Abstract

Background

Numerous studies have established proof of selective media reporting about the mentally ill, with the majority of the reports focusing almost exclusively on violence and dangerousness. A handful of studies found that there is an association between negative media portrayals and negative attitudes toward people with mental illness. However, empirical evidence of the impact of newspaper reports about mentally ill people on readers’ attitudes is very scarce.

Aims

To examine the impact of a newspaper article linking mentally ill persons with violent crime and the impact of an article providing factual information about schizophrenia on students’ attitudes toward people with mental illness.

Method

A total of 167 students aged 13–18 years were randomly assigned one of two articles. A period of 1 week before and 3 weeks after reading the newspaper article, they were asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of their attitudes toward mentally ill people.

Results

Respondents who read the article linking mentally ill persons with violent crime displayed an increased likelihood to describe a mentally ill person as dangerous and violent. Conversely, respondents who read the informative article used terms like ‘violent’ or ‘dangerous’ less frequently. The desire for social distance remained virtually unchanged at follow-up in both groups.

Conclusion

Two potential approaches to break the unwanted link between negative media reporting and negative attitudes are suggested. First, an appeal to media professionals to report accurate representations of mental illness. And second, an appeal to the adults living and working with adolescents to provide opportunities to discuss and reflect on media contents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to Hayward and Bright [1], dangerousness is one of the four main conceptions about mentally ill people, which the stereotype of mental illness is comprised of. A recent population survey in Germany found that the notion that most sex crimes are committed by people with schizophrenia and that people with schizophrenia commit particularly violent crimes was met with approval by one-fifth of the respondents, just half as many as those who disagreed with this view. Moreover, the opinion that people with schizophrenia are a great danger for little children was even endorsed by over one-third of the respondents [2]. The reasons for these misconceptions are manifold. However, there is evidence that the media may play a part in creating and reinforcing the public perception that mentally ill people are violent and dangerous.

As early as 1957, Nunnally found that the media provide an inaccurate image of mental illness. Over 40 years later, in their overview of international studies on the portrayal of mental health and illness in the media, Francis et al. [3] draw a similar conclusion by stating that (a) mental illness is portrayed negatively in the mass media, (b) media presentations of mental illness promote negative images and stereotypes, (c) there is a strong link between mental illness and violence in media messages and (d) stories associating mental illness with violence and crime were given greater prominence than positive items about mental illness. When assuming that the media are the public’s most significant source of information about mental illness [4], this one-sided, selective reporting might result in the formation of negative attitudes or at least reinforce negative stereotypes about people with mental illness as has been shown by Angermeyer and Matschinger [5]. A handful of studies investigating the association between media portrayals of mental illness and attitudes of a given population group in a given time (e.g., 6, 7, 8) have indeed found a link between negative media portrayals and negative attitudes toward people with mental illness.

To our knowledge, Thornton and Wahl’s experimental study [8] is the only one assessing directly the impact of a newspaper article depicting a violent murder committed by a mentally ill person and the effect of corrective information on the attitudes of readers of such an article. They found that only those reading the article without first being provided with corrective information expressed harsher attitudes toward people with mental illness than participants who either were exposed to corrective information prior to reading the article or who read an article unrelated to mental illness. The authors concluded that negative media reports contribute to negative attitudes toward people with mental illness, and that corrective information may be effective in mitigating the impact of these negative reports. However, since in this study attitudes were not measured prior to reading the article the findings remain somewhat inconclusive.

Therefore, we set out to carry out a new study on the impact of newspaper reports about violent crimes committed by mentally ill people on attitudes toward the mentally ill, this time using a randomized controlled trial with assessments of attitudes prior to the exposure to the reports and at follow-up. The target group was composed of grammar and secondary school students aged 13–18 years. The rationale for choosing this particular group was that younger children do not yet have a clear idea of what mental illness means [9] or what specific characteristics are associated with it and that explicit conceptions of personality traits which are the basis for the formation of stereotypes about groups of people are not developed until adolescence [10]. Therefore, their ideas, conceptions and attitudes can still be influenced, both positively and negatively. Based on the aforementioned findings, our hypothesis was that students who read an article reporting about violent crimes committed by mentally ill people would show an increase in negative attitudes toward these people as compared with students who read an article containing correct information about schizophrenia.

Methods

Procedure and sample

The participants in this study were students enrolled at six different grammar schools and secondary schools in Leipzig, Germany. A parental consent form sought the consent of both parents and students, allowing them to opt either in or out of the study. A total of 206 students agreed to participate in the study. Baseline assessment of students’ attitudes was carried out one week before exposure to the journal article. Each participant was then randomly assigned one of two articles. The first article was a combination of two actual newspaper clippings, with the first reporting about a 19-year-old defendant who had raped and committed an attempted murder on a 7-year-old first-grader (“Prison and psychiatric ward for rapist”). The second newspaper report was titled “Double murder after escape from psychiatric hospital”, in which a 27-year-old man stabbed his older sister and her partner to death after escaping from a psychiatric hospital. The two clippings linked a person with a mental illness with violent, dangerous, unpredictable, aggressive and irrational behaviour and established that the public has reason to fear people with mental illness, even their own relatives or family members. We will call this article the negative article in this paper. The second newspaper article discussed misconceptions about mental illness and provided correct information, including facts regarding the development and the course of schizophrenia. This article will be called the informative article. In total, 103 students each were presented with the negative or the informative article. Students’ attitudes were measured again 3 weeks after reading the article. Among the students assigned to the negative article 28 did either not read the article or did not participate in the follow-up assessment, while among those assigned to the informative article there were only 11 drop-outs. Only students with complete data sets were included into the analysis, i.e., 75 students who read the negative article and 92 students who read the informative article. As shown in Table 1, more female students and students who never read a newspaper had been allocated to the group exposed to the informative article. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with regard to age, reading a magazine or watching TV.

Instruments

At baseline and follow-up, students’ attitudes toward people with mental illness were assessed by means of a self-administered questionnaire containing an open-ended question about assumed characteristics of mentally ill people and ten items enquiring into students’ desire for social distance toward mentally ill people. The item list that had been previously utilized in another study on students’ attitudes toward people with schizophrenia [9] was slightly modified for the purpose of this study. Using a five-point Likert scale, respondents could express their willingness or reluctance to accept someone with schizophrenia in a given social relationship. The scores of the 10 items were summed up in a sum score, with higher scores reflecting more socially rejecting attitudes. The internal consistency of the scale, measured by means of Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.68 at baseline and 0.79 at follow-up. In addition, socio-demographic characteristics and media consumption were assessed at baseline.

All responses to the open-ended questions were categorized to generate preliminary categories into which responses with similar meaning were combined. In a consensus-building discussion [11], these categories were differentiated, combined, and revised several times, with unclear classifications and overlaps being discussed by the research team. According to this principle, a set of 14 categories for mentally ill people (“crazy”, “disabled”, “normal”, “distraught, confused”, “dangerous, violent”, “ill, unstable”, “low intelligence”, “low ethical decision-making ability”, “lack of or uneasy interaction with others”, “lack of acting in a responsible manner”, “no dreams and goals in life”, “low self-confidence”, “lack of independence” and “others”) was gradually constructed, which allowed the assignment of all responses given by the students. For the purpose of this study, the focus will be on the category “dangerous, violent”.

Statistical methods

In order to test the effect of the different articles on the alteration of attitudes, two hierarchical nested cross-sectional time series models were estimated using a generalized least squares (GSL) model for social distance [12] and a random effects logit model for the explanation of the dangerous/violent attribute [13, 14]. These models allow for a likelihood ratio test for the effect of time, article and the interaction of interest.

Results

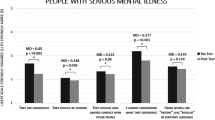

While at baseline, 32% of the students who read the negative article used terms like ‘violent’ and ‘dangerous’ to describe a mentally ill person, at follow-up this number increased to 54.7%. Of the students who read the informative article, 26% at baseline and 13% at follow-up used these terms to describe a mentally ill person. In the random effects logit model, the association between respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, type of article and time on one hand, and the description of a mentally ill person as dangerous and violent on the other was analysed (Table 2). No effect was found for gender, age and media consumption. Effects were found for time and the interaction between time and article. Prior to reading one of the two articles, the likelihood to describe a mentally ill person as dangerous and violent was the same for all study participants. Looking at the interaction term between time and article, the likelihood to describe a mentally ill person by using words that can be assigned to the category ‘dangerous, violent’ increases for those participants who read the negative article. The likelihood ratio test clearly shows that the parameters time, article and interaction contribute highly significantly to the fit of the model (LR χ2 = 33.28).

While at baseline, the mean social distance of all respondents who read the negative article was 25.0 (SD 0.68) it was 26.0 (SD 0.79) at follow-up. The figures for those who read the informative article were 24.9 (SD 0.63) at baseline and 24.3 (SD 0.70) at follow-up. In the GLS model, the association between respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, type of article and time on the one hand, and the desire for social distance on the other was calculated (Table 3). No significant effect for article, time and their interaction term can be found as shown also by the non-significant likelihood ratio test (LR χ2 = 2.21). The desire for social distance decreases with increasing age. Female students tended to express less desire for social distance than male students. And there was also a trend toward an increased desire for social distance among those who watch TV more frequently.

