Abstract

Background

Patients' satisfaction with care may be an important factor in relation to adherence to treatment and continued psychiatric care. Few studies have focused on satisfaction in patients with depressive and bipolar disorders.

Method

A comprehensive multidimensional questionnaire scale, the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale-Affective, was mailed to a large population of patients with depressive or bipolar disorders representative of outpatients treated at their first contact to hospital settings in Denmark.

Results

Among the 1,005 recipients, 49.9% responded to the letter. Overall, patients were satisfied with the help provided, but satisfaction with the professionals' contact to relatives was low. Younger patients (age below 40 years) were consistently more dissatisfied with care especially with the efficacy of treatment, professionals' skills and behaviour and the information given. There was no difference in satisfaction between genders or between patients with depressive disorder and patients with bipolar disorder.

Conclusion

There is a need to strengthen outpatient treatment for patients discharged from a psychiatric hospital diagnosed of having affective disorders, focusing more on information and psychoeducation for patients and relatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been increasingly clear that non-adherence to treatment is a major reason for relapse and recurrence in depressive and bipolar disorders ranging from 10 to 60% (median 40%) [1–3]. Patient satisfaction may be an important factor in relation to adherence to treatment and continued psychiatric care [4, 5]. Several studies have investigated patient satisfaction with specific psychiatric services such as inpatient psychiatric care [6–8] and community-based psychiatric services [9, 10], and a bulk of studies have focused on satisfaction among patients with schizophrenia [9, 11–13]. Surprisingly, few studies have specifically investigated satisfaction in patients with depressive and bipolar disorders [14–18]. Although satisfaction has been demonstrated to be a multidimensional concept [4], instruments have often been limited to a few broad items which only require one or two dimensions of mental health care [19]. During recent years, a well-validated comprehensive multidimensional scale, the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale (VSSS), has been developed for measuring satisfaction among patients with schizophrenia or other psychosis [19, 20]. The VSSS has been translated and cross-culturally adapted to a number of languages, among others English, Dutch, Spanish and Danish, by using focus groups [21]. There exist no comprehensive multidimensional scale developed for patients with affective disorders, and accordingly, the few studies on satisfaction in patients with depressive and bipolar disorders have used less comprehensive scales with items between one and ten only [14–18]. We transformed the VSSS into a questionnaire to be used for patients with affective disorders, the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale-Affective (VSSS-A). Among the 54 items in the VSSS, 19 items were found to have more relevance for patients with schizophrenia than for patients with affective disorder and were omitted (e.g. regarding living in sheltered accommodation, help in obtaining welfare benefits or exemptions, etc.; see “Materials and methods”). Minor adjustments were made on the wording of the remaining 35 items, but no changes in the meaning or in the corresponding scoring system were made.

The aim of the present study is to characterise satisfaction with service as identified with the VSSS-A among patients treated at their first contacts with hospital settings for depressive and bipolar disorders and to relate these findings to socio-demographic and clinical variables. We wanted to investigate satisfaction as measured using the VSSS-A in relation to age and gender and to test whether the VSSS-A is different between patients with depressive disorder and patients with bipolar disorder and whether the score is related to the number of severe affective episodes patients had experienced.

Patients were identified using the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (DPCRR) [22] as having depressive disorder or bipolar disorder at the first ever discharge or at the third discharge from a psychiatric hospital or ward in Denmark. Additionally, patients treated as outpatients at psychiatric ambulatories or community psychiatric centres for bipolar disorder were included.

Materials and methods

The register

The DPCRR is nationwide with registration of all psychiatric hospitalisations of 5.3 million inhabitants of Denmark [22]. Since January 1, 1995 the register included information on patients in psychiatric ambulatories and community psychiatric centres.

All the inhabitants of Denmark have a unique personal identification number [Civil Person Registration number (CPR-number)] that can be logically checked for errors; hence, it can be established with great certainty if a patient has had contact with psychiatric service previously, irrespective of changes in name etc. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [23], has been used in Denmark since January 1, 1994.

The sample

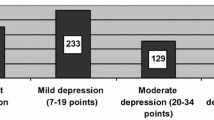

A total of 1,005 patients who were alive and had a home address in Denmark at the time of the investigation were identified from the DPCRR as follows:

-

1.

A random sample of 25% of patients diagnosed as having single or recurrent depression (ICD-10, DF32–33) at the first ever discharge from a psychiatric hospital during year 2002 (N=311).

