Abstract

Objective

To explore the quantitative and qualitative aspects of friendship in people with schizophrenia. To examine emotional and behavioural commitment, experiences of stigma, and the impact of illness factors that may affect the making and keeping of friends. The difference in the perception between the researcher and participants of the presence of problems in friendships was also investigated.

Methods

The size and quality of the social networks of 137 people with established schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, aged 18–65 in one geographical area of southeast England was ascertained using a semi-structured interview. Qualitative aspects of friendship were measured using objective, pre-determined, investigator-rated criteria.

Results

The mean number of friends reported by respondents was 1.57. Men were less likely to report friendships than women (29 vs. 53%, χ 2 = 13.51, df 1, p < 0.001). Of the 79 people who had a friend, 75 named someone amongst fellow service users. The quality of these friendships was generally good. Emotional commitment to friendship and mistrust were more important than current clinical state in determining whether or not the participant has friends. Most of those without friends did not see the lack of friendship as a problem. The researcher was up to three times more likely to report a problem than the participant.

Conclusions

The friendship network size was found to be small but the quality of friendship mostly positive and highly valued. The majority of friendships were with other service users made during attendances at day hospitals and drop-in centres thus underscoring the importance of this service provision. Psychosocial intervention programmes need to take into account psychological factors that impact upon friendship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People with schizophrenia have been found to have fewer numbers of friends and narrower social networks compared to the general population [1]. Some of this may be explained by premorbid factors including low self-esteem, low social confidence and the communication skills that are necessary for the formation of relationships [2]. It may also reflect neurocognitive deficits which impact upon social, communication and interpersonal functioning. The severity and nature of symptoms, and duration of illness also influence relationship formation and interaction [3–5]. In addition, it may result from low motivation, apathy and social withdrawal, and this withdrawal may be seen as a way of avoiding arousal and overstimulation which can lead to a relapse [6–8]. The secondary effects of schizophrenia, including loss of social role and networks, unemployment, lack of stable housing, financial problems and stigma, also have a negative impact on relationship functioning and lead to social isolation [9, 10].

Friendships are voluntary relationships where individuals have to commit time and effort in order to develop mutual and personalised interest and concern [11]. Factors such as trust, intimacy, and commitment are therefore important in the development and maintenance of friendship. These psychological variables and their relevance have been studied extensively in the general population [12]. So far aside from the impact of symptoms and disability associated with schizophrenia there has been no research conducted on these psychological variables and friendship in people with schizophrenia. Yet an understanding of these processes might be very informative for rehabilitation interventions that aim to improve social skills and reduce social isolation and exclusion.

We undertook a survey of all people with schizophrenia in one geographical area [13]. Our primary interest was their sexual problems, but we also examined their social networks, support and friendships. This mixed-methods study allowed us to explore the quantitative and qualitative aspects of friendship in established schizophrenia, and in particular, the interplay of emotional and behavioural commitment to social relationships, mistrust, and fear of intimacy that may affect the making and keeping of friends. We also examined the impact of illness handicap and stigma on friendships and the difference in the perception between the researcher and participants of the presence of problems in friendships.

Method

Study site

The survey was conducted in St. Leonards-on-Sea, a seaside town on the south coast of England which has urban and suburban areas. The national government statistics showed the mid-2001 population for the age group 16–64 to be 28,306 (2001 census, http://www.Neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk). Only 3% of residents are nonwhite ethnic groups.

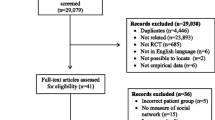

Sample

The sampling frame was all agencies in the local area, including general practices, who had contact with people known to have schizophrenia. The study sample consisted of all people aged 18–65 residing in the geographical area of St. Leonards-on-sea, East Sussex, who were known to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as defined by DSM-IV [14] with a duration of illness of at least 2 years. People who were homeless were excluded, partly due to the logistics of locating them and partly because their relationship status may be influenced by a different set of problems. People with a co-morbid clinical diagnosis of Learning Disability were also excluded. The process of recruitment is described in detail in a related paper [13].

Data collection

A face-to-face semi-structured interview was used in order to encourage participants to speak freely and to tell their story, whilst at the same time allowing the interviewer control over the topics dealt with and the range and breadth of the subject matter.

