Abstract

Historically, it has been assumed that oxidative stress contributes to tumor initiation and progression solely by inducing genomic instability. Recent studies indicate that reactive oxygen species are upregulated in tumors and can lead to aberrant induction of signaling networks that cause tumorigenesis and metastasis. Here we review the role of redox-dependent signaling pathways and transcription factors that regulate tumorigenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Oxidative stress is a hallmark of many tumors and is caused by an imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the cell’s ability to clear oxidants. Uncontrolled increases in ROS can lead to direct damage of proteins, lipids, and DNA [1]. However, studies show that lower levels of ROS can activate intracellular signaling pathways [2] that lead to cellular proliferation and gene transcription [3]. ROS can potentially be carcinogenic and promote tumor progression [4]. Historically, it has been assumed that oxidative stress contributes to tumor initiation and progression by causing genomic instability [5]. However, in the past two decades studies have suggested that, in addition to causing genomic instability, ROS can also increase tumorigenesis by activating signaling pathways that regulate cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis [6] (Fig. 1). Here we focus on ROS regulation of signaling pathways and transcription factors for tumor initiation and progression.

Sources of reactive oxygen species

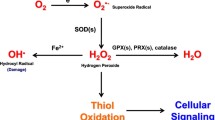

ROS are generated when oxygen is reduced resulting in the production of reactive species, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (·OH), and superoxide (·O2). Superoxide can be generated both enzymatically and nonenzymatically. Superoxide dismutases (SOD1, SOD2, SOD3) convert superoxide to hydrogen peroxide. Glutathione peroxidase or catalase can convert hydrogen peroxide to water. Hydrogen peroxide and superoxide are implicated in the activation of signaling pathways [1–3]. By contrast, hydrogen peroxide can react with iron to generate hydroxyl radicals that cause DNA damage [7, 8].

NADPH oxidase is one of the best described enzymatic sources of superoxide [9, 10]. NADPH oxidase catalyzes the production of superoxide from oxygen and NADPH. NADPH oxidase was first found to be present in phagocytes [11]. Recent studies indicate that NADPH oxidase family members are found in a wide array of tissues [10] and include the Nox family members NOX1–5, and DUOX1–2. Five Nox isoforms (Nox1–5) form the basis of distinct NADPH oxidases [10]. The prototypic NADPH oxidase is composed of two membrane-bound components consisting of a catalytic Nox2 subunit (also known as gp91phox) and a p22phox subunit. The activation of this catalytic core relies on association with several cytosolic proteins, p67PHOX, p47PHOX, p40PHOX, and rac 1 or 2 [12]. Activation of the oxidase occurs when the cytosolic components migrate to the cell membrane so that the complete oxidase can assemble [10]. The notable exception is Nox4, which does not require p47PHOX, p67PHOX, or Rac for activation [13, 14]. Fibroblasts overexpressing Nox1 displayed increased levels of superoxide and exhibited a transformed phenotype in xenograft models [15]. Nox1 signals angiogenic and tumorigenic effects through hydrogen peroxide [16]. Classically, NADPH oxidases have been thought to generate superoxide at the plasma membrane and release it into the extracellular space where it is converted into hydrogen peroxide. Subsequently, the extracellular hydrogen peroxide can traverse back through plasma membranes into the cytosol. Recent evidence suggests that NADPH oxidase-generated superoxide can also occur in endosomes and endoplasmic reticulum [17, 18]. The superoxide generated in these intracellular compartments can be converted into hydrogen peroxide, which traverses the membranes of these intracellular compartments into the cytosol. NADPH oxidase signaling localized to the plasma membrane, such as the PI3 kinase pathway, likely regulates signaling associated with plasma membrane [19]. By contrast, NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide generation in intracellular compartments regulates NF-κB-dependent transcription [17].

The electron transport chain in the mitochondria is the major site of non-enzymatic superoxide formation. The mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) is made up of four multi-protein complexes (I–IV) embedded in the inner membrane. Complex I and II oxidize NADH and FADH2 and transfer the resulting electrons to ubiquinol, which carries electrons to complex III. Complex III shunts the electrons across the intermembrane space to cytochrome c, which brings electrons to complex IV. Complex IV then uses the electrons to reduce oxygen to water. Complexes I, II, and III generate superoxide as a result of electron flux through these complexes [20]. Complexes I and II generate ROS within the mitochondrial matrix while complex III generates superoxide and releases it into either the intermembrane space or the matrix [21–26]. Superoxide generated in the intermembrane space can escape into the cytoplasm through voltage-dependent anion channels [27], and these ROS can initiate intracellular signaling [28].

Oncogenes induce ROS

Many cancer cells show increased levels of ROS [29]. NIH 3T3 fibroblasts stably transformed with a constitutively active H-RasV12 produced large amounts of the ROS superoxide through Rac, a member of the Ras superfamily [30]. The mitogenic activity of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts expressing H-RasV12 was inhibited by treatment with the chemical antioxidant N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) indicating that Ras can stimulate mitogenic signaling through production of ROS. Additionally, oncogenic K-Ras generation of hydrogen peroxide contributes to the tumorigenicity [31]. Rac can also induce ROS resulting in cell spreading and migration [32]. Collectively, these studies provide evidence that the Ras oncogene can regulate cell proliferation and cell migration.

Deregulated expression of Myc also increases production of ROS. Normal human fibroblasts expressing Myc have increased levels of ROS [33]. The increase in ROS levels in these cells correlated with an induction of DNA damage without activation of apoptosis [33]. These data suggest that Myc can deregulate the cell’s DNA damage response leading to tumor progression through genetic instability. Mitochondrial-targeted vitamin E analog (a potent antioxidant) protected cells from Myc-elicited oxidative DNA damage [34]. These results suggest that Myc-induced cellular transformation is dependent on mitochondrial ROS. By contrast, c-Myc overexpression in NIH3T3 MEFs leads to ROS accumulation, which activates apoptosis [35]. Recent studies indicate that there is a specific “threshold” level of Myc expression that correlates with Myc’s biological activities [36, 37]. Low levels of deregulated Myc are conducive to cell proliferation and oncogenesis, while high levels of Myc overexpression correspond to activation of apoptosis [36]. We speculate that the level of ROS induced by c-Myc could be responsible for Myc’s biological output. High Myc expression induces high levels of ROS leading to DNA damage or apoptosis, while lower Myc expression induces lower levels of ROS resulting in cellular proliferation and tumor growth.

