Abstract

Genetic essentialism suggests that beliefs in genetic causes of mental illness will inflate a desire for social distance from affected individuals, regardless of specific disorder. However, genetic contingency theory predicts that genetic attributions will lead to an increased desire for social distance only from persons with disorders who are perceived as dangerous.

Purpose

To assess the interactive effect of diagnosis and attribution on social distance and actual helping decisions across disorders.

Methods

Undergraduate students (n = 149) were randomly assigned to read one of the six vignettes depicting a person affected by one of the three disorders (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression) with either a genetic or environmental causal attribution for disorder. Participants completed measures of perceived dangerousness, social distance, empathic concern, familiarity with mental illness, and actual helping decisions.

Results

When provided with genetic attributions, participants’ desire for social distance was greater for targets with schizophrenia relative to targets with depression or bipolar disorder. This effect was mediated by perceived dangerousness. The indirect effect of diagnosis on helping decisions, through social distance, was significant within the genetic attribution condition.

Conclusion

Consistent with genetic contingency theory, genetic attributions for schizophrenia, but not affective disorders, lead to greater desire for social distance via greater perceived dangerousness. Further, results suggest that genetic attributions decrease the likelihood of helping people with schizophrenia, but have no effect on the likelihood of helping people with affective disorders. These effects are partially accounted for by desired social distance from people with schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Genetic causal explanations for mental illness have been cast in increasingly optimistic terms over the last two decades [1]. Importantly, some authors caution that an emphasis on genetic causal factors may result in essentialist thinking about the nature of mental illness—that genes provide important information about the inherent nature of a person [2, 3]. These genetic essentialist perspectives suggest that genetic attributions, which imply a high level of uncontrollability, may result in reified beliefs about the undesirable features of acute mental illness (e.g., unpredictability and dangerousness) as being latent, stable, and intractable [2, 4]. Indeed, some evidence has shown that genetic causal explanations are associated with increased perceptions of mental illness as serious [5, 6] and persons with mental illness as dangerous relative to non-genetic attributions [7, 9]. Research also shows that genetic attributions, compared to non-genetic attributions, are associated with greater desire for social distance from persons with mental illness [9, 10].

In contrast, genetic contingency theory posits that the effect of genetic causal attributions on mental illness stigma varies as a function of the specific mental disorder in question [11]. For example, genetic causal explanations, by implying high latency and uncontrollability, should intensify perceptions of dangerousness and unpredictability only for disorders generally perceived to be associated with violent or unpredictable behavior (e.g., schizophrenia). In turn, high perceived dangerousness should lead to an increased desire for social distance only from individuals with disorders perceived as dangerous. Conversely, genetic attributions should have no effect on psychological conditions such as affective disorders (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder), which are generally judged as non-threatening.

Based on this theory, correlational findings from a large United States survey showed that genetic attributions for schizophrenia predicted increased perceptions of dangerousness and a trend toward greater desire for social distance [11]. However, endorsing genetic attributions for depression predicted lower perceptions of dangerousness and less desire for social distance. One experimental vignette study conducted with a sample of New Zealanders examined the disorder-specific effect of genetic attributions on social distance toward targets with schizophrenia, depression, and skin cancer [12]. In contrast to the previously reported findings, this study found that, relative to a non-genetic attribution, a genetic attribution produced significantly greater desired social distance from an individual depicted as having major depression and significantly reduced desired social distance from an individual depicted as having schizophrenia. These contradictory findings suggest a need for further experimental research to systematically examine mechanisms which may account for the disorder-specific effects of genetic causal attributions on stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors toward people with mental illness.

