Abstract

Background

Measurement of service content is necessary to understand what services actually provide and explain variation in service outcomes. There is no consensus about how to measure content of care in mental health services.

Method

Content of care measures for use in mental health services were identified through a search of electronic databases, hand searching of references from selected studies and consultation with experts in the field. Measures are presented in an organising methodological framework. Studies which introduced or cited the measures were read and investigations of empirical associations between content of care and outcomes were identified.

Results

Twenty five measures of content of care were identified, which used three different data collection methods and five information sources. Seven of these measures have been used to identify links between content of care and outcomes, most commonly in Assertive Community Treatment settings.

Discussion

Measures have been developed which can provide information about service content. However, there is a need for measures to demonstrate more clearly a theoretical or empirical basis, robust psychometric properties and feasibility in a range of service settings. Further comparison of the feasibility and reliability of different measurement methods is needed. Contradictory findings of associations between service content and outcomes may reflect measures’ uncertain reliability, or that crucial process variables are not being measured.

Conclusion

Measures providing a greater depth of information about the nature of interventions are needed. In the absence of a gold standard content of care measure, a multi-methods approach should be adopted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The importance of understanding what actually happens in mental health care delivery is increasingly recognised. There is considerable variation in practice even amongst similarly labelled mental health services [13], such as case management teams [9]. Detailed investigation of the content of service interventions is therefore needed if differences in outcomes between services are to be understood [31]. However, a lack of complete or consistent approaches to describing mental health services has been identified [13]. It has been argued that valid measurement of the content of care provided to patients may be more crucial than attending to service style, setting or organisation in understanding the links between service processes and outcomes [25].

The place within mental health services research of measurement of the content of care at services can be identified with reference to existing conceptual frameworks. The Mental Health Matrix, for example, proposes two dimensions to formulate mental health service aims and practice [49]. In a temporal dimension, it distinguishes the process of care at services from the inputs and resources of a service and service outcomes. In a geographical dimension, care provided to patients within a service, by a local service system, or at a regional/national level can be distinguished. Within this framework, content of care measurement concerns the process of care at a patient level.

Measurement of the content of mental health services, including both the quantity and nature of interventions delivered to patients, can be identified as one of four ways in which mental health services have been described and classified [25], distinguishing service content from the style, setting or organisation of services. Description of the content of mental health services can be separated into several elements [6]—the nature, frequency, duration, scope, setting and style of care or “how much of what is done to whom, when and in what manner” [6, p. 284].

The concept of service content can thus be used to refer to the sum of what staff provide for patients at a service. The term “content of care” will be used for this purpose in this review. It will include both direct care: what staff do when they see patients and indirect care: what staff provide for patients in their absence. Arguably, content of care is a harder concept to define or measure than broader variables such as service type or specific single interventions such as pharmacological treatment. The clarity provided by valid measurement tools is consequently particularly needed.

There are at least five reasons to assess content of care in mental health services:

-

(i)

To describe service content. Measurement of the content of care in services can identify differences in content provided by a service over time, between services, or to different groups of patients within a service [6].

-

(ii)

To measure model fidelity. If established guidelines or operational criteria exist regarding the model of care to which a service is seeking to work, measurement of service content can be used to assess model fidelity and programme implementation [43].

-

(iii)

To understand service outcomes. While not providing certainty, it can help generate hypotheses to explain service outcomes and identify active ingredients of complex interventions [25].

-

(iv)

To understand variation in patient outcomes. Attending to what works for whom—identifying variation in the effectiveness of different service interventions for different groups of patients—has been advocated [37]. Patient level data about care received can help investigate this by illuminating whether variation in outcomes for groups of patients within a service may be due to differences in responsiveness to interventions or differences in interventions received.

-

(v)

To assess service quality. If an element of service content has already been clearly demonstrated to produce good outcomes, it can be used as a measure of effectiveness or service quality [18].

Qualitative measures of content of care and quantitative measures of related variables can provide information about service content, but only to a limited extent. Three qualitative methods of inquiry in mental health research—in-depth interviews, focus groups and participant observation—have been identified [53], all of which can provide rich information about what happens at mental health services and how care is experienced. However, qualitative methods are ill-suited to comparing differences, potentially small but significant, in the number or types of interventions provided to representative groups of service users at services. In order to investigate associations between care provided and service outcomes and provide an empirical basis for identifying active ingredients of care, quantitative data is required.

