Abstract

Background

Most needs of outpatients with schizophrenia are met by the family. This could cause high levels of family burden. The objective of this study is to assess the relationship between the patients’ needs and other clinical and disability variables and the level of family burden.

Method

A total sample of 231 randomly selected outpatients with schizophrenia was evaluated with the Camberwell Assessment of Needs, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, Global Assessment of Functioning and Disability Assessment Scale. A total of 147 caregivers also answered the objective and subjective family burden questionnaire (ECFOS-II). Correlations between total number of needs and family burden, t tests between presence or absence of need for each domain of family burden and regression models between family burden and needs, symptoms, disability and sociodemographic variables were computed.

Results

The number of patients’ needs was correlated with higher levels of family burden in daily life activities, disrupted behaviour and impact on caregiver’s daily routine. The patients’ needs most associated with family burden were daytime activities, drugs, benefits, self-care, alcohol, psychotic symptoms, money and looking after home. In a regression model, a higher number of needs, higher levels of psychopathology and disability, being male and older accounted for higher levels of family burden.

Conclusion

Patients with schizophrenia with more needs cause greater family burden but not more subjective concerns in family members. The presence of patients’ needs (daytime activities, alcohol and drug), severity of psychotic symptoms and disability are related to higher levels of family burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients [8] has implied that a large proportion of people with schizophrenia now live with their relatives, who are the main providers of social network and care [42]. Most needs of outpatients with schizophrenia previously met by psychiatric hospitals are now being covered by families [28]; especially those needs related to daily activities (food, looking after home, self-care, company, child care, money…) [31]. Formal services, meanwhile, cover areas where there are established services or intervention. This may show country variation. For example, in the Northern European countries, informal caregivers tend to have a less important role; this might be due to the wider scope of formal services and the more limited social networks of that area compared to Mediterranean countries [26]. However, Smith [40] in USA reported that a high number of families had the need for support services in the care of their ill relatives causing high levels of burden. Family burden is therefore an international problem and several programmes have been developed in order to reduce it [32].

These increased demands for family care have overlapped with a decrease in family size, which has reduced the capability of the families to provide care and support to their members.

There are two types of family burden: objective and subjective. Objective family burden is defined as the specific and observable implications in care, whilst subjective burden is defined as the concern about psychological consequences [12]. Different variables have been related to high levels of family burden as symptoms [20, 34] and social functioning [17]. Fadden [5] found that a higher presence of negative symptoms in patients was more related to high levels of family burden; Roick et al. [37] also found that negative and positive symptoms were explained by high levels of family burden. Moreover, Koukia and Madianos [17] found that patients with less social functioning cause more family burden.

However, studies about the relationship between patients’ needs and family burden are very scarce. The only study that we could find [25]showed limited relationship between the needs perceived by the patients and the burden of their caregivers. The authors explained that the questionnaire might not have collected all the information related to the needs and family care, and suggested that further research should be conducted. Our approach is to assess more deeply if patients with a higher number of needs, showing some specific needs, cause more family burden. Recently, our team has validated the Spanish version [43] of the Family Burden Interview Schedule-Short Form (FBIS-SF) [41] and this family burden questionnaire allows us to make a deeper assessment of objective and subjective family burden.

The aims of this study are: to assess the relationship between the number and type of expressed needs and family burden; and to assess the influence of symptoms and social functioning of the patient in the family burden of the relatives.

Methods

Sample

The sample selected was composed of 231 people with schizophrenia who were randomly selected from a computerized register that included all patients under treatment in the five mental health centres of Sant Joan de Déu that participated in the study. The five community mental health centres cover a catchment area of 440,000 adults of different sociodemographic backgrounds from the city of Barcelona and its surroundings and are representative of the community mental health centres of Catalonia (region of Spain), about 500 patients with schizophrenia are attending these mental health centres.

Inclusion criteria were (a) to have a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM-IV criteria, (b) to be between 18 and 65 years old, (c) to live in the catchment area, and (d) to have had at least one outpatient visit during the 6 months prior to the start of the study. Patients with a diagnosis of mental retardation or neurological disorder were excluded.

The selected subjects were informed by their psychiatrist about the objectives and methodology of the study and provided verbal informed consent to participate. They also gave the investigators permission to contact their key-relative to analyse family burden.

Material

Assessment of patients

Demographical and clinical information on the subjects was gathered with the following instruments:

-

A sociodemographic and clinical questionnaire that included information on psychiatric history and comorbidity.

-

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [16]; Spanish version [33]. The PANSS items were classified into four clusters (negative, positive, excitative and depressive factor) following the results obtained with this sample [44].

