Abstract

This study was conducted to compare attitudes of psychiatrists, other professionals, and laypeople towards compulsory admission and treatment of patients with schizophrenia in different European countries. Three case reports of patients with schizophrenia were presented to N=1,737 persons: 235 in England, 622 in Germany, 319 in Hungary, and 561 in Switzerland; 298 were psychiatrists, 687 other psychiatric or medical professionals, and 752 laypeople. The case reports presented typical clinical situations with refusal of consent to treatment (first episode and social withdrawal, recurrent episode and moderate danger to others and patient with multiple episodes and severe self-neglect). The participants were asked whether they would agree with compulsory admission and compulsory neuroleptic treatment. The rates of agreement varied between 50.8 and 92.1% across countries and between 41.1 and 93.6% across the different professional groups. In all countries, psychologists and social workers supported compulsory procedures significantly less than the psychiatrists who were in tune with laypeople and nurses. Country differences were highly significant showing more agreement with compulsion in Hungary and England and less in Germany and Switzerland (odds ratios up to 4.33). Own history of mental illness and having mentally ill relatives had no major impact on the decisions. Evidence suggests that compulsory procedures are based on traditions and personal attitudes to a considerable degree. Further research should provide empirical data and more definite criteria for indications of compulsive measures to achieve a common ethical framework for those critical decisions across Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The compulsory admission of patients in psychiatric hospitals and treatment against the patient’s will is seen as a legal and ethical problem requiring explicit criteria all over the world [6, 11, 14]. The World Health Organization emphasizes in its guidelines, actualized in the Declaration of Madrid [3]: “No treatment should be provided against the patient’s will, unless withholding treatment would endanger the life of the patient and/or of those who surround him or her. Treatment must always be in the best interest of the patient.” In clinical psychiatry, this concerns in the first instance patients with schizophrenia, in whom lack of insight and danger to self and others are frequent consequences of positive symptoms [18]. Among compulsorily admitted psychiatric inpatients, the most frequent diagnosis is schizophrenia [13]. Making decisions on compulsory admission and treatment, the psychiatrist on the one hand has to protect the patient’s autonomy, which requires the patient to give informed consent [9] and follows the principles of maleficence [first, do no harm (primum nihil nocere)] and beneficence (do good) [1]. On the other hand, there is the necessity to act in the “patient’s best interest” if there is a lack of capacity to give informed consent [9]. In cases of schizophrenia, this commonly means administering neuroleptic treatment. There is some evidence indicating that the way in which coercion is perceived by the patient has a major impact on the further course of the illness, even if controlled studies do not exist for ethical reasons [10]. Taking into account the desire to apply evidence-based decisions in all aspects of medicine, clear guidelines based on empirical evidence would be highly desirable for compulsory admission and treatment. However, until now, little is known about how psychiatrists decide in defined cases, whether they differ from public opinion about such cases and what influences their decisions. Within the last 5 years, two studies have been published, which examined public attitudes on compulsory psychiatric admission in representative population samples [8, 12]. Lauber et al. [7, 8] found in their Swiss study that about three quarters of people questioned supported the possibility of compulsory admission of mentally ill people. People with mentally ill family members or with own treatment experience did not differ in the rate of agreement.

Aims of the study

The aims of the present study were (1) to explore the attitudes of psychiatrists, other professionals and laypeople towards involuntary admission and treatment of people with symptoms of schizophrenia in characteristic scenarios and (2) to identify predictors of decisions. Different from the above-mentioned studies, we did not ask for general attitudes, but participants were asked for their decisions in clearly described clinical cases.

Materials and methods

Case reports (scenarios)

The three scenarios [19] were designed with the intention to represent characteristic stages and ethical conflicts in the course of the illness: first episode (scenario 1), first relapse (scenario 2) and multi-episode patient (scenario 3). The first and third scenario include details of moderate danger to the patient (without suicidal ideation), the second a moderate threat to others. The first scenario describes a 19-year-old man with a first episode of paranoid delusions, ideas of being poisoned and marked social withdrawal. The second case describes a 33-year-old woman with a first relapse of schizophrenia presenting disorganised thoughts, disordered, delusional and occasionally beating and threatening her elderly mother whom she lives with. The third scenario describes a 38-year-old man with multiple relapses of schizophrenia, now presenting with self-neglect, delusions, poor physical condition and social withdrawal. In all cases, it was pointed out that several attempts to provide treatment by outpatient services and by means of persuasion had failed. Aimed at laypeople, a “medical comment” was included in each case, explaining that from a doctor’s point of view, it was an evident case of schizophrenia and neuroleptic treatment could be assumed to be helpful. Finally, the respondents were asked in each case whether they would agree with (1) compulsory admission to a psychiatric hospital for a psychiatric examination and (2) compulsory neuroleptic treatment if the diagnosis of schizophrenia was confirmed. In scenario 3, respondents who had answered “no” to the question for treatment were asked whether they would change their mind if they received the following additional information: (a) without intervention, the patient would ruin himself financially, (b) the patient suffers from severe heart disease requiring treatment, (c) successful treatment would help to re-establish contacts with the patient’s relatives, and (d) previous treatment was successful and subsequently approved by the patient.

