Abstract

Purpose

The concept of the suicidal process implies a progression from behaviour of relatively low intent to completed suicide. Evidence from the literature has given rise to the speculation that the age of onset of an early form of the suicidal process may be associated with the ultimate seriousness of suicidal behaviour. This study was designed to test the hypothesis that early onset of the first stage of the suicidal process, a wish to die, is associated with increases in the ultimate position along the suicidal process dimension.

Methods

Questions on the appearance and timing of suicidal process components (a death wish, ideation, plan, or attempt) were embedded in a telephone survey on mental health and addictions in the workforce. Records of those that had experienced suicidal behaviour were examined for the effects on the age of onset of the first death wish as a function of the level of severity of suicidal behaviour, gender, and depression.

Results

The findings showed that increases in suicidal intent were associated with lowered age of the first death wish. This pattern held true for depressed and non-depressed persons alike.

Conclusions

The results support the notion that the early onset of a supposed precursor of suicidal behaviour, a death wish in this case, adds to its ability to portend more serious problem levels in later stages of life. Furthermore, mood operates independently in its association with the timing of such suicidal behaviour, suggesting that the effect of a relatively youthful appearance of a wish to die cannot be explained by early onset depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicidal behaviour is commonly viewed as comprising an orderly progression that begins with occasional thoughts of death and ends at some point along a single continuum, the last position of which is completed suicide [1]. Similarly, movement from a death wish through to a suicide attempt has been interpreted as a hierarchy of intent [2], and a number of authors have discussed this under the general concept of “the suicidal process” [3–5]—the term adopted here.

The conception of the suicidal process implies that age of onset is earlier and less severe for death wishes and later and more serious for suicide attempts. Early age of onset for particular psychiatric disorders is generally associated with greater severity later in life. For example, onset of depression during childhood increases the likelihood of depressive recurrence [6] and predicts social and other problems of life [7, 8]. Furthermore, relatives of persons with early onset of depression have higher morbidity than those with a later onset [9–11]. Within the suicide process, higher levels of severity are associated with earlier onset of depression [12], suggesting that the early appearance of a condition that shows a strong association with suicide predicts its severity. This raises the question of whether the age of the beginnings of the suicidal process itself has an effect on the seriousness of one’s future level of suicidality.

The suicidal process may not, however, prove to be so orderly. For example, some findings indicate that the process would be better characterized as fluctuating, rather than smooth [13] while others suggest that it varies according to culture [14], and there may be three types of suicidal process—not one [15].

Furthermore, there is variation in definitions across studies. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication used a definition that sets “serious” ideation as an inclusion criterion [16, 17], whereas the earlier Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey [18] made no mention of seriousness, indicating that any level of suicidal thought was to be considered. This distinction will undoubtedly produce differences in prevalence estimates, and it does so without addressing the significance of, for example, suicidal thoughts that occur “fleetingly” and might thus be perceived as being unimportant. Although many self-help information sources (e.g. Web MD) suggest that such early forms of suicidal behaviour are not necessarily momentous, the argument has been made that even distal precursors can have meaningful predictive value and should not be dismissed out of hand [12].

This study was designed to examine the reported order of appearance of four stages of the suicidal process (death wishes, ideation, plans, and attempts) and to determine whether variation in the age of onset of the earliest stage in the process (a death wish) would differ in accord with the seriousness of the level of subsequent stages. It has been known since the work of Shneidman and Farberow [19] that males show higher rates of completed suicide and females show a higher frequency of attempts (other forms of parasuicidal behaviour show mixed results [20–22]), and that the age of onset of depression has been implicated in suicidal behaviour [12], thus leading to the inclusion of measures of gender and major depression in the analysis.

Methods

Participants

Albertans who were in the workforce during the 12 months preceding the survey were eligible for inclusion. The survey questionnaire was administered via telephone by professional interviewers during a 13-week period from late August 2009 to late November 2009. There were 2,817 Albertans who completed the survey. The overall response rate was 42.3% of those contacted, but it should be noted that it improved throughout the course of data collection, ranging from 28.8 and 27.0% for the first 2 weeks to 72.5 and 72.8% for the last 2 weeks. Since there was no statistically significant variation in the distributions of marital status, education, household income, or gender over this time period (age, although significant, showed no discernible trend) [23], it can be assumed that the effective rate is near to the 70% level. The proportion of female respondents was 60.2%, and the age at interview ranged from 18 to 80 years (mean = 45.4 years, SD = 11.8).

