Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to compare the clinical history and audiovestibular function test results of patients suffering from intralabyrinthine schwannoma or delayed endolymphatic hydrops (DEH).

Patients and methods

Five patients diagnosed with intralabyrinthine schwannoma by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and five patients diagnosed with DEH by locally enhanced inner ear MRI (LEIM) were retrospectively studied.

Results

All patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma or DEH initially presented with hearing loss. Vertigo occurred in two patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma and in all patients with DEH. While audiometry achieved poorer results for patients with intralabyrinthine schwannomas, vestibular function tests revealed normal results in about half of the patients in both groups.

Conclusion

Patients with intralabyrinthine schwannomas may present with clinical symptoms similar to patients suffering from other inner ear disorders such as delayed endolymphatic hydrops and they may obtain similar findings in audiovestibular function tests. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging with locally applied contrast agent may provide evidence of both underlying pathologies.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Ziel der Studie war es, die Krankengeschichte und die Befunde in audiovestibulären Funktionsuntersuchungen bei Patienten mit intralabyrinthärem Schwannom oder „delayed endolymphatic hydrops“ (DEH) zu vergleichen.

Patienten und Methoden

Retrospektiv wurden die Daten von 5 Patienten mit durch MR-Bildgebung diagnostiziertem intralabyrinthärem Schwannom und von 5 Patienten mit durch lokal kontrastverstärkter MR-Bildgebung des Innenohrs (LEIM) bestätigtem DEH analysiert.

Ergebnisse

Alle Patienten mit intralabyrinthärem Schwannom oder DEH stellten sich anfangs mit Hörminderung vor. Schwindel trat bei 2 Patienten mit intralabyrinthärem Schwannom und allen Patienten mit DEH auf. Während die Audiometrie schlechtere Ergebnisse für Patienten mit intralabyrinthärem Schwannom ergab, zeigten vestibuläre Funktionsuntersuchungen Normalbefunde in etwa der Hälfte der Patienten beider Gruppen.

Schlussfolgerung

Patienten mit intralabyrinthärem Schwannom können sich mit ähnlichen Symptomen präsentieren wie Patienten mit anderen Innenohrerkrankungen wie DEH und können ähnliche Befunde in audiovestibulären Funktionsuntersuchungen haben. Hochauflösende MR-Bildgebung mit lokal appliziertem Kontrastmittel kann den Nachweis für beide zugrundeliegenden Pathologien erbringen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Vertigo and hearing loss are common symptoms. The underlying cause can be varied and it poses a diagnostic challenge. A frequent cause of unilateral hearing loss and vertigo are vestibular schwannomas, which in some cases are located within the cochlea and/or the vestibule and are then termed “intralabyrinthine schwannomas.” In this article, we describe the clinical history and audiovestibular findings of five patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma and of five patients with delayed endolymphatic hydrops for comparison.

Background

Vestibular schwannomas (VS) are benign tumors that predominantly arise from the myelin-forming Schwann cells of the vestibulocochlear nerve. The incidence of VS is approximately 1/100,000 per year [1, 15]. VS usually manifest with unilateral hearing loss, tinnitus, balance disorders, or vertigo. VS most commonly arise from the internal auditory canal. More rarely, VS are located within the cochlea and/or – less frequently – the vestibule and are then termed “intralabyrinthine schwannomas” [14, 23]. Patients with intralabyrinthine schwannomas almost always present with slowly progressive hearing loss, which occasionally may deteriorate acutely. They can additionally suffer from vertigo, particularly when the tumor involves the vestibular system [22].

Delayed endolymphatic hydrops (DEH) is characterized by endolymphatic hydrops emerging in patients suffering from longstanding hearing loss [18]. The cause of the hearing loss is varied. The most common causes are juvenile unilateral sensorineural hearing loss of undetermined etiology and viral labyrinthitis. More rarely, the hearing loss is caused by head trauma, acoustic trauma, bacterial labyrinthitis, or meningitis [8, 11, 24]. DEH mostly occurs in the ipsilateral ear and causes recurrent vertigo similar to the symptoms in Menière’s disease. Less frequently, DEH occurs contralaterally and induces fluctuating hearing loss that can be accompanied by tinnitus and episodic vertigo [8]. The pathogenesis of DEH is not fully known. As for ipsilateral DEH, the hypothesis that inner ear damage results in slowly progressive, “delayed” atrophy or fibrous obliteration of inner ear structures with consecutive impaired resorption of the endolymph is widely accepted [17]. With regard to contralateral DEH, the same etiology that initially triggered monaural hearing loss may simultaneously induce a subclinical lesion in the contralateral inner ear, which eventually causes the development of endolymphatic hydrops over the years [8, 19].