ROS activate signaling pathways

Low or transient levels of ROS can activate cellular proliferation or survival signaling pathways, while high levels of ROS can initiate damage or cell death. ROS can activate kinases and/or inhibit phosphatases resulting in stimulation of signaling pathways [38, 39]. ROS can also regulate proteinases and matrix metalloproteins [40]. Many phospho-proteins and proteinases contain cysteine residues which, upon oxidation, result in formation of disulfide bonds leading to activation of signal transduction pathways [41, 42]. This reaction is reversible since the disulfide reductases thioredoxin (Trx) or glutaredoxin (Grx) catalyze the reversible reduction of disulfides to a dithiol within the target protein. Trx and Grx contain a common dithiol/disulfide active site motif (Cys-X-X-Cys) [43]. The reduction of disulfide results in the oxidation of Trx forming a disulfide within the Trx, which is then reduced by thioredoxin reductase using electrons from NADPH. An example of this redox-based signaling is the activation of the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1). ASK1 is bound to a reduced Trx in its inactive form. ROS oxidize Trx causing disassociation from ASK1 to initiate activation through auto-phosphorylation of ASK1 [44]. ROS also are regulators of signaling pathways such as the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) MAPK pathway, which is important for cell proliferation [45, 46], and the PI3K/Akt pathway, which is important for cell growth and survival [47, 48] and transcription factors such as hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) [28]. In the next sections we focus on the role ROS play in the regulation of ERK, PI3K, and HIFs (Fig. 2).

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

ERK1/2 are mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) that are important in cell proliferation, differentiation, invasion, and apoptosis [49–52]. Dysregulation of the MAPK pathway can lead to uncontrolled cellular proliferation or permanent cell cycle arrest [53]. The Ras oncogene can activate the ERK MAPK pathway. Ras activates Raf, which stimulates MEK1/2, followed by activation of ERK1/2 MAPK to promote cell proliferation through the induction of cyclin D1. Multiple studies indicate that activated Ras induces an accumulation of cyclin D1 [54–56]. Ras activation of ERK1/2 is necessary and sufficient for transcriptional induction of the cyclin D1 gene [57, 58]. ERK1/2-sustained activation of cyclin D1 expression is required throughout G1 in order to proceed to the S phase [59, 60]. Conversely, high levels of ERK1/2 activation over long periods of time can lead to cell cycle arrest [61–63]. Thus, the duration and the intensity of the ERK1/2 signal determine the outcome of the cellular response.

There is integration between the levels of ROS in a cell and the levels of MAPK signaling that are necessary for cell cycle arrest or progression. MEFs deficient in manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) have increased levels of superoxide corresponding to a sustained expression of cyclin D1 and an inability to exit the proliferative phase of the cell cycle [64]. In contrast, MEFs that over-expressed MnSOD underwent quiescence and did not display elevated levels of superoxide or cyclin D1 expression [64]. Additionally, ROS can inactivate phosphatases responsible for dephosphorylating ERK1/2, resulting in sustained ERK1/2 activation [65]. The best-characterized example of ROS-mediated inactivation of a phosphatase is PTP1B, which is inhibited by the reversible ROS-mediated oxidation of an active site cysteine residue [66]. ROS levels increase throughout the cell cycle, and ablation of ROS using the antioxidant Tempol leads to late G1 cell cycle arrest [67]. Although, there is substantial evidence that ROS regulate ERK activation, the direct targets of ROS responsible for ERK activation still need to be elucidated.

Phosphoinositide 3 kinase signaling pathway

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway is required for a number of cellular processes including cell growth, survival, proliferation, and motility [68]. Upon pathway activation, growth factor receptors activate the catalytic subunit, p110, of PI3K through recruitment of the regulatory subunit, p85, or through direct Ras activation of p110. p110 then phosphorylates phosphoinositides (PI) to generate PI (3,4,5) P3 (PIP3). Binding of PIP3 to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of Akt allows for translocation of Akt to the plasma membrane, where Akt is phosphorylated and activated by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) and mTORC2 [69, 70]. Akt is negatively regulated by the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten), a phospholipid phosphatase that inhibits the activity of PI3K by dephosphorylating PIP3 [71]. Overexpression of Akt is associated with resistance to apoptosis, increased cell growth, and cellular proliferation [72]. Mammalian cells express three Akt genes, Akt1, Akt2, and Akt 3. Furthermore, inactivating mutations or deletions of PTEN lead to uncontrolled Akt activity and are frequently seen in human malignancies [71]. Amplification and overexpression of the gene encoding p110 is also observed in many human cancers [73]. Additionally, oncogenic Ras mutations can activate Akt in epithelial tumors [74].

The PI3K pathway can be affected by the redox state of the cell [48, 75]. Exogenous hydrogen peroxide treatment of cells results in activation of Akt [76]. The best known direct target of oxidants in the PI3K/Akt pathway is PTEN. ROS can oxidize cysteine residues of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) resulting in their inactivation [38]. PTEN is inactivated by hydrogen peroxide through the formation of a disulfide between the active site cysteine (Cys124) and a vicinal cysteine (Cys71) [77, 78]. Mitochondrial-generated ROS can also inhibit PTEN resulting in endothelial cell sprouting in a three-dimensional in vitro angiogenesis assay [79]. Other phosphatases such as protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) are also redox sensitive and can regulate the PI3K/Akt pathway [80]. PP2A can dephosphorylate Akt on both threonine 308 and serine 493, thereby inactivating Akt activity [81]. The consequence of inhibiting these important phosphatases is a dysregulation of Akt signaling leading to uncontrolled cellular proliferation, enhanced survival, and growth.

