Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown an elevated risk with regard to social and behavioural domains in adolescents of single parents. However, the diversity of single parent families concerning gender of the resident parent has seldom been taken into account when investigating the relation between family structure and children’s negative outcomes. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate risk behaviours, victimisation and mental distress among adolescents in different family structures using more detailed sub-groups of single parents (i.e., single mother, single father and shared physical custody).

Methods

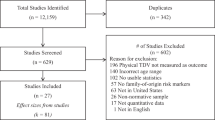

The sample consisted of 15,428 ninth graders from all municipal and private schools in the county of Stockholm (response rate 83.4%). Risk behaviours included use of alcohol, illicit drugs and smoking. Victimisation was measured by experiences of exposure to bullying and physical violence. Mental distress was assessed with the anxious/depressed and aggressive behaviour syndrome scales in the Youth Self Report (YSR). Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to investigate the associations between family structure and outcome variables.

Results

Adolescents in single-mother/father families were at higher risk of risk behaviours, victimisation and mental distress than their counterparts in two-parent families. However, after control for possible confounders the associations between victimisation, aggressive behaviour problems and single motherhood were no longer significant, whereas these relations remained for children living with single fathers. Adolescents in shared physical custody run no increased risk of any of the studied outcomes (except drunkenness) after adjustment for covariates. Post hoc analyses revealed that adolescents in single-father families were at higher risk for use of alcohol, illicit drugs, drunkenness, and aggressive behaviour as compared to their peers in single-mother families, whereas no differences were found between adolescents in single-mother families and those in shared physical custody.

Conclusions

Children of single parents should not be treated as a homogenous group when planning prevention and intervention programmes. Researchers and professionals should be aware of and consider the specific problems of single parent children and that their problems may vary depending on their living arrangements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research on the impact of family structure on children’s outcome indicates that growing up in a single parent family is associated with higher risk for substance abuse, adjustment problems, emotional problems and delinquent behaviour [3, 6, 20, 23, 28, 34, 43, 49]. However, there seems to be a lack of consistency in the literature regarding the extent to which lone parenthood in itself is an unfavourable form of family structure for children’s development. While some studies show that lone parenthood per se is detrimental to children’s outcomes [16, 19, 37], thus suggesting that the absence of one parent may influence the children negatively, others have failed to observe such an association when effects of situations closely associated with single parent households were taken into account [18, 29, 40]. For example, low social and financial status of the household, mental and/or physical ill-health of the parent are known correlates of children’s negative outcomes, but are also factors where single parents are overrepresented [9, 41, 48].

Experiences of socio-economic hardship and/or ill-health of the resident parent are also recognized as factors closely related with the quality of parenting [42]. According to Wallerstein and Kelly (1980) “diminished parenting” may express itself in distant, authoritarian attitudes toward the child, low emotional availability and unsupervision [59]. Such parenting practices are in turn recognised to be greatly influential in predicting the child’s well-being and development [42, 52].

Another factor warranting attention is experience of family dissolution. A great majority of children living with a single parent have experiences of family dissolution that in many cases were preceded by a high level of conflict between the two parents. Witnessing marital conflicts appears, probably by modelling aggressive behaviour, to be particularly important for children’s psychological well-being and behaviour. After family dissolution the problem of frequent transitions in the family structure represents yet another factor that may be unbeneficial for the well-being of the child [32]. Thus, considering all the obstacles for gainful development that some children in single parent families have to cope with, the problems they express should be regarded as an adequate rather than deviant behaviour.

Sweden, like many other European countries, has over the past decades experienced an increase in lone parent families. According to the Swedish Bureau of Statistics’ census data in 2004, 25% of children up to 17 years lived in lone parent families, compared with nearly 13% 20 years ago [53]. However, although lone mothers constitute the majority of single parents, recent estimates indicate that the number of single-father families and shared physical custody arrangements is increasing and accounts in the county of Stockholm for about 4 and 5% respectively [55]. Therefore, a dichotomous distinction between single-parent versus two-parent families, as has been used in some studies, is too simplistic.

