Abstract

Background

Research on the association of psychopathology and violence has mainly focused on severe but rare mental disorders, especially psychotic disorders. However, evidence is growing that psychotic disorders are continuous with common psychotic-like experiences in the general population. This study aimed to examine the association of psychotic-like experiences with violence in a general population sample.

Methods

In 38,132 adult participants of the 2001 US National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, the association of psychotic-like experiences with violent behavior were examined.

Results

Psychotic-like experiences were reported by 5.1% (N = 2,584) of adults in the community. These experiences were associated with increased risk of attacking someone with the intent of hurting that person (Odds Ratio [OR] = 5.72), intimate partner violence (OR = 4.97), arrests for aggravated assault (OR = 5.12), and arrests for other assault (OR = 3.65). The risk of violence increased with the number of psychotic-like experiences. Unusual perceptual experiences and paranoid ideations were more consistently associated with violence.

Conclusions

The link between psychopathology and interpersonal violence appears to expand beyond the limits of severe mental disorders and to include more common psychotic-like experiences in the general population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Past research on the association of mental health problems and violent behavior has focused mainly on individuals with severe mental disorders and especially psychotic disorders in treatment settings [1–3]. Little is known about the contribution of the more common, but less severe psychotic experiences in the community [4, 5]. Recent studies suggest that psychotic symptoms in clinical samples are better characterized by continuous dimensions rather than discrete categories [6] and that self-reported psychotic experiences in general population samples are on a continuum with psychotic symptoms in clinical samples [7–10]. While many of these experiences may not be categorized as genuine delusions or hallucinations by clinicians [7] and hence, may be more aptly called “psychotic-like” experiences, they have a risk factor profile that is similar to psychotic disorders [9, 10], have a similar structure [8], are disabling [11] and, in many cases, predict future clinical psychosis [12, 13]. The present study aimed to further extend research on the clinical significance of the common psychotic-like experiences by examining their association with interpersonal violence in a population sample.

Methods

Sample

Sample for the study was drawn from the 2001 US National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA). The design of the NHSDA is described in detail elsewhere [14]. Briefly, NHSDA is an annual survey of civilians in the 50 States and the District of Columbia. The target population is comprised of residents of households, non-institutional group quarters, and civilians living on military bases who are 12-years old or older. Interviews are conducted in person, using computer-assisted interviewing methods (response rate = 67.3%). The 2001 NHSDA dataset contains a sample of 55,561 individual participants. When weighted by the sampling weights, this sample is representative of the non-institutionalized US population. The sample for this study was limited to 38,132 participants who were 18-years old or older as the psychotic-like experience questions were only asked from participants in this age range.

Assessments

Psychotic-like experiences were ascertained by seven questions asking about unusual experiences in the past 12 months (Appendix A). A summary index was computed by adding the responses to the seven items (range of scores = 0–7, KR-20 = 0.74).

Interpersonal violence was assessed by asking the participants how many times in the past 12 months they had attacked someone “with the intent to seriously hurt” that person (0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10+ times) and whether or not they had been arrested and booked for aggravated assault and for other assault. Participants who lived with a spouse or partner were also asked how many times they had hit or threatened to hit their spouse or partner in the past 12 months (0, 1–2, a few times, many times).

Non-specific psychological distress was ascertained using the K6 screening instrument [15]. The six items on K6 ask how often the participant has felt nervous, restless, hopeless, worthless, extremely sad or that “everything was an effort” during a month’s period in the past 12 months when the participant was “the most depressed, anxious or emotionally stressed.” K6 does not include any psychotic-like experiences. Each item is rated on a scale ranging from “none of the time” (= 0) to “all of the time” (= 4). Thus, K6 scores can range from 0 to 24 (α = 0.91). Construction of K6 and its psychometric properties have been described in more detail elsewhere [15–17].

Impairment in role functioning was ascertained by a 16-item version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale (WHO-DAS) [18] that assessed difficulties in cognitive, social and occupational functioning during a 1-month period in the past 12 months when the participant’s mental health problems interfered most with daily activities. Each item on WHO-DAS is rated on a scale from “no difficulty” (= 0) to “severe difficulty” (= 3). Thus, WHO-DAS scores can range from 0 to 48 (α = 0.92).

