Abstract

Objectives

We carried out a scoping review to identify and describe scholarly and grey literature referring to global cases of intersectoral action for health equity featuring a central role for governments.

Methods

The scoping review process systematically identified articles describing one or more cases of intersectoral action. Each article was then described in terms of the context of initiation, as well as the strategies, actors, tools and structures used to implement these initiatives.

Results

128 unique articles were found describing intersectoral action across 43 countries. A majority of the cases appear to have initiated in the last decade. A variety of approaches were used to carry out intersectoral action, but articles varied in the richness of information included to describe different aspects of these initiatives.

Conclusion

With this examination of cases across multiple countries and contexts, we can begin to clarify how intersectoral approaches to health equity have been used; however, the description of these complex, multi-actor processes in the published documents was generally superficial and sometimes entirely absent and improvements in such documentation in future publications is warranted. Richer sources of information such as interviews may facilitate a more comprehensive understanding from the perspective of multiple sectors involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing body of international evidence suggests that strengthening the determinants of health and well-being beyond the provision of health care services, such as housing, social support, income and food security, is essential to prevent or reduce inequities in health (CSD 2008; Health Council of Canada 2010; Bierman 2009, 2010). One solution is to design intersectoral approaches that involve a variety of actors including multiple government sectors, the private sector and civil society to address complex health equity problems. Such interventions have been broadly referred to as Intersectoral action for health equity (Castell-Florit Serrate 2007; Harris et al. 1995; Public Health Agency of Canada 2007; Public Health Agency of Canada, and World Health Organization 2008).

In particular, intersectoral approaches that feature a central role for governments ideally encourage governments to design and assess the effectiveness of policies with health outcomes in mind. While some of these intersectoral approaches may be systematic and durable in their approach to tackling health equity, others may be ad hoc in nature, with action initiated and implemented as new health equity problems are identified. For example, the former is exemplified by the “Health in all policies” approach (Ståhl et al. 2006; WHO and Government of South Australia 2010), which can be distinguished by policy makers and other participants integrating considerations of health, well-being and, ideally, equity “during the development, implementation and evaluation of policies and services” (WHO and Government of South Australia 2010, p. 2). Such processes may be mandated by policies, practices or long-term strategies that guide the work of government over time and across a variety of initiatives or problems.

Over the past 30 years, the concept of intersectoral action for health equity, and more recently health in all policies, is increasingly promoted by international institutions such as the World Health Organization and the European Union (Public Health Agency of Canada, World Health Organization 2008), and there is growing interest in the effectiveness, feasibility, and cost effectiveness associated with such approaches (Public Health Agency of Canada 2007). However, much of the key material is not based on academic analysis or scholarly research. For example, the World Health Organization has provided a compilation of case studies where intersectoral action was used to address health equity (Public Health Agency of Canada and World Health Organization 2008), but the scholarly literature was not systematically consulted. In another vein, a report by the National Collaborating Centre for Health Public Policy tried to articulate governmental mechanisms specifically related to cases of Health in all policies (St. Pierre 2009), but mainly focused on those settings where Health Impact Assessment (HIA) tools were used and did not address the processes related to initiation.

These and other examples point to an apparent weakness underpinning the literature aimed at informing governments and other actors about intersectoral action for health equity. There has been limited systematic research conducted to assess intersectoral approaches that have been adopted in different jurisdictions. In particular, there has been little critical reflection and empirical documentation on the processes that have led governments to use intersectoral approaches to address health equity (“initiation”), and the designs that have been used to identify and respond to problems of health equity (potential or actual) while also negotiating cross-sectoral relationships (“implementation”). A systematic examination of these processes can inform future efforts to develop and potentially customize intersectoral action for health equity, including Health in all policies approaches.

To support the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario, Canada in its work to assess the relevance of a Health in all policies approach for the province, our team at the Centre for Research on Inner City Health conducted a scoping review to identify and describe scholarly and grey literature referring to global cases of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity. A scoping review of a body of evidence is an important first step before undertaking a more intensive knowledge synthesis, particularly when the body of literature on a topic is being compiled for the first time, and/or when the phenomena under investigation are complex or non-homogeneous. The scoping process, as the name suggests, permits analysts to characterize the “extent, range, and nature” of research questions that are addressed in a body of literature (Arksey and O’Malley 2005, p. 21). This information is useful for determining what types of strategic questions are most likely to be answerable based on the body of available evidence. Therefore, a high-quality scoping review increases the efficiency and quality of future evidence syntheses and can guide the direction of future research. The purpose of this scoping review was to better understand the range and depth of evidence describing the initiation and implementation of specific cases of intersectoral action for health equity, but also to differentiate types of intersectoral action (e.g., those addressing upstream or structural health determinants) to eventually identify specific examples of interest to the Ministry.