Despite the fact that lone families are not homogenous concerning, among other things, gender of the resident parent, the majority of findings pertaining to child adjustment and family structure rely on data that are drawn from samples of children resident with their mothers. Children of lone fathers and children with dual residence have often been excluded from the study’s design. On the other hand, existing findings where diversity of family structure has been taken into account are rather contradictory. While some studies have found that children in lone father families reported more problems with regard to social and behavioural domains when compared to their counterparts in either lone mother families or shared physical arrangements [6, 7, 27, 28], others have observed no such differences [26, 47]. In contrast, McMunn et al. (2001) found that children of lone fathers, as opposed to those of lone mothers, were not at higher risk for emotional and behavioural problems compared to children in two-parent families. However, the association between lone motherhood and negative outcome disappeared when socio-economic factors were taken into consideration.

With regard to the effects of shared physical custody the results are also inconsistent. It is suggested that children in this kind of living arrangement and children of lone parents are equally well adjusted [25, 30]. However, other researchers have found that shared physical custody appears to be superior to one parent custody with respect to child adjustment [5, 8, 21, 45, 51]. This living arrangement is often associated with advantages such as maximized father involvement in parenting, as well as task and response sharing between parents [30].

In summary, the literature suggests that studies covering more detailed sub-groups of lone parenting are warranted when investigating if children living in non-intact families differ in terms of their adjustment problems from their counterparts in two-parent families. The aim of this study was to overcome this limitation by focusing on the diversity among single-parent families. We also account for the influence of factors beyond the family structure (e.g., gender, length of residence in Sweden, number of close friends, ability to make friendships, school satisfaction and truancy) that may have an influential role in the outcomes.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 15,428 ninth graders from all municipal and private schools, in the county of Stockholm. Of the contacted students, 12,860 (83.4%) in 697 classes participated in the study. We excluded 162 students because they did not answer the question about their living arrangements. In addition, 116 foster children/children living with guardians were also excluded. Thus, the studied sample consisted of 12,582 children. The proportions of adolescent in different family structures were as follows: 68.5% living in a two-parent family, 23.2% in a single-mother family, 4.8% in a single-father family, and 3.5% in shared physical custody.

Measures

Dependent variables

Risk behaviours included use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and smoking. The alcohol measure included the substantial consumption of alcohol (i.e., at least 2.5 dl alcohol on the same occasion) and experience of drunkenness. Illicit drug use was measured by asking whether the student had ever used any illicit substance (e.g., marijuana, amphetamine). Smoking was measured by asking students whether they have ever smoked with responses varying from “never” to “regular use”. Individuals who answered “every/almost every day” and “at the weekends” were defined as smokers.

Victimisation included experiences of exposure to bullying and physical violence. Bullying was measured by the following question: “Have you ever been bullied during the past school year?” Physical violence was measured by the question: “During this school year have you ever been hit or kicked by someone so seriously that you needed to visit a doctor, dentist or nurse?”

Mental distress was assessed with the anxious/depressed and aggressive behaviour syndrome scales in the Youth Self Report (YSR) [1]. The two syndrome scales contain 35 questions. An adolescent selects his or her response from 0 (not true) to 2 (Very true or often true). The 90th percentile cut-off levels were used to identify the presence of each of the behaviours. This cut-off point was chosen on the basis of a previous Swedish study [36] showing that the both scales had as good psychometric properties for assessing mental distress in the non-clinical sample of adolescents as the total Internalizing and Externalizing problems scales, for which the clinical ranges start at the 90th percentiles [1].

Independent variables

Family structure was determined by asking the question: “Do you live together with your mother and father?” and was followed by seven response options: (1) yes, together with both; (2) no, I live only with my mother; (3) no, I live only with my father; (4) I live most of the time with my mother, sometimes with my father; (5) I live an equal amount of time with each of my parents; (6) I live most of the time with my father, sometimes with my mother; (7) I live neither with my mother nor with my father, I live …. . The alternatives were further grouped into the following four categories of family structure: (a) intact family (answer alt. 1); (b) single-mother family (answer alt. 2 and 4); (c) single-father family (answer alt. 3 and 6); (d) shared physical custody (answer alt. 5). Children who chose the seventh alternative were defined as foster children/children living with guardians and thus excluded from the current study.

Other independent variables used in this study were: gender, length of residency in Sweden, number of close friends, ability to make friends, school satisfaction and truancy. Length of residency was measured by asking respondents to specify the number of years that they had lived in Sweden. Response categories ranged from “my entire life” to “less than 5 years”. Participants who chose other category than the first one were considered to be of foreign background.

