Abstract

Purpose

India has the highest absolute number of maternal deaths, preterm birth cases, and under-5 mortality in the world, as well as high domestic violence (DV) rates. We sought to examine the impact of DV and its psychosocial correlates on pregnancy and birth outcomes.

Methods

Women seeking antenatal care in Tamil Nadu, South India (N = 150) were assessed during pregnancy, and birth outcomes were abstracted from medical records after the babies were born.

Results

We found that psychological abuse (OR 3.9; 95 % CI 1.19–12.82) and mild or greater depressive symptoms (OR 3.3; 95 % CI 0.99–11.17) were significantly associated with increased risk of preterm birth. Physical abuse was also associated with increased risk of preterm birth, but this was not statistically significant (OR 1.9; 95 % CI 0.59–6.19). In each of the above adjusted models, low maternal education was associated with increased risk of preterm birth, in the analysis with depressive symptoms OR 0.18, CI 0.04–0.86 and in the analyses with psychological abuse OR 0.19, CI 0.04–0.91.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that future research should focus on understanding the psychosocial antecedents to preterm birth, to better target interventions and improve maternal child health in limited resource settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

India has the highest absolute number of maternal deaths in the world, accounting for 19 % of global maternal deaths [1]. India also has the highest number of live births in the world at 27.2 million and the highest absolute number of preterm births in the world (approximately 3.5 million; defined as an infant born at ≤37 weeks gestation), accounting for 24 % of global preterm deliveries [2]. India’s rate of preterm birth is 13 %, more than double the rate found in European countries for spontaneous preterm birth and the leading cause of premature death in India [3, 4]. Despite many known causes of preterm birth, precise mechanisms have been difficult to identify [5]. This paper examines psychosocial determinants of preterm birth. In particular, we explore domestic violence and its consequences as one possible contributor to high maternal and child morbidity and mortality rates, as women in India face extreme risk of domestic violence.

Domestic violence against women ranged from 31 to 59.5 % in two multisite studies conducted in India [6–8], dramatically higher than the 27.4 % reported in a general sample of Australian women [9]. In neighboring Pakistan and Bangladesh, these rates were 38 and 52 % for physical violence, respectively [10, 11]. In India, domestic violence can be perpetrated in the household not only by marital partners but also by extended family members. Women in India experience bruises, burns, and poisoning as a consequence of this violence [12], and younger women are also vulnerable to being sold into sex slavery [13]. ‘Fire-related deaths in India are highest among women in their reproductive years (between the ages of 15 and 34), and are often associated with domestic violence [14]. For pregnant women, domestic violence rates are much lower at 7 % in India and 6 % in the United States [15, 16], but still unacceptably high. Disturbingly, although there are strict laws against knowing the gender of the fetus, pregnant women in India are more vulnerable to domestic violence if the fetus is known or thought to be female [17].

Domestic violence has been associated with depressive and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (PTSD) among pregnant, as well as non-pregnant, women in India [15, 18], and studies within and outside of India have demonstrated a connection between domestic violence, common mental disorders (e.g., depression, PTSD), and poor birth outcomes [19, 20]. A meta-analysis of international studies associated antenatal depression with preterm birth and low birth weight, and found that the association of depression with birth outcomes was more pronounced among women from limited resource settings [21]. In India, maternal anxiety and depression were associated with low birth weight in Goa [20]. Moreover, a review of studies conducted in India associated domestic violence with a more than twofold increase in risk of neonatal death [22]. Despite these findings, studies in India have not examined associations between domestic violence, its correlates, and consequences for preterm birth.

In the present study, we sought to examine the effects of domestic violence and its psychological consequences, such as depressive and PTSD symptoms, on pregnancy and birth outcomes. The studies reviewed above examined head circumference, gestational age/preterm birth, and birth weight, and thus we included these factors in our study [17, 20, 23]. In addition, in order to evaluate potential mechanisms for links between maternal mental health and birth outcomes, we examined cesarean section rates and pregnancy complications. We hypothesized that domestic violence, depressive symptoms, and PTSD symptoms would be associated with increased risk for adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes.

Methods

Participants and setting

Our eligibility criteria were as follows: women were included if they were over 18 years of age, Tamil speaking, in their second or third trimester of pregnancy, and seeking care at antenatal clinics in the cities of Vellore and Chennai, both in Tamil Nadu, India. The Vellore clinic is part of a private medical college hospital located in a semi-urban setting, while the Chennai clinic is part of a public medical college hospital in an urban setting. We recruited women from these two sites to enable us to examine public/private hospital differences.