-

2.

All patients diagnosed as having recurrent depression (ICD-10, DF33) at the third discharge from a psychiatric hospital during year 2002 (N=213).

-

3.

All patients diagnosed as having mania/bipolar affective disorder (ICD-10, DF30–31) at the first ever discharge from a psychiatric hospital during year 2002 (N=181).

-

4.

All patients diagnosed as having bipolar affective disorder (ICD-10, DF31) at the third discharge from a psychiatric hospital during year 2002 (N=195).

-

5.

All patients who at their first ever outpatient contact at a psychiatric ambulatory or community psychiatric centre got a diagnosis of mania/bipolar affective disorder (ICD-10, DF30–31) during year 2001 or 2002 (N=105).

Patients were included in this way to get a greater variation in the number of admissions.

Outpatient care service following discharge from psychiatric hospitals or wards

In Denmark, patients who are discharged from psychiatric hospitals or wards in Denmark with a diagnosis of depressive or bipolar disorder are followed as outpatients by a psychiatric ambulatory or community psychiatric centre, by a private practising specialist in psychiatry or by their general practitioner. Patients with bipolar disorder are more often offered care by psychiatric ambulatories or community psychiatric centres and patients with depressive disorder are more often offered service by their general practitioner.

The Verona Service Satisfaction Scale-Affective

Among the 54 items in the VSSS, 19 items were found to have more relevance for patients with schizophrenia than for patients with affective disorder (items 2, 4, 10, 22, 25, 28, 35, 37, 42, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 and 54, as numbered in the paper by Ruggeri et al. [13]; e.g. regarding professional competence of the nursing staff and social workers as such persons are not employed in psychiatric or general practise, living in sheltered accommodation which is seldom for patients with affective disorders, help in obtaining welfare benefits or exemptions, etc.) and were omitted. Minor adjustments were made on the wording of the remaining 35 items, but no changes in the meaning or in the corresponding scoring system were made.

The VSSS-A is scored the same way as the VSSS [13]. For items 1–32, satisfaction ratings are on a five-point Likert scale (1=terrible, 2=mostly dissatisfactory, 3=mixed, 4=mostly satisfactory, 5=excellent). Items 33–35 consist of three questions regarding medication prescription, individual psychotherapy and group psychotherapy as in the VSSS (items 41, 43, 48). The 35 items of the VSSS-A are subdivided into seven dimensions the same way as in the VSSS [13]: overall satisfaction, professionals' skills and behaviour, information, access, efficacy, types of intervention, relative's involvement (for details, see subtext in Table 2).

Besides the VSSS-A, patients also scored satisfaction on the WHO Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (WHO-TSQ; [24]). Self-rating of psychopathology was assessed using the Symptom Rating Scale for Depression and Anxiety (BDI-42; [25]), including assessment of depressive symptoms by the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; [26]) and manic symptoms by the six-item Mania Subscale [25].

The questionnaires were mailed to the patients as part of a larger survey during spring 2004. The local ethical committee approved the study (KF 01-159/02), allowing mailing of one reminder only if patients did not respond to the initial letter.

Statistical analysis

In univariate analyses, categorical data were analysed using chi-square test (two-sided), and continuous data were analysed using the Mann–Whitney test for two independent groups. In multiple regression analyses, the seven dimensions of the VSSS-A were included as outcome, and gender, age at first contact, number of admissions and type of disorder (depressive vs bipolar disorder) were included as predictive variables.

P<0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. SPSS software package for windows, version 11.0, was used [27].

Results

A total of 1,005 patients were identified in the register with a diagnosis of depressive disorder (N=524) or mania/bipolar disorder (N=481) and as being alive and living in Denmark at the time of the study. A letter with questionnaires including the VSSS-A was mailed to these 1,005 patients. In total, 16 letters were returned: 7 due to unknown address, 6 as the patients did not understand Danish, 2 as the patients according to relatives were demented and 1 as the patient has died. Among the remaining 989 patients who were potentially able to respond to the questionnaires, 493 patients accomplished the questionnaires (258 patients with depressive disorder and 235 with bipolar disorder), this corresponds to a response rate of 49.9%. There was no difference in the response rate between patients with depressive disorder (50.0%) and patients with bipolar disorder (49.7%, P=1.0). As can be seen in Table 1, among patients with depressive disorder, significantly more women (55.3%), than men (42.0%), responded to the questionnaires (P=0.004), but there were no gender difference among patients with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in age at first treatment contact or in the number of admissions between responders and non-responders for either of the disorders.