Definition of ‘friend’

We allowed the respondents to define who their friends were for the purposes of the study. However, we found that several respondents included family members and mental health professionals as their friends and some had ‘imaginary’ friends. In view of this we added some limits as to whom we included in the list of friends. A ‘friend’ was defined in this study as a person in the participant’s social network who is non-kin, not part of the professional support or service provider system, perceived by the respondent as a friend, with evidence of shared activities, interests and interaction and evidence of actual contact at least once over the past 3 months. People in intimate and sexual relationships with the participant were excluded as friends for the purpose of this study. Problems in these relationships are studied in a separate paper [13].

Measures

Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) [15]

The PANSS is a widely used measure of clinical functioning in patients suffering from schizophrenia. It addresses symptoms and observed behaviours over the preceding 7 days.

Global Assessment of Function (GAF) [16]

This is a modified version of the Global Assessment Scale developed by Endicott and colleagues that assesses psychological, social and occupational functioning. A single overall rating of global functioning was used in this study.

Social Behavioural Scale (SBS) [17]

This is a semi-structured interview assessment which covers 21 items of behaviour from personal appearance and hygiene to social mixing and communication. Information was provided by an informant who knew the participant best, typically a relative or a care coordinator. The total score, representing severity of behavioural disturbance, is reported in this paper.

Measuring friendship

We adopted a two-stage approach to the assessment of friendship taking first an overview of the respondent’s understanding of the term and the importance they placed on friendships in general and then collecting more detailed accounts of the numbers and characteristics of particular friendships. Two main ratings were used.

The Self Evaluation and Social Support Scale (SESS) [18]

This semi-structured instrument was used to gather an overall view of the importance of friendship in their lives, rating attitudes to friendship across a number of domains from both the respondent’s view and from that of the investigator who bases his/her ratings on the detailed comments substantiated by descriptions of behaviour that exemplify the general assertions of the respondent. Except where otherwise mentioned, our analyses are based on the investigator’s view.

Ratings for each sub-scale are made on a 4-point ordinal scale (4 little/none, 3 some, 2 moderate, 1 marked; for the present study 4 and 3 were re-coded as ‘low’ and 2 and 1 re-coded as ‘high’).

-

(a)

Commitment to friends Rated separately for the participants’ emotional and behavioural commitment. Emotional commitment reflects the importance of having friends, the extent to which this is valued and desired by the participant. Someone might value friendship but have no friends currently. Behavioural commitment assesses actions on the participants’ part to make and sustain friendships.

-

(b)

Mistrust of others The extent to which the participants consider themselves trusting of others, whether they are suspicious of others’ behaviour and motives, and the fear of being let down.

-

(c)

Fear of intimacy The extent to which the participants feel uncomfortable or anxious when others try to get close, whether past adverse experiences have increased fears that they will be rejected by others if they get too close. It also assesses the extent to which such fears or discomfort is generalised to all others or whether only certain categories of people are included.

-

(d)

Quality of social interaction Measures the intensity and pervasiveness of the participants’ feelings about the level of enjoyment in their interaction with friends, whether it is warm, pleasant, neutral, relaxed, tensed, or boring. It also looks at the relative frequency and duration of various episodes of activity.

Significant Others Scale (SOS) [19]

The SOS was used to gather details of reported friendships. It measures an individual’s perceived support, with useful distinctions of actual versus ideal and emotional versus practical support. Participants are asked for each named friend to rate the quality of friendship on a 7-point scale in terms of emotional and practical support actually received and what they would ideally desire.

Perceived stigma

Link and Phelan [20] constructed a definition that links different components of stigma, including the labelling, stereotyping, status loss, separation, and discrimination of people based on human differences. This measure reflects the emotional responses of the participant regarding how their mental illness affects their lives, and whether they are being treated differently by others, at work or socially. This perceived (felt) stigma is different from enacted stigma. Enacted stigma refers to actual discrimination, whereas perceived stigma refers to the fear of such discrimination, leading to concealment of the problem. In this sense perceived stigma can be more disruptive to a person’s life [21].

We used questions that explored the subject’s perceived level of stigma, based on the conceptualization of stigma by Link and Phelan [20].

Reliability

Following training in the measures, inter-rater reliability of the investigators was checked by blind rating of 14 transcripts. Agreement was good with weighted Kappas ranging from 0.85 (emotional commitment) to 0.94 (quality of positive social interaction).