Mental health treatment was ascertained by asking if the participant had seen a doctor or mental health professional in the past 12 months for problems with “emotions, nerves, or mental health,” was hospitalized overnight for these problems, was prescribed any medications for these problems, and, if so, for how long.

Substance abuse or dependence were ascertained by a series of questions designed to assess dependence or abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs based on criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) [19]. The illicit drugs included marijuana, hallucinogens, inhalants, cocaine, heroin, and non-medical use of tranquilizers, pain relievers, stimulants, and sedatives.

Aggression in the household was ascertained by three questions, which asked whether the household members often “insult or yell at each other,” have “serious arguments” or “argue about the same things over and over.” Participants were asked to indicate how strongly they agreed with each statement on a scale ranging from “strongly agree” (= 3) to “strongly disagree” (= 0). A summary score was computed by adding scores on these items (score range 0–9, α = 0.85). These questions were only asked from participants who indicated that they lived with someone.

Illegal behaviors other than assault were ascertained by a series of questions about arrests in the past 12 months for the following illegal behaviors: possession, manufacture, or sale of drugs, possession of stolen goods, vandalism, robbery, motor vehicle theft, larceny or other property theft, burglary or breaking and entering, forcible rape, arson and prostitution.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted in four stages. First, the association of psychotic-like experiences with interpersonal violence was assessed using bivariate binary logistic regression models in which the presence of any psychotic-like experience was the predictor variable and violent behavior the outcome of interest. To examine dose–response trends in the association of psychotic-like experiences and violence, the above analyses were repeated with the number of psychotic-like experiences (0, 1, 2, 3+) as a predictor variable. Participants with three or more psychotic-like experiences were combined for these analyses to avoid unstable estimates due to small sample size.

Second, the association of psychotic-like experiences with the more common forms of interpersonal violence recorded in NHSDA 2001 were examined using multivariate binary logistic regression models. The full range of the variable of number of psychotic-like experiences (0–7) was entered into these models as a continuous variable. Analyses controlled for potentially confounding variables found to be significantly (P < 0.05) associated both with psychotic-like experiences and with violent behaviors. Potentially confounding variables were identified using separate bivariate binary logistic regression models for psychotic-like experiences and for the target violent behaviors.

Third, to assess whether the increased risk of violence is limited to a specific constellation of experiences such as those involving experiences of “threat” (e.g., paranoid ideations) and “control over-ride” (e.g., influence ideations) [4, 5] or is a common attribute of all psychotic-like experiences, the association of these experiences with violent behaviors were examined using bivariate and multivariate binary logistic models. Bivariate analyses compared participants who reported one psychotic-like experience only with those who reported none. Multivariate analyses included the full sample and assessed the contribution of each experience to the likelihood of interpersonal violence by entering all experiences simultaneously into the model.

The analyses for association of psychotic-like experiences with violence described above examined the strength of the association. The potential contribution of psychotic-like experiences to the overall burden of violence in the community would depend both on the strength of the association and the base rate of psychotic-like experiences in the community. To directly assess the potential contribution of psychotic-like experiences to the community burden of violence, prevalence of these experiences among all participants who reported interpersonal violence were assessed. All analyses adjusted for the complex design of the NHSDA survey by taking into account the sampling weights, clustering and stratification of the data. The svytab and svylogit subroutines of Stata 7.0 [20] were used for these analyses. All percentages reported were weighted.

Results

Prevalence of self-reported psychotic-like experiences and characteristics of individuals who report such experiences

Psychotic-like experiences were reported by 5.1% (N = 2,584) of adults in the community. The most common contents were hearing voices (2.2%, N = 1,139), seeing visions (2.0%, N = 532), reference ideations (1.4%, N = 419), influence experiences (1.0%, N = 295), paranoid ideations (1.0%, N = 277), thoughts stolen (0.8%, N = 218) and thoughts inserted (0.5%, N = 160). These experiences were significantly correlated with each other (range of Pearson correlation coefficients = 0.23–0.44, median = 0.32).