The responses to the 32 items of the VSSS-A are presented in Table 2 as the mean (SD) values for each item for patients with depressive disorder and patients with bipolar disorder (also for comparison with future studies). The higher the score, the more satisfied the patient was. There were statistical differences in the scores between depressive and bipolar disorders on five items (items 7, 16, 19, 26, and 27). Furthermore, the percent proportions of patients who scored 4 or 5 (mostly satisfactory or excellent) are given for the total sample. In general, patients were satisfied with the help received, scoring above 50%. However, for nine items (indicated in bold), the scores were below 50%. Among these nine items, seven concerned contact with relatives. In fact, all items concerning relatives were scored with a degree of satisfaction below 50%. Furthermore, one item concerned help in relation to work (item 30), and one item concerned help in relation to unwanted effects of medication (item 31).

In univariate analyses, patients older than 40 years were significantly more satisfied than younger patients as indicated by the total VSSS-A score and on all dimensions except “access” (Table 3). There was a significant direct correlation between age and satisfaction as indicated by the total score on the VSSS-A (p=0.0001, r=0.19).

Furthermore, Table 4 presents results from multiple regression analyses with the total score of the VSSS-A and with the seven dimensions as outcomes, and with simultaneous inclusion of gender, age at first contact, number of admissions and type of disorder (depressive vs bipolar disorder) as predictive variables. As can be seen, older age at first contact was associated with higher satisfaction on all measures, however, only significantly in the total VSSS-A score and in four of the seven dimensions. There were no significant differences according to gender, number of admissions or type of disorder in any measure of satisfaction. The above mentioned multiple regression models were repeated, including further the variable describing the type of current physician during outpatient treatment (specialist in psychiatry in a psychiatric ambulatory, physician or specialist in psychiatry in a community psychiatric centre, specialist in psychiatry in private practise, general practitioner). There were no significant associations between any of the scores and the type of physician (p>0.05).

There was a low to moderate negative correlation between the prevalence of self-rated depressive symptoms as indicated by scores on the BDI-21 score and total score on the VSSS-A (P=0.0001, r=−0.35). In contrast, there was a low to moderate positive correlation between manic symptoms as indicated by scores on the six-item Mania Subscale and the VSSS-A. Although age at first contact did not correlate with BDI-21 (P=0.2, r=−0.06) or the six-item Mania Subscale (P=0.2, r=0.06), inclusion of these variables in the above mentioned multiple regression model with total score on the VSSS-A as the outcome resulted in a slightly reduced and borderline significant effect of age [B=0.009, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.001 to 0.019, P=0.07].

There was a high correlation between the total score on the VSSS-A and the total score on the WHO-TSQ (Pearson correlation r=0.62, P<0.0001).

Discussion

Overall, outpatients with depressive or bipolar disorders who had been discharged from their first hospital admissions were satisfied with the help provided, i.e. the professionals' skills and behaviour, the information, the access of the service, the efficacy and the type of intervention provided. In contrast, satisfaction with the professionals' contact with relatives was low, with the majority scoring the items as terrible, mostly dissatisfactory or mixed. Older patients (age above 40 years) were consistently more satisfied with treatment with no differences among genders. There was no difference in satisfaction between patients with depressive disorder and patients with bipolar disorder, and there was no statistical significant effect of the number of psychiatric hospitalisations or the type of the current physician (specialist in psychiatry in a psychiatric ambulatory, physician or specialist in psychiatry in a community psychiatric centre, specialist in psychiatry in private practise, general practitioner). The study included a large population of patients with depressive or bipolar disorders that is representative of patients treated in hospital settings in Denmark. Furthermore, a comprehensive multidimensional questionnaire regarding satisfaction with care was used, which no other study on satisfaction with care in patients with affective disorders has used.

During recent years, a number of studies have revealed that it is important that relatives encompass patients with bipolar disorder. A high burden level on relatives of patients with bipolar disorder [28] and certain family attitudes such as high expressed emotion [29–33] and negative affective style [34] may worsen the course of bipolar disorder. Although scarcely investigated, psychoeducational intervention on caregivers and relatives of patients with bipolar illness has been found to reduce the subjective burden of the relatives [35]. Our study reveals that patients discharged with diagnoses of bipolar disorder as well as depressive disorder are dissatisfied with the professionals' contact with relatives in the current service. This finding is in accordance with findings among patients with schizophrenia [13]. In Denmark, there has been little professional attention on relatives of patients with affective disorders, and there seems to be a need to strengthen the contact with the relatives. In addition, more studies are needed to investigate the effect of psychoeducation and other interventions in relation to relatives.