Extant literature in the area of mental illness stigma is largely restricted to the study of depression and schizophrenia [13, 14]. Additional research is needed to examine effects of genetic casual attributions for other disorders on stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors. Evidence has suggested that, like depression and schizophrenia, stigma is a substantial barrier to recovery for individuals with other mental health diagnoses such as bipolar disorder [15–17]. New research could also improve upon current measurement of stigmatizing attitudes. For example, studies in the field of mental illness stigma have relied primarily on social distance scales that measure self-reported behavioral intentions across a number of hypothetical interpersonal situations [18]. A criticism of these scales is that they do not directly assess actual social decisions [11, 19], and therefore, must be understood as mere proxies for real decision-making behavior [5, 12, 20–22]. Little work has been done to examine actual behaviors toward people with mental illness. For example, at least one experimental study has found that, relative to non-biological attributions, biomedical attributions are associated with greater intensity and frequency of electric shock administered toward people depicted as having mental illness during a learning task [23]. Additional studies are needed to assess the effects of causal attributions on other behaviors and decisions. Given the pervasive nature of stigmatizing attitudes and exclusionary behavior, helping decisions may represent an important and measureable social behavior toward people with mental illness. More work is needed not only to assess the relationship between social distance and actual social decisions (i.e., helping), but also to examine how causal attributions, diagnosis, and other established predictors of helping affect decisions to help people with mental illness.

The present research

The primary objective of this study was to examine how experimentally manipulated information about diagnoses (i.e., depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia) and causal attributions (i.e., genetic versus environmental) affect ratings of social distance and real helping decisions. The secondary objective was to examine the mechanisms underlying these putative relationships. First, we hypothesized that participants would desire greater social distance from a person with schizophrenia, relative to a person depicted as suffering from an affective disorder (i.e., bipolar disorder and major depression). Because of apparent similarities in affective features shared by bipolar disorder and major depression, we expected no differences in desired social distance for targets from these groups. Second, we expected to find an interaction of disorder by attribution on social distance, predicting that when provided with genetic attributions, participants’ desire for social distance would be greater toward a person with schizophrenia relative to a person with major depression or bipolar disorder. When provided environmental attributions, we expected no such differences. We also hypothesized that, in the genetic attribution condition, perceptions of dangerousness would mediate the effects of diagnosis-based differences on social distance. Finally, we hypothesized that social distance would be negatively associated with helping decisions and that, when given a genetic attribution, diagnosis would indirectly affect helping decisions via social distance.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from undergraduate psychology courses at a public university in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States. The following two eligibility criteria were used. First, participants were asked, “Have you ever been diagnosed with a mental illness?” Participants who responded “Yes” were not invited to participate. This was done to ensure that all participants provided public rather than self-stigmatizing perspectives regarding attitudes and behaviors toward people with mental illness. Second, participants were not invited to participate if they reported having taken an abnormal psychology class, because these individuals may have learned about the effects of causal attributions on social distance from persons with mental illness. All participants who initiated the study received course credit for their participation.

Procedure

Methods were approved by the appropriate institutional review board. All stimuli and measures were administered anonymously online to minimize socially desirable response biases [24, 25]. After obtaining consent, participants completed the two screening items described above, which assessed eligibility for the study. Next, participants read a description of symptoms associated with depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia and rated their beliefs about the cause of each disorder on separate scales from 1 (completely environmental) to 7 (completely genetic). This measure allowed for unbiased collection of pre-manipulation, causal attributions for mental illness.

Eligible participants were contacted by email approximately 2 weeks after the screening and were given a link to an online survey. After giving informed consent, participants completed measures of sociodemographics and familiarity with mental illness, and were randomly assigned to read one of the six vignettes depicting an individual with major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia, which were described as being caused by either genetic or environmental factors. Next, participants rated the extent to which they believed that the disorder was due to environmental versus genetic risk factors. Participants then completed measures of social distance, perception of dangerousness, and empathic concern toward the described individual.

Next, participants were notified that they had completed the data collection portion of the study and were told that the study researchers had been contacted by a mental health advocacy group to request assistance in recruiting student volunteers. Participants were then offered an (ostensible) opportunity to volunteer to work with people with serious mental illness, and told that, should they agree to volunteer, they would be contacted (via email) by a local community member with serious mental illness within the next week to schedule a brief volunteer opportunity for the coming semester. Participants responded “yes” or “no” to indicate their decision.