Quantitative outcome measures may be used to draw inferences about the care provided at services. Most pertinently, measures of need such as The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) [47], can be used to measure whether a service user’s needs in different areas are met during a period of care, from either the service user’s, carer’s or staff’s perspective. As an outcome measure, however, the CAN is limited as a process measure of content of care for the following reasons:

-

(i)

It measures the effectiveness of care, not its provision. If someone receives considerable help with psychotic symptoms, which are not alleviated, for instance, this would be recorded in CAN as an unmet need, offering no record that care has been provided.

-

(ii)

It measures whether needs are met but not how. For example, it is unclear whether someone with a met need for psychotic symptoms has received pharmacological or psychological treatment, or of what sort.

-

(iii)

It provides little scope for differentiating how much care has been provided to individuals or at services. Inpatient care is always recorded as high-level care for example.

Specific quantitative measures of content of care are therefore required to measure what is provided in mental health services. Two organising frameworks, drawn from social research literature, can be applied to describe ways of measuring content of care:

-

(1)

Source of information. Four sources of data for process measurement of social programmes or health services have been identified [42]:

-

(1)

direct observation by the researcher;

-

(2)

information from service records;

-

(3)

data from service providers;

-

(4)

data from service users. Measures may use a combination of data sources and have;

-

(5)

a mixed information source.

-

(1)

-

(2)

Method of data collection. Two ways of conceptualising how to record activity are: recording in terms of time or in terms of incidents [11]. Time recording involves recording whatever is happening over a given period of time (instants, short periods or longer, continuous time periods) to specified person(s) or in a specified area. Incident Recording involves pre-selecting particular event(s) of interest and recording if and when these happen over a given period of time.

A further distinction can be made between contemporaneous and retrospective incident recording. Here, the term Event Recording is used to describe methods of recording incidents at or very near the time they happen. Retrospective Questionnaires (completed by staff, patients, or researchers based on interviews, observation or reference to case records) is used to describe information about events of interest gathered retrospectively.

This literature review aims to identify existing measures of the content of care in mental health services. The measurement methods they employ will be presented. The empirical associations between content of care and outcomes found using the measures will be summarised and how far existing measures are able to meet the goals of content of care measurement will be considered. What is known about how best to measure the content of care in mental health services and directions for future research will be discussed.

Method

Identifying measures of content of care

Inclusion criteria

Measures were included which provide quantitative data about the amount and types of care provided at any type of specialist inpatient, residential or community mental health service for adults. Measures, which provided this information, despite having a different primary purpose (e.g. to measure patient activity or model fidelity) were included. Measures providing service level information only and measures providing individual patient level information, which could be aggregated to provide service information, were both included. Measures of direct care only or direct and indirect care were included.

Measures were excluded which assess related process factors (e.g. psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy rating scales, measures of continuity of care, service style, model fidelity or service quality) but do not assess provision of the amount and types of care.

Search strategy

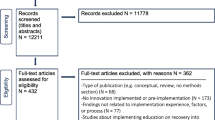

The literature involving content of care measures does not use a consistent terminology and thus does not lend itself to straightforward retrieval from bibliographic databases. This review therefore uses a variety of methods to identify relevant studies.

-

(i)

Medical and nursing electronic databases (Pubmed, Embase, PsycInfo, Cinahl) were searched using a Medical Subject Heading of “mental health services” or equivalent, combined with (1) generic terms for the content of mental health services—“content of care” or “process of care” or “process measure” in title or abstract; or (2) terms for specific methods of process measurement identified from reference works—“time recording” or “time sampling” or “time budget” or “event recording” or “incident recording”. Publications from 1966–2006 were included in the search.

-

(ii)

Reference lists from relevant studies identified in the electronic search were hand searched.

-

(iii)

A group of six accessible experts involved in previous studies of content of care was asked for information on current studies or methodological approaches to content of care measurement in mental health services.

Data abstraction

The following characteristics of measures identified in this review were collected:

-

(i)

Data collection method

-

(ii)

Information source

-

(iii)

Level of information provided: patient = care provided to individual patients; service = overall care provided at a service

-

(iv)

Service settings the measure has been designed for/used in

-

(v)

Established psychometric properties of the measure

Identifying the use of measures in process/outcomes investigation

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included in this part of the review if they used of one of the measures of content of care identified in this review to investigate associations between a defined content of care variable and subsequent inpatient admissions, clinical or social functioning or patient satisfaction.