Older patients were consistently found to be more satisfied with care in the present study. This is in accordance with the findings in a meta-analysis on satisfaction with medical care, concluding that among a number of variables, age has the strongest positive correlation with satisfaction with care [36]. The mean correlation between age and satisfaction was r=0.13, a correlation comparable to the correlation between age and total score on the VSSS-A found in the present study (r=0.19). Not only bipolar disorder but also depressive disorder may present with first episodes when patients are 20 or 30 years old; thus, the finding that young patients are dissatisfied with care has to be taken seriously. More specifically, younger patients were more dissatisfied with the efficacy of treatment, professionals' skills and behaviour and the information given (Table 4). These findings emphasize the need for intensifying and strengthening outpatient treatment for patients discharged from a psychiatric hospital with diagnoses of affective disorders. Specialized centres for patients with severe affective disorders may offer a more systematic treatment with focus on information and psychoeducation for patients and relatives.

There was no difference in satisfaction with care between genders in the present study, which is also in accordance with the result from the above mentioned meta-analysis [36].

We found no difference in the degree of satisfaction between patients with depressive disorder and patients with bipolar disorder. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has compared satisfaction with care between depressive and bipolar patients. Furthermore, satisfaction with care did not vary with the number of psychiatric hospitalisations. We are not aware of any other study that has investigated the relationship between course of illness and satisfaction with care. To avoid bias, such a study has to be conducted prospectively as discussed in the following section on caveats of the present study.

Caveats of the study

The VSSS is designed to assess satisfaction with care primarily among patients with schizophrenia who often receive care in community psychiatric centres, including close contact to nurses and social workers [19]. Patients with affective disorders are more often treated in psychiatric or general practise; thus, the VSSS was modified, leaving out items with less relevance for patients with affective disorders, resulting in the VSSS-A. Whilst this may make the VSSS-A questionnaire more acceptable for patients with affective disorders in general, it is possible that some of these items (e.g. living in sheltered accommodation, help in obtaining welfare benefits) may have been relevant to a small group of patients with the most severe type of bipolar disorder.

Approximately 50% of the patients answered the letter, a rate that equals the response rate in satisfaction questionnaire surveys in general [37]. Contrary to most studies on satisfaction conducted by mail, we did not exclude very ill patients, patients who had been involuntary hospitalised, patients with dementia, the illiterate or emigrants, etc. [37]. The questionnaires were mailed to all patients who gained contact to a psychiatric hospital health care as described in the inclusion criteria. Additionally, a number of patients who received the questionnaires may have been in a current acute affective episode, hindering them from responding. Patients who responded to the VSSS-A were rather satisfied with care; hence, we cannot exclude that more dissatisfied patients may have responded in a less degree. However, we do not believe that this has caused major bias in the revealed associations as only slightly more women responded to the questionnaire among patients with depressive disorder and as the response did not vary according to age, type of disorder or number of hospitalisations (Table 1). Although there was no difference in the response rate among patients with a poor vs better course of illness as indicated by many vs few hospitalisations, we cannot exclude that the prevalence of other indicators of a poor outcome, such as co-morbidity with substance abuse or personality disorders, was higher among non-responders.

Satisfaction with care has been found to be associated with the prevalence of depressive symptoms as indicated by self-assessment [14, 38], and it has been recommended to address the effect of depressive symptoms by using methods of statistical control [38]. We found a low to moderate correlation between the prevalence of depressive symptoms and satisfaction with care and adjusting for depressive symptoms in multiple regression analyses, the effect of age became slightly reduced and only borderline significant.

The diagnoses were made by psychiatrist all over Denmark according to ICD-10 and was not standardised for research purposes. ICD-10 does not discriminate between bipolar disorder types 1 and 2 as both are categorised as bipolar disorder [23]. We cannot exclude that some patients may have been misclassified as suffering from depressive disorder instead of bipolar disorder, and that this may have diluted possible differences between the two illnesses.

