Abstract

Purpose

We sought to investigate the association between social capital and child behavior problems in Iwate prefecture, Japan, in the aftermath of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake.

Methods

Children and their caregivers were recruited from four nursery schools in coastal areas affected by the tsunami, as well as one in an unaffected inland area (N = 94). We assessed the following via caregiver questionnaire: perceptions of social capital in the community, child behavior problems (Child Behavior Checklist, Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, child’s exposure to trauma (e.g. loss of family members), and caregiver’s mental health (Impact of Event Scale-R for PTSD symptoms; K6 for general mental health). We collected details on trauma exposure by interviewing child participants. Structural equation modeling was used to assess whether the association between social capital and child behavior problems was mediated by caregiver’s mental health status.

Results

Children of caregivers who perceived higher community social capital (trust and mutual aid) showed fewer PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, caregiver’s mental health mediated the association between social trust and child PTSD symptoms. Social capital had no direct impact on child behavior problems.

Conclusions

Community social capital was indirectly associated (via caregiver mental health status) with child behavior problems following exposure to disaster. Community development to boost social capital among caregivers may help to prevent child behavior problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the aftermath of natural disaster, a significant proportion of children exhibit mental health problems, such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, or behavior problems. For example, after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami [1–6], Hurricane Katrina in the USA in 2005 [7–10], and the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China [11–14], 6–28 % of children were reported to suffer from depression or PTSD symptoms. Further, 15–30 % of preschool children who experienced high-intensity trauma during the World Trade Center terrorist attacks, such as witnessing the towers collapse, later showed behavioral symptoms [15]. Research based on data from the Great East Japan Earthquake Follow-up for Children Study showed that 25 % of children had clinically significant behavior problems even two years after the disaster [16].

To address child behavior problems, provision of mental health care by child psychiatrists or psychologists would be optimal; however, clinical care resources are limited, especially after disaster. In this situation, the mobilization of other community-based assets—such as social capital at community level—might be helpful in reducing child behavior problems. ‘Social capital’ at community level refers to resources that individuals can access through their social networks in the community, school, or at work [17], and is measured by indicators such as: (a) levels of social trust in the community, (b) norms of reciprocity and mutual assistance, and (c) the capacity for planned, collective action [18]. This is different from social capital at individual level, which refers is similar to social support [19]. Previous studies have shown that communities with high social capital exert a protective influence on adult mental health after disaster [20, 21], and as parental/caregiver mental health can have a positive influence on child mental health, social capital might also have a protective effect on child behavior problems via parental mental health. Alternatively, community social capital might have a direct effect on child behavior problems; for example, in a community with high levels of trust, children may feel more secure and experience less stress. Thus, we hypothesized that community social capital after a disaster may reduce child behavior problems, directly or indirectly, through parental mental health.

We sought to investigate this hypothesis by assessing child behavior problems, caregiver’s mental health, and social capital among families with young children aged 4–6 years old at the time of the disaster who were affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake (the assessment was implemented 2 years after the disaster). As these children were exposed to the disaster before entering elementary school, the primary caregiver and community may have had an effect on the development of child behavior problems. The purpose of this study is to examine whether social capital after the Great East Japan Earthquake has a direct protective effect on child behavior problems or an indirect effect through caregiver’s mental health status.

Methods

Sample

Four nursery schools within three municipalities affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake in the coastal areas as well as one in an unaffected inland area of Iwate prefecture, Japan, were selected for this study. From September to December 2012, children aged 4–6 years on March 11, 2011 (5–7 years at time of recruitment) (N = 251) were invited to participate through their caregivers, and 80 caregivers (77 mothers and 3 fathers) agreed to join the study. Siblings of the target children were then added to increase the sample size. Finally, 94 children actually participated (i.e. either their caregiver responded to the questionnaire or the child participated in the interview). The Research Ethics Committee at the National Center for Child Health and Development approved this study, including procedure to obtain informed consent from caregiver and assent from children.

Measurements

Child behavior problems were assessed using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [22] and the Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire (SDQ) [23], which were completed by participating caregivers. The CBCL measures behavior problems that are internalized (withdrawn behavior, somatic complaints, anxiety/depression), externalized (rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior), as well as total behavior problems (internalizing and externalizing behavior problems plus social problems, thought problems, and attention problems). Next, sex-standardized T scores from the CBCL among Japanese children were calculated [24]. Of the five SDQ subscales, the following four were used in this study: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer relationship problems. These four subscales were combined and coded as ‘difficult behavior’. Symptoms of PTSD among children were also assessed using a caregiver questionnaire, the Parent Report of the Child’s Reaction to Stress [25], from which 28 items were selected to reduce the burden on respondents.