Search strategy

-

(i)

Studies presenting the measures included in this review were read in order to identify whether the measure had been used to investigate associations between content of care variables and outcomes.

-

(ii)

Articles citing the above studies were identified through an electronic database. (No single database provided citations for all studies: Web of Science, PsycInfo and GoogleScholar were used.). These articles were also read to find any investigation of content of care/outcome associations using identified measures.

Data abstraction

The following information was collected about identified studies investigating associations between content of care and outcome:

-

(i)

Content of care variable measured

-

(ii)

Outcome variable measured

-

(iii)

Study setting

-

(iv)

Was an association between content of care and outcomes identified?

-

(v)

Study reference

Results

25 measures of content of care were identified for inclusion in this review. The methods used by these measures are summarised in Table 1.

Titles and references for the individual measures are provided in sections i–iii below. The characteristics of measures are also described in these sections, grouped by data collection method.

(i) Event recording measures

6 event recording measures were identified (see Table 2).

Measures ask individual staff to record only their own contacts with clients, with the exception of the structured record described by Patmore and Weaver [35], which requires one respondent to record all interventions received by a client from any member of staff at a service during the recording period.

Event Recording measures have only been used in community services. They vary in terms of:

-

Collection method: All measures use paper recording forms except The Event Report [23], which required staff to use a pocket computer to complete daily records.

-

Scope of information: Measures provide information about the content of care within a single service, except for The Mannheim Service Recording Sheet [44], which provides information about patients’ use of the whole local mental health system.

-

Depth of information: Measures record either face-to-face staff/patient contacts only [44] or a variety of types of staff activity, e.g. face-to-face, telephone or failed contact with a patient, contact with a carer and contact with another professional [12]. The nature/purpose of an intervention is categorised in measures as one of between 5 and 11 defined types of care (e.g. help with housing, medication review etc).

The psychometric properties of Event Recording measures have not been examined thoroughly. Only the Daily Contact Log [6] has been investigated regarding inter-rater reliability, through clinicians’ ratings of case note vignettes and use of the measure in vivo by staff and researcher, following direct observation of clinical practice. Face validity alone has been established for the variables used in the measures.

Three rationales have been identified for the categorisation of types of care in event recording measures: (1) consistency with another established measure: e.g. The Mannheim Service Recording Sheet [44] mirrors the categories used in the International Classification of Mental Health Services [16]; (2) consistency with an established model of care: e.g. the Event Report [23] measures elements of Integrated Care, a model of care for people with schizophrenia [19]; (3) describing actual service practice: e.g. The Event Record [12] categories are informed by a rigorous Delphi Process with Intensive Case Managers [20], to ensure adequate and accurate reflection of their work practices.

(ii) Time recording measures

11 time recording measures were identified (see Table 3).

Measures record activity at a service at specific moments, during short periods of between 5 and 15 min, or continuously over whole days or shifts. They all provide information about the number of staff-patient interactions, although the main purpose of the measure may be to measure these interactions [14, 36, 45]; all staff activity [24, 35, 52, 55]; or all patient activity [5, 24, 27, 54]. All measures employ a paper recording method, but display a variety of approaches regarding:

-

Scope of information: Researcher-observation measures record activity within a defined, observable area within a residential or inpatient service. Staff-report measures provide information about all activity within a service.

-

Depth of information: Only the staff-completed time recording measures categorise the types of care provided in similar detail to event recording measures. Measures of staff activity distinguish different types of activity: for example, direct patient contact, indirect patient care, administrative work (e.g., record keeping) and other activity [24]. A number of observational measures record information about the quality of staff contacts with patients: for example rating them as accepting, tolerating or rejecting [45].

Inter-rater reliability testing of several researcher-observation based time recording measures indicate that observers can reliably identify what constitutes a staff-patient contact and rate whether that contact is positive, negative or neutral in nature. The reliability of staff-report time recording measures has not been tested.

No empirical basis for choice of categories of staff activity has been reported for any time recording measure beyond basic face validity. Only Wing and Brown report testing the construct validity of their measure [54]: time spent doing nothing, not engaged with staff or others, as measured by the Time Budget, did correlate with four other measures of poverty of the social environment.

(iii) Retrospective questionnaire measures

8 retrospective questionnaire measures were identified (see Table 4).

