Abstract

Background

There has been little prospective investigation of the relationship between adult attachment style and clinical levels of anxiety and major depression. This paper seeks to address this, as well as examining the potentially mediating role of adult insecure attachment styles in the relationship between childhood adverse experience and adult disorder.

Methods

154 high-risk community women studied in 1990–1995, were followed-up in 1995–1999 to test the role of insecure attachment style in predicting new episodes of anxiety and/or major depressive disorder. The Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA) and the Attachment Style Interview (ASI) were administered at first interview and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) administered at first and follow-up interview. Major depression and clinical level anxiety disorders (GAD, Social Phobia or Panic and/or Agoraphobia) were assessed at first contact and for the intervening follow-up period.

Results

55% (85/154) of the women had at least one case level disorder in the follow-up period. Only markedly or moderately (but not mildly) insecure attachment styles predicted both major depression and case anxiety in follow-up. Some specificity was determined with Fearful style significantly associated both with depression and Social Phobia, and Angry-Dismissive style only with GAD. Attachment style was unrelated to Panic Disorder and/or Agoraphobia. In addition, Fearful and Angry-dismissive styles were shown to partially mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and depression or anxiety.

Conclusion

In order to correctly interpret lifespan models of adult psychiatric disorder, it is necessary to test for mediating factors. Attachment theory provides a framework for explaining how dysfunctional interpersonal style arising from early childhood perpetuates vulnerability to affective disorders. This has implications for intervention and treatment to break cycles of risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attachment theory has increasingly been utilised as a powerful explanatory model for psychopathology [1, 2]. From its initial focus on parenting behaviour, its application has been extended to account for psychosocial factors associated with major depressive disorder [3] and more recently to anxiety disorders [4]. This has particular relevance for social psychological approaches focused on adult attachment, as evidenced by the nature and quality of relationships with partner and other supportive adults [5]. Insecure attachment styles (Anxious/Ambivalent or Avoidant) have been shown to be associated with higher levels of psychopathology including depression, anxiety and substance abuse [6].

Whereas secure attachment style consistently relates to better mental health, there has been little or inconsistent specificity in relating type of insecure attachment style to type of psychiatric disorder. While some studies show an association between depressive symptoms and the more anxious/ambivalent styles such as ‘Preoccupied/enmeshed’ [7] and ‘Fearful’ [8], others have highlighted ‘Avoidant’ styles [9]. Yet other studies have shown no differentiation with both of the insecure styles relating to depression [6]. Fewer studies have examined anxiety disorder as an outcome, but associated styles include Preoccupied [2, 4] and ‘Unresolved’ classifications [10].

Failure to reliably replicate specificity of style to disorder has been attributed to the wide divergence of measures and categorisations of attachment styles [4]. Future research into associations between different attachment styles and different types of disorder needs to investigate related psychosocial factors and potential mediation in order to increase our understanding of the underlying processes involved.

Attachment theory has been adopted as a framework for understanding the relationship between social support and depression [e.g. 3, 11] and is beginning to be similarly utilised for anxiety disorders [12]. There is empirical evidence that deficiencies of social networks are relevant for increased vulnerability to both depression and anxiety disorders. Although there has been more extensive investigation of the role of poor support in depressive vulnerability [13], there is also increasing evidence that anxiety disorders, particularly Social Anxiety, are related to decreased social networks [14], impaired relationship functioning [15] and distorted perceptions of the self as being devalued in social interactions [16]. Davila and Beck [17] in a series of 168 young adults with anxiety, found that higher levels of social anxiety were correlated with poorer inter-personal styles showing less assertiveness, more conflict avoidance, more avoidance of expressing emotion and greater inter-personal dependency. Lack of assertiveness and over-reliance on others mediated the relationship between social anxiety and inter-personal stress [17]. Social anxiety was found to be associated with both avoidance (through lack of assertiveness) and dependence (over-reliance on others). This is consistent with the category of Fearful attachment style characterised by its conflicting needs for intimacy and independence [18]. Eng and colleagues [4] examined social anxiety and attachment in an adult clinic population and found that Preoccupied attachment style was associated with less comfort in relationships, less trust and more anxiety at rejection and abandonment. Both the fear and the expectation that others will provide negative evaluation, is argued to be at the base of such responses [19].

A central tenet of attachment theory is a lifespan approach whereby the origins of insecure attachment style stem from adverse childhood experience [20]. Inconsistent and insensitive parenting, along with parental separation and more extreme experiences of neglect and abuse, have all been identified as aetiological precursors of latter attachment difficulties [11, 21]. These early adverse experiences are also frequently associated with major depressive and anxiety disorders in adulthood [22–24]. The attachment model closely parallels other psychosocial models of affective disorder. For example, the stress model investigated by Brown, Harris and colleagues, which identified childhood neglect/abuse, poor support and low self-esteem as vulnerability factors for depression, has close parallels with attachment models [25]. However, testing the attachment model with reliable measurement and in prospective study designs to determine causal relationships is still relatively rare. There is a clear need not only to further elucidate the relationship of childhood adversity in relation to types of attachment style, but also to examine whether attachment style has a mediating role in the relationship between childhood adversity and depressive and/or anxiety disorders. The mediating role is important in understanding early life impacts and their perpetuation or discontinuity [21, 26, 27]. This is best tested in a prospective design where the reporting of attachment style and disorder are separated and the time order more easily determined.