-

The Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS-s), short version [14]. This scale includes assessment of disability in four areas: self-care, occupational, family and social disability.

-

The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) [4].

-

The Camberwell Assessment of Needs (CAN) [35], Spanish Version [24, 38] which assesses the presence of needs in 22 areas. In this study we have used the patients’ assessment.

Family assessment

The main caregiver defined by the patient was the object of the assessment of family burden.

Family burden was assessed with the Objective and Subjective Family Burden Interview (ECFOS-II), validated into a Spanish version by our group [44]. This instrument was developed based on “The FBIS-SF” [41]. The alpha Cronbach coefficient was 0.85 and the Cohen’s Kappa coefficients ranged between 0.61 and 1. The instrument includes nine modules assessing different areas of possible burden: module A, activities of daily life; module B, supervision and disrupted behaviours; module C, costs; module D, impact on caregiver’s daily life; module E, concerns; module F, hours of help given by another caregiver; module G, repercussions on the caregiver’s health (psychoactive medication); module H, global information given by the caregiver and module I, global information given by the interviewer. For the purpose of our study, we have used data from four modules: care given to the activities of daily life (A), supervision of disrupted behaviours (B), impact on caregiver’s daily life (D) and concerns (E). We have selected these modules as each of them is composed by more than four items which have been summarized in quantitative variables. These summaries give information about subjective and objective direct burden.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 11.0 [29].

Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to describe the association between the objective and subjective burden mean scores in activities of daily life, supervision of disrupted behaviours, impact on caregiver’s daily routine and caregiver’s concerns modules and number of total, met and unmet needs.

The comparison of the level of burden in each of the modules and patients’ needs in the 22 domains analysed with the CAN was based on a mean comparison and Student’s T Statistic. When the distribution of the groups was not normal, we used non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U test).

Finally, to study the effects of age, age at onset, sex, GAF, PANSS subscales (positive, negative, excitative and depressive) and DAS-S subscales (self-care, occupational, family and social disability) with total number of needs on the level of burden in the ECFOS-II modules, a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was performed. The selection of variables included in the regression model was based on statistical and literature findings.

Results

Of the 231 patients selected initially, we fulfilled the whole assessment of 196 of them, but there were no significant differences in any of the sociodemographic variables between the people who answered all the questionnaires and those who did not. The reasons why people did not fulfill the assessment were: 30 (13%) the lack of compliance with all the visits and 5 (2%) of them moved outside the catchment area of the community mental health centre.

Approximately two-thirds (63.6%) were male. Mean age was 39 years old (SD = 12.1) and mean length of illness 16 (SD = 10) years. Patients were more often single (66.7%), lived with parents (50.6%) and were not working because they were on permanent sick leave (66.2%). Mean GAF score was of 43.42 (SD = 13). Mean DAS-s total score was 10.96 (SD = 4.3) (Table 1).

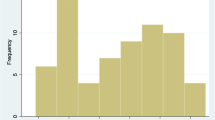

Mean number of needs was 5.36 (SD = 2.71), whilst mean number of unmet needs was 1.82 (SD = 1.98). The most frequently detected needs were psychotic symptoms (68%), looking after home (50%), food (46%) and information (42%) while the unmet needs involved company (22%), intimate relationship (17%) and daytime activities (13%).

Only 147 key-relatives of the 196 people with schizophrenia who were assessed for the study were available and willing to participate (75%). The main reasons for not answering the questionnaire were: absence of family (13%), the patient was the head of the household (3.9%), refusal of the family or the patient to attend the interview (3.6%), and other reasons (4.5%). There were no differences in sociodemographic, clinical, social functioning and needs variables of patients whose relatives were interviewed and those who were not.

The main caregivers of patients interviewed were: their parents (58.5%)—mainly their mothers (48.3%)— followed by their partners (17.7%), siblings (12.9%) and offspring (9.5%) and other relatives (1.4%). The mean age of the caregivers was 62.77 (SD = 10.10).

The highest levels of burden were found in the modules of concerns and in the objective care given with the activities of daily life (Table 2). The average frequency of care given for activities of daily life was about once or twice per week. Supervision of disrupted behaviours was about once a week. We also observed that the patient’s disorder interfered in the caregiver’s life about once a week.

The highest level of objective family burden in caregivers was found in areas such as meals (67%), housework (61%) and managing money (53%) (belonging to the activities of daily life module). Subjective family burden was high in the following domains: future (99%), security (92%), money (90%), physical health (85%) and social life (81%) (all belonging to the concerns module).