Analysis

Results were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 10 for windows. Comparisons between variables were carried out using Chi-square or McNemar tests. Quotes from participants are given to clarify and illustrate the quantitative findings.

Results

A total of 151 people with a clinical DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder of at least 2 years’ duration were identified in the St. Leonards-on-Sea area. 137 (91%) agreed to take part in the study and were interviewed (81 men and 56 women). There were no significant differences in age, sex, ethnicity, social class, marital/relationship status or current living arrangements between those who were interviewed and those who were not.

A third of the sample lived alone. 124 (91%) of the sample were white English and 120 (88%) were working class (manual) and unemployed. Forty-one (30%) of participants were currently in a relationship (all heterosexual); 80 (58%) had never had an intimate relationship and 121 (88%) had never had children. Significantly more of the women were currently in an intimate relationship than were men (women: 24, 43% vs. men: 17, 21%, χ 2 = 7.551, df = 1, p = 0.006). More men (n = 55, 68%) than women (n = 15, 27%) had never had an intimate relationship (χ 2 = 22.399, df = 1, p = 0.000) and significantly more men than women never had children (men: 71, 88% vs. women: 37, 66%. χ 2 = 9.243, df = 1, p = 0.002).

The participants were fairly stable clinically with a mean PANSS positive symptom score of 14.5 (SD = 6.4) and a mean negative symptom score of 15.4 (SD = 8.4). The average GAF score was 54.2 (SD = 18.7) and the average total SBS score was 11.9 (SD = 9.8) together indicating moderate social impairment. The mean duration of the disorder was 20.43 years (SD 11.7). 92 (61%) had been in contact with mental health services for at least 15 years, 64 (42%) had been admitted at least once in the previous 18 months and 41 (27%) had co-morbid problems of substance abuse or dependency. All but five patients were currently prescribed antipsychotic medication.

Attitudes to friendship

Participants had very definite ideas about the difference between a friend and an acquaintance, as illustrated in the following quote:

I don’t have friends, I have acquaintances; high street acquaintances, shop acquaintances, café acquaintances. I bump into them when I go out. I smile at them, we talk, we have conversation. That’s about it. I do not plan to do anything with them. I go for my cups of tea and just talk to whoever that’s around. I wouldn’t want them to come to my home.

Male, age 49

Nearly half the sample (43%, 58/137) reported a high level of emotional commitment to friendship but this desire was only accompanied by regular attempts to make friends and overcome social obstacles by 22 participants. Not surprisingly, people without friends were more likely to report low emotional and behavioural commitment to friendship, greater fear of intimacy and greater mistrust of other people than those with friends. Emotional and behavioural commitment are moderately correlated (ρ = 0.51, p < 0.01), and are associated in a dose–response manner to the number of reported friendships so that of the 36 who reported no emotional commitment to friendship none had friends compared with 58% (25/43) of those with some commitment, and 100% (25/25) of those with marked commitment.

Men were less likely than women to describe high emotional commitment to friendship [35% (28/81) vs. 54% (30/56), χ 2 4.89, df = 1, p = 0.03] and more likely to describe a fear of intimacy in relationships [64% (52/81) vs. 46% (26/56), χ 2 = 4.26, df = 1, p = 0.04].

The following quotes illustrate the role of these attitudes in making friends:

I love to have friends. I think we all need people round us. I get very lonely sometimes and go from one day to the next without having any meaningful conversation. I tell you this is the worst part about being mentally ill. You feel so alone and want so much to have some company. But people don’t want to be tainted with the same brush. I have no confidence and I don’t remember how to make friends anymore. It all requires so much time and effort and money which I haven’t got.

High emotional commitment/low behavioural commitment

Male, age 28

I used to have colleagues at work years ago but I would not dream of calling them friends. I was a career man and never had time for friends and never miss this. Now I miss this even less. Maybe because I’ve never had friends I don’t know what I’d missed. I prefer my own company; I go out when I want to. A lot of the times I don’t have the energy. I wouldn’t want to make all kinds of efforts to start a relationship anymore.

