Abstract

Aims

To describe the Great Smoky Mountains Study (GSMS).

Methods

GSMS is a longitudinal study of child psychiatric disorders that began in 1992 to look at need for mental health services in a rural area of the USA. Over 20 years it has expanded its range to include developmental epidemiology more generally, not only the development of psychiatric and substance abuse problems but also their correlates and predictors: family and environmental risk, physical development including puberty, stress and stress-related hormones, trauma, the impact of poverty, genetic markers, and epigenetics. Now that participants are in their 30s the focus has shifted to adult outcomes of childhood psychopathology and risk, and early physical, cognitive, and psychological markers of aging.

Results

This paper describes the results from over 11,000 interviews, examples of the study’s contributions to science and policy, and plans for the future.

Conclusions

Longitudinal studies can provide insights that aid in policy planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background: child psychiatric epidemiology

Epidemiologic studies of child psychopathology in the United States began with the work of Macfarlane, Honzik, Lapouse, Monk and others in the 1950s. As Lapouse put it: “…the objectives of epidemiologic investigation are to ascertain the incidence, prevalence, and distribution of mental disorders; to determine the characteristics of this distribution; and, by examining linkages with specific characteristics, to demonstrate or gain clues to etiologic relationships with a view to prevention and control” [1] (p. 1569). Thus, epidemiology has two jobs: to measure the public health burden of disease in the community (“descriptive epidemiology”), and to help to increase understanding of causes of disease (“analytic epidemiology”) [2]. Both types of epidemiology study patterns of disease distribution in time and space [2]. Our work addresses both description and etiology, and it pays particular attention to developmental epidemiology: that is, patterns of distribution across time [3, 4].

Great Smoky Mountains Study (GSMS)

Study design

Eleven contingent counties in the southern Appalachian mountain region of North Carolina (Fig. 1) were chosen as the study site for the Great Smoky Mountains Study (GSMS) because: (1) This sparsely populated area, with its 180,000 inhabitants spread over 12,194 km2, is representative of an understudied section of the United States: the rural areas of the south and southeast; (2) Almost all children attend public schools, which means that school records could be used to provide the initial sampling frame for the study; (3) Half the population live in the only sizable town in the area, while the rest live in the rural areas, providing the opportunity to compare psychiatric disorder and service provision in rural and urban settings; (4) The area contains the Qualla Boundary, a federal reservation that is home to the 8000-strong Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians (EBCI), a community with different traditions of dealing with mental illness and its own mental health service system.

Screening sample

Like several other epidemiologic studies [5–7], the GSMS used a screening-stratified sampling design to maximize 3 study goals within a reasonable budget: (1) to understand the developmental pathways of a large sample of children with a high need for mental health care (case-finding); (2) to estimate the prevalence of disorders and risk factors in the population (prevalence estimation); and (3) to map the identified cases onto the general population (generalizability). A brief screening questionnaire for parents [8] identified children with a high probability of mental health service use, i.e., children with psychiatric symptoms. All children with scores above a cutoff point defined from pilot testing were recruited for the main study. In addition, a 1 in 10 random sample of the remainder were also recruited. Weights inversely proportional to probability of selection were attached to each subject’s data, so that estimates of population prevalence could be made, and all publications on population rates use these weights, which adjust estimates and variances for the design characteristics [9].

The screening sample consisted of 4500 children, 1500 each aged 9, 11, and 13 years at baseline. Nine years was selected as the lowest age for 3 main reasons: (1) rates of professional mental health service use are low in younger children [10]; (2) psychiatric epidemiologic methods for evaluating younger children were not well developed at that time, although major advances have been since then [11–13]; and (3) we were interested in the impact of puberty on the onset of some psychiatric disorders. Of those selected, 80 % (N = 1070) participated. All age-eligible American Indian children (N = 430) were approached, and 350 (81 % participated. Apart from the sampling procedures, data collection and methods were identical for all ethnic groups.

