Abstract

Objectives

This study examines the relationship between neighbourhood green space, the neighbourhood social environment (social cohesion, neighbourhood attachment, social contacts), and mental health in four European cities.

Methods

The PHENOTYPE study was carried out in 2013 in Barcelona (Spain), Stoke-on-Trent (United Kingdom), Doetinchem (The Netherlands), and Kaunas (Lithuania). 3771 adults living in 124 neighbourhoods answered questions on mental health, neighbourhood social environment, and amount and quality of green space. Additionally, audit data on neighbourhood green space were collected. Multilevel regression analyses examined the relation between neighbourhood green space and individual mental health and the influence of neighbourhood social environment.

Results

Mental health was only related to green (audit) in Barcelona. The amount and quality of neighbourhood green space (audit and perceived) were related to social cohesion in Doetinchem and Stoke-on-Trent and to neighbourhood attachment in Doetinchem. In all four cities, mental health was associated with social contacts.

Conclusions

Neighbourhood green was related to mental health only in Barcelona. Though neighbourhood green was related to social cohesion and attachment, the neighbourhood social environment seems not the underlying mechanism for this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is growing evidence that neighbourhood green space is beneficial for mental health (Alcock et al. 2014; Di Nardo et al. 2012; Hartig et al. 2014; Van den Berg et al. 2015). The neighbourhood social environment has been suggested to be one of the mechanisms. The presence of green, such as trees or vegetation increases the attractiveness of common spaces in the neighbourhood, thereby potentially increasing their use (Coley et al. 1997; Kuo et al. 1998), and facilitating informal social contacts between community members (Hartig et al. 2014; Kuo et al. 1998). Social contacts are health promoting; for instance through the social support they can offer (Cohen 2004). By facilitating social contacts, neighbourhood green can contribute to the development of neighbourhood social cohesion, i.e. the connectedness and solidarity among community members, which has proven to benefit people’s health (Di Nardo et al. 2012; Kawachi and Berkman 2000). Furthermore, having green areas in the neighbourhood increases the attractiveness of the living environment, thereby enhancing people’s attachment to the physical neighbourhood environment (Di Nardo et al. 2012). Place attachment helps to create group identity, which translates into a general sense of well-being (Brown et al. 2003) and has been associated with reduced loneliness and better mental health (Hagerty and Williams 1999; Pretty et al. 1994).

The neighbourhood social environment as a mechanism for the impact of neighbourhood green space on mental health has received some research attention in the past years. Some studies found that social cohesion mediated the relation between green space and mental health (de Vries et al. 2013; Sugiyama et al. 2008), while others did not (Triguero-Mas et al. 2015). Lack of social support and feelings of loneliness were reported to mediate the relationship between green space and mental health (Maas et al. 2009), but not social contacts (Maas et al. 2009; Sugiyama et al. 2008). Inconsistencies between studies might be explained by different operationalisations of the social environment (e.g. social cohesion, individual social contacts, loneliness). It is also possible that the relationship between neighbourhood green, social environment and mental health differs across cultures (Hartig et al. 2014). For instance, in more individual oriented cultures, green space might be more important for the facilitation of social interactions than in more collectivist cultures where communal life is already more common.

In the current study, we investigate the relationship between neighbourhood green space, neighbourhood social environment, and mental health in four European cities to examine if the social environment might be one of the mechanisms between neighbourhood green and mental health. The following research questions are addressed: is neighbourhood green space related to the neighbourhood social environment in four European cities? Are the neighbourhood social environment and neighbourhood green space related to mental health in these cities?

This study uses a range of social environment measures (social cohesion, neighbourhood attachment, and individual social contacts) to examine if the associations depend on the operationalisation of social environment. Our green measures comprise both the amount and quality of neighbourhood green, to accommodate the increasing evidence stressing the importance of quality of green space and its impact on health (Francis et al. 2012; Hartig et al. 2014; Van Dillen et al. 2012). Furthermore, objective audit and subjective green measures are used as they may capture different aspects of greenness i.e. more emotional aspects with subjective measures and more tangible aspects with objective measures (Francis et al. 2012). These aspects may relate to the social environment characteristics and mental health differently (Leslie et al. 2010).