We found a positive correlation between objective and subjective burden in care provided in the activities of daily life, subjective burden of disrupted behaviours and the impact on caregivers’ daily routine with the patients’ total number of needs. The same relationship was observed between the modules above and the met needs, but met needs were also associated with subjective burden in disrupted behaviours. We found no relationship between the family burden and the patients’ unmet needs (Table 3).

Table 4 describes the relationship between family burden and the presence or absence of different type of needs. The table only reports on the needs that have a statistically significant relationship with burden (P < 0.05). A high level of family burden in activities of daily life was observed in people who reported needs in the following domains: food, looking after home, self-care, daytime activities, drugs, money and benefits. Relatives of patients with needs in daytime activities, self-safety, alcohol and drugs proved a higher burden in disrupted behaviour. Relatives scored higher in concerns when patients showed needs in the areas of daytime activities and psychotic symptoms.

Multiple linear regression models were used to determine which of the sociodemographic variables, symptoms, social functioning and needs of patients explain objective and subjective burden. The models with a higher explanatory value as measured with R 2 were those explaining the objective burden family modules. Objective family burden in activities of daily life were explained by GAF, total number of needs, self-care DAS-s subscale, the positive subscale of the PANSS and gender (worse family burden in men); whilst subjective family burden in this module was explained by the negative subscale of the PANSS and the total number of met needs. The objective burden caused by disrupted behaviours was associated with the total number of needs, the DAS-s family functioning subscale and excitative PANSS. Disrupted behaviours subjective burden was related to DAS-s family functioning subscale and age. The impact on caregivers in the daily routine module was explained by the total number of needs, the DAS-s family functioning subscale and the affective subscale of the PANSS. Finally, the concerns of caregivers were explained by occupational disability, age, negative subscale of the PANSS and age at onset (Table 5).

Discussion

A clear relationship between subjective and objective family burden of relatives of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and the needs showed by the patients is found in our study. Relatives show high levels of burden when patients have some specific needs that require to be met.

No relationship was found between unmet needs and family burden. It is possible that we do not find any correlation because of the small number of patients with unmet needs.

Our results suggest that people who have more needs in food, looking after home, daytime activities, self-care and social benefits cause a higher family burden in the daily life activities of the caregivers. Families have to look after and supervise the activities of their ill relatives in daily life. Caregivers were mainly the patients’ mothers, coinciding with other studies[10].

Disrupted behaviours in the supervision module of family burden are related to the presence of needs in the areas of drugs and alcohol; drugs are related to a higher family burden in activities of daily life, too. It is clear that outpatients with problems in the drugs domain cause a higher family burden. Specific interventions should therefore be made in the case of patients with schizophrenia who have problems with drugs and alcohol use in order to reduce the family burden [39].

These findings are interesting because they can help us determine a profile of patient who can cause a higher family burden and it would allow us to define interventions to their families.

However, no relationship was found between the concerns module and the total number of needs. This means that the concerns of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia are present regardless of the existence of patients’ needs. These results coincide partially with Meier et al. [25], they did not find any relationship between subjective family burden and the patient’s needs. The authors suggest that a wider assessment of family burden should be done; our study has assessed family burden with a more extensive questionnaire (ECFOS-II) and other aspects of subjective and objective family burden have proved to be related with the patient’s needs. Foldemo et al. [7] suggests that caregivers are worried about what will happen to the patients when they are no longer able to help them, which is actually consistent with the high levels of concern about the future found in our study.

Family burden is also related to symptoms and disability of their ill relative. These results are consistent with those of Magliano et al. [21], because they found that levels of family burden are lower when patients improve their social functioning. However, Möller-Leimkükhler [27] found that the patient’s symptoms and psychosocial functioning were not related to family burden in individuals with a first psychotic disorder and with depression. Thus, the positive results found in our sample show that family burden could be associated with a chronic course of the illness and caregivers could be more tolerant at the onset of the disorder. Interventions in early psychosis should be carried out to avoid the patient’s condition becoming chronic. These interventions on early psychosis should aim to improve the patients’ work abilities [36], reduce their social disability and stigma [9] and support the family [2].

Our results show that a higher severity of negative and positive symptoms is related to higher levels of family burden in the area of daily life. Other authors [1, 15] found that negative symptoms were related to higher levels of family burden. In addition, we have found that excitative symptoms are related to the supervision module of family burden and depressive symptoms are related to concerns.

Men cause more objective family burden in the areas of daily life than women. Caregivers spend more time helping male patients than female patients in this area. As a result of the different social roles between women and men, women are more likely to be trained by their families than men to perform this task. This result is consistent with the findings of a previous study [30].