ROS activate hypoxia inducible factors

Hypoxia activates a family of transcription factors called hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs). HIFs are a heterodimer consisting of a constitutively stable subunit, HIFβ, and an oxygen sensitive subunit, HIFα [82]. There are three HIFα isoforms, HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α. Under normal oxygen conditions (21% O2), HIFα is hydroxylated at proline residues by prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) [83, 84]. Hydroxylated proline residues of HIFα protein are recognized by the E3 ubiquitin ligase von Hippel-Landau protein (pVHL), which targets HIFα to the proteosome [85–87]. Oxygen tension also regulates the interaction of HIF-1α with the transcriptional co-activators p300 and CBP. Asparagine hydroxylation of residue 803 of HIF-1α by the enzyme FIH-1 (factor inhibiting HIF-1) blocks the binding of p300 and CBP to HIF-1α, thus inhibiting HIF-1-mediated gene transcription [88–90]. Under hypoxia, HIFα is not hydroxylated by PHDs and FIH, which prevents pVHL targeting to the proteosome, allowing HIFα to translocate to the nucleus and dimerize with HIFβ. Moreover, p300 and CBP can then be recruited to the HIF complex allowing transcriptional activation of HIF target genes. HIF-1α and HIF-2α have been implicated in regulating tumorigenesis by controlling genes involved in metabolism, angiogenesis, and metastasis [91–93].

Hypoxia increases mitochondrial ROS to stabilize HIFα [94]. Early studies demonstrated that cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA by treatment with ethidium bromide (ρ cells) failed to increase ROS and stabilize HIF-1α during hypoxia [95]. ρ Cells are respiratory incompetent and do not generate ROS [96]. Antioxidants also prevented hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α [97]. ETC inhibitors such as rotenone, myxothiazol, and stigmatellin can block hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α [95, 97, 98]. Additionally, cells depleted of cytochrome c or the Rieske–Fe–S protein (RISP), a complex III subunit, fail to increase ROS production during hypoxia and do not stabilize HIF-1α protein under hypoxic conditions [99–101].

Recently, we demonstrated that complex III is the site of ROS generation during hypoxia responsible for stabilizing HIF-1α protein [102]. Complex III is made up of 11 subunits, 3 of which are responsible for electron transport (Rieske–Fe–S protein, cytochrome b, and cytochrome c 1). Two electrons travel from ubiquinol to cytochrome c through the ubiquinone (Q) cycle within complex III [103]. One electron from ubiquinol is transferred to the Rieske–Fe–S/cytochrome c 1 subunits, resulting in the transient formation of the radical ubisemiquinone, which ultimately passes the second electron to cytochrome b. Ubisemiquinone can pass an electron to oxygen to produce superoxide at the Qo site of complex III. Thus, cells depleted of RISP cannot initiate the Q-cycle and generate ROS, while cells depleted of cytochrome b can still generate ROS because ubisemiquinone can be generated. Indeed, we found that cells deficient in cytochrome b can generate ROS during hypoxia and stabilize HIF-1α protein [102] suggesting that ROS generation during hypoxia is dependent on oxygen-induced changes in the redox state of the electron transport chain. In contrast, depletion of RISP does not allow ROS generation or stabilization of HIF-1α protein in cells deficient in cytochrome b during hypoxia. Although there is strong genetic evidence to indicate that complex III participates in ROS generation during hypoxia to stabilize HIF-1α protein, the mechanism by which hypoxia stimulates ROS is not known.

ROS regulate tumorigenesis

A long-standing dogma in cancer is that the elevated ROS levels observed in tumors increase genomic instability resulting in progression of cancer [5, 104]. While the high levels of ROS can cause direct damage to the genome, lower levels of ROS might induce genomic instability through regulating signaling pathways. It is also possible that ROS may not regulate genomic instability at all in certain tumors but may regulate induction of genes that are required for tumorigenicity. In support of this premise, Chi Dang and colleagues recently demonstrated that in various MYC-driven cancers, the ability of commonly utilized antioxidants vitamin C and N-acetylcysteine to prevent tumorigenesis was due to diminishing HIF activity [105]. These investigators did not detect any genomic instability in Myc-driven cancers [105]. These results are consistent with the observation that overexpression of MnSOD prevents tumorigenesis of human melanoma cells and breast cancer cells in nude mice [106, 107] and MnSOD decreases hypoxic activation of HIF-1 [108]. These results are reinforced by the observation that NAC prevents tumorigenesis in a mouse model of constitutively active Rac1-driven Kaposi’s sarcoma by inhibiting AKT activation, HIF-1α protein induction, VEGF expression, and angiogenesis [109]. Thus, ROS activation of HIFs is likely another mechanism to induce tumorigenicity.

The confusion regarding ROS regulation of tumorigenesis comes from the observations that ROS can induce senescence or apoptosis. Tumor suppressors such as p53 engage senescence or apoptosis to limit tumor growth [110]. This raises the question as to why ROS do not trigger senescence or apoptosis in tumor cells. A plausible explanation is that tumor cells have mechanisms that evade ROS induction of senescence or apoptosis. Activation of Akt is sufficient to induce p19ARF and p16, p53 phosphorylation, and premature senescence [111]. In contrast, cells deficient in AKT were more resistant to oncogene-induced senescence [111]. These results suggest that the ROS are likely to be beneficial to cells with an activated oncogene only if the pathways of senescence are impaired. Indeed the loss of PTEN (increasing AKT activation) promotes senescence in a mouse model of prostate cancer, and invasive prostate cancer arises only when p53 is lost [112]. ROS induction of apoptosis would also need to be impaired for tumorigenesis. One mechanism that tumor cells utilize to evade ROS-induced apoptosis is to disengage ROS activation of p38α MAPK pathway [113]. ROS-stimulated p38 MAPK activity acts to induce apoptosis in wild-type MEFs. In contrast, MEFs deficient in p38α were resistant to ROS-induced apoptosis [113]. Interestingly, human cancer cell lines with high levels of ROS have impaired p38α activation [113]. Collectively, these studies indicate that tumor cells impair the p38α MAPK pathway and p53 pathway to evade ROS-dependent apoptosis and senescence, respectively, in order for tumorigenesis to proceed (Fig. 3).