Methods

Study background

This EU-funded PHENOTYPE study examined the health effects of the natural environment and its underlying mechanisms. A cross-sectional survey was carried out from May to October 2013 in four cities across Europe: Stoke-on-Trent (United Kingdom), Doetinchem (Netherlands), Barcelona (Spain), and Kaunas (Lithuania) (Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 2014).

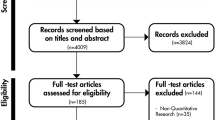

Study population and data collection

In each city, 30 neighbourhoods varying in neighbourhood green space and socioeconomic status (SES) were selected (see Table 1 for a description of the neighbourhoods). Survey data were collected using face-to-face interviews, with the exception of Lithuania, where data were collected with a postal questionnaire. Around 1000 adults aged 18–75 years, were interviewed per city (n = 3947, overall response rate 20%) across 124 neighbourhoods. For further details on the data collection see Online Resource 1. We selected respondents with complete data for the indicators of interest, providing a sample of 3771 respondents in 124 neighbourhoods (96% of the study population).

Additionally, in each neighbourhood an audit was carried out to assess the amount and quality of green space. For each neighbourhood a purposeful sample of streets was selected, ensuring that rare, but important, features of the neighborhood were included (e.g. parks). To do so, we divided each neighbourhood into more or less homogeneous sub-areas by means of land use maps in combination with local knowledge of the areas. Per sub-area, several streets were selected and combined into a route that was inspected by two trained auditors (in a small number of cases by one auditor) in a systematic way, using a form containing closed questions.

Measures

Mental health

Mental health was measured using the mental health inventory (MHI-5) (Ware Jr and Sherbourne 1992). MHI-5 assesses nervousness and feelings of depression in the past month, with answers ranging from ‘all the time’ to ‘never’ on a six-point scale. Sum scores of the five answers were transformed into a scale from 0 to 100 (Ware Jr et al. 1995), with higher scores reflecting better mental health. The scale has proven to be of good validity and reliability (Ware Jr 2000).

Neighbourhood green space

Audit amount and quality of neighbourhood green space

Amount of neighbourhood green space was based on six items containing information about the fraction of visible gardens, garden size, the arrangement of the gardens, number of trees, size of public green spaces, and size of public blue spaces (Cronbach’s alpha 0.66). Quality of neighbourhood green space was derived from one question, answered by the auditors: ‘what is your general impression of the quality of the green space in this neighbourhood’? Answers ranged from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive).

Indicators were standardised using Z-scores, calculated for each city separately. This way, neighbourhood green was compared between the neighbourhoods within one city and not across all cities, allowing the examination of the relative effect of green space on mental health.

Subjective amount and quality of neighbourhood green space

Subjective amount of neighbourhood green space was measured by asking the respondents: ‘How would you describe your neighbourhood in terms of green space’, with answers on a five-point Likert scale from ‘not green at all’ (1) to ‘very green’ (5). Subjective quality of neighbourhood green space was measured by asking: ‘Overall, in your neighbourhood, how satisfied are you with the quality of the green/blue environment?’ Answers ranged on a five-point Likert scale, with a higher score meaning more satisfaction with the quality.

We conducted ecometric analyses to calculate the average perception of neighbourhood green space (see Online Resource 2 for a description of the ecometric analysis) (Raudenbush and Sampson 1999). This way, we can include subjective assessments of neighbourhood green space, while avoiding ‘same-source bias’ (also measured at the same-time) (de Jong et al. 2011; Wheaton et al. 2015). Ecometric average scores were calculated (stratified by city) and standardised into country-specific Z-scores.

We use the term neighbourhood green space for our natural environment measures, because the audit showed that the neighbourhood natural environment consisted foremost of green elements and because mainly green space is relevant for the social interaction mechanism.

Social environment

We measured three aspects of the social environment.