Previous investigation of a contextualised, support-focused interview—the Attachment Style Interview (ASI)—has shown a significant association with major depression in a largely high-risk community-based sample of women [28]. This association held for insecure styles—Enmeshed, Fearful and Angry-Dismissive—but not for those categorised as Withdrawn. This also held only at more dysfunctional levels of such styles (i.e. those categorised as ‘markedly’ or ‘moderately’ insecure), determined by poor ability to make and maintain supportive relationships together with more extreme attitudes of inter-personal avoidance or dependence, fear or anger. In contrast, those with only ‘mildly’ insecure styles were at no higher risk of disorder than those ‘clearly secure’ when concurrent disorder was controlled. High levels of insecure attachment style were significantly associated with the experience of childhood neglect, physical or sexual abuse. In particular Fearful and Angry-Dismissive styles had the highest correlation with adverse childhood experience [11]. The same interview assessment used in a cross-European/US study of postnatal depression showed that the interview could be used reliably in a number of settings across Europe and the USA and that insecure attachment style related to depression in the maternity context, including postnatal depression assessed prospectively [29].

The analysis presented here aims to reinvestigate the relationship between attachment style and disorder using the ASI in a follow-up of a previously reported series [28]. It adds to the previous study by investigating the relationship prospectively and examining outcomes for anxiety disorders in addition to major depressive disorder. In also tests the mediating properties of attachment style in the relationship between childhood adversity and adult depressive and/or anxiety disorder.

Three hypotheses were tested:

-

(1)

Insecure attachment styles are significantly associated with new episodes of anxiety disorders and/or major depression;

-

(2)

Childhood neglect/abuse is associated with insecure attachment style.

-

(3)

Insecure attachment styles mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and affective disorder.

In addition, the specific relationship of type of attachment style to childhood adversity and different disorder outcomes is explored.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of 154 community women aged between 26 years and 59 years, originally studied in 1990–1995, who agreed to a follow-up interview an average of three years later as part of an MRC funded programme. The sample was selected from North London GP practices [22, 30]. The two-stage selection involved sending out a large number of screening questionnaires (7,000 with 45% response rate) in order to determine suitability by the presence of either childhood or adult vulnerability characteristics (40% of screen)Footnote 1. Suitable individuals were then interviewed. Full details of the original sample selection are given elsewhere [28].

The current follow-up in 1995–1999 focused on selecting individuals in three groups: one selected at original contact for adult vulnerability characteristics, another for childhood vulnerability characteristics, and one as a comparison group. Good compliance (80%) was achieved for the women approached for re-interview.Footnote 2 The three groups of women were selected as follows:

Adult vulnerability (n = 57)

Women were selected for the first phase of the study, on the basis of having poor support (defined as negative interaction with partner or lack of close confidant) or because of conflict with a child in the household. All the women had at least one child living at home. The original series of 105 reduced to 95 in contact at the end of the first prospective period (1995) and 21 were not approached due to absence of family members suitable for the intergenerational component of a parallel study [31]. Of the remaining 74, 77% (57) agreed to be re-interviewed at follow-up. This represented 60% of the original series. Analysis of first interview information shows that this group did not differ at interview 1 from the full series of 105 in terms of demographic or risk characteristics (figures available on request).

Childhood vulnerability (n = 55)

The original series of 60 women were selected for adverse childhood experience under age 17 and having a sister within 5 years of age also agreeing to interview. Within each sister pair only the initially screened woman was contacted for follow-up. Of these, 77% (46) agreed to the follow-up. Where a woman refused or was unavailable her sister was approached as a replacement, with an extra 9 women included in this way.

Comparison series (n = 42)

The original comparison women were recruited as consecutive responders to the screening questionnaire from the North London surgeries, if they had a sister within 5 years of age also agreeing to interview. The 40 women originally screened were approached for follow-up and 88% (35) agreed to be re-interviewed. For the 5 unavailable, a sister was approached and agreed to be a replacement. An additional 2 women from the sisters group were also approached for a parallel inter-generational project and included.

The childhood and attachment assessments were undertaken in the first phase of the study together with psychiatric disorder. A further psychiatric assessment was made at follow-up interview to reflect the intervening time period an average of 3 years (range 1–4). After establishing the prevalence of risk factors in these groups, the bulk of the following analysis is completed on the combined groups in intra-individual analysis. In terms of demographics around a third of the women (35%) were working-class, over two thirds (67%) were in employment, just over half were married or cohabiting (55%) and most (76%) were mothers, with just under a third of the series (26%) single mothers at first interview. All women were interviewed in their own homes at both waves of the study.