Assessments

The CAPA and related measures

Although there have been questionnaires and questionnaire-style interviews for child psychopathology since the 1950s, we were committed to developing an approach that ensured that symptoms were clinically significant. Building on both theoretical work on developmental psychology [14] and methodological work done in adult psychiatry [15, 16], our goal was to assess psychiatric disorders and concomitant factors reliably and validly in the general population, even in people who have not sought professional help for their problems. Details of our group’s work can be found at http://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/measures. The key instrument is the Child and Adolescent Diagnostic Assessment (CAPA), first developed at the Institute of Psychiatry in London by Adrian Angold, Michael Rutter, and others [17]. Subsequently, we developed comparable measures for preschool children (PAPA [18]) and young adults (YAPA [19]). The goal was an interview that combined strict, fully-structured diagnostic criteria (based on iterations of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)) with procedures that “structured the interviewer’s mind” using a detailed glossary to ensure that symptoms were clinically significant [20].

In addition to most DSM psychiatric disorders, a range of correlates and risk factors were measured, including functional impairment, service use, access, and barriers to care (the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA) [21]), family resources, family psychiatric history, traumatic life events and adversities [22], and the impact on the family of having a child with psychiatric problems [23].

Measures of physical functioning

Another goal of GSMS has been to include measures of physical development and functioning compatible with conducting assessments in participants’ homes. Interviewers were trained by a physical anthropologist (Carol Worthman, Ph.D.). At each interview, participants are weighed and measured, and 10 blood spots are collected using methods developed in Dr. Worthman’s lab [24, 25]. These have so far been used in four sets of analyses: (1)Through age 16 they were assayed for luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS), androstenedione in boys and girls, and estradiol in girls, by means of fluorometric immunoassay methods [26]; (2) Through age 30 they have been assayed for known biomarkers of stress (cholesterol, C-Reactive Protein (CRP), Epstein-Barr virus antibodies (EBV) and DHEA-S) [27]; (3) The samples were genotyped using Illumina Human660W-Quad v1DNA Analysis BeadChips [28] (a pilot study showed that even after more than a decade of storage adequate DNA could be extracted from these samples); (4) Work has begun that capitalizes on the repeated blood samples over development to conduct three within-subject assessments. The goal is to explore potential methylation-related mechanisms underlying the association between childhood adverse experiences and subsequent health risks.

Children also completed a self-report measure of Tanner staging, [29] which provides a good approximation to physical examination for pubertal development, and answered a series of questions on self-perception of developmental status relative to other children and satisfaction with developmental status [30]. In the second and third waves of data collection, parents completed the Childhood (Medical) Conditions section of the National Health Interview Survey Supplement Booklet, [31] which collects basic information about the child’s physical health history.

Study procedures

Interviewers are residents of the area in which the study is taking place. Some, but not all, of the interviewers for the American Indian sample are American Indians. All interviewers have at least bachelor’s-level degrees and received 1 month of training. After training, quality control is maintained through post-interview reviews of each schedule, weekly staff meetings to review audiotapes of randomly selected field interviews, and regular refresher sessions with a child psychiatrist on the team (AA). Participant and one parent were interviewed separately through age 16, participants only thereafter.

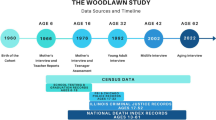

Table 1 shows the percentage of the surviving sample interviewed at each assessment. On average, 80 % of the surviving sample has been interviewed at each assessment, for a total of 11,084 interviews by age 30. By 2015, 37 participants had died; 2.6 % of the original sample and twice as many males as females.

Study findings

More than 100 papers have been published so far from GSMS data. In the remainder of this paper we present three examples of how the prospective, longitudinal structure of the study has been leveraged to explore different themes: (1) the role of puberty in depression; (2) the effect of family income on children’s mental health; and (3) adult outcomes of childhood psychiatric problems.

-

1.

The role of puberty in depression

In childhood, boys and girls have the same rate of depression, but an excess of female cases begins to appear around age 13, and this continues throughout women’s reproductive years [32]. Puberty is a cascade of hormonal events, but also a set of sociological events, as changes in body shape send signals to peers and adults that an individual is ready to take on different roles, and a psychological event as the individual responds to society’s changing expectations. In GSMS hormonal, morphological, and psychosocial data were collected at each wave through age 16, and analyzed to test the “patterns in time” that lead to the gender imbalance in depression.

With parental permission, self-ratings of pubertal morphological status based on the Tanner staging system [33] were performed with the aid of schematic drawings of secondary sexual characteristics (breasts and pubic hair) [32]. Hormone samples were obtained at the beginning of the interview session, as follows. Two finger-prick samples were collected at 20-min intervals, applied to specially prepared paper, dried, and stored at −30 °C. FSH and LH were measured using modifications of commercially available fluoroimmunometric kits for assay of these hormones in serum or plasma (DELFIA; Wallac, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Testosterone (T) and oestradiol (E2) assays are modifications of commercially available serum/plasma radioimmunoassay kits (Binax, South Portland, ME; Pantex, Santa Monica, CA; DSL, Webster, TX, respectively) [34]. Previous work on effects of pubertal status in girls [35] indicated that the relationship between maturation (Tanner stage) and depression was not linear, but better described by distinguishing between stages I–II and stages III–V.

Results

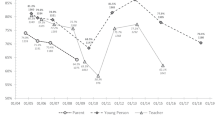

The inclusion of either testosterone or estradiol in the models caused the Odds Ratio for Tanner stage to fall substantially to non-significant levels. When both were included together with Tanner stage, their effects remained significant while the OR for Tanner stage fell still further. The effects of testosterone and estradiol with Tanner stage removed from the model remained almost unchanged. As Fig. 2 shows, the relationship between T/E and depression was not linear; girls in the highest quintiles of T/E exposure had the highest rates of depression.

Making use of both repeated assessments over time and multiple ways of measuring puberty, we were able to show that the gonadal hormones drove the increase in risk for depression experienced by girls entering puberty. Clearly, high T/E alone cannot cause depression or all women would be depressed when T/E peaks during their menstrual cycle. There seems to be something special about adolescent female depression; further analyses [36] showed that low birth weight was a serious risk factor for adolescent depression in girls, but not boys.

-

2.

Impact of a family income supplement: a natural experiment [37]

Although it is rarely possible to conduct randomized controlled trials in epidemiologic studies, it is sometimes possible to allocate groups—classrooms, schools, towns, or other communities—randomly to treatment and control conditions, making the assumption that the estimate of the average treatment effect will be relatively unbiased by site differences: what is called a “natural experiment” [2]. Since 1996, when a casino was opened on the Cherokee reservation, a proportion of the profits (around $4000 a year) has been distributed equally to every enrolled member of the Tribe, without distinction (The funds for children are held by the Tribal administration until they graduate from high school, or reach age 21). Non-Indian youth in the surrounding counties received no comparable income supplement, so we could compare psychiatric symptoms of children with and without the income supplement, without worrying about the possibility that the increased income was in some way connected to family or individual characteristics. We examined the average number of DSM-IV emotional and behavioral psychiatric symptoms in Anglo and American Indian children in the 4 years before and 4 years after the casino opened.

Results

In Indian families, poverty increased between 1993 and 1995, then fell by half between 1996 and 2000; there was no decrease in Anglo families. Among Indian families, 14.4 % moved out of poverty, 53.2 % remained poor, and 32.4 % were never poor. Proportions for Anglo families were 10.3, 20.2, and 69.5 % respectively.

The significant negative correlation between family income and number of symptoms (r = −.05, p < .001) was similar in both Indian and Anglo children. Figure 3 shows how the mean annual score of Indian children’s psychiatric symptoms differed by family income.

An income supplement that moved families out of poverty was followed by a marked improvement in behavioral symptoms over the next 4 years. A similar pattern could be seen in Anglos, but this could have been the result of more intelligent or hard-working families moving out of poverty. The “natural experiment” enabled us to control for such potential biases.

Further analyses in early adulthood [38] showed that number of years in the family home predicted lower rates of any adult psychiatric disorder, specifically of any substance use disorder (SUD). Main effects of race were not significant, but planned comparisons among the 3 age-cohorts showed that the youngest Indian cohort had significantly fewer diagnoses than either of the older cohorts, between whom there were no differences. The youngest Indians also had fewer disorders than the youngest non-Indians. The youngest Indians were significantly less likely to report delinquent friends in adulthood. The impact of the intervention fell to a non-significant level when the model controlled for delinquent adult friends, suggesting a mediational effect [39]. Similar results were seen when the youngest Indians were compared with the youngest Non-Indians. Family supervision, which had mediated the effect of the income supplement in adolescence, [40] did not extend its influence into adulthood. Material hardship did not mediate the intervention effect.

-

3.

Adult functional outcomes of common childhood psychiatric problems

One longstanding aim of the study was to understand risk for and development of common childhood disorders. Unlike many chronic physical health problems, most psychiatric disorders are first diagnosed in childhood [41–43], and can affect individuals into adulthood. With the GSMS participants now approaching their 30 s, it is reasonable to ask whether common childhood disorders have adversely affected functioning during the transition to adulthood. Studying only children meeting full criteria for psychiatric disorders, however, may severely underestimate this burden. Subthreshold problems do not meet full diagnostic criteria, but often are significantly impairing [44, 45]. A complete understanding of the long-term burden of childhood psychiatric problems must include such subthreshold cases.

Childhood psychiatric functioning was measured in 6674 observations of the participants between ages 9 and 16. Participants were coded as psychiatric cases if they met DSM-IV criteria for a common childhood psychiatric disorder (anxiety disorder, mood disorder, ADHD, conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder) at any assessment. If they never met full criteria for a psychiatric disorder but displayed significant psychosocial impairment secondary to psychiatric symptoms, they were coded as subthreshold cases [42, 44]. Remaining subjects never met criteria for either a psychiatric disorder or symptomatic impairment (noncases).

In young adulthood (3215 observations of 1273 subjects at ages 19, 21, and 24–26) adverse adult outcomes were assessed, to identify a broad range of outcomes that that typically impede functioning for an extended period of time across many areas of daily life. We defined four domains: health (e.g., multiple psychiatric problems, suicidality, life-threatening illness), legal (e.g., felony charge, incarceration), financial (e.g., high school dropout, being fired from multiple jobs) and social (e.g., teen parenthood, lack of familial and peer social support).

Six out of 10 of those who met criteria for a common childhood psychiatric disorder reported an adverse outcome, compared with only about 1 in 5 individuals without a history of childhood psychiatric diagnoses. Participants with a childhood disorder had 6 times higher odds of at least one adverse adult outcome compared with those with no history of psychiatric problems and 9 times higher odds of 2 or more such indicators (Fig. 4). These associations persisted after statistically controlling for childhood psychosocial hardships and adult psychiatric problems. Risk, however, was not limited to those with a diagnosis: participants with subthreshold psychiatric problems had 3 times higher odds of adult adverse outcomes and 5 time higher odds of 2 or more outcomes, and here too risk persisted after controlling for adult psychopathology.

The important finding here was that childhood mental illness predicted poor adult functioning even after accounting for childhood psychosocial adversities, such as maltreatment, that have long been linked with both childhood psychiatric disorder and disrupted development (e.g., [46]). If the goal of public health efforts is to increase opportunity and optimal outcomes, and to reduce distress, then there may be no better target than the reduction of childhood distress—at both clinical and subthreshold levels.

Conclusions: the future

These three snapshots show the kind of progress that can be made using epidemiologic methods if we incorporate methods designed to move from “description” towards causal analysis. All three analyses have had an impact in the world of public policy, with newspaper and TV discussions and testimony before a US Senate committee. For us, the take-home message from this and the many other analyses of GSMS data is the importance, for both affected individuals and national health, of identifying and treating children early in life.

As the participants have aged, the research team’s thinking has also progressed. The past 20 years of research have abolished in our minds any boundary between “child” and “adult” psychopathology, and have also broken down barriers between medical, psychiatric, and cognitive functioning. Most psychiatric disorders are first diagnosed in childhood [41–43]. On the one hand, this allows such disorders and their sequelae to affect the entire lifespan; indeed, the 2010 Global Burden of Disease analyses [45] found that neuropsychiatric disorders in youth ages 10–24 were the leading cause of disease burden in high-income countries [47]. We propose to leverage the longitudinal data already collected to understand more about the links between early mental health functioning and later health.

The next phase of GSMS will also focus on “patterns in time” that predict early aging. In addition to our psychiatric assessments, we shall test for early decline in cognitive and physical functioning using a cognitive battery, sphygmomanometry, and spirometry. We will use interviews and biological markers to test for psychosocial and biological processes that might biologically embed the effects of early psychopathology. Work is also in progress using the repeated blood samples to study the impact of traumatic life events on changes in methylation across time. We are endlessly grateful to the study participants who have lived what we only measure.

References

Lapouse R (1957) Removing some roadblocks to mental health research. Am J Public Health Nations Health 47(12):1569

Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H (1982) Epidemiologic research: principles and quantitative methods. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York

Kellam SG, Werthamer-Larsson L (1986) Developmental epidemiology: a basis for prevention. In: Kessler M, Goldston SE (eds) A decade of progress in primary prevention. University Press of New England, Hanover, NH, pp 154–180

Costello EJ, Angold A (2000) Developmental epidemiology: a framework for developmental psychopathology. In: Sameroff A, Lewis M, Miller S (eds) Handbook of developmental psychopathology. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, pp 57–73

Dohrenwend BP et al (1992) Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science 255(Feb. 21):946–952

Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K (1970) Education, health, and behaviour. Longman, London

Bird HR et al (1988) Estimates of the prevalence of childhood maladjustment in a community survey in Puerto Rico: the use of combined measures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 45:1120–1126

Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS (1981) Behavorial problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged four through sixteen. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 46:1–82

Shrout PE, Skodol AE, Dohrenwend BP (1985) A two-stage approach for case identification and diagnosis: First stage instruments. In: Presented at the 75th Annual Meeting of the American Psychopathological Association, New York City. No Journal Found, March 1

U.S. Congress and Office of Technology Assessment (1991) Mental health problems: prevention and services, in adolescent health: volume II: background and the effectiveness of selected prevention and treatment services. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, p 433–496

Costello AJ et al (1984) Development and testing of the NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children in a clinic population: final report (contract no. RFP-DB-81-0027). NIMH Center for Epidemiologic Studies, Rockville

Breton J-J et al (1995) Do children aged 9 to 11 years understand the DISC version 2.25 questions? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:946–956

Franz L et al (2013) Preschool anxiety disorders in pediatric primary care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(12):1294–1303

Rutter M (2013) Developmental psychopathology: a paradigm shift or just a relabeling? Dev Psychopathol 25(4pt2):1201

Wing JK, Cooper JE, Sartorius N (eds) (1974) The measurement and classification of psychiatric symptoms: an instruction manual for the present state examination and CATEGO programme. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Robins LN et al (1981) National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 38:381–389

Angold A (2002) Diagnostic interviews with parents and children. In: Rutter M, Taylor E (eds) Child and adolescent psychiatry: modern approaches. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, pp 32–51

Egger HL, Angold A (2004) The preschool age psychiatric assessment (PAPA): a structured parent interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in preschool children. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A (eds) Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental assessment. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 223–243

Angold A, Cox A, Prendergast M, Rutter M, Simonoff E, Costello E, Ascher B (1999) The young adult psychiatric assessment (YAPA). Duke University Medical Center, Durham (Unpublished)

Angold A, Cox A, Prendergast M, Rutter M, Simonoff E (1995) Glossary for the child and adoelscent assessment. Duke University Medical Center, Durham (Unpublished)

Farmer EMZ et al (1994) Reliability of self-reported service use: test–retest consistency of children’s responses to the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA). J Child Fam Stud 3(3):307–325

Costello EJ et al (1998) Life events and post-traumatic stress: the development of a new measure for children and adolescents. Psychol Med 28:1275–1288

Angold A et al (1998) Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health 88:75–80

McDade TW, Williams S, Snodgrass JJ (2007) What a drop can do: dried blood spots as a minimally invasive method for integrating biomarkers into population-based research. Demography 44(4):899–925

McDade T, Angold A, Costello EJ, Stallings JF, Worthman CM (1995) Physiologic bases of individual variation in pubertal timing and progression: report from the great smoky mountains study. Am J Phys Anthropol Suppl. 20:148

Worthman CM, Stallings JF (1994) Measurement of gonadotropins in dried blood spots. Clin Chem 40:448–453

Worthman CM, Costello EJ (2009) Tracking biocultural pathways in population health: the value of biomarkers. Ann Hum Biol 36(3):281–297

Costello EJ, Eaves L, Sullivan P, Kennedy M, Conway K, Adkins DE, Angold A, Clark SL, Erkanli A, McClay JL (2013) Genes, environments, and developmental research: methods for a multi-site study of early substance abuse. Twin Res Hum Genet 16:505–515

Dorn LD et al (1990) Perceptions of puberty: adolescent, parent, and health care personnel. Dev Psychopathol 26(2):322–329

Petersen AC (1985) Pubertal development as a cause of disturbance: myths, realities, and unanswered questions. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr 111(2):205–232

U.S. Public Health Service (1988) National Health Interview Survey: supplement booklet. U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC

Angold A, Costello EJ (2006) Puberty and depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 15:919–937

Tanner JM (1962) Growth at adolescence: with a general consideration of the effects of hereditary and environmental factors upon growth and maturation from birth to maturity. Vol. Second Edition, Fifth Printing. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford

Worthman CM, Stallings JF (1997) Hormone measures in finger-prick blood spot samples: new field methods for reproductive endocrinology. Am J Phys Anthropol 103(1):1–21

Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman CM (1998) Puberty and depression: the roles of age, pubertal status, and pubertal timing. Psychol Med 28:51–61

Costello EJ et al (2007) Prediction from low birth weight to female adolescent depression: a test of competing hypotheses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:338–344

Costello EJ et al (2003) Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. JAMA 290(15):2023–2029

Costello EJ (2010) Family income supplements and development of psychiatric and substance use disorders among an american indian population—reply. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 304(9):963

Huang B et al (2004) Statistical assessment of mediational effects for logistic mediational models. Stat Med 23:2713–2728

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Kim-Cohen J et al (2003) Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:709–717

Copeland W et al (2011) Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders by young adulthood: a prospective cohort analysis from the great smoky mountains study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50(3):252–261

Kessler RC et al (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6):593–602

Angold A et al (1999) Impaired but undiagnosed. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:129–137

Lewinsohn PM et al (2004) The prevalence of comorbidity of subthreshold psychiatric conditions. Psychol Med 34:613–622

Herrenkohl EC et al (1995) Risk factors for behavioral dysfunction: the relative impact of maltreatment, SES, physical health problems, cognitive ability, and quality of parent-child interaction. Child Abuse Negl 19(2):191–203

Harhay MO, King CH (2012) Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years. Lancet 379(9810):27–28

Acknowledgments

The work presented here was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH080230, MH63970, MH63671, MH48085, MH075766, MH094605), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/MH11301, DA011301, DA016977, DA011301, DA036523), NARSAD (Early Career Award to WEC and Distinguished Investigator Award to EJC), and the William T Grant Foundation (EJC and AA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Costello, E.J., Copeland, W. & Angold, A. The Great Smoky Mountains Study: developmental epidemiology in the southeastern United States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 639–646 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1168-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1168-1