ROS signaling in normal versus cancer cells. In normal cells, low levels of ROS can regulate controlled proliferation while high levels of ROS lead to cell death or senescence. Cancer cells with mutations in tumor suppressors can evade ROS induction of cell death or senescence. Thus, cancer cells exhibit high levels of ROS leading to uncontrolled cellular proliferation

Although the increase in ROS levels observed in cancer cells is causal for tumorigenesis, it might also provide a therapeutic potential to kill tumor cells. β-Phenylethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC), a natural compound known to increase intracellular ROS levels [114], preferentially killed ovarian epithelial cells transformed with the H-Ras(V12) oncogene or expression of Bcr-Abl oncogene in hematopoietic cells but not normal cell lines [115]. PEITC in vivo prolonged survival of mice injected with Ras-transformed ovarian epithelial cells suggesting that modulating ROS levels provides a potential therapeutic target for cancer. These findings were corroborated by the observation that mice injected with an ovarian cancer cell line expressing Akt activation showed reduction in tumor size after treatment with rapamycin and PEITC [111]. Rapamycin analogs are currently being used in clinical trials. One concern in using rapamycin analogs for cancer therapy is that they cause hyperactivation of Akt, which promotes resistance to therapeutic agents that induce apoptosis. The hyperactivation of AKT by rapamycin is unable to prevent oxidant-induced cell death by PEITC in cancer cells. Thus, PEITC or other compounds that promote ROS generation could be exploited for eradication of tumors with elevated AKT.

ROS regulate metastasis

Metastasis involves the displacement of tumor cells from their primary residence to the lymphatic and blood vessels where they circulate and eventually repopulate within normal tissue elsewhere in the body [116]. Epithelial tumor cells undergo a mesenchymal-like transition (EMT) during initiation of metastasis, which is characterized by loss of cell adhesion, repression of E-cadherin, and increased cell mobility [117]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) help detach primary tumor cells from extracellular matrix. Matrix metalloproteinases such as MMP3 can also cause EMT in cultured cells [118, 119]. ROS can both activate and induce gene expression of MMPs [120, 121]. Conversely, MMP3 induces expression of an alternately spliced form of Rac1b, which causes an increase in ROS production in mouse mammary epithelial cells [122]. The increase in ROS stimulates expression of the transcription factor Snail, which is sufficient to induce EMT [122]. Thus, ROS activation of EMT likely contributes to metastasis (Fig. 4).

ROS can induce tumor metastasis. ROS generated from the mitochondria under hypoxic conditions can activate HIF-1α, which can lead to subsequent activation of the transcription factor, TWIST, resulting in EMT. Mitochondrial ROS during hypoxia can inhibit GSK3β, resulting in upregulation of SNAIL. ROS are also generated from an alternate spliced variant of Rac1β, which leads to activation of the transcription factor, SNAIL, resulting in EMT

The other major regulator of metastasis is the hypoxic microenvironment [123]. The degree of hypoxia positively correlates with metastasis [124, 125]. Hypoxia stimulates EMT through multiple mechanisms including upregulation of HIF-1α, hepatocyte growth factor, Snail, and Twist [126]. Hypoxia in multiple cancer cell lines induces EMT by inhibiting the activity of GSK3β through generation of mitochondrial ROS [124]. This results in the upregulation of the EMT-inducing transcription factor Snail [127]. Additionally, ROS can modulate β-catenin signaling, which may provide a further mechanism in ROS regulation of EMT [128, 129]. To the extent that the mitochondrial ROS are required for activation of HIFs and inhibition of GSK3β, one can speculate that mitochondrial ROS are likely to be important regulators of metastasis.

Mutations in mitochondrial proteins increase tumorigenicity

Somatic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations have been observed in primary human cancers, but whether they are causal in tumorigenesis is not firmly established [130, 131]. Prostate cancers display a variety of mutations within the mitochondrial genome [132]. To test whether these mutations can increase tumorigenicity, Wallace and colleagues introduced mutations of ATP6, a component of complex V encoded by mitochondrial DNA, into the PC3 prostate cancer cell line. PC3 cells harboring the mutant ATP6 T8993G generated tumors seven times larger than PC3 cells harboring wild-type ATP6 [132]. Interestingly, this mutation increased ROS. However, the investigators did not test whether the increase in ROS due to the mutation was responsible for tumorigenesis [132]. The best evidence that mitochondrial mutations enhance tumorigenicity due to an increase in ROS comes from a case in which mtDNA from a mouse tumor cell line with poorly metastatic potential was replaced with mtDNA from a highly metastatic tumor cell line. The recipient tumor cells acquired the highly metastatic potential of the transferred mtDNA. The highly metastatic mtDNA exhibited complex I deficiency due to a mutation in NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6 (ND6), a subunit of complex I, which increased ROS production [133]. Furthermore, NAC inhibited the metastatic potential of these highly metastatic tumor cells indicating that mitochondrial mutations can increase metastasis through ROS [133].