Compared to participants without psychotic-like experiences, those with these experiences were more likely to be in the younger age group, to be from the non-Hispanic black ethnicity, to have fewer years of education, to be unemployed, to have a lower family income and to live alone. They were also more likely to report psychological distress and impairment in role functioning, to have substance abuse or dependence and to report being arrested for illegal behaviors other than assault. About 30.0% of the individuals with psychotic-like experiences compared to 10.0% of those without such experiences had received mental health care in the past year. Participants with psychotic-like experiences were also more likely to report a high level of verbal aggression in their households.

Prevalence of interpersonal violence

The most common types of self-reported violent behavior in this community sample were intimate partner violence, reported by 1.8% (N = 834) of all participants and 2.9% of participants living with a spouse or partner, and attacking someone with the intent of hurting that person, reported by 1.5% (N = 1,086) of the participants. Arrests due to assault was relatively less common. Arrest for aggravated assault was reported by 0.2% (N = 122) of the participants and arrest for other assault by 0.3% (N = 221).

Association of psychotic-like experiences and violence

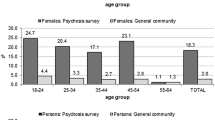

Presence of any psychotic-like experience was associated with increased prevalence of interpersonal violence, including attacking someone with the intent of hurting that person (Odds Ratio [OR] = 5.72, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 4.44–7.38, t = 13.47, P < 0.001), intimate partner violence (OR = 4.97, 95% CI = 3.68–6.71, t = 10.48, P < 0.001), arrests for aggravated assault (OR = 5.12, 95% CI = 2.76–9.53, t = 5.17, P < 0.001), and arrests for other assault (OR = 3.65, 95% CI = 2.18–6.11, t = 4.93, P < 0.001). Furthermore there was a dose–response association between the number of psychotic-like experiences and violent behaviors: the greater the number of experiences, the greater the odds ratio of violence (Figure 1).

Odds ratios (±95% CI) associated with number of psychotic-like experiences obtained from logistic regression models predicting violent behavior. Personal Attack stands for self-reported attacks on a person with the intent to seriously hurt that person. Intimate partner violence stands for self-report of hitting or threatening to hit partner. Aggravated assaults and other assaults stand for the self-reports of arrests for aggravated assaults or other assaults.

To avoid unstable estimates, multivariate analyses were limited to the two more common forms of violent behaviors: attacking someone with the intent of hurting that person and intimate partner violence. These analyses adjusted for potentially confounding variables associated with both psychotic-like symptoms and violent behaviors. Number of psychotic-like experiences remained associated with both behaviors at a statistically significant level after adjusting for these variables (Table 1). The magnitude of effect for psychotic-like experiences in the multivariate models was consistent across the two forms of violent behaviors. Odds ratios of 1.20 (Table 1) indicate that each additional experience increased the risk of the target behavior by about 20%.

In addition, the pattern of association of different risk factors with the two forms of interpersonal violence varied. Attacking someone with the intent of hurting that person appeared to be selectively associated with male gender, lower education, higher non-specific psychological distress and arrests for illegal behavior other than assault, whereas, hitting or threatening to hit spouse or partner was selectively associated with impairment in role functioning. Furthermore, while level of household aggression was associated with both forms of self-reported violence, its association was much stronger with intimate partner violence, as indicated by the relative magnitude of the odds ratios (Table 1).

Is risk of violence associated with specific types of psychotic-like experiences?

In analyses comparing participants with one psychotic-like experience only, versus none, almost all such experiences were associated with increased risk of violent behavior, as indicated by odds ratios larger than 1 (Table 2); although not all odds ratios were greater than 1 at a statistically significant level. In the multivariate models in which all experiences were entered simultaneously, fewer experiences were independently associated with violent behaviors. There was considerable variation across experiences in the two sets of analyses, and there was no indication that the increased risk was limited to experiences with a content of “threat” (paranoid ideations) or “control over-ride” (influence experiences, thoughts inserted, thoughts stolen). Nevertheless, the association of perceptual experiences, specially seeing visions, and paranoid ideations with violence appeared to be more consistent than other experiences.