Participants were also asked about the number of close friends (five response options ranged from “none” to “six or more”), their ability to make friends (five response options ranged from “very good” to “very poor”), whether they were satisfied with the school (five response options ranged from “very satisfied “to “very poorly satisfied”), and whether they played truant (six response options ranged from “never” to “several times a week”). For the analyses all answer alternatives (except truancy habits) were trichotomized as indicated in Table 1. Truancy was dichotomised into “less than two times per month” and “two times per month or more often”.

The rationale of using these variables was their possible confounding influence on the associations between family structure and outcomes [10, 14, 24, 31, 35, 57]. As we were not aware of the possible influence of foreign background on the associations between family structure and outcomes, separate analyses examining correlations between foreign background and outcome variables (not shown) were performed. Since all these relationships were significant (children living in Sweden their entire life were overrepresented in groups reporting substantial use of alcohol and drunkenness, whereas the opposite was true concerning use of any illicit substance, victimisation and aggressive behaviour problems) foreign background was included in the analyses.

Design and procedure

The data for the present study were obtained as a part of the CAN (Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and other Drugs) comprehensive investigation of substance use among primary school children. The questionnaire with a total of 88 questions was sent to all ninth graders in Stockholm’s county. Participants were asked to respond to the questionnaire during a lesson in school. Anonymity was emphasised.

Statistical analyses

Differences in the independent variables between children living in various family structures were tested using chi-square. The bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used in order to investigate the associations between family structure and outcome variables. Multivariate analyses were adjusted for the following covariates: gender, length of residency in Sweden, number of close friends, ability to make friendships, school satisfaction and truancy. Crude and adjusted odds ratios were determined. Owing to the large number of participants, and the large number of comparisons, the significance level was set at 0.01.

Results

Demographic variables, school satisfaction, truancy, number of close friends and ability to make friends

Results of chi-square analyses revealed that living in a single-father family was more frequent among male adolescents than among their female counterparts (5.7% vs. 3.9%), whereas the opposite was true for living in a singe mother family (21.3% vs. 25.1%) [χ2(3) = 43.6, p < .0001]. A shared physical custody arrangement was more common among adolescents who had lived in Sweden their entire life than among those who had not (3.9% vs. 0.9%) [χ2(3) = 39.5, p < .0001].

As shown in Table 1, adolescents in two-parent families reported less frequently low/very low school satisfaction and truancy than those in non-intact families. Compared to other groups, adolescents in two-parent or single-mother families reported more often having no friends. In addition, adolescents in single-mother families were overrepresented among those having difficulties in making friends.

Risk behaviours

As shown in Table 2, adolescents in non-intact families (i.e., single-mother/single father and shared physical custody) were at higher risk for use of alcohol, illicit drugs, drunkenness and smoking than their counterparts in intact families. After adjusting for covariates, these differences remained for adolescents in single-mother/single-father families. In addition, adolescents in shared physical custody were at higher risk of drunkenness as than youths in two-parent families.

Victimisation

As shown in Table 3, adolescents in single-mother/single-father families were at higher risk of being victims of bullying/physical violence than adolescents in two-parent families. After control for covariates, the association between victimisation and coming from a single-mother family was no longer significant.

Mental distress

As shown in Table 4, adolescents in single-mother/single-father families were at higher risk of aggressive behaviour problems than their counterparts in two-parent families. After adjustment for covariates, higher risk for expressing aggressive behaviour problems remained significant only for adolescents in single-father families. Adolescents in single-mother families were at higher risk of anxiety/depressive problems. However, this association was no longer significant when covariates were taken into account.

Post hoc analyses

Post hoc regression analyses, performed to determine whether single-parent families differed from each other in terms of risks for the studied outcomes, revealed that adolescents in single-father families were at higher risk for use of alcohol (OR = 1.3, p < 0.01), illicit drugs (OR = 1.4, p < .0.01), drunkenness (OR = 1.4, p < 0.001), and aggressive behaviour (OR = 1.4, p < 0.01) as compared to their counterparts in single-mother families. Although not statistically significant (p-value varied between 0.02 and 0.07), there were tendencies to suggest that adolescents in single-father families might be at higher risk for use of illicit drugs, drunkenness and physical victimisation than adolescents in shared physical custody. There were no differences in outcomes between adolescents in single-mother families and shared physical custody (results not shown in the table format).