Nuclear mutations of mitochondrial proteins in addition to mutations in mitochondrial DNA are associated with increase tumorigenicity [134]. Paraganglioma tumor cells harbor germline mutations in genes that encode the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) proteins. SDH is the only membrane-bound enzyme of the TCA cycle and is also a functional member (complex II) of the electron transport chain (ETC). SDH is a complex of four different polypeptides (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD) and several prosthetic groups that include FAD, non-haem iron (iron–sulphur centers), ubiquinone, and haemb [135]. Mutations in SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD genes have been associated with paraganglioma [136–138]. Loss of SDHD elevates HIF-1 under normoxia [139]. Interestingly, based on the structure and mechanism of complex II, it is predicted that mutations in SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD would increase ROS generation while mutations in SDHA would not [132]. Indeed, loss of SDHA protein by RNAi does not increase ROS, HIF activation, or tumorigenicity [140]. In contrast, loss of SDHB increases ROS production under normoxia triggering HIF-dependent tumorigenicity [140]. It is likely that the increase in ROS coupled with an increase in succinate levels cooperate to activate HIFs under normoxia [141]. The build-up of succinate would prevent the forward HIFα hydroxylation reaction. Recent evidence suggests mutations in the TCA cycle fumarate hydratase (FH) that are associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) also exhibit a ROS-dependent activation of HIF [142]. As more metabolic mutations are uncovered, we predict that loss of function mutations of mitochondrial proteins that increase ROS will increase tumorigenicity.

Conclusions

It is well documented that ROS are upregulated in tumors and can lead to aberrant induction of signaling networks that cause tumorigenesis and metastasis. Recent studies show that ROS have specific signaling pathways and transcription factors that play an important role in the initiation and progression of cancer. Antioxidants prevent tumorigenicity in part by preventing the activation of the transcription factor HIFs. The elevated ROS observed in tumor cells also represent a paradoxical therapeutic potential. Drugs that cause mild oxidative stress in normal cells are likely to further enhance ROS levels in cancer cells resulting in their death. The future is to design better drugs that work as antioxidants and prooxidants for cancer therapy as well elucidate the biological targets of ROS.

References

Trachootham D, Lu W, Ogasawara MA, Nilsa RD, Huang P (2008) Redox regulation of cell survival. Antioxid Redox Signal 10:1343–1374

Droge W (2002) Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev 82:47–95

Thannickal VJ, Fanburg BL (2000) Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279:L1005–L1028

Ames BN (1988) Measuring oxidative damage in humans: relation to cancer and ageing. IARC Sci Publ 40:7–16

Cerutti PA (1985) Prooxidant states and tumor promotion. Science 227:375–381

Storz P (2005) Reactive oxygen species in tumor progression. Front Biosci 10:1881–1896

Imlay JA, Chin SM, Linn S (1988) Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240:640–642

Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM (1992) Biologically relevant metal ion-dependent hydroxyl radical generation. An update. FEBS Lett 307:108–112

Suh YA, Arnold RS, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D, Chung AB, Griendling KK, Lambeth JD (1999) Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase Mox1. Nature 401:79–82

Lambeth JD (2004) NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol 4:181–189

Chanock SJ, el Benna J, Smith RM, Babior BM (1994) The respiratory burst oxidase. J Biol Chem 269:24519–24522

Babior BM (1999) NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood 93:1464–1476

Geiszt M, Kopp JB, Varnai P, Leto TL (2000) Identification of renox, an NAD(P)H oxidase in kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:8010–8014

Ago T, Kitazono T, Ooboshi H, Iyama T, Han YH, Takada J, Wakisaka M, Ibayashi S, Utsumi H, Iida M (2004) Nox4 as the major catalytic component of an endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase. Circulation 109:227–233

Arnold RS, Shi J, Murad E, Whalen AM, Sun CQ, Polavarapu R, Parthasarathy S, Petros JA, Lambeth JD (2001) Hydrogen peroxide mediates the cell growth and transformation caused by the mitogenic oxidase Nox1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:5550–5555

Arbiser JL, Petros J, Klafter R, Govindajaran B, McLaughlin ER, Brown LF, Cohen C, Moses M, Kilroy S, Arnold RS, Lambeth JD (2002) Reactive oxygen generated by Nox1 triggers the angiogenic switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:715–720

Li Q, Harraz MM, Zhou W, Zhang LN, Ding W, Zhang Y, Eggleston T, Yeaman C, Banfi B, Engelhardt JF (2006) Nox2 and Rac1 regulate H2O2-dependent recruitment of TRAF6 to endosomal interleukin-1 receptor complexes. Mol Cell Biol 26:140–154

Van Buul JD, Fernandez-Borja M, Anthony EC, Hordijk PL (2005) Expression and localization of NOX2 and NOX4 in primary human endothelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 7:308–317

Dong-Yun S, Yu-Ru D, Shan-Lin L, Ya-Dong Z, Lian W (2003) Redox stress regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis of human hepatoma through Akt protein phosphorylation. FEBS Lett 542:60–64

Turrens JF (2003) Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 552:335–344

Boveris A, Cadenas E, Stoppani AO (1976) Role of ubiquinone in the mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J 156:435–444

Cadenas E, Boveris A, Ragan CI, Stoppani AO (1977) Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys 180:248–257

Turrens JF, Alexandre A, Lehninger AL (1985) Ubisemiquinone is the electron donor for superoxide formation by complex III of heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys 237:408–414

Han D, Williams E, Cadenas E (2001) Mitochondrial respiratory chain-dependent generation of superoxide anion and its release into the intermembrane space. Biochem J 353:411–416

Starkov AA, Fiskum G (2001) Myxothiazol induces H2O2 production from mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 281:645–650

Muller FL, Liu Y, Van Remmen H (2004) Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem 279:49064–49073

Han D, Antunes F, Canali R, Rettori D, Cadenas E (2003) Voltage-dependent anion channels control the release of the superoxide anion from mitochondria to cytosol. J Biol Chem 278:5557–5563

Klimova T, Chandel NS (2008) Mitochondrial complex III regulates hypoxic activation of HIF. Cell Death Differ 15:660–666

Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF (1991) Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res 51:794–798

