Abstract

Objective

A comprehensive review of cost drivers associated with alcohol abuse, heavy drinking, and alcohol dependence for high-income countries was conducted.

Method

The data from 14 identified cost studies were tabulated according to the potential direct and indirect cost drivers. The costs associated with alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, and heavy drinking were calculated.

Results

The weighted average of the total societal cost due to alcohol abuse as percent gross domestic product (GDP)—purchasing power parity (PPP)—was 1.58%. The cost due to heavy drinking and/or alcohol dependence as percent GDP (PPP) was estimated to be 0.96%.

Conclusions

On average, the alcohol-attributable indirect cost due to loss of productivity is more than the alcohol-attributable direct cost. Most of the countries seem to incur 1% or more of their GDP (PPP) as alcohol-attributable costs, which is a high toll for a single factor and an enormous burden on public health. The majority of alcohol-attributable costs incurred as a consequence of heavy drinking and/or alcohol dependence. Effective prevention and treatment measures should be implemented to reduce these costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alcohol is one of the most abused drugs all over the world, particularly in developed nations. Hazardous and harmful drinking of alcohol has been a major risk to health. A number of studies worldwide have established a causal relation between consumption of alcohol and several disease conditions leading to increased rates of morbidity and mortality (Foster and Marriott 2006; Rehm et al. 2003a, b) It has been estimated that more than 2 million deaths worldwide were attributable to alcohol consumption in the year 2002, representing 3.7% of all deaths in that year (Rehm et al. 2006b). Alcohol is one of the most important risk factors for global burden of disease (GBD), ranking fifth just behind tobacco (Ezzati et al. 2004). Moderate alcohol consumption has been related to cardiovascular beneficial effects; on the other hand, heavy drinking (HD) and alcohol dependence (AD) are implicated as a ‘potent’ contributor to the overall global burden of disease. Consequently, this has resulted in detrimental effects on health, hence significant influence on health expenditure.

In addition, occasionally drinking excess amount of alcohol can cause acute ill health in the short-term (Foster and Marriott 2006; Rehm et al. 2003a) resulting in accidents and injuries. Drinking alcohol is also responsible for a number of crimes, including drunk driving, violence, and sexual assaults. Countries, therefore, incur expenditures for law enforcement, other welfare system services, and material damages associated with alcohol use and abuse. Also, there are indirect costs on account of the productivity losses due alcohol-related mortality, morbidity, and other impairment.

Many consequences of alcohol drinking necessitate societal intervention involving expenses that can be accounted for; therefore, the quantification of social costs to society has been used to determine social consequences of alcohol use (Rehm 2001). These social costs presented as a single monetary amount provides a useful indicator of alcohol abuse and relevant information for alcohol policy formulation (Godfrey 1997). To date, several studies have been conducted to evaluate the cost of alcohol use and abuse. Cost studies for several countries have been regularly updated to address the change in the pattern of alcohol abuse and determine the impact of training and prevention programmes as well as new laws governing alcohol consumption. However, there is variation between methods used for these cost studies by different authors and for different countries. Cost drivers in all these studies vary, sometimes to a large extent. Again, while most of the studies have identified costs associated with alcohol consumption as a whole, there have been few attempts to make out what portion of that cost is associated with heavy drinking and alcohol dependence as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version IV (DSM-IV) or the International Classification of Diseases, version 10 (ICD-10).

In the present paper, representative alcohol cost studies from a number of high income countries have been selected and compared for the cost drivers used to determine the alcohol-attributable cost in order to formulate a general template for cost drivers and to identify the gaps in the cost studies in relation to the determination of cost drivers. An attempt has also been made to find out the impact of HD/AD on total alcohol-attributable social costs.

Method

Literature search

A literature search on alcohol-attributable social cost studies was performed in multiple electronic bibliographic databases from January 1992 to June 2009, including: Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsychINFO, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews using the combination of the key words: alcohol, cost, dependence, abuse, use, disorder, heavy drinking, and productivity losses. The search was not limited geographically or to English language publications. In addition, we conducted manual reviews of the citations in the relevant articles.