Survey instrument

Items tapping the suicide process were embedded in an investigation of workforce mental health and addictive behaviours that was designed to be administered by lay interviewers. The interviewers were employed by a research firm and had received training in survey administration, relationships with respondents, ethics, and referrals, but not in clinical matters generally. The suicidality questions were adapted from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule [18], and are similar in nature to items introduced in an epidemiologic study by Paykel and his colleagues [24]. The purpose was to create a scale representing meaningful increments in suicidal intent. Note that the respondents were asked to respond in the affirmative if the behaviour in question took place, irrespective of the seriousness of the event. The resultant questions, respectively, representing a death wish (without the self-harm componentFootnote 1), suicidal ideation (thoughts of taking one’s one life), making a plan, and making an attempt, are as follows:

-

1.

Has there ever been a period when you felt like you wanted to die?

-

2.

Have you felt so low you thought of committing suicide?

-

3.

Have you ever made definite plans to commit suicide (even though you did not actually make an attempt)?

-

4.

Have you ever attempted suicide?

Each respondent was also asked to indicate the age at which each event first took place.

A major depressive episode (MDE) was diagnosed as present or absent on the basis of response to items adopted from the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [25]. This measure was based on DSM-IV criteria with the caveats that (1) the suicidal behaviour symptom was not considered in order to avoid artificially inflating the correlation between suicidality and depression, and (2) as is the custom, depression due to grief was excluded.

This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta.

Statistical analysis

A univariate general linear model (GLM) analysis was conducted on the mean age of the first death wish with three independent variables; suicidal intent, presence or absence of MDE, and sex. A Chi-square test was used to examine sex differences in the reporting of suicidal intent.

A supplementary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc test for trend (linear and non-linear) was undertaken to examine the effect of the age at interview on suicidal level. This, since relatively higher age of onset values could not, of course, exceed a respondent’s own age at the time of the interview, thus providing the potential for bias in an overall analysis. Respondents were assigned to one of three groups based on age of interview, using percentiles of 33.3 and 66.7% as split values to approximate equal group sizes. The optimal selections proved to be 18–39 years (n = 113), 40–50 years (n = 133), and 51–80 years (n = 126). All analyses were conducted with the use of SPSS 14.0.

Results

Overall, 439 (15.7%) of the respondents showed some form of suicidal behaviour (one or more of either a death wish, suicidal thought, plan, or attempt). This is at the low end of lifetime prevalence estimates noted in a number of reviews [1, 14, 26, 27]. Furthermore, it is less than one-third of the 52% reported for university students in the same Canadian province using the same questions, but conducted several years earlier [28]. Notably, however, the distribution across the suicidal process proved to be quite similar. This finding of a descending prevalence with increasing severity of suicidal behaviour (Table 1, row 1) has been reported in a number of community surveys [24, 29–32]. The second row in Table 1 shows the mutually exclusive categories defined by the criterion of the “highest” level of suicidal behaviour (i.e. most serious). These categories comprise the groupings along the severity dimension of the suicidal process. From this, we can see that of the 400 with a death wish, 135 did not move to a higher level, but 265 (66.3%) did progress to at least the ideation stage. Similarly, 84 of the 306 ideators (27.5%) moved on to a plan or attempt, and 43.3% of the planners (26 of 60) made an attempt.

The ANOVA summary is included in Table 2. Note that the analysis includes only those respondents who had experienced a death wish (n = 400) minus those with values missing on any of the independent variables. This produced a sample size for the ANOVA of 375 persons. The use of a definition of MDE that ignored the presence or absence of suicidal symptoms reduced the number of identified cases by only five (163–158).