Irani K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ, Der CJ, Fearon ER, Sundaresan M, Finkel T, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ (1997) Mitogenic signaling mediated by oxidants in Ras-transformed fibroblasts. Science 275:1649–1652

Maciag A, Sithanandam G, Anderson LM (2004) Mutant K-rasV12 increases COX-2, peroxides and DNA damage in lung cells. Carcinogenesis 25:2231–2237

Nimnual AS, Taylor LJ, Bar-Sagi D (2003) Redox-dependent downregulation of Rho by Rac. Nat Cell Biol 5:236–241

Vafa O, Wade M, Kern S, Beeche M, Pandita TK, Hampton GM, Wahl GM (2002) c-Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene-induced genetic instability. Mol Cell 9:1031–1044

Kc S, Carcamo JM, Golde DW (2006) Antioxidants prevent oxidative DNA damage and cellular transformation elicited by the over-expression of c-MYC. Mutat Res 593:64–79

Tanaka H, Matsumura I, Ezoe S, Satoh Y, Sakamaki T, Albanese C, Machii T, Pestell RG, Kanakura Y (2002) E2F1 and c-Myc potentiate apoptosis through inhibition of NF-kappaB activity that facilitates MnSOD-mediated ROS elimination. Mol Cell 9:1017–1029

Murphy DJ, Junttila MR, Pouyet L, Karnezis A, Shchors K, Bui DA, Brown-Swigart L, Johnson L, Evan GI (2008) Distinct thresholds govern Myc’s biological output in vivo. Cancer Cell 14:447–457

Shachaf CM, Gentles AJ, Elchuri S, Sahoo D, Soen Y, Sharpe O, Perez OD, Chang M, Mitchel D, Robinson WH, Dill D, Nolan GP, Plevritis SK, Felsher DW (2008) Genomic and proteomic analysis reveals a threshold level of MYC required for tumor maintenance. Cancer Res 68:5132–5142

Meng TC, Fukada T, Tonks NK (2002) Reversible oxidation and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo. Mol Cell 9:387–399

Barrett WC, DeGnore JP, Keng YF, Zhang ZY, Yim MB, Chock PB (1999) Roles of superoxide radical anion in signal transduction mediated by reversible regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J Biol Chem 274:34543–34546

Zhang HJ, Zhao W, Venkataraman S, Robbins ME, Buettner GR, Kregel KC, Oberley LW (2002) Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 by overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells involves reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 277:20919–20926

Chiarugi P, Fiaschi T, Taddei ML, Talini D, Giannoni E, Raugei G, Ramponi G (2001) Two vicinal cysteines confer a peculiar redox regulation to low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase in response to platelet-derived growth factor receptor stimulation. J Biol Chem 276:33478–33487

Cumming RC, Lightfoot J, Beard K, Youssoufian H, O’Brien PJ, Buchwald M (2001) Fanconi anemia group C protein prevents apoptosis in hematopoietic cells through redox regulation of GSTP1. Nat Med 7:814–820

Berndt C, Lillig CH, Holmgren A (2007) Thiol-based mechanisms of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems: implications for diseases in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292:H1227–H1236

Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, Takeda K, Tobiume K, Sawada Y, Kawabata M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H (1998) Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J 17:2596–2606

Knebel A, Rahmsdorf HJ, Ullrich A, Herrlich P (1996) Dephosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases as target of regulation by radiation, oxidants or alkylating agents. EMBO J 15:5314–5325

Sachsenmaier C, Radler-Pohl A, Zinck R, Nordheim A, Herrlich P, Rahmsdorf HJ (1994) Involvement of growth factor receptors in the mammalian UVC response. Cell 78:963–972

Esposito F, Chirico G, Montesano Gesualdi N, Posadas I, Ammendola R, Russo T, Cirino G, Cimino F (2003) Protein kinase B activation by reactive oxygen species is independent of tyrosine kinase receptor phosphorylation and requires SRC activity. J Biol Chem 278:20828–20834

Ushio-Fukai M, Alexander RW, Akers M, Yin Q, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Griendling KK (1999) Reactive oxygen species mediate the activation of Akt/protein kinase B by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 274:22699–22704

Pages G, Lenormand P, L’Allemain G, Chambard JC, Meloche S, Pouyssegur J (1993) Mitogen-activated protein kinases p42mapk and p44mapk are required for fibroblast proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:8319–8323

Cowley S, Paterson H, Kemp P, Marshall CJ (1994) Activation of MAP kinase kinase is necessary and sufficient for PC12 differentiation and for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell 77:841–852

Cho SY, Klemke RL (2000) Extracellular-regulated kinase activation and CAS/Crk coupling regulate cell migration and suppress apoptosis during invasion of the extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol 149:223–236

van den Brink MR, Kapeller R, Pratt JC, Chang JH, Burakoff SJ (1999) The extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway is required for activation-induced cell death of T cells. J Biol Chem 274:11178–11185

Meloche S, Pouyssegur J (2007) The ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as a master regulator of the G1- to S-phase transition. Oncogene 26:3227–3239

Filmus J, Robles AI, Shi W, Wong MJ, Colombo LL, Conti CJ (1994) Induction of cyclin D1 overexpression by activated ras. Oncogene 9:3627–3633

Liu JJ, Chao JR, Jiang MC, Ng SY, Yen JJ, Yang-Yen HF (1995) Ras transformation results in an elevated level of cyclin D1 and acceleration of G1 progression in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol Cell Biol 15:3654–3663

Winston JT, Coats SR, Wang YZ, Pledger WJ (1996) Regulation of the cell cycle machinery by oncogenic ras. Oncogene 12:127–134

Albanese C, Johnson J, Watanabe G, Eklund N, Vu D, Arnold A, Pestell RG (1995) Transforming p21ras mutants and c-Ets-2 activate the cyclin D1 promoter through distinguishable regions. J Biol Chem 270:23589–23597