Information about the amount and types of care is obtained from a variety of information sources, but all measures are completed by researchers, bar the staff-completed measure of Kovess and Lafleche [28]. Two measures [48, 56], are primarily designed to measure services’ model fidelity and one measure [2] to measure service cost, but all can provide information about service content. Retrospective questionnaires recording content of care vary regarding:

-

Recording period: Measures are completed retrospectively for time periods varying from 1 month [2, 26] to 18 months [22].

-

Scope of information: Measures provide information about the content of care provided across a service system [2, 26], or within one service.

-

Depth of information: Of the retrospective questionnaire measures providing individual patient-level information, only two [2, 38] assess the specific number of interventions received by individuals. All retrospective questionnaires provide a measure of the amount of care provided at services, except the ICMHC [16], which however identifies 10 different types of care, the most detailed information provided by a retrospective measure about the nature of care at services.

Demonstration of the psychometric properties of retrospective questionnaire content of care measures has not been extensive. The I.C.M.H.C., which has been demonstrated to have good inter-rater reliability [15], provides service level information about types of care only.

Content of care and outcome

7 measures included in this review were identified as having been used to investigate the association between content of care variables relating to amount, setting or nature of care and patient outcomes. These investigations are summarised in Table 5.

Of 13 studies described here, 11 involve community-based services, 9 are of American services and 9 involve Assertive Community Treatment or proto-ACT services. The effect of the amount of staff-patient contact has been most widely investigated.

Discussion

This review has identified 25 measures of content of care in mental health services which use 6 different measurement methods. 7 measures have been used to investigate empirical associations between service content and outcomes.

Measures of content of care have been developed and used in a variety of service settings and offer a way to understand what services actually provide. This would not be possible through outcome studies alone. Progress in developing measures of content of care has been far from linear however. There is variation in existing measures regarding what is measured (direct care only or direct and indirect care) and how it is measured. The methodological framework presented in Table 1 shows that only a minority of possible methods of measuring content of care have been used in measures described in this review. This review finds that many measures lack a clear theoretical or empirical basis and/or have not been tested for psychometric properties. Many measures have been developed and used for a particular study, but not applied or further developed in future studies or different settings.

Where the association between content of care variables and outcomes has been investigated, findings have varied. Conflicting evidence exists, for example, for the most widely examined questions: whether amount of care [7, 8, 12, 17, 29] or ACT fidelity [3, 29, 30] in community-based services affect inpatient bed use.

The lack of repeated, consistent demonstration of association between any content of care variable and patient outcomes in part reflects the inherent difficulties this type of investigation, where numerous confounding factors other than received care will affect patients’ subsequent health status [10]. It is not implausible, for example, that severity of illness could be associated with increased amount of treatment and poorer health outcomes for patients at a service. It is possible however, that the uncertain reliability of content of care measures used has obfuscated associations with outcomes, or that appropriate content of care variables have not measured. This review found that the majority of studies of process and outcome associations concerned the link between amount of direct care and outcomes. Studies, which assess what staff actually do when they see patients, to investigate links between the nature of care provided and outcomes, remain rare.

The need for effective content of care measurement in mental health services research has been highlighted repeatedly [10, 13, 31]. Criteria for effective content of care measurement, encompassing psychometric robustness, comprehensiveness, clinical credibility and feasibility, have been proposed [18, 51]. However, current measures of content of care in mental health services only partially meet these criteria. The following are four challenges to more effective content of care measurement:

Psychometric robustness

Evidence of inter-rater reliability has been provided most clearly and consistently for researcher-completed direct observation measures, which, however, provide more limited information about the mature of care provided than most other measures in this review. Whether a greater depth of information, or information from sources other than researcher observation, can be obtained as reliably, remains unclear. The work of Brekke [6] suggests that staff-report event recording measures can provide reliable information about the nature and amount of staff-patient contact at services [6], but the reliability of his Daily Contact Log has yet to be similarly demonstrated for other staff-report measures.

There are also obstacles, whatever methodological approach is used, to creating a valid measure, which accurately assesses significant elements of content of care. Case note extraction measures may rely on incomplete or inaccurate source material, as found in a study comparing information obtained from patient interviews and case notes [56]. Other retrospective questionnaires may be compromised by respondents’ recall bias. All contemporaneous measures, meanwhile, may generate reactivity [32], i.e. where the process of measurement changes what is being measured. Participating in a research study, for example, could lead to a temporary increase in staff activity for the duration of a study. Staff-completed measures may also be vulnerable to deliberate distortion, to present a service in a good light.