Following this, a funnel debriefing process was used to assess participants’ awareness of the causal attribution manipulation and fictional nature of the volunteer opportunity. That is, broad, open-ended questions were first asked, followed by increasingly specific questions, which assessed beliefs concerning (a) the purpose of the study, (b) the experimental manipulation, and (c) the deceptions regarding the volunteer experience. For example, participants were first asked: “In your opinion, what were the researchers trying to study in this experiment?” Any response that mentioned the intentions of the researchers to manipulate causal attributions and measure response or any response that mentioned suspicion regarding the fictitious volunteer opportunity was determined to reflect participant awareness of the manipulations. Finally, participants were debriefed about the interactive nature of genetic and environmental causes of mental disorders and were informed about the nature and purpose of the deception used in the study.

Experimental manipulations

Diagnosis

Vignettes depicted a man named Jamie described as experiencing either symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, or bipolar disorder, based on DSM-IV-TR criteria for each disorder. See the Appendix. The vignettes used for the depression and schizophrenia conditions were based on work from Breheny [12].

Attribution

Genetic and environmental causal attributions were experimentally manipulated at the end of each vignette. For example, for the genetic attribution within the schizophrenia condition participants were told: “At the hospital Jamie underwent comprehensive psychological and medical testing, which included genetic testing. The results of these tests indicated that Jamie had a disorder called schizophrenia. Unlike other mental illnesses, which are due to environmental factors, such as difficult or stressful situations, current research has found that schizophrenia is caused by genetic factors, such as defective or improperly functioning genes.” Conversely, participants in the environmental attribution were given the same information but told that, “Unlike other mental illnesses, which are due to genetic factors such as defective or improperly functioning genes, current research has found that schizophrenia is caused by environmental factors such as difficult or stressful situations.”

Manipulation checks

A single item assessed agreement with the causal attribution provided in the vignette (“Please rate the extent to which you believe that Jamie’s illness is due to either environmental or genetic factors.”). Ratings were on a scale ranging from 1 (completely environmental) to 7 (completely genetic).

Primary dependent variables

Social distance

The Social Distance Scale is a 10-item measure of willingness to engage in hypothetical activities with a target person at increasing levels of intimacy [12]. This scale uses items taken from two pre-existing social distance scales [5, 20] and has demonstrated excellent internal consistency in these studies (α = 0.94). In the current study, reliability was also excellent (α = 0.93). For each item, participants were asked to rate their willingness to interact with the person depicted in the vignette. Ratings were made on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely unwilling) to (5 definitely willing). All items were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated greater social distance, and averaged to create the total score.

Helping

Helping decisions were assessed by participants’ “yes” or “no” responses regarding whether they wished to participate in a volunteer opportunity with (respectively, depending on condition) a person diagnosed with major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia.

Mediator and covariates

Perception of dangerousness

A single question assessed participants’ perception of the target of each vignette as dangerous: “Please rate to what extent you believe that Jamie is dangerous.” Responses were on a 7-point scale from 1 (not at all dangerous) to 7 (extremely dangerous).

Familiarity with mental illness

The Level-of-Contact Report consists of 12 hierarchically ordered relationships ranging from lesser contact (e.g., I have observed, in passing, a person I believe may have had a severe mental illness) to greater contact (e.g., A friend of the family has a severe mental illness) with persons with mental illness [26]. Items were hierarchically ordered in terms of level of contact by three expert raters with good inter-rater reliability (α = 0.83) [26]. Participants were asked to endorse all relationships that apply. Higher rankings indicated a more intimate level of contact, and the highest ranked item endorsed on the measure is the participant’s level of contact score. The Level-of-Contact report has been shown to predict hypothetical helping toward persons with mental illness [26].

Empathic concern

Empathic concern was assessed using participants’ rating of six emotions (sympathetic, soft-hearted, warm, compassionate, tender and moved) felt toward the individual depicted in the vignette on a 7-point scale (e.g., 1 = not at all sympathetic to 7 = extremely sympathetic). These adjectives have been used in previous research to assess empathic concern, have excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90), and aggregate responses have been consistently shown to predict helping behavior [27]. The internal consistency of these items within the current sample was good (α = 0.84). Items were summed, and higher scores indicate greater empathic concern for the target.

