Abstract

Trust, choice and empowerment of patients are emerging as important issues in mental health care. This may be due to an increasingly consumerist attitude amongst patients and as a consequence of postmodern cultural changes in society. This study aimed to find evidence for the influence of trust, patient choice and patient empowerment in mental health care. A literature review was undertaken. Six searches of PubMed were made using the key terms trust, patient choice and power combined separately with psychiatry and mental health. The literature search found substantial research evidence in the areas of trust, choice and power including validated scales measuring these concepts and evidence that they are important to patients. Trust in general health clinicians was found to be high and continuity of care increases patients’ trust in their clinician. However, only qualitative research has been found on trust in mental health settings and further quantitative studies are needed. Patient choice is important to patients and improves engagement with services, although studies on outcome show varying results. Empowerment has impacted more at an organisational level than on individual care. Innovative research methodologies are needed to expand on the present significant body of research, utilising qualitative and quantitative techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Modern medical practice is a multifaceted task. Medical treatments have become increasingly technologically complex and there is an expectation that they are justified by scientific evidence. However, neither clinicians nor patients have forgotten the importance of a more traditional part of medical practice—the relationship between clinicians and patients. In this relationship three concepts are being increasingly examined—trust between clinicians and patients, giving patients more choice in their medical treatment and the empowerment of patients. These issues are relevant for the whole of medicine, none more so than mental health. The relationship between psychiatrists and patients is vital because psychotherapies are an integral part of treatment, the therapeutic relationship can predict long-term outcome [1], and because power differentials can be exacerbated by the possibility of compulsory assessment and treatment for the mentally ill.

Trust, choice and power may be emerging as important areas of research for several reasons. The political and social phenomena of consumerism and market economics are impacting on health. Patients may approach health care from a consumerist approach in which they expect to have more of a say in their treatment, and governments are looking for competition between service providers to improve quality of care and, perhaps, to reduce costs. This has led to a movement away from a more paternalistic relationship between doctors and patients towards giving patients more autonomy in the therapeutic relationship. There is an increased emphasis on identifying patient wishes in their health care. The availability of information on the internet has increased patient knowledge and changes in the financing of health care may lead to patients having more financial involvement in their care.

We also feel that these issues are fuelled by postmodern cultural changes in society. Postmodern criticisms of a scientific worldview [2, 3] have grown throughout the twentieth century and have impacted on medicine [4]. In mental health, a scientific model has been criticised as emphasising the biological aspects of illness over the psychological and social factors, as the former are easier to measure and therefore establish a clear evidence base [5]. A holistic view of experience has been elusive, as it is easier to measure reductionist models of human experience.

The scientific method used in mental health emphasises knowledge gained through controlled observation and measurement. The professionals who gain this knowledge are given the power to influence services through evidence-based medicine. However the objectivity of these professionals has been questioned, as commercial interests (through the pharmaceutical industry) and the importance of academic authority can both influence objective judgement [6]. Therefore, knowledge, power and trustworthiness of clinicians are issues thrown up by postmodern criticisms of scientific psychiatry. If the power of clinicians to determine services is questioned, the logical next step is to give more power to patients to make treatment decisions, and hence patient choice enters the debate. Recent UK government documents often presume that patient choice is a good thing and patient empowerment is a reality that can improve care [7]. However, the evidence for these presumptions in mental health is not established.

Aims of the study

We sought to complete a literature review to address the following research questions. Is there a research base for the influence of trust between patients and mental health clinicians? What is the evidence for the importance of choice in mental health care? Has patient empowerment had an impact on mental health delivery?

Material and methods

For the literature review we aimed to examine trust, patient choice and power. We performed a computerised search of the PubMed database (1980–2005). The searches included the key terms trust, patient choice and power. These were combined with psychiatry and mental health in separate searches. Therefore a total number of six searches were made. Some titles were clearly not relevant to the study area. If the title of the paper suggested that the article might be relevant, for example to the issue of trust in clinicians in mental health, then the abstracts were reviewed for the content of the article. Then if the abstract described conceptual ideas, research or reviews of research in the areas of trust, choice and power from the perspective of the care of the severely mentally ill, a copy of the full article was read, interpreted and included in the review. Any relevant papers or books cited by papers not previously found were reviewed and included if judged to be relevant. In addition, two publications not indexed on Medline, the Journal of Mental Health and the Psychiatric Bulletin were hand searched. Trust and psychiatry identified 349 articles whilst trust and mental health identified 279 (with an overlap in articles). From these papers, those found in the hand search and citations from these articles, 29 abstracts were reviewed. A total of 21 papers were included in the final literature review on trust. Patient choice and psychiatry identified 227 articles and patient choice and mental health identified 241 articles (again with significant overlap). Forty-seven abstracts were reviewed and a total of 21 papers were included in the final literature review on patient choice. For power the corresponding figures were 449, 587, 45 and 28.