The contents of identified 110 abstracts were reviewed independently by three investigators to determine whether they contained data on cost drivers associated with alcohol consumption. We selected a few high-income countries from Europe, Australia, and Asia in addition to G8 countries for comparison. For many countries of interest, only one study was available. When there was more than one study for any country, the most recent study was more comprehensive than the previous studies in all cases. Figure 1 presents a flow diagram describing selection of alcohol cost studies for the analysis.

Data extraction

Information on alcohol-related costs from the identified studies was independently extracted by three investigators. In order to calculate inter-rater reliability (IRR), Fleiss’ κ statistics using attribute agreement analytic method was used. All analyses related to IRR were computed using Minitab statistical software. There was a very high IRR (κ = 0.81, P < 0.0001) among three reviewers (SM, JP, LP) across all variables coded. Discrepancies, if any, were reconciled by a fourth investigator (JR) independent of the first process. Different cost drivers as suggested by the International Guidelines for Estimating the Costs of Substance Abuse (Single et al. 2003) were obtained. For all the countries, both direct (healthcare costs, legal enforcement costs, and other direct costs; see Table 2) and indirect costs (due to productivity losses) were taken.

Derivation of costs for comparison

All of the countries used the local currency for estimating costs. Most of the countries used the currency year of the costing year, although a few countries used a different currency year. As France, Italy and Spain adopted the Euro in 2001, their respective costs estimated in the then local currency were converted to Euro values using the final currency conversion value when the Euro was adopted (Euro Working Group 1999). Subsequently, the estimated costs in individual studies were converted to 2006 currency values using currency inflation rates obtained from consumer price indices (US Department of Labor 2007) except for New Zealand, for which the data from Reserve Bank of New Zealand (2006) was used. Ultimately, these values were converted to 2006 US Dollar (United Nations 2007). GDP (PPP) values of different countries for the year 2006 were obtained from the CIA World Fact Book (CIA 2007). GDP (PPP) values of England and Wales and Scotland were derived from the GDP (PPP) value of UK by dividing it in proportion of their respective population in 2001 (88.5% of total UK population for England and Wales and 8.6% of total UK population for Scotland). Finally, the population weighted averages of all cost components, total cost, and cost as percent GDP (PPP) were calculated for comparison.

Definition of alcohol abuse, heavy drinking/alcohol dependence

Our study defined alcohol abuse as any alcohol use that involves a net social cost additional to the resource costs of the provision of that substance (Collins and Lapsley 1991). Heavy drinking was defined as a daily consumption of ≥60 g of pure alcohol for men (at least five standard drinks of pure alcohol) and ≥40 g of pure alcohol for women (at least 3–4 standard drinks) (English et al. 1995). Alcohol dependence was operationalized as the explicit mention of costs for this ICD-10 category; in addition, all disease categories with “alcoholic” in its name or which had alcohol-attributable fractions (AAF) of 100% were counted as due to HD/AD.

Derivation of costs of heavy drinking and alcohol dependence

Most cost studies included only information on the costs of alcohol abuse and did not show any details of costs for HD/AD. Therefore, we estimated the costs of HD/AD indirectly for all the countries except for Germany, where disease-specific details were available.

All alcohol-dependence categories (e.g., alcoholic cardiomyopathy or alcoholic gastritis) were set to 100% AAFs by definition. The formula for the proportion (fraction) of a disease attributable to heavy drinking (AAFHD) was derived from the basic formula for AAF (Patra et al. 2009). Then AAFHD was directly calculated from alcohol exposure prevalence proportions in Canada and the disease- and sex-specific risks pooled relative risks (RRs) from meta-analysis (Rehm et al. 2006b). Using above methodology, we separated the (acute care) hospital days due to HD/AD from the net alcohol-attributable hospital days by broad disease categories. The following fractions attributable to heavy drinking/alcohol dependence were found: malignant neoplasms 29.9%; diabetes 17.3%; neuropsychiatric conditions 86.8%; cardiovascular diseases 45.8%; digestive diseases 61.3%; skin diseases 16.1%; maternal conditions 42.8%; other disease conditions viz skin diseases, toxicity, etc. 50%.