Statistical analyses

The effectiveness of the experimental manipulation on causal beliefs was assessed using a 2 (attribution condition: environmental vs. genetic) × 2 (pre vs. post-manipulation) mixed ANOVA with repeated measures on the second factor. Next, two planned contrasts were used to examine the simple effects of time (pre vs. post-manipulation) on causal beliefs at the level of each attribution (i.e., genetic and environmental).

A 2 (attribution: environmental vs. genetic) × 3 (diagnosis: depression, bipolar, or schizophrenia) ANOVA was used to examine the effects of attribution and diagnosis on social distance. Next, two planned contrasts pitted the schizophrenia diagnosis group against the combined bipolar and depressed groups (contrast 1), and the bipolar group against the depressed group (contrast 2). All subsequent analyses involving diagnosis compared schizophrenia versus the weighted combination of both affective disorders. Two simple contrasts were also used to test the effects of disorder (schizophrenia versus the combined affective disorders) on social distance at each level of attribution (i.e., genetic and environmental). Finally, a path model with bootstrapping (5,000 replications) was used to estimate the standard error of the indirect effect of diagnosis (i.e., comparing the target with schizophrenia against the targets with affective disorders) on social distance via perceptions of dangerousness. A separate path model was used to examine the indirect effect of diagnosis (using the simple contrast specified above) on helping decisions via social distance. This model was then retested while statistically controlling for potential covariates of helping (i.e., empathic concern and familiarity with mental illness). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19 [28]. Path models were tested using a SPSS macro provided by Preacher and Hayes [29]. All tests were two-tailed and alpha was set at 0.05.

Results

Sample

A total of 397 individuals were initially screened into the study using the two exclusion criteria. Fifty-one participants responded “Yes” to the question regarding prior diagnosis with mental illness and were not invited to participate in the study. In addition, 154 individuals reported prior enrollment in an abnormal psychology class. Four participants were dropped from the analysis because of suspicion regarding the causal attribution manipulation. Four additional participants were excluded after indicating some suspicion about the nature of the (fictional) volunteer experience. The final sample consisted of 149 participants who were predominately non-Hispanic (n = 137, 91.9 %), white (n = 132, 88.6 %), and female (n = 100, 67.1 %). The age of the sample ranged from 18 to 36 (M = 20.36, SD = 2.82).

Manipulation check

As expected, a significant main effect of time (i.e., differences in causal beliefs pre- to post-manipulation, collapsed across attribution) was found, indicating that the manipulation was successful in altering participants’ rating of causal beliefs regarding mental illness F(1, 147) = 9.18, p = 0.003. The expected time-by-attribution interaction also emerged, F(1, 147) = 70.04, p < 0.001. In the genetic condition, there was greater endorsement of a genetic cause following the manipulation (M = 5.04, SD = 1.12) than prior to the manipulation. (M = 4.38, SD = 1.31), t(148) = 4.61, p < 0.001, d = 0.54. In the environmental condition, endorsement of an environmental cause was greater following the manipulation (M = 3.21, SD = 1.31) than prior to it (M = 4.63, SD = 1.11), t(148) = −9.83, p < 0.001, d = 1.17.

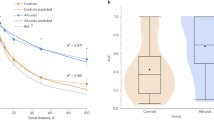

Predictors of social distance

Results showed a significant main effect of diagnosis on social distance, F(2, 143) = 3.41, p = 0.006 (Table 1). As expected, collapsed across attribution conditions, social distance scores were significantly greater in the schizophrenia condition relative to the combined bipolar disorder and depression conditions, t(143) = −3.18, p = 0.002, d = 1.20. Also as predicted, the second contrast was not significant, d = 0.05, showing that the depressed and bipolar conditions did not differ on degree of desired social distance. No main effect of attribution condition on social distance emerged. However, the hypothesized interaction of attribution by diagnosis on social distance was confirmed (Fig. 1), F(2, 143) = 3.41, p = 0.036. As predicted, when given genetic attributions, the schizophrenia condition significantly differed from the combined affective disorders on social distance, t(143) = 4.02, p < 0.001, d = 1.42. However, at the level of environmental attributions, the effect of diagnosis was not significant, d = 0.10. This suggests that genetic attributions lead to greater social distance from a target with schizophrenia relative to targets with depression and bipolar disorder (which do not differ), but that environmental attributions do not produce any such differences.