Ethical permission was granted by Islington LREC, with signed consent obtained at both stages of the study.

Measures

The predictor variable was childhood adversity and different attachment styles acted as both predictors and potential mediators of disorder. The predictors were assessed at first interview and the criterion variables of episodes of anxiety and depression were measured at first and follow-up interviews covering the full intervening period.

(1) Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA)

Adverse childhood experience was assessed by means of the CECA interview [32]. This investigator-based interview measures adverse experiences before age 17, including neglect, physical and sexual abuse. It has good reliability and validity [30].

-

(a)

Neglect was defined in terms of parents’ disinterest in material care (feeding and clothing), health, schoolwork and friendships, encompassing each natural parent and parent surrogate with whom the child lived for at least 12 months prior to age 17. Neglect was quantified by means of a four-point scale (marked, moderate, some/mild and little/none). A rating of severe neglect (marked or moderate) required at least two or more indicators of neglect over a 12-month period.

-

(b)

Physical abuse was defined as physical attacks by parents or other older household members and measured on a 4-point scale. A range of attacks were assessed but those rated as severe (marked or moderate) were usually repeated and potentially harmful attacks with implements such as belts or sticks or by means of punching or kicking.

-

(c)

Sexual abuse involved physical contact or approach of a sexual nature by any adult (excluding consensual sexual contact with peers). Severity was again measured by means of a 4-point scale. Severe sexual abuse (marked or moderate) included all repeated sexual contacts with an adult or single incidents of a serious nature such as rape or sexual contact with a family member.

Reliability of ratings was increased through reference to manualised benchmarked examples and consensus team agreement. By aggregation of all three subscales of adverse childhood experiences, a dichotomous index of childhood neglect/abuse was constructed accounting for any one severe experience of either neglect or physical or sexual abuse before age 17.

(2) Attachment Style Interview (ASI)

The ASI is an investigator-based interview [28] assessing attachment styles based on the ability to make and maintain supportive relationships together with attitudes about closeness to/ distance from others and fear/anger in relationships. Inter-rater reliability and other psychometric properties of the measure are good [28, 29]. The ASI provides a global assessment of support by incorporating the quality of relationship with the partner and up to two very close adults. The criterion of having at least two supportive relationships provides the framework for a judgement of good ‘ability to make and maintain relationships’ which in turn provides the basis for rating the degree of attachment security. In addition seven attitudinal ASI-scales are scored to determine types of avoidance (e.g. mistrust, constraints on closeness, high self-reliance and fear of rejection) and anxious/ambivalence (e.g. desire for engagement, fear of separation and anger). These attitudinal scales enable a classification of both the type of insecure attachment (Enmeshed, Fearful, Angry-dismissive, Withdrawn or Clearly Secure), and the degree of insecure attachment style (markedly, moderately, mildly or not insecure). Reliability of these ratings was increased by reference to benchmark manual examples and use of consensus team agreement on all ratings.

The total ASI scale allowed for assessing each of the four insecure attachment styles (Enmeshed, Fearful, Angry-Dismissive and Withdrawn) at three levels (marked, moderate, or mild). In order to contrast the styles in the analysis the final 13-point scale was disaggregated into dichotomous dummy variables representing marked/moderate levels of each of the four insecure styles versus ‘mild’ levels or clearly secure.

(3) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

The SCID [33] was used to measure the outcome (criterion) variables within the average three-year follow-up period. Assessment of anxiety disorders encompassed Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Panic Disorder and/or Agoraphobia and Social Phobia. A dichotomous index of case anxiety in the follow-up period reflected diagnosis of any one of these disorders. In addition, major depressive disorder was also assessed and a dichotomous index of either major depression or case anxiety was derived. Presence of case level anxiety and/or depression at point of first interview (N = 51) was used as an exclusion criterion for certain analyses in order to control for attachment ratings which may have been confounded with ongoing disorder. An assessment was also made of lifetime previous episodes of disorder from the age of 17 up until the first interview. An index of lifetime disorder including chronic (12 months or more) or recurrent (2 or more) episodes was used to denote significant history of affective disorder.

Model and statistical analyses

Table 1 represents the model studied based on logistic regression analysis. Thus childhood experience was the predictor variable (X) insecure attachment styles both predictor variables and potential mediators (M) and adult disorder the criterion variable (Y). Due to the dichotomous nature of all variables binary logistic regression analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 12.0 for Windows) to examine the relationship of the independent variables to disorder outcome.