Discussion

Our hypothesis that students who read the negative article will express more negative attitudes toward people with mental illness was in part supported by our findings. As expected, these students displayed an increased likelihood to describe a mentally ill person as dangerous or violent. By contrast, students who read the informative article used terms like “violent” or “dangerous” less frequently. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was virtually no change as concerns the desire for social distance. This holds true for students who read the negative article as well as for those who read the informative article.

How come that there was a significant change of the stereotype about people with mental illness while the desire for social distance remained practically unchanged? Among the various theoretical conceptualizations (e.g., theory of social representations: 15–17) the notion of the “stigma process” [18] seems particularly suitable for explaining this phenomenon. According to the authors the various stigma components can be conceived of as being arranged in a logical order with stereotypes coming first and discrimination, in our study measured by the desire for social distance, second. This sequence may also be reflected in our findings. The exposure to the articles may first affect the stereotypes held by students, i.e., the cognitive stigma component, before the desire for social distance, i.e., their behavioural intentions, will also be changed. This matches Schulze et al.’s findings [9], which also found that it is easier to change stereotypes than behavioural intentions. While in their study, a school project helped to change attitudes for the positive, our study indicates that the change also works in the opposite direction, toward more negative attitudes.

The trend we have found toward an increased desire for social distance among students with a higher TV consumption ties in with findings of other studies. As a recent study from Germany discovered, the desire for social distance among adults toward people with schizophrenia increases almost continuously with their TV consumption (Angermeyer et al. in press). Granello and Pauley’s study from the US (2000) also revealed that the number of hours of television watched per week was significantly and positively related to intolerance.

The findings of this study have to be considered in the light of research on media effects in general. The multitude of theories that have been proposed, such as the two-step flow of communication theory [19], the knowledge gap hypothesis [20], the agenda-setting approach [21], the uses-and-gratifications approach [22] or the spiral of silence theory [23], document the complexity of this research area. Simple stimulus-response models as used in our study can certainly only capture some aspects of how the media can affect people’s attitudes. Although an advantage of the experimental design used in our study is that the content of the stimulus can be kept under control, the participants have to focus on this stimulus and the influence of other intervening factors can be excluded; its disadvantage is that we created a situation, which has little in common with reality, where people are exposed to numerous stimuli that may attract more attention than the information on people with mental illness. In other words, while the internal validity of our experiment is rather high, its external validity is quite limited [24, 25]. In addition, 26% of the students never read a newspaper and 43% only 1–2 times a week, while they also encounter a multitude of information from other media sources, e.g., TV or magazines (Table 1). Despite these reservations we think that it is legitimate to claim that we were able to demonstrate that information in newspaper articles on people with mental illness has the potential of impacting attitudes. However, to what extent this may happen in reality remains an open question that can only be answered based on data from a naturalistic study. A further limitation of this study is that we cannot say how long the effect on students’ perceptions of mentally ill people may have persisted since the only follow-up was conducted after a time period of 3 weeks. In our view, the exposure to one single article will certainly not suffice to influence attitudes persistently. This may need the exposure to a series of articles with similar content over a longer period of time [26].

Two potential approaches to prevent that negative stereotypes about persons with mental illness are generated or reinforced by the media can be derived from stimulus-response theory, which served us as conceptual framework. First, a simple but straightforward message to the media and media professionals: STOP reporting inaccurate representations of mental illness [27]. There have been first efforts to provide guidelines, codes and issues for media professionals to consider when reporting about mental illness, e.g., 28. And there are first signs of light of hope on the media horizon. A recent study found that media reporting of mental illness was extensive, generally of good quality and focused less on themes of crime and violence [29]. As the findings of our study suggest, informative reporting can pull respondents’ attitudes toward more favourable views. Thus, we need a more balanced reporting in the media. Although this may not be achieved easily [30], it is certainly worth the effort. The second approach involves parents, teachers, social workers and all other adults living or working with adolescents. If we cannot change the way the media reports about mental illness, we can at least try to influence how adolescents assimilate and interpret media messages by giving them opportunities to discuss and reflect on media contents. An excellent example of how this can be accomplished is the school project “Crazy? So what!” [9], which, among others, challenges media messages about mentally ill people (for more information see http://www.irrsinnig-menschlich.de).