Results

Trust

There has been debate and concern that public trust in institutions as a whole has been declining [8] and some have suggested that this loss of trust has extended to health professionals. However, patients’ trust in their clinicians is recognised as vital to healthcare as it is the basis for a positive therapeutic relationship. Yet the notion of trust can be difficult to define and to investigate [9].

Connotation of trust

Numerous definitions of trust have been put forward, in both general and medical contexts [10]. The majority “stress the optimistic acceptance of a vulnerable situation in which the truster believes the trustee will care for the truster’s interests” [11, p. 615]. This care includes a belief in the trustworthiness of the intent of the clinician, often includes an emotional element as it is relational, and involves a feedback loop, where experience can reinforce trust or lead to a sense of betrayal.

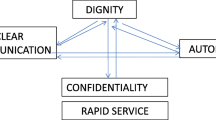

Trust can have multiple dimensions, summarized by Hall et al. [12] as follows:

-

1.

Fidelity. Pursuing the patient’s interests above the interests of other relevant parties.

-

2.

Competence. Avoiding mistakes and achieving the best possible outcomes, both technically and in areas of communication.

-

3.

Honesty. Telling the truth and avoiding falsehoods.

-

4.

Confidentiality. Protecting private information.

-

5.

Global trust. The holistic aspect of trust inherent to the relationship between people.

Trust is not only relevant to individual clinicians but is also relevant to how patients relate to institutions and larger health care systems in medicine. Patients will have relationships of trust in British mental health care with their individual psychiatrist, their local community mental health team, psychiatrists in general and NHS mental health services as a whole. These contrasting aspects of trust can interact. Whilst someone who trusts their personal clinician may as a consequence trust an institution more, faith in clinicians as a group will help a patient to trust a clinician he or she is meeting for the first time [13].

Measuring trust

At least four rating scales have been developed in medicine to measure trust in individual clinicians [12, 14 (Trust in Physician Scale), 15, 16]. There has been a scale to measure trust in the medical professional body as a whole [13] and other scales to measure trust in hospitals generally [17]. According to Hall et al. [12] all these scales have adequate psychometric properties and are broadly consistent with the dimensions of trust described above. Goudge and Gilson [9] observed that few of the scales used qualitative work to measure validity or reliability, instead relying on internal consistency and factor analysis. However, the Trust in Physician Scale has been shown to have adequate test–retest reliability and predicted some clinical outcomes, such as medication adherence [18] and the Wake Forest team [12, 13] described their method of trust scale development in detail. Scale development and empirical testing are more advanced for the scales for individuals than those for institutions. None have been specifically validated or used with mental health patients.

Evidence for trust

It is often thought that trust in the medical profession is waning [19]. However, studies examining trust in individual physicians does not bare this out. Using the Trust in Physician Scale, where 1 = strong distrust and 5 = strong trust, at least three studies show consistent average scores of 4 or more [12, 14, 18]. In contrast trust in institutions seems lower, although direct comparison is difficult as different concepts are involved [17, 20]. These studies used telephone interviews with the public or patients attending primary care in the USA.

A study interviewing primary care patients in both the USA and in the UK, using the Trust in Physician Scale, also showed high levels of trust in individual clinicians, similar in both countries [21]. The most significant factors associated with trust in the doctor were older age of patients and length of time of the relationship between patient and clinician. Gender, ethnicity, education, income levels and chronicity of illness were not associated with the strength of trust. The importance of continuity of care is supported by a US study [22]. However rather than the length of time of the relationship, the number of times the patient had seen the doctor was associated with increased trust, along with adequacy of choice and the degree of control in decision making. In another US study, Kao et al. [16] found the length of relationship and more choice of the physician was associated with greater trust.

We could find no quantitative studies on trust in mental health. A qualitative study in the UK, using in depth interviews, demonstrated that for 34 patients with an enduring mental illness, trust is important in building positive therapeutic relationships [23]. Emerging themes emphasised the importance of continuity of care in maintaining trust. Another UK study used focus groups of mental health service users to establish their views of services [24]. Service users felt a trusting clinician-user relationship was central to a good quality service.

Mechanic and Meyer [25] examined concepts of trust using qualitative interviews with three groups of patients—those with breast cancer, Lyme disease and mental illness in the US. Patients with mental illness stressed the importance of trusting the clinician to understand and minimize side effects of medication—this was more important to them compared to patients with the two physical diseases. Those with a mental illness also put more emphasis on the importance of confidentiality in trusting doctors, and also reported withholding information on substance misuse, dangerous behaviour and non-adherence to medication. The authors felt the mental health patients emphasized the importance of time with the clinician and the continuity of care with the same clinician.

One randomised controlled trial in the US attempted to teach family physicians to build and maintain trust with their patients using communication skill training [26]. The intervention group made no measurable difference in terms of patient trust, satisfaction and treatment adherence.

It is important to remember that the concept of trust should not be limited to patients but should include clinicians trust of their patients and, perhaps unique to psychiatrists who can treat patients against their will, the public’s trust of psychiatrists applying compulsory treatment. A study of the public’s attitudes to compulsory treatment of the mentally ill in Switzerland indicated a high level of trust in psychiatrists [27].

Choice

Connotations of choice in healthcare

The issue of choice in mental healthcare has become an important issue but has differing aspects. First, there are philosophical and ethical arguments for more patient choice. In the spectrum of patient involvement in care, at one end of the spectrum lies an attitude of paternalism, where the doctor knows what is best for the patient and decides treatment. At the other end of the spectrum is autonomy. Autonomy denotes the freedom from external control and right of self-determination. In healthcare an autonomous position suggests patients should have control over healthcare decisions. Another key ethical concept in patient choice is informed consent: a competent person has the right to refuse treatment.

Whilst over the last 20 years medical ethicists have stressed the importance of the principles of autonomy [28], the situation is complex. In emergency and life threatening situations, a paternalistic approach is more practically reasonable and perhaps desirable. In more elective procedures and situations where treatment decisions are more controversial, autonomy is argued for more. Mental health is unique to medicine in that some patients are treated against their will. Whilst this can be seen as the ultimate paternalistic position within medicine, most mental health patients are treated on a voluntary basis, and it may be possible to offer patients who are treated involuntarily some degree of autonomous choice in their treatment plan.

A second argument for patient choice is economic—the application of free market concepts to human services makes the case for more consumer choice in mental health care which may increase standards through competition between health care providers [29]. It is easy to confuse the two arguments for increased patient choice—philosophical and economic. For example the UK governments’ promotion of more patient choice focuses on patients having a choice between several hospitals competing to deliver a service for them, which follows an economic model but does not necessarily offer greater autonomy for the patient in their individualised treatment plan, as all the hospitals may all offer a paternalistic approach to care. On the other hand, increasing patient involvement in their individual treatment plan, for example through shared decision making, is seeking to offer greater autonomy for the patient, although actual choices for the patient may be extremely limited by resources. In summary, the term patient choice is used widely to debate philosophical and economic arguments for choice, and autonomy is just one of the philosophical concepts used to argue for more patient choice. This review focuses on the latter aspect—the autonomy of patient choice in their individual care.

In examining patient choice and the evidence for services in mental health, Salem [30] made the observation that in controlled trials patients are usually passive recipients of which service or treatment they receive. As such, these trials do not take into account how patient preference may influence how effective services might be in real life settings. Self-help groups and consumer run services for people with severe mental illnesses have been criticised as being self-selective, but rather than a weakness this may be a strength in emphasising that patients should be able to select the treatment they want.

In focussing on patient involvement in care, it is important to differentiate between desire for information and desire for treatment choice. Coulter [31] makes this observation and describes three different approaches to clinical decision making in general health care:

-

1.

Professional choice—the clinician decides and the patient consents.

-

2.

Shared decision making—information is shared and both decide together.

-

3.

Consumer choice—the clinician informs and the patient makes the decision.

Coulter argues that different models may be appropriate at different times. The middle model, shared decision making, is often preferred and there is a growing body of research in this area, although relatively little has been done in psychiatry [32]. She found that studies varied in how much choice patients want, with age, clinical situation, educational status and cultural background being possible factors leading to the variance in findings. This pattern has also been found in specific mental health settings in the US [33].

Choice may, in theory, improve treatment outcomes [34]. This may be by improving patient attitudes to the treatment they have actively chosen, by increasing the patients’ sense of control, or by the patients successfully matching their needs to the appropriate treatment.

Measuring autonomous choice

Ende et al. [35] developed the Autonomy Preference Index (API) as a measure of desire for information and a desire for decision making. This instrument had adequate validity and reliability and was used on 312 general medical patients in the US. They found that, on the whole, patients wanted to have information about their illness but did not want to be principle decision makers. Desire for information was not correlated with preference for decision making. Patients were more likely to want to be part of the decision making process if they were less ill or younger, but individual characteristics were more important than sociodemographic factors in determining desire for decision making. The authors felt their results reflected a desire for ‘paternalism with permission’.

Other scales have been used to measure the degree of involvement that patients want in decision making, including the Control Preferences Scale [36] and the Patient Preferences for Control measure [37]. Both require patients to pick a role description. Using these two scales, Entwistle et al. [38] found that patients picked the same roles for differing reasons, and some picked differing roles for similar reasons when compared to their narrative accounts, and hence questioned the validity of these scales.

The evidence for choice

Two recent studies using the API in mental health to measure patients’ desire to be involved in treatment decisions suggest mental health patients want a significant say in their care. Hamman et al. [39], in a study of 122 inpatients with schizophrenia, found a desire for shared decision making which was slightly greater than patients in primary care from the original US study [35] and very similar findings were found amongst 105 community mental health patients in Cornwall, England [40]. However, neither study suggested patients want a consumerist approach, where the clinician gives the patient options and the patient makes a fully autonomous choice. Most patients want a partnership with the clinician in deciding treatment. In both studies, younger patients were more keen on having a say in treatment.

Are patients actually given choices in their mental health care in the UK? Rycroft-Malone et al. [41] examined nurse–patient interactions in different patient groups including mental health using qualitative methodology. In practice patient choice was restricted, although less so in mental health compared to acute medical and general practice patients. More choice was offered to mental health patients in terms of medication administration times, and the time and venue of appointments. Psychiatric patients have been interviewed in the UK about what they wanted from nursing staff caring from them. A key desire for patients was for nurses to give them information about their condition to empower patients to have a degree of control over treatment interventions [42].

There is evidence that giving patients choice increases patient engagement in mental health. In primary care in the US, Dwight-Johnson et al. [43] gave depressed patients in an intervention group a choice between medication and talking therapy. They compared these patients with a control group who had usual care with no choice. More patients in the intervention group entered treatment (50%) compared with the control group (33%). No outcome data were given for the 742 patients. Rokke et al. [34] studied 40 patients with depression. Two types of self-management treatment were available (cognitive or behavioural). Individuals given a choice of treatment were less likely to drop out of treatment prematurely. There was no difference in treatment outcome between patients given a choice and patients assigned to treatment, although the number of patients was small.

The effect of giving patients choice on mental health outcomes is not clear. Some studies suggest a positive effect on outcome. Alcoholic consumers given treatment choices had better treatment outcomes than consumers with fewer choices [44]. A study on 32 patients with a snake phobia gave 16 patients a choice after seeing videotapes of four different behavioural therapies whilst 16 patients were randomly assigned. Despite the small number of patients, those who chose were significantly better on a behavioural scale after therapy [45]. However, other studies have not demonstrated a definite positive effect. Cocaine users given a choice between group and individual therapy did no better than patients given no choice in most symptom measures, although surprisingly the authors did not emphasise that those who chose their treatment were using cocaine on fewer days per month nine months later [46]. Patient preference randomised controlled trials have not shown a clear effect of patient preference on outcome, possibly due to the low power of the trials [47, 48]. Bedi et al. [49] assessed the effectiveness of the treatment of depression in primary care in a well-designed partially randomised preference trial. This was one of the few quantitative studies in this literature review that included a power calculation. Patients were either randomised (n = 103) or chose (n = 220) between medication and counselling. The patients who chose between the two treatment options did not have better outcomes than those who were randomised to treatment—outcome measures were for symptoms and functioning. This finding was consistent with another preference trial in depression [50]. A study in modified assertive community treatment gave homeless patients with psychosis either a choice of treatment programme or no choice [29]. Of those having treatment at the ACT programme, there was no difference between patients who had had a choice and those that did not in terms of clinical outcome, other than the former group visited the programme more. Manthei et al. [51] gave some patients referred to a community mental health centre in the US a choice of individual therapist whilst others were assigned a therapist. There was no difference in treatment outcome using standardised rating scales, although again the study may have lacked power as only 42 patients were included.

Calsyn et al. [29] suggested that these mixed findings might indicate that giving patients choice results in the patients engaging better and making greater effort in the treatment process. However choice may improve outcomes in patients who are functioning relatively well, but not in patients with more pervasive and severe mental illnesses.

Power

Connotations of power

Postmodern thought questions the concept of objective knowledge. This challenges the idea of clinicians as disinterested observers of evidence—they can use medical knowledge to augment their own power. The issue of power in mental health can be separated into three overlapping areas. First, there is the way the state uses its power in addressing mental health problems. The mentally ill are often the only group of patients who can be forced to receive treatment. The recent proposed reforms of mental health legislation in the UK have led to debates on many relevant issues, including treatability and reciprocity [52], capacity [53] and discrimination of the mentally ill as compared to the physically ill. Thomas and Cahill [54] have suggested that psychiatric patients are so disempowered that many do not feel able to take steps towards empowerment.

Second, there is a more general issue of the power balance between clinicians and patients. As well as the charge that clinicians exert a paternalistic power over patients [55], there are also power differentials between professions often reflecting a dominant model of mental illness. The alleged imbalance of power between clinicians and patients has led to movements critical of psychiatry such as the anti-psychiatry movement, consumer-led services, the alternative treatment movement and critical psychiatry network.

Third, there is the movement for the empowerment of patients. This emphasises the rights of patients to self-determination and their economic situation as consumers of services. Detailed descriptions of the multiple conceptual components of empowerment have been described elsewhere (e.g. [56]). Clearly these three aspects of power in mental illness are not distinct and overlap. In this review we shall not examine the issues around state legislation as this has been explored extensively elsewhere.

Measuring empowerment

In a US study designed to develop an empowerment scale for patients, a group of 10 leaders in the consumer-survivor movement devised a 28-item questionnaire [57]. They found that the items could be grouped into five themes: self-efficacy—self-esteem; power—powerlessness; community activism; optimism—control over the future; and righteous anger (listed in order of their importance in the variance of the scale). This rating scale was completed by 271 patients participating in self-help programmes. Age, gender, ethnicity, education level, employment status and number of hospital admissions were not associated with a greater sense of empowerment. Community activism was related to greater empowerment, and use of services to less empowerment. The scale had a high degree of internal consistency. Wowra and McCarter [58] used the scale on community mental health patients in the US, with 283 patients (a response rate of 16%) completing the questionnaire. They confirmed the order of significance of the five areas described by the first study. Age, gender and race were not associated with the degree of empowerment. However, they found that employment status and level of education were associated with a greater sense of empowerment. The mean score in this study was 2.74, where a score of 4 is most empowered. The average score in the first study was 2.94. It is not clear if this scale is sensitive enough to show change in intervention studies.

Corrigan and Garman [59] have suggested that empowerment includes two factors—empowerment of the self (with higher self-esteem and efficacy) and empowerment within the community (leading to more community confidence). Therefore their research team tested the Empowerment Scale developed by Rogers et al. [57] to evaluate its construct validity [60]. They approached 35 patients with severe mental illness, and also measured symptoms, functioning, intelligence, quality of life, social support and level of need. They found that the scale could be interpreted as dividing into two superordinate factors—self-orientation (associated with self-efficacy, self-esteem and optimism/control of the future) and community orientation (associated with community action, powerlessness and effecting change). Greater community orientation was associated with higher intelligence, greater resources and minority ethnicity. Greater self-orientation was associated with better quality of life, fewer symptoms and better social support.

Three other empowerment scales were developed by Segal et al. [61] with patients with severe mental disabilities. These scales have not been extensively used in the literature.

Evidence for empowerment of patients

Historical overviews of the developments in advocacy and patient empowerment have been well described by Foulks [62] in the US and Peck et al. [63] in England. There is some evidence on empowerment at an organisational level. Geller et al. [64] surveyed mental health services in all states of the US. With a 100% response rate, about one third of states had policies for consumer involvement, one half employed consumers in central offices for mental health and one half employed consumers in field offices. Consumer empowerment was not associated with geographical region or the size of the mental health budget, but was associated with larger sizes of population and better quality of services. In Somerset, England, the development of user involvement over 30 months was measured using qualitative and quantitative methodology [63]. User consultation was evident at management and planning level, but there was little evidence of user control in the system, and involvement at an individual patient level depended on the attitude of individual staff members. Of those patients involved in devising their care plan, 82% said the plan had made a positive impact on their lives. For those who were not involved, the corresponding figure was 12%.

In the UK, national policy states that service users should be involved in all levels of planning and delivery of mental health care [7]. An audit of a rehabilitation service in Nottingham using structured interviews suggested high levels of user involvement in staff recruitment, planning and organising services, with less involvement in eliciting users’ views and evaluation of services [65]. When 137 patients receiving psychiatric care in North London, UK, were asked how satisfied they were with their care, one question asked was whether they had a say in the treatment they received. Only 44% agreed that they did have a say in their care. Younger patients were less likely to agree [66].

Service users have been employed as health care assistants in an assertive outreach team in London, and 45 patients were randomised into having this input or receiving standard care. Those patients receiving help from these health care assistants had better rates of attendance, participated more in social activities, and had fewer social needs. There was no difference in satisfaction with services and there was concern with the amount of sick leave of these workers [67, 68].

Clearly there is an overlap between patient empowerment and interventions that seek to increase the self-efficacy of patients and increase their independence. Fitzsimmons and Fuller [56] reviewed studies showing the positive effect of certain psychosocial interventions that had increased patients’ empowerment through increased self-help, meaningful participation in services, self-esteem and employment. They conclude that the research to date “indicates that empowerment interventions need to occur at many levels throughout a system to be effective”.

Evidence in the power differential between patients and clinicians

The research in this area has been qualitative and has examined abuse, disengagement, alternative service models and the interactions in community mental health care. There has been a literature review of patient empowerment and abuse in mental illness [69]. This concluded that abuse can occur firstly because of power imbalances between patients and clinicians and secondly because conditions that can lead to physical and sexual abuse in general society can occur in mental health services.

A qualitative study examined assertive community treatment in mental health from the viewpoint of 12 patients interviewed using a grounded theory approach. They found that previous disengagement from mental health services was linked with previous coercive interventions. All felt that their voice had not been listened to and had an increased level of arousal around issues of power [70].

The patient empowerment movement led to the development of alternative service models, including consumer-led services. However in a study interviewing users of such a service, McClean [71] concluded that the founding principles had been lost in the growth of these organisations. She concludes that this has lead to a crisis in the movement that has replicated standard mental health agencies, particularly in the divide between providers and receivers of a service. A residential centre set up as an alternative to hospital admission in North Wales was also evaluated by qualitative interview [72]. The centre was intended as a ‘person centred’ environment. They found that however person-centred the approach, issues around the power differential between staff and patients persisted. However patients still valued aspects of the new service.

Colombo et al. [73] examined how decisions are made in multidisciplinary mental health teams in the UK. They interviewed 100 participants, including psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, patients and carers using specific questions to establish what model of mental illness participants used and how decisions are made in clinical care. Whilst different groups emphasised different models of illness, the decisions made were felt to be influenced by the sick role of the patient. The authors stated, “On the one hand patients are unconsciously encouraged, via the sick role, along with its associated rights and obligations, to become passive recipients of care. On the other hand, via notions such as patient empowerment and social inclusion, they are being subjugated to contradictory messages encouraging them to take on more responsibility and to see this as an important civil right... Underlying beliefs about the need to recognise patient rights and autonomy do not sit comfortably along-side structural and implicit support for the sick role.” They conclude that for effective care, patients need to be recognised as part of the multi-disciplinary team.

Discussion

Researchers have examined the connotations of trust, choice and power, developed tools to measure all three and there is a significant research base stressing that they are important to patients. The literature review was limited to PubMed, which may have biased the findings to anglophone journals. Due to the large number of articles identified, they were screened by article title and then abstract, which may have missed some relevant research. However some articles not identified in the search were picked up by references in the identified papers. Whilst we reviewed trust, choice and power as three distinct areas, there were several papers identified by two or three of the different searches, emphasising how these areas overlap. For example research on trust emphasised the importance of clinicians giving patients information and a role in choosing treatments in building trust (e.g. [22]).

Most quantitative research on trust has taken place in the US amongst community population samples or on patients attending family doctors. Trust in individual clinicians has been shown to be high and robust to pressures on this trust [18]. Important variables associated with higher levels of trust are older age of patients and greater continuity of care, both in terms of length of time the patient has known the doctor and the number of consultations. In mental health, qualitative studies in the UK suggest that trust is important to patients, and that again continuity of care is an important aspect to build trust [23, 24]. A study in the US suggests that attention to patients’ concern about medication side effects, confidentiality and continuity of care are important to mental health patients in building trust [25]. Overall the current evidence suggests that trust has not been significantly eroded in health care and is valued by mental health patients in their relationship with clinicians. However quantitative studies on mental health patients are needed including on interventions that might build trust.

There is significant research evidence on patient choice suggesting that patients value choice in their interactions with staff [42] and being given information on their illness and a say in treatment decisions [39, 40]. There is some evidence that in routine care, mental health patients are offered more treatment choices than other areas of medicine [41]. In general and mental health, sociodemographic factors can influence how much choice patients want, but individual variation is also important [31, 33, 35]. Patients given choice of treatment in mental health may be more likely to enter treatment and stay in treatment [34, 43]. The effect of patient choice on clinical outcome is variable. Limited evidence may suggest that in less severe illnesses choice has a positive effect on outcomes, whilst this is not so in more severe conditions. However the number of studies is small and of varying quality.

Empowerment scales have been developed in mental health and have suggested multiple domains [57, 59]. It is unclear if these scales can be used in intervention studies, as their sensitivity to change is not established. There is a research base examining power issues in the relationship between patients and clinicians and it is mostly qualitative in nature. The issue of a power imbalance matters to at least some patients, and can be a factor in patients disengaging from services [70]. The ideological conflict between the patient in the sick role and patient empowerment is evident when different stakeholders are interviewed [73]. Setting up patient-led services and patient-centred services to try to overcome this power imbalance is not necessarily successful at achieving that aim, as new power imbalances can emerge [71, 72]. Studies on patient empowerment suggest that practical steps have been introduced at a managerial and planning level, but this is harder to implement at an individual care level, despite some evidence that patients feel it improves their care [63]. Employing users of services as health care assistants is a relatively new development and may improve outcomes [67, 68].

Conclusions

There is a substantial research base in trust, choice and power in mental health care. The methodology used has often been qualitative, but quantitative studies have also been fruitful, and empirical measures of trust, autonomy and empowerment have been developed, although for trust not validated in mental health. Qualitative methodology, whilst in some aspects more consistent with postmodern thought, seeks to reflect individual experience rather than population probabilities. Nevertheless, qualitative research often aims to find generalisable conclusions, partly to justify funding and publication.

The research methodology has been disparate, needs developing, and would benefit from being consistent and coherent. Quality standards of methodology do not mean identical methodology, but standards need to have clear definitions and operationalised approaches. The studies that have been described have met these criteria to a varying degree. In the introduction it was postulated that the debate about trust, choice and power may have been influenced by postmodern cultural change. There is an inherent tension in studying postmodern ideas using clearly modernist methodologies. Is the paradigm of postmodernism an excuse for not researching ideas? We would argue that it is acceptable to use both empirical and non-empirical evidence to evaluate mental health care. Furthermore funding bodies and journals will demand agreed consensual quality standards in research methodologies.

The issue of trust in mental health clinicians has not been as well researched as it has in other areas of medicine. Trust in doctors appears to be robustly high in other medical disciplines and we need to discover if this is the case in psychiatry, as well as the importance of continuity of care and age in influencing trust. The area of patient choice has had more evaluation in mental health. Offering patients choice appears to be what patients want. However, in general health care and mental health, they do not appear to want a consumerist system but rather a partnership with their clinician where the knowledge of the expert is utilised by the patient. Giving patients choice seems to increase engagement with services, but effects on outcome are variable. International comparisons of patient choice may well be enlightening, as some consumerist systems offer much more patient choice than others. Patient empowerment in mental health has developed at an organisational level. The challenge is to empower patients in their individual care as currently the evidence suggests that this has not been established.

References

Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK (1997) Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull 23: 637–651

Lyotard J-F (1984) The postmodern condition: a report on knowledge. Manchester University Press, Manchester

Foucault M (2001) Madness and civilisation. Routledge, London

Gray JM (1999) Postmodern medicine. Lancet 354: 1550–1553

Bracken PJ (2003) Postmodernism and psychiatry. Curr Opin Psychiatry 16: 673–677

Laugharne R, Laugharne J (2002) Psychiatry, postmodernism and post-normal science. J Roy Soc Med 95: 207–210

Department of Health (1999) Modernising mental health services. HMSO, London

O’Neill O (2002) A question of trust. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Goudge J, Gilson L (2005) How can trust be investigated? Drawing lessons from past experience. Soc Sci Med 61: 1439–1451

Cooper DE (1985) Trust. J Med Ethics 11: 92–93

Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, et al. (2001) Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured and does it matter? Millbank Q 79: 613–639

Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E (2002) Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev 59: 293–318

Hall MA, Camacho F, Dugan E, et al. (2002) Trust in the medical profession: conceptual and measurement issues. Health Serv Res 37: 1419–1439

Anderson LA, Dedrick RF (1990) Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationship. Psychol Rep 67: 1091

Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WA, et al. (1998) Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract 47: 213–220

Kao AC, Green DC, Davies NA, et al. (1998) Patients’ trust in their physicians. J Gen Intern Med 13: 681–686

La Veist TA, Nikerson K, Bowie JV (2000) Atttitudes about racism, medical mistrust and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev 57: 146–161

Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DA (1999) Further validation and reliability testing of the trust in physician scale. Med Care 37: 510–517

Mechanic D (1996) Changing medical organisation and the erosion of trust. Milbank Q 74: 171–189

Blendon RJ, Brodie M, Benson JM (1998) Understanding the managed care backlash. Health Aff 17: 80–94

Mainous AG, Baker R, Love MM, Gray DP, Gill JM (2001) Continuity of care and trust in one’s physician: evidence from primary care in the United States and the United Kingdom. Fam Med 33: 22–27

Balkrishnan R, Dugan E, Camacho FT, et al. (2003) Trust and satisfaction with physicians, insurers and the medical profession. Med Care 41: 1058–1064

Kai J, Crosland A (2001) Perspectives of people with enduring mental ill health from a community-based qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 51: 730–736

Hannigan B, Bartlett H, Clilverd A (1997) Improving health and social functioning: perspectives of mental health service users. J Ment Health 6: 613–619

Mechanic D, Meyer S (2000) Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Soc Sci Med 51: 657–668

Thom DH, Bloch DA, Segal ES (1999) An intervention to increase patients’ trust in their physicians. Acad Med 74: 195–198

Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, et al. (2002) Public attitude to compulsory admission of mentally ill people. Acta Psychiatr Scand 105: 385–389

Quill TE, Brody H (1996) Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: finding a balance between patient power and patient choice. Ann Intern Med 125: 763–769

Calsyn RJ, Winter JP, Morse GA (2000) Do consumers who have a choice of treatment have better outcomes? Community Ment Health J 36: 149–160

Salem DA (1990) Community based services and resources: the significance of choice and diversity. Am J Community Psychol 18: 909–915

Coulter A (2003) The autonomous patient: ending paternalism in medical care. The Nuffield Trust, TSO, London

Hamann J, Leucht S, Kissling W (2003) Shared decision making in psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand 107: 403–409

Freiman MP, Zuvekas SH (2000) Determinants of ambulatory treatment mode for mental illness. Health Econ 9: 423–434

Rokke PD, Tomhave JA, Jocic Z (1999) The role of client choice and target selection in self management therapy for depression in older adults. Psychol Aging 14: 155–169

Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, et al. (1989) Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy. J Gen Intern Med 4: 23–30

Degner LF, Sloan JA (1992) Decision making during serious illness; what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol 45: 941–950

Bradley JG, Zia MJ, Hamilton N (1996) Patient preferences for control in medical decision making: a scenario-based approach. Fam Med 28: 496–501

Entwistle VA, Skea ZC, O’Donnell MT (2001) Decisions about treatment: interpretations of two measures of control by women having a hysterectomy. Soc Sci Med 53: 721–732

Hamman J, Cohen R, Leucht S, Busch R, Kissling W (2005) Do patients with schizophrenia wish to be involved in decisions about their medical treatment? Am J Psychiatry 162: 2382–2384

Hill SA, Laugharne R (2006) Decision making and information seeking preferences among psychiatric patients. J Ment Health 15: 75–84

Rycroft-Malone J, Latter S, Yerrel P, et al. (2001) Consumerism in health care: the case of medication education. J Nurs Manage 9: 221–230

Edwards K (2000) Service users and mental health nursing. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 7: 555–565

Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, et al. (2001) Can quality improvement programmes for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment. Med Care 39: 934–944