The mediational hypotheses were tested by means of the well established, and still widely used, approach of Barron and Kenney [34]. A variable is said to mediate the relationship between a predictor and an outcome variable (criterion) if the predictor first has an effect on the mediator variable and this in turn influences the outcome variable. Barron and Kenny’s 1986 approach to establish mediation incorporates testing a series of regression models in terms of the three inherent assumptions:

-

1)

The predictor variable (X) must significantly effect the criterion (Y);

-

2)

The predictor (X) must also be shown to significantly effect the mediator (M);

-

3)

The mediator (M) must have a significant effect on the criterion (Y) in the third equation when controlling for the predictor (X). To test this logistic regression analyses has to be carried out, using—in this analysis—X (childhood adversity) and M (insecure attachment style) as predictors, and Y(depression or anxiety) as the outcome or criterion variable. Total and partial mediation can be differentiated by the final odds-ratio of X and M predicting Y, where X (childhood adversity) is no longer significantly related to Y (depression or anxiety). Where this odds-ratio reduces to zero, the mediation is total.

Finally binary log-linear path analysis was used to identify significant path coefficients of childhood experience and different attachment styles and disorder. Path analysis is suitable for use with dichotomous and observed variables with single indicators to identify potential causal pathways [35]. The required time ordering of variables was aided by the prospective nature of the design with regard to new episodes of disorder.

Results

(1) Prevalence of risks and disorder

(a) Disorder

Rates of case anxiety and major depression in the follow-up period were similar at 36% (56/154) and 40% (62/154) respectively, with 55% (85/154) of the series having at least one disorder in the follow-up period and 23% (35/154) having both comorbidly. GAD proved the most prevalent form of anxiety disorder at 20% (30/154), around twice as common as Social Phobia at 10% (15/154) or Panic and/or Agoraphobia at 12% (18/154). Expected differences in rates of overall disorder were found between the comparison group (18%) and the two vulnerable groups: 44% for the adult risk group compared to 39% for the child risk group (P < 0.01).

Because of the high-risk nature of the series, and their age, the disorder experienced during the study period was usually not a first episode of disorder. In the series as a whole 40% (61/154) had experienced lifetime chronic or recurrent disorder prior to interview 1. The presence of lifetime previous disorder was more common among individuals also experiencing disorder in the follow-up period: 57% (48/85) versus 19% (13/69) with no disorder at follow-up (P < 0.0001). As expected, rates of previous chronic or recurrent lifetime disorder in the vulnerable groups were higher (33% for the adult risk group and 58% for the childhood risk group) than the comparison group (24%, P < 0.001, 2df). Therefore the resulting analysis concerns prediction of a particular recent episode of disorder, not of first onset of disorder, for more than half of the series. In addition 51 women were identified as being in episode at point of first interview when attachment style was assessed and are excluded for certain of the analyses below.

(b) Attachment security

48% (74/154) of the full series displayed highly (i.e. markedly or moderately) insecure attachment styles, 18% (27/154) showed only mildly insecure styles, and 34% (53/154) had a clearly secure attachment style. Highly insecure style was positively related to membership in one of the two vulnerability groups: 65% (37/57) in the adult risk group and 51% (28/55) in the child risk group had highly insecure style, compared to only 22% (9/42) in the comparison group (P < 0.0001, df = 2). Fearful attachment style was the most prevalent style at 23% (35/154), around three times more common than Enmeshed style with 7% (11/154) or Withdrawn style with 8%, (12/154) and twice as prevalent as Angry-dismissive style with 10% (14/154).

(c) Childhood adversity

Severe neglect, physical or sexual abuse occurred in 59% (91/154) of women in this high-risk series. The rate in the comparison series was 24% (P < 0.001) similar to the representative rate for women found in the same inner-city area in prior studies [32]. The rate in the combined high-risk group was 72% (81/112), this high rate in part due to the selection criteria.

(2) Attachment style and new episode of disorder

(a) Degree of insecure attachment

Degree of insecurity was significantly related to both Major Depression and Anxiety outcomes (see Table 2). Consistent with previous analyses, only marked and moderate levels of insecure style were significantly associated with the combined disorder outcome (major depression and/or case anxiety) in follow-up, whereas mild levels of insecurity did not relate to disorder prospectively (see Table 2). These significant associations remained after controlling for disorder at point of first interview (N = 51), with rates of 80% (4/5), 54% (19/35), 29% (6/21) and 17% (7/42) respectively for marked, moderate, mild and no insecurity among the 103 with no disorder at first contact (P < 0.001). Although there was some suggestion that mildly insecure style might have been related to case anxiety, this was not supported by logistic regression analyses. Logistic regression showed that marked/moderate insecurity significantly related to disorder in follow-up (OR = 6.67, Wald = 12.99, 1df, P < 0.001) whereas mildly insecure attachment did not add to the model (OR = 2.00, Wald = 1.18, 1df, NS) nor did the sample group membership (OR = 1.05, Wald = 0.04, 1df, NS) when controls were made for disorder at first interview (overall goodness of ft of model = 70.87%).