In conjunction with the assessment of PTSD symptoms, children’s exposure to disaster-related trauma was evaluated via both an interview of the child by child psychiatrists or psychologists, and completion of a questionnaire by caregivers. Exposure to the following traumatic events was assessed at interview based on items developed in a previous study [1]: being separated from parents at the time of the earthquake; death of a close family member; death of other relatives or friends; witnessing tsunami waves, or someone being swept away by the tsunami; exposure to fire, or seeing a dead body. The caregiver questionnaire included questions that assessed exposure to the following traumatic events: loss of a family member, damage to the family home (either completely or partially), staying at a shelter, living in temporary quarters, evacuation to a relative’s house, and separation from a family member. The combined total number of traumatic events was then calculated from the interview and questionnaire data.

Caregiver’s mental health was assessed for PTSD symptoms using the self-reported questionnaire, Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R) [26], and depression/anxiety was assessed using the K6 [27].

Social capital was assessed via a questionnaire to caregivers that explored their perception of cognitive social capital, i.e. social trust and mutual aid, in the community where they lived with their family after the disaster. Social trust was assessed by the following question: “Do you think that people in your neighborhood trust each other?”, with the following 4-point Likert scale response options: “Agree”, “Somewhat agree”, “Somewhat disagree”, and “Disagree”. Mutual aid was assessed by the following question: “Do you think that people in your neighborhood help each other?”, with the same 4-point Likert scale responses.

Analysis

Scores from the CBCL, SDQ, PTSD symptoms assessment, IES-R, K6 and social capital indicators were used as continuous outcomes. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to determine the association between social capital, caregiver’s mental health, PTSD symptoms, and child behavior problems. A conceptual model of the causal association between social capital indicators, caregiver’s mental health, child PTSD symptoms, and child behavior problems was developed based on the following assumptions. We theorized that mutual aid enhances social trust in the community, and that both would be directly associated with caregiver’s mental health and child behavior problems. In addition, we hypothesized that child behavior problems can be induced by PTSD symptoms, which in turn would be determined by the number of traumatic events related to the disaster. The number of traumatic events experienced by the child was hypothesized to be associated with caregiver’s mental health. Further, child age is directly associated with child behavior problems as developmental stages are critical to determining such problems. Maternal mental illness was defined as a latent variable determined by maternal PTSD symptoms (IES-R) and depression/anxiety (K6), and child behavior problems were defined as a latent variable determined by CBCL total behavior problems and SDQ difficult behavior. Stata 13 SE (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample. Ages of children ranged from 4 to 8 years of age, with a mean age of 6 years at the time of study. The sample included slightly more boys (58.5 %) than girls. Clinically significant behavior problems were found in over 25 % of participating children in both the measurement of CBCL total behavior problems (26.6 %) and SDQ difficult behavior (28.7 %). The number of disaster-related traumatic events experienced was 2.1, although 67 % of children did not experience any of these traumatic events. Regarding caregiver’s mental health, 21 % of mothers showed PTSD symptoms on the IES-R, and 19 % showed depression or anxiety on the K6. Mothers perceived social capital after the disaster as high, i.e., more than 70 % responded that social trust or mutual aid was either high or relatively high in the community.

Table 2 shows Spearman’s correlation between child and caregiver’s mental health variables and social capital indicators. As expected, child behavior problems that were assessed by the CBCL and SDQ, PTSD symptoms, and the number of traumatic events were highly positively correlated (p < 0.001). Caregiver’s mental health assessed by the IES-R and K6 were also highly positively correlated (p < 0.001). Moreover, child mental health indicators and caregiver’s mental health indicators were also highly positively correlated (p < 0.001). However, social capital indicators were significantly associated with only caregiver’s mental health, but not for indicators of child behavior problems.

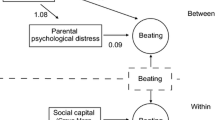

Figure 1 shows the result of SEM for the association between social capital indicators, caregiver’s mental health, child PTSD symptoms, and child behavior problems. The following model was considered: LR test of model, Chi square [19]: 34.8, p = 0.010, RMSEA 0.100; lower limit 0.048; upper limit 0.149; p close 0.057; CFI 0.956. We confirmed the following causal model: higher social trust decreased maternal mental illness (standard coefficient −0.60, p < 0.001), and maternal mental illness was directly associated with child PTSD symptoms (standard coefficient 0.51, p < 0.001), which in turn were associated with child behavior problems (standard coefficient 0.60, p < 0.001). Mutual aid was neither directly associated with maternal mental illness nor child behavior problems, but mutual aid showed a strong association with social trust (standard coefficient 0.90, p < 0.001).

