Abstract

Purpose

The everyday lives of unemployed people with mental health problems can be affected by multiple discrimination, but studies about double stigma—an overlap of identities and experiences of discrimination—in this group are lacking. We therefore studied multiple discrimination among unemployed people with mental health problems and its consequences for job- and help-seeking behaviors.

Methods

Everyday discrimination and attributions of discrimination to unemployment and/or to mental health problems were examined among 301 unemployed individuals with mental health problems. Job search self-efficacy, barriers to care, and perceived need for treatment were compared among four subgroups, depending on attributions of experienced discrimination to unemployment and to mental health problems (group i); neither to unemployment nor to mental health problems (group ii); mainly to unemployment (group iii); or mainly to mental health problems (group iv).

Results

In multiple regressions among all participants, higher levels of discrimination predicted reduced job search self-efficacy and higher barriers to care; and attributions of discrimination to unemployment were associated with increased barriers to care. In ANOVAs for subgroup comparisons, group i participants, who attributed discrimination to both unemployment and mental health problems, reported lower job search self-efficacy, more perceived stigma-related barriers to care and more need for treatment than group iii participants, as well as more stigma-related barriers to care than group iv.

Conclusions

Multiple discrimination may affect job search and help-seeking among unemployed individuals with mental health problems. Interventions to reduce public stigma and to improve coping with multiple discrimination for this group should be developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Unemployment and mental illness often co-occur [1,2,3] and may interact in a vicious circle, with mental health problems being cause or consequence of unemployment [4]. On one hand, unemployment can result in psychological distress [5,6,7]; on the other hand, there is evidence from longitudinal studies that poor mental health causes unemployment [8] and premature retirement [4, 9]. However, unemployed people with mental health problems often choose not to use mental health services or job-seeking support [10] and therefore do not benefit from available psychosocial therapies [11] or supported employment [12]. Besides other factors such as mental health literacy, the stigma associated with unemployment and with mental illness can affect help- and job-seeking behaviors [10].

Mental illness stigma is common and describes a process that involves labeling, stereotypes, separation, status loss, and discrimination [13, 14]. There are three forms of stigma that can be barriers to help-seeking: public stigma, self-stigma and structural stigma [15]. The latter involves macro level units rather than individuals, for example increased waiting times as a consequence of limited funding for mental health services. Public stigma (i.e. stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination among members of the general public) and self-stigma (if people with mental illness agree with negative stereotypes and turn them against themselves) additionally contribute to low help-seeking behavior [16]: People with mental illness may avoid treatment in order not to be labeled “mentally ill” by others; and self-stigma or shame can undermine the motivation to seek help [17].

Unemployed people with mental health problems may additionally experience everyday discrimination associated with their unemployment status. The general public often associates unemployment with incompetence [18], and especially young people tend to blame unemployed individuals, unless own experience of unemployment weakens these prejudices [19]. Unemployment can result in loss of self-esteem and in social withdrawal [10]. This can lead to reduced job search self-efficacy [20, 21], the belief that one can successfully seek and find a job [22].

Nevertheless most previous studies among people with mental health problems have looked at mental illness stigma without considering other social conditions that may be stigmatized such as unemployment [23]. Multiple stigma might increase distress among affected individuals and limit the effectiveness of existing help-seeking interventions. One concept reflecting the implications of multiple stigma is intersectionality. The idea was initially developed within feminist psychology to describe how overlapping stigmatized social identities affect the level and quality of oppression and disadvantage experienced by African American women [24]. Accordingly, intersectionality highlights the need for considering intersections of social identities (e.g. gender, age, sexual orientation, obesity) as well as related systems of discrimination to comprehensively understand stigma [25, 26]. According to the double disadvantage hypothesis [27] individuals with more than one disadvantaged status may experience worse outcomes than their singly disadvantaged counterparts. However, findings have been inconsistent. In a recent population survey, von dem Knesebeck and colleagues [28] found no evidence for increased stigma towards people with depression who were of low socio-economic status or immigrants as compared to high socio-economic status persons and non-migrants. On the other hand, Grollman et al. [27] observed negative cumulative health effects among persons experiencing multiple forms of discrimination.