Discussion

Overall, the results of this study seem to be in line with research indicating that children of single parents do not constitute a homogenous population in terms of different aspects of their psychosocial functioning [28, 44]. Consistent with prior research, children of single mothers/fathers were at higher risk of various behavioural problems than children in two-parent families [6, 23, 28, 34, 43]. However, after control for possible confounders the associations between victimisation, aggressive behaviour problems and single motherhood were no longer significant, whereas these relations remained for children living with single fathers. From our data one could speculate that, since children of single mothers more often reported having no friends and having difficulties in making friends than children in other groups, the bivariate associations between this living arrangement and victimization/aggressive behaviour problems may, at least to some degree, be mediated through problems with social networks. However, further research is needed to support this hypothesis.

The current study indicates that although children of single parents fared worse regarding risk behaviours, victimisation and mental distress than children in intact families, children of single fathers fared even worse than those of single mothers. Several arguments can be offered to explain why children of single parents may be more likely to have poorer psychological and/or social adjustment. First, research shows that single and two-parent households differ, to the disadvantage of the former, in standard of living [53], parental health and well-being [48], amount and quality of parental support [22], and monitoring [17, 56]. All these factors have been recognized as contributing to the development and well-being of children [12, 17]. Second, it has been argued that the non-resident parent’s degree of involvement in the child’s life appears to be influential on psychological and behavioural outcomes [4]. Third, the majority of children in single households have experiences of divorce/separation of their parents. Such experiences and parental conflicts preceding separation have been reported as a stressful life transition for most of the children, with psychosocial repercussions evident even long after family breakdown [2, 33].

Studies concerning children of single fathers are scarce and yield mixed results. Whereas some authors have found that children of single fathers manifest more psychosocial problems than children of single mothers [6, 7, 12, 27, 39, 44], others have not observed such a difference [40] or found the opposite result [11]. These inconsistent findings may be, at least partly, attributable to the differences in design of the studies and sample characteristics. For example, while the parent was the informant in the study of McMunn and colleagues, our results rely on self-reports of children. Since some authors have found parents to underestimate the extent of the problem behaviours experienced by their children [50, 58], children’s self-reports may be a more valid source of information.

A number of factors, beyond the scope of the current study to investigate, may have contributed to the present results concerning single-father families. For example, our findings may be a reflection of a lower degree of monitoring and control over leisure activities provided by single fathers as compared with single mothers [7, 12, 15]. Poor parental monitoring is likely to lead to increased frequency of antisocial behaviours (e.g., substance use) [12, 13]. Another explanation based on prior findings could be that children of single fathers tend to experience more family transitions [8] that in turn augment the risk of negative outcomes [46]. It should be underlined, however, that as the effects of growing up in single-father family are still a relatively new area of research, future studies are needed to verify and explore this issue.

The bivariate analysis of the associations between family structure and smoking, illicit substances, alcohol consumption, and drunkenness showed that children in shared physical custody were more likely to participate in these activities than those from two-parent families. However, in contrast to children living solely with mothers or fathers, these associations (except drunkenness) were no longer significant when other factors were taken into consideration. Children in shared physical custody run no increased risk of victimisation or mental distress. Thus, these results seem to be in concert with previous studies that found shared physical custody to be superior to the other forms of single-parent households with respect to the children’s well-being and different forms of adjustment [5, 8]. What makes dual residence better than other living arrangements of children of single parents is not fully investigated. The growing body of research suggests that parents choosing shared physical custody often have a lower level of conflict with each other, a more cooperative relationship, and are better off financially compared to other single parents [5, 53]. All these circumstances may be of importance to the development and well-being of children. Furthermore, some studies indicate that shared physical custody may have a beneficial influence on parental health [26, 40] that in turn presumably leads to the provision of better care for the child. However, the post hoc analyses failed to show any significant differences between shared physical custody and single-mother families, indicating that when compared to each other, groups were similar with respect to the studied outcomes. In addition, although post hoc analyses suggested that shared physical custody may be more to the advantage of the adolescents than the single-father family, this finding should be interpreted cautiously in light of its statistical tendencies.