In order to access eligible participants, the research staff gave physicians and nurses in the two facilities an overview of the study and we obtained their permission to have our research assistants approach expectant mothers as they stood in the queue waiting to see the physician. The research assistants asked mothers in the queue if they were in their 2nd or 3rd trimester, their age, and primary language spoken. If eligible, their willingness to participate in an interview was ascertained.

Procedures

Data collection took place across a 9 month time frame. Study procedures were implemented by trained, female research assistants conversant in both Tamil and English. One research assistant was based at each site. Patients who were interested in participating in the study then met with the research assistant who explained study procedures in detail and obtained informed consent (by signature or thumb print), including permission to access medical records to abstract birth outcomes data. The research assistant then administered the battery of questionnaires as an interview. After the women delivered (approximately 2–3 months post-assessment), the research assistants abstracted birth outcomes information from the medical record onto a standard form. All interviews were conducted in the local language of Tamil. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the public and private hospital Institutional Review Boards in India and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Although our study did not need to use the safety protocol, we were prepared to provide immediate physician intervention if participants related their lives were in danger from ongoing physical or sexual violence.

Measures

We obtained socio-demographic information from participants, including maternal age; marital status (married, separated, widowed, divorced); level of education (dichotomously collapsed as “none to 12th standard”, “above 12th standard,” this cutoff defined such that approximately half of the participants to fall into each category); living situation (nuclear, extended); employment status (employed, not employed); and average monthly household income. We also assessed women’s experience of domestic violence, depression and PTSD in individual interviews with participants. We translated all interview questionnaires into Tamil and then back-translated the questions into English to ensure the original meanings of the items were preserved (with the exception of the depression measure, which was already validated in the local context).

Domestic violence

We assessed lifetime history of psychological, physical, or sexual abuse asking about specific behaviors and defining domestic violence broadly to fit the Indian context, in which violence is often perpetrated by extended family members as well as by the spouse. The questions, adapted from the India SAFE study questionnaire [6], prompting participants to refer to experiences from their natal or marital family members. To measure psychological abuse we asked, “Has anyone ever insulted you, frightened you or someone you love, did something that made you feel afraid without touching you, or abandoned you?” If the participant acknowledged experiencing such abuse, she was asked to list the specific individual(s) in the marital or natal family or neighborhood responsible for it. Similarly, to measure physical abuse we asked, “Has anyone ever slapped, hit, kicked or beaten you?” And for sexual abuse we asked, “Has anyone ever forced you to have sex against your will?” Here again, those who acknowledged such experiences were asked to list the specific individual from the marital or natal family or neighborhood responsible for perpetrating the abuse. Each question was rated along a 3-point scale (No, Yes, Refused).

Psychosocial: depressive symptoms

We used the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item tool (PHQ-9), previously used to assess peripartum depressive symptoms [24], to assess severity of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The tool comes from the broader set of questionnaires called the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) [25, 26] and we used a Tamil language version of the scale, which has been validated for the South Indian context [27–29]. The scale asks participants to indicate if they have been bothered by a list of problems, such as “Little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “Feeling tired or having little energy” and “Poor appetite or overeating.” We administered the tool as an interview and asked participants to respond by selecting one of four Likert scale options, ranging from “not at all, or 0” to “nearly every day, or 3”. In order to accommodate anticipated poor literacy among participants, we depicted response categories on a sheet with four numbers representing the response options, which were explained in Tamil. Standard scores on the PHQ-9 range from 0 to 27, and we categorized depressive symptoms as being ‘not clinically significant’ (total scores of <4) to ‘clinically significant’ (total scores of ≥5; considered mild or greater depressive symptoms), following standard PHQ-9 scoring guidelines of clinically significant symptoms being mild, moderate, or severe [30].

Psychosocial: posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms

Participants also completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist-civilian version (PCL-C), administered as an interview [31]. The scale contains 17 items, and asks participants if they have had experiences such as “feeling distant or cut off from other people” or “repeated, disturbing dreams of a stressful experience from the past”. The recall period for this scale is 1 month. Participants selected one of four Likert scale options, ranging from “not at all, or 1” to “extremely, or 5”. Again, we listed response choices on a sheet of paper with numbers representing the response options, and participants were asked to point to the number representing their response. We calculated PTSD symptom scores and used the accepted total score cutoff of 30 (out of 85 possible) to define ‘clinically significant’ symptoms [31, 32]. The PCL has been used in the South Indian context in Kannada, another Dravidian language spoken in a neighboring state with a similar cultural context [15, 33]. We translated the tool into Tamil and then back-translated it into English to ensure the original meaning was preserved.