In terms of multiple stigma among unemployed people with mental health problems, the consequences for job search and help-seeking behavior are unclear. In a large English study among people using health services, employed participants reported significantly lower levels of experienced mental health-related discrimination in different areas of life compared to unemployed individuals [29]. O´Donnell et al. [30] tested the impact of anticipated social discrimination on psychological distress and somatic symptoms in a sample of unemployed individuals and found that participants with higher anticipated unemployment-related discrimination reported greater distress as well as more physical health problems.

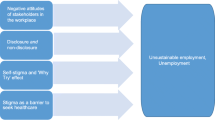

Because individuals who experience multiple discrimination may encounter greater barriers to job- and help-seeking, associations between multifactorial discrimination and mental health inequities [31] as well as discrimination as a barrier to health utilization matter [32]. To develop adequate services and to increase help-seeking among unemployed individuals with mental health problems, a better understanding of characteristics and consequences of multiple discrimination due to unemployment and mental health problems is needed. In this study, we therefore focused on two attributions: (1) the attribution of experienced discrimination to unemployment; and (2) the attribution of experienced discrimination to mental health problems. We expected that individuals who attribute discrimination to mental health problems as well as to unemployment would experience worse job- and help-seeking outcomes compared to those participants who do not attribute discrimination to both characteristics.

Methods

Study design and participants

During the AloHA project on unemployment, mental health problems and help-seeking [33, 34], 301 participants were recruited outside healthcare settings and mainly from unemployment agencies in Southern Germany. Inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 64 years, current unemployment and sufficient German language skills. Another inclusion criterion was a score ≥ 13 on the K6 Psychological Distress Scale [35] or a score ≥ 1 on items 2–4 of the CAGE-AID screening tool for current alcohol and substance-use disorders [36]. For the sake of specificity, we excluded item 1 (cut down) from calculating CAGE-AID scores because in previous studies nearly half of healthy controls endorsed that item [37]. In addition to fulfilling either the K6 or CAGE-AID criterion, a score of ≥ 17 (range of possible scores: 12–60) on the 12-item WHO-Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 [38] was needed, corresponding approximately to the 85th general population percentile and to the average disability level of persons with one mental disorder [39]. We therefore only included participants with significant illness-related disability. Persons were excluded if they worked more than 14 h per week, earned more than €450 per month (above this limit, social insurance contributions must be paid in Germany), or received full disability pension. Participants were on average 44 years old (M = 43.7, SD = 11.2) and about half were female. The average length of lifetime unemployment was about 5 years (M = 63.2 months, SD = 56.4).

Measures

Experienced discrimination was assessed by the 9-item Everyday Discrimination (EDD) Scale [40]. Participants rated the extent to which they experienced various forms of discrimination in their everyday lives on a scale from 1/never to 6/almost every day, e.g. “being treated with less courtesy than others or being threatened or harassed”. An EDD sum score was calculated as the sum of all items (range of possible sum scores 9–54; Cronbach's alpha in this sample α = 0.88). Due to participants´ experiences of being unemployed and mentally distressed, individuals were asked to rate their agreement with two statements on 7-point Likert scales (1/strongly disagree to 7/strongly agree): (EDDa) “I am treated like this because I am unemployed” (M = 4.0, SD = 2.2) and (EDDb) “I am treated like this because I am mentally ill/I am mentally distressed” (M = 3.4, SD = 2.0). Based on these two attribution scores, we built subgroups of discrimination attribution to mental health problems and/or to unemployment. For both statements, we classified attribution of discrimination for anyone who scored above the midpoint (> 4) of the attribution scale. Excluding those respondents who did not report any form of experienced discrimination in their everyday lives (EDD sum score = 9, n = 12), this resulted in four subgroups: group i (n = 71) attributed experienced discrimination to both unemployment (EDDa: M = 6.0, SD = 0.8) and mental health problems (EDDb: M = 6.0, SD = 0.8), group ii (n = 128) neither to unemployment (EDDa: M = 2.1, SD = 1.2) nor to mental health problems (EDDb: M = 2.1, SD = 1.1), group iii (n = 70) mainly to unemployment (EDDa: M = 5.9, SD = 0.9; EDDb: M = 2.5, SD = 1.1), and group iv (n = 20) mainly to mental health problems (EDDa: M = 2.6, SD = 1.3; EDDb: M = 5.7, SD = 0.7).