The role of perceived dangerousness

A path model showed that, within the genetic attribution condition, the affective conditions had lower ratings of dangerousness relative to the schizophrenia condition, B = −0.25, SE = 0.10, t = −2.55, p = 0.011, and that greater perceptions of dangerousness were associated with greater social distance, B = 0.32, SE = 0.07, t = 6.41, p < 0.001 (Fig. 2). The indirect effect of diagnosis on social distance through perceptions of dangerousness was significant, B = −0.08, 99 % CI = [−0.17, −0.01], p < 0.01.

The indirect effect of diagnosis [schizophrenia (SZ) vs. major depression (MD) and bipolar disorder (BP)] on social distance, mediated by perceptions of dangerousness, at the level of genetic attribution. Note: B is an unstandardized regression coefficient. The indirect effect of the diagnosis contrast on social distance was significant B = −0.08, 99 % CI = [−0.19, −0.01], p < 0.01. The direct effect of diagnosis on social distance was significant, p = 0.002. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001

The relationship of social distance to helping decisions

Results from a second path model showed that relative to affective disorders, schizophrenia was associated with greater social distance, B = −0.27, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, and greater social distance was associated with a lower probability of helping, B = −0.94, EXP(B) = 0.39, p < 0.001. The indirect effect of diagnosis on helping decisions through social distance was significant, B = 0.26, 99 % CI = [0.07, 0.58], EXP(B) = 1.29, p < 0.01. This suggests that, for genetic attributions, decisions to help are half as likely for a person with schizophrenia relative to a person with an affective disorder, mediated by greater desire for social distance (Fig. 3). Finally, we tested the same path model while controlling for two established covariates of helping (i.e., empathic concern and familiarity with mental illness). Of the covariates, only empathic concern was significantly associated with helping, r = 0.24, p = 0.004. However, the indirect effect of diagnosis on helping remained significant when controlling for these covariates, p < 0.01.

The indirect effect of diagnosis [schizophrenia (SZ) vs. major depression (MD) and bipolar disorder (BP)] on likelihood of offering to help, mediated by social distance, at the level of genetic attribution. Note: B is an unstandardized regression coefficient, EXP(B) are odds ratios. The indirect effect of the diagnosis contrast on the likelihood of helping was significant, B = 0.26, 99 % CI = [0.07, 0.60], EXP(B) = 1.29, p < 0.01. The direct effect of diagnosis contrast on helping was not significant, p = 0.98. *p < 0.001

Discussion

Social distance

Results from this experimental study were consistent with predictions made by genetic contingency theory. Participants provided with a genetic causal explanation for schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder desired greater social distance from a target with schizophrenia compared to targets with affective disorders. However, when provided with environmental causal explanations, this difference among diagnoses was not evident. This finding builds on previous correlational findings [11] by providing causal evidence for the disorder-specific effect of genetic attributions on social distance.

Importantly, and consistent with genetic contingency theory, we found that the increased desire for social distance from persons with schizophrenia was mediated by increased perceptions of dangerousness. This result is consistent with correlational findings from a large vignette study conducted with a German sample showing that perceived dangerousness mediated the relationship between endorsement of biogenetic causal explanations for schizophrenia and social acceptance [30]. However, results from the current study are some of the first to provide experimental evidence showing that, compared to environmental attributions, genetic attributions lead to greater perceptions of dangerousness, which are in turn associated with greater desire for social distance from a person with schizophrenia.

In addition to providing support for genetic contingency theory, results from the current study provide evidence that is inconsistent with notions of genetic essentialism. According to genetic essentialist perspectives, genetic attributions for mental illness should lead to a similarly high desire for social distance across all types of mental health diagnoses. However, within the current study, no main effect of causal attribution (i.e., genetic versus environmental) on social distance was found. This result suggests that genetic attributions may not have broad negative consequences for social distance across all disorders.