Overall, a fraction of 60.7% attributable to HD/AD from the net total alcohol-attributable hospital days was derived. These proportions were calculated in a way that the alcohol-related conditions with an attributable fraction of 100% were included in the broad disease categories. The fractions attributable to HD/AD for different kinds of injuries (43.7%) were directly taken from Patra et al. (2009). Since all non-Canadian studies, with the exception of Germany, did not provide disease-specific costs, we applied the overall proportion (60.7%) of Canada to their individual cost parameters to derive total costs due to HD/AD. In the study from Germany, costs were given by broad disease categories, and it was possible to calculate its overall proportion (58.5%) of HD/AD using Canadian disease-specific proportions.

Results

Overall costs of alcohol use and abuse

Table 1 presents the social cost estimates for different countries. USA seems to have incurred the highest direct healthcare cost. Healthcare cost as percent total alcohol-attributable cost ranged from 2.8% (New Zealand) to 29% (Germany). As percent GDP (PPP), Germany incurred the highest (0.36) and Australia had the lowest (0.03) value. There were a few differences, however, among countries on the description of healthcare costs. The study from the USA estimated all healthcare costs as medical consequences. It was, therefore, not possible to segregate the cost to hospitalization, non-hospitalization, and prescription drug categories. In addition to the USA study, studies from Germany, Italy, Japan, and Spain also did not estimate any cost for prescription drugs/medication. In relation to the population-weighted average, Canada, Denmark, Germany, and Japan incurred more costs for alcohol-attributable healthcare than the average as percent GDP (PPP).

UK (England and Wales) led all the countries in the cost toward law enforcement as percent total alcohol-attributable cost. As percent GDP (PPP), UK (England and Wales) also incurred the highest cost (0.71) toward law-enforcement, and France incurred a negligible cost (0.01). The study from Germany did not report any cost toward law enforcement. Not all the countries have recorded entire law enforcement costs for police, courts, incarceration, etc. resulting in a broad range of these costs between different countries.

Australia, France, and Italy incurred more than a quarter of their total alcohol-attributable costs in terms of other direct social cost that included research, prevention and training, administrative costs, and material damages, etc. Cost of material damage due to fire and accidents was the major other direct social costs in the case of Australia, Canada, Italy, Spain, USA, and Switzerland (see Table 2). While insurance expenditure due to road accidents was the most predominant in the case of France and New Zealand, cost of social work services was the major cost component for Denmark, Japan, Scotland, and Sweden. In the cost study for Germany, other direct social costs have been shown as non-medical costs. In the case of the UK (England and Wales), no other direct social cost was reported besides healthcare costs and law-enforcement costs.

Indirect costs are segregated into two components: productivity loss due to premature mortality and productivity loss due to morbidity and other productivity losses (due to absenteeism, reduced activity, early retirement, and temporary inability). While cost due to morbidity has been higher than the cost due to mortality in the case of Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Sweden, UK (England and Wales), and the USA, it has been otherwise with the rest, namely, France, Germany, Scotland, and Switzerland. The study from Spain has not included any productivity loss due to mortality, although loss due to morbidity has been estimated. In relation to the population weighted average, only the USA seems to have more than average costs for alcohol-attributable productivity losses.

The total cost of alcohol abuse for each country was estimated as percentage of 2006 GDP (PPP) of the respective countries. While Australia, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland are found to spend less than 1% of their respective GDP (PPP), all other countries are found to spend more than 1% of their respective GDP (PPP).

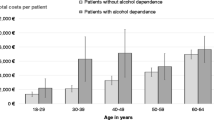

Cost of heavy drinking and alcohol dependence

Table 3 gives an overview of the social costs attributable to heavy drinking/alcohol based on the same studies as the social costs of alcohol abuse above. Again, not only the absolute costs were estimated but also their proportion of the 2006 GDP (PPP) of the respective countries. For the three countries, namely, New Zealand, UK (England and Wales), and USA, HD/AD cost as percent GDP (PPP) was more than the weighted average of 0.96%.

