Abstract

Purpose

To describe the prevalence of and the risk factors for poor mental health in female and male Ecuadorian migrants in Spain compared to Spaniards.

Method

Population-based survey. Probabilistic sample was obtained from the council registries. Subjects were interviewed through home visits from September 2006 to January 2007. Possible psychiatric case (PPC) was measured as score of ≥5 on the General Health Questionnaire-28 and analyzed with logistic regression.

Results

Of 1,122 subjects (50% Ecuadorians, and 50% women), PPC prevalence was higher in Ecuadorian (34%, 95% CI 29–40%) and Spanish women (24%, 95% CI 19–29%) compared to Ecuadorian (14%, 95% CI 10–18%) and Spanish men (12%, 95% CI 8–16%). Shared risk factors for PPC between Spanish and Ecuadorian women were: having children (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.4–6.9), work dissatisfaction (OR 4.1, 95% CI 1.6–10.5), low salaries (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.1–5.9), no economic support (OR 1.8, 95% CI 0.9–3.4), and no friends (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1–4.2). There was an effect modification between the nationality and educational level, having a confidant, and atmosphere at work. Higher education was inversely associated with PPC in Spanish women, but having university studies doubled the odds of being a PPC in Ecuadorians. Shared risk factors for PPC in Ecuadorian and Spanish men were: bad atmosphere at work (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.3–4.4), no economic support (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.3–9.5), no friends (OR 2.5, 95% CI 0.9–6.6), and low social support (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.9–2.9), with effect modification between nationality and partner’s emotional support.

Conclusions

Mental health in Spanish and Ecuadorian women living in Spain is poorer than men. Ecuadorian women are the most disadvantaged group in terms of prevalence of and risk factors for PPC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health problems have been described to be more common in economic migrants compared to the population of the host countries [1–4]. The development of mental disorders has been attributed to the inability to meet the expectations set prior to the migration, in spite of good health on arrival. Economic migrants face adverse economic situations, poor working conditions, discrimination and lack of social integration, all of which are the risk factors for mental diseases [1, 5–8]. Women, half of worldwide economic migrants, have been reported to have higher rates of affective mental disorders than men [8–10]. These gender differences have been attributed to the differential exposure to a higher number of stressors. These stressors operate both in family life—women are the primary caregivers for children, the sick and the elderly—as well as in the social sphere, where women have poorer access to quality employment and lower salaries [9–13]. There is also some evidence that the prevalence of and risk factors for depressive and anxiety disorders differ between male and female migrants of the same geographical origin [4, 14–17].

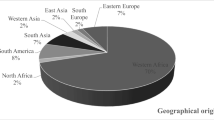

Over the last decade Spain has experienced a rapid increase in economic migrants. Ecuadorians accounted for about 20% of the foreigners from outside the European Union in 2004 [18]. Half of Ecuadorians in Spain are women who have either initiated the migration themselves or have followed their husbands. The migration process affects gender roles; women become primary income-earners and power relations are modified. The main avenue for integration into the Spanish labour market for female immigrants is the domestic work and caring for children and the elderly—a sector with high levels of irregular employment, low salaries, loneliness, and loss of social status. Male immigrants typically work in the agriculture and building sectors, both of which have high levels of job insecurity, but higher salaries.

Publications reporting population-based estimates of prevalence of mental health problems in migrants are scarce. So far, no such estimates have been published in Spain. We aim to describe the prevalence of and the risk factors for poor mental health, measured by the GHQ-28, in a probabilistic sample of female and male Ecuadorian migrants living in Spain, compared to the Spanish population of the same sex. We also aim to test if, for both women and men, established risk factors for poor mental health are similar for Spaniards and Ecuadorians.

Methods

A population-based home survey was conducted in 33 areas of residence within four regions in Spain (Alicante, Almería, Madrid, Murcia) from September 2006 to January 2007. These regions were chosen due to the high influx of migrants, and the 33 areas of residence were selected to reflect the variability in immigration density. Details of the study methodology have been published elsewhere [19]. A probabilistic sample of 1,188 adults aged 18–55 was requested from the civil registries allowing for an equal number of men and women, Spaniards and Ecuadorians. We excluded people over 55 years of age since most economic migrants tend to be young, in response to the demands of the labour market. The definition of Spaniards and Ecuadorians was based on the nationality. A second sample was drawn to compensate for invalid addresses, unavailable contacts and refusals. To minimize non-response bias, personal letters were sent to the potential participants informing them about the scientific nature of the study. A 10-euro token (phone card for Ecuadorians and petrol voucher for Spaniards) was given to each participant. Ecuadorians were visited by Latin-American interviewers, mostly women. Interviewers were carefully trained for this study; this training was supervised by the research team. A minimum of two documented visits at different times were made before moving to the next candidate. The sampling frame and field work strategy was planned and supervised in accordance with the results of a pilot study conducted in January–February 2006. A detailed description of the pilot study results has been published previously [19]. Briefly, the pilot helped us to test the feasibility of obtaining the desired sample, the acceptability and comprehension of the questions, and the internal validity of the scales. Based on the results, changes were made in the population selection strategy, choice of compensation token for Spaniards, the order and content of some questions, and duration of interview.

The overall response rate (completed interviews/completed + refusals) was 61%; 53% for Spanish men and 57% for Spanish women, and 69% for Ecuadorians (69% in both men and women) [19]. Median duration of the interview was 20 min for Spaniards (82 questions) and 35 min for Ecuadorians (100 questions). The outcome variable, possible psychiatric case (PPC), was defined as a score of five or more on the Spanish version of the 28-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) [20] validated in Spain [21] using the GHQ coding scheme. The 4/5 cut-off point was selected because we were screening in the general population, where the prevalence of PPC is lower than that in a clinical setting. The GHQ-28 is a mental health screening tool consisting of four sub-scales that capture recent changes in the somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression and social functioning, which has been extensively used and validated in many parts of the world. We collected the information on the following socio-demographic characteristics: civil status, number of children, family structure and education. Social support was measured by the Duke scale [22], validated in Spain by Bellón et al. [23], and categorized in terciles. Social network diversity was determined by asking about number of friends, contact with neighbors and work colleagues, and participation in religious and non religious associations. Emotional support from partner was measured based on five questions, answered on a Likert scale, which inquired about (1) the possibility of talking about problems, (2) receiving support and understanding when needed, (3) receiving enough affection, (4) sharing responsibilities, and (5) being treated with respect. The existence of a confidant was assessed by asking: “Is there a person special to you, with whom you can share your worries and feelings and whom you can trust?”, economic support was evaluated by the question “Is there someone who could lend you 100€ in case of need?”, and financial strain by “How would you rate your difficulties in making ends meet each month using your monthly income?” which was answered on a 5-item Likert scale. We inquired separately about individual and family unit income related to the national minimum wage (NMW). Subjects were asked about their employment and type of contract, and about work satisfaction and atmosphere using a 5-item Likert scale.

Sample size calculations were based on different estimates of the prevalence of PPC (10–35%), with precision ranging from 2 to 5%, alpha error of 5%, and design effect of 1.5. Ethics approval was obtained.

Statistical analyses

Separate analyses for Ecuadorian and Spanish men and women were conducted comparing proportions and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Multiple logistic regression was used to study the relationships between PPC and the explanatory variables in men and women. Within each sex, the interactions between the nationality and the risk factors for PPC were evaluated. We used likelihood ratio tests and Wald tests to derive p values. A significance level of 0.15 was chosen to select the variables to be entered in the multivariate logistic regression model. Backward procedure methods were used, and the best models were chosen comparing maximum likelihood values through Log Likelihood Ratio tests (LRtest). Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with robust estimates of confidence intervals at 95% were computed assuming the correlation between the subjects within each area of residence and independence between subjects from different areas of residence. The software used was Stata (Version 10.0, College Station, TX).

Results

Of 1,144 subjects interviewed; 2 had no information on the outcome variable and 20 were over 55 years, leaving a final sample of 1,122 people: 50% women and 50% Ecuadorians. Descriptive characteristics of the population are presented in Table 1 stratified by sex and nationality. Women, especially Ecuadorians, reported a higher prevalence of known risk factors associated with poor mental health (Table 1). Spanish parents were more likely to live with their children (96% of women and 94% of men) compared to Ecuadorians (80% of women and 71% of men).

The prevalence of PPC was higher in Ecuadorian (34%, 95% CI 29–40%) and Spanish women (24%, 95% CI 19–29%) compared to Ecuadorian (13%, 95% CI 10–18%) and Spanish men (12%, 95% CI 8–16%). No statistically significant interaction was seen between sex and nationality for the prevalence of PPC (p = 0.23). However, while Ecuadorian men did not have a higher prevalence of PPC compared to Spanish men (OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.7–1.9), Ecuadorian women had higher odds of PPC than Spanish women (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.4). Table 2 describes the PPC prevalence for each of the explanatory variables stratified by sex and nationality.

Multivariate analyses of risk factors associated with PPC in women are presented in Table 3. There were shared risk factors for PPC between Spanish and Ecuadorian women, such as having children, being dissatisfied at work, having low salaries, not having friends, and lacking economic support. Having children, both in women who live alone (single, separated, divorced, widowed) or in those who live with a partner, was a risk factor for PPC. Being dissatisfied at work was associated with a fourfold increase in the odds of PPC. Economic difficulties, measured as earning a salary below the NMW, were also a risk factor for PPC. Lacking economic support was associated with the higher odds of PPC, but this result was of marginal statistical significance. There was effect modification on the odds of PPC between the nationality and educational level (p = 0.0025), lacking a confidant (p = 0.066), participating in associations (p = 0.11), and atmosphere at work (p = 0.16), the latter three are of borderline statistical significance. While higher education was inversely associated with PPC in Spanish women, having university studies doubled the odds of being a PPC in Ecuadorian women, although this association was not statistically significant given the small number of Ecuadorian women in this category. Lacking a confidant increased the odds of PPC by five in Spanish women, but had no effect on Ecuadorians. Participating in associations was associated with higher odds of PPC in Ecuadorian but not Spanish women, and bad atmosphere at work was associated with a fivefold increase in the odds of PPC in Spanish women.

There were also some shared risk factors for PPC between Ecuadorian and Spanish men (Table 4). Those with a bad atmosphere at work and those with unknown values in this variable had a twofold increase in the odds of PPC. Having no economic support, no friends and lacking social support were the risk factors for PPC. There was effect modification for the odds of PPC between nationality and emotional support from the partner (p = 0.001), and while the lack of this was associated with higher odds of PPC in Spaniards, it was not so in Ecuadorians.

Discussion

Mental health in Spanish and Ecuadorian women living in Spain is poorer compared to that of men of the same nationalities. Among women, Ecuadorians fare worse than Spaniards. Risk factors for poor mental health differ by sex and nationality, both in their prevalence and in the magnitude of their association. Being Ecuadorian behaves as an effect modifier for some known risk factors for poor mental health in both sexes. Spanish men are notable for having the lowest prevalence of risk factors for poor mental health, while Ecuadorian women are overexposed to established risk factors in nearly all spheres of their live. Spanish women and Ecuadorian men lie in between these two extremes. Spanish women share the family burden and lower salaries with Ecuadorian women, but have better social and emotional support networks than Ecuadorian men. Ecuadorian women emerge as the most disadvantaged group; a very high proportion of these women have children, perceive low emotional support from their partners, have low social support and the poorest social diversity network. Ecuadorian women have the lowest salary, highest level of financial strain, lowest economic support, and highest dissatisfaction at work.

The proportion of Spanish women who have children was lower than in Ecuadorians and closer to Spanish men. Motherhood and parenthood have different associations with mental health: having children increased the odds of being a PPC by twofold in women but not in men, as previously reported [24]. Some authors have reported that poor mental health in these women is associated with economic vulnerability and lack of support [24–27]. In our study, being married was associated with poor mental health in univariate analyses in women, but not in the multivariate analyses that took into account the presence of children.

Socio-economic conditions played a major role as mental health determinants. We found major salary inequalities between men and women, irrespective of their nationality. While up to 24% of Spanish and 44% of Ecuadorian women earned a salary equal or inferior to the NMW wage, these proportions were 7 and 8% in men, respectively. Monthly earnings below the NMW increased the odds of psychological distress in women by more than twofold but not in men, as described by Smith et al. [3] in recently arrived migrants.

Higher educational level has traditionally been associated with better mental and physical health [24, 28, 29] as it is closely related to the socio-economic status and better abilities and resources to cope with stressful events. The interaction found in this study between nationality and educational level in women is revealing: higher education was associated with lower prevalence of PPC in Spaniards, similar to the effect reported by Matud et al. [24], the opposite was observed in Ecuadorians. This may be due to the feeling of frustration and despair on the part of educated Ecuadorian women who do not have access to the jobs for which they were trained. An association between downward social mobility in subjective social status and major depressive episodes among Latino and Asian-American immigrants to the United States has recently been described [30].

The proportion of Ecuadorians who reported they were currently working was considerably higher than that of Spaniards, as was the proportion of Ecuadorians reporting short-term contracts or no employment contracts. Ecuadorian women were, once more, the group with the highest work instability. Not surprisingly, they were the ones reporting the highest dissatisfaction and poorest atmosphere at work. Both job dissatisfaction and poor work atmosphere behaved as risk factors for poor mental health in women and men, as described by others [31].

Social, emotional and economic support was lower in Ecuadorians compared to Spaniards, and even lower in Ecuadorian women compared to men. However, the association between the lack of any form of support and the prevalence of poor mental health varied by sex, nationality and socio-economic position, as has been described by the others [32]. For Spanish women, lack of a confidant was a risk factor for poor mental health, but this effect was not observed in Ecuadorian women. Lack of social support is an established risk factor for poor mental health [25, 33]. For both Spanish and Ecuadorian men, expressing social support and having friends showed beneficial associations with mental health of borderline statistical significance. For Spanish men, lack of partner support was predictive of poor mental health. What was common for everyone was the positive role of economic support. We find this result particularly interesting as having someone who could lend you money in case of need seems to behave as a more universal indicator of support. One could argue that the quality of the emotional and social support economic migrants receive, largely from peers, is different from what Spaniards enjoy, as deprived groups may be in a worse position to support their members.

In attempting to explain the higher rates of depression in women compared to men, various authors have proposed a differential exposure theory by which women are exposed to a higher number of stressors [11]. The multiple roles women are expected to fulfil are proposed as the sources of stress and frustration [11]. This framework would also explain why Ecuadorian women have poorer mental health than both Spanish women and Ecuadorian men, as they are disproportionably exposed to well known stressors in all spheres of their lives. It is to be noted that Ecuadorians are also exposed to other stressors, largely ethnic discrimination, as shown in the findings published by Bhui et al. [7]. Ethnic discrimination was not considered in the present analyses, but has been the subject of a previous paper by our group [6]. It is becoming increasingly clear that, in order to understand gender differences in mental health, it is necessary to take into account both economic situation and nationality [1, 2, 4, 34, 35].

Response rates in some areas of Madrid were low, leading to a selection bias the direction of which is unpredictable. However, excluding data from Madrid did not alter our results. As we discussed in a previous methodological paper, although the proportion of invalid addresses was higher in Ecuadorians because of their higher mobility, response rates were higher in Ecuadorians than in Spaniards. We attribute this to the more cooperative nature of the Ecuadorians, possibly influenced by the official and academic nature of the institutions. Also, the choice of the token, a phone card, may have been more appealing than the petrol voucher [19]. Although the selection of the population in this survey was probabilistic, to be eligible, one had to be registered in the municipal registry. Legal residence is not a prerequisite for registration, but it is possible that we may have under represented the most deprived section of Ecuadorian migration, those with higher mobility and recent migration histories. Information bias could also play a role as cultural differences are likely to affect Ecuadorian’s responses. We believe we have minimized this bias by a careful design of the questionnaire and by ensuring that interviewers visiting Ecuadorians were from Latin America. Most interviewers were women, and this may have introduced a gender bias in the reporting of risk factors and symptoms of mental health disorders. While women may have felt more at ease, men may have felt uncomfortable reporting poor indicators of social success for a “man”. In fact, we worry that this may have led to a certain underestimation of the prevalence of poor mental health in Ecuadorian men. Also, some authors have developed the concept of “frustrated status” to explain why some migrants express fewer symptoms of poor mental health than nationals. The authors attribute this to a complex and multifactorial scenario whereby migrant’s expectations about what can be considered as success have somehow been lowered [36]. However, a recent paper by Schrier et al. suggests that the profile of depressive symptoms was similar in Turkish and Moroccan labour migrants as compared to the native Dutch [37]. Regarding generalizability, the inferences that can be made from this study are applicable to the 33 study areas, which are situated in the regions with the highest number of Ecuadorian migrants in Spain. Finally, we are aware that the statistical power and the precision of some of the estimates are low.

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study on the mental health of Ecuadorian female and male economic migrants in an industrialized country. It should be noted that we measured mental health by the GHQ-28, which is used for screening purposes rather than for clinical diagnosis. Our findings have implications for future research, policy development and service provision. The 2008–2011 strategic plan for equal opportunities developed by the Ministry of Equal Rights in Spain [38] identifies migrant women as a group with special needs, different from those of Spanish women and migrant men. Our study identifies the need for positive actions aimed at migrant women in the employment and economic sphere, as well as the family environment. We hope our findings will help convert the recommendations of the plan into specific interventions.

References

Bhugra D (2004) Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109:243–258

Taloyan M, Johansson SE, Sundquist J, Kocturk TO, Johansson LM (2008) Psychological distress among Kurdish immigrants in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 36:190–196

Smith KL, Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Glazier RH (2007) Gender, income and immigration differences in depression in Canadian urban centres. Can J Public Health 98:149–153

Takeuchi DT, Alegria M, Jackson JS, Williams DR (2007) Immigration and mental health: diverse findings in Asian, black, and Latino populations. Am J Public Health 97:11–12

Dalgard OS, Thapa SB (2007) Immigration, social integration and mental health in Norway, with focus on gender differences. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 3:24

Llácer A, del Amo J, García-Fulgueira A, Ibáñez-Rojo V, García-Pino R, Jarrín I et al (2009) Discrimination and mental health in Ecuadorian immigrants in Spain. J Epidemiol Community Health 63:766–772

Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, Weich S (2005) Racial/ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: findings from the EMPIRIC study of ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health 95:496–501

The world health report 2001—Mental health: new understanding, new hope. WHO. Available in: http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/index.html

Weich S, Sloggett A, Lewis G (1998) Social roles and gender difference in the prevalence of common mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 173:489–493

Nazroo J, Edwards A, Brown G (1998) Gender differences in the prevalence of depression: artefact, alternative disorders, biology or roles? Sociol Health Illn 20:312–330

Elliott M (2001) Gender differences in causes of depression. Women Health 33:163–177

MacLean H, Glynn K, Ansara D (2004) Multiple roles and women’s mental health in Canada. BMC Womens Health 4(Suppl 1):S3

Turner RJ, Avison WR (2003) Status variations in stress exposure: implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. J Health Soc Behav 44:488–505

Carta MG, Reda MA, Consul ME, Brasesco V, Cetkovich-Bakmans M, Hardoy MC (2006) Depressive episodes in Sardinian emigrants to Argentina: why are females at risk? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41:452–456

Meadows LM, Thurston WE, Melton C (2001) Immigrant women’s health. Soc Sci Med 52:1451–1458

Thapa SB, Hauff E (2005) Gender differences in factors associated with psychological distress among immigrants from low- and middle-income countries—findings from the Oslo Health Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:78–84

De Wit MA, Tuinebreijer WC, Dekker J, Beekman AJ, Gorissen WH, Schrier AC et al (2008) Depressive and anxiety disorders in different ethnic groups: a population based study among native Dutch, and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese migrants in Amsterdam. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43:905–912

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE). Available in: http://www.ine.es

Álvarez-del Arco D, Llácer A, del Amo J, García-Fulgueiras A, García-Pina R, García-Ortuzar V et al (2009) Methodology and field work logistics of a multilevel research study on the influence if neighbourhoods’ characteristics on natives and Ecuadorians’ mental health in Spain. Rev Esp Salud Pública 8:493–508

Goldberg DP, Hillier VF (1979) A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 9:139–145

Lobo A, Perez-Echeverria MJ, Artal J (1986) Validity of the scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) in a Spanish population. Psychol Med 16:135–140

Broadhead W, Gehlbach S, de Gruy F, Kaplan BH (1988) The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care 26:709–723

Bellón Saameño JA, Delgado Sánchez A, Luna del Castillo JD, Lardelli Claret P (1996) Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de apoyo Social funcional Duke-INC-11. Atención primaria 18(4):153–163

Matud MP, Guerrero K, Matías RG (2006) Relevance of socio-demographic variables in gender differences in depression. Int J Clin Health Psychol 6:7–21

Siefert K, Finlayson TL, Williams DR, Delva J, Ismail AI (2007) Modifiable risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in low-income African American mothers. Am J Orthopsychiatry 77:113–123

Crosier T, Butterworth P, Rodgers B (2007) Mental health problems among single and partnered mothers. The role of financial hardship and social support. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42:6–13

Brown GW, Moran PM (1997) Single mothers, poverty and depression. Psychol Med 27:21–33

Myers HF, Lesser I, Rodriguez N, Mira CB, Hwang WC, Camp C et al (2002) Ethnic differences in clinical presentation of depression in adult women. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 8:138–156

Alvarado BE, Zunzunegui MV, Beland F, Sicotte M, Tellechea L (2007) Social and gender inequalities in depressive symptoms among urban older adults of Latin America and the Caribbean. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 62:S226–S236

Nicklett EJ, Burgard SA (2009) Downward social mobility and major depressive episodes among Latino and Asian-American immigrants to the United States. Am J Epidemiol 170:793–801

Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL (2005) The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 62:105–112

Cuellar I, Bastida E, Braccio SM (2004) Residency in the United States, subjective well-being, and depression in an older Mexican-origin sample. J Aging Health 16:447–466

Israel BA, Farquhar SA, Schulz AJ, James SA, Parker EA (2002) The relationship between social support, stress, and health among women on Detroit’s East Side. Health Educ Behav 29:342–360

Bromberger JT, Harlow S, Avis N, Kravitz HM, Cordal A (2004) Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged women: the study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Am J Public Health 94:1378–1385

Almeida-Filho N, Lessa I, Magalhaes L, Araujo MJ, Aquino E, James SA et al (2004) Social inequality and depressive disorders in Bahia, Brazil: interactions of gender, ethnicity, and social class. Soc Sci Med 59:1339–1353

Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Anderson K (2004) Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:1226–1233

Fassaert T, de Wit MA, Tuinebreijer WC, Verhoeff AP, Beekman AT, Dekker J (2009) Perceived need for mental health care among non-western labour migrants. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44:208–216

Ministerio de Igualdad. Plan Estratégico de Igualdad de Oportunidades (2008–2011). Available in: http://www.migualdad.es/igualdad/PlanEstrategico.pdf

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the Spanish Research Fund (FIS PI041026). Débora Álvarez was employed by CIBERESP (Ciber of Epidemiology and Public Health). Inma Jarrín is employed with funds from RIS (Spanish HIV Research Network for excellence), RD06/006.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Del Amo, J., Jarrín, I., García-Fulgueiras, A. et al. Mental health in Ecuadorian migrants from a population-based survey: the importance of social determinants and gender roles. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46, 1143–1152 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0288-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0288-x