An additional contribution of the current study was the examination of a relatively understudied diagnosis within the stigma literature (i.e., bipolar disorder). Specifically, we found no significant differences in ratings of social distance between bipolar and depressed targets. Few studies have assessed social distance from persons with bipolar disorder [31, 32], and to our knowledge, the present study is one of the first to directly compare ratings of social distance for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. Our findings suggest that desire for social distance from people with bipolar disorder and depression is reasonably similar, perhaps because of salient affective features common to both disorders. Moreover, the similar effect of genetic attributions on social distance for these affective disorders (i.e., disorders not typically associated with dangerousness) lends even greater support to genetic contingency theory.

Helping

The secondary goal of this study was to assess whether there was any relationship between an explicit measure of social distance and peoples’ actual willingness to help persons with mental illness. To our knowledge, few if any published reports have examined links between actual decisions and hypothetical behavioral intentions [33, 34]. This omission is problematic because it has been suggested that self-report measures (such as social distance scales) may have little ecological validity [14], and thus, may not accurately reflect actual behaviors toward persons with mental illness [5, 12, 20–22]. However, the present finding showing a significant negative association between desire for social distance and probability of deciding to help lends support to the possibility that social distance scales are an effective proxy for at least one type of actual behavior—helping decisions.

Of interest, we also found that, for participants given genetic attributions, social distance mediated actual likelihood of helping decisions, even when controlling for other variables that in prior research have been associated with helping decisions (which were also associated with helping in the current sample). For example, empathy has been shown to predict helping toward stigmatized groups, and familiarity with mental illness is positively associated with greater hypothetical helping behavior toward persons with mental illness [35, 36]. Current findings showed that diagnosis accounted for significant variability in helping decisions as a function of social distance—above and beyond effects of familiarity or empathic concern.

Limitations

The current findings are qualified by five potential limitations. First, the causal explanations provided in the current study (i.e., completely genetic or completely environmental) are not entirely consistent with current perspectives on the causes of mental disorders, which are better represented by gene/environment interactions. In this way, some generalizability was sacrificed to more precisely examine the effect of specific attributions on social distance. These findings underscore the negative consequences of increasingly prevalent reductionist genetic causal explanations for schizophrenia [11]. A second potential limitation of the study is that, while the assessment of helping involved real prospective helping decisions, it did not measure actual helping. However, measuring actual decisions to help represents an improvement over measures of purely hypothetical behavioral intentions. Future research should include more direct measures of behavior, as well as new (i.e., non-helping) paradigms to assess real stigmatizing and discriminatory behavior directed toward people with mental illness. For example, electric shock paradigms [23] or physical proximity [37] could be used as a measure of real punitive behaviors and actual social distancing practices. Third, attitudes of the undergraduate sample used in this study may not reflect those of the general population [20]. Fourth, perceptions of dangerousness were assessed using a single item, which may limit the validity of this measure. Fifth, the vignettes used for the current study depicted a male target. The effects of causal attributions on stigmatizing attitudes may vary as a function of disorder and gender. This consideration may be especially important for disorders that are perceived as dangerous or threatening. New research should assess the combined effects of gender, diagnosis, and causal attributions on desired social distance and helping behavior.

Conclusions

As genetic explanations for mental illness increase, public perceptions of persons with schizophrenia as dangerous may also increase. Increased perceptions of dangerousness may in turn escalate desire for social distance while decreasing decisions to help people with schizophrenia. These findings, and others that question the assumption of a genetic etiology for schizophrenia [38], suggest that the dissemination of information regarding genetic causes of schizophrenia should be minimized or at least tempered with information regarding the relatively low base rates of interpersonal violence among persons with schizophrenia.

Persons with mental illness often face difficulties at an interpersonal level, which may limit access to basic needs such as housing [39] and employment [40]. Therefore, interpersonal willingness to help represents a potentially important social behavior. Findings from the current study suggest that interventions targeted to promote helping toward persons with mental illness should focus on reducing desired social distance, perhaps by decreasing perceptions of dangerousness.