Prevalence of psychotic-like experiences among adults who report interpersonal violence

Psychotic-like experiences were reported by 22.5% of participants who reported attacking someone with the intent of seriously hurting that person, 21.6% of those who reported arrests for aggravated assault, 16.4% of those who reported arrests for other assaults and 14.8% of those who reported threatening or hitting their spouses or partners. Furthermore, among participants who reported any incidents of attacking someone with the intent of hurting that person, those with psychotic-like experiences were twice more likely than participants without these experiences to report more than one incident (26.6% vs. 13.9%, respectively; design-based F test = 9.28, df = 1, 900, P = 0.002). Similarly, among participants who reported any incidents of hitting or threatening to hit spouse or partner, those with psychotic-like experiences were almost twice more likely than participants without these experiences to report multiple incidents of such behavior (42.7% vs. 25.5%, respectively; design-based F test = 7.83, df = 1,900, P = 0.005).

Discussion

The findings of this study are constrained by several limitations. First, this study focused on self-reported psychotic-like experiences. The clinical significance of these experiences was not ascertained by a clinician. Furthermore, NHSDA 2001 did not assess psychiatric diagnoses. However, based on findings from past research [9, 21], it is quite likely that only a minority of these experiences would be identified as clinically significant symptoms and only a small proportion of the individuals with these experiences would be identified as cases of psychotic disorders by a clinician. Although self-reported psychotic-like experiences are associated with considerable distress and impairment in role functioning and adverse social outcomes, their association with violent behaviors may be different than that for clinician-diagnosed psychotic symptoms. In the McArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, only self-reported “threat/control override” symptoms were associated with higher rates of violence in one follow-up evaluation; clinician-diagnosed symptoms showed no such relationship [22, 23]. Second, ascertainment of interpersonal violence was also based on self-report and not on administrative records or informant reports. However, there is evidence that self-reports of violent behaviors correspond reasonably well with administrative records [24] and are predictive of future offences [25]. Also, there is some evidence that the use of computer-assisted interviewing method increases reporting of interpersonal violence and other socially undesirable behaviors [26]. Administrative sources of data on violence capture only a small proportion of violent acts that lead to arrests or formal reporting. The majority of incidents, especially in a domestic context, remain undetected. Even informants, unless they accompany subjects all the time, would not be able to provide information on all incidents. As a result, the yield of these sources of information is generally lower than self-report. In the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, for example, more than 81% of all incidents of interpersonal violence were ascertained by self-reports; only less than 19% were ascertained exclusively from agency records or collateral informants [2]. Third, the present study was based on cross-sectional data. A causal relationship cannot be inferred from such data. While an attempt was made to control for the potential confounders of the relationship of psychotic-like experiences and violent behavior, only a limited number of potential confounder variables are included in the NHSDA data. The results of this study, therefore, need to be corroborated in future longitudinal studies. Fourth, this study only examined community dwelling adults. Many individuals who are prone to violent behavior reside in correctional facilities where the rates of psychopathology are also much higher than in household samples [27]. Therefore, studies in household samples likely underestimate the overall association of psychopathology and violence. Finally, the prevalence of psychotic-like symptoms in different community surveys vary widely. For example, the Epidemiological Catchment Area study [28], which used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), reported that only 3.3% of the general US population sample endorsed any of the A criteria of DSM-III schizophrenia (which includes delusions, third person auditory hallucinations, auditory hallucinations of voices conversing and loosening of associations). Rates of self-reported psychotic symptoms in community studies that used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) have been higher [9, 21]. For example, 17.5% of adults in a community study in Netherlands reported at least one of the 17 CIDI symptoms [9]. Such variations in rates of symptoms and syndromes across surveys are common [29] and are likely due to variations in instruments, wording of questions and the age distributions of samples.

Despite these limitations, the data presented here provide some insights into the relationship of psychopathology and interpersonal violence in the community. Self-reported psychotic-like experiences appear to be associated with violent behaviors in non-clinical samples drawn from the general population. Even after adjusting for various socio-demographic and clinical variables in multivariate models, each additional psychotic-like symptom increased the likelihood of violence by about 20% (adjusted odds ratios of 1.20). This is likely a conservative estimate as some of the clinical variables adjusted for in the models might be consequences of psychotic-like symptoms rather than confounding factors (e.g., impairment in role functioning). It is also notable that the association of psychotic-like experiences with violence persisted after controlling for the effects of such potential confounders as comorbid alcohol and drug abuse or dependence and level of aggression in the household.