Job search self-efficacy was assessed with an established 6-item measure of job search self-efficacy [41, 42] and respondents rated their confidence to engage in several job search activities, e.g. “making the best impression in an interview”, from 1/not at all confident to 5/a great deal confident, yielding a job search self-efficacy mean score (Cronbach's alpha in this sample α = 0.86). Perceived barriers to seeking help for mental health problems were assessed by the 30-item Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation Scale (BACE [43]). Participants were asked to rate potential barriers on a 4-point Likert scale (1/not at all – 4/a lot). Two mean scores for perceived barriers to help-seeking for mental health problems were calculated; (1) stigma-related barriers (12 items, e.g. “Concern that I might be seen as weak for having a mental health problem”, Cronbach's alpha in this sample α = 0.94) and (2) not stigma-related barriers (18 items, e.g. “Wanting to solve the problem on my own”, Cronbach's alpha in this sample α = 0.91). The Self-Appraisal of Illness Questionnaire (SAIQ [44]) was used to assess perceived need for treatment (6 items, e.g. “I think my condition requires psychiatric treatment”, Cronbach's alpha in this sample α = 0.86) and higher perceived presence of illness (4 items, e.g. “How ill do you think you are?”, Cronbach´s alpha in this sample α = 0.71).

Statistical analyses

We excluded respondents who did not report any form of experienced discrimination in their everyday lives (EDD score = 9, n = 12), so that only 289 participants were included in the final analyses. First, multiple linear regressions on job search self-efficacy, BACE stigma- and not stigma-related barriers, and on need for treatment as well as presence of illness (SAIQ) were calculated (Table 1). Independent variables included level of everyday discrimination, attribution of discrimination to unemployment (EDDa, yes vs. no, as defined above), attribution of discrimination to mental health problems (EDDb, yes vs. no, as above). All regressions were adjusted for age, gender and length of lifetime unemployment. In an additional step and to examine possible interaction effects between attribution of discrimination to unemployment and to mental health problems, we repeated all linear regressions with the interaction term of both attributions (EDDa * EDDb) as additional independent variable. Second and to test for differences in job- and help-seeking behaviors associated with attributions, we compared four subgroups based on the attribution of experienced discrimination to unemployment and to mental health problems (group i), neither to unemployment nor to mental health problems (group ii), mainly to unemployment (group iii) and mainly to mental health problems (group iv). The four subgroups were compared regarding job search self-efficacy, perceived barriers to accessing mental health care, need for treatment and presence of illness using analyses of variance (ANOVA; Table 2) and Scheffé tests for post hoc comparisons. Because both attribution variables (EDDa, EDDb) showed skewed distributions in the subgroups, we repeated the subgroup comparisons with the Kruskal–Wallis test [45]. The significance level was set to p < 0.05 and SPSS 21 was used for all analyses.

Results

In multiple linear regressions, adjusted for age, gender and length of lifetime unemployment, better job search self-efficacy was associated with lower levels of everyday discrimination, less attribution of discrimination experiences to mental health problems and shorter unemployment, explaining about one-ninth of job search self-efficacy variance (Table 1). More perceived stigma-related barriers to care were related to more everyday discrimination and a greater attribution of discrimination to both unemployment and mental health problems; the regression model explained about a third of variance in stigma-related barriers. A higher level of not stigma-related barriers was predicted by more discrimination and a stronger attribution of discrimination to unemployment, explaining about one-sixth of not stigma-related barrier variance. More perceived need for treatment and higher presence of illness were associated with less attribution of discrimination to unemployment and more attribution to mental health problems. When repeating the regressions with the interaction term of both attributions as additional predictor variable, the interaction term was not significant throughout (all p values > 0.12, data not shown).

In ANOVAs and post hoc comparisons using the Scheffé test (Table 2), people who attributed discrimination to both unemployment and mental health problems (group i) showed significantly lower job search self-efficacy than participants who attributed discrimination mainly to unemployment (group iii). Subgroups differed with respect to perceived stigma-related barriers to help-seeking, i.e. participants who attributed discrimination to both unemployment and mental health problems (group i) perceived significantly more stigma-related barriers to help-seeking than those who attributed discrimination mainly to unemployment (group iii) and more than those who attributed discrimination to mental health problems (group iv). No significant differences in not stigma-related barriers between multiple (group i) and single discrimination attribution groups (groups iii and iv) were found. People who attributed discrimination to both unemployment and mental health problems (group i) perceived significantly more need for treatment and higher presence of illness than participants who attributed discrimination mainly to unemployment (group iii). When repeating the subgroup comparisons with the Kruskal–Wallis test and Bonferroni correction for multiple tests, all post-hoc comparisons that were significant in the ANOVAs remained significant.