References

Conrad P (2001) Genetic optimism: framing genes and mental illness in the news. Cult Med Psychiatry 25(2):225–247

Dar-Nimrod I, Heine SJ (2011) Genetic essentialism: on the deceptive determinism of DNA. Psychol Bull 137(5):800–818. doi:10.1037/a0021860

Nelkin D, Lindee MS (1995) The DNA mystique: the gene as cultural icon. WH Freeman and Company, New York

Haslam N (2011) Genetic essentialism, neuroessentialism, and stigma: commentary on Dar-Nimrod and Heine (2011). Psychol Bull 137(5):819–824. doi:10.1037/a0022386

Phelan JC (2005) Geneticization of deviant behavior and consequences for stigma: the case of mental illness. J Health Soc Behav 46(4):307–322

Phelan JC (2002) Genetic bases of mental illness—a cure for stigma? Trends Neurosci 25(8):430–431

Jorm AF, Griffiths KM (2008) The public’s stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: how important are biomedical conceptualizations? Acta Psychiatr Scand 118(4):315–321. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01251.x

Read J, Harré N (2001) The role of biological and genetic causal beliefs in the stigmatisation of ‘mental patients’. J Ment Health 10(2):223–235. doi:10.1080/09638230123129

Rusch N, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Corrigan PW (2010) Biogenetic models of psychopathology, implicit guilt, and mental illness stigma. Psychiatry Res 179(3):328–332. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.010

Dietrich S, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2006) The relationship between biogenetic causal explanations and social distance toward people with mental disorders: results from a population survey in Germany. Int J Soc Psychiatry 52(2):166–174

Schnittker J (2008) An uncertain revolution: why the rise of a genetic model of mental illness has not increased tolerance. Soc Sci Med 67(9):1370–1381. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.07.007

Breheny M (2007) Genetic attribution for schizophrenia, depression, and skin cancer: impact on social distance. N Z J Psychol 36(3):154–160

Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S (2006) Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: a review of population studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 113(3):163–179. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00699.x

Boysen GA, Gabreski JD (2012) The effect of combined etiological information on attitudes about mental disorders associated with violent and nonviolent behaviors. J Soc Clin Psychol 31(8):852–877. doi:10.1521/jscp.2012.31.8.852

Elgie R, Morselli PL (2007) Social functioning in bipolar patients: the perception and perspective of patients, relatives and advocacy organizations—a review. Bipolar Disord 9(1–2):144–157. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00339.x

Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, Sirey JA, Salahi J, Struening EL, Link BG (2001) Stigma as a barrier to recovery: adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr Serv 52(12):1627–1632

Vazquez GH, Kapczinski F, Magalhaes PV, Cordoba R, Lopez Jaramillo C, Rosa AR, Sanchez de Carmona M, Tohen M (2011) Stigma and functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 130(1–2):323–327. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.012

Hinshaw SP, Stier A (2008) Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 4:367–393. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245

Stier A, Hinshaw SP (2007) Explicit and implicit stigma against individuals with mental illness. Austral Psychol 42(2):106–117. doi:10.1080/00050060701280599

Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, Rossler W (2004) Factors influencing social distance toward people with mental illness. Commun Ment Health J 40(3):265–274

Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY (2004) Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull 30(3):511–541

Corrigan PW (2000) Mental health stigma as social attribution: implications for research methods and attitude change. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 7(1):48–67. doi:10.1093/clipsy/7.1.48

Mehta S, Farina A (1997) Is being ‘sick’ really better? Effect of the disease view of mental disorder on stigma. J Soc Clin Psychol 16(4):405–419. doi:10.1521/jscp.1997.16.4.405

Joinson A (1999) Social desirability, anonymity, and Internet-based questionnaires. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 31(3):433–438

Link BG, Cullen FT (1983) Reconsidering the social rejection of ex-mental patients: levels of attitudinal response. Am J Commun Psychol 11(3):261–273

Holmes EP, Corrigan PW, Williams P, Canar J, Kubiak MA (1999) Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 25(3):447–456