We do not have information on the number of affective episodes patients have experienced. It is well known that patients are hospitalised for the most severe depressive episodes only (mainly with somatic or psychotic symptoms) and for moderate to severe manic episodes [39]. We cannot exclude that there exist an association between the number of episodes or the duration of the illnesses and satisfaction with care. However, using the number of psychiatric hospitalisations as a measure of the course of illness, we did not find that patients with a more severe course of illness (i.e. more hospitalisations) were less satisfied with care. This finding may be due to bias as those patients who seek hospitalisation many times also may constitute the proportion of patients with severe illness with a more positive view upon treatment and the health care system. Nevertheless, our findings contrast the finding for patients with schizophrenia that lower levels of total service satisfaction, as indicated by the VSSS, has been found to be associated with more hospital admissions [13].

It should be noted that the patients had been hospitalised approximately 2.5 times on average (Table 1), and that patients with many more admissions may present with another degree of satisfaction with care. The study and the analyses of the number of psychiatric hospitalisations were based on cross-sectional data. We plan to conduct a prospective study analysing whether these cross-sectional data on satisfaction with care predict the risk of hospitalisation in the future.

In conclusion, outpatients who have been hospitalised for depressive or bipolar disorders are generally satisfied with the help provided, but there is a low degree of satisfaction with the professionals' contact with relatives. Younger patients are more dissatisfied than older patients, and this may add to deteriorate the prognosis of depressive and bipolar disorders. There is a need to further investigate whether this is actually the case.

References

Lingam R, Scott J (2002) Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 105(3):164–172

Demyttenaere K, Haddad P (2000) Compliance with antidepressant therapy and antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 403:50–56

Hotopf M, Hardy R, Lewis G (1997) Discontinuation rates of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis and investigation of heterogeneity. Br J Psychiatry 170:120–127

Ware JE Jr, Davies-Avery A, Stewart AL (1978) The measurement and meaning of patient satisfaction. Health Med Care Serv Rev 1(1):1–15

Berghofer G, Schmidl F, Rudas S, Steiner E, Schmitz M (2002) Predictors of treatment discontinuity in outpatient mental health care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 37(6):276–282

Kelstrup A, Lund K, Lauritsen B, Bech P (1993) Satisfaction with care reported by psychiatric inpatients. Relationship to diagnosis and medical treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 87(6):374–379

Svensson B, Hansson L (1994) Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care. The influence of personality traits, diagnosis and perceived coercion. Acta Psychiatr Scand 90(5):379–384

Howard PB, Clark JJ, Rayens MK, Hines-Martin V, Weaver P, Littrell R (2001) Consumer satisfaction with services in a regional psychiatric hospital: a collaborative research project in Kentucky. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 15(1):10–23

Eklund M, Hansson L (2001) Determinants of satisfaction with community-based psychiatric services: a cross-sectional study among schizophrenia outpatients. Nord J Psychiatry 55(6):413–418

Rossi A, Amaddeo F, Bisoffi G, Ruggeri M, Thornicroft G, Tansella M (2002) Dropping out of care: inappropriate terminations of contact with community-based psychiatric services. Br J Psychiatry 181:331–338

Malm U, Lewander T (2001) Consumer satisfaction in schizophrenia. A 2-year randomized controlled study of two community-based treatment programs. Nord J Psychiatry 55(Suppl 44):91–96

Knapp M, Chisholm D, Leese M, Amaddeo F, Tansella M, Schene A, Thornicroft G, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Knudsen HC, Becker T (2002) Comparing patterns and costs of schizophrenia care in five European countries: the EPSILON study. European Psychiatric Services: Inputs Linked to Outcome Domains and Needs. Acta Psychiatr Scand 105(1):42–54

Ruggeri M, Lasalvia A, Bisoffi G, Thornicroft G, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Becker T, Knapp M, Knudsen HC, Schene A, Tansella M (2003) Satisfaction with mental health services among people with schizophrenia in five European sites: results from the EPSILON Study. Schizophr Bull 29(2):229–245

Wyshak G, Barsky A (1995) Satisfaction with and effectiveness of medical care in relation to anxiety and depression. Patient and physician ratings compared. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 17(2):108–114

Scholle SH, Peele PB, Kelleher KJ, Frank E, Kupfer D (1999) Satisfaction with managed care among persons with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv 50(6):751

Meredith LS, Orlando M, Humphrey N, Camp P, Sherbourne CD (2001) Are better ratings of the patient–provider relationship associated with higher quality care for depression? Med Care 39(4):349–360