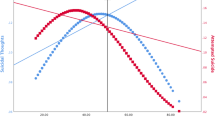

Of primary importance to our main hypothesis, the significant main effect for suicidal level indicates that the age of onset of the first death wish is negatively correlated with the intensity of parasuicidal behaviour (Fig. 1). That is, the average (median) age of onset ranged from just under 16.9 years for those who had made an attempt through to 29.8 years for those who exhibited a death wish without other parasuicidal behaviour. A post-hoc polynomial test produced a significant linear trend (contrast = −7.07, SE = 1.94, p < .001), but no significant deviations from linearity. This unfettered linear relationship indicates that as the age of onset increases, the level of seriousness of the parasuicidal behaviour shows an orderly decrease.

Although females were more likely to have reported suicidal behaviour than were males (18.1 vs. 12.1%; relative risk = 1.50; χ 2 = 22.28, df = 4, p < .001), sex did not prove to have a significant influence on the age of first death wish, either alone or in interaction with the level of suicidal behaviour.

Depression did show a statistically significant main effect, with depressed persons showing a higher age of death-wish onset (about 3 years more). Importantly, depression did not show a statistically significant interaction with any other variable. Notably, the linear trend across the suicidal process held equally for both depressed and non-depressed persons.

Figure 2 reflects the statistically significant finding that greater age at interview was associated with a relatively older age of first death wish (F 2,360 = 38.45, p < .001). However, the interaction between level of suicidal behaviour and age at interview was not significant (F 6,360 = 1.14, p = .34), indicating that the just-noted relationship between the intensity of suicidal behaviour and the reported age of first death-wish holds true across all age groups, albeit at differing base levels. Note that the 40–50 age group’s mean for “Plan” is based on only three respondents—the likely explanation for this aberrant value (the next lowest cell size was 11). Nonetheless the linear trend lines for all three age groups are near to parallel.

Discussion

Although the literature has indicated that the suicidal process does not always represent a strict linear progression when examined closely [13–15], the findings here did not support that kind of concern. The results clearly indicate that lower age of onset of prodromal suicidal behaviour is associated with increased severity along the continuum of the suicidal process. Furthermore, this trend does not vary when differences in the age of interview are examined. Thus, it is not just that the appearance of indicators of suicidal behaviour, like a death wish, are a cause for concern, but also that early appearances of such behaviours should increase our apprehensive watchfulness to a considerably greater extent. Like early onsets among mental health conditions (as noted above) and other problem behaviours such as substance use [33–35] and conduct disorder [36], early thoughts of death can, in theory, be expected to presage a greater likelihood of a difficult future, including a progression to more serious levels of suicidal behaviour in upcoming years.

It is interesting that although early onset of depression has been associated with the severity of suicidal behaviour [12], it cannot explain the findings here since persons who have not experienced major depression show a similar death-wish gradient across the suicidal process. This is thus somewhat surprising, as is the finding that depressed respondents showed death-wish onset at a later age than did those who were not depressed. Unfortunately, the issue cannot be authoritatively addressed here since age of depressive onset was not collected in this study, thus suggesting a need for a more definitive future investigation.

In any case, the data at hand indicate that these two factors, early onset death-wish and early onset depression, appear to operate independently in, perhaps, an additive fashion. Remembering that age of onset data was collected retrospectively, the correlation between the age of the respondents at the time of interview and the age of first remembered death wish may merely represent differences in recall that are due to some aspect of aging. An alternative theory, however, is that we are witnessing a period effect where more recent generations are showing signs of disturbance earlier in life. There is some evidence that a generational effect has been found for major depression (but not bipolar disorder) with large increases in overall prevalence being shown over the last few decades of the twentieth century [37, 38].

The comparatively low prevalence of suicidal behaviour in the sample studied here may reflect the likelihood of greater stability among those engaged in the workforce versus those who are not [39]. This cannot be determined from the findings in our study, but in a large community sample in the same province, those who were unemployed showed a much higher likelihood of a suicide attempt than those who were working (relative risk = 3.85) [40].

Gender differences in suicide attempts notwithstanding, the extent that the suicidal levels have some relevance to life’s journey suggests that men and women follow the same pathway, excepting the still-remaining final step, completed suicide, where men predominate.

Potential bias due to the retrospective nature of the survey would ordinarily lead to suggestions for longitudinal studies, but asking children about suicidal behaviour carries some possible danger. This issue is nonetheless important enough to justify asking children about their position along the suicidal process, but after seeking out the most safe and unobtrusive measures that are effective. It is useful to remember the admonishment of Mishara [41], that it is naïve to think that children do not know about suicide, with the relevant facts being known by most 5- to 7-year-old and by almost all who are older than that.

As a final note, wishing for one’s death has been characterized as a “fleeting” event, and thus often not treated with a great deal of seriousness [42, 43], and, as noted above, only “serious” ideation was recorded in the American National Comorbidity Survey Replication [16, 17]. It is perhaps advisable to note that a single thought of this nature indicates a very high level of distress at the time of its appearance and it portends an alteration in attitude and coping behaviour—a shift in one’s life course. Undoubtedly, some will adapt in a positive way and some will not. Thus, an expression of a wish to die by a child may indicate a window of opportunity whereby intervention can take place prior to the choice of a maladaptive pathway leading to higher intensity forms of suicidal behaviour such as a suicide attempt [41, 43].

Notes

A death wish, by definition, does not include thoughts of suicide and thus it is not clear that it should be discussed as suicidal behaviour. However, it will be retained as such since, at worst, it is prodromal to suicidal behaviour and contemporary convention has it firmly planted in the suicidal process.

References

Angst J, Degonda M, Ernst C (1992) The Zurich study: XV. Suicide attempts in a cohort from age 20 to 30. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 242:135–141

Mościcki EK (1989) Epidemiologic surveys as tools for studying suicidal behavior: a review. Suicide Life Threat Behav 19:131–146

Portzky G, Audenaert K, van Heeringen K (2005) Adjustment disorder and the course of the suicidal process in adolescents. J Affect Disord 87:265–270

Runeson BS, Beskow J, Waern M (1996) The suicidal process in suicides among young people. Acta Psychiatr Scand 93:35–42

van Heeringen K, Hawton K, Williams JMG (2000) Pathways to suicide: an integrative approach. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K (eds) The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. Wiley, New York, pp 223–234

Kovacs M, Feinberg T, Crouse-Novak M, Paulauskas S, Pollock M, Finkelstein R (1984) Depressive disorders in childhood. II. A longitudinal study of the risk for a subsequent major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 41:643–649

Kandel DB, Davies M (1986) Adult sequelae of adolescent depressive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:255–262

Rao U, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Dahl RE, Williamson DE, Kaufman J, Rao R, Nelson B (1995) Unipolar depression in adolescents: clinical outcome in adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:566–578

Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H (1986) Recurrent and nonrecurrent depression: a family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:1085–1089

Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Merikangas KR, Leckman JK, Prusoff BA, Caruso KA, Kidd KK, Gammon GD (1984) Onset of major depression in early adulthood: increased familial loading and specificity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 41:1136–1143

Weissman MM, Merikangas KR, Wickramaratne P, Kidd KK, Prusoff BA, Leckman JK, Pauls DL (1986) Understanding the clinical heterogeneity of major depression using family data. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:430–434

Thompson AH (2008) Younger onset of depression is associated with greater suicidal intent. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43:538–544

Wyder M, De Leo D (2007) Behind impulsive suicide attempts: indications from a community study. J Affect Disord 104:167–173

Bertolote JM, Fleishmann A, De Leo D, Bolhari J, Botega N, de Silva D, Thanh HTThi, Phillips M, Schlebusch L, Varnik A, Vijayakumar L, Wasserman D (2005) Suicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: the WHO SUPRE-MISS community survey. Psychol Med 35:1457–1465

Fortune S, Stewart A, Yadav V, Hawton K (2007) Suicide in adolescents: using life charts to understand the suicidal process. J Affect Dis 100:199–210

Kessler RC, Merikangas KR (2004) The national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 13(2):60–68

Kessler RC (2006) National comorbidity survey: replication (NCS-R), 2001–2003 [Computer file]. Conducted by Harvard Medical School, Department of Health Care Policy/University of Michigan, Survey Research Center. ICPSR04438-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [producer and distributor], 2006-06-07. http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/. Accessed 13 Oct 13 2006

Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL (1981) NIMH diagnostic interview schedule. NIMH Division of Biometry and Epidemiology, National Institute of Mental Health, Washington

Shneidman ES, Farberow NL (1961) Statistical comparisons between committed and attempted suicides. In: Farberow NL, Schneidman ES (eds) The cry for help. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 19–47

Kuo W, Gallo JJ, Tien AY (2001) Incidence of suicidal ideation and attempts in adults: the 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychol Med 31:1181–1191

Thomas HV, Crawford M, Meltzer H, Lewis G (2002) Thinking life is not worth living. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 37:351–356

Vilhjalmsson R, Kristjansdottir G, Sveinbjarnardottir E (1998) Factors associated with suicide ideation in adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33:97–103

Thompson AH, Jacobs P, Dewa CS (2011) The Alberta survey of addictive behaviours and mental health in the workforce: 2009. Institute of Health Economics, Edmonton

Paykel ES, Myers JK, Lindenthal JJ, Tanner J (1974) Suicidal feelings in the general population: a prevalence study. Br J Psychiatry 124:460–469

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier L, Harnett-Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC (1998) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 22(Suppl 20):22–33

Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, Karam EG, Lee CK, Lellouch J, Lepine JP, Newman SC, Rubio-Stipek M, Wells JE, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen HU, Yeh EK (1999) Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychol Med 29:9–17

Welch SS (2001) A review of the literature on the epidemiology of parasuicide in the general population. Psychiatr Serv 52:368–375

Thompson AH (2010) The suicidal process and self-esteem. Crisis 31:311–316

De Leo D, Cerin E, Spathonis K, Burgis S (2005) Lifetime risk of suicide ideation and attempts in an Australian community: prevalence, suicidal process, and help-seeking behaviour. J Affect Disord 86:215–224

Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE (1999) Prevalence of risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:617–626

Mościcki EK, O’Carroll P, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Roy A, Regier DA (1988) Suicide attempts in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Yale J Biol Med 61:259–268

Rancans E, Lapins J, Salander Renberg E, Jacobsson L (2003) Self-reported suicidal and help-seeking behaviours in the general population in Latvia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38:18–26

Mayes LC, Suchman NE (2006) Developmental pathways to substance abuse. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D (eds) Developmental psychopathology, vol 3. John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp 599–619

Wolfe DA, Mash EJ (2005) Behavioral and emotional disorders in adolescents: nature assessment and treatment. The Guildford Press, New York

Oman RF, Vesely S, Aspy CB, McLeroy K, Rodine S, Marshall L (2004) The potential protective effect of youth assets on adolescent alcohol and drug use. Am J Public Health 94:1425–1430

Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT (1998) Conduct problems in childhood and psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood: a prospective study. J Emot Behav Disord 6:2–18

Seligman MEP (1989) Research in clinical psychology: why is there so much depression today? In: Cohen IS (ed) The G. Stanley Hall lecture series 9. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 65–96

Cross-National Collaborative Group (1992) The changing rate of major depression: cross-national comparisons. JAMA 268:3098–3105

Li CY, Sung FC (1999) A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occup Med 49(4):225–229

Bland RC, Stebelsky G, Orn H, Newman SC (1988) Psychiatric disorders and unemployment in Edmonton. Acta Psychiatr Scand 77(Suppl 338):72–80

Mishara B (1999) Conceptions of death and suicide in children ages 6–12 and their implications for suicide prevention. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 29(2):105–118

Gliatto MF, Rai AK (1999) Evaluation and treatment of patients with suicidal ideation. American Family Physician 57(6, March 15), pp 1500–1513. http://www.aafp.org/afp/990315ap/1500.html/. Accessed 27 Apr 2011

McAuliffe CM (2002) Suicidal ideation as an articulation of intent: a focus for suicide prevention? Arch Suicide Res 6:325–338

Acknowledgments

Data collection for the base study that included the questions used here was conducted under the terms of a contract between the Addiction and Mental Health section of Alberta Health Services (the sponsor) and the Institute of Health Economics, Edmonton, Canada. Interviewing and data assembly were completed by a private research firm, Malatest and Associates. We wish to thank the members of the project’s Advisory Committee for their much-appreciated input.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, A.H., Dewa, C.S. & Phare, S. The suicidal process: age of onset and severity of suicidal behaviour. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47, 1263–1269 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0434-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0434-0