Since the diagnosis of DEH is based on the clinical history, it can represent a diagnostic challenge when a patient does not display all typical features of DEH – rotational vertigo attacks with longstanding hearing loss. Furthermore, the symptoms of DEH are similar to those of intralabyrinthine schwannomas. Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops in vivo by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the inner ear has become feasible only recently [13, 26]. Likewise, intralabyrinthine schwannomas can easily be overlooked despite recent progress in MRI technology, since radiographic findings may be very subtle [10, 16]. Both entities are therefore challenging with regard to establishing the diagnosis. In this study, we describe five patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma and compare their clinical history and the results of audiovestibular function tests with those of five patients suffering from imaging-confirmed DEH.

Methods

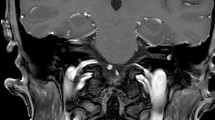

This retrospective study was conducted at a universitary otorhinolaryngology department. All patients diagnosed with intralabyrinthine schwannomas by MRI between 2012 and 2013 were included (n = 5) in the study. An example of an intralabyrinthine schwannoma is shown in Fig. 1. Furthermore, five patients with the diagnosis of delayed endolymphatic hydrops were enrolled in this study for comparison. In the latter group, the presence of endolymphatic hydrops and thus the diagnosis of DEH were proven by locally enhanced inner ear MRI (LEIM), as previously described [6]. An example of an LEIM image showing endolymphatic hydrops is shown in Fig. 2. For all patients, clinical features and audiovestibular function tests as assessed by pure-tone audiometry, caloric irrigation, and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) at the time of diagnosis were evaluated.

a Locally enhanced inner ear magnetic resonance imaging (LEIM) of patient no. 10 with evidence of endolymphatic hydrops in both the cochlear (short arrows) and vestibular (long arrow) compartments. The endolymphatic space is visible as a hypointense (dark) area bulging into the contrast-enhanced (bright) perilymphatic space. b LEIM without evidence of endolymphatic hydrops for comparison. (From [6], used with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.)

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in Table 1.

Intralabyrinthine schwannoma

All patients with the final diagnosis of an intralabyrinthine schwannoma initially presented with hearing loss. Two patients complained of gradually progressive hearing loss, which progressed to deafness within a few years in one patient (no. 4). Two patients complained of sudden sensorineural hearing loss as a singular occurrence, with the hearing loss slowly progressing to deafness in one patient (no. 1) and with deafness being present since the sudden hearing loss in another patient (no. 2). One patient complained of fluctuating hearing loss. Several months to years after the beginning of hearing loss, recurrent vertigo attacks occurred in two patients. In all patients, the diagnosis of an intralabyrinthine schwannoma was established several years after the onset of symptoms. The schwannoma was localized within the cochlea in all five patients. In two patients, it was limited to the cochlea, in two it spread out into the vestibule, and in one it spread out into the internal auditory canal. The diagnostic delay ranged between 2 and 15 years (mean = 9 years). At the time of diagnosis, four patients had already lost serviceable hearing. Caloric irrigation and VEMPs, however, each yielded normal results in two patients.

Delayed endolymphatic hydrops

Likewise, all patients with the final diagnosis of DEH primarily complained of hearing loss. In one patient (no. 6), slowly progressive hearing loss arose from professional noise exposure. In two patients (no. 7 and 9), slowly progressive hearing loss of unknown origin emerged at an early age. In one patient (no. 8), a relatively rapidly progressive hearing loss of unknown origin occurred in middle age. One patient (no. 10) reported sudden sensorineural hearing loss with subsequent widely steady hearing over the years. In the course of several years, recurrent vertigo attacks occurred in all patients. The time period between the onset of hearing loss and the beginning of vertigo attacks ranged between 4 and 27 years, while the time period between the onset of vertigo attacks and the final diagnosis of DEH ranged between 3 months and 5 years. Endolymphatic hydrops was found in the cochlea as well as in the vestibule in all patients. The mean degree of hearing loss at the time of diagnosis amounted to 72 dB. Caloric irrigation and VEMPs were normal in three and two patients, respectively.

Discussion

Symptoms

This case series shows that the history of a patient with intralabyrinthine schwannoma and the one of a patient with DEH may be similar. In this regard, our results are consistent with previous reports that described the symptoms of intralabyrinthine schwannomas to resemble other inner ear disorders such as Menière’s disease [2, 7, 9, 22]. Regardless of the final diagnosis, the initial symptom in all patients of our study cohort was hearing loss. Gradually progressive hearing loss and sudden sensorineural hearing loss as a singular incident without subsequent hearing recovery occurred in both groups, while only one patient with intralabyrinthine schwannoma presented with fluctuating hearing loss, even though a fluctuating form of hearing loss is thought to be rather indicative of endolymphatic hydrops [12]. The pattern of the hearing disorder could therefore not differentiate between intralabyrinthine schwannoma and DEH. The degree of hearing loss, however, differed between groups and was more pronounced in patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma. In four of five patients, hearing loss had progressed to complete deafness.

Vertigo attacks mostly occurred several years after the onset of hearing loss. This was the case in all patients with DEH and in two patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma. However, the percentage of patients suffering from vertigo in these groups cannot be easily compared. In DEH, vertigo is a diagnostic criterion, so that a patient lacking vertigo would not be diagnosed with endolymphatic hydrops [8, 18]. In intralabyrinthine schwannoma, by contrast, vertigo is not a mandatory symptom. In the further course of disease, however, vertigo might occur in patients who have not previously suffered from vertigo.

Diagnostic methods

Audiovestibular function tests did not differentiate between intralabyrinthine schwannoma and DEH. While pure-tone audiometry achieved poorer results for patients with intralabyrinthine schwannomas, vestibular function as assessed by caloric irrigation and VEMPs was normal in about half of the patients in both groups and was affected in the other half. All patients with DEH displayed endolymphatic hydrops both in the cochlea and in the vestibule, with vestibular hydrops overall being more pronounced. There was neither an association between the extent of vestibular hydrops and vestibular function nor between the extent of cochlear hydrops and hearing loss. Previous studies using inner ear MRI to investigate the association between the extent of endolymphatic hydrops and audiovestibular function revealed a significant correlation between the degree of hydrops and hearing loss as well as between the degree of hydrops and disease duration [3, 5, 6, 20, 25]. Intralabyrinthine schwannomas were located in the cochlea in all patients and all patients suffered from deafness or (in one case) from profound hearing loss. The caloric irrigation interestingly yielded normal results in those patients whose schwannoma was limited to the cochlea.

Diagnostic delay

In our study cohort, the diagnostic delay for patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma was up to 15 years. In all patients, several years passed by until the correct diagnosis was set. A confirmation of the diagnosis by histological examination, however, was not performed; the diagnosis was based on the MRI findings. Since radiographic findings in MRI may be very subtle, intralabyrinthine schwannomas can easily be overlooked, so that they are frequently diagnosed only years after the onset of symptoms [10, 16, 21]. Interestingly, patient no. 5 of our study cohort had already undergone MRI twice, 3 and 5 years before the final diagnosis. Both MRI studies had been reported normal, although the presence of a vestibular schwannoma had been taken into consideration with regard to the clinical history. Only on the third MRI was the intralabyrinthine schwannoma reported. Retrospective evaluation of the previous MRI scans, however, revealed that it was present years before and that it could have been detected on both previous MRI studies.

Occurrence

One should therefore bear in mind that an intralabyrinthine schwannoma may be a differential diagnosis of sudden or slowly progressive hearing loss. In fact, intralabyrinthine schwannomas might occur more frequently than indicated in the literature [4, 7, 16, 21]. Approximately 80 patients presented with VS in our otorhinolaryngology department between 2012 and 2013. Among these were five cases of intralabyrinthine schwannomas. Intralabyrinthine schwannomas therewith accounted for 6 % of all VS so that the incidence was unexpectedly high. As limitation, however, we must state that in consideration of the low number of subjects, conclusions must be drawn with caution and a precise incidence cannot be given.

In summary, patients with intralabyrinthine schwannomas may present with clinical symptoms similar to patients suffering from other inner ear disorders, like delayed endolymphatic hydrops, and may also have similar findings in audiovestibular function tests. With the differential diagnosis of intralabyrinthine schwannoma in mind, high-resolution MRI should be conducted for all unclear cases of sudden or progressive asymmetric hearing loss. Furthermore, locally enhanced MRI for the detection of endolymphatic hydrops should be considered.

Conclusion

-

Intralabyrinthine schwannomas have a relatively long diagnostic delay.

-

The differential diagnosis of intralabyrinthine schwannoma should be kept in mind when evaluating patients with audiovestibular symptoms.

-

A similar clinical course and similar audiovestibular function test results may be found in patients with delayed endolymphatic hydrops.

-

High-resolution MRI of the inner ear can help establish a definite diagnosis in both cases.