Methods

Conceptual approach

To identify relevant domains for the scoping review, a conceptual framework was constructed as a preliminary representation of complex inputs and processes relevant to the initiation and implementation of intersectoral action for health equity. This framework was based on earlier work by Solar et al. (2009), where a typology of intersectoral action for health equity was proposed to better understand entry points for action (i.e., specific governmental interventions) on the social determinants of health and improve the practice of such pro-equity intersectoral action. The conceptual framework helps clarify the importance of contextual factors, strategies for tackling health inequities, and the multiple possible governmental and non-governmental actors involved in action. The framework also highlights other mechanisms for intersectoral action, including structures and tools for distributing power and guiding decision-making across actors, which may be key drivers of the efficaciousness of these initiatives. A detailed description of the methodology for developing the framework is described elsewhere (Shankardass et al. 2011).

The context of initiation encompasses a broad set of structural, political, cultural, historical and functional aspects of a social system that exert a powerful formative influence on patterns of social stratification, and on people’s health opportunities and potential inequities in health. For example, Kingdon’s (1984) notion of a “window of opportunity” for policy change being composed of three streams (i.e., the identification of a problem, the formulation of policy options, and the influence of political events) was a central aspect of the context of initiation. For the purposes of this scoping review, the relevance of context was indicated crudely by the setting and geographic level (e.g., local, regional, national) of intersectoral action, and an approximation of the timing of initiation.

The strategies used to tackle health equity problems by specific intersectoral initiatives were described by two typologies in our review. First, interventions may aim to reduce inequities in health by addressing “upstream”, “midstream”, or “downstream” determinants of health (equivalent to Whitehead and Dahlgren’s (2006) notion of action on structural and intermediate determinants of health and health consequences), with implications for which sectors are involved, and in what types of capacities (Box 1) (Torgersen et al. 2007). Second, health equity interventions implemented by governments can be defined by whether the approach to responding to population health differences is “universal” (i.e. a horizontal approach to equity, addressing the entire population, and providing equal treatment for equal need) or “targeted” (i.e. a vertical approach to equity, such as using means testing and provision of preferential treatment for greater needs) (Mkandawire 2005). Each approach has its strengths and limitations depending on the problems and populations of interest (Victora et al. 2004).

Government-centred intersectoral initiatives may also include a variety of non-governmental actors, such as those from academic, private, and community/civil sectors. Since intersectoral action implies collaboration between government sectors (as well as between government and non-governmental organizations), and has implications for the autonomy of participating sectors, the relationships and patterns of collaboration across governmental sectors may reflect the structure of intersectoral action, as well as the orientation and intensity of actions undertaken for health equity. Our review characterizes four distinct patterns in the relationship between sectors of government based on a typology from Solar and Irwin (2007): information sharing, cooperation, coordination and integration (Box 2). For example, greater capacity for coordination across sectors may reflect structures that highly integrate sectors and have them communicate frequently, and therefore facilitate the design of more comprehensive interventions that may be more successful in tackling health equity problems.

Intersectoral action for health equity may also rely on tools to generate systematic and predictive assessments of the effects of non-health policies, as they are being developed or after their enactment (St. Pierre 2009). The most common are variations on HIA tools, which can facilitate systematic analysis of non-health policies to determine their effect on health (e.g., Health Impact Assessment Coordinating Unit 2010). More recently, Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) tools have been designed to specifically determined effects on health equity or inequity, a more focused and narrow gaze. Variations on these tools are emerging, including such factors as inclusion of gender, sex and diversity considerations within HEIA tools to produce more nuanced analyses.

Finally, tools for monitoring and evaluating economic and health equity-related outcomes of intersectoral action are of critical importance for accountability. Although national bodies and scientific societies have established guidelines and standards for conducting economic evaluation of health care interventions (CADTH 2006; Gold et al. 1996; International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 2010), these methods might not transfer well to analyses of intersectoral action focused on health equity for various reasons. Thus, the identification of approaches to evaluate the examples of intersectoral action for health equity is crucial.