References

Hayward P, Bright J (1997) Stigma and mental illness: A review and critique. J Ment Health 6:345–354

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (2004) The stereotype of schizophrenia and its impact on the discrimination of people with schizophrenia: Results from a representative survey in Germany. Schizophr Bull 30:1049–1061

Francis C, Pirkis J, Dunt D, Blood RW (2001) Mental health and illness in the media: A review of the literature. Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing Canberra

Coverdale J, Nairn R, Claasen D (2002) Depictions of mental illness in print media: a prospective national sample. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 36:697–700

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (1996) The effect of violent attacks by schizophrenic persons on the attitude of the public towards the mentally ill. Soc Sci Med 43:1721–1728

Domino G (1983) Impact of the film, “One flew over the cuckoo’s nest”, on attitudes towards mental illness. Psychol Rep 53:179–182

Wahl OF, Lefkowits JY (1989) Impact of a television film on attitudes toward mental illness. Am J Community Psychol 17:521–8

Thornton JA, Wahl OF (1996) Impact of a newspaper article on attitudes toward mental illness. J Community Psychol 24:17–25

Schulze B, Richter-Werling M, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2003) Crazy? So what! Effects of a school project on students’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiat Scand 107:142–150

Flavell JH, Miller PH, Miller SA (2001) Cognitive development. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs NJ

Mruck K, Mey G (1998) Selbstreflexivität und Subjektivität im Auswertungsprozess biographischer Materialien. Zum Konzept einer Projektwerkstatt qualitativen Arbeitens zwischen Colloquium, Supervision und Interpretationsgemeinschaft. In: Jüttermann G, Thomae H (eds) Biographische Methoden in den Humanwissenschaften. Psychologie Verlags Union, Weinheim, pp 284–306

Greene WH (2003) Econometric analysis. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs NJ

Diggle R, Liang P, Zeger S (1994) Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Liang P, Zeger S (1986) Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73:13–22

Herzlich C, Pieret J (1984) Malade d’hier, malade d’aujourd’hui: de la mort collective au devoir de guérison. Payot, Paris

Jodelet D (1989) Folies et représentations sociales. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

Hoffmann-Richter (2000) Psychiatrie in der Zeitung. Psychiatrie-Verlag, Bonn

Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L (1997) On stigma and its consequences: Evidence from a longitudinal study of patients with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav 38:117–190

Lazarsfeld PF, Berelson B, Gaudet H (1944) The people’s choice. New York

Titchenor P, Donohue GA, Olien CN (1970) Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public Opin Quart 34:159–170

McCombs ME, Shaw DL (1972) The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin Quart 36:176–187

Blumler JG, Katz E (eds) (1974) The uses of mass communications. Current perspectives in gratification research. Beverly Hills

Noelle-Neumann E (1974) Die Schweigespirale. Über die Entstehung der öffentlichen Meinung. In: Forsthoff E, Hörstel R (eds) Standorte im Zeitstrom. Festschrift für Arnold Gehlen Frankfurt a.M

Merten K (1994) Wirkungen der Medien. In: Merten K, Schmidt SJ, Weischenberg S (eds) Die Wirklichkeit der Medien. Westdeutscher Verlag, Weinheim pp 291–328

Bonfadelli H (2004) Medienwirkungsforschung I. UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, Konstanz

Bock M (1990) Medienwirkung aus psychologischer Sicht: Aufmerksamkeit und Interesse, Verstehen und Behalten, Emotionen und Einstellungen. In: Mentsch D, Freund B (eds) Fernsehjournalismus und die Wissenschaften. Westdeutscher Verlag Opladen

Corrigan PW (2004) Don’t call me nuts: an international perspective on the stigma of mental illness. Acta Psychiat Scand 109:403–404

Mindframe Media and Mental Health Project (2004) Reporting suicide and mental illness. A resource for media professionals. Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra

Francis C, Pirkis J, Blood RW, Dunt D, Burgess P, Morley B, Stewart A, Putnis P (2004) The portrayal of mental health and illness in Australian non-fiction media. Aust NZ J Psychiat 38:541–546

Stuart H (2003) Stigma and the daily news: Evaluation of a newspaper intervention. Can J Psychiat 48:651–656

Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S, Pott D, Matschinger H (2005) Media consumption and desire for social distance towards people with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 20:246–250

Granello DH, Pauley PS (2000) Television viewing habits and their relationship to tolerance toward people with mental illness. J Ment Health Counseling 22(2):162–175

Nunnally J (1957) The communication of mental health information: a comparison of the opinions of experts and the public with mass media presentations. Behav Sci 2:222–30

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dietrich, S., Heider, D., Matschinger, H. et al. Influence of newspaper reporting on adolescents’ attitudes toward people with mental illness. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 41, 318–322 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0026-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0026-y