Low emotional commitment/low behavioural commitment

Male, age 56

I used to have friends when I was a child. I remember hanging out with other children. I haven’t got friends for a while now. I have acquaintances; I see them when I go to the club. I just play darts, just keep it superficial. I don’t need friends emotionally, just people to chat with sometimes, nothing too deep. I talk to my brother and sister if I have a problem. I don’t trust people. My big fear is whether they will let me down. People are just out for what they can get. I’ve had money taken away from me before by people I liked. I got into big trouble because of it.

Low emotional commitment/high mistrust

Male, age 45

I don’t need people around me. I prefer to be on my own. I get uncomfortable and panicky when people are around. Not my best friend. He is alright. I can be with him for about an hour and then I start to find it hard to cope. I start thinking that maybe we will start to argue then it will be too much for me.

Fear of intimacy/avoidance of arousal

Male, age 50

Friendship network size

For the entire interviewed sample (n = 137), the mean number of friends was 1.57 (SD = 1.9, 95% CI mean = 1.25–1.89). 58 (42.3%) of the participants had no friends as defined above. Significantly more men (53.1%) than women (26.8%) had no friends (χ 2 = 13.517, df = 1, p = 0.000).

Of those without friends, 35 could think of no one at all, 16 mentioned acquaintances and similar weak-ties [22]. One said his support came from his ‘voices’. Four participants stated that they did not need anyone because they had family support, two participants felt no friends were needed because they had support from the community mental health nurse.

I don’t see anybody, only my CPN (community psychiatric nurse) once a fortnight. My brother looks after me. I don’t go out at all. I have meals on wheels. I don’t need to have any more from anybody.

Female, age 42

My father is my friend, we keep each other company. Neighbours I say hello to, but they are not friends. I don’t like too much noise; I like to be on my own with my dad.

Male, age 26

I have three friends, my drug pusher, he gives me speed, my Case Manager sees me every week and the shopkeeper, he gives me cigarettes on credit sometimes. I also have spirits coming to me, they visit at night and we talk. They are good friends, three of them.

Male, age 46

Quality of friendship network

Of the 79 participants who reported friendships, 75 named someone who had also experienced mental health problems. Most described levels of actual support received from their friends at the higher end of the possible range on the SOS with an average score of 10.7 (SD = 2.6) for emotional and 9.6 (SD = 2.4) for practical support (the theoretical maximum score being 14 for each domain) and there was little reported difference between these and the ideal support ratings that were only slightly higher on average [emotional 11.4 (SD = 2.3); practical 10.7 (SD = 2.3)]. Further detail collected through the SESS and semi-structured interviews confirmed the impression of predominantly positive social interactions, finding contact with friends to be warm, enjoyable and rewarding. A third of the participants mentioned some problems but in general these were outweighed by the positive benefits. There were no statistically significant differences between men and women in terms of any measure of the quality of the friendship.

Friends who also had mental health problems were said to be able to understand the participant’s experience and illness, and shared similar interests and activities, with ‘ready-made’ places to meet such as day centres.

I get on really well with my two friends. We see each other every day at the day centre. We don’t do much outside of that. We do the same activities, have lunch together and talk about the weather, the world. I generally feel very relaxed with them. We tried not to talk about deep emotional things, so we never get disagreeable with each other because we don’t get personal. We have a laugh most days. I am happy to have them as friends. It makes the Centre more interesting and makes me want to come more often.

Male, age 38.

Some friends fulfilled multiple roles, providing both emotional and practical support. These ‘multiplex’ relationships have been viewed as beneficial because they significantly increase available support [23] and this relates to overall satisfaction with one’s network and perceptions of support [24]. This is typically illustrated as follows:

I have one person I would call a really good friend. I met her at the hospital. Since discharge we’ve been there for each other. We meet regularly for lunch, just to catch up. She is there for me at the other end of the phone. She is like a sister to me. She lends me money if I am short and fags as well. If I feel depressed she cheers me up. I do the same for her.

Female, age 32

Avoiding direct confrontation by withdrawal appeared to be a means of reducing negative interaction and maintaining quality of relationships. 13 (16.5%) of participants used this strategy, as illustrated in the following quote:

I only have one friend. It is enough for me. Too many friends means too much gossip, I don’t need that. Rosie and I don’t do much. I don’t like too much noise or too much talking. I go to her most days after the day centre. She lives just up the road. I stay from 4.00 to 10.00 p.m. then I go home, take my tablets and go to bed. Most of the time she relaxes me, just having cups of tea and watch the box. There are times when she gets anxious and that makes me nervous as well. I can see it coming because she gets all worked up and red in the face. I just say my goodbye and keep away. I can’t say I have bad times with her, I just won’t let it happen; she is my ideal friend really.

