Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to compare the results of immediate and delayed percutaneous sacroiliac screws surgery for unstable pelvic fractures, regarding technical results and complication rate.

Design

Retrospective study.

Setting

The study was conducted at the Soroka University Medical center, Beer Sheva, Israel, which is a level 1 trauma Center.

Patients

108 patients with unstable pelvic injuries were operated by the orthopedic department at the Soroka University Medical Center between the years 1999–2010. A retrospective analysis found 50 patients with immediate surgery and 58 patients with delayed surgery. Preoperative and postoperative imaging were analyzed and data was collected regarding complications.

Intervention

All patients were operated on by using the same technique—percutaneous fixation of sacroiliac joint with cannulated screws.

Main outcome measurements

The study’s primary outcome measure was the safety and quality of the early operation in comparison with the late operation.

Results

A total of 156 sacroiliac screws were inserted. No differences were found between the immediate and delayed treatment groups regarding technical outcome measures (P value = 0.44) and complication rate (P value = 0.42).

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated that immediate percutaneous sacroiliac screw insertion for unstable pelvic fractures produced equally good technical results, in comparison with the conventional delayed operation, without additional complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic fractures are considered a treatment challenge for every orthopedic surgeon and traumatologists. These injuries are usually the result of high energy trauma (MVA’s, falls from height, crush injuries, etc.) and may be accompanied with major bleeding alongside the skeletal injury [1, 2].

Whenever a patient is suspected of suffering a pelvic injury, he must first be treated according to the ATLS protocol, and the pelvis must be stabilized in order to minimize pain and bleeding. The primary stabilization usually takes place in the ER by tying the pelvis with a sheet, a pelvic binder, or by using an external fixator or a C-clamp, which should be replaced as soon as possible. After completion of the primary survey of the ATLS protocol, X-ray of the pelvis should be taken in the order to look for a pelvic fracture and to try and estimate its severity. Only after the major life saving actions are completed other examinations such as CT scans can take place, and the treatment plan for the pelvis can be set [3].

The pelvic binder used as a primary emergent pelvic stabilizer helps to stabilize the anterior part of the pelvic ring. Several techniques enables us to stabilize and fixate the posterior pelvic ring as well, the most common of which are the posterior sacroiliac screws—inserted through the iliac bones to the body of the S1 vertebra [4]. Since the beginning of 1990’s early reports highlighted the percutaneous insertion of the sacroiliac screws, allowing for lesser exposure of soft tissues around the pelvis [5].

The percutaneous technique primarily introduced by Routt et al. [6], has other advantages aside from delicate soft tissue handling, such as diminished blood loss and lower perioperative infection rates. The described complications of the percutaneous technique are mechanical failure of the fixation, misplacement of the screws, neurologic injury, infection and inaccurate reconstruction of the posterior pelvic ring [7]. The operation is usually being held between 24 and 48 h from time of injury, but as more experience is gained by pelvic and trauma surgeons attempts are being made to stabilize and fix the pelvis on an immediate basis [8], assuming the general condition of the patient enables it.

This study set out to find differences in reduction quality and complication rate between two groups of patients who suffered an unstable pelvic fracture and were treated with percutaneous sacroiliac screws—those who were treated immediately on arrival compared with those who were treated after 24 h.

Patients and methods

Between January 1st 1999 and December 31st 2010, 108 patients with unstable pelvic fractures were operated on by the surgeons of Orthopedic Trauma Unit at the Soroka University Medical Center in Beer Sheva Israel, using closed reduction and percutaneous insertion of cannulated sacroiliac screws.

Data collection commenced only after formal approval from the local Helsinki Committee was acquired. The data was collected retrospectively from the hospital archives.