Discussion

There are some limitations related to several methodological issues of this comparative study. The main problem with the social cost of substance abuse studies is the use of eclectic and differing methodologies by studies resulting in varying cost estimates. Despite these differences, the overall costs in different studies are surprisingly similar in terms of their proportion of GDP (PPP), which is also a reflection that these countries are fairly similar in terms of wealth and per capita alcohol consumption (Rehm et al. 2004). Another limitation specifically for the estimates of costs attributable for heavy drinking or alcohol dependence was the transfer of Canadian data to other countries. On the other hand, all the countries examined are similar in that they are established market economies with a high level of consumption compared to the global average.

The indirect costs amount to nearly 50% or more of the total costs for all countries except Australia and Denmark. On average, indirect cost due to alcohol abuse is more than the direct cost due to alcohol abuse (Fig. 2). However, it may be noted that the data on income, employment, and alcohol consumption are used to measure productivity losses, as direct measures of productivity are not available (Sindelar 1998) leading to variation of the cost due to productivity losses in different studies.

Although law enforcement costs and other direct social costs are substantial, healthcare costs seem to be the most predominant category in terms of direct alcohol-attributable costs. It is, however, possible that the actual healthcare costs might even have been higher than estimated as some studies have left out a few cost determinants, such as prescription drugs, cost of laboratory tests or rehabilitation, etc. Most of the countries seem to incur 1% or more of their GDP (PPP) as alcohol-attributable cost. Population-weighted average for alcohol-attributable cost as percentage of GDP (PPP) is calculated to be 1.58%. The variation in cost could be attributed to difference in the economic approach and the number of variables used for cost estimation. Quite possible, some cost determinants have been left out. Nevertheless, this value (1.58%), to a great extent, corroborates with the values obtained by Anderson and Baumberg (2006) who determined an average of 1.3% of GDP as alcohol-related cost for European countries. This is obviously worrisome for a single cost factor, such as, alcohol abuse.

The economic cost of alcohol abuse is substantial in major market economies. HD and AD make up a considerable portion of these costs. The various health problems associated with HD/AD are not only detrimental to the victim himself but there is also the pain and suffering of the all individuals, besides the victim affected. In addition to morbidity and mortality, alcohol is also associated with increase in accidents and accident severity, unemployment, homelessness, criminality, domestic violence, and child abuse, etc. The strong influence of alcohol consumption on society and the resulting cost burden necessitates sincere and concerted efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption. Countries should formulate policies to prevent and reduce problems of disorder and violence at societal level including measures designed to improve the management of drinking environments, and to change patterns of drinking so that the number of episodes of heavy drinking and intoxication can be reduced.

Alcohol cost studies are useful in identifying what aspects of alcohol abuse involve the greatest economic costs, what specific problems occur due to alcohol abuse and dependence in particular geographic regions. This information can help appropriately target interventions. Despite being helpful in estimating economic burden of alcohol drinking and guiding formulation of public health policies in different countries, discrepancies remain regarding methodologies, range of cost drivers selected for the study, and assumptions made therein. While some alcohol cost studies are prevalence-based, some others are incidence-based. There are different approaches, such as, human capital approach, the friction cost approach, and hybrid approach for determining productivity loss. Future cost studies should harmonize methods through guidelines or by using a standard reference case analysis. Whenever possible, a societal perspective should be adopted in order to include all relevant costs. However, the selected model needs to consider a country-specific socio-economic environment. As labor markets are not at full employment in most cases, hybrid approach should be appropriate.

There is lack of uniformity in the range of cost drivers too. A majority of the studies do not include all direct and indirect cost drivers for estimation of the cost of alcoholism. While some do not consider the legal costs or other direct social costs, some studies do not include all indirect costs due to absenteeism, reduced activity due to short- and long-term disability or premature mortality.

All alcohol economic evaluations that adopt a societal perspective should include all relevant direct (medical costs, legal costs and other direct social costs such as research, training, and prevention programs) and indirect costs (due to absenteeism, reduced activity due to short- and long-term disability or premature mortality). Exclusions should be explicitly justified. Prospective authors may follow the International guidelines for estimating the costs of substance abuse (Single et al. 2003). Rehm et al. (2006a, 2007) and Gnam et al. (2006) provide suggested templates for cost calculation.