The extent or comparative impact of these factors on the validity of different methods or measures is difficult to assess. A multi-methods and measures approach to assessing content of care may therefore be helpful: consistent findings from different measures could afford each a degree of convergent validity. This review suggests such an approach is rare, however: in practice, a measure is often developed for a specific study or service setting and used in isolation. The demonstration of clear links between service content and expected outcomes would also increase confidence that valid process variables are being accurately measured, but has also been rare.

Depth of information

A reasonable depth of information about the nature of care and types of intervention provided at services is necessary to understand what services actually do and begin to investigate what works for whom. Of the measures identified in this review however, even a comparatively informative measure with a clear theoretical basis (a Delphi Process with intensive case managers [20]), such as The Event Record [12], contains categorisations of types of care whose meaning is hard to infer—e.g. “specific mental health intervention”. Other examples of descriptions of types of care whose breadth compromises clarity include: “Support” [23]; “Follow up” [21]; “1:1” [6].

This review found that studies of content of care in inpatient mental health services have assessed the amount and quality of care, but no measure designed for and used in inpatient settings describes the types of intervention provided. The paucity of our understanding of what happens in UK inpatient mental health wards has been highlighted [39]: however, there is no measure of inpatient service content with sufficient depth to help address this issue. If feasible and reliable measures could be developed to provide a greater specificity and depth of information about care provided at services than is currently possible, this would aid attempts to describe and distinguish services.

Feasibility

Content of care measures need to generate adequate completion rates to provide high quality information. Researcher-completed measures may be assumed to pose fewest obvious problems regarding completion rates. An adequate response rate (66%) has been reported for a contemporaneous staff-report measure [35], but most studies of staff-report content of care measures do not report a response rate. A good response rate (85%) has been reported for a staff-completed momentary time recording measure in an HIV case management setting [1], indicating this could be a useful method for mental health settings.

The difficulty of obtaining contemporaneous, staff-report data could potentially be greater in residential settings than community services, owing to staff’s more numerous, briefer interactions with patients. However, we currently lack evidence with which to compare the feasibility of different methods of measuring content of care in similar service settings, or of any one measure in different service settings. It is also uncertain whether there are trade-offs between duration and depth of data collected from staff or service user-completed measures, i.e. whether respondents would be prepared to complete a lengthier or more complex measure for a limited period of time.

The proposals of this review, that a multi methods approach including using staff and service-user completed data be adopted and measures providing a greater depth of information be developed, would only increase the challenge of retaining feasibility in content of care measurement. Existing measures of content of care have been used to a great extent during research studies rather than in normal clinical practice: it may not be possible to create a measure of content of care which provides sufficient depth of information to be useful but is brief and simple enough to be acceptable for routine use in clinical settings.

Accounting for different perspectives

Few measures identified in this review include any information gathered from patient-report and none exclusively. This seems hard to justify: the experience of care received has as much face validity as a measure of content of care as the perception of care provided. Glick and colleagues most explicitly seek to include different perspectives [22], collecting information about care provided from physician, patient and carer. However, they then seek to reconcile discrepancies between accounts, without reporting how this was achieved. It is not self-evident that differences in the perception of care provided between staff and patients can or should be reconciled. Measures of patients’ needs [46], or the style of service [41], for instance, have identified significant differences between the views of staff and patients. Whether there are significant differences in consumers’ and providers’ perceptions of the content of care in mental health services and whether any such differences are constant in different services remain to be researched.

Conclusion

Measures have been developed which can help describe what happens in mental health services. However, despite identification of the issue a decade ago [13], there remains no consensus about ideal methods or measures of service content. Further research in the following areas could help to establish such a consensus:

-

The development of measures which provide greater depth of information about the nature of care provided at services, especially inpatient services.

-

More testing of the psychometric properties of measures across a range of service settings.

-

More investigation of the feasibility of measures in different service settings, including routine reporting of completion rates in use of process measures in studies.

-

The development of measures which include patients’ perspective on the content of care at services.

In the absence of established ideal methods and gold standard measures, current measurement of the content of care in mental health services should use a multi-methods approach. Data from a variety of information sources and collection methods can maximise the breadth and depth of information available and, if consistent, increase confidence in its validity. Focus on the nature of interventions provided by services, not just their number or the type of service within which they are provided, can aid description and distinction of mental health services and the goal of understanding service outcomes.