Social cohesion constructed by summing the answers to five statements from the social cohesion and trust scale (Sampson et al. 1997): ‘People are willing to help their neighbours’, ‘This is a close-knit neighbourhood’, ‘People in this neighbourhood can be trusted’, ‘People in this neighbourhood generally don’t get along with each other’ (reversed), and ‘People in this neighbourhood do not share the same values’ (reversed). Using a 5-point Likert scale, answers ranged on from ‘totally disagree’ to ‘totally agree’. Negatively stated items were recoded so that a higher score reflected higher levels of social cohesion (Cronbach’s alpha 0.76).

Neighbourhood attachment measured by summing the answers to three statements: ‘I feel attached to this neighbourhood’, ‘I feel at home in this neighbourhood’, and ‘I live in a nice neighbourhood were people have a sense of belonging’, using a 5-point Likert scale, answers ranged on from ‘totally disagree’ to totally agree. A higher score reflected stronger neighbourhood attachment (Cronbach’s alpha 0.80).

Social contacts respondents were asked how often they had contact with their neighbours. Answers were: ‘daily’, ‘at least once a week’, ‘1–3 times per month’, ‘less than once a month’, and ‘seldom or never’. Social contacts was dichotomised into ‘at least once a week’ versus ‘less often’ for the analyses with social contacts as outcome measure.

Similar to the subjective green measures, ecometric analyses were conducted to calculate the neighbourhood average scores of social cohesion and neighbourhood attachment (see Online Resource 2). Social contacts were included at the individual level.

The correlations between the neighbourhood characteristics (Online Resource 3) show that the audit and perceived green measures were moderately related, suggesting that these indicators measured different aspects of neighbourhood green space.

Confounders

Individual control variables in all analyses were sex, age (in years), highest achieved educational level (primary school /no education; secondary school/further education; university degree or higher), nationality (country nationality; other), employment status (fulltime employed; other), household composition (with children under 12 years; other), and homeownership (yes; no). Neighbourhood socioeconomic status (SES) (low; intermediate; high; based on country-specific data, see Online Resource 1) was included as a neighbourhood level confounder. See Table 2 for the descriptive statistics.

Analyses

Multilevel linear and logistic regression analyses were performed, with individuals at level one, neighbourhoods at level two, and city at level three. City was included as level to adjust for systematic differences in the intercept between the four cities, i.e. city differences caused by, for instance, policy differences. The green variables were allowed to have a different effect (slope) on social environment and health for every city, by creating a separate green indicator variable for every city (green indicator X city-dummy (1 = belongs to this city, 0 = does not belong to this city)). All four city green variables are added to the model (Weisberg 2005).

First, multilevel models assessed the association between neighbourhood green space and individual level social contacts in the four cities. Ecological models at the neighbourhood level assessed the associations between neighbourhood green, social cohesion, and neighbourhood attachment, respectively. Next, we examined the associations between social cohesion, neighbourhood attachment, social contacts and mental health in the four cities, while adjusting for green space. Finally, we examined the associations between green space at the neighbourhood level and mental health in the four cities. The analyses with the subjective neighbourhood level green measures were also adjusted for the individual perception of neighbourhood green space, to distinguish the contextual health effect of green space from the individual level effect. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3.

Results

Neighbourhood green space and the social environment

More cohesive neighbourhoods were greener and had better quality green space in Doetinchem (perceived and audit) and in Stoke-on-Trent (perceived amount; perceived and audit quality) (Table 3). In Barcelona and Kaunas, neighbourhood-level green space was not related to neighbourhood social cohesion.

Stronger neighbourhoods attachment was found in greener neighbourhoods (perceived) and neighbourhoods with better quality green space (audit and perceived) in Doetinchem (Table 3). Better perceived quality of neighbourhood green was associated with stronger neighbourhood attachment in Barcelona and Stoke-on-Trent as well.

Neighbourhood green space was not associated with social contacts in any of the cities.

Social environment and mental health

Residents living in neighbourhoods with more social cohesion or with stronger neighbourhood attachment reported better mental health only in Stoke-on-Trent, not in the other cities (Table 4). Having more frequent social contacts was associated with better mental health consistently in all four cities.