Van Voorhees BW, Cooper LA, Rost KM, Nutting P, Rubenstein LV, Meredith L, Wang NY, Ford DE (2003) Primary care patients with depression are less accepting of treatment than those seen by mental health specialists. J Gen Intern Med 18(12):991–1000

Ludman EJ, Simon GE, Rutter CM, Bauer MS, Unutzer J (2002) A measure for assessing patient perception of provider support for self-management of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 4(4):249–253

Ruggeri M, Lasalvia A, Dall'Agnola R, van Wijngaarden B, Knudsen HC, Leese M, Gaite L, Tansella M (2000) Development, internal consistency and reliability of the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale-European Version. EPSILON Study 7. European Psychiatric Services: Inputs Linked to Outcome Domains and Needs. Br J Psychiatr Suppl 39:s41–s48

Henderson C, Hales H, Ruggeri M (2003) Cross-cultural differences in the conceptualisation of patients' satisfaction with psychiatric services-content validity of the English version of the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38(3):142–148

Knudsen HC, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Welcher B, Gaite L, Becker T, Chisholm D, Ruggeri M, Schene AH, Thornicroft G (2000) Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of outcome measurements for schizophrenia. EPSILON Study 2. European Psychiatric Services: Inputs Linked to Outcome Domains and Needs. Br J Psychiatr Suppl 39:s8–s14

Munk-Jorgensen P, Mortensen PB (1997) The Danish Psychiatric Central Register. Dan Med Bull 44(1):82–84

World Health Organisation (1992) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organisation, Geneva

Bech P, Moses R, Gomis R (2003) The effect of prandial glucose regulation with repaglinide on treatment satisfaction, wellbeing and health status in patients with pharmacotherapy naive Type 2 diabetes: a placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Qual Life Res 12(4):413–425

Bech P (1988) Rating scales for mood disorders: applicability, consistency and construct validity. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 345:45–55

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561–571

SPSS Inc. (2001) SPSS for windows. Release 11.0 (19 Sep 2001) Standard version

Perlick DA, Rosenheck RR, Clarkin JF, Raue P, Sirey J (2001) Impact of family burden and patient symptom status on clinical outcome in bipolar affective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 189(1):31–37

Priebe S, Wildgrube C, Muller-Oerlinghausen B (1989) Lithium prophylaxis and expressed emotion. Br J Psychiatry 154:396–399

Honig A, Hofman A, Rozendaal N, Dingemans P (1997) Psycho-education in bipolar disorder: effect on expressed emotion. Psychiatry Res 72(1):17–22

Mino Y, Shimodera S, Inoue S, Fujita H, Tanaka S, Kanazawa S (2001) Expressed emotion of families and the course of mood disorders: a cohort study in Japan. J Affect Disord 63(1–3):43–49

Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Axelson DA, Kim EY, Birmaher B, Schneck C, Beresford C, Craighead WE, Brent DA (2004) Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 82(Suppl 1):S113–S128

Miklowitz DJ, Wisniewski SR, Miyahara S, Otto MW, Sachs GS (2005) Perceived criticism from family members as a predictor of the one-year course of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 136(2–3):101–111

O'Connell RA, Mayo JA, Flatow L, Cuthbertson B, O'Brien BE (1991) Outcome of bipolar disorder on long-term treatment with lithium. Br J Psychiatry 159:123–129

Reinares M, Vieta E, Colom F, Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Comes M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Sanchez-Moreno J (2004) Impact of a psychoeducational family intervention on caregivers of stabilized bipolar patients. Psychother Psychosom 73(5):312–319

Hall JA, Dornan MC (1990) Patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with medical care: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 30(7):811–818

Gasquet I, Falissard B, Ravaud P (2001) Impact of reminders and method of questionnaire distribution on patient response to mail-back satisfaction survey. J Clin Epidemiol 54(11):1174–1180

Atkinson M, Zibin S, Chuang H (1997) Characterizing quality of life among patients with chronic mental illness: a critical examination of the self-report methodology. Am J Psychiatry 154(1):99–105

Kessing LV (1998) Validity of diagnoses and other register data in patients with affective disorder. Eur Psychiatr 13:392–398

Acknowledgements

The Danish National Board of Health supported the study. Lars Vedel Kessing is employed in a professorship at the University of Copenhagen, funded by The Lundbeck Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kessing, L.V., Hansen, H.V., Ruggeri, M. et al. Satisfaction with treatment among patients with depressive and bipolar disorders. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 41, 148–155 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0012-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0012-4