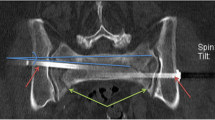

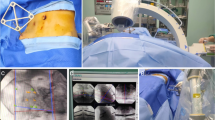

Patients and treatment protocol (Fig. 1)

All patients were initially treated in the trauma bay by a joined trauma team led by a general surgeon and an orthopedic surgeon, according to the ATLS protocol. Every pelvic fracture recognized at that stage was primarily stabilized using a binding sheet and traction as needed. All patients had pelvic X-ray done in the trauma bay and later on a CT scan for a more accurate estimation of the injury, excluding the hemodynamically unstable patients who were rushed to the operating room straight after the primary survey.

Immediate pelvic fixation with posterior sacroiliac screws and anterior plating. a Pre-op 3D CT reconstruction demonstrating a Tile C unstable pelvic fracture. b Post operative 3D CT reconstruction demonstrating the reduced pelvis. c–e Fluoroscopic views demonstrating the reduced pelvis with the posterios sacroiliac screws and the anterior plate

All the patients in the study suffered a closed fracture of the pelvis, with varying degrees of severity.

Stability of the pelvic ring was determined according to Tile’s method [9] which separates between stable, partially stable and unstable pelvic fractures (Table 1). The indications for surgery were unstable and partially stable fractures (Tile B, C) needing posterior pelvic stabilization. Immediate fixation was done under two main indications—first, for hemodynamically unstable patients due to their pelvic fracture we used the reduction and fixation as a resuscitative aid [8], and second—for hemodynamically stable patients that we estimated that could profit from early fixation in the sense of pain reduction, easy nursing and earlier rehabilitation.

All patients were operated on by a team led by a single surgeon (A.K), in a supine position on a radiolucent table while using a portable C-arm fluoroscopy machine. Reduction of the sacroiliac joint was achieved either by closed manipulation, by use of an external fixator and sometimes with the sacroiliac screw itself. Open reduction was not required (Fig. 1).

All Patients received preoperative antibiotic treatment and postoperative anticoagulation with SC Enoxaperin.

After surgery the patients were treated in the orthopedic department or the ICU according to their general condition and most of them were discharged to a rehabilitation center afterwards. Most patients continued their follow-up visits with the orthopedic trauma team in the outpatients’ clinics of the hospital.

Imaging analysis

Pre-operative X-ray and CT scan were obtained as mentioned above. After surgery X-rays were taken in different angles (AP, Inlet and Outlet views) and a second CT scan was obtained to verify the exact position of the screws and to estimate the quality of reduction.

We reviewed all the pre and postoperative imaging studies of the patients enrolled in the study. Each fracture was classified after Tile [9] preoperatively, and the quality of reduction was measured according to the system of Matta and Tornetta [10] on the postoperative CT scan.

Statistical analysis

The case information was coded and stored in a Microsoft Office Excel file and transferred into the SPSS 17.0 program. The data was first analyzed using descriptive statistics (using the appropriate central and distribution indices).

Comparison between groups was performed using the Pearson Chi square test for nominal variables Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables (when applicable).

Comparison of quantitative variables was done with the parametric t test when appropriate (e.g., Summary value of the SF-36); for a-parametric tests, we used the Mann–Whitney test. Correlations were measured with Pearson’s correlation for parametric variables and Spearman’s correlation for a-parametric variables. Statistical significance was considered when P value was <0.05.

Sample size calculation

In order to try and evaluate the number of patients needed to be investigated we have used a sample size computer program (WINPEPI), using the compare function, under the following assumptions: α = 0.05, β = 0.8, OR of 3.5 or more was considered statistically significant. It was evaluated the success rate in the control group will be at least 0.7. Under these assumptions each group needed at least 42 patients within, or after continuity correction at least 45 patients in each group or 90 patients at all.

Results

Demographic results (Table 2)

108 patients were treated with percutaneous insertion of sacroiliac screws in the Soroka University Medical Center between the years 1999–2010. 58 patients were operated after 24 h had past since their arrival and 50 patients were operated immediately on arrival, of which 32 (64 %) were men and 18 (36 %) women. The mean age in the immediate group was 37.56 (±20.12) while in the late group it was 31.43 (±13.68) (P value = 0.086).

A total of 156 sacroiliac screws were inserted. The average number of screws per patient was 1.5 (±0.7) in the immediate group, and 1.4 (±0.53) in the late group, with no statistical difference between them (P value = 0.387).

The comparison of the average number of hospitalization days between the two groups shows that the immediate group had a longer hospitalization period of 30.29 days (±27.22) with 13 days of them in the ICU (±21.04) while the late group had only 21.37 (±19.03) and 9.55(±10.750) in concordance (P value = NS). No significant statistical difference was found in the ISS score between the two groups as well (P value = 0.295).

Roentgenographic results (Fig. 2)

According to Matta and Tornetta’s criteria for analyzing the roentgenographic results [10] of sacroiliac joint fixation, an excellent result (displacement <4 mm) was achieved with 93 patients, good results (displacement between 4 and 10 mm) were achieved with 8 patients and fair result (displacement between 10 and 20 mm) with only 5 patients. No poor results were achieved (displacement >20 mm). No significant differences were found upon comparing the roentgenographic results between the early and the late groups (P value = 0.44).

Complications

During the follow-up period three patients died from reasons unrelated to their initial trauma or pelvic surgery. Eight patients (7.4 %) suffered complications after the surgical treatment: two patients suffered from post-operative infection, two patients were spotted to have penetration of the screws into the S1 foramina in the post-operative CT scan which mandated their removal. Four patients required screw removal due to post-operative pain after which the pain resolved. We didn’t observe any loosening of implants or loss of reduction in any of our patients. No significant difference in complication rates was found between the early and late groups (P value = 0.42).

Discussion

The modern era of pelvic surgery is considered relatively young in orthopedic treatment history, beginning in the early 70’s of the last century with the publications of Judet and Leturnel [11]. Scientific researches analyzing the long term results of these surgeries began appearing only 20 years later—in the early 90’s of the last century and for the first time focused not only on the technical-roentgenographic result of the surgery but rather on the functional result and the quality of life of these patients [12]. With the development of new concepts such as Damage Control in Orthopedic Trauma, debates were held regarding the correct timing of these surgeries, and studies comparing early versus late treatment of pelvic fractures began to appear [11, 13].

Surgical techniques for treating pelvic fractures also gradually evolved through the years. While in the early days these surgeries were done mainly by using open reduction and fixation techniques, the early 90’s signified a vast change of perspective, when Routt [14] presented the percutaneous technique for sacroiliac fixation, which since then became popular worldwide and actually revolutionized the treatment approach to these fractures. Recently, reports are emerging of usage of this percutaneous technique as a resuscitation aid in hemodynamically unstable patients with pelvic fractures [8].

In this study we present the treatment outcome of patients with unstable pelvic fractures at the Soroka University Medical Center in Beer-Sheva, Israel, between the years 1999–2010. We examined the results from a technical point of view (quality of reduction and complication rate) and compared treatment results between patients who were treated on arrival and after 24 h.

Technical point of view

A number of articles demonstrate a direct link between the quality of reduction of the pelvic ring and the functional outcome of the surgery [15]. The need to estimate the amount of the fracture’s primary displacement and the quality of reduction achieved has led to the development of several radiological measuring systems, as described in the article by Mataliotakis and Giannoudis [15]. In fact more than 5 different systems were developed with the most prevalent one is the one developed by Matta and Tornetta [16], which divides the reduction quality into 4 stages—excellent (displacement of 0–4 mm), good (displacement of 4–10 mm), fair (displacement of 10–20 mm) and poor (displacement of more than 20 mm).

In their classical work Matta and Tornetta [16] described long term results of 46 patients, with 36/46 excellent result, 9/36 good result and only 3/36 of the patients with fair result. Osterhoff et al. [17] reviewed the results of 39 patients after posterior fixation of unstable pelvic injuries and demonstrated excellent result in 61 %, good result in 35 % and fair result in 4 % of their patients. Schweitzer et al. [18] demonstrated satisfactory result (displacement <10 mm by their standard) with 69/73 of their patients. In the present study we used Matta and Tornetta’s [16] scoring system and found satisfactory results in 103/108 of our patients—an outcome that lines up with other worldwide leading articles. On top of that—we found no differences in the reduction quality between our early and late groups, similar to the findings of Zamzam et al. [19] in his work on surgical timing.

Complications

The percutaneous technique of sacroiliac joint fixation significantly lowered the rates of complications related to pelvic surgery, mostly regarding soft tissue infections and bleeding [20], although some complications still exist, mainly nerve injury due to screw misplacement, hardware loosening, local infections and inaccurate reduction.

Schweitzer et al. [18] present relatively low complication rates with 1 % infections, 6 % post-operative neurological injury and 1 % of screw misplacement throughout their cases. A number of other articles demonstrate similar results with infection rates of 0–1 %, screw related neurological injury of 0–8 % and screw misplacement in the range of 2–12 % [20–23]. Our current study demonstrated equally good results with 1.85 % infection rate, 5.55 % of neurological injuries and 1.85 % of screw misplacement.

When we compared the early and late treatment groups we found no significant differences in complication rates. Similarly, we found no differences in the average number of hospitalization days, ICU hospitalization days and ISS score. These results correspond to the results of Palsier et al. [24] which also found no differences in complication rates between the two groups. Other studies, such as that of Connor et al. [25] showed significantly more complications with the late group, mainly pulmonary complications. Palsier et al. [24] explained their indifference and claimed that the ISS of the early group was higher, which meant the injury was more significant, hence, creating a bias. In our study, no difference was found in the ISS between the two groups so the results can’t be explained the same way.

Early versus late surgery

The definition of “early” and “late” surgery is a matter of debate. Some studies define “early treatment” as one that is given up to 8 h from the patient’s arrival, while others define a 24–72 h window, and there are even studies who use a week as their standard. The definition of “late surgery” varies to the same amount from as early as 2 weeks and up to 3 months post injury [11, 13, 25]. We chose to use the 24 h mark for separation between the early and late groups and found no differences between the groups in all the parameters examined—roentgenographic results, complications, hospitalization days, scores and days in ICU.

Katsoulis and Giannoudis [11] conducted a thorough MEDLINE search and found only five articles comparing early versus late results of pelvic surgeries. Their analysis shows that early treatment of pelvic fractures yields better results with lower complication rates. They state that the problematic definition of early and late surgery and the inequality in post surgery outcome assessment methods, makes it very hard to compare different studies but generally—they all point out to the same conclusions—early surgery is better than late one. Similar conclusions were drawn by the AOTrauma study group reviewing the same issues [13]. Our study didn’t show superiority of the early surgery but it did demonstrate that it was as safe as the late one, without additional complications.

Study limitations

-

Since this is a retrospective study, no conclusion regarding causality could be drawn. Having said that—all the studies dealing with the same issues are also retrospective. One may raise an ethical question as to the possibility of randomization in acute pelvic injuries since these patients either need surgery or don’t need surgery.

-

This study was conducted only in the Soroka University Medical Center, and most of the surgeries were done by a single surgeon. These facts make the generalization of the conclusions more problematic.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates and proves that immediate percutaneous fixation of unstable pelvic fractures achieves clinical and radiographic results that are comparable to late surgery, without raising the complication rate. We therefore, recommend on conducting this procedure as soon as possible assuming that the surgical team and facility are ready and qualified enough.

References

Routt ML Jr, Nork SE, Mills WJ. High-energy pelvic ring disruptions. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33(1):59–72.

Kregor PJ, Routt ML Jr. Unstable pelvic ring disruptions in unstable patients. Injury. 1999;30(Suppl 2):B19–28.