Neighbourhood green space and mental health

In Barcelona, a higher amount of neighbourhood green (audit) was associated with better mental health (Table 4). In the other three cities, neighbourhood green space was not associated with mental health.

The social environment as possible mechanism

In Barcelona, we found no associations between neighbourhood green space and (one aspect of) the social environment (Table 3) and between the (same aspect of the) social environment and mental health (Table 4). In the other cities, we found no associations between neighbourhood green space and mental health (Table 4). Therefore, we found no indications that the social environment could be an underlying mechanism between neighbourhood green space and mental health.

Discussion

Greener neighbourhoods and neighbourhoods with better quality green space were more cohesive and had higher levels of neighbourhood attachment in Doetinchem and Stoke-on-Trent. More neighbourhood cohesion and stronger neighbourhood attachment were associated with better mental health in Stoke-on-Trent only. Only in Barcelona, however, the neighbourhood green space was associated with better mental health, but there, we found no indications that the social environment could be the underlying mechanism.

Study limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study prevents conclusions about the causality of the relationships (Galster 2008). We therefore did not implement statistical tests for mediation, as mediation implies causal processes. Another limitation is the low response rate (see Online Resource 1), resulting in an underrepresentation of low educated people in all four cities. It is suggested that people with a low socioeconomic status (SES) may benefit more from neighbourhood green space than those with a high SES (Mitchell and Popham 2008). The underrepresentation of low educated people may therefore have resulted in an underestimation of the relationship between green space and mental health. Third, in Kaunas, there was no variation between neighbourhoods in neighbourhood attachment and, as pointed out by the low reliability scores of green space and social cohesion in Table 2, only little neighbourhood variation in case of the other neighbourhood measures (Hox 2010). Because of the low reliability scores, we excluded results from Kaunas based on the perception measures in the discussion of the implications. Finally, the neighbourhoods in Barcelona were considerably smaller in size compared to the other cities. This could have increased the chance that the Spanish neighbourhoods were more homogeneous in terms of the amount and quality of neighbourhood green space, which could have resulted in more precise audit assessment of the neighbourhood green space in Barcelona. We cannot rule out completely that a more precise audit assessment of the green space in Barcelona resulted in finding a relation between audit amount of green space and mental health there.

Neighbourhood green space and the social environment

Our study showed that green space at the neighbourhood level was related to the neighbourhood social environment. Our findings that related social cohesion consistently to neighbourhood green space in Doetinchem and Stoke-on-Trent strengthens the evidence on the influence of green space on the development of social cohesion. Furthermore, in line with Arnberger and Eder (2012) we report neighbourhood attachment to be consistently associated with neighbourhood green space in Doetinchem, as well as the subjective quality of neighbourhood green in Barcelona and Stoke-on-Trent. We found no evidence that neighbourhood green space is related to more contacts between neighbours, in line with Maas et al. (2009) Our findings corroborate the argument by Hartig et al. (2014) that physical neighbourhood characteristics, such as green space, influence other area characteristics, e.g. social cohesion, more easily than individual characteristics, e.g. individual social contacts.

Green space, social environment and the relation with mental health

Our finding that individual social contacts were associated consistently with better mental health, while social cohesion and neighbourhood attachment were related to better mental health in Stoke-on-Trent, UK exclusively, underlines the fact that the neighbourhood environment is in general less important for individual health than individual characteristics (Pickett and Pearl 2001). Despite of that, studying neighbourhood characteristics such as neighbourhood green is relevant as it can influence the health of many people, therewith contributing substantially to the health of the population.

We found only weak evidence for a relationship between neighbourhood green space and mental health. A study that used similar green data, i.e. audit information, reported no relation between the presence of green and general health (Dunstan et al. 2013), though another study reported that the amount of green was related to mental health (Van Dillen et al. 2012). We could only replicate this association between the amount of green space and mental health in Barcelona. The Barcelona neighbourhoods were considerably less green than the neighbourhoods in other cities (see Table 1). Possibly living in greener neighbourhoods in Barcelona is more strongly related to mental health than in other cities, because of the scarcity of green space in general. Another explanation for finding an association between green space and mental health in Barcelona only, is that especially nearby green space seems important for mental health (Kaplan 2001; Triguero-Mas et al. 2015; Van Dillen et al. 2012), as the Barcelona neighbourhoods were by far the smallest in this study. When we conducted post-hoc analysis using individual perception of neighbourhood green, assuming that the individual perception is based on nearby green space more than the neighbourhood average perception of green, we indeed found associations between green space and mental health in Doetinchem as well.