These findings extend the relationship of psychopathology and violence far beyond the confines of formal categories of mental disorders such as schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders to experiences in the general population. It appears that as the psychotic experiences have a distribution in the general population, so does the associated risk of violence. This view is also consistent with findings from the few other studies that examined the association between psychotic-like experiences and violent behavior in general population samples [4, 5].

While past research has repeatedly shown an association between psychotic symptoms and violence, little is known about the mechanisms involved. Cognitive theories, such as “threat/control override” hypothesis, explain violent behavior as a response to the threatening content of symptoms [4, 5, 30]. The present study, however, did not find a strong evidence that the association with violence is limited to experiences with a “threat/control override” content. Almost all psychotic-like experiences appear to somewhat increase the risk of violence when assessed individually, although the association appears to be more consistent for unusual perceptual experiences and paranoid ideations than for experiences of influence or of thoughts being inserted or stolen.

Another potential explanation for the association of psychotic-like experiences and violence is increased stress reactivity among individuals with psychotic and psychotic-like symptoms [31]. Individuals with these symptoms may experience common negative interpersonal interactions as more stressful and react accordingly. A study of patients with psychotic disorders and their first-degree relatives found that both groups experienced increased levels of stress reactivity compared to a general population control group [31]. The possible mediating role of stress reactivity in the relationship of psychotic-like symptoms and interpersonal violence needs to be examined in future research.

Finally, it is possible that a third factor explains the association of psychotic-like symptoms and interpersonal violence. For example, there is some evidence that child abuse is related to both psychotic-like symptoms [32] and violent behavior [33] in adulthood.

Not only the mechanisms linking psychotic-like symptoms to interpersonal violence remain unclear, but also the potential impact of various interventions on the violence associated with these symptoms requires clarification. In the present study, receiving mental health care was not associated with lower risk of violent behavior among participants with psychotic-like symptoms. This finding is inconsistent with the results of a naturalistic study, which reported reduction in violence among psychiatric patients who received outpatient mental health treatment [34].

Without a better understanding of the nature and the clinical relevance of psychotic-like symptoms, it may not be wise to draw policy implications from these data. Nevertheless, the data do imply that psychotic-like symptoms contribute meaningfully to the community burden of violence. One out of every five individuals who report having attacked someone in the past year with the intent of seriously hurting that person or who report having been arrested for aggravated assault, also report psychotic-like experiences, as do one out of six who report being arrested for any assault and one out of seven who report intimate partner violence. Furthermore, individuals with psychotic-like experiences are more likely to repeatedly commit acts of violence and the risk of violent acts proportionally increases with the number of psychotic-like experiences. In view of the adverse clinical and social outcomes associated with self-reported psychotic-like experiences, further examination of these common but elusive experiences seems justified.

References

Angermeyer MC, Cooper B, Link BG (1998) Mental disorder and violence: results of epidemiological studies in the era of de-institutionalization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33(Suppl 1):S1–S6

Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Roth LH, Silver E (1998) Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:393–401

Torrey EF (1994) Violent behavior by individuals with serious mental illness. Hosp Community Psychiatry 45:653–662

Link BG, Stueve A, Phelan J (1998) Psychotic symptoms and violent behaviors: probing the components of “threat/control-override” symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33(Suppl 1):S55–S60

Swanson J, Borum R, Swartz MS, Monahan J (1996) Psychotic symptoms and disorders and the risk of violent behaviour in the community. Crim Behav Ment Health 6:309–329

Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Roth LH (1999) Dimensional approach to delusions: comparison across types and diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry 156:1938–1943

Bak M, Delespaul P, Hanssen M, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W, van Os J (2003) How false are “false” positive psychotic symptoms? Schizophr Res 62:187–189

Stefanis NC, Hanssen M, Smirnis NK, Avramopoulos DA, Evdokimidis IK, Stefanis CN, Verdoux H, Van Os J (2002) Evidence that three dimensions of psychosis have a distribution in the general population. Psychol Med 32:347–358

van Os J, Hanssen M, Bijl RV, Vollebergh W (2001) Prevalence of psychotic disorder and community level of psychotic symptoms: an urban–rural comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:663–668

van Os J, Hanssen M, Bijl RV, Ravelli A (2000) Strauss (1969) revisited: a psychosis continuum in the general population? Schizophr Res 45:11–20

