential mechanism-linking hepatitis C and STBs [38, 39], while anticonvulsants are strongly associated with STBs [40]. Future studies should assess adolescents’ use of medications and other treatments to manage CMCs to provide a fuller picture of possible mechanisms of risk.

In terms of clinical implications, we know that most adults with CMCs who die by suicide see a physician in the months before their deaths [9], providing a very strong potential point of intervention. The present study suggests that CMCs, particularly those that emerge during adolescence, pose a risk for the subsequent onset of STBs. Parents and physicians should be aware of this increased risk. The use of mental health screening measures for adolescents with CMCs, particularly severe and impactful conditions such as cardiovascular disease, may help identify STBs early and before they escalate. By identifying CMCs as a risk factor for later STBs in adolescence, this research ultimately represents an important step towards reducing the distressingly high number of adolescent suicides in the U.S. and globally.

References

National Institute of Mental Health (2015) Suicide. Natl. Institutes Heal. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide/index.shtml. Accessed 5 July 2017

Calear AL, Christensen H, Freeman A et al (2016) A systematic review of psychosocial suicide prevention interventions for youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25:467–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0783-4

CDC (2018) CDC Vital signs report: suicide rising across the US. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/vs-0618-suicide-H.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2018

Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I et al (2013) Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. JAMA Psychiatry 70:300–310. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55

O’Connor RC, Kirtley OJ (2018) The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 373:20170268. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

Joiner TE (2005) Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press, Harvard

Erlangsen A, Stenager E, Conwell Y (2015) Physical diseases as predictors of suicide in older adults: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50:1427–1439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1051-0

Fässberg MM, Cheung G, Canetto SS et al (2016) A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults. Aging Ment Health 20:166–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1083945

Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP et al (2004) Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 164:1179–1184. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.11.1179

Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, Newsom JT (2007) Physical illness, functional limitations, and suicide risk: a population-based study. Am J Orthopsychiatry 77:56–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.56

Kye SY, Park K (2017) Suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among adults with chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study. Compr Psychiatry 73:160–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.12.001

Quan H, Arboleda-Flórez J, Fick GH et al (2002) Association between physical illness and suicide among the elderly. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 37:190–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270200014

Ratcliffe GE, Enns MW, Belik S-L, Sareen J (2008) Chronic pain conditions and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic perspective. Clin J Pain 24:204–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e31815ca2a3

Waern M, Rubenowitz E, Runeson B et al (2002) Burden of illness and suicide in elderly people: case-control study. BMJ 324:1355. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7350.1355

Scott KM, Hwang I, Chiu W-T et al (2010) Chronic physical conditions and their association with first onset of suicidal behavior in the world mental health surveys. Psychosom Med 72:712–719. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e3333d

Scott KM, Chiu WT, Hwang I et al (2012) Chronic physical conditions and the onset of suicidal behavior. In: Nock MK, Borges G, Ono Y (eds) Suicide: global perspectives from the WHO world mental health surveys. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 164–178

Greydanus DE, Calles J (2007) Suicide in children and adolescents. Prim Care Clin Off Pract 34:259–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2007.04.013

Greydanus D, Patel D, Pratt H (2010) Suicide risk in adolescents with chronic illness: implications for primary care and specialty pediatric practice: a review. Dev Med Child Neurol 52:1083–1087

Ikeda RM, Kresnow MJ, Mercy JA et al (2001) Medical conditions and nearly lethal suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav 32:60–67. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.32.1.5.60.24207

Wang S-J, Fuh J-L, Juang K-D, Lu S-R (2009) Migraine and suicidal ideation in adolescents aged 13–15 years. Neurology 72:1146–1152. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000345362.91734.b3

Sawyer SM, Drew S, Yeo MS, Britto MT (2007) Adolescents with a chronic condition: challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet 369:1481–1489. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60370-5

Kessler RC (2011) National comorbidity survey: adolescent supplement (NCS-A), 2001–2004. Inter-university consortium for political and social research [distributor], Ann Arbor, MI

Merikangas KR, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ et al (2009) National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): i. Background and Measures. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:367–379. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0B013E31819996F1

Gomez SH, Tse J, Wang Y et al (2017) Are there sensitive periods when child maltreatment substantially elevates suicide risk? Results from a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Depress Anxiety 34:734–741. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22650

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ et al (2009) National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): II. Overview and design. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:380–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0B013E3181999705

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green J et al (2009) National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:386–399. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0B013E31819A1CBC

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ et al (2009) Design and field procedures in the US national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 18:69–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.279

Kessler RC, Üstün TB (2004) The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 13:93–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.168

Dunn EC, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N et al (2013) Developmental timing of child maltreatment and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in young adulthood:results from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Depress Anxiety 30:955–964. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22102

Kaplow JB, Widom CS (2007) Age of onset of child maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol 116:176–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.176

Perneger TV (1998) What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ Br Med J 316:1236. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.316.7139.1236

Barnes AJ, Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD et al (2010) Suicide and self-injury among children and youth with chronic health conditions. Pediatrics 125:889–895. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1814

Klonsky ED, Saffer BY, Bryan CJ (2018) Ideation-to-action theories of suicide: a conceptual and empirical update. Curr Opin Psychol 22:38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COPSYC.2017.07.020

Suris J-C, Michaud P-A, Viner R (2004) The adolescent with a chronic condition. Part I: developmental issues. Arch Dis Child 89:938–942. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2003.045369

Jones JE, Hermann BP, Barry JJ et al (2003) Rates and risk factors for suicide, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in chronic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 4:31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.08.019

Favreau H, Bacon SL, Joseph M et al (2012) Association between asthma medications and suicidal ideation in adult asthmatics. Respir Med 106:933–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2011.10.023

Schumock GT, Lee TA, Joo MJ et al (2011) Association between leukotriene-modifying agents and suicide: What is the evidence? Drug Saf 34:533–544. https://doi.org/10.2165/11587260-000000000-00000

Voaklander DC, Rowe BH, Dryden DM et al (2008) Medical illness, medication use and suicide in seniors: a population-based case control study. J Epidemiol Community Heal 62:138–146. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.055533

Dieperink E, Ho SB, Tetrick L et al (2004) Suicidal ideation during interferon-??2b and ribavirin treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 26:237–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.01.003

Patorno E, Bohn RL, Wahl PM et al (2010) Anticonvulsant medications and the risk of suicide, attempted suicide, or violent death. JAMA 303:1401. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.410

Acknowledgements

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044,780), and the John W. Alden Trust. The work of the authors (Dean-Boucher, Robillard, and Turner) was not supported by any additional funding source. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dean-Boucher, A., Robillard, C.L. & Turner, B.J. Chronic medical conditions and suicidal behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 329–337 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01770-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01770-2