There are limited attempts to disaggregate the alcohol-attributable costs according to different drinking patterns, including separating out the cost of alcohol dependence. There are also a few studies examining what portion of this economic cost is avoidable (Rehm et al. 2007) or what changes have occurred due to policy interventions (Chisholm et al. 2006). It is desirable that future studies address these aspects.

Finally, a huge portion of the costs of alcohol are avoidable (Rehm et al. 2007). There are effective and even cost-effective interventions as well as treatment available to reduce these costs (Babor et al. 2003; Room et al. 2005). Given this situation, we see no justification in continuing the status quo.

References

Anderson P, Baumberg B (2006) Alcohol in Europe: a public health perspective. A report for the European Commission. Institute of Alcohol Studies, UK

Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S et al (2003) Alcohol: no ordinary commodity. Research and public policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cabinet Office (2003) Alcohol misuse: how much does it cost? Cabinet Office Strategy Unit, London

Chisholm D, Doran C, Shibuya K, Rehm J (2006) Comparative cost-effectiveness of policy instruments for reducing the global burden of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev 25(6):553–565

CIA (2007) The world fact book. Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC

Collicelli C (1996) Income from alcohol and the costs of alcoholism: an Italian experience. Alcologia 8:135–143

Collins DJ, Lapsley H (1991) Estimating the economic costs of drug abuse in Australia. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra

Collins DJ, Lapsley H (2002) Counting the cost: estimates of the social costs of drug abuse in Australia in 1998–9. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra

Devlin NJ, Scuffman PA, Bunt LJ (1997) The social cost of alcohol abuse in New Zealand. Addiction 92:1491–1505

English DR, Holman CDJ, Milne E, Winter MJ, Hulse GK, Codde G (1995) The quantification of drug caused morbidity and mortality in Australia 1995. Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health, Canberra

Euro Working Group (1999) Migrating to Euro: System strategies and best practices recommendations for the adaptation of information systems to the Euro. Euro Working Group

Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL (2004) Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. World Health Organization, Geneva

Fenoglio P, Parel V, Kopp P (2003) The social cost of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs in France, 1997. Eur Addict Res 9:18–28

Foster RK, Marriott HE (2006) Alcohol consumption in the new milennium—weighing up the risks and benefits for our health. Nutr Bull 31:286–331

García-Sempere A, Portella E (2002) Los estudios de coste del alcoholismo: marco conceptual, limitatciones y resultados en Espana. Adiccone 14:141–153

Gnam W, Sarnocinska-Hart A, Mustard C, Rush B, Lin E (2006) The economic costs of mental disorders and alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug abuse in Ontario 2000: cost of illness study

Godfrey C (1997) Lost productivity and costs to society. Addiction 92(Suppl 1):S49–S54

Hardt F, Grønbæk M, Tønnesen H, Kampmann P (1999) De samfundsøkonomiske konsekvenser af alkoholforbrug. Sundhedsministeriets, Sundhedsanalyser Report No. 10, ISBN 87-17-06959-9

Jeanrenaud C, Priez F, Pellegrini S, Chevrou-Severac H, Vitale S (2003) Le coût social de l’abus d’alcool en Suisse (The social costs of alcohol in Switzerland). Institut de recherches économiques et régionales, Université de Neuchâtel

Johansson P, Jarl J, Eriksson A et al (2006) The social costs of alcohol in Sweden 2002. SoRAD Forskningsrapport nr. 36

Konnopka A, König H (2007) Direct and indirect costs attributable to alcohol consumption in Germany. Pharmacoeconomics 25:606–618

Nakamura K, Tanaka A, Takano T (1993) The social cost of alcohol abuse in Japan. J Stud Alcohol 54:618–625

Patra J, Taylor B, Rehm J (2009) Harms associated with high-volume drinking of alcohol among adults in Canada in 2002: a need for primary care intervention? Contemp Drug Probl (in press)