Olfson M, Lewis-Fernandez R, Weissman MM, Feder A, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky D, Fuentes M (2002) Psychotic symptoms in an urban general medicine practice. Am J Psychiatry 159:1412–1419

Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Kwapil TR, Eckblad M, Zinser MC (1994) Putatively psychosis-prone subjects 10 years later. J Abnorm Psychol 103:171–183

Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H (2000) Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: a 15-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:1053–1058

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2002) Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume II. Technical Appendices and Selected Data Tables. (Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-18, DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3759). SAMHSA, Rockville, MD

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SL, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:184–189

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32: 959–976

Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G (2003) The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol Med 33:357–362

Rehm J, Ustun TB, Shekhar S, Nelson CB, Chatterji S, Ivis F, Adlaf E (1999) On the development and psychometric testing of the WHO screening instrument to assess disablement in the general population. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 8:110–123

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn (DSM-IV). APA, Washington, DC

StataCorp (2001) Stata Statistical Software, Release 7.0. Stata Corporation, College Station, TX

Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC (1996) Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample. The National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53:1022–1031

Monahan J, MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (2001) Rethinking risk assessment: the MacArthur study of mental disorder and violence. Oxford University Press, New York

Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J (2000) Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur violence risk assessment study. Am J Psychiatry 157:566–572

Crisanti A, Laygo R, Junginger J (2003) A review of the validity of self-reported arrests among persons with mental illness. Curr Opin Psychiatry 16:565–569

Mills JF, Loza W, Kroner DG (2003) Predictive validity despite social desirability: evidence for the robustness of self-report among offenders. Crim Behav Ment Health 13:140–150

Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL (1998) Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science 280:867–873

Human Rights Watch (2003) Ill-Equipped: U.S. Prisons and Offenders with Mental Illness. Human Rights Watch, New York

Robins LN, Regier DA (1991) Psychiatric disorders in American: the epidemiologic catchment area study. Free Press, New York

Regier DA, Kaelber CT, Rae DS, Farmer ME, Knauper B, Kessler RC, Norquist GS (1998) Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments for mental disorders. Implications for research and policy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:109–115

Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, Tuckwell V (1997) Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 26:181–190

Myin-Germeys I, van Os J, Schwartz JE, Stone AA, Delespaul PA (2001) Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:1137–1144

Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen M, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, van Os J (2004) Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109:38–45

Heyman RE, Slep AM (2002) Do child abuse and interparental violence lead to adulthood family violence? J Marriage Family 64:864–870

Skeem JL, Monahan J, Mulvey EP (2002) Psychopathy, treatment involvement, and subsequent violence among civil psychiatric patients. Law Hum Behav 26:577–603

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Psychotic-like experiences assessed in the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse.

The next questions are about unusual experiences that some people have. When you answer these questions, please do not include times when you were dreaming or half asleep, had a high fever, or were under the influence of llegal drugs or alcohol. |

During the past 12 months, have you heard voices—that is, voices that other people said did not exist, voices coming from inside your head, or voices coming out of the air when there was no one around?* (hearing voices) |

During the past 12 months, have you seen a vision—that is, something that other people could not see?* (seeing visions) |

During the past 12 months, have you felt that a force was taking over your mind and trying to make you do things you didn’t want to do?* (influence experiences) |

During the past 12 months, have you felt that some force was inserting thoughts directly into your head by means of X-rays or laser beams or other methods?* (thoughts inserted) |

During the past 12 months, have you felt that your own thoughts were being stolen out of your mind by someone or something you did not have control over?* (thoughts stolen) |

During the past 12 months, have you felt that some force was trying to communicate directly with you by sending special signs or signals that only you could understand?* (reference ideations) |

During the past 12 months, have you believed that there was an unfair plot going on to harm you or to have people follow you—when your family and friends did not believe that this was happening?* (paranoid ideations) |

*Each question was followed by the statement: “Remember, please do not include times when you were dreaming or half asleep, had a high fever, or were under the influence of illegal drugs or alcohol.” |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mojtabai, R. Psychotic-like experiences and interpersonal violence in the general population. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 41, 183–190 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0020-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0020-4