Lavoie JN, L’Allemain G, Brunet A, Muller R, Pouyssegur J (1996) Cyclin D1 expression is regulated positively by the p42/p44MAPK and negatively by the p38/HOGMAPK pathway. J Biol Chem 271:20608–20616

Weber JD, Raben DM, Phillips PJ, Baldassare JJ (1997) Sustained activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) is required for the continued expression of cyclin D1 in G1 phase. Biochem J 326(Pt 1):61–68

Balmanno K, Cook SJ (1999) Sustained MAP kinase activation is required for the expression of cyclin D1, p21Cip1 and a subset of AP-1 proteins in CCL39 cells. Oncogene 18:3085–3097

Pumiglia KM, Decker SJ (1997) Cell cycle arrest mediated by the MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:448–452

Sewing A, Wiseman B, Lloyd AC, Land H (1997) High-intensity Raf signal causes cell cycle arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol Cell Biol 17:5588–5597

Woods D, Parry D, Cherwinski H, Bosch E, Lees E, McMahon M (1997) Raf-induced proliferation or cell cycle arrest is determined by the level of Raf activity with arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol Cell Biol 17:5598–5611

Sarsour EH, Venkataraman S, Kalen AL, Oberley LW, Goswami PC (2008) Manganese superoxide dismutase activity regulates transitions between quiescent and proliferative growth. Aging Cell 7:405–417

Traore K, Sharma R, Thimmulappa RK, Watson WH, Biswal S, Trush MA (2008) Redox-regulation of Erk1/2-directed phosphatase by reactive oxygen species: role in signaling TPA-induced growth arrest in ML-1 cells. J Cell Physiol 216:276–285

Meng TC, Buckley DA, Galic S, Tiganis T, Tonks NK (2004) Regulation of insulin signaling through reversible oxidation of the protein–tyrosine phosphatases TC45 and PTP1B. J Biol Chem 279:37716–37725

Havens CG, Ho A, Yoshioka N, Dowdy SF (2006) Regulation of late G1/S phase transition and APC Cdh1 by reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell Biol 26:4701–4711

Cantley LC (2002) The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 296:1655–1657

Lawlor MA, Mora A, Ashby PR, Williams MR, Murray-Tait V, Malone L, Prescott AR, Lucocq JM, Alessi DR (2002) Essential role of PDK1 in regulating cell size and development in mice. EMBO J 21:3728–3738

Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM (2005) Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor–mTOR complex. Science 307:1098–1101

Cantley LC, Neel BG (1999) New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:4240–4245

Kandel ES, Hay N (1999) The regulation and activities of the multifunctional serine/threonine kinase Akt/PKB. Exp Cell Res 253:210–229

Shayesteh L, Lu Y, Kuo WL, Baldocchi R, Godfrey T, Collins C, Pinkel D, Powell B, Mills GB, Gray JW (1999) PIK3CA is implicated as an oncogene in ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 21:99–102

Downward J (2003) Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 3:11–22

Bae GU, Seo DW, Kwon HK, Lee HY, Hong S, Lee ZW, Ha KS, Lee HW, Han JW (1999) Hydrogen peroxide activates p70(S6k) signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 274:32596–32602

Nemoto S, Finkel T (2002) Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science 295:2450–2452

Lee SR, Yang KS, Kwon J, Lee C, Jeong W, Rhee SG (2002) Reversible inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J Biol Chem 277:20336–20342

Leslie NR, Bennett D, Lindsay YE, Stewart H, Gray A, Downes CP (2003) Redox regulation of PI 3-kinase signalling via inactivation of PTEN. EMBO J 22:5501–5510

Connor KM, Subbaram S, Regan KJ, Nelson KK, Mazurkiewicz JE, Bartholomew PJ, Aplin AE, Tai YT, Aguirre-Ghiso J, Flores SC, Melendez JA (2005) Mitochondrial H2O2 regulates the angiogenic phenotype via PTEN oxidation. J Biol Chem 280:16916–16924

Yellaturu CR, Bhanoori M, Neeli I, Rao GN (2002) N-Ethylmaleimide inhibits platelet-derived growth factor BB-stimulated Akt phosphorylation via activation of protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem 277:40148–40155

Trotman LC, Alimonti A, Scaglioni PP, Koutcher JA, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP (2006) Identification of a tumour suppressor network opposing nuclear Akt function. Nature 441:523–527

Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL (1995) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic–helix–loop–helix–PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:5510–5514

Bruick RK, McKnight SL (2001) A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science 294:1337–1340

Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O’Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ (2001) C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107:43–54

Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ (1999) The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399:271–275

Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando J, Ohh M, Salic A, Asara JM, Lane WS, Kaelin WG Jr (2001) HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 292:464–468

Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ (2001) Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292:468–472

Lando D, Peet DJ, Gorman JJ, Whelan DA, Whitelaw ML, Bruick RK (2002) FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev 16:1466–1471

Lando D, Peet DJ, Whelan DA, Gorman JJ, Whitelaw ML (2002) Asparagine hydroxylation of the HIF transactivation domain a hypoxic switch. Science 295:858–861

Mahon PC, Hirota K, Semenza GL (2001) FIH-1: a novel protein that interacts with HIF-1alpha and VHL to mediate repression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev 15:2675–2686

Denko NC (2008) Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer 8:705–713

Semenza GL (2003) Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 3:721–732

Patel SA, Simon MC (2008) Biology of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha in development and disease. Cell Death Differ 15:628–634

Bell EL, Emerling BM, Chandel NS (2005) Mitochondrial regulation of oxygen sensing. Mitochondrion 5:322–332

Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT (1998) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:11715–11720

Chandel NS, Schumacker PT (1999) Cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA (rho0) yield insight into physiological mechanisms. FEBS Lett 454:173–176

Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, Schumacker PT (2000) Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem 275:25130–25138

Agani FH, Pichiule P, Chavez JC, LaManna JC (2000) The role of mitochondria in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 expression during hypoxia. J Biol Chem 275:35863–35867

Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, Simon MC, Hammerling U, Schumacker PT (2005) Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab 1:401–408

Brunelle JK, Bell EL, Quesada NM, Vercauteren K, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, Scarpulla RC, Chandel NS (2005) Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab 1:409–414

Mansfield KD, Guzy RD, Pan Y, Young RM, Cash TP, Schumacker PT, Simon MC (2005) Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from loss of cytochrome c impairs cellular oxygen sensing and hypoxic HIF-alpha activation. Cell Metab 1:393–399

Bell EL, Klimova TA, Eisenbart J, Moraes CT, Murphy MP, Budinger GR, Chandel NS (2007) The Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signaling via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biol 177:1029–1036

Hunte C, Palsdottir H, Trumpower BL (2003) Protonmotive pathways and mechanisms in the cytochrome bc1 complex. FEBS Lett 545:39–46

Ames BN (1983) Dietary carcinogens and anticarcinogens. Oxygen radicals and degenerative diseases. Science 221:1256–1264

Gao P, Zhang H, Dinavahi R, Li F, Xiang Y, Raman V, Bhujwalla ZM, Felsher DW, Cheng L, Pevsner J, Lee LA, Semenza GL, Dang CV (2007) HIF-dependent antitumorigenic effect of antioxidants in vivo. Cancer Cell 12:230–238

Church SL, Grant JW, Ridnour LA, Oberley LW, Swanson PE, Meltzer PS, Trent JM (1993) Increased manganese superoxide dismutase expression suppresses the malignant phenotype of human melanoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:3113–3117

Li JJ, Oberley LW, St Clair DK, Ridnour LA, Oberley TD (1995) Phenotypic changes induced in human breast cancer cells by overexpression of manganese-containing superoxide dismutase. Oncogene 10:1989–2000

Kaewpila S, Venkataraman S, Buettner GR, Oberley LW (2008) Manganese superoxide dismutase modulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha induction via superoxide. Cancer Res 68:2781–2788

Ma Q, Cavallin LE, Yan B, Zhu S, Duran EM, Wang H, Hale LP, Dong C, Cesarman E, Mesri EA, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ (2009) Antitumorigenesis of antioxidants in a transgenic Rac1 model of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(21):8683–8688

Lowe SW, Cepero E, Evan G (2004) Intrinsic tumour suppression. Nature 432:307–315

Nogueira V, Park Y, Chen CC, Xu PZ, Chen ML, Tonic I, Unterman T, Hay N (2008) Akt determines replicative senescence and oxidative or oncogenic premature senescence and sensitizes cells to oxidative apoptosis. Cancer Cell 14:458–470

Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, Lin HK, Dotan ZA, Niki M, Koutcher JA, Scher HI, Ludwig T, Gerald W, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP (2005) Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature 436:725–730

Dolado I, Nebreda AR (2008) AKT and oxidative stress team up to kill cancer cells. Cancer Cell 14:427–429

Yu R, Mandlekar S, Harvey KJ, Ucker DS, Kong AN (1998) Chemopreventive isothiocyanates induce apoptosis and caspase-3-like protease activity. Cancer Res 58:402–408

Trachootham D, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Demizu Y, Chen Z, Pelicano H, Chiao PJ, Achanta G, Arlinghaus RB, Liu J, Huang P (2006) Selective killing of oncogenically transformed cells through a ROS-mediated mechanism by beta-phenylethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Cell 10:241–252

Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massague J (2009) Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer 9:274–284

Polyak K, Weinberg RA (2009) Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer 9:265–273

Sternlicht MD, Lochter A, Sympson CJ, Huey B, Rougier JP, Gray JW, Pinkel D, Bissell MJ, Werb Z (1999) The stromal proteinase MMP3/stromelysin-1 promotes mammary carcinogenesis. Cell 98:137–146

Lochter A, Srebrow A, Sympson CJ, Terracio N, Werb Z, Bissell MJ (1997) Misregulation of stromelysin-1 expression in mouse mammary tumor cells accompanies acquisition of stromelysin-1-dependent invasive properties. J Biol Chem 272:5007–5015

Belkhiri A, Richards C, Whaley M, McQueen SA, Orr FW (1997) Increased expression of activated matrix metalloproteinase-2 by human endothelial cells after sublethal H2O2 exposure. Lab Invest 77:533–539

Nelson KK, Melendez JA (2004) Mitochondrial redox control of matrix metalloproteinases. Free Radical Biol Med 37:768–784

Radisky DC, Levy DD, Littlepage LE, Liu H, Nelson CM, Fata JE, Leake D, Godden EL, Albertson DG, Nieto MA, Werb Z, Bissell MJ (2005) Rac1b and reactive oxygen species mediate MMP-3-induced EMT and genomic instability. Nature 436:123–127

Galluzzo M, Pennacchietti S, Rosano S, Comoglio PM, Michieli P (2009) Prevention of hypoxia by myoglobin expression in human tumor cells promotes differentiation and inhibits metastasis. J Clin Invest 119:865–875

Vaupel P, Schlenger K, Knoop C, Hockel M (1991) Oxygenation of human tumors: evaluation of tissue oxygen distribution in breast cancers by computerized O2 tension measurements. Cancer Res 51:3316–3322

Vaupel P, Hockel M, Mayer A (2007) Detection and characterization of tumor hypoxia using pO2 histography. Antioxid Redox Signal 9:1221–1235

Gort EH, Groot AJ, van der Wall E, van Diest PJ, Vooijs MA (2008) Hypoxic regulation of metastasis via hypoxia-inducible factors. Curr Mol Med 8:60–67

Cannito S, Novo E, Compagnone A, Valfre di Bonzo L, Busletta C, Zamara E, Paternostro C, Povero D, Bandino A, Bozzo F, Cravanzola C, Bravoco V, Colombatto S, Parola M (2008) Redox mechanisms switch on hypoxia-dependent epithelial–mesