Abstract

Background

Past research on stigmatization of the mentally ill has emphasized the importance of beliefs about mental illness in determining preferred social distance to those with such illnesses. In the current paper we examine the importance of perceived social norms in improving the prediction of social distance preferences.

Methods

Two hundred university students completed scales measuring their beliefs about either depression or schizophrenia; their perception of relevant social norms and their preferred level of social distance to someone with schizophrenia or depression. Measures of social desirability bias were also completed.

Results

The proportion of variance in preferred social distance was approximately doubled when perceived norms were added to beliefs about illness in a regression equation. Perceived norms were the most important predictor of social distance to an individual with either illness. A general preference for social distance towards a control, non-ill person was also an independent predictor of behavioral intentions toward someone with either schizophrenia or depression.

Conclusions

Perceived social norms are an important contributor to an individual’s social distance to those with mental illness. Messages designed to influence perceived social norms may help reduce stigmatization of the mentally ill.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reducing the stigma of mental illness has been identified as one of the major challenges of the mental health field [38, 64, 74]. Negative reactions to those with mental illness are thought to contribute to delays in help seeking [8, 21] as well as placing many individuals who have received psychiatric treatment at disadvantages in such areas as employment, income, housing, personal relationships and health care [50, 51, 54, 76, 77]. Aspects of this stigma can also be internalized by those with mental illness with implications for their psychological well-being and self-esteem [20, 48, 62, 79].

In general, approaches to understanding this stigmatization have emphasized the importance of beliefs about the mentally ill [5, 18, 19, 47, 75]. It is suggested that prominent stereotyped beliefs about mental illness include that those with mental illness are (1) dangerous; (2) have contributed to their own misfortune through character weakness; (3) are socially unpredictable and inappropriate; (4) are unlikely to greatly improve with treatment; with the only potentially positive aspect of the stereotype of mental illness being belief that it may be associated with artistic talent or genius [5, 27, 36]. There is particularly strong evidence of significant relationships between wishing to maintain greater social distance towards those with mental illness and beliefs about their dangerousness [3, 5, 46, 75] responsibility for their own illness [52] and the unpredictability or inappropriateness of their social behavior [5, 69].

Angermeyer and Matschinger [5] assessed the relative importance of beliefs about schizophrenia in predicting behavioral intentions that reflect social distance. Using data from a representative sample of over 5,000 from the population of Germany, they found that beliefs about social inappropriateness or unpredictability and dangerousness were the most important predictors of behavioural intentions towards those with schizophrenia. However, the total amount of variance in social distance accounted for by beliefs about schizophrenia and demographic characteristics of respondents was limited to 27%.

Many interventions have been implemented with the intention of improving reactions to the mentally ill by changing beliefs about the nature of mental illness. Unfortunately, there is often no evaluation of their effectiveness. Those few interventions that have been evaluated have often succeeded in changing stated beliefs and attitudes, but have yielded much less evidence of improvement in behavioural intentions toward those with mental illness, [29, 56, 57, 60, 67]. Reviews of the relevant literature have also concluded that any effects of efforts to reduce the stigma of mental illness have largely been restricted to changes in verbally expressed beliefs and attitudes rather than behavioural intentions or behaviour [63, 70, 77]. In addition, there is evidence that desirable changes over time in the public beliefs about mental illness are not necessarily accompanied by significant improvement in behavioural intentions [6].

The above findings are consistent with suggestions in the more general literature on prejudice and stigma that stereotyped beliefs may have been overemphasized as determinants of behavioral intentions or actual behavior [39, 55]. Goffman’s seminal writings on stigma emphasized the importance of a perceived social consensus or norms concerning behavioral responses to stigmatized individuals [31, 43] and there have been several recent calls for more attention to the social normative context of stigmatization in general and stigmatization of mental illness in particular [33, 37, 80]. As Link et al. [48] have noted, “People form expectations as to whether most people will reject an individual with mental illness as a friend, employee, neighbour or intimate partner…” (p 203). It has been demonstrated in other contexts that an individual’s perception of social norms can have an influence on his or her preferred social distance with reference to stigmatized groups independently of personal beliefs about that group [22, 37, 73], but this has not been investigated in the context of mental illness.

The purpose of the current investigation was to examine the relative importance of perceived social norms and beliefs about mental illness as predictors of preferred social distance towards the mentally ill. If perceived social norms are an independent predictor of preferred social distance to those with mental illness, it could have significant implications for the design of interventions to change such reactions [15, 68]. The specific hypothesis tested was that perceived social norms make a significant contribution to behavioural intentions with respect to individuals with schizophrenia or depression independently of beliefs about such illnesses.

Method

Participants

Participants were 200 undergraduate students at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada who responded to advertisements to participate in the study. Participants were offered $15 as compensation for their time. All participants signed an informed consent and the study protocol was approved by the relevant Ethics Board at the University. There were 90 men and 110 women in the sample, with mean age of 21.5 years (SD = 5.0 years).

Measures

Mental illness vignettes

Many studies of reactions to those with mental illness have asked about reaction to an unspecified “mental illness”, but such a term is rather amorphous and likely to give rise to varying referents for different respondents [49, 59]. An alternative strategy to avoid this ambiguity has been the use of vignettes, which allow assessment of determinants of participant’s reaction to a specific presentation of mental illness. For current purposes we used two vignettes, one concerning an individual with schizophrenia and one concerning an individual with depression. These vignettes had been prepared by Angermeyer and colleagues for their extensive population survey in Germany concerning reactions to mental illness, [4–6]. Each vignette concerned a hypothetical acquaintance “AB” and was developed to reflect symptoms in the DSM criteria for schizophrenia or depression as established by five experts in psychopathology. Aside from very minor wording changes to improve readability of the vignettes in English, the only substantial modifications of the vignettes were that the gender of the person described was varied so that in approximately half the cases the person was described as male and in the other half as female, and a final sentence was added providing a diagnosis so that subjects were responding to a combination of symptoms and diagnoses. Each subject received only one vignette describing mental illness (either schizophrenia or depression).

Because preferred social distance toward an individual with a mental illness may at least partially reflect general preferences or habits not specific to mental illness, we also had subjects respond to a vignette describing a control, not ill individual (CD). The responses this vignette were always completed before the vignette describing depression or schizophrenia. The vignettes describing schizophrenia, depression and the control comparison are in Appendix I.

Behavioural intentions

Behavioural intentions towards the person described in the vignette were assessed using slightly modified versions of six items adapted by Link et al. [45] from the Bogardus Social Distance Scale [11]. These included items in which respondents indicated on a five point scale (from “I certainly would” to “I certainly would not”) the likelihood that they would engage in a series of hypothetical situations which involved: taking a job where they would be working with the individual; moving into a home next door to the individual; becoming a friend of the individual; renting a room to the individual; recommending the person for a job; and supporting marriage to their sibling or child. These items were completed by participants with response to the person in the control vignette and either the individual with schizophrenia or depression. Responses were averaged across items to provide a cumulative index with higher scores indicating greater social distance. Coefficient alpha for the social distance scale was 0.84.

Beliefs about illness

A set of items was included to assess the five dimensions of beliefs about illness identified by Angermeyer and Matschinger [5] and Hayward and Bright [36]. Given evidence that empathetic behaviour towards another person can be influenced by perceived similarity [9, 10] we also included items designed to assess the extent to which the symptoms of illness are believed to vary on a continuum of similarity with everyday experience. Ten of the items used were adapted from Angermeyer and Matschinger [5] and another ten developed by the authors. Respondents rated each item on a five-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Corresponding to the nature of the illness vignette presented to each subject, ratings were made with respect to personal beliefs about either schizophrenia or depression.

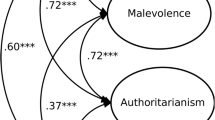

Results of a factor analysis using principal axis factoring and promax rotation are presented in Table 1. Promax rotation was used as it was anticipated the factors could be correlated. Consistent with expectations a scree plot suggested a six-factor solution and the resulting item loadings suggest the anticipated dimensions of attribution of personal responsibility; belief in continuity between everyday experience and illness; danger; social inappropriateness; perception of talent and ineffectiveness of treatment. Similar factor structures emerge if the factor analysis is carried out separately for each diagnosis. Scores on each of the six dimensions were computed using the average score for each of the relevant items with higher scores indicating more negative beliefs (greater personal responsibility, less continuity with normal experience, greater danger, more socially inappropriate behavior; less talent/intelligence and poor treatment outcome). The coefficient alphas for the first four scales were respectable (0.74–0.83). The talent/intelligence and treatment outcome scales, however, showed an alpha of 0.57 and 0.48, respectively. Angermeyer and Matschinger [5] also found lower internal consistency for these scales than danger, attribution of responsibility or social inappropriateness. An assessment of the two-week test retest reliability of each of the scales was carried out using 20 respondents and all yielded reliability of at least 0.75.

Perceived norms

There is evidence that it may be important to assess two types of perceived social norms: injunctive norms, which reflect perceptions of what most others would approve of, and descriptive norms, which reflect what others would actually do [13, 16, 40, 72]. Following precedents [13, 78], perceived injunctive norms were assessed by a seven point scale rating the extent with which people who are important to the respondent would approve of each specific behaviour. For instance, participants responded to the item “If you recommended AB for a job, people who are important to you, such as family and friends, would:” using a seven-point scale varying between “Very strongly approve” to “Very strongly disapprove.” For descriptive norms, respondents indicated how likely it was that those people would actually engage in the behaviour. As an example, they responded to the item “How likely is it that people who are important to you, such as family and friends, would themselves actually recommend AB for a job, if they were in your position,” using a seven-point scale anchored by “They certainly would” and “They certainly would not.” In order to obtain an aggregate assessment of perceived norms with respect to all six specific behaviours, we calculated a cumulative score based on all items assessing either descriptive or injunctive normative beliefs. These included norms with respect to working with, moving next door, becoming a friend, renting a room, recommending for a job, and supporting marriage to a family member; with a higher score indicating a belief that others would favour more social distance. The coefficient alpha of this scale was 0.89.

Social desirability

Concern has been expressed that responses to questions about mental illness may be influenced by a bias to present a socially desirable impression [2, 33–35]. In order to examine this possibility we included the Crowne-Marlowe Social Desirability Scale [24]. This 33-item scale is designed to provide an index of a respondent’s tendency to present a socially desirable impression through endorsing as true self-descriptions that are acceptable but improbable, or denying descriptions that are undesirable but probable. Sample items include endorsement of “I never hesitate to go out of my way to help someone in trouble” and denial of “I sometimes feel resentful when I don’t get my own way.” The alpha coefficient of this cumulative index in the current sample was 0.89.

Results

Effects of gender and target illness

A three-way analysis of variance was carried out to examine any effects of gender of respondent, gender of the person in the scenario and the nature of the illness described on the beliefs about illness or perceived norms. The gender of the person in the scenario had no effect on any of the measures. However, gender of the participants did make a difference. Men attributed a significantly higher personal responsibility for either illness (F = 6.88, df = 1.192, P < 0.01), and perceived normative expectations as less favorable to social contact with the vignette concerning a mentally ill person (F = 4.11, df = 1.192, P < 0.05). There were no other significant main or interaction effects for gender of the respondent.

There were several significant main effects for the type of illness described. In comparison to depression, schizophrenia was associated with a preference for greater social distance (\( \bar {x} = 3.8 \), SD = 0.73 versus 3.4 SD = 0.81 for schizophrenia and depression, respectively; F = 8.74, df = 1.192, P < 0.01); greater belief in danger (\( \bar {x} = 2.4 \), SD = 0.70 versus \( \bar {x} = 2.1 \), SD = 0.77; F = 6.05, df = 1.192, P < 0.05); greater expectation of socially inappropriate behavior (\( \bar {x} = 3.5 \), SD = 0.72 versus \( \bar {x} = 2.9 \), SD = 0.82; F = 25.2, df = 1.192, P < 0.001); less belief in personal responsibility for illness (\( \bar {x} = 2.3 \); SD = 0.88 versus \( \bar {x} = 2.9 \), SD = 0.83; F = 28.67, df = 1.192, P < .001); and less perceived continuity with normal experience (\( \bar {x} = 3.4 \), SD = 0.86 versus \( \bar {x} = 0.44 \); SD = 0.54; F = 85.98, df = 1,192, P < 0.001). There were no significant interactions of target illness with either gender of the person in the vignette or gender of the respondent.

Social desirability

There were no significant correlations between the responses to the social desirability scale and current measures of belief, perceived norms or social distance.

Relationship between personal beliefs and perceived norms

Table 2 presents the Pearson bivariate correlations between each of the measures of personal beliefs and perceived norms. There were some correlations between belief scales. In particular, belief in danger was positively correlated with expectations of socially inappropriate behaviour and belief in greater personal responsibility for illness. Also, greater belief in discontinuity between illness and normal behaviour was associated with less belief in personal responsibility and greater expectation of socially inappropriate behaviour. Beliefs about illness are also associated with perceived norms. Perceived norms favouring greater social distance were positively correlated with belief in danger, social inappropriateness, personal responsibility and lower talent or intelligence.

Prediction of Social distance

Table 3 presents the correlations of each of the measures of belief, perceived norms and preferred social distance to a normal person with preferred social distance to the vignette featuring schizophrenia or depression. Concerns about danger and inappropriate social behaviour were significantly related to a preference for greater social distance to the vignette concerning either form of illness, with belief in personal responsibility also being correlated with social distance to the person with schizophrenia. It is also apparent that social distance to an ill person is correlated with social distance to the person in the control vignette suggesting there is some common variance reflecting a general preference for social distance. With respect to social distance toward the vignettes concerning an individual with schizophrenia or depression, the largest correlations were with perceived normative expectations about behaviour. In both cases the greater the belief that others important to the respondent would disapprove of and not engage in contact with the ill person, the greater the personally preferred social distance.

Multiple regression analyses were carried out to assess the independence and relative importance of predictors of preferred social distance to the vignettes describing either schizophrenia or depression. The significant correlates of social distance in Table 3 were all entered into regression analyses for the prediction of social distance separately for schizophrenia and depression, using the SPSS “enter” option. In order to attain statistical significance as a predictor of social distance in such an equation, a variable must predict variance in outcome independently of other predictors [71]. The results are presented in Table 4. There was no evidence of significant multicollinearity between predictors with the relevant SPSS tolerance statistics varying between 0.63 and 0.94 [71]. With respect to social distance toward the person in the schizophrenia or depression vignette, belief that the illness is associated with socially inappropriate and embarrassing behaviour, preferred social distance to the control person and perceived social norm were each independent predictors. For schizophrenia, belief in danger being associated with the illness was at borderline significance as an independent predictor of greater social distance.

Subsequent stepwise regression analyses were carried out to assess the relative importance of each predictor in adding incrementally to the prediction of social distance. In the case of schizophrenia, the order of entry was perceived norms as the single most important predictor with only belief about social inappropriateness predicting additional variance. For depression, perceived norms was the first entry into the prediction equation followed by preferred distance to the normal target with none of the other predictors adding significantly to the variance accounted for in social distance.

Discussion

A central focus of theory and research about the stigmatization of mental illness has been on the importance of negative stereotypical beliefs [5, 18, 36]. Our findings support previous reports showing that beliefs concerning inappropriateness or disruptiveness of social behaviour by those with mental illness and their potential dangerousness are the stereotype dimensions that show the greatest relationship to preferred social distance [5, 52, 75]. Such findings are also consistent with models of stigmatization that emphasize the survival functions of avoiding groups who are seen as dangerous or with whom interaction is seen as more costly than beneficial [42].

Our data also reinforce previous reports that there is only a modest proportion of variance in social distance that can be accounted for by the beliefs associated with the stereotype of mental illness. For instance, with respect to schizophrenia, Angermeyer & Matschinger, in their population survey in Germany, found that beliefs about danger, social disruptiveness, responsibility and prognosis when combined with demographic factors accounted for about 27% of the variance in preferred social distance. Similarly, in a population survey in the Netherlands, van’tVeer et al. [75] found that demographics and beliefs about mental illness accounted for 20% of variance in preferred social distance. In our data, measures of stereotypical beliefs about schizophrenia plus gender accounted for 28% of such variance. The differences that we found in the beliefs about and social distance to depression and schizophrenia also parallel reports from America, Australia, Britain, Germany and Japan [4, 23, 33, 58].

The modest relation between reported beliefs about mental illness and behavioural social distance is consistent with research in other areas suggesting that personal beliefs and attitudes about groups are not always strongly related to behavioural discrimination [25, 28] and that such beliefs may have been overemphasized as determinants of negative behavioural reactions to stigmatized groups [37, 39, 55]. As noted earlier, there is also evidence that interventions that change beliefs about the nature of mental illness often have little impact on behavioural intentions [56, 57, 60, 61, 67].

Stigma as a construct emphasizes the existence of a shared social consensus or expectation that members of the stigmatized category are to be avoided or marginalized in social interaction [26, 31, 42, 44]. Social behaviours with respect to the target group or person are not only influenced by the beliefs and attitudes of an individual, but also the individual’s perception of the expectations of others about how one should behave [1, 16, 73]. There is now evidence that perceived norms, as measured in this study, are independent predictors of many forms of social behaviour [7, 40, 41, 78], including responses to groups who are stigmatized or subject to discrimination [22, 30, 37, 68].

The current report is the first, of which we are aware, to examine the importance of perceived norms as an independent influence on behavioural intentions to those with mental illness specifically. We found that perceived norms made an independent contribution to the prediction of social distance beyond that attributable to beliefs about mental illness. In the case of the schizophrenia vignette, personal beliefs about the nature of the illness accounted for 29% of the variance in preferred social distance. This increased to 51% with the addition of perceived social norms. For depression, illness beliefs accounted for 13% of the variance in preferred social distance, and this increased to 34% with the addition of perceived norms. In addition, perception of norms was the most powerful single predictor of social distance, as indicated by behavioral intentions, with respect to both schizophrenia and depression. Uncertainty in personal beliefs about a person or concept has been found to increase the influence of perceived norms in determining behavioral intentions and behavior [14, 16]. Issues related to mental illness and the behavior of those with such illness are sometimes contentious even among experts and can involve subtle concepts. Although the issue of certainty of beliefs related to the stigmatization of the mentally ill has not been extensively investigated, it would be interesting in future to test the prediction that the influence of perceived norms will be greater as confidence in personal beliefs about illness is lower.

There were two other noteworthy findings in the current study. The first is that a measure of bias towards responding in a socially desirable manner did not correlate with any of the measures of beliefs, perceived norms or social distance. The second is that there was a correlation between preferred social distance towards a control vignette featuring a person without illness and the same measure with respect to a vignette concerning schizophrenia or depression. This issue has been largely ignored in previous research on social distance towards the mentally ill, which has often implicitly assumed that such behavioral intentions are solely determined by personal dispositions focused specifically on mental illness. The current findings suggest that behavioural responses to those with mental illness may partially reflect more general preferences concerning social interaction with anyone. Such dispositions are likely related to relatively broad traits such as extraversion, social anxiety or shyness within cultures and likely to vary considerably between cultures.

One limitation of the current study is the use of a paper and pencil measure of social distance. This is a common measure in research on the stigmatization of those with mental illness [49] and such measures of behavioral intention can predict significant variation in actual behavior [7]. Nevertheless, it will be important in future to more fully assess the importance of beliefs about mental illness and perceived norms in predicting overt behavior. From some perspectives, the use of university students as respondents is also a limitation. While the responses of such students are of interest and importance in their own right, one could question whether findings based on such a sample will generalize to a wider population. In addition, our recruitment procedure may have attracted students with a particular interest in mental health issues or introduced other biases. As noted earlier, our findings regarding the importance of specific dimensions of belief about mental illness and the total variance in social distance that they account for is very similar to that from previously published general population surveys. We intend, however, in future to assess the generalizability of our findings regarding the importance of perceived norms in non-student samples.

The finding that perceived social norms are important predictors of social distance towards those with mental illness could have implications for the design of more effective interventions to reduce the marginalization of the mentally ill. In recent years, there have been evaluations of the impact of interventions designed to modify people’s perception of normative behaviour or expectations, or increase the salience of norms that are supportive of a target response. Such interventions generally provided feedback to individuals concerning how their behavior compares to their reference group or provided models of desired behavior in an effort to change perceived norms [12, 15, 17, 22, 32, 53, 65, 68]. These methods have generally been found effective in bringing about changes in behaviour, and a recent report suggests that messages conveying likely social approval (related to injunctive norms) may have even more reliable impacts on behaviour.[66] Although the design of effective “normative messages” requires subtlety [15], there is now evidence of such interventions being successful in bringing about behaviour change in such contexts as recycling [15, 65], littering [12], energy conservation [17], and inter-racial behaviour [22, 68]. Efforts to creatively apply such normative approaches to reducing the stigma of mental illness certainly seem warranted.

References

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Alexander LA, Link BG (2003) The impact of contact on stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness. J Ment Health 12:271–289

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (1997) Social distance towards the mentally ill: results of representative surveys in the Federal Republic of Germany. Psychol Med 27:131–141

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (2003) Public beliefs about schizophrenia and depression: similarities and differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epid 38:526–534

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (2004) The stereotype of schizophrenia and its impact on discrimination against people with schizophrenia: results of a representative survey in Germany. Schizophr Bull 30:1049–1061

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (2005) Causal beliefs and attitudes to people with schizophrenia. Trend analysis based on data from two population surveys in Germany. Br J Psychiatry 186:331–334

Armitage CJ, Conner M (2001) Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 40:471–499

Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF, Christensen H (2006) Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 40:51–54

Batson CD, Sager K, Garst E, Kang M, Rubchinsky K, Dawson K (1997) Is empathy due to self-other merging? J Pers Soc Psychol 73:495–509

Batson CD, Lishner DA, Cook J, Sawyer S (2005) Similarity and nurturance: two possible sources of empathy for strangers. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 27:15–25

Bogardus ES (1925) Social distance and its origins. J Appl Sociol 9:216–226

Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA (1990) A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J Pers Soc Psychol 58:1015–1026

Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA, Reno RR (1991) A focus theory of normative conduct: a theoretical refinement and re-evaluation of the roles of norms in human behavior. In: Zanna MP (ed) Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press, New York, pp 201–234

Cialdini RB (2001) Influence, science and practice, 4th edn. Allyn & Bacon, Boston

Cialdini RB (2003) Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 12:105–109

Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ (2004) Social influence: compliance and conformity. Annu Rev Sociol 55:591–621

Cialdini RB (2005) Basic social influences is underestimated. Psychol Inq 16:158–161

Corrigan PW (2000) Mental health stigma as social attribution: implications for research methods and attitude change. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 7:48–67

Corrigan PW (2002) Testing social cognitive models of mental illness stigma: the prairie state stigma studies. Psychiatr Rehabil Skills 6:232–254

Corrigan PW, Watson AC (2002) The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 9:35–53

Corrigan PW (2004) How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol 59:614–625

Crandall CS, Eshleman A, O’Brien L (2002) Social norms and the expression and suppression of prejudice: the struggle for internalization. J Pers Soc Psychol 82:359–378

Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ (2000) Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br J Psychiatry 177:4–7

Crowne DP, Marlowe D (1960) A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J Consult Psychol 24:349–354

Dovidio JF, Brigham JC, Johnson BT, Gaertner SL (1996) Stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination: another look. In: Macrae N, Stangor C, Hewstone M (eds) Stereotypes and stereotyping. Guildford, New York, pp 276–319

Dovidio JF, Major B, Crocker J (2000) Stigma: introduction and overview. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck Re, Hebl MR, Hull JG (eds) Social psychological perspectives. Guilford, New York, pp 1–28

Estroff SE, Penn DL, Toporek JR (2004) From stigma to discrimination: an analysis of community efforts to reduce the negative consequences of having a psychiatric disorder and label. Schizophr Bull 30:493–509

Fiske ST (1998) Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G (eds) The handbook of social psychology. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 357–414

Gaebel W, Baumann AE (2003) Interventions to reduce the stigma associated with severe mental illness: experiences from the open the doors program in Germany. Can J Psychiatry 48:657–662

Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF (1986) The aversive form of racism. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL (eds) Prejudice, discrimination and racism. Academic Press, Orlando

Goffman E (1963) Stigma: notes on the management of spoilt identity. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Goldstein NJ, Cialdini RB (2007) Using social norms as a lever of social influence. In: Pratkanis AR (ed) The science of social influence: advances and future progress. Psychology Press, New York, pp 167–191

Griffiths KM, Nakane Y, Christensen H, Yoshioka K, Jorm AF, Nakane H (2006) Stigma in response to mental disorders: a comparison of Australia and Japan. BMC Psychiatry 6:21–32

Haghighat R (2001) A unitary theory of stigmatisation: pursuit of self-interest and routes to destigmatisation. Br J Psychiatry 178:207–215

Haghighat R (2005) The development of an instrument to measure stigmatization: factor analysis and origin of stigmatization. Eur J Psychiatry 19:144–154

Hayward P, Bright JA (1997) Stigma and mental illness: a review and critique. J Ment Health 6:345–354

Hebl MR, Dovidio JF (2005) Promoting the “social” in the examination of social stigmas. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 9:156–182

Hinshaw SP, Cicchetti D (2000) Stigma and mental disorder: conceptions of illness, public attitudes, personal disclosure, and social policy. Dev Psychopathol 12:555–598

Jussim L, Nelson TE, Manis M, Soffin S (1995) Prejudice, stereotypes, and labeling effects: Sources of bias in person perception. J Pers Soc Psychol 68:228–246

Kallgren AA, Reno RR, Cialdini RB (2000) A focus theory of normative conduct: when norms do and do not affect behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 26:1002–1012

Kashima Y, Gallois C, McCamish M (1993) The theory of reasoned action and cooperative behaviour: it takes two to use a condom. Br J Soc Psychol 32:227–239

Kurzban R, Leary MR (2001) Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: the functions of social exclusion. Psychol Bull 127:187–208

Kusow AM (2004) Contesting stigma: on Goffman’s assumption of normative order. Symbolic Interpretation 27:179–197

Leary MR, Schreindorfer LS (1998) The stigmatization of HIV and AIDS: rubbing salt in the wound. In: Derlega V, Barbee A (eds) HIV infection and social interaction. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 12–29

Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF (1987) The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. Am J Sociol 92:1461–1500

Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA (1999) Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health 89:1328–1333

Link BG, Phelan JC (2001) Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 27:363–385

Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC (2002) On describing and seeking to change the experience of stigma. Psychiatr Rehabil Skills 6:201–231

Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY (2004) Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull 30:511–541

Lloyd C, Sullivan D, Williams PL (2005) Perceptions of social stigma and its effect on interpersonal relationships of young males who experience a psychotic disorder. Aust Occup Ther J 52:243–250

Manning C, White PD (1995) Attitudes of employers to the mentally ill. Psychiatr Bull 19:541–543

Martin J, Pescosolido BA, Tuck SA (2000) Of fear and loathing: the role of disturbing behavior, labels, and causal attributions in shaping public attitudes toward people with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav 41:208–223

Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA (2004) Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol 72:434–447

Page S (1995) Effects of the mental illness label in 1993: acceptance and rejection in the community. J Health Soc Policy 7:61–68

Park B, Judd CM (2005) Rethinking the link between categorization and prejudice within the social cognition perspective. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 9:108–130

Paykel ES, Hart D, Priest RG (1998) Changes in public attitudes to depression during the defeat depression campaign. Br J Psychiatry 173:519–522

Penn DL, Link BG (2002) Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia. III. The role of target gender, laboratory-induced contact, and factual information. Psychiatr Rehabil Skills 6:255–270

Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, Stueve A, Kikuzawa S (1999) The public’s view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. Am J Public Health 89:1339–1345

Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA (2000) Public conceptions of mental illness in 1950 and 1996: what is mental illness and is it to be feared? J Health Soc Behav 41:188–208

Pinfold V, Huxley P, Thornicroft G, Farmer P, Toulmin H, Graham T (2003) Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination–evaluating an educational intervention with the police force in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38:337–344

Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P, Graham T (2003) Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry 182:342–346

Pyne JM, Kuc EJ, Schroeder PJ, Fortney JC, Edlund M, Sullivan G (2004) Relationship between perceived stigma and depression severity. J Nerv Ment Dis 192:278–283

Rosen A, Walter G, Casey D, Hocking B (2000) Combating psychiatric stigma: an overview of contemporary initiatives. Aust Psychiatry 8:19–26

Sartorius N (1998) Stigma: what can psychiatrists do about it? Lancet 352:1058–1059

Schultz PW (1999) Changing behavior with normative feedback interventions: a field experiment on curbing recycling. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 21:25–36

Schultz PW, Nolan JM, Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ, Griskevicius V (2007) The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol Sci 18:429–434

Schulze B, Richter-Werling M, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2003) Crazy? So what! Effects of a school project on students’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 107:142–150

Sechrist GB, Stangor C (2001) Perceived consensus influences intergroup behavior and stereotype accessibility. J Pers Soc Psychol 80:645–654

Socall DW, Holtgraves T (1992) Attitudes toward the mentally ill: the effects of label and beliefs. Sociol Q 33:435–445

Stuart H (2002) Stigmatisation. Lecons tirees des programmes de reduction. Sante Mentale au Quebec 28:37–53

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2001) Using multivariate statistics. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Terry DJ, Hogg MS (1996) Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: a role for group identification. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 22:776–793

Terry DJ, Hogg MA (2000) Attitudes, behavior, and social context: the role of norms and group membership. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahway

United States Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, Center for Mental Health Services (U.S.), National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.) (1999) Mental health: A report of the Surgeon Genearal. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, Pittsburgh, PA

van’tVeer JTB, Kraan HF, Drosseart SHC, Modde JM (2006) Determinants that shape public attitudes towards the mentally ill: a Dutch public study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41:310–317

Wahl OF (1999) Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull 25:467–478

Warner R (2001) Combating the stigma of schizophrenia. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 10:12–17

White KM, Terry DJ, Hogg MA (1994) Safer sex behavior: the role of attitudes, norms, and control factors. J Appl Soc Psychol 24:2164–2192

Wright ER, Gronfein WP, Owens TJ (2000) Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. J Health Soc Behav 41:68–90

Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B (2007) Culture and stigma: adding moral experience to stigma theory. Soc Sci Med 64:1524–1535

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest: None of the authors have any financial interest or affiliations with any organization whose financial interests might be affected by material in the manuscript or which might potentially bias it. This research was supported by a grant from the Social Sciences And Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Vignette: schizophrenia

Imagine that you know the following about an acquaintance (AB) with whom you occasionally spend your leisure time.

In the past months, your acquaintance AB appears to have changed. More and more, he/she has retreated from his/her friends and colleagues, up to the point of avoiding them. If someone managed to involve him/her in a conversation, he/she would only talk about whether some people have the natural gift of reading other people’s thoughts. This question became his/her sole concern. In contrast with his/her previous habits, he/she has stopped taking care of his/her appearance and looked increasingly untidy. At work, AB seemed absent-minded and frequently made mistakes. As a consequence, he/she has already been summoned to his/her boss.

Finally, AB stayed away from work for an entire week without an excuse. Upon his/her return, he/she seemed anxious and harassed. He/she reports that he/she is now absolutely certain that people cannot only read other people’s thoughts, but that they also directly influence them. He/she was however unsure who would steer his/her thoughts. He/she also said that, when thinking, he/she was continually interrupted. Frequently, he/she would even hear those people talk to him/her, and they would give him/her instructions. Sometimes, they would also talk to each other and make fun of whatever he/she was doing at the time. He/she said that the situation was particularly bad at his/her apartment. At home, he/she would really feel threatened, and would be terribly scared. Hence, he/she had not spent the night at his/her place for the past week, but rather he/she had hidden in hotel rooms and hardly dared to go out. AB has now sought professional help and was told he/she appears to be suffering from schizophrenia.

Vignette: major depressive disorder

Imagine that you know the following about an acquaintance (AB) with whom you occasionally spend your leisure time.

Within the past two months, your acquaintance AB has changed in his/her nature. In contrast to previously, he/she is down and sad without being able to give a concrete reason for his/her feeling low. He/she appears serious and worried. There is no longer anything that will make him/her laugh. He/she hardly ever talks, and if he/she says something, he/she speaks in a low tone of voice about the worries he/she has with regard to his/her future. AB feels useless and has the impression he/she does everything wrong. All attempts to cheer him/her up have failed. He/she lost all interest in things and is not motivated to do anything. He/she complains of often waking up in the middle of the night and not being able to get back to sleep. By the morning, he/she feels exhausted and without energy. He/she says that he/she encounters difficulty in concentrating on his/her job. Unlike before, everything takes him/her a very long time to do. He/she hardly manages his/her workload. As a consequence, he/she has already been summoned to his/her boss. AB has now sought professional help and was told he/she appears to be suffering from depression.

Vignette control

Imagine that you know the following about an acquaintance (CD) with whom you occasionally spend your leisure time.

Over time, your acquaintance has not particularly changed in his/her nature. Although he/she has his/her ups and downs like most people, he/she is generally pretty normal in how he/she acts. CD is usually agreeable, and has a sense of humor. His/her ideas and beliefs do not seem strange and he/she has a reasonable approach in his/her thinking about issues. He/she is usually comfortable interacting with other people. He/she seems to have as much confidence in himself/herself as most people do. CD’s mood is generally good and he/she is able to get on with the things in his/her life that need to be done. He/she is able to do his/her work. While he/she has his/her own unique characteristics and personality, people who know him/her would think that he/she is mentally and emotionally health.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Norman, R.M.G., Sorrentino, R.M., Windell, D. et al. The role of perceived norms in the stigmatization of mental illness. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 43, 851–859 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0375-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0375-4