One of the limitations of our study is that we do not have information of about more than 30% of the sample. However, when we assess the differences on sociodemographic and needs variables, there are no significant differences. Therefore, we expect that there are not any differences between the samples.

Conclusion

In conclusion, parallel interventions should be done with patients with schizophrenia and with their families. First, mental health services should pay attention to meet the patients’ needs, specially those related to daytime activities, drugs and alcohol. Secondly, services should try to reduce disability and severity of symptoms. One possibility to detect these problems would consist in carrying out routine outcome assessments to assess these areas of the patients (CAN or CANSAS; PANSS and DAS-sv). Third, care giving families of people with schizophrenia with high levels of needs should receive more help from the formal services. Our results support the suggestions of Magliano et al. [22, 23] that caregivers of patients with schizophrenia need more support from the mental health services. They suggest that these services should train caregivers in different strategies for managing their psychological reactions to the patient’s illness, they should educate them about the patient’s disease and reinforce their network. There are different possible interventions to effectively reduce the concerns and anxieties of caregivers [2, 6, 13, 18, 19], and they should perhaps be applied in all cases where the family is meeting the needs of outpatients with schizophrenia.

References

Addington J, Collins A, Mc Cleery A, et al. (2005) The role of family work in early psychosis. Schizophr Res 1; 79(1):77–83

Berglund N, Valhne JO, Edman A (2003) Family intervention in schizophrenia-impact on family burden attitude. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38(3):116–121

Dyck DG, Short R, Vitaliano PP (1999) Predictors of burden and infectious illness in schizophrenia caregivers. Psychosom Med 61(4):411–419

Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al. (1976) The global assessment scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 33:766–771

Fadden G, Bebbington P, Kuipers L (1987) The burden of care: the impact of functional psychiatric illness on the patient’s family. Br J Psychiatry 150:285–292

Fallon IRM, Roncone R, Held T, et al. (2001) An international overview of family interventions: developing effective treatment strategies and measuring their benefits for patients, carers and communities. In: Lefles HP, Johnson DL (eds) Family intervention in mental illness: international perspectives. Praeger, Greenwood

Foldemo A, Gullberg M, Ek AC, et al. (2005) Quality of life and burden in parents of outpatients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:133–138

Garcia J, Vazquez-Barquero J (1999) Deinstitutionalization and psychiatric reform in Spain. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 27(5):281–291

González-Torres MA, et al. (2007) Stigma and discrimination towards people with schizophrenia and their family members. A qualitative study with focus group. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42(1):14–23

Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Caqueo-Urizar A, Kavanagh DJ (2005) Burden of care and general health in families of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40(11):899–904

Hazel NA, McDonell MG, Short RA, et al. (2004) Impact of multiple family groups of outpatients with schizophrenia on caregivers’ distress and resources. Psychiatr Serv 55(1):35–41

Hoening J, Hamilton M (1966) The schizophrenic patient and his effect on household. Int J Soc Psychiatry 12:165–176

Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, et al. (1991) Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia. II. Two-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and adjustment. Environmental-personal indicators in the course of schizophrenia (EPICS) research group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48(4):340–347

Janca A, Kastup M, Katchming H, et al. (1996) The world health organisation short disability assessment schedule (WHO-DAS-S): a tool for the assessment of difficulties in selected areas of functioning of patients with mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 31:349–354

Joseph R, Birchwood M (2005) The national policy reforms for mental health services and the story of early intervention services in the United Kingdom. J Psychiatry Neurosci 30(5): 362–365

Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A (1986) The positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS). Rating manual. Soc Behav Sci Doc 17:28–29

Koukia E, Madianos MG (2005) Is psychosocial rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients preventing family burden? A comparative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 12(4):415–422

Leff J (1994) Working with the families of schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 164(Suppl 23):71–76

Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM (1998) Translating research into practice: the schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophr Bull 24(1):1–10

Lowick B, De Hert M, Peeters E, Wampers M, Gilis P, Peuskens J (2004) A study of the family burden of 150 family members of schizophrenic patients. Eur Psychiatry 19(7):395–401

Magliano L, Fadden G, Economou M, et al. (2000) Family burden and coping strategies in schizophrenia: 1-year follow-up data from the BIOMED I study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 35(3):109–115

Magliano L, Malangone C, Guarneri M, et al. (2001) The condition of families of patients with schizophrenia in Italy: burden, social network and professional support. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 10(2):96–106

Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Rosa C, et al. (2006) Family burden and social network in schizophrenia vs. physical diseases: preliminary results from an Italian national study. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 429:60–63