(b) Type of insecure attachment style

Overall attachment style (as measured by the total ASI scale reflecting both type and degree of insecurity) was highly correlated with all disorder outcomes apart from Panic and/or Agoraphobia. Thus it related to both major depression and case anxiety in the follow-up period, as well as social phobia and GAD (see Table 3, row 1). Cases of comorbidity (those with two or more disorders), were not associated with any increased levels of insecure attachment. When separate analyses for each type of insecure attachment style were conducted on dichotomous variables, it emerged that whereas Enmeshed and WithdrawnFootnote 3 style had little association with disorder, Fearful and Angry-Dismissive styles were significantly correlated with various disorders. Specifically, Fearful style related to social phobia, overall case anxiety and major depression (Table 3, row 4). Angry-dismissive style related to GAD and overall Anxiety (Table 3, row 5).

(c) Childhood experience and attachment style

Overall attachment style was significantly associated with childhood neglect or abuse (r = 0.30, P < 0.0001). Childhood adversity showed a dose-response effect in its relation to degree of insecurity of attachment style. Thus the proportion with childhood adversity was 92% (11/12) in those markedly insecure, 74% (46/62) in those moderately insecure, 52% (14/27) in those mildly insecure and 38% (20/53) in those clearly secure (P < 0.0001, df = 3). When the full attachment scale was examined in relation to childhood neglect/abuse, there was evidence of an increased rate through all the insecure styles (with rates ranging from 64% to 88%) compared to only to 43% for those securely attached (P < 0.001). However examining each dichotomous highly insecure style in relation to the childhood adversity index showed significant associations only for Fearful (K = 0.19, P < 0.01) and Angry-Dismissive (K = 0.10, P < 0.01) and not for Enmeshed (K = 0.02, ns) or Withdrawn (K = 0.04, ns) styles.

(d) Childhood experience, attachment style and adult disorder

Binary logistic regression confirmed that only Fearful and Angry-dismissive styles were significantly related to new episodes of depression or anxiety in the follow-up period, and that childhood adversity no longer related to disorder when attachment styles were included. (This also held when both group membership and disorder at first contact were entered as control variables). (Table 4)

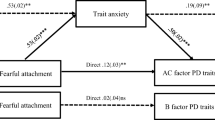

Binary log-linear path analysis was undertaken to examine the relationship between childhood neglect/abuse (predictor variable), highly insecure attachment styles (potential mediator variables) and the outcome (criterion variables) anxiety and/or depression in the follow-up period. Figure 1 shows the significant path coefficients between childhood neglect/abuse and highly Fearful or Angry-Dismissive attachment styles, and between these and depression/anxiety in the follow-up period.

Tests of a mediating role of Fearful and Angry-dismissive attachment styles in the relationship between childhood adversity and anxiety/depression at follow-up were carried out. Figure 2 summarises the results of the three separate analyses using binary logistic regression for anxiety or depression (based on the results shown in the Appendix). Childhood adversity dropped out of the model once Fearful or Angry-Dismissive attachment styles were simultaneously examined in terms of both criteria disorder (anxiety and/or major depression). However, given that the resulting non-significant odds-ratio from childhood adversity to disorders was higher than zero (OR = 1.42) only partial mediation can be claimed.

Discussion

Insecure attachment style was predictive of new episodes of anxiety disorders and major depression in a high-risk series of community women within an intervening follow-up period. The relationship held for GAD and Social Phobia, but not for Panic Disorder and/or Agoraphobia. Analysis of the type of highly insecure style showed that Fearful and Angry-Dismissive styles represented the two insecure attachment types most consistently related to disorder. In terms of specificity, while Fearful style related to social anxiety, Angry-Dismissive style related to GAD. Also, while Fearful style related both to Anxiety Disorder and to Major Depression, Angry-Dismissive style related only to Anxiety Disorder and not to Major Depression. The hypothesised relationship between childhood neglect/abuse and insecure attachment style was confirmed, with Fearful and Angry-dismissive styles again the most highly associated. Furthermore Fearful and Angry-dismissive attachment styles were shown to partially mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and disorder.

The significant associations of Fearful and Angry-dismissive styles with depressive disorder replicated the findings of an earlier study investigating a larger retrospective assessment of the same series [28]. However, in the larger series Enmeshed attachment style was also significantly associated with major depression. This was not replicated in the follow-up study. This somewhat unexpected finding - that such anxious/ambivalent attachment style was not associated with anxiety outcomes - may have been attributable to its low prevalence, features of the sample selection and controls implemented for disorder at first interview. For example, of eleven women with highly Enmeshed style at first interview, five were in episode of disorder, leaving only six to investigate for further prospective analysis. This ‘attrition’ rate is likely to have reduced the statistical power. However, even in the larger study series Enmeshed attachment style was not significantly associated with childhood adversity, thus excluding it as a potential mediating factor. Further investigation of Enmeshed attachment styles is needed to understand its relationship to early experience and disorder among samples where it is more prevalent, for example in younger age groups [13].

Limitations

The study’s inherent limitations will be briefly addressed:

-

1.

The sample was highly selected, consisting of mainly high-risk women. Although compliance among these individuals with follow-up interview was high, there is a need for future research to replicate the findings on representative series (and those including men) to test the generalisability of the model.

-

2.

Despite the study’s prospective design, retrospective measures had to be utilised for childhood adversity and these were assessed at the same point as the attachment style assessment. Although the CECA measure is shown to be robust retrospectively, resulting from its thorough questioning and scoring procedure, the procedure incorporates risk of biased retrospective reporting.

-

3.

Due to the original study selection criteria, and the epidemiological rather than experimental design, it was impracticable to control in the selection for lifetime disorder and that occurring in teenage years. Thus the implications of the analysis are limited to recent, often recurrent, adult episodes with the impact of early life disorder or first onset not examined. In addition issues of recent chronic disorder become a complicating factor in this prospective design in seeking new onsets of disorder. In addition the high co-morbidity of anxiety and depression makes the search for specificity of effects and any differentiation in types of attachment style in the mediation model more difficult to achieve.

-

4.

The model presented here is incomplete as shown by the partial mediation, and this is likely to be due to the absence of a measure of recent stressors. Onsets of affective disorder are shown to be provoked by severe life events, with vulnerability factors such as insecure attachment style only being activated under stress [25]. Given that in attachment theory stress heightens attachment responses, this is also likely to have a significant impact on those who have no effective support figures and who have marked constraints on seeking effective help [3] making them more at risk for disorder at these crisis points.

Implications

Assessing severity of insecure style in addition to type of style is critical in understanding psychopathology outcomes. Only the ASI undertakes both. This analysis replicates a prior one in showing that individuals with mild levels of insecure style had no significantly increased risk of disorder. Those judged to have ‘mild’ levels of insecurity typically had good capacity to develop supportive close relationships, but held negative cognitions, denoting avoidance (mistrust, fear of rejection and high self-reliance) or anxious/ambivalence (high need for company, fear of separation and anger). In contrast those with highly insecure styles had both poor ability to relate and access support and displayed high such negative cognitions.

This study’s results provide evidence of specificity, albeit limited, regarding the associations between attachment styles and depression or anxiety disorder outcomes: Fearful and Angry-dismissive styles were the most consistently related to anxiety disorder. There was specificity found in the type of anxiety outcome, with Fearful Style significantly related to Social Anxiety and Angry-Dismissive style to GAD. Both of these styles incorporate socially avoidant characteristics, often associated with anxiety disorders: specifically Fearful individuals’ desire for closeness co-exists with fear of rejection, and the Angry-dismissive hostile rejection of others with avowed self-reliance. Fearful style has overt characteristics linked with socially anxious attitudes around fear of closeness and expectation of rejection. Interpretations of the evolution of the style revolve around the simultaneous negative view of the self and of others, whereby social interactions are marred by the perception of the self as unlovable and others as rejecting and devaluing of self [18]. Thus individuals with a high need for approval and avoidance of disapproval are argued to be more prone to social anxiety. As children, those with parents who demonstrate hostility, criticism, restrictiveness, coerciveness or lack of encouragement of skill development, who become fearful individuals develop expectations that social encounters readily result in relational devaluation, thus leading to social anxiety [12, 36].

The association between Angry-Dismissive style and GAD is less obvious. Key characteristics of this attachment style are avoidance as evidenced by over self-reliance, together with high levels of mistrust and anger towards others. The impact of the anger component has not yet been sufficiently investigated in the attachment literature. However, Bowlby viewed interpersonal anger as arising from frustrated attachment needs, functioning as a form of protest behaviour directed at regaining contact with the attachment figure [1]. A fundamental conclusion of attachment research on infants is that anger follows unmet attachment needs and that threats or separation from attachment figures produce powerful anger-related emotional responses such as terror, grief and rage (op cit). In response, chronic child frustration of attachment needs may lead to adult proneness to react with anger when relevant attachment cues are present thus linking both anger and anxiety states. Angry-dismissive styles may perpetuate characteristics of childhood anger related to threat of separation.

It is also important to consider why Angry-dismissive style does not relate to depression. Other studies have shown avoidant styles to be unrelated to depression, with the style reflecting a defence against strong emotion [2]. However, typically such studies have not differentiated Angry-dismissiveness from Withdrawn style, a distinction only made in the ASI. The latter is as expected, unrelated to any affective disorder in this analysis. It is more likely that the anger component of the former is protective in some degree against sadness and depression.

Linkages have been established between hostility and anxious attachment styles. A study encompassing 120 men with treatment referrals for wife assault [37] found Fearful attachment style associated with the constellation of verbal and physical abuse. Dutton and colleagues argue that fearfully attached men experienced high degrees of both chronic anxiety and anger. However, the classifications utilised in the study [18] provided no category for angry avoidant style but only for fearful avoidant style. It would be interesting to examine if the more abusive males in the series would in fact have been assessed as Angry-Dismissive in the ASI classification. Further research is required to understand the relationship between fear and anger in attachment, and its association with anxiety outcomes.

Strengths and applications

This study is useful in establishing highly insecure Fearful and Angry-Dismissive styles as vulnerability factors for new episodes of both anxiety disorders and major depression. Being able to determine these predictively provides a potential screening instrument for preventative interventions. Thus it may be possible to undertake preventative work with individuals whose attachment styles are assessed as highly insecure—perhaps in a series with previous episodes of disorder in order to prevent future relapse. Successful modification of such style may well be amenable to CBT or other psychotherapeutic techniques by focussing on behavioural and cognitive change around issues of closeness/avoidance and fear/anger in relationships. Modification of insecure attachment styles even to mild levels would be highly beneficial since these convey less risk of disorder.

The analysis of potentially mediating attachment styles (in the relationship between childhood adversity and adult disorder) provides the framework to infer causal pathways in development. Since not all individuals experiencing childhood adversity have increased risk of disorder, adult pathways perpetuating risk need to be identified. Given that the current analysis indicates only partial mediation, other concurrent factors need to be investigated in future research. Psychosocial stress models would indicate that low self-esteem, negative interaction with children, in addition to severe life events are likely to account for further mediation in a more holistic model and need more extensive investigation [25]. The mediating effects of attachment style between childhood adversity and adult disorder are crucial for understanding the nature of risk for affective disorder. As previous analyses have shown, childhood adversity is only associated with disorder in the minority of individuals – most survive in terms of adult psychopathology [38]. It is therefore necessary to identify those adult experiences through which risk is perpetuated so that well-timed interventions across the lifespan can be applied. This study has provided some stimulus to address such investigations in future research.

Notes

Compliance with original interview was 61%, with 22% refusal. The remaining 25% proved unsuitable in a paired sister-group subset because the sister proved unobtainable.

A proportion of the original sample were not contacted for follow-up, these included (a) the sisters of a subgroup recruited for validating the childhood information who lived outside the area (n = 98), and (b) a small group of the women with adult vulnerability (21) who did not have relatives suitable for study in the parallel inter-generational investigation. The numbers selected for follow-up therefore represented around half of the original series.

Withdrawn style had a modest association with depression, but this disappeared when controls were applied for disorder at interview 1.

References

Bowlby J (1973) Attachment and loss: vol 2. Separation: anxiety and anger, Basic Books, New York

Dozier M, Stovall KC, Albus KE (1999) Attachment and psychopathology in adulthood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR (eds) Handbook of attachment: theory, research, and clinical applications. The Guilford Press, New York, NY, USA, pp 497–519

Hammen CL, Burge D, Daley SE, Davila J, et al. (1995) Interpersonal attachment cognitions and prediction of symptomatic responses to interpersonal stress. J Abnormal Psychol 104:436–443

Eng W, Heimberg R, Hart T, Schneier F, Liebowitz M (2001) Attachment in individuals with social anxiety disorder: the relationship among adult attachment styles, social anxiety and depression. Emotion 4:365–380

Stein H, Koontz AD, Fonagy P, Allen JG, Fultz J, Brethour JR, Allen D, Evans RB (2002) Adult attachment: What are the underlying dimensions? Psychol Psychotherapy: Theory, Res Practice 75:77–91

Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR (1997) Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. J Personality Soc Psychol 73:1092–1106

Gerlsma C, Luteijn F (2000) Attachment style in the context of clinical and health psychology: a proposal for the assessment of valence, incongruence, and accessibility of attachment representations in various working models. Brit J Med Psychol 73:15–34

Murphy B, Bates GW (1997) Adult attachment style and vulnerability to depression. Personality Individual Diff 22:835–844

McCarthy G (1999) Attachment style and adult love relationships and friendships: A study of a group of women at risk of experiencing relationship difficulties. Brit J Med Psychol 1999 Sep 72(3):305 321

Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M (1996) The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification and response to psychotherapy. J Consulting Clin Psychol 64:22–31

Bifulco A, Moran PM, Ball C, Lillie A (2002c) Adult attachment style. II: its relationship to psychosocial depressive-vulnerability. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 37:60–67

Vertue, FM (2003) From adaptive emotion to dysfunction: an attachment perspective on social anxiety disorder. Personality Soc Psychol Rev, 7

Brown GW, Andrews B, Harris TO, Adler Z, Bridge L (1986) Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychol Med 16:813–831

Davidson J, Hughes D, George L, Blazer D (1993) The epidemiology of social phobia: findings from the Duke Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Psychol Med 23:709–718