References

Abramowitz S, Obten N, Cohen H (1998) Measuring HIV/AIDS Case Management. Soc Work Healthcare 27(3):1–28

Beecham J, Knapp M (1992) Costing psychiatric interventions. In: Thornicroft G, Brewin CWJ (eds) Measuring mental health needs, Gaskell, pp 163–183

Bond G, Salyers M (2004) Prediction of outcome from the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment fidelity Scale. CNS-Spectrums 9(12):937–942

Bowers L, Brennan G, Flood C, Lipang M, Oladapo P (2006) Preliminary outcomes of a trial to reduce conflict and containment on acute psychiatric wards: City Nurses. J Psychiatr Mental Health Nursing 13:165–172

Bowie P, Mountain G (1993) Using direct observation to record the behaviour of long-stay patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 8:857–864

Brekke J (1987) The model-guided method for monitoring program implementation. Eval Rev 11(3):281–299

Brekke J, Long J (1997) The impact of service characteristics on functional outcomes from Community Support Programs for persons with schizophrenia: a growth curve analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 65(3):464–475

Brekke J, Ansel J, Long J, Slade E, Weinstein M (1999) Intensity and continuity of services and functional outcomes in the rehabilitation of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Services 50(2):248–256

Brugha T, Glover G (1998) Process and health outcomes: need for clarity in systematic reviews of case management for severe mental disorders. Health Trends 30(3):76–79

Brugha TS, Lindsay F (1996) Quality of mental health service care: the forgotten pathway from process to outcome. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 31(2):89–98

Bryman A (2004) Social research methods, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press

Burns T, Fiander M, Kent A, Ukoumunne OC, Byford S, Fahy T, Kumar KR (2000) Effects of case-load size on the process of care of patients with severe psychotic illness. Report from the UK700 trial. Br J Psychiatry 177:427–433

Burns T, Priebe S (1996) Mental health care systems and their characteristics: A proposal. Acta Psychiatr Scand 94(6):381–385

Dean R, Proudfoot R (1993) The Quality of Interactions Schedule (QUIS): Development, Reliability and Use in the Evaluation of Two Domus Units. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 8:819–826

De Jong A (2000) Development of the International Classification of Mental Health Care (ICMHC). Acta Psychiatr Scand 102(Suppl 405):8–13

De Jong A, Giel R, Tentlom G (1991) International classification of mental health care: a tool for classifying services providing mental health care Part 1. Dept Social Psychiatry, University of Groningen and World Health organisation Regional office for Europe, Groningen

Dietzen L, Bond G (1993) Relationship between case manager contact and outcome for frequently hospitalised psychiatric clients. Hospital Community Psychiatry 44(9):839–843

Donabedian A (1980) Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring, Volume 1: the Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment Health Administration Press

Falloon I, Fadden G (1995) Integrated mental health care: a comprehensive community-based approach Cambridge University Press

Fiander M, Burns T (2000) A Delphi approach to describing service models of community mental health practice. Psychiatr Serv 51(5):656–658

Fisher G, Landis D, Clark D (1988) Case management service provision and client change. Commun Mental Health J 24(2):134–142

Glick I, Burti L, Suzuki K, Sacks M (1991) Effectiveness in psychiatric care: 1. A cross-national study of the process of treatment and outcomes of major depressive disorder. J Nerv Mental Disease 179(2):55–63

Hansson KS, Allebeck P, Malm U (2001) Event recording in psychiatric care: Developing an instrument and 1-year results. J Nordic Psychiatry 55(1):25–31

Higgins R, Hurst K, Wistow G (1999) Nursing acute psychiatric patients: a quantitative and qualitative study. J Advanced Nursing 29(1):52–63

Johnson S, Salvador-Carulla L (1998) Description and classification of mental health services: a European perspective. European Psychiatry 13:333–341

Johnson S, Kuhlman R (2000) The EPCAT Group, “The European Service Mapping Schedule (ESMS): development of an instrument for the description and classification of mental health services”. Acta Psychiatr Scand 102:14–23

Kitwood T (1997) Evaluating dementia care: the DCM method, 7th edn. Universwity of Bradford

Kovess V, Lafleche M (1988) How do teams practice community psychiatry?”. Canada’s Mental Health 36(2):1–28