Mc Crone P, Leese M, Thornicroft G, et al. (2000) Reliability of the Camberwell assessment of need-European version. Br J Psychiatry 177(39):s34–s40

Meier K, Schene A, Koeter M, et al. (2004) Needs for care of outpatients with schizophrenia and the consequences of their informal caregivers. Results from the EPSILON multi centre study on schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:251–258

Middelboe T, Mackeprang T, Hansson L, et al. (2001) Nordic Study of patients with schizophrenia who live in community. Eur Psychiatry 16:207–215

Möller-Leimkükhler AM (2005) Burden of relatives and predictors of burden. Baseline results from the Munich 5-year-follow-up study on relatives of first hospitalised patients with schizophrenia and depression. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 225:223–231

Moreno Kustner B, Jimenez Estevez JF, Godoy Garcia JF, et al. (2003) Assessment of needs for care of a schizophrenic patient sample from the Granada Sur Mental Health Care Area. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 31(6):325–330

Norusis M (1993) SPSS para Windows. Versión 11.0 Guía del usuario, Madrid

Ochoa S, Usall J, Haro JM, et al. (2001) Estudio comparativo de las necesidades de las personas con esquizofrenia en función del género. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 29(3):165–171

Ochoa S, Haro JM, Autonell J, et al. (2003) Met and unmet needs of Patients with schizophrenia in Spanish sample. Schizophr Bull 29(2):201–210

Penn DL, Mueser KT (1996) Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 153(5): 607–617

Peralta V, Cuesta JM (1994) Validación de la escala de síndromes positivo y negativo (PANSS) en una muestra de esquizofrénicos españoles. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 22:171–177

Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Kaczynski R, Swartz MS, Canive JM, Lieberman JA (2006) Components and correlates of family burden in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 57(8):1117–1125

Phelan M, Slade M, Thornicroft G, et al. (1995) The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN): the validity and reliability of an instrument to assess the needs of people with severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 167:589–595

Provencher HL, Mueser KT (1997) Positive and negative symptom behaviors and caregiver burden in the relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 25; 26(1):71–80

Roick C, Heider D, Toumi M, Angermeyer MC (2006) The impact of caregivers’ characteristics, patients’ conditions and regional differences on family burden in schizophrenia: a longitudinal analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 114(5):363–374

Rosales C, Torres F, Luna J, et al. (2002) Fiabilidad del instrumento de evaluación de necesidades Camberwell (CAN). Actas Esp Psiquiatr 30(2):99–104

Rosenfarb IS, Bellack AS, Aziz N (2006) A sociocultural stress, appraisal, and coping model of subjective burden and family attitudes toward patients with schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 115(1):157–165

Smith GC (2003) Patterns and predictors of service use and unmet needs among aging families of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 54(6):817–817

Tessler RT, Gamache GM (1995) Toolkit for evaluation family experience with severe mental illness. Human Services Research Institute, Cambridge

Tucker C, Barker A, Gregorie A (1998) Living with schizophrenia: caring for a person with a severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33:305–309

Vilaplana M, Ochoa S, Martínez A, et al. (2007) Validación en población española de la entrevista de carga familiar objetiva y subjetiva (ECFOS-II) para familiares de personas con esquizofrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 35(6):372–381

Villalta-Gil V, Vilaplana M, Ochoa S, et al. (2006) Four symptom dimensions in schizophrenia outpatients. Compr Psychiatry 47(5):384–388

Acknowledgements

This project has received the financial help of the Spanish “Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias” (FIS 97/1275); RIRAG Network (RETICS FIS G03/061); the Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, CIBER-SAM, and the Fundació Marató de TV3 (013610).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The NEDES group is a multidisciplinary group of researchers from Sant Joan de Déu, which includes: S. Araya; P. Asensio; J. Autonell; A. Benito; E. Busquets; C. Carmona; P. Casacuberta; M. Castro; N. Díaz; M. Dolz; A. Foix; J. M. Giralt; A. Gost; J. M. Haro; M. Marquez; F. Martínez; R. Martínez; J. Miguel; M. C. Negredo; S. Ochoa; Y. Osorio; E. Paniego; L. Pantinat; A. Pendàs; C. Pujol; J. Quilez; J. Ramon; M. J. Rodríguez; B. Sánchez; A. Soler; F. Teba; N. Tous; J. Usall; M. Valdelomar; J. Vaquer; E. Vicens; M. Zamora.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ochoa, S., Vilaplana, M., Haro, J.M. et al. Do needs, symptoms or disability of outpatients with schizophrenia influence family burden?. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 43, 612–618 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0337-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0337-x