Discussion

While there is evidence that multiply disadvantaged individuals are more likely to report mental health problems than their singly disadvantaged counterparts [46], most empirical studies have looked at members of ethnic or sexual minorities or obese individuals [7] without considering stigma against unemployed people with mental health problems. Supporting our hypothesis, individuals who attributed experienced discrimination to mental health problems as well as to unemployment experienced worse job- and help-seeking outcomes.

Our finding that the experience of multiple discrimination is associated with reduced job search self-efficacy is consistent with the notion that the stigma associated with unemployment and mental health problems contributes to long-term unemployment. In a Romanian study job search self-efficacy was negatively associated with anxiety, possibly due to the threatening nature of unemployment and of unsuccessful job search [47]. In our study, unemployment stigma has likely been relevant as it was conducted in Southern Germany, a region currently characterized by a low unemployment rate of about 3% [48]. Under these conditions, the general public may show less understanding for the unemployed, and we could speculate that stigma and discrimination against unemployed individuals might be increased, undermining their confidence to find a job [22].

Stigma-related barriers to treatment were predicted by attributions of discrimination to both unemployment and to mental health problems. This is consistent with the double disadvantage hypothesis that multiple stigma results in additive or cumulative effects [27]. On the one hand people with mental health problems may avoid treatment in order not to be labelled “mentally ill” [17]. On the other hand O´Donnell et al. [30] showed that unemployed participants who experienced higher anticipated stigma because of their unemployment reported increased psychological distress. A new unemployment-related stigmatized identity could lead to withdrawal from support systems [10] that would otherwise help to cope with unemployment and mental health problems.

Participants who attributed discrimination to unemployment and to mental health problems reported more need for treatment and presence of illness than people who attributed discrimination to unemployment. This finding is in line with the double disadvantage hypothesis and results of Grollman [27] that respondents who held more than one disadvantaged status were more likely to experience distress compared to their singly disadvantaged counterparts. Stigma-related stress may be an important mediator of the relationship between discrimination and health among members of multiple minority groups [31, 49]. Vice versa, participants with higher symptom levels may have self-identified as having a mental health problem and therefore may have perceived more need for treatment as well as more illness-related discrimination.

Limitations and future research

Limitations of our study need to be considered. Rather than measuring specific examples of discrimination associated with unemployment or mental health problems, participants rated the extent to which they attributed general everyday discrimination to their unemployment and mental health problems. Due to our sample characteristics we could not examine the role of ethnic minority status. Our cross-sectional data preclude conclusions on causality. The lack of evidence for an interaction of attributions might be related to the fact that not all participants self-identified as having a mental health problem (especially those not receiving mental health care at the time of the study) and not all may have considered unemployment as an important element of their identity (especially those who had been employed until very recently and expected fast reemployment, or those with part-time employment who earned 450 Euros/week or less).

Despite these limitations, our findings highlight the need to consider multiple stigma among unemployed people with mental health problems. Future studies could focus on diverse social structures and conditions to recognize the complex characteristics of stigma, including ethnic minority or migrant status, education and gender. Considering the potential interaction between mental health problems and unemployment, future studies of multiple discrimination should collect qualitative data, e.g. by individual or focus groups interviews.

Implications to reduce multiple discrimination

Whether existing interventions to reduce mental illness stigma can effectively reduce multiple forms of discrimination is a topic for future research. Programs to reduce unemployment-related stigma seem to be lacking. Our results call for interventions to reduce multiple stigma and discrimination against unemployed people with mental health problems on an individual, structural and public level. Because unemployed people with mental health problems can suffer from self-stigma and shame, undermining help-seeking and job search motivation, they should be supported in their coping with mental illness-related as well as unemployment-related stigma. One approach could be Job Club group interventions that increase personal control, self-esteem and job search self-efficacy [50] and offer the opportunity of peer support to cope with stigma.