Scoping review process

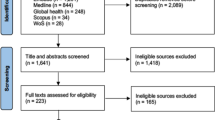

The scoping review process aimed to (1) systematically identify articles describing one or more cases of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity, and (2) describe each article as it related to how intersectoral action was initiated and implemented in a specific case (a “case article”). The review was informed by a realist methodological lens (Pawson 2006), which implies an explanatory perspective (i.e. unpacking how “x” works and under what circumstances) rather than a judgmental one (how well did “x” work?). This approach is highly suitable for synthesizing information on complex processes such as launching intersectoral action for health equity. Our process involved four stages for identifying distinct case articles (additional details describing the first four stages in this process is available in an Online Supplement). Figure 1 summarizes the flow of literature across the first four stages. Information was summarized across case articles in a fifth stage.

-

1.

Searching: Scholarly and grey literature was systematically searched for information about cases of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity including searches of several health and policy research databases using a purposely broad list of key word combinations and phrases, including (but not limited to):

-

“intersectoral-” and “policy or collaboration or action or cooperation” and “health or equity or inequity”;

-

“joined up government” and “health”;

-

“healthy public policy”;

-

Health in all policies;

-

“policy coordination” or “coordinated policy” and “health”;

-

“social determinants of health” and “policy”;

-

“health for all”;

-

“health impact assessment” and “policy”

-

-

2.

Screening: the screening stage quickly identified all articles describing potential cases of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity from the scholarly and grey literature based on the presence of three criteria described in Box 3. Six members of the research team participated in a multi-step process to review abstracts—or in the case of some grey literature and some articles where the criteria could not be examined, full documents—to identify articles containing potential cases of intersectoral action for health equity.

Box 3 Criteria for defining potential cases of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity -

3.

Sorting: literature referring to potential cases of intersectoral action for health equity was then sorted by the research team by country and sub-national region based on the extraction of information describing the specific setting and geographic level (e.g., city, province/state, country) of intersectoral action for health equity, and the case country (which was sometimes the same as the setting).

-

4.

Scoping: a table for more comprehensive extraction of information from articles about the initiation and implementation of specific initiatives was developed in consultation with the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care in Ontario based on our conceptual framework (Table 1). In some cases, there was insufficient information in the article to confirm classification, and these instances were noted for the purpose of analysis (see below).

Table 1 Information extracted from case articles during the scoping stage The scoping table was applied to specific articles to describe specific confirmed cases of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity (the aforementioned case articles) following a full review of the article. In this respect, each article may have appeared in the scoping table more than one time (e.g., if more than one confirmed case was described within). Further, a given case may have also been described by more than one article, and thus may be described in our scoping table multiple times. If a case was not confirmed, the article was not indexed in the scoping table at this stage. Four reviewers were each given a portfolio of setting specific articles to scope. Each reviewer was responsible for all articles pertaining to his or her own settings.

-

5.

Summary: a summary of scoping categories was prepared to describe how government-centred intersectoral approaches to health equity have been introduced and implemented across various settings. The proportion of case articles for which insufficient information prevented classification was also described to consider implications for more intensive knowledge synthesis based on this literature.

Results

Case articles ranged in publication from 1987 to 2010 and describing various government-centred approaches to intersectoral action for health equity across the 43 countries identified in Table 2.

Literature describing such initiatives has largely appeared over the last two decades. A majority of case articles (60%) described examples that appeared to initiate in the last decade, with 28% described examples appearing to initiate between 1990 and 1999. Eleven percent of case articles described examples starting between 1980 and 1989, and only about 5% of case articles described examples initiating prior to 1980. Case articles most often described national-level government participation (61%). Roughly two-thirds as many case articles (38%) described the involvement of state or provincial levels of government, while 31% involved local/municipal bodies. Initiatives involving supernational governments, such as the European Union, were rare (2.5%).

Results indicate that intersectoral action was often implemented with cooperation (52%) and/or coordination (42%) occurring between government sectors. Far fewer case articles described intersectoral action being facilitated through the simple one-way sharing of information (16%). Integration across sectors, where new structures and mechanisms were created to facilitate intersectoral action, was also described less often across case articles (16%). On a related note, the majority of case articles (70%) contained some description of why government sectors arrived at decisions about the initiation and/or implementation of intersectoral action. In addition to government sectors, the majority of case articles appeared to describe participation from community and/or civil sector groups (61%), and many cases articles also described participation from private sector (50%) and academic partners (42%).