Kissen B, Platz A, Su W (1971) Selective factors in treatment choice and outcome in alcoholics. In: Mello N, Mendelson J (eds) Recent advances in studies of alcoholism. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, pp 781–802

Devine DA, Fernald PS (1973) Outcomes effects of receiving a preferred, randomly assigned or nonpreferred therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 41: 104–107

Sterling RC, Gottheil E, Glassman G, Weinstein SP, Serota RD (1997) Patient treatment choice and compliance: data from a substance misuse programme. Am J Addict 6: 168–176

Howard L, Thornicroft G (2006) Patient preference randomised controlled trials in mental health research. Br J Psychiatry 188: 303–304

King M, Nazareth I, Lampe F, Bower P, Chandler M, Morou M, Sibbald B, Lai R (2005) Impact of participant and physician intervention preferences on randomised trials—a systemic review. J Am Med Assoc 293:1089–1099

Bedi N, Chilvers C, Churchill R, Dewey M, Duggan C, Fielding K, et al. (2000) Assessing effectiveness of treatment of depression in primary care: partially randomised preference trial. Br J Psychiatry 177: 312–318

Ward E, King M, Lloyd M, Bower P, Sibbald B, Farrelly S, Gabbay M, Tarrier N, Addington-Hall J (2000) Randomised controlled trial of non-directive counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy and usual general practitioner care for patients with depression. I. Clinical effectiveness. Br Med J 321: 1383–1391

Manthei RJ, Vitalo RL, Ivey AE (1982) The effect of client choice of therapist on therapy outcome. Community Ment Health J 18: 220–227

Welsh S, Deahl MP (2002) Modern psychiatric ethics. Lancet 359: 253–255

Holloway F, Szmukler G (2003) Involuntary psychiatric treatment: capacity should be central to decision making. J Ment Health 12: 443–447

Thomas P, Cahill AB (2004) Compulsion and psychiatry—the role of advance statements. Br Med J 329: 122–123

McCubbin M, Cohen D (1996) Extremely unbalanced: interest divergence and power disparities between clients and psychiatry. Int J Law Psychiatry 19: 1–25

Fitzsimons S, Fuller R (2002) Empowerment and its implications for clinical practice in mental health: a review. J Ment Health 11: 481–499

Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, Crean T (1997) A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv 48: 1042–1047

Wowra SA, McCarter R (1999) Validation of the empowerment scale with an outpatient mental health population. Psychiatr Serv 50: 959–961

Corrigan PW, Garman AN (1997) Some considerations for research on consumer empowerment and psychosocial interventions. Psychiatr Serv 48: 347–352

Corrigan PW, Faber D, Rashid F, Leary M (1999) The construct validity of empowerment among consumers of mental health services. Schizophr Res 38: 77–84

Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T (1995) Measuring empowerment in client-run self help agencies. Community Ment Health J 31: 215–227

Foulkes EF (2000) Advocating for persons who are mentally ill: a history of mutual empowerment of patients and profession. Adm Policy Ment Health 27: 353–367

Peck E, Gulliver P, Towel D (2002) Information, consultation or control: user involvement in mental health services in England at the turn of the century. J Ment Health 11: 441–451

Geller JL, Brown JM, Fisher WH, Grudzinskas A, Manning T (1998) A national survey of “consumer empowerment” at the state level. Psychiatr Serv 49: 498–503

Diamond B, Parkin G, Morris K, Bettinis J, Bettesworth C (2003) User involvement: substance or spin? J Ment Health 12: 613–626

Barker DA, Shergill SS, Higginson I, Orrell M (1996) Patients’ views towards care received from psychiatrists. Br J Psychiatry 168: 641–646

Craig T, Doherty I, Jamieson-Craig R, Boocock A, Attafua G (2004) The consumer-employee as a member of a mental health assertive outreach team. I. Clinical and social outcomes. J Ment Health 13: 59–69

Doherty I, Craig T, Attafua G, Boocock A, Jamieson-Craig R (2004) The consumer-employee as a member of a mental health assertive outreach team. II. Impressions of consumer-employees and other team members. J Ment Health 13: 71–81

Kumar S (2000) Client empowerment in psychiatry and the professional abuse of clients: where do we stand? Int J Psychiatry Med 30: 61–70

Watts J, Priebe S (2002) A phenomenological account of users’ experiences of assertive community treatment. Bioethics 16: 439–454

McLean A (1995) Empowerment and the psychiatric consumer/ ex-patient movement in the United States: contraindications, crisis and challenges. Soc Sci Med 40: 1053–1071

Williams B, Cattell D, Greenwood M, Lefevre S, Murray I, Thomas P (1999) Exploring person-centredness: user perspectives of a model of social psychiatry. Health Soc Care Community 7: 475–482

Colombo A, Bendelow G, Fulford B, Williams S (2003) Evaluating the influence of implicit models of mental disorder processes of shared decision making within community based multi-disciplinary teams. Soc Sci Med 56: 1557–1570

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Both authors are psychiatrists working in the UK.