Although the current study provides some important insights regarding present knowledge about residence arrangements and psychosocial functioning of children its shortcomings must be acknowledged. First, the cross sectional design of the study does not provide conclusive evidence of causation. Another study design is required (e.g., longitudinal) to determine whether residence arrangements have protective/risk-enhancing effects on children’s psychosocial functioning. Second, it was not possible to determine to what extent non-intact mother-/father-headed families contained parents currently married/cohabiting, and thus not constituting single-parent households. However, since our figures concerning the percentages of single-mother/father families are comparable (slightly lower) with those presented by Statistics Sweden for the year 2000 [54], it could be assumed that for the majority, the label “single parent” was sufficient. Finally, not taking into account the role of economic conditions and parental mental/physical health as possible confounders between residence arrangements and outcomes is an obvious limitation. However, since financial strain seems not to constitute the primary source of concern for single-father families, there is little reason to believe that inclusion of economic variables would markedly weaken the results found for paternal living arrangements. Despite these limitations, the reliability of the study is to some extent confirmed by the fact that in many respects results are consistent with previous findings in the field.

Conclusions

Our study confirmed that children of single mothers/fathers run an increased risk of poor psychosocial functioning compared to children in two-parent families. These differences persisted in the presence of such control variables as gender, length of residence in Sweden, number of close friends, ability to make friends, school satisfaction and truancy. However, the increased risk for victimisation and aggressive behaviour problems among children in lone mother families was no longer apparent when control variables were included. Moreover, when compared directly, single mother and single father families differed, to the disadvantage of the later, in use of alcohol, illicit drugs, drunkenness, and aggressive behaviour. These findings suggest that children of single parents should not be treated as a homogenous group when planning prevention and intervention programmes. Researchers and professionals should be aware of and consider the specific problems of single-parent children that apparently may vary depending on their living arrangements. In view of the fact that risk behaviours and aggressive behaviour problems during adolescence have been strongly linked to serious delinquent behaviours later in life [38], focusing on the needs of children in single-parent households, particularly children of single fathers, seems to be essential in preventing problem behaviours affecting not only a single individual but also society as a whole. As a relatively recent phenomenon, single fatherhood may also be associated with specific experiences and needs of the fathers that are not fully recognized in research and practice. Thus, in order to develop programmes that effectively meet the requirements of single-parent families, future studies should acknowledge if and in what way single mothers and single fathers face different challenges in their parenting role.

Our findings indicate that shared physical custody was to a lesser extent than other non-traditional family structures associated with poor psychosocial functioning of children. However, when compared directly to other non-intact families shared physical custody did not emerged as a living arrangement at significantly lower risk for any of the outcomes studied. Differences concerning, use of illicit drugs, drunkenness and physical victimisation observed between adolescents in shared physical custody and their counterparts in single-father families, although not statistically significant, may indicate some superiority of the former family structure. However, as these analyses were not planned a priori the results must be regarded as exploratory. Further research is needed on this subject.

References

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for the youth self-report and profile. Burlington, University of Vermont

Amato PR (2000) The consequences of divorce for adults and children. J Marriage Fam 62:1269–1288

Amato PR, Keith B (1991) Parental divorce and the well-being of children: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 110:26–46

Amato PR, Gilbreth JG (1999) Non-resident fathers and children’s wellbeing: A meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam 61:557–573

Bauserman R (2002) Child adjustment in joint-custody versus sole custody arrangements: a meta-analytic review. J Fam Psychol 16:91–102

Bjarnason T, Andersson B, Choquet M., Elekes Z, Morgan M, Rapinett G (2003) Alcohol culture, family structure and adolescent alcohol use: multilevel modeling of frequency of heavy drinking among 15–16 year old students in 11 European countries. J Stud Alcohol 64:200–208

Buchanan CM, Maccoby EE, Dornbusch SM (1992) Adolescents and their families after divorce: three residential arrangements compared. J Res Adolesc 2:261–291

Buchanan CM, Maccoby EE, Dornbusch SM (1996) Adolescents after divorce. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Burström B, Diderichsen F, Shouls S, Whitehead M (1999) Lone mothers in Sweden: trends in health and socioeconomic circumstances, 1979–1995. J Epidemiol Commun H 53:750–756

Chou LC, Ho CY, Chen CY, Chen WJ (2006) Truancy and illicit drug use among adolescents surveyed via street outreach. Addict Behav 31:149–154

Clarke-Stewart KA, Hayward C (1996) Advantages of father custody and contact for the psychological well-being of school age children. J Appl Dev Psychol 17:239–270

Cookston JT (1999) Parental supervision and family structure: effects on adolescent problem behaviors. J Divorce Remarriage 32:107–122

Curtner-Smith ME, MacKinnon-Lewis CE (1994) Family process effects on adolescent males’ susceptibility to antisocial peer pressure. Fam Relat 43:462–268

Demo DH, Acock AC (1988) The impact of divorce on children. J Marriage Fam 50:619–648

Demuth S, Brown SL (2004) Family structure, family processes, and adolescent delinquency: the significance of parental absence versus parental gender. J Res Crime Delinq 41:58–81

Dodge KA, Petit GS, Bates JE (1994) Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Dev 65:649–665

Dornbusch SM, Carlsmith JM, Bushwall SJ, Ritter PL, Leiderman H, Hastorf AH, Gross RT (1985) Single parents, extended households, and the control of adolescents. Child Dev 56:326–341

Dunn J, Deater-Deckard K, Pickering K, O’Connor TG (1998) Children’s adjustment and prosocial behaviour in step-, single-parent, and non-stepfamily settings: findings from a community study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 39:1083–1095

Flewelling R, Bauman K (1990) Family structure as a predictor of initial substance use and sexual intercourse in early adolescence. J Marriage Fam 52:171–181

Garnefski N, Diekstra RF (1997) Adolescents from one parent, stepparent and intact families: emotional problems and suicide attempts. J Adolesc 20:201–208

Glover RJ, Steele C (1989) Comparing the effects on the child of post-divorce parenting arrangements. J Divorce 12:185–201

Gore S, Aseltine RH, Colton ME (1992) Social structure, life stress, and depressive symptoms in a high school-aged population. J Health Soc Behav 33:97–113

Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Scheier LM, Diaz TL, Miller NL (2000) Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychol Addict Behav 14:174–184

Grych JH, Fincham FD (1992) Interventions for children of divorce: toward greater integration of research and action. Psychol Bull 111:434–454

Haddad T (1998) Custody arrangements and the development of emotional or behavioural problems in children. Ottawa: Human Resources Development Canada, Applied Research Branch

Hilton JM, Devall EL (1998) Comparison of parenting and children’s behavior in single-mother, single-father, and intact families. J Divorce Remarriage 29:23–54

Hoffman JP, Johnson RA (1998) A national portrait of family structure and adolescent drug use. J Marriage Fam 60:633–645

Jenkins JE, Zunguze ST (1998) The relationship of family structure to adolescent drug use, peer affiliation, and perception of peer acceptance of drug use. Adolescence 33:811–822

Joshi HE, Cooksey E, Wiggins RD, McCulloch A, Verropoulou G, Clarke L (1999) Diverse family living situations and child development: a multi-level analysis comparing longitudinal evidence from Britain and the United States. Int J Law Policy Fam 13:292–314

Kline M, Tschann JM, Johnston JR, Wallersttein JS (1989) Children’s adjustment in joint and sole physical custody families. Dev Psychol 25:430–438

Kohn L, Dramaix M, Favresse D, Kittel F, Piette D (2005) Trends in cannabis use and its determinants among teenagers in the French-speaking community of Belgium. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 53:3–13

Kurdek LA, Fine MA, Sinclair RJ (1995) School adjustment in sixth graders: parenting transitions, family climate, and peer norm effects. Child Dev 66:430–445

Laumann-Billings L, Emery RE (2000) Distress among young adults in divorced families. J Fam Psychol 14:671–687

Ledoux S, Miller P, Choquet M, Plant M (2002) Family structure, parent–child relationships, and alcohol and other drug use among teenagers in France and the United Kingdom. Alcohol 37:52–60

Licanin I, Redzic A (2005) Alcohol abuse and risk behavior among adolescents in larger cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Med Arh 59:164–167

Lindberg L, Larsson N, Bremberg S (1999) Ungdomars psykiska hälsa. Utvärdering av ett mätinstrument. Samhällsmedicin, Huddinge (in Swedish)