McGrew J, Bond G, Dietzen L, Salyers M (1994) Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program model. J Consult Clin Psychol 62:670–678

McHugo G, Drake R, Teague G, Xie H (1999) Fidelity to assertive community treatment and client outcomes in the new hampshire dual disorders study. Psychiatr Service 50(6):818–824

Mechanic D (1996) Emerging issues in international mental health services research. Psychiatr Services 47(4):371–375

Morley S, Snaith P (1992) Principles of psychological assessment. In: Freeman C, Tyrer P (eds) Research methods in psychiatry, 2nd edn. Gaskell, pp 135–152

Morse G, Calsyn R, Klinkenberg W, Helminiak T, Wolff N, Drake R, Yonker R, Lama G, Lemming M, McCudden S (2006) Treating homeless clients with severe mental illness and substance use disorders: costs and outcomes. Commun Mental Health J 42(4):377–404

Olusina AK, Ohaeri JU, Olatawura MO (2003) The quality of interactions between staff and psychiatric inpatients in a Nigerian general hospital. Psychopathology 36(5):269–275

Patmore C, Weaver T (1989) A measure of care. Health Serv J 99(5142):330–331

Paul G (1987) Rational operations in residential treatment settings through ongoing assessment of staff and client functioning. In: Peterson D, Fishman D (eds) Assessment for decision, Rutgers University Press, pp 145–203

Pawson R, Tilley N (1997) Realistic Evaluation. Sage

Popkin M, Callies A, Lurie N, Harman J, Stoner T, Manning W (1997) An instrument to evaluate the process of care in ambulatory settings. Psychiatr Service 48(4):524–527

Quirk A, Lelliot P (2001) What do we know about life on acute psychiatric wards in the UK? A review of the research evidence. Soc Sci Med 53(12):1565–1574

Resnick S, Neale M, Rosenheck R (2003) Impact of Public Support Payments, intensive pychiatric community care and program fidelity on employment outcomes for people with severe mental illness. J Nerv Mental Disease 191(3):139–144

Rossberg J, Friis S (2004) Patients’ and staff’s perceptions of the psychiatric ward environment. Psychiatr Service 55(7):798–803

Rossi P, Freeman H (1989) Evaluation: a systematic approach, 4th edn. Sage

Rossi P, Freeman H, Lipsey G (1999) Evaluation: a systematic approach, 6th edn. Sage

Salize HJ, Kustner BM, Torres-Gonzalez F, Reinhard I, Estevez JFJ, Rossler W (1999) Needs for care and effectiveness of mental health care provision for schizophrenic patients in two European regions: a comparison between Granada (Spain) and Mannheim (Germany). Acta Psychiatr Scand 100(5):328–334

Shepherd G, Richardson R (1979) Organization and interaction in psychiatric day centers. Psychol Med 9:573–579

Slade M, Phelan M, Thornicroft G (1998) A comparison of needs assessed by staff and by and epidemiologically representative sample of patients with psychosis. Psychol Med 28(3):543–550

Slade M, Thornicroft G, Loftus S, Phelan M, Wykes T (1999) The camberwell assessment of need Gaskell, London

Teague G, Bond G, Drake R (1998) Programme fidelity in ACT: development and use of a measure. Am J Orthopsychiatry 68:216–232

Thornicroft G, Tansella M (1999) The mental health matrix: a Manual to Improve Services Cambridge University Press

Thornton A, Hatton A, Tatham A (2004) Dementia care mapping reconsidered: exploring the reliability and validity of the observational tool. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19:718–726

Tugwell P (1979) A methodological perspective on process measures of the quality of medical care. Clin Investigat Med 2:113–121

Tyson G, Lambert G, Beattie L (1995) The quality of psychiatric nurses’ interactions with patients: an observational study. Int J Nursing Studies 32(1):49–58

Whitley R, Crawford M (2005) Qualitative research in psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry 50(2):108–114

Wing J, Brown G (1970) Institutionalism and Schizophrenia Cambridge University Press

Wright R, Sklebar T, Heiman J (1987) Patterns of case management activity in an intensive community support programme. Commun Mental Health J 23(1):53–59

Young A, Sullivan G, Burnam A, Brook R (1998) Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:611–617

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lloyd-Evans, B., Johnson, S. & Slade, M. Assessing the content of mental health services: a review of measures. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 42, 673–682 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0216-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0216-x