Rehm J (2001) Concepts, dimensions and means of alcohol-related social consequences—a basic framework for alcohol-related benefits and harm. In: Klingemann H, Gmel G (eds) Mapping the social consequences of alcohol consumption. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Rehm J, Room R, Graham K, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Sempos CT (2003a) The relationship of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking to burden of disease: an overview. Addiction 98:1209–1228

Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M et al (2003b) Alcohol as a risk factor for global burden of disease. Eur Addict Res 9:157–164

Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M et al (2004) Alcohol use. In: Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, Murray CJL (eds) Comparative quantification of health risks. global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. World Health Organization, Geneva, pp 959–1108

Rehm J, Baliunas D, Brochu S et al (2006a) The costs of substance abuse in Canada 2002. Canada Centre for Substance Abuse, Ottawa

Rehm J, Patra J, Baliunas D, Popova S, Roerecke M, Taylor B (2006b) Alcohol consumption and the global burden of disease 2002. Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Management of Substance Abuse, World Health Organization, Geneva

Rehm J, Gnam W, Popova S et al (2007) The costs of alcohol, illegal drugs, and tobacco in Canada, 2002. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 68(6):886–895

Room R, Babor T, Rehm J (2005) Alcohol and public health: a review. Lancet 365:519–530

Sindelar J (1998) Social costs of alcohol. J Drug Issues 28(3):763–780

Single E, Collins D, Easton B et al (2003) International guidelines for estimating the costs of substance abuse, 2nd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva

United Nations (2007) The United Nations operational rates of exchange. United Nations Treasury, United Nations

US Department of Health and Human Services (2000) Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: estimates, update methods, and data. US Department of Health and Human Services

US Department of Labor (2007) Consumer price indexes, sixteen countries, 1950-2006. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Office of Productivity and Technology

Varney SJ, Guest JF (2002) The annual societal cost of alcohol misuse in Scotland. Pharmacoeconomics 20(13):891–907

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial assistance for this study from Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Computing proportion of disease attributable to heavy drinking/alcohol dependence as part of all alcohol-attributable disease

The formula for the proportion (fraction) of a disease attributable to heavy drinking (AAFHD) was derived from the basic formula for AAF. Then AAFHD was directly calculated from alcohol exposure prevalence proportions in Canada and the disease- and sex-specific risks pooled relative risks (RRs) from meta-analyses (see Rehm et al. 2006) from the below formula. All alcohol-dependence categories (e.g., alcoholic cardiomyopathy or alcoholic gastritis) were set to 100% AAFs by definition.

where i exposure category with baseline exposure or no alcohol i = 0; P i prevalence of the ith category of exposure; RR i relative risk at exposure level i compared to no consumption.

Using above methodology, we separated the (acute care) hospital days due to HD/AD from the net alcohol-attributable hospital days by broad disease categories. The following fractions attributable to heavy drinking/alcohol dependence were found:

-

malignant neoplasms: 29.9%;

-

diabetes: 17.3%;

-

neuropsychiatric conditions: 86.8%;

-

cardiovascular diseases: 45.8%;

-

digestive diseases: 61.3%;

-

skin diseases: 16.1%;

-

maternal conditions: 42.8%;

-

other disease conditions—toxicity etc.: 50%.

Overall, a fraction of 60.7% attributable to HD/AD from the net total alcohol-attributable hospital days could be derived. As indicated above, these proportions were calculated in a way that the alcohol-related conditions with an attributable fraction of 100% were included in the broad disease categories. The fractions attributable to HD/AD for different kinds of injuries (43.7%) were directly taken from Patra et al. (2009). Since all non-Canadian studies, with the exception of Germany, did not provide disease-specific costs, we applied the overall proportion (60.7%) of Canada to their individual cost parameters to derive total costs due to HD/AD. In Germany, costs were given by broad disease categories, and it was possible to calculate its overall proportion (58.5%) of HD/AD using Canadian disease specific proportions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohapatra, S., Patra, J., Popova, S. et al. Social cost of heavy drinking and alcohol dependence in high-income countries. Int J Public Health 55, 149–157 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0108-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0108-9