In our study, quality of neighbourhood-level green was not associated with mental health, which is in contrast with previous studies (Francis et al. 2012; Van Dillen et al. 2012). We used a crude measure for quality of green space. Possibly this measure was not specific enough to detect a relationship with mental health.

We found no indications that the neighbourhood social environment serves as a possible mechanism between neighbourhood green space and mental health. We either failed to find a relation between neighbourhood green space and mental health (i.e. Kaunas, Doetinchem, Stoke-on-Trent), or did not find associations between neighbourhood green space and (one aspect of) the social environment and between the (same one aspect of the) social environment and mental health (i.e. in Barcelona). In Barcelona, a highly urbanized city, restoration from daily stress might be a more relevant mechanism underlying the association between green space and mental health than the social environment. Unfortunately, we were unable to examine this hypothesis with the available PHENOTYPE dataset.

Comparison of the cities

There were marked differences between the cities with regard to the relevance of the neighbourhood environment for mental health. The Intra-Class Correlations of the cities (ICC), which estimates the proportion of variation in mental health between residents that is related to neighbourhood characteristics, reflects these differences. For example, in Doetinchem, the ICC was very low (0.51%) and both green space and the social neighbourhood characteristics were unrelated to mental health, in contrast with Stoke-on-Trent and Barcelona with ICCs of 8.51 and 6.71%, respectively. In Barcelona, this ICC reflected the relation between neighbourhood green space and mental health and in Stoke-on-Trent the neighbourhood social environment was related to mental health. The different findings across the cities might reflect geographical and cultural differences (Hartig et al. 2014). The differences could also reflect that, despite the use of identical measurements, data might still not be comparable due to cultural differences in the interpretation of survey questions and audit. The use of more objective measures, such as GIS data, could improve the comparability of the findings, but this might at the same time not be the environmental characteristics that have the biggest impact on mental health. Furthermore, more objective data on the quality of neighbourhood green or the social neighbourhood characteristics will be much more difficult to achieve. Future comparative studies should make efforts to also incorporate objective data to allow even better comparison between European settings.

Conclusion

Neighbourhood green and the neighbourhood social environment were related to one another in two cities, but did not translate into better mental health there. Neighbourhood green was related to mental health only in Barcelona, but there we found no indication that the neighbourhood social environment could be the underlying mechanism. Our study found no indications that improving neighbourhood green space could be a relevant public health policy, nor were there indications that health benefits of green space would occur through the improvement of the neighbourhood social environment. Future studies should use longitudinal data to further investigate the possibility of this mechanism. To improve the comparison between European settings, studies should try to incorporate objective measures of both green and the social environment.

Key points

-

The neighbourhood social environment has been suggested to be one of the mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effect of green space on health.

-

This study examines the relationship between neighbourhood green space, social cohesion, neighbourhood attachment, social contacts, and mental health in four European cities.

-

We find no evidence that the neighbourhood social environment could be the underlying mechanism between neighbourhood green space and mental health.

-

The relevance of this mechanism needs further investigation with longitudinal data and with more objective data to improve the comparison between European settings.

References

Alcock I, White MP, Wheeler BW, Fleming LE, Depledge MH (2014) Longitudinal effects on mental health of moving to greener and less green urban areas. Environ Sci Technol 48:1247–1255

Arnberger A, Eder R (2012) The influence of green space on community attachment of urban and suburban residents. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 11:41–49

Van den Berg M, Wendel-Vos W, van Poppel M, Kemper H, van Mechelen W, Maas J (2015) Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 14:806–816

Brown B, Perkins DD, Brown G (2003) Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: Individual and block levels of analysis. J Environ Psychol 23:259–271

Cohen S (2004) Social relationships and health American psychologist 59:676

Coley RL, Sullivan WC, Kuo FE (1997) Where does community grow? The social context created by nature in urban public housing Environment behavior 29:468–494

Di Nardo F, Saulle R, La Torre G (2012) Green areas and health outcomes: a systematic review of the scientific literature Italian. J Publ Health 7

de Vries S, van Dillen SM, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P (2013) Streetscape greenery and health: Stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc Sci Med 94:26–33

Van Dillen SM, de Vries S, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P (2012) Greenspace in urban neighbourhoods and residents’ health: adding quality to quantity. J Epidemiol Commun Health 66:e8–e8

Dunstan F, Fone DL, Glickman M, Palmer S (2013) Objectively measured residential environment and self-reported health: a multilevel analysis of UK census data. PloS One 8:e69045

Francis J, Wood LJ, Knuiman M, Giles-Corti B (2012) Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between public open space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc Sci Med 74:1570–1577

Galster G (2008) Quantifying the effect of neighbourhood on individuals: challenges, alternative approaches, and promising directions. Schmollers jahrbuch 128:7–48

Hagerty BM, Williams A (1999) The effects of sense of belonging, social support, conflict, and loneliness on depression. Nurs Res 48:215–219

Hartig T, Mitchell R, De Vries S, Frumkin H (2014) Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health 35:207–228

Hox J (2010) Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. Routledge, UK

de Jong K, Albin M, Skärbäck E, Grahn P, Wadbro J, Merlo J, Björk J (2011) Area-aggregated assessments of perceived environmental attributes may overcome single-source bias in studies of green environments and health: results from a cross-sectional survey in southern Sweden. Environ Health 10:4

Kaplan R (2001) The nature of the view from home psychological benefits. Environ Behav 33:507–542

Kawachi I, Berkman L (2000) Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I (eds) Social Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 174–190

Kuo FE, Sullivan WC, Coley RL, Brunson L (1998) Fertile ground for community: inner-city neighborhood common spaces. Am J Commun Psychol 26:823–851

Leslie E, Sugiyama T, Ierodiaconou D, Kremer P (2010) Perceived and objectively measured greenness of neighbourhoods: are they measuring the same thing? Landsc Urban Plann 95:28–33

Maas J, Van Dillen SM, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP (2009) Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 15:586–595

Mitchell R, Popham F (2008) Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. Lancet 372:1655–1660

Nieuwenhuijsen MJ Kruize H, Gidlow C et al. (2014) Positive health effects of the natural outdoor environment in typical populations in different regions in Europe (PHENOTYPE): a study programme protocol. BMJ Open 4:e004951

Pickett KE, Pearl M (2001) Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Commun Health 55:111–122

Pretty GM, Andrewes L, Collett C (1994) Exploring adolescents’ sense of community and its relationship to loneliness. J Commun Psychol 22:346–358

Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ (1999) Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol Methodol 29:1

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

Sugiyama T, Leslie E, Giles-Corti B, Owen N (2008) Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? J Epidemiol Commun Health 62:e9–e9

Triguero-Mas M, Dadvand P, Cirach M et al (2015) Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: relationships and mechanisms. Environ Int 77:35–41

Ware JE Jr (2000) SF-36 health survey update. Spine 25:3130–3139

Ware Jr JE, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A (1995) Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Medical Care AS264–AS279

Ware Jr JE, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 473–483

Weisberg S (2005) Applied linear regression vol 528. Wiley, USA

Wheaton B, Nisenbaum R, Glazier RH, Dunn JR, Chambers C (2015) The neighbourhood effects on health and well-being (NEHW) study. Health Place 31:65–74

Acknowledgements

On behalf of the PHENOTYPE Consortium, the field workers Magdalena van den Berg, Gemma Hurst, Margarita Triguero-Mas and Sandra Andrusaityte, are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Peter Spreeuwenberg (NIVEL) for his advice on the statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The work was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) [Grant Agreement No: 282,996].

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruijsbroek, A., Mohnen, S.M., Droomers, M. et al. Neighbourhood green space, social environment and mental health: an examination in four European cities. Int J Public Health 62, 657–667 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-0963-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-0963-8