Because intersectionality refers to the interdependence between social identities and structural inequities [46], there is a need to offer support for people who suffer from multiple stigma such as supported employment which includes employment activities based on individual preferences and needs, integration of employment services into mental health services and personalized benefits planning [12]. Due to the fact that the concept of supported employment is not routinely implemented in the German health care or employment agency systems, policy changes should be considered. Additionally, contact-based interventions [26, 51] could reduce multiple stigma and attitudes and behaviors among members of the general public.

References

Jahoda M, Lazarsfeld PF, Zeisel H (1971) The sociography of an unemployed community, Marienthal. Aldine, Chicago (published in German in 1933)

Frasquilho D, Matos MG, Salonna F, Guerreiro D, Storti CC, Gaspar T, Caldas-de-Almeida JM (2016) Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession. A systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 16:115

Olesen SC, Butterworth P, Leach LS, Kelaher M, Pirkis J (2013) Mental health affects future employment as job loss affects mental health. Findings from a longitudinal population study. BMC Psychiatry 13:144

Olesen SC, Butterworth P, Rodgers B (2012) Is poor mental health a risk factor for retirement? Findings from a longitudinal population survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(5):735–744

Honkonen T, Virtanen M, Ahola K, Kivimäki M, Pirkola S, Isometsä E, Aromaa A, Lönnqvist J (2007) Employment status, mental disorders and service use in the working age population. Scand J Work Environ Health 33(1):29–36

Brand JE (2015) The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annu Rev Sociol 41(1):359–375

Wanberg CR (2012) The individual experience of unemployment. Annu Rev Psychol 63:369–396

Butterworth P, Leach LS, Pirkis J, Kelaher M (2012) Poor mental health influences risk and duration of unemployment. A prospective study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(6):1013–1021

Lamberg T, Virtanen P, Vahtera J, Luukkaala T, Koskenvuo M (2010) Unemployment, depressiveness and disability retirement. A follow-up study of the Finnish HeSSup population sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45(2):259–264

Staiger T, Waldmann T, Rüsch N, Krumm S (2017) Barriers and facilitators of help-seeking among unemployed persons with mental health problems: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 17(1):39

Åhs A, Burell G, Westerling R (2012) Care or not care—that is the question. Predictors of healthcare utilisation in relation to employment status. Int J Behav Med 19(1):29–38

Becker DR, Drake RE (2003) A working life for people with severe mental illness. Oxford Press, New York

Link BG, Phelan JC (2001) Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 27(1):363–385

Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW (2005) Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry 20(8):529–539

Corrigan PW (2004) How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol 59(7):614–625

Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown JSL, Thornicroft G (2015) What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med 45(1):11–27

Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Rüsch N (2009) Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry 8(2):75–81

Ho GC, Shih M, Walters DJ et al. (2011) The stigma of unemployment: When joblessness leads to being jobless. University of California, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7nh039h1. Accessed 24 Mar 2018

Furåker B, Blomsterberg M (2003) Attitudes towards the unemployed. An analysis of Swedish survey data. Int J Soc Welf 12(3):193–203

Maddy LM, Cannon JG, Lichtenberger EJ (2015) The effects of social support on self-esteem, self-efficacy, and job search efficacy in the unemployed. J Employ Couns 52(2):87–95

Albion MJ, Fernie KM, Burton LJ (2005) Individual differences in age and self-efficacy in the unemployed. Austral J Psychol 57(1):11–19

Saks AM, Zikic J, Koen J (2015) Job search self-efficacy. Reconceptualizing the construct and its measurement. J Vocat Behav 86:104–114

Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG (2013) Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health 103(5):813–821

Cole ER (2009) Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol 64(3):170–180

Rosenthal L (2016) Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: an opportunity to promote social justice and equity. Am Psychol 71(6):474–485

Oexle N, Corrigan PW (2018) Understanding mental illness stigma toward persons with multiple stigmatized conditions. Implic Intersect Theory Psychiatr Serv. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700312

Grollman EA (2014) Multiple disadvantaged statuses and health: the role of multiple forms of discrimination. J Health Soc Behav 55(1):3–19

von dem Knesebeck O, Kofahl C, Makowski AC (2017) Differences in depression stigma towards ethnic and socio-economic groups in Germany—exploring the hypothesis of double stigma. J Affect Disord 208:82–86

Hamilton S, Corker E, Weeks C, Williams P, Henderson C, Pinfold V, Rose D, Thornicroft G (2016) Factors associated with experienced discrimination among people using mental health services in England. J Ment Health 25(4):350–358