Pregnancy and birth outcomes

From the medical records, we recorded whether the women had evidence of gestational diabetes or pre-eclampsia, which were collapsed into one category called “pregnancy complications”. We also tracked whether a caesarian section had been performed. Lastly, also from the medical record, we recorded problems at birth (e.g., birth asphyxia, respiratory problems), stillbirth, gestational age at birth (in weeks), birth weight, and head circumference at birth (in cm). We used the World Health Organization definition of preterm birth, defined as an infant born at ≤37 weeks gestation.

Statistical analyses

Using a medium effect size of 0.15 and a significance level (alpha) set at 0.05, we estimated that we would have at least 80 % power to detect a clinically important difference in scores with a sample size of 68. Sample size calculations were conducted with “G power” software. We anticipated difficulty collecting birth outcomes data for all participants and estimated that approximately 10 % of cases would have missing birth outcomes data and thus enrolled 75 participants at each site to account for potential missing data and to be able to examine variables with and across sites.

In addition to descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha calculations on the PHQ-9 and PCL, we calculated bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients to investigate relationships between variables of interest (age, education, psychological abuse; physical abuse; clinically significant depressive symptoms; clinically significant PTSD symptoms; birth weight, head circumference, problems at birth, stillbirth, cesarean section, pregnancy complications). Statistically significant (p < 0.05) bivariate correlations guided our subsequent analyses, and we included significant variables in subsequent multivariable regression analyses. We then conducted multiple linear and logistic regression analyses with the socio-demographic, domestic violence, and psychosocial variables as independent variables and birth outcomes as dependent variables, separately for each dependent variable.

Given the strong relationships between psychological abuse, clinically significant depressive symptoms, and our particular interest in physical abuse, we conducted three separate logistic regression analyses to address multicollinearity. In the 1st analysis, preterm birth was the dependent variable and psychological abuse was the independent variable. We adjusted for maternal education, as it was the only socio-demographic variable associated with preterm birth. In the 2nd analysis, we used physical abuse as the independent variable, keeping all else the same. In the 3rd analysis, we used clinically significant depressive symptoms as the independent variable, keeping all else the same.

Results

Socio-demographic information

One hundred and fifty women participated in the present study, 75 from the Vellore private hospital and 75 from the Chennai public hospital. The flow of recruitment, refusals, and loss to follow up is depicted in Fig. 1. The mean age of participants was 24.8 years (SE = 4.1). All of the women were married, and 24.7 % lived within a nuclear family setting while 75.3 % lived with extended family. In terms of education, 59 % had “none to 12th standard” level education and 41 % had an “above 12th standard” level of education. Nine percent of the women were employed outside of the home, and the reported average monthly household income was approximately Rupees 10,000 (approximately $161). Table 1 lists means and frequencies for the socio-demographic variables for all participants, separated by public and private hospital site. Significant site differences existed with respect to participants’ ages, education levels, living situations, and monthly household incomes. The women in the private hospital setting were significantly older, had more years of education, had higher household incomes, were more likely to be employed, and were more likely to live in extended family settings than women in the public hospital setting.

Domestic violence

Twenty-four percent of the women reported any experience of psychological abuse, and 29 % of the women reported any experience of physical abuse (Table 2). No women reported an experience of sexual abuse. Significantly more women at the public hospital setting experienced both types of abuse than did women attending the private hospital.

Psychosocial variables

Twenty-one percent of women reported clinically significant depressive symptoms (total scores of ≥5 out of 27) and 19 % reported clinically significant PTSD symptoms (total scores of ≥30 out of 85), but there were no differences in these rates by site (See Table 2 for full details). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.83 for the PHQ-9 and 0.91 for the PCL.

Pregnancy and birth outcomes

Of the 150 women who completed the study measures, 119 of them gave birth in the same institution in which they received antenatal care. Thus, we had a 21 % loss to follow-up (Fig. 1). Twelve percent of these participants had pregnancy complications (i.e., gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia), 14.3 % of the women had a cesarean section, 2.7 % of the newborns had problems at birth, and 2.7 % were stillborn. Some statistically significant site differences included more women having pregnancy complications and caesarean sections in the private hospital setting than in the public hospital setting. Mean gestational age at birth for the newborns was 38.3 weeks (SD = 2.2), mean birth weight was 2.9 kg (SD = 0.5), and mean head circumference was 33.4 cm (SD = 2.0). Approximately 12 % of the women had babies that were born preterm. No significant differences existed across sites for these newborn statistics. Table 3 depicts the birth outcomes data overall and by each site.