Female, age 52

Impact of illness, handicap and stigma

There was no statistically significant association between having friends and age at first onset or subsequent duration of illness, number or length of hospitalisations during the previous 18 months. Participants without any friends had poorer clinical functioning than those with friends in terms of average PANSS positive (mean 16.5 SD = 6.6 vs. 13.1 SD 5.9 p < .002) and negative (mean 18.5 SD = 8.5 vs. 13.0 SD 7.5 p < .001) symptoms, GAF (mean 46.9 SD = 16.9 vs. 59.6 SD = 18.4 p < .001) and SBS score (mean 15.5 SD = 9.8 vs. 9.2 SD 8.0 p < .001). But they were also more likely to report feeling stigmatised [60% (35/58) vs. 39% (31/79) p < .02] and mistrustful of social encounters [91% (53/58) vs. 52% (41/79), p < .001]. Feelings that were only weakly and not significantly associated with current mental state. Nearly half of participants (48%, 66/137) said that they avoided social contact for fear of rejection on account of their illness.

My friends have moved on, all my uni [university] friends I no longer have contact. I had contacted them a few times but they don’t return my calls. They think I am silly and mad.

Female, age 25

People scare me. I feel they looked at me all the time. I stay in more because I can’t cope with all the hassle. I’ve never worked so I won’t know about prejudice in that sense. I do think that if you are mentally ill people think you are stupid and bad. I’d rather be without a leg sometimes.

Male, age 44

No overall association was found between friendship and medication use or reported side effects, although a number of individuals reported difficulty socialising because of drowsiness or fatigue associated with medication.

While a low level of emotional and behavioural commitment to friendship among those without friends would be expected, it is interesting to note that a third of those with friends also reported low levels of commitment and 72% (57/79) said they made little or no efforts to make new friends. Neither emotional or behavioural commitment were associated with current clinical state but like perceived stigma and mistrust appear to reflect much longer standing social consequences of the illness such as the lack of employment and leisure opportunities and bad experiences of efforts at socialising in the past.

I think people gossip behind your back anyway about anything that they find strange about you. I believe my illness has caused social limitations. For instance I can only go out when there are not many people about in case they talk about me. I was working in the civil service when I had my breakdown. Civil servants are well trained not to be overtly prejudiced. So I have no way of telling whether stigma existed then.

Female, age 54

Since I have been on medication I have felt better. I don’t hear voices no more. I have tried for years to make some friends because life is lonely. But where do I get the chance to do that? I can’t get a job, I am not really very confident in social places. I thought I go online to have a look but they are full of weirdos!

Female, age 48

I have to say that I am far more comfortable with people who have had experiences of mental health problems because you do share something and have something to talk about. I haven’t really been in society for many years and I am out of touch with a lot of things. I can’t hold a conversation with normal people. I can’t keep up with them. I sooner not bothered.

Male, age 40

Friendship and intimate sexual relationships

While as noted earlier, the focus of this paper is on non-kin, non-sexual relationships it is worth noting the close correlation of the two: those involved in sexual relationships were also more likely to have friends. Only 12 (7 men and 5 women) of the 58 participants without any friends had been involved in any sexual relationship and of these only two claimed a currently supportive, confiding and moderately intimate relationship.

Researcher and participant view of the presence of problems in friendship

The participant’s view of presence of friendship problems was obtained by questioning whether anything they had described or any other undisclosed issue was a problem in their friendship. The researcher’s view regarding the presence of a problem in this area was defined by the fact that the participant did not have one single friend or, in the case where there were friends, there was poor quality of social interaction rated according to SESS criteria (see above). There was a significant difference between the views of the participant and the researcher as to whether there was a problem or not (McNemar test 59.7, p < 0.001); the researcher being up to three times more likely to report a problem than the participant.