Hart T, Turk C, Heimberg R, Liebowitz M (1999) Relation of marital status to social phobia severity. Depression Anxiety 10:28–32

Leary M, Kowalski R (1995) Social anxiety, Guilford, New York

Davila J, Beck JG (2002) Is social anxiety associated with impairment in close relationships? A preliminary investigation. Behav Therapy 33:427–446

Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM (1991) Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J Personality Soc Psychol 61:226–244

Rapee RM, Heimberg R (1997) A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Therapy 35:741–756

Bowlby J (1977) Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. Brit J Psychiatry 130:201–210

Whiffen VE, Judd ME, Aube JA (1999) Intimate relationships moderate the association between childhood sexual abuse and depression. J Interpersonal Violence 14:940–954

Bifulco A, Brown GW, Moran P, Ball C, Campbell C (1998) Predicting depression in women: The role of past and present vulnerability. Psychol Med 28:39–50

Brown GW, Harris TO (1993) Aetiology of anxiety and depressive disorders in an inner-city population: I. Early adversity. Psychol Med 23:143–154

Harkness KL, Wildes JE (2002) Childhood adversity and anxiety versus dysthymia co-morbidity in major depression. Psychol Med 32:1–11

Brown GW, Bifulco AT, Andrews B (1990) Self-esteem and depression: III. Aetiological issues. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 25:235–243

Cummings EM, Cicchetti, D (1990) Toward a transactional model of relations between attachment and depression. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM (eds) Attachment in the preschool years: theory, research, and intervention. University of Chicago

Rankin LB (2000) Mediators of attachment style, social support, and sense of belonging in predicting woman abuse by African American men. J Interpersonal Violence 15:1060–1080

Bifulco A, Moran PM, Ball C, Bernazzani O (2002b) Adult attachment style. I: its relationship to clinical depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 37:50–59

Bifulco A, Figueirido B, Guedeney N, Gorman L, Hayes S, Muzik M, Gatingny-Dally E, Valoriani VMK, Henshaw C (2004) Maternal attachment style and depression associated with childbirth: Preliminary results from a European/US cross-cultural study. Brit J Psychiatry (Special supplement) 184:31–37

Bifulco A, Brown GW, Lillie A, Jarvis J (1997) Memories of childhood neglect and abuse: corroboration in a series of sisters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:365–374

Bifulco A, Moran PM, Ball C, Jacobs C, Baines R, Bunn A, Cavagin J (2002a) Childhood adversity, parental vulnerability and disorder: examining inter-generational transmission of risk. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 43:1075–1086

Bifulco A, Brown GW, Harris TO (1994) Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA): A retrospective interview measure. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 35:1419–1435

First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer R, Williams G (1996) Users guide for SCID, Biometrics Research Division

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personality Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modelling, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York, London

Thompson R (2001) Childhood anxiety disorders from the perspective of emotion regulation and attachment. In: Vasey M, Dadds M (eds) The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 160–182

Dutton DG (1994) Intimacy-Anger and Insecure Attachment as Precursors of Abuse in Intimate Relationships. J Appl Soc Psychol 24:1367–1386

Bifulco A, Moran P (1998) Wednesday’s child: research into women’s experience of neglect and abuse in childhood and adult depression, Routledge, London, New York

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Medical Research Council (programme grant G9827201). Professor Kwon was released on sabbatical from Korea University, Seoul, South Korea to work in the team and conduct analyses. We acknowledge the important contribution of Professor George Brown and Tirril Harris to the research programme. We would like to thank Rebecca Baines, Bronwen Ball, Kate Benaim, Joanne Cavagin, Lucie Reader, Helen Rickard, Katherine Stanford and Lisa Steinberg for data collection. Thanks are also due to Dr. Soumitra Pathare for checking reliability of psychiatric ratings and to Laurence Letchford for computer analyses. Finally, we are grateful to the Islington families who generously, and patiently, participated in this research over the two waves of study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Logistic regression test of mediation: Highly Fearful or Angry-dismissive attachment style mediating the relationship between childhood neglect/ abuse and adult disorder.

Regression analyses | Predictor (IV) | Criterion (DV) | Exp(B)/SE | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Childhood Neglect/abuse | Anxiety or depression at follow-up interview | 2.09 (0.33) | 0.02 |

2 | Childhood Neglect/abuse | Highly Fearful or Angry-dismissive attachment style at interview 1 | 4.34 (0.40) | 0.0003 |

3 | Childhood Neglect/abuse | Anxiety or Depression at follow-up interview | 1.42 (0.36) | NS |

Highly Fearful or Angry-Dismissive attachment style | 4.95 (0.41) | 0.0001 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bifulco, A., Kwon, J., Jacobs, C. et al. Adult attachment style as mediator between childhood neglect/abuse and adult depression and anxiety. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 41, 796–805 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0101-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0101-z