Bivariate correlations

In addition to the site differences described above, we performed bivariate correlational analyses on all variables of interest to guide our subsequent regression analyses. We report below when a statistically significant correlation existed between socio-demographic, psychosocial, or pregnancy/birth outcomes variable. Among the socio-demographic variables, we found a statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05) between lower levels of maternal education and preterm birth. In terms of domestic violence and psychosocial variables, we found that psychological abuse and clinically significant depressive symptoms had statistically significant correlations with preterm birth. In addition, clinically significant depressive symptoms and psychological abuse were highly correlated with one another (p < 0.01). Hospital type (public vs. private), physical abuse, and PTSD symptoms were not associated with preterm birth. Since physical abuse was a primary variable of interest, we included it in subsequent multivariable analyses. We did not include PTSD symptoms or hospital type in the regression analyses.

Regressions

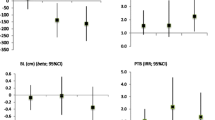

We found that psychological abuse was significantly associated with risk of preterm birth, while adjusting for mother’s educational level. The odds of preterm birth for a mother who reported having experienced psychological abuse were approximately 4 times greater than for a mother who had no experience of psychological abuse (OR 3.9; 95 % CI 1.19–12.82). In the second regression, the odds of preterm birth for a mother who reported physical abuse were non-significant, but approximately 2 times greater than for a mother who had no experience of physical abuse (OR 1.92; 95 % CI 0.59–6.19). Finally, we found the trend that clinically significant depressive symptoms were associated with preterm birth, while adjusting for mother’s educational level. Mothers who reported clinically significant depressive symptoms were about 3 times more likely to have a preterm delivery than a mother who reported no symptoms(OR 3.3; 95 % CI 0.99–11.17). Higher maternal education remained significantly associated with reduced risk of preterm birth (in the analysis with depressive symptoms OR 0.18, CI 0.04–0.86 and in the analyses with psychological abuse OR 0.19, CI 0.04–0.91). Figure 2 depicts results from these analyses in a forest plot.

Discussion

Our study found that both psychological abuse and clinically significant depressive symptoms were associated with preterm birth. As well, we found that maternal depressive symptoms and experience of psychological abuse were strongly associated with each other. Although the association between physical abuse and preterm birth was not statistically significant, we did find a twofold greater chance of preterm birth among women who had experienced physical abuse compared to women who had not. In addition, we also found an association between lower levels of maternal education (high school or below) and preterm birth. This finding is consistent with Gakidou and colleagues’ international study of maternal education and its association with child mortality, in which the investigators found that decreases in child mortality could be explained by increases in maternal education [34].

The association between physical abuse and preterm birth, and PTSD and preterm birth, were not statistically significant. However, we observed that rates of lifetime physical abuse were similar to previously published rates among pregnant women in India [6, 7]. Women from the public hospital had dramatically higher rates of physical and psychological abuse than women from the private hospital. Furthermore, we found that the rate of clinical significant PTSD symptoms among pregnant women in our study was 19.3 %. No general adult PTSD prevalence studies have been conducted with women India; rates of PTSD among women in the United States are around 9.7 % [35].

This strong connection between psychosocial stressors and preterm birth in India is important, given that India has the world’s highest absolute numbers of maternal mortality, preterm birth, and under-five child mortality in the world; and preterm birth is a major cause of under-five child mortality globally [36]. Adding to the significance of this finding, researchers that were part of the Indian national ‘Million Death Study’ found that prematurity and low birth weight account for 78 % of all neonatal deaths in the country [37]. Further, preterm birth has been associated with intellectual disabilities, autism, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy [38], all of which cause a significant burden to India’s Health Sector. Our findings lend evidence to the notion that one avenue toward reducing poor maternal and child health in India may be to focus on educational and behavioral interventions that will both empower women and improve health.

Interventions targeted toward reducing the rate of psychological abuse within families also appear indicated as a means of improving women’s health and reducing infant prematurity. Our findings around psychological abuse can be related to Patel’s discussion of the term ‘gender disadvantage,’ in which women have little decision-making autonomy and poor family support which can lead high levels of depression and anxiety disorders [19]. Patel’s study, like ours, shows that the poor treatment of women in the home is associated with negative mental health outcomes.