Less than a quarter of case articles (22%) described government-centred intersectoral initiatives addressing upstream determinants of health, the vast majority appeared to address midstream determinants such as health behaviours or life circumstances (78%), and/or downstream determinants such as access to health care (70%). Initiatives were most often described as using both targeted and universal approaches to addressing health equity (46%), while around a quarter focused on either targeted (28%) or universal (26%) approaches.

The use of tools for the purpose of impact assessment in implementing intersectoral initiatives aimed at addressing inequities in health was described in 34% of case articles, with approximately half of these describing HIA specifically (53%), around a quarter describing HEIA (24%). Other types of impact assessment described included the use of Health Lens Analysis in South Australia (Department of Health 2010). A majority of case articles (56%) described some type of evaluation of intersectoral initiatives, although few specifically addressed any form of economic assessment (12%).

Articles varied in the richness of information contained to describe intersectoral action. In particular, while details about how or why government sectors made specific decisions about their participation in intersectoral action were commonly reported, such information was often minimal (e.g., one or two sentences) and made in passing (i.e., not a topic of focus). In general, it was not always possible for the research team to confirm classifications for specific scoping categories, and Table 3 describes the proportion of case articles for which classification could not be confirmed across scoping categories. A particularly high proportion of case articles did not contain sufficiently rich information to confirm the period of initiation of initiatives, the involvement of various non-governmental sectors, whether or not evaluations were carried out to assess the various impacts of intersectoral initiatives (particularly in terms of economic assessments), and processes of intersectoral engagement between government sectors.

Discussion

In this study, we searched scholarly and grey literature to systematically identify and describe cases of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity. Broadly, this review describes these types of initiatives having occurred across 43 countries over the last 60 years. The global distribution of these cases suggests that intersectoral approaches to health equity are feasible in a variety of social, economic and political systems. For example, among the countries identified are Canada (a liberal democracy) and Sweden (a social democratic democracy), which are both thought of as “core” to the world economy, as well as the Islamic Republic of Iran (a so-called theocracy with elements of democracy) and Sri Lanka (a socialist democracy), which are thought of as more peripheral to the world economy (Chung et al. 2010). We also described great variety in the geographic levels of action, and the strategies, actors, structures and tools used to facilitate intersectoral initiatives.

The scoping review approach was convenient in our study because we were undertaking an expedited review for the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario in order for them to assess a Health in all policies approach. It was also appropriate because there had not been any previous systematic review on this complex topic. This review sheds light on the direction and design of policies related to intersectoral action for health equity, and where and in what respects the research literature is robust or thin. Further, the classification of these examples facilitates the identification of specific types of intersectoral action for further research. For example, subsequent to this review, our team applied a definition of Health in all policies to identify 16 candidates for further investigation into this specific approach (Shankardass et al. 2011).

Intersectoral action appears to have been used most often to address downstream and midstream determinants of health, with action on upstream determinants occurring far less often. This may partly reflect the fact that, prior to the Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2008, there had been little acknowledgement or advocacy from super-national bodies that it was necessary to address structural factors to tackle health inequities (CSDH 2008; Muntaner et al. 2009; O’Campo et al. 2009). Moving forward, effort should be made to more closely investigate how, and in particular why, action on upstream determinants has been facilitated in the past, and to assess the common barriers to this type of fundamental action on inequities.

The evaluation of intersectoral action was only described in about half of case articles, and far fewer indicated the specific evaluation of economic impacts. To some extent, this may simply reflect a lack of reporting on evaluation efforts that actually occurred. Regardless, more knowledge exchange about how to appropriately measure the cross-sectoral impact of equity interventions is needed. As mentioned earlier, the application of existing guidelines and standards for conducting evaluations of economic and health outcomes of health care interventions (e.g., Gold et al. 1996; CADTH 2006) to intersectoral actions involving a diversity of sectors may be inappropriate. For example, it may be challenging for governments to carry out an economic assessment of costs and benefits related to health equity interventions that rely on environmental planning initiatives since methods used in health economics might be different than methods used in environmental economics, making comparisons challenging (Hanley et al. 2003). Moreover, equity concerns have not been incorporated into standard health economic evaluations to date (Bayoumi 2009).