Lipman EL, Offord DR, Dooley MD (1996) What do we know about children from single-mother families? Questions and answers from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. I Growing Up in Canada: National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. Ottawa, Statistics Canada

Lipsey MW, Derzon JH (1998) Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescences and early adulthood. In: Loeber IR, Farrington DP (eds) Serious and violent juvenile offenders. Risk factors and successful interventions. Sage, London

Luoma I, Puura K, Tamminen T, Kaukonen P, Piha J, Rasanen E, Kumpulainen K, Moilanen I, Koivisto AM, Almqvist F (1999) Emotional and behavioural symptoms in 8–9-year-old children in relation to family structure. Eur Child Adoles Psy 8:29–40

McMunn AM, Nazrooa JY, Marmota MG, Borehamb R, Goodmanc R (2001) Children’s emotional and behavioural well-being and the family environment: findings from the Health Survey for England. Soc Sci Med 53:423–440

McLanahan SS (1999) Father absence and children’s welfare. In: Hetherington EM (ed) Coping with divorce, single parenting, and remarriage: a risk and resiliency perspective. Erlbaum, Mahway, NJ

McLanahan SS, Sandefur G (1994) Growing up with a single parent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Miller PM (1997) Family structure, personality, drinking, smoking and illicit drug use: a study of UK teenagers. Drug Alcohol Depen 45:121–129

Naevdal F, Thuen F (2004) Residence arrangements and well-being: a study of Norwegian adolescents. Scand J Psychol 45:363–371

Neugebauer R (1989) Divorce, custody, and visitation: the child’s point of view. J Divorce 12:153–168

Peterson JL, Zill N (1986) Marital disruption, parent–child relationships, and behavior problems in children. J Marriage Fam 48:295–307

Pike L (2000) Single mum or single dad? The effects of parent residency arrangements on the development of primary school-aged children. Western Australia, Edith Cowen University

Ringbäck Weitoft GR, Haglund B, Hjern A, Rosen M (2002) Mortality, severe morbidity and injury among long-term lone mothers in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol 31:573–580

Ringbäck Weitoft G, Hjern A, Haglund B, Rosen M (2003) Mortality, severe morbidity, and injury in children living with single parents in Sweden: a population based study. Lancet 361:289–295

Seiffge-Krenke I, Kollmar F (1998) Discrepancies between mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of sons’ and daughters’ problem behaviour: a longitudinal analysis of parent-adolescent agreement on internalising and externalising problem behavior. J Child Psychol Psy 39:687–697

Shiller V (1986) Joint versus maternal custody for families with latency age boys: parent characteristics and child adjustment. Am J Orthopsychiatry 56:486–489

Simons RL, Lin K, Gordon LC, Conger RD, Lorenz FO (1999) Explaining the higher incidence of adjustment problems among children of divorce compared with those in two-parent families. J Marriage Fam 61:1020–1033

Statistics Sweden 2005. Demographic reports 2005:2. Children and their families 2004. SCB-Tryck, Örebro. (in Swedish)

The Office of Regional Planning and Urban Transportation (2002) Barn och deras familjer i Stockholms län år 2000. En statistisk studie av barnen och deras levnadsförhållanden. SCB-Tryck, Örebro (in Swedish)

The Office of Regional Planning and Urban Transportation (2003) Barn och deras familjer i Stockholms län år 2003. En statistisk studie av barnen och deras levnadsförhållanden. SCB-Tryck, Örebro. (in Swedish)

Thomson E, McLanahan SS, Curtin RB (1992) Family structure, gender, and parental socialization. J Marriage Fam 54:368–378

Tomori M, Zalar B, Kores Plesnicar B, Ziherl S, Stergar E (2001) Smoking in relation to psychosocial risk factors in adolescents. Eur Child Adoles Psy 10:143–150

Verhulst FC, van der Ende J (1992) Agreement between parents’ reports and adolescents’ self-reports of problem behavior. J Child Psychol Psy 33:1011–1023

Wallerstein JS, Kelly JB (1980) Surviving the break-up: how children and parents cope with divorce. New York, Basic Books

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jablonska, B., Lindberg, L. Risk behaviours, victimisation and mental distress among adolescents in different family structures. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 42, 656–663 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0210-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0210-3