Michael D. Stove., Keith A. May., James F. Kellam, . Pelvic Ring Disruptions. In: Bruce D. Browner editor. Skeletal Trauma. 4th ed, 3rd sect., chap. 36. Elsevier’s Health Sciences, Philadelphia; 2008.

Tile M. Acute pelvic fractures: II. Principles of management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4(3):152–61.

Routt ML Jr, Nork SE, Mills WJ. Percutaneous fixation of pelvic ring disruptions. Clin Orthop. 2000;375:15–29.

Routt M, Meier M, Kregor P. Percutaneous iliosacral screws with the patient supine technique. Oper Techn Orthop. 1993;3:35–45.

Routt ML Jr, Simonian PT, Mills WJ. Iliosacral screw fixation: early complications of the percutaneous technique. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;8:584–9.

Gardner MJ, Routt ML Jr. The antishock iliosacral screw. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:86–9.

Tile M. Acute pelvic fractures: I. Causation and classification. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4:143–51.

Matta JM, Tornetta P. Internal fixation of unstable pelvic ring injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:129–40.

Katsoulis Efstathios, Giannoudis PV. Impact of pelvic fixation on functional outcome. Injury. 2006;37:1133–42.

Oliver CW, Twaddle J, et al. Outcome after pelvic ring fractures: evaluation using the medical outcomes short form SF-36. Injury. 1996;27:635–41.

Pelvic ring fractures—early versus delayed fixation. Buckley Rick—Editor in chief. Orthopedic Trauma Directions 1/11, Vol 9, No 1, January 2011. Published by AO Foundation, Switzerland.

Routt ML Jr. Supine positioning for the placement of percutaneous sacral screws in complex posterior pelvic ring trauma. Orthop Trans. 1992;16:220.

Mataliotakis GI, Giannoudis PV. Radiological measurements for postoperative evaluation of quality of reduction of unstable pelvic ring fractures: advantages and limitations. Injury. 2011;42:1395–401.

Tornetta P, Matta J. Outcome of operatively treated unstable posterior pelvic ring fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:186–93.

Osterhoff G, Ossendorf C, et al. Posterior screw fixation in rotationally unstable pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 2011;42:992–6.

Schweitzer D, Zylberberb A, et al. Closed reduction and iliosacral percutaneous fixation of unstable pelvic ring fractures. Injury. 2008;39:869–74.

Zamzam MM. Unstable pelvic ring injuries—outcome and timing of surgical treatment by internal fixation. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1670–4.

Routt ML Jr, Kregor PJ, Simonian PT, et al. Early results of percutaneous iliosacral screws placed with the patient in the supine position. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9:207–14.

Shuler TE, Boone DC, Gruen GS, et al. Percutaneous iliosacral screw fixation: early treatment for unstable posterior pelvic ring disruptions. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;38:453–8.

Tonetti J, Carrat L, Lavallee S, et al. Percutaneous iliosacral screw placement using image guided techniques. Clin Orthop. 1998;354:103–10.

Van den Bosch EW, Van Zwienen CM, Van Vugt AB. Fluoroscopic positioning of sacroiliac screw in 88 patients. J Trauma. 2002;53:44–8.

Plaisier BR, Meldon SW, Super DM, Malangoni MA. Improved outcome after early fixation of acetabular fractures. Injury. 2000;31(2):81–4.

Connor GS, McGwin J Jr, MacLennan PA, et al. Early versus delayed fixation of pelvic ring fractures. Am Surg. 2003;69(12):1019–23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding were received for the current study.

Conflict of interest

We Asaf Acker, Zvi Perry, Shlomo Blom, Gad Shaked and Amir Korngreen declare we have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards statement

We hereby declare that all human and animal studies have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore, been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Acker, A., Perry, Z.H., Blum, S. et al. Immediate percutaneous sacroiliac screw insertion for unstable pelvic fractures: is it safe enough?. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 44, 163–169 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-016-0654-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-016-0654-9