Result of structural equation model for causal association between social capital indicators, caregiver’s mental health, child PTSD symptoms, and child behavior problems. Number shows standard coefficient. † p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001. LR test of model: Chi square [19]: 34.8, p = 0.010, RMSEA 0.100, lower limit 0.048, upper limit 0.149, p close 0.057, CFI 0.956, SRMR 0.057

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report that community social capital can ameliorate child behavior problems following exposure to disaster trauma. This association was mediated by the influence of social capital on improving caregiver’s mental health.

A number of previous studies have reported on the protective influence of community social capital on adult mental health [28, 29], and several have reported on the impact of social capital on adult mental health after disaster [20, 21]. This study is consistent with these previous studies in showing that higher social capital is protective for adult mental health. Possible pathways to improve mental health via higher social capital can be considered in three ways: (1) psychosocial support, such as sharing one’s experience of traumatic events with others, can reduce stress for the adult, (2) the dissemination of health-relevant information though social networks, and (3) better access to professional mental healthcare and services, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, or other public resources.

Moreover, our findings add to the literature by demonstrating that social capital had a collateral influence on child mental health after disaster via their caregiver’s mental health (even though social capital was not directly associated with child mental health). Our findings are consistent with the ecological model developed by Bronfenbrenner [30]. That is, the microsystem (the actors who directly associate with children, such as family, teachers, peers, health workers) directly affects child health; in addition, the mesosystem (interaction between actors, such as the relationship between parents and the child’s teacher) and the macrosystem (community or social environment) also affect child health indirectly through the microsystem. For children, caregiver’s mental health is crucial for their own mental health because in a crisis situation, such as after disaster, younger children depend on caregivers who are closest to them (in most cases, the mother), which evokes the attachment system [31]. Thus, higher social capital is beneficial not only for adult mothers, but also for their children.

This study has several limitations. First, as this study is cross-sectional, we cannot rule out reverse causation. Second, the sample size was limited and was not representative of all children in the affected area after the earthquake. Third, child behavior problems were assessed by the caregiver only. Fourth, social capital before the earthquake might be important, but we did not have information pre-dating the disaster.

Despite these limitations, this study raises several policy implications. First, building social capital is crucial to improve not only adult mental health, but also child behavior problems, and should be a key consideration for policy makers and public health professionals engaged in post-disaster response and reconstruction, Second, future prospective studies that assess the contribution of community social capital to disaster resilience need to incorporate an assessment of collateral effects, i.e. impacts on network members who are socially connected to victims. Third, there is a need for intervention studies that promote the development of social capital in communities.

In conclusion, community social capital is protective for child behavior problems, mediated by their caregiver’s mental health, following exposure to major disaster. Community development activities that boost social capital may be effective in reducing child behavior problems through the improvement of caregiver’s mental health.

References

Thienkrua W, Cardozo BL, Chakkraband ML et al (2006) Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among children in tsunami-affected areas in southern Thailand. JAMA 296(5):549–559. doi:10.1001/jama.296.5.549

Agustini EN, Asniar I, Matsuo H (2011) The prevalence of long-term post-traumatic stress symptoms among adolescents after the tsunami in Aceh. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 18(6):543–549. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01702.x

Piyasil V, Ketuman P, Plubrukarn R et al (2007) Post traumatic stress disorder in children after tsunami disaster in Thailand: 2 years follow-up. J Med Assoc Thai 90(11):2370–2376

Piyasil V, Ketumarn P, Prubrukarn R et al (2008) Psychiatric disorders in children at one year after the tsunami disaster in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 91(Suppl 3):S15–S20

Ularntinon S, Piyasil V, Ketumarn P et al (2008) Assessment of psychopathological consequences in children at 3 years after tsunami disaster. J Med Assoc Thai 91(Suppl 3):S69–S75

Piyasil V, Ketumarn P, Prubrukarn R et al (2011) Post-traumatic stress disorder in children after the tsunami disaster in Thailand: a 5-year follow-up. J Med Assoc Thai 94(Suppl 3):S138–S144

Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH (2008) Reconsideration of harm’s way: onsets and comorbidity patterns of disorders in preschool children and their caregivers following Hurricane Katrina. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 37(3):508–518. doi:10.1080/15374410802148178

Marsee MA (2008) Reactive aggression and posttraumatic stress in adolescents affected by Hurricane Katrina. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 37(3):519–529. doi:10.1080/15374410802148152

Osofsky HJ, Osofsky JD, Kronenberg M, Brennan A, Hansel TC (2009) Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after Hurricane Katrina: predicting the need for mental health services. Am J Orthopsychiatry 79(2):212–220. doi:10.1037/a0016179

McLaughlin KA, Fairbank JA, Gruber MJ et al (2009) Serious emotional disturbance among youths exposed to Hurricane Katrina 2 years postdisaster. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(11):1069–1078. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b76697

Liu M, Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Z, Zhang K, Shen J (2011) Mental health problems among children one-year after Sichuan earthquake in China: a follow-up study. PLoS One 6(2):e14706. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014706

Zhang Z, Ran MS, Li YH et al (2012) Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among adolescents after the Wenchuan earthquake in China. Psychol Med 42(8):1687–1693. doi:10.1017/S0033291711002844

Jia Z, Shi L, Duan G et al (2013) Traumatic experiences and mental health consequences among child survivors of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake: a community-based follow-up study. BMC Public Health 13:104. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-104

Yang R, Xiang YT, Shuai L et al (2013) Executive function in children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder 4 and 12 months after the Sichuan earthquake in China. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12089

Chemtob CM, Nomura Y, Abramovitz RA (2008) Impact of conjoined exposure to the World Trade Center attacks and to other traumatic events on the behavioral problems of preschool children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162(2):126–133. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.36

Fujiwara T, Yagi J, Homma H et al (2014) Clinically significant behavior problems among young children 2 years after the Great East Japan Earthquake. PLoS One 9(10):e109342. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109342

Fujiwara T, Kubzansky LD, Matsumoto K, Kawachi I (2012) The association between oxytocin and social capital. PLoS One 7(12):e52018. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052018

Kawachi I, Berkman LF (2014) Social capital, social cohesion, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM (eds) Soical epidemiology, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 290–319

Kawachi I, Kim D, Coutts A, Subramanian SV (2004) Commentary: reconciling the three accounts of social capital. Int J Epidemiol 33(4):682–690 (discussion 700–4)

Flores EC, Carnero AM, Bayer AM (2014) Social capital and chronic post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of the 2007 earthquake in Pisco, Peru. Soc Sci Med 101:9–17. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.012

Wind TR, Komproe IH (2012) The mechanisms that associate community social capital with post-disaster mental health: a multilevel model. Soc Sci Med 75(9):1715–1720. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.032

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Dept. of Psychiatry, Burlington

Matsuishi T, Nagano M, Araki Y et al (2008) Scale properties of the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): a study of infant and school children in community samples. Brain Dev 30(6):410–415

Itani T, Kanbayashi Y, Nakata Y et al (2001) Standardization of the Japanese version of the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18. Psychiatria et Neurologia Paediatrica Japonica 41:243–252

Fletcher K (1996) Psychometric review of the parent report of child’s reaction to stress. In: Stamm BH (ed) Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Sidran Press, Lutherville, pp 225–227

Weiss DS, Marmar CR (1996) The impact of event scale—revised. In: Wilson J, Keane TM (eds) Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Guilford, New York, pp 399–411

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ et al (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32(6):959–976

De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, Huttly SR (2005) Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 59(8):619–627

Fujiwara T, Kawachi I (2008) A prospective study of individual-level social capital and major depression in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health 62(7):627–633

Bronfenbrenner U (1986) Ecology of the family as a context for human development. Dev Psychol 22(6):723–742

Armstrong KL, Fraser JA, Dadds MR, Morris J (2000) Promoting secure attachment, maternal mood and child health in a vulnerable population: a randomized controlled trial. J Paediatr Child Health 36(6):555–562

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants who contributed to this study. We also thank the child psychiatrists and psychologists who provided extra mental health support to participants when requested during interviews. In addition, we thank the research coordinators who managed the logistics of this study, and Ms. Emma Barber for her editorial assistance. This study is supported by a Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (H24-jisedai-shitei-007). The Great East Japan Earthquake Follow-up for Children Study Team is composed of Ms Mitsuko Miura, Iwate Medical University; Dr Hirokazu Yoshida, Miyagi Prefectural Comprehensive Children’s Center; Dr Yoshiko Yamamoto, Iwaki Meisei University; Ms Noriko Ohshima, Fukushima Gakuin University; Dr Keiichi Funahashi and Ms Mai Kuroda, Saitama Children’s Hospital; Dr Takahiro Hoshino, Musashino Gakuin School; Ms Rie Mizuki, Dr Line Akai, and Dr Yoshiyuki Tachibana, National Center for Child Health and Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Nothing to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yagi, J., Fujiwara, T., Yambe, T. et al. Does social capital reduce child behavior problems? Results from the Great East Japan Earthquake follow-up for Children Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 1117–1123 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1227-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1227-2