Discussion

Methodological considerations

We have some confidence that this was an almost complete geographical sample of people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in the area chosen for study [13]. Participants were chosen from multiple, cross-referenced sources including both primary and secondary care, and only a few declined to be interviewed. Furthermore, the number of participants was close to that expected from the best estimates for 1-year prevalence of schizophrenia [13, 25]. There may be under-representation of people who do not have contact with secondary mental health services and this group may experience a higher level of sex and relationship functioning than the sample studied. Whilst the homeless population was also excluded from this study, it is small and transient in the local town. The number of people with schizophrenia in this group is not known as they are often not in contact with secondary services and not registered with primary care. The choice of a minimum duration of illness of not less than 2 years ensures that only people with well-established diagnosis were included, but has the drawback of excluding patients with more recent onset.

We excluded partners in intimate relationships in the definition of ‘friends’, but this had has only a small effect on the size of friendship network in our sample. We make the distinction between friendship and intimate relationship while acknowledging that the former can be part of the latter. Friendship within an intimate relationship context is complex and can be influenced by numerous factors such as sex, financial and family considerations, unlike friendship in the social sense, which is voluntary and exists primarily for personal satisfaction and enjoyment, rather than the fulfilment of a particular task or goal [26].

Quality and size of friendship network

The study supports previous research showing that people with schizophrenia typically have impoverished social networks. We found a mean number of 1.57 friends. This is much smaller in number when compared with the general population in UK where the mean number for men is 10.6 and 7.4 for women [27]. The population survey covered 1,000 adults and used a self-definition of ‘friendship’. However, it used a postal questionnaire which may have overestimated the number of friends compared to our interview method, but this would be unlikely to explain the five- to seven-fold differences found. In our study sample, women have more friends than men. This is often assumed to be explained by the later onset of illness in women, allowing more opportunity for psychosocial skills to be developed though the age of onset or duration of disorder was not associated with the presence of friendships in our series. The men in our study do, however, report higher levels of mistrust, a greater fear of intimacy, and lower levels of emotional commitment than do the women. Even for the women in our sample, a fear of intimacy is much more common than that reported by general population samples, for example, in a sample of 400 Islington women (non-depressed, largely working class) only 17% showed such high levels of fear of intimacy [28].

Despite the fact that nearly 43% of participants were without friends, those who had them appeared to enjoy a good level of both emotional and practical support. Although the ideal support ratings were higher than that of the support actually received, this discrepancy was minimal. Considering the findings from Nelson et al. [29] it would appear that those participants who had friends were happy with the support they received despite the relatively small size of the friendship network.

Researcher and participant view

The researcher’s rating of the presence of problem was defined by the lack of friends, or in the case where there were friends, the degree of difficulties within the context of social interaction. The participants’ view is a subjective perception of whether they experience a problem or not. According to these criteria, over half of participants have a problem socially, but only one in ten perceived this as a problem. This finding goes against some studies that revealed people with serious mental illness ranked issues such as friendship higher on their list of needs than addressing specific symptoms [30]. It could be that not having friends is ‘ego-syntonic’—it fits in with the individual’s way of life. As shown in previous research, withdrawal from interaction with others can be a way of minimising stress and arousal levels [31]. The choice of not having friends could be a way of avoiding arousal caused by tensions and conflict inherent in any relationships. In this sense not having friends would not be experienced as a problem by the individual concerned, but an adaptive means of coping.

Clinical implications

Many rehabilitation programmes include interventions aimed at encouraging patients to socialise without a deep appreciation of what this demands of patients. The majority of social skills programmes, for example, tackle the problem of low behavioural commitment but can do little for people who express very little desire for socialisation. This study showed that many people with schizophrenia who have no friends do not perceive this as a problem. As clinicians we need to understand their situation, and explore the psychological factors that underpin this lack of motivation to have friends.

Previous theoretically sound models had specified that symptoms impact on social skills, which in turn influenced the size of social network and perceived social support. This study showed that there are other variables that need to be taken into consideration, such as intimacy, trust, commitment and stigma—and that these may be more important impediments to relationships than the symptoms of illness. A greater specificity in the application of psychological intervention is needed to look at these critical elements, aside from just social skills training. Practical help may be needed to reduce the barriers caused by the lack of behavioural commitment. Social inclusion and anti-discriminatory work is important in helping patients develop social support towards recovery.

Of the 79 participants with friends, 75 named someone amongst fellow service users, who they met at hospitals or day centres. They appreciate their shared experiences and mutual support. This interaction also motivates participants to attend day services and socialise with others. It is therefore important to continue with this service provision in future planning.