The scenarios were first written in German and then translated into English and Hungarian by the authors. Other persons experienced in both languages checked the quality of the translation. Inasmuch as the Swiss study was conducted only in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, the German version was applied. The English version is attached as Appendix A.

Samples

The German sample was recruited from all over Germany by placing an advertisement in the most widespread German medical journal (Deutsches Ärzteblatt). Interested colleagues received the scenarios by post, fax or e-mail and were asked to distribute the questionnaire with the scenarios among doctors, other professionals and laypeople. Most of the included persons work in psychiatric hospitals.

The English sample was recruited in the northwest of England. The health professionals were recruited by direct distribution of the questionnaires at medical meetings and onwards; laypeople were recruited via GP practices.

The Swiss sample was recruited among six psychiatric hospitals in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. The hospitals’ directors supported the project actively and asked employees of different professions to fill in the questionnaire and to recruit interested laypeople.

The Hungarian version was presented first at the Hungarian National Psychiatric Congress. Interested psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers and nurses distributed the scenarios and questionnaires both among professionals of psychiatric hospitals in Budapest and other cities and among medical students and patients’ relatives.

Statistical methods

We calculated logistic regression models for each of the six questions asked, respectively (three scenarios, decisions for involuntary admission and involuntary treatment). Dichotomous outcome (yes/no) was used as a dependent variable. Country, profession, gender, age, mental illness in the family (yes/no) and own history of mental illness (yes/no) were used as independent variables. Odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals were calculated for each predictor. Results are supposed to be significant if the confidence intervals do not include “1.” An OR significantly >1 means that the respective variable increases the probability of a “yes” decision in the respective question by the factor of the OR and vice versa for ORs<1. Deliberately, as reference (OR=1), “Switzerland” was determined among countries and “psychiatrists” among professions. The logistic regression analyses were performed using the program SAS.

Results

The numbers of included persons in the different countries, their professions and further sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. The group of laypeople included relatives, medical students and other people. The proportion of participants with mental illness in the family was higher than expected not only among laypeople but also among professionals. This might indicate some skewing in the selection process in that affected people might have been more likely to participate in such a study than people without contact with mental illness. No significant differences in decisions were found between subgroups of laypeople.

The rates of agreement with compulsory admission and treatment in the three scenarios are shown in Tables 2, 3, 4, as distributed in the four countries, the different professional groups, and among people with mentally ill members in own family and with own history of mental illness (which occurred in all professional groups). The percentages of “yes” decisions (agreement) are shown for admission and treatment (in bold) in the three scenarios. In scenario 3, we had asked people who did not agree with compulsory neuroleptic treatment whether they would change their mind if they received additional information (1) that the patient was going to ruin himself financially without intervention, (2) that the patient suffered from a severe heart disease, (3) that treatment would offer the possibility of revitalising contacts with his family, and (4) that the patient had accepted treatment previously and had subsequently improved. The increase in agreement to compulsory treatment under the respective circumstances is shown in Table 4.

Table 5 shows significant predictors of agreement to compulsory admission and compulsory neuroleptic treatment in the three scenarios and the respective OR and confidence intervals as calculated by a multiple logistic regression model. Significance was reported if the confidence intervals did not contain “1.”