Batson CD, Eklund JH, Chermok VL, Hoyt JL, Ortiz BG (2007) An additional antecedent of empathic concern: valuing the welfare of the person in need. J Pers Soc Psychol 93(1):65–74. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.65

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (2010), 19th edn. IBM Corp, Armonk

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891

Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2013) Causal beliefs of the public and social acceptance of persons with mental illness: a comparative analysis of schizophrenia, depression and alcohol dependence. Psychol Med, 1–12. doi:10.1017/S003329171300072X

Feldman DB, Crandall CS (2007) Dimensions of mental illness stigma: what about mental illness causes social rejection? J Soc Clin Psychol 26(2):137–154. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.2.137

Sears PM, Pomerantz AM, Segrist DJ, Rose P (2011) Beliefs about the biological (vs. nonbiological) origins of mental illness and the stigmatization of people with mental illness. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 14(2):109–119. doi:10.1080/15487768.2011.569665

Jorm AF, Oh E (2009) Desire for social distance from people with mental disorders. Austral N Z J Psychiatry 43(3):183–200. doi:10.1080/00048670802653349

Read J, Haslam N, Sayce L, Davies E (2006) Prejudice and schizophrenia: a review of the ‘mental illness is an illness like any other’ approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand 114(5):303–318. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00824.x

Batson CD, Chang J, Orr R, Rowland J (2002) Empathy, attitudes and action: can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 28(12):1656–1666. doi:10.1177/014616702237647

Corrigan P, Markowitz FE, Watson A, Rowan D, Kubiak MA (2003) An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav 44(2):162–179. doi:10.2307/1519806

Bessenoff GR, Sherman JW (2000) Automatic and controlled components of prejudice toward fat people: evaluation versus stereotype activation. Soc Cogn 18(4):329–353. doi:10.1521/soco.2000.18.4.329

Joseph J (1999) The genetic theory of schizophrenia: a critical overview. Ethical Hum Sci Serv 1(2):119–145

Page S (1995) Effects of the mental illness label in 1993: acceptance and rejection in the community. J Health Soc Policy 7(2):61–68

Stuart H (2006) Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatry 19(5):522–526. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000238482.27270.5d

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (P20RR016474) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103432) from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Vignettes

Appendix: Vignettes

Schizophrenia

Imagine a person named Jamie. Usually Jamie gets along well with his family and coworkers. He enjoys reading and going out with friends. About a year ago Jamie started thinking that people were spying on him and trying to hurt him. Jamie became convinced that people could hear what he was thinking. He also heard voices when no one else was around. Sometimes he even thought people on TV were sending messages especially to him. Jamie began to isolate himself because he believed that many people were out to get him. Jaime’s friends and family became extremely worried about his increasingly odd behavior. After living this way for about 6 months, Jamie was admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Major depression

Imagine a person named Jamie. Usually Jamie gets along well with his family and coworkers. He enjoys reading and going out with friends. About a year ago Jamie started feeling very down and unhappy. Jamie found it very hard to get out of bed, get dressed, and go to work, or do anything. Jamie just did not get any pleasure out of anything the way he normally would. He often did not feel like eating and he had trouble sleeping. Jamie also felt completely worthless and even had thoughts about killing himself. After having these problems off and on for about 6 months, Jamie was admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Bipolar disorder

Imagine a person named Jamie. Usually Jamie gets along well with his family and coworkers. He enjoys reading and going out with friends. About a year ago Jamie started to experience significant changes in his mood. He experienced periods where his mood became very elevated. During these periods, Jamie slept very little and spent many hours on school work and other projects. Additionally, during these periods, Jamie’s friends said he became so talkative and hyper that he was difficult to understand. At other times Jamie would feel so down that he lost interest in everything and avoided friends and family. During these periods, Jamie had thoughts about killing himself. After having these mood swings for about 6 months, Jamie was admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, A.A., Laurent, S.M., Wykes, T.L. et al. Genetic attributions and mental illness diagnosis: effects on perceptions of danger, social distance, and real helping decisions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49, 781–789 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0764-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0764-1