Conclusion

Consistent with previous research, people with schizophrenia have a smaller social network of friends than that of the general population. However, the quality of these friendships is generally good and highly valued. There are psychological factors that impact upon motivation and skills to form and maintain social relationships, and not having friends may not be perceived to be a problem by the individual concerned. Psychosocial intervention programmes need to take into account these factors. Service provision needs to take into account the importance of day centres in the encouragement of a more active social life for this group of service users.

References

Goldberg R, Rollins A, Lehman A (2003) Social network correlates among people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J 26(4):393–404

Amminger G, Pape S, Rock D (1999) Relationship between childhood behavioural disturbance and later schizophrenia in the New York High Risk Project. Am J Psychiatry 156:525–530

Green M, Kern R, Braff D, Mintz J (2000) Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 26(1):119–136

Halford W, Hayes R (1994) Social skills in schizophrenia: assessing the relationship between social skills, psychopathology and community functioning. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 30(1):14–19

Mueser K, Bellack A (1998) Social skills and social functioning. In: Mueser K, Tarnier N (eds) Handbook of social functioning in schizophrenia. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Wing JK, Brown GN (1970) Institutionalism and schizophrenia: a comparative study of three mental hospitals 1960–1968. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hemsley D (1978) Limitations of operant procedures in the modification of schizophrenic functioning: the possible relevance of studies of cognitive disturbance. Behav Anal Modif 2:165–173

Nuechterlein K, Dawson M (1984) A heuristic vulnerability/stress model of schizophrenic episodes. Schizophr Bull 10:300–312

Thornicroft G (2006) Shunned: discrimination against people with mental illness. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Marwaha S, Johnson S (2004) Schizophrenia and employment: a review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39(5):337–349

Wright P (1984) Self-referent motivation and the intrinsic quality of friendship. J Soc Pers Relatsh 1:115–130

Hinde R (1997) Relationships: a dialectical perspective. Psychology Press, UK

Harley E, Boardman J, Craig T (2010) Sexual problems in schizophrenia: prevalence and characteristics. A cross sectional survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45:759–766

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association

Kay S, Fisbein A, Opler L (1987) The positive and negative symptom scale in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13:261–276

Endicott J, Spitzer R, Fleiss J, Cohen J (1976) The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 33:766–771

Wykes T, Sturt E (1986) The measurement of social behaviour in psychiatric patients: an assessment of the reliability and validity of the SBS schedule. Br J Psychiatry 148:1–11

O’Connor P, Brown G (1984) Supportive relationships: fact or fancy? J Soc Pers Relatsh 1:159–195

Power M, Champion L, Aris S (1988) The development of a measure of social support: The Significant Others (SOS) Scale. Br J Clin Psychol 27:349–358

Link B, Phelan J (2001) Conceptualising stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 27:363–385

Scambler G (1998) Stigma and disease: changing paradigms. Lancet 352(9133):1054–1055

Granovetter M (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 78:136080

Hamer M (1981) Social supports, social networks and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 7(c):45–57

Baker F, Jodrey D, Intagliata J (1992) Social support and quality of life of community support clients. Community Ment Health J 28(5):397–411

Goldner E, Hsu L, Somers J (2002) Prevalence and incidence studies of schizophrenia disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry 47:833–843

Wiseman J (1986) Friendship: bonds and binds in a voluntary relationship. J Soc Pers Relatsh 3:191–211

Wighton K (2007) How many close friends do you have?. The Times (United Kingdom) 21.4.2007

Brown G, Andrews B, Harris T, Adler Z, Bridge L (1986) Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychol Med 16:813–831

Nelson G, Hall G, Squire D, Walsh-Bowers R (1992) Social network transactions of psychiatric patients. Soc Sci Med 34:433–443

Coursey R, Keller A, Farrell E (1995) Individual psychotherapy and persons with serious mental illness: the client’s perspective. Schizophr Bull 21:283–301

Corin E, Lauson G (1992) Positive withdrawal and the quest for meaning: the reconstruction of experience among schizophrenia. Psychiatry 55:226–281

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the service users, carers and clinicians of Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust who gave me their time and effort to participate in this research project.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harley, E.WY., Boardman, J. & Craig, T. Friendship in people with schizophrenia: a survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47, 1291–1299 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0437-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0437-x