References

Bernstein M, Berger MS (2008) Neuro-Oncology. The essentials. Thieme, New York

Birzgalis AR, Ramsden RT, Curley JW (1991) Intralabyrinthine schwannoma. J Laryngol Otol 105:659–661

Fiorino F, Pizzini FB, Beltramello A, Barbieri F (2011) MRI performed after intratympanic gadolinium administration in patients with Ménière’s disease: correlation with symptoms and signs. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268(2):181–187

Green JD Jr, McKenzie JD (1999) Diagnosis and management of intralabyrinthine schwannomas. Laryngoscope 109:1626–1631

Gürkov R, Flatz W, Louza J, Strupp M, Krause E (2011) In vivo visualization of endolyphatic hydrops in patients with Meniere’s disease: correlation with audiovestibular function. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268:1743–1748

Gürkov R, Flatz W, Louza J, Strupp M, Ertl-Wagner B, Krause E (2012) In vivo visualized endolymphatic hydrops and inner ear functions in patients with electrocochleographically confirmed Ménière’s disease. Otol Neurotol 33:1040–1045

Jia H, Marzin A, Dubreuil C, Tringali S (2008) Intralabyrinthine schwannomas: symptoms and managements. Auris Nasus Larynx 35:131–136

Kamei T (2004) Delayed endolymphatic hydrops as a clinical entity. Int Tinnitus J 10:137–143

Kennedy RJ, Shelton C, Salzman KL, Davidson HC, Harnsberger HR (2004) Intralabyrinthine schwannomas: diagnosis, management, and a new classification system. Otol Neurotol 25:160–167

Montague ML, Kishore A, Hadley DM, O’Reilly BF (2002) MR findings in intralabyrinthine schwannomas. Clin Radiol 57:355–358

Nadol JB, Weiss AD, Parker SW (1975) Vertigo of delayed onset after sudden deafness. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 84:841–846

Naganawa S, Nakashima T (2014) Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops with MR imaging in patients with Ménière’s disease and related pathologies: current status of its methods and clinical significance. Jpn J Radiol 32:191–204

Nakashima T, Naganawa S, Sugiura M et al (2007) Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops in patients with Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope 117:415–420

Neff BA, Willcox TO Jr, Sataloff RT (2003) Intralabyrinthine schwannomas. Otol Neurotol 24:299–307

Rosahl S (2009) Acoustic neuroma: treatment or observation? Dtsch Arztebl Int 106:505–506

Salzman KL, Childs AM, Davidson HC, Kennedy RJ, Shelton C, Harnsberger HR (2012) Intralabyrinthine schwannomas: imaging diagnosis and classification. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 33:104–109

Schuknecht HF (1976) Pathophysiology of endolymphatic hydrops. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 212:253–262

Schuknecht HF (1978) Delayed endolymphatic hydrops. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 87:743–748

Schuknecht HF, Suzuka Y, Zimmermann C (1990) Delayed endolymphatic hydrops and its relationship to Meniere’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 99:843–853

Seo YJ, Kim J, Choi JY, Lee WS (2013) Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops and correlation with audio-vestibular functional testing in patients with definite Meniere’s disease. Auris Nasus Larynx 40(2):167–172

Tieleman A, Casselman JW, Somers T, Delanote J, Kuhweide R, Ghekiere J, De Foer B, Offeciers EF (2008) Imaging of intralabyrinthine schwannomas: a retrospective study of 52 cases with emphasis on lesion growth. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29:898–905

Van Abel KM, Carlson ML, Link MJ, Neff BA, Beatty CW, Lohse CM, Eckel LJ, Lane JI, Driscoll CL (2013) Primary inner ear schwannomas: a case series and systematic review of the literature. Laryngoscope 123:1957–1966

Wolf JS, Mattox DE (1999) Imaging quiz case 2. Intralabyrinthine schwannoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125:107–109

Wolfson RJ, Leiberman A (1975) Unilateral deafness with subsequent vertigo. Laryngoscope 85:1762–1766

Wu Q, Dai C, Zhao M, Sha Y (2016) The correlation between symptoms of definite Meniere’s disease and endolymphatic hydrops visualized by magnetic resonance imaging. Laryngoscope 126(4):974–979

Zou J, Pyykkö I, Bjelke B, Dastidar P, Toppila E (2005) Communication between the perilymphatic scalae and spiral ligament visualized by in vivo MRI. Audiol Neurotol 10:145–152

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

C. Jerin, E. Krause, B. Ertl-Wagner and R. Gürkov declare that they have no competing interests. This study was supported by the Federal German Ministry of Education and Research (grant No. 01EO0901).

The accompanying manuscript does not include studies on humans or animals perfomed by any of the authors. Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

The supplement containing this article is not sponsored by industry.

Additional information

Redaktion

P.K. Plinkert, Heidelberg

B. Wollenberg, Lübeck

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jerin, C., Krause, E., Ertl-Wagner, B. et al. Clinical features of delayed endolymphatic hydrops and intralabyrinthine schwannoma. HNO 65 (Suppl 1), 41–45 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-016-0199-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-016-0199-6

Keywords

- Vestibular schwannoma

- Sensorineural hearing loss

- Labyrinth

- Vertigo

- Tinnitus

- Delayed endolymphatic hydrops

- Intralabyrinthine schwannoma