The use of tools to assess the negative impacts of government policies (potential or actual) on health and/or health equity was only described in about one-third of case articles. Such impact assessment tools are particularly useful as a part of systematic approaches to decision making (e.g., the mandatory use of HIA in some settings, possibly as part of a broader Health in all policies approach) (St. Pierre 2009); therefore, they may not have been as prevalent in the current review since we included ad-hoc as well as more systematic approaches. Where impact assessment was used, HIA was the most frequently described approach, while HEIA was used less than half as often. Given that all initiatives described in our study were confirmed to have some focus on addressing health inequities, we might expect HEIA to have been used more frequently since this can facilitate a more comprehensive and nuanced assessment of potential health equity problems. Since HEIA has been developed more recently than HIA, impact assessment tools used in the past that did focus on equity may not have been described explicitly as HEIA.

Where impact assessment was not used to assess health equity problems (as above), other mechanisms for such needs assessment were noted. For example, community-integrated processes for needs assessment were used in Malaysia and Iran to address existing inequities (and prevent new ones from happening) based on a response involving government action and/or legislation (Jaafar et al. 2007; Motevalian 2007). In total, this suggests that a diversity of strategies—including but not limited to impact assessment tools—have been used by governments to identify and respond to potential or actual health equity problems.

While this scoping review was useful for identifying and broadly describing examples of intersectoral action that may be of interest to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the information extracted from articles sometimes reflects a superficial understanding of what are often complex processes. Further, while these are ostensibly multi-sectoral initiatives, most articles were written from the perspective of either one sector (e.g., often the health sector) or from an academic perspective. In this way, further work is needed to clarify how and why intersectoral approaches to health equity were used, and perspectives from multiple sectors can facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of strategies.

For example, the concept of intersectoral action as applied to government sectors suggests some need for intersectoral engagement (read: negotiation) in terms of how projects will be financed and some loss of autonomy depending on how decisions and responsibilities will be shared (if at all) (Solar et al. 2009). Although a majority of case articles contained some information about intersectoral engagement leading to either the initiation or implementation of initiatives, this information was largely descriptive and written from a single perspective, and could not be confirmed in many cases. Similarly, while the pattern of relationships described across cases (i.e., from information sharing to integration) may reflect the level of engagement and collaboration required to carry out government-centred intersectoral initiatives, those interested in using this approach would benefit from a clearer understanding of how and why intersectoral engagement facilitated the initiation and implementation of initiatives in other settings, and to what extent engagement succeeded or failed.

Questions of interest include: Was there a key policy entrepreneur that drove the initiation of these initiatives? What was the role of the health sector? What was the political context of initiation and implementation? Was there high level leadership? What were the incentives that attracted different stakeholders to participate? Were there economic incentives? And were there any missed opportunities for fostering more integrated relationships across sectors? In particular, since addressing health equity may not have been the primary motivation for collaboration for all stakeholders—for example, some may have been motivated by budgetary efficiency or health system pressures—it is important to consider such questions from the perspective of multiple stakeholders. For these reasons, empirical examples of government-centred intersectoral action for health equity need to be further investigated using intensive methods that are capable of uncovering tacit knowledge on this topic from multiple perspectives, and using multiple methods, such as interviews and case study approaches.

Conclusion

Our scoping review has identified scholarly and grey literature that begins to clarify the strategies, actors, tools and structures that have been used by governments to implement intersectoral approaches to health equity across a range of global context over the last 60 years. Yet, the description of these complex, multi-actor processes was generally superficial and sometimes entirely absent. Richer sources of information such as interviews may facilitate a more comprehensive understanding from the perspective of multiple sectors involved.

References

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework in International. J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):1–32

Bayoumi AM (2009) Equity and health services. J Public Health Policy 30:176–182

Bierman AS (ed) (2009) Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence-Based Report, Toronto, vol 1. http://www.powerstudy.ca. Accessed 15 Mar 2010

Bierman AS (ed) (2010) Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence-Based Report, vol 2. http://www.powerstudy.ca. Accessed 15 Mar 2010

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (2006) Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada. CADTH, Ottawa

Castell-Florit Serrate P (2007) Comprensión conceptual y factores que intervienen en el desarrollo de la intersectorialidad. Rev Cub Salud Pública 33(2). doi:10.1590/S0864-34662007000200009

Chung H, Muntaner C, Benach J, the EMCONET Network (2010) Employment relations and global health: a typological study of world labor markets. Int J Health Serv 40(4):229–253

Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008) Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health, Final report of the commission on social determinants of health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Department of Health (2010) The South Australian approach to Health in all policies: background and practical guide. Government of South Australia, Rundle Mall