Discussion

We received the opinions of 1,737 persons, among them were 298 psychiatrists, in four European countries about compulsory admission and treatment referring to the three case reports of patients with schizophrenia. These case reports were designed as “borderline” cases provoking discussion on patients’ autonomy on the one hand and paternalistic treatment to avoid harm to the patient (scenarios 1 and 3) or others (scenario 2) on the other hand. The principal results were as follows:

-

(1)

Even in these “borderline” cases, a broad majority (between 59 and 87%) of participants agreed with compulsory admission and treatment. Lauber et al. [8] reported a similar result with a positive attitude towards compulsory admission in over 70% of their respondents. An important difference is that these authors did a survey regarding compulsory admission, in general, although we had presented concrete case reports, which were designed to be ambiguous with respect to danger to self and others. In the case of only moderate danger to others (scenario 2), the agreement was clearly higher than in the other two scenarios (87.5%). The agreement was moderately lower in scenario 3, where an urgent need for treatment without immediate danger to self or others was suggested, but increased to 78% if the additional information was available that medication had previously been accepted.

-

(2)

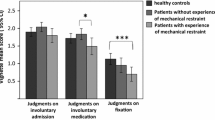

There was a lower acceptance of compulsory measures among social workers and psychologists over all cases and countries. Psychiatrists were remarkably in tune with other physicians as well as nurses and the heterogeneous group of laypeople. Only the case of moderate danger to others (scenario 2) divided the groups more significantly depending on their position: Psychiatrists supported compulsory admission with about fivefold probability compared to psychologists and social workers and about threefold probability compared to laypeople. However, people with mental illness in their own family supported compulsory admission even more than psychiatrists, independent from professional status. In contrast, people with a history of mental illness less frequently supported compulsory admission in this scenario. The scepticism of social workers could be observed in all countries, although there are differences in their function within the admission procedure in the different countries. England is the only one of the four countries where social workers are involved in the legal procedure of compulsory admission [15]. In a survey in Switzerland, laypeople agreed significantly less with the possibility of involuntary admission than psychiatrists (72 vs 99%) [23]. However, this difference could not be observed in our investigation where concrete case reports were presented. People’s attitudes towards aspects of compulsory treatment might depend on whether they can imagine a real-life scenario.

-

(3)

Personal experiences such as having a family member with mental illness and own history of mental illness generally played a minor role in the decisions. Only in the case of danger to others (scenario 2) compulsory admission was significantly more supported by relatives of mentally ill patients and less by persons with a history of own mental illness.

-

(4)

Gender and age were moderate predictors. Females supported compulsion more frequently. This finding could be interpreted as a higher desire for security or as a more paternalistic attitude. Similar, but weaker findings were reported by Lauber et al. [7]. In contrast to their findings, agreement with compulsion increased with age in our study.

-

(5)

The strongest predictor in three of the six decisions asked for, however, was the country where the person lived. Despite not reaching significance in all cases, the tendency was the same for all decisions: highest support of compulsory measures in Hungary, followed by England, clearly less support in Germany and least in Switzerland. The national differences in attitudes are certainly determined by a variety of factors, and we can only speculate on some of them. The concerns about a misuse of psychiatry could be higher in Germany for historical reasons [15]. Having been the nucleus of free Switzerland, the German-speaking part of Switzerland has had a very strong tradition and identity of freedom and autonomy for historical reasons even more than the French and Italian part. Actually, support of compulsory admission was significantly lower in the German part than in the Italian and French part in the survey by Lauber et al. [7]. In Hungary, paternalistic and custodial attitudes are possibly more prevalent, although there is a widespread distance and suspicion towards psychiatric hospitals. The latter might be the reason why, in Hungary, more people supported involuntary medication than involuntary admission. Without the experience of totalitarian dictatorship and abuse, England chooses a very pragmatic approach towards involuntary hospitalisation and treatment assuming that experts and relatives act benevolently in the patient’s interest, as outlined by Röttgers and Lepping [16].

In England, there is high public concern about danger to the public by the mentally ill patients, a concern largely fostered by the mass media [4]. This could be exaggerated by automatic inquiries of all suicides and homicides committed by mentally ill patients. Furthermore, treating psychiatrists have a very high level of personal responsibility for the care of their patients compared to other countries, which may influence decision making and the tendency to detain [15]. Detention rates have risen within the last years and seem to be higher than in other European countries [22] despite a relatively low number of psychiatric beds per inhabitant.

The major limitation of this study is sample selection bias. The samples of the respective countries are not completely comparable with respect to age, percentage of professional groups and personal experience. Moreover, the sampling process was not identical in the four countries and depended on personal contacts of the authors. There is a tendency that people with personal interest and experiences in the issue are overrepresented in our sample, which is indicated by the high proportion of people with “mentally ill members in their own family” in all groups. In all four countries, people from multiple locations and professions could be included. However, the samples cannot claim to be representative for the respective group, and thus, this study is of exploratory character. Its strength is that it does not refer to an abstract process such as “compulsory admission,” in general, but compares attitudes among different countries and professions with regard to well-described clinical cases. Further research should promote ethically sound decision making supported by empirical data on how decisions for or against compulsory treatment influences the course of illness. Although the effects of involuntary outpatient commitment have been evaluated by well-designed randomized trials within the last years [2, 20, 21], until now, there are almost no scientifically sound studies addressing the outcome of coercive inpatient treatment [5, 17].

References

Beauchamp T, Childress J (2001) Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS (2003) Effects of legal mechanisms on perceived coercion and treatment adherence among persons with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 191:629–637

Helmchen H (1998) Die Deklaration von Madrid 1996. Nervenarzt 69:454–455

Holloway F, Szmukler G (1999) Public policy and mental health legislation should be reconsidered. BMJ 318:1354

Høyer G (2000) On the justification for civil commitment. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 399:65–71

Isohanni M, Nieminen P, Moring J, Pylkkänen K, Spalding M (1991) The dilemma of civil rights versus the right to treatment: questionable involuntary admissions to a mental hospital. Acta Psychiatr Scand 83:256–261

Lauber C, Falcato L, Rössler W (2000) Attitudes to compulsory admission in psychiatry. Lancet 355:2080

Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, Rössler W (2002) Public attitude to compulsory admission of mentally ill people. Acta Psychiatr Scand 105:385–389

Lepping P (2003) An ethical review of consent in medicine. Psychol Bull 27:285–290

Lidz CW, Hoge SK, Gardner W, Bennett NS, Monahan J, Mulvey EP, Roth LH (1995) Perceived coercion in mental hospital admission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:1034–1039

Olofsson B, Jacobsson L, Gilje F, Norberg A (1999) Being in conflict: physician’s experience with using coercion in psychiatric care. Nord J Psychiatry 53:203–210

Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, Stueve A, Kikuzawa S (1999) The public’s view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. Am J Publ Health 89:1339–1345

Riecher A, Rössler W, Löffler W, Fätkenheuer B (1991) Factors influencing compulsory admission of psychiatric patients. Psychol Med 21:197–208

Rosenman S (1998) Psychiatrists and compulsion: a map of ethics. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 32:785–793

Röttgers HR, Lepping P (1999a) Zwangsunterbringung und -behandlung psychisch Kranker in Großbritannien und Deutschland. Psychiatr Prax 26:139–142

Röttgers HR, Lepping P (1999b) Treatment of the mentally ill in the Federal Republic of Germany. Psychol Bull 23:601–603

Steinert T, Schmid P (2004) Outcome is not dependent on voluntariness of treatment in inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 55:786–791

Steinert T, Wiebe C, Gebhardt RP (1999) Aggressive behavior against self and others among first-admission patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 50:85–90

Steinert T, Hinüber W, Arenz D, Röttgers HR, Biller N, Gebhardt RP (2001) Ethische Konflikte bei der Zwangsbehandlung schizophrener Patienten. Entscheidungsverhalten und Einflussfaktoren an drei prototypischen Fallbeispielen. Nervenarzt 72:700–708

Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Burns BJ (2003) Effects of involuntary outpatient commitment on subjective quality of life in persons with severe mental illness. Behav Sci Law 21:473–491

Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Hiday VA (2001) Effects of involuntary outpatient commitment and depot antipsychotics on treatment adherence in persons with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 189:583–592

Zinkler M, Priebe S (2002) Detention of the mentally ill in Europe—a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand 106:3–8

Zogg H, Lauber C, Ajdacic-Gross V, Rössler W (2003) Einstellung von Experten und Laien gegenüber negativen Sanktionen bei psychisch. Kranken. Psychiatr Prax 30:379–383

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Questions to the interviewed person are listed here only for scenario 3

Scenario 1

The parents of a 19-year-old man are concerned about the way in which their son has changed over the past 6 months. Half a year ago, he successfully passed his ‘A’ levels with good marks, he had several hobbies that he pursued, and he had friends and, at times, also a girlfriend.

Since then, he has started to isolate himself, and he spends a lot of time in his room, having locked himself into it. Initially, he had tried to find a job but he has given this up now. He has also given up his hobbies and hardly sees his friends any more. During the daytime, he mostly keeps his windows closed and the blinds down. At night, his parents noticed that he keeps the light on and paces up and down in his room. He has become hostile towards his parents. He appears suspicious towards them and talks as little as possible. Furthermore, he suspiciously checks the food that his mother prepares for him, only eats it in his room and has even mentioned fears that the food may be poisoned. He has lost a significant amount of weight, however, not to an extent where his health would obviously be at risk. There is no evidence of suicidal thoughts or aggressive behaviour towards others. There is no evidence of alcohol or drug misuse, either. Over the last few months, his parents and the community psychiatric nurse, whom his GP involved, have made several attempts to persuade him to be treated by a psychiatrist, but these attempts have all failed.

Scenario 2

A 33-year-old single translator suffered from an acute phase of schizophrenia 3 years ago and needed to be treated in hospital. With the help of medication and psychosocial intervention, she became free of symptoms, was discharged from hospital and returned to work. Her psychiatrist prescribed her medication to prevent a relapse, but 9 months after her discharge from hospital, she stopped all her medication because she felt so well. Three months later, she resigned from her job because of conflict with colleagues at work. She now lives with her 74-year-old mother again. Their relationship has always been close but difficult. Last year, this led to increasing tensions, which led to the patient ordering her mother around in an inappropriate manner and even hitting her on several occasions. When talking to the GP, she stated that she had to hit her mother because she would not obey her. At the time, she appeared agitated, her speech was incoherent, it was not always possible to follow what she was saying and she had religious delusions. There was no other evidence of suicidal ideas or aggression towards others. At the time, the patient appeared well kempt, and the apartment was very clean and orderly. When the GP put to the patient that she might have become ill again, she called this a “ridiculous suggestion.” She refused to be admitted to a hospital or to take the medication that she used to take after her first hospital admission. Other relatives and her community psychiatric nurse tried in vain to persuade her to seek help. Her mother appeared scared and helpless when the GP visited them.

Scenario 3

A 38-year-old trained mechanic, divorced 10 years ago, has been living on Disability Living Allowance for the last 5 years. He no longer has any contact with his ex-wife or family, his parents are dead and he has no siblings. Seven years ago, he became ill with schizophrenia for the first time. Since then, he had to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital three times, the last time being 4 years ago. Whenever he was ill, he heard voices, and he believed that he was being persecuted by organised criminals and alien powers. Furthermore, he consumed huge quantities of alcohol to cope with his anxieties. After treatment with anti-psychotic medication and psychosocial intervention, his delusions and hallucinations disappeared, but he was left with a certain apathy and loss of interest. Three years ago, the patient stopped all treatment and contact with psychiatric services. He would not see his GP or psychiatrist any more, and he also stopped taking medication. He still lived in his own flat but stopped all contact with friends and acquaintances, and he ceased to pursue his hobbies. He only rarely left his flat to buy food, but he solely ate bread and tinned food. He began to become very suspicious towards other people; he increasingly appeared unkempt and neglected, with his hair and beard growing unattended and his clothes unwashed and shabby. When other people in the house alarmed Social Services, they found his flat in a very bad and neglected condition, with heaps of papers, empty tins and other rubbish piled high. It was, however, difficult to prove that there was any direct risk to his health by eating unhygienic food. There were no reports of suicide attempts, deliberate self-harm or aggression towards others. Judging by the beer bottles lying around, he appeared to be drinking on a regular basis but not in extreme quantities. The patient declared that he was not willing to be assessed or treated or take any prescribed medication. His speech was slightly incoherent and he appeared quite hostile. He hinted towards evil powers that were responsible for the dismal state that the world was in and who were after him. There were several visits from community psychiatric nurses, psychiatrists and social workers, but he always refused any help.

Would you want this man to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital and his flat be cleaned and made hygienic even against his will? If you have said “no,” would you change your mind if:

-

(a)

There were serious threats to the patient’s independence and finances, with his illness deteriorating further, e.g. loss of his flat because of unpaid rent.

-

(b)

There were significant medical dangers should he be left to himself, e.g. an existing heart disease for which he would refuse treatment.

-

(c)

You discovered that the patient’s children would be interested in contacting him again should he be able to give up his suspicion against them, which is probably due to his illness.

-

(d)

You discovered that, when the patient was last treated in hospital, he was only treated against his will for a few days but then accepted treatment voluntarily and continued to take his medication independently.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steinert, T., Lepping, P., Baranyai, R. et al. Compulsory admission and treatment in schizophrenia. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 40, 635–641 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0929-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0929-7