O’Donnell AT, Corrigan F, Gallagher S (2015) The impact of anticipated stigma on psychological and physical health problems in the unemployed group. Front Psychol 6:1263

Khan M, Ilcisin M, Saxton K (2017) Multifactorial discrimination as a fundamental cause of mental health inequities. Int J Equity Health 16(1):43

Luck-Sikorski C, Schomerus G, Jochum T, Riedel-Heller SG (2018) Layered stigma? Co-occurring depression and obesity in the public eye. J Psychosom Res 106:29–33

Oexle N, Waldmann T, Staiger T, Xu Z, Rüsch N (2018) Mental illness stigma and suicidality. The role of public and individual stigma. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 27(2):169–175

Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Waldmann T, Staiger T, Bahemann A, Oexle N, Wigand M, Becker T (2018) Attitudes toward disclosing a mental health problem and reemployment. A Longitudinal Study. J Nerv Ment Dis 206(5):383–385

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand S-LT, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(2):184–189

Brown RL, Rounds LA (1995) Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wis Med J 94(3):135–140

Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Dickson-Fuhrman E, Daum G, Jaffe J, Jarvik L (2001) Screening for drug and alcohol abuse among older adults using a modified version of the CAGE. Am J Addict 10(4):319–326

Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J, Saxena S, von Korff M, Pull C (2010) Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ 88(11):815–823

Andrews G, Kemp A, Sunderland M, von Korff M, Üstün TB (2009) Normative data for the 12 item WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. PLoS One 4(12):e8343

Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB (1997) Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol 2(3):335–351

van Ryn M, Vinokur AD (1992) How did it work? An examination of the mechanisms through which an intervention for the unemployed promoted job-search behavior. Am J Commun Psychol 20(5):577–597

Choi JN, Price RH, Vinokur AD (2003) Self-efficacy changes in groups. Effects of diversity, leadership, and group climate. J Organ Behav 24(4):357–372

Clement S, Brohan E, Jeffery D, Henderson C, Hatch SL, Thornicroft G (2012) Development and psychometric properties the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) related to people with mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry 12:36

Marks KA, Fastenau PS, Lysaker PH, Bond GR (2000) Self-Appraisal of Illness Questionnaire (SAIQ): relationship to researcher-rated insight and neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 45(3):203–211

Lantz B (2013) The impact of sample non-normality on ANOVA and alternative methods. Br J Math Stat Psychol 66(2):224–244

Kang SK, Bodenhausen GV (2015) Multiple identities in social perception and interaction: challenges and opportunities. Annu Rev Psychol 66:547–574

Rusu A, Chiriac DC, Sălăgean N, Hojbotă AM (2013) Job search self-efficacy as mediator between employment status and symptoms of anxiety. Rom J Appl Psychol 15(2):69–75

Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2017) Statistik/Arbeitsmarktberichterstattung: Der Arbeits-und Ausbildungsmarkt in Deutschland – Monatsbericht [statistics/federal employment market monitoring: The employment and education market in Germany - monthly report].https://m.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/_Anlagen/2017/11/2017-11-30-monatsbericht-ba-november.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1. Accessed 24 Mar 2018

Rüsch N, Heekeren K, Theodoridou A, Müller M, Corrigan PW, Mayer B, Metzler S, Dvorsky D, Walitza S, Rössler W (2015) Stigma as a stressor and transition to schizophrenia after one year among young people at risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res 166(1–3):43–48

Moore THM, Kapur N, Hawton K, Richards A, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D (2017) Interventions to reduce the impact of unemployment and economic hardship on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. Psychol Med 47(6):1062–1084

Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, Koschorke M, Shidhaye R, O’Reilly C, Henderson C (2016) Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet 387(10023):1123–1132

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the German Federal Employment Agency and its Medical Service as well as to joint local agencies and approved local providers for their support with participant recruitment. This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG, RU 1200/3 -1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of Ulm University approved the study (ref. nr. 344/13). All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the committee. Participants received detailed information about the study and provided written informed consent.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Participants provided written informed consent under the condition of confidentiality of their data. Therefore, data cannot be shared publicly.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Staiger, T., Waldmann, T., Oexle, N. et al. Intersections of discrimination due to unemployment and mental health problems: the role of double stigma for job- and help-seeking behaviors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53, 1091–1098 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1535-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1535-9