Gold MR, Seigel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC (1996) Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford University Press, New York

Hanley N, Ryan M, Wright R (2003) Estimating the monetary value of health care: lessons from environmental economics. Health Econ 12:3–16

Harris E, Wise M, Hawe P, Finlay P, Nutbeam D (1995) Working together: intersectoral action for health. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra

Health Council of Canada (2010) Stepping it up: moving the focus from health care in Canada to a healthier Canada. Health Council of Canada, Toronto

Health Impact Assessment Coordinating Unit (2010) Thailand’s rules and procedures for the health impact assessment of public policies. National Health Commission Office, Nonthaburi

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (2010) Pharmacoeconomic guidelines around the world. ISPOR. http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/index.asp. Accessed 12 Dec 2010

Jaafar S, Suhaili MR, Mohd Noh K, Ehsan FZ, Lee FS (2007) Malaysia: Primary health care key to intersectoral action for health and equity. World Health Organization and Public Health Agency of Canada. http://www.who.int/entity/social_determinants/resources/isa_primary_care_mys.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2010

Kingdon JW (1984) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little, Brown & Co., Boston

Mkandawire T (2005) Targeting and universalism in poverty reduction. Social policy and development programme paper no. 23. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Switzerland

Motevalian S (2007) A case study on intersectoral action for health in I.R. of Iran: community based initiatives experience. World Health Organization–Public Health Agency of Canada, Tehran

Muntaner C, Sridharan S, Solar O, Benach J (2009) Against unjust global distribution of power and money: the report of the WHO commission on the social determinants of health: global inequality and the future of public health policy. J Public Health Policy 30(2):163–175

O’Campo P, Kirst M, Shankardass K, Lofters A (2009) Closing the gap in urban health inequities, round table on commission on social determinants of health report. J Public Health Policy 30(2):183–188

Pawson R (2006) Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. Sage Publications Ltd., London

Public Health Agency of Canada (2007) Crossing sectors: experiences in intersectoral action, public policy and health. Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa

Public Health Agency of Canada, World Health Organization (2008) Health equity through intersectoral action: an analysis of 18 country case studies. Minister of Health of Canada, Ottawa

Shankardass K, Solar O, Murphy K, Freiler A, Bobbili S, Bayoumi A, O’Campo P (2011) Health in all policies: results of a realist-informed scoping review of the literature. In: Getting started with health in all policies: a report to the Ontario Ministry of health and long term care. Centre for Research on Inner City Health, Toronto, Ontario. http://www.stmichaelshospital.com/knowledgeinstitute/search/details.php?id=18218&page=1. Accessed 1 Apr 2011

Solar O, Irwin A (2007) A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: discussion paper for the commission on social determinants of health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Solar O, Valentine N, Albrech D, Rice M (2009) Moving forward to Equity in Health: what kind of intersectoral action is needed? An approach to an intersectoral typology. In: 7th Global Conference For Health Promotion, Nairobi, Kenya

Ståhl T, Wismar M, Ollila E, Lahtinen E, Leppo K (eds) (2006) Health in all policies: prospects and potentials. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland

St. Pierre L (2009) Governance tools and framework for Health in all policies. National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy, International Union for Health Promotion and Education and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Quebec City

Torgersen TP, Giæver Ø, Stigen OT (2007) Developing an intersectoral national strategy to reduce social inequalities in health—the Norwegian case. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/isa_national_strategy_nor.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2010

Victora CG, Hanson K, Bryce J, Vaughan JP (2004) Achieving universal coverage with health interventions. Lancet 364(9444):1541–1548

Whitehead M, Dahlgren G (2006) Levelling up (part 1): a discussion paper on concept and principles for tackling social inequities in health. Studies on social and economic determinants of population health, No.2. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

WHO, Government of South Australia (2010) Adelaide Statement on Health in all policies, Adelaide

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Alix Freiler, Sireesha Bobbili, Dr. Lauren Bialystok, Laure Perrier, Dr. Andreas Laupacis and Dr. Irfan Dhalla for their important contributions to this work. Authors from the Centre for Research on Inner City Health gratefully acknowledge the support of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Patricia O’Campo was supported by the Alma and Baxter Ricard Chair in Inner City Health. The authors’ work was independent of the funders. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the above named organizations or of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shankardass, K., Solar, O., Murphy, K. et al. A scoping review of intersectoral action for health equity involving governments. Int J Public Health 57, 25–33 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0302-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0302-4