To date, much of the emphasis on domestic violence focuses on physical and sexual abuse. Our findings demonstrate that psychological abuse also has significant detrimental effects on maternal and child health and should be included in intervention targets. Given that most current policy initiatives focus predominantly on physical abuse, psychological abuse may be missed through these initiatives.

It is also important to conduct further research to understand specific pathways by which domestic violence may lead to preterm birth. Some of the mechanisms involved may be due to injuries or other direct functions of violence. Certain studies have posited that such associations with preterm birth may be due to increases in stress hormones [39, 40]. Under-nutrition in mothers and other environmental factors may also contribute to the larger picture of preterm birth in India [41]. Our findings regarding psychological and physical abuse lends support to the idea that the impact of environmental stress itself contributes to adverse birth outcomes.

Our study had several limitations. Because this was a pilot study, our sample size was small and we collected data on a limited number of variables. We did not collect information on parity. Future studies would benefit from collecting comprehensive data from large samples of mothers. Second, our study had a higher percentage of women than anticipated who did not deliver in the clinics where they received antenatal care (21 %), which excluded women who may have delivered at home or in institutions near to their natal families. This may have over or under-estimated the relationships between psychosocial factors and preterm births. Third, although our psychosocial instruments have been used and validated in South India, they were developed in the West and therefore may not have been sensitive to culturally specific manifestations of the disorders we studied. In other words, PTSD might look different in India and not follow the Western diagnostic profile that the PCL was built upon. Fourth, no women in the study admitted to experiencing sexual violence. This could be the result of legal definitions of sexual abuse that do not recognize sexual abuse in the marital context [42] and/or Indian women not feeling comfortable disclosing information on the culturally taboo subject of sex [6]. Lastly, we cannot determine causal links between domestic violence and mental health symptoms because this data was obtained through the women’s retrospective account of domestic violence. Though difficult to conduct, prospective longitudinal studies of domestic violence would be necessary to solidify the causal link.

Our findings point to the importance of focusing on psychosocial and educational factors when addressing the United Nations Millennium Development Goal 4: Reducing Child Mortality. Both maternal education and psychosocial distress were strongly associated with preterm birth, the leading cause of under-five child mortality. As such, interventions that are built to reduce child mortality should include educational and psychological components that help empower women and reduce risk of preterm birth.

References

WHO (2012) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. World Health Organization, Geneva

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard M, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, Adler A, Garcia CV, Rohde S, Say L, Lawn JE (2012) National, regional and worldwide estimates of preterm birth. Lancet 379(9832):2162–2172

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2014) Global burden of disease profile: India. http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/country_profiles/GBD/ihme_gbd_country_report_india.pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2014

Zeitlin J, Szamotulska K, Drewniak N, Mohangoo AD, Chalmers J, Sakkeus L, Irgens L, Gatt M, Gissler M, Blondel B, Euro-Peristat Preterm Study Group (2013) Preterm birth time trends in Europe: a study of 19 countries. BJOG 120(11):1356–1365

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R (2008) Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 371:75–84

Kumar S, Jeyaseelan L, Suresh S, Ahuja RC (2005) Domestic violence and its mental health correlates in Indian women. Br J Psychiatry 187:62–67

Babu BV, Kar SK (2009) Domestic violence against women in eastern India: a population-based study on prevalence and related issues. BMC Public Health 9:129

Kimuna SR, Djamba YK, Ciciurkaite G, Cherukuri S (2013) Domestic violence in India: insights from the 2005–2006 national family health survey. J Interpers Violence 28(4):773–807

Rees S, Silove D, Chey T, Ivancic L, Steel Z, Creamer M et al (2011) Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial function. JAMA 306(5):513–521

Kabir ZN, Nasreen HE, Edhborg M (2014) Intimate partner violence and its association with maternal depressive symptoms 6–8 months after childbirth in rural Bangladesh. Glob Health Action 12(7):24725

Kanwal Aslam S, Zaheer S, Shafique K (2015) Is spousal violence being “Vertically Transmitted” through victims? Findings from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–2013. PLoS One 10(6):e0129790

Yee A (2013) Reforms urged to tackle violence against women in India. Lancet 381(9876):1445–1446

Oram S, Stockl H, Busza J, Howard LM, Zimmerman C (2012) Prevalence and risk of violence and the physical, mental, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: systematic review. PLoS Med 9(5):e1001224

Sanghavi P, Bhalla K, Das V (2009) Fire-related deaths in India in 2001: a retrospective analysis of data. Lancet 373:1282–1288

Varma D, Chandra P, Thomas T, Carey M (2007) Intimate partner violence and sexual coercion among pregnant women in India: relationship with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord 102:227–235

Martin SL, Mackie L, Kupper LL, Buescher PA, Moracco KE (2001) Physical abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. JAMA 285(12):1581–1584

Mahapatro M, Gupta RN, Gupta V, Kundu AS (2011) Domestic violence during pregnancy in India. J Interpers Violence 26(15):2973–2990

Stephenson R, Winter A, Hindin M (2013) Frequency of intimate partner violence and rural women’s mental health in four Indian states. Violence Again Women 19(9):1133–1150

Patel V, Kirkwood BR, Pednekar S, Pereira B, Barros P, Fernandes J et al (2006) Gender disadvantage and reproductive health risk factors for common mental disorders in women: a community survey in India. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63(4):404–413

Patel V, Prince M (2006) Maternal psychological morbidity and low birth weight in India. Br J Psychiatry 188:284–285

Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ (2010) A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(10):1012–1024

Sarkar NN (2013) The cause and consequence of domestic violence on pregnant women in India. J Obstet Gynaecol 33(3):250–253

Sarkar N (2008) The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol 28(2):266–271

Fung J, Gelaye B, Zhong QY, Rondon MB, Sanchez SE, Barrios YV, Hevner K, Qiu C, Williams MA (2015) Association of decreased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) concentrations in early pregnancy with antepartum depression. BMC Psychiatry 10(15):43

Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB (1999) Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 282(18):1737–1744

Poongothai S, Pradeepa R, Ganesan A, Mohan V (2009) Prevalence of depression in a large urban South Indian population: the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-70). PLoS ONE 4(9):e7185

Poongothai S, Pradeepa R, Ganesan A, Mohan V (2009) Reliability and validity of a modified PHQ-9 item inventory (PHQ-12) as a screening instrument for assessing depression in Asian Indians (CURES-65). J Assoc Phys India 57:147–152

Mohanraj R (2014) Psychometric data on Tamil language PHQ-9. Unpublished Data

Kessler R, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin K, Green J, Russo L et al (2011) Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011(68):1

Walker E, Newman E, Dobie D, Ciechanowski P (2002) Katon W (2002) Validation of the PTSD checklist in an HMO sample of women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 24:375–380

Yeager D, Magruder K, Knapp R, Nicholas J, Frueh B (2007) Performance characteristics of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist and SPAN in Veterans affairs primary care settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 29(4):294–301

Chandra P, Satyanarayana V, Carey M (2009) Women reporting intimate partner violence in India: associations with PTSD and depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health 12:203–209

Gakidou E, Cowling K, Lozano R, Murray CJ (2010) Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: a systematic analysis. Lancet 376(9745):959–974

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52(12):1048–1060

WHO (2012) Born too soon: the global action report on preterm birth. World Health Organization, Geneva

Bassani DG, Kumar R, Awasthi S, Morris SK, Paul VK, Shet A et al (2010) Causes of neonatal and child mortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. Lancet 376(9755):1853–1860

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes; Behrman RE, Butler AS (eds) (2007) Preterm birth: causes, consequences, and prevention. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Patacchioli FR, Perrone G, Merlino L, Simeoni S, Bevilacqua E, Capri O, Galoppi P, Brunelli R (2013) Dysregulation of diurnal salivary cortisol production is associated with spontaneous preterm delivery: a pilot study. Gynecol Obstet Invest 76(1):69–73

Basu A, Levendosky A, Lonstein J (2013) Trauma sequelae and cortisol levels in women exposed to intimate partner violence. Psychodyn Psychiatry 41(2):247–275

Grieger JA, Grzeskowiak LE, Clifton VL (2014) Preconception dietary patterns in human pregnancies are associated with preterm delivery. J Nutr 144(7):1075–1080. doi:10.3945/jn.114.190686 Epub 2014 Apr 30

Matthew P (2003) The law on rape. Indian Social Institute, New Delhi

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a seed grant from the University of Washington’s Center for the Global Health of Women, Adolescents, and Children (Global WACh). We would like to give special thanks to the participants of this study and our research assistants, Priya Kundem and Hema Latha.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, D., Kumar, S., Mohanraj, R. et al. The impact of domestic violence and depressive symptoms on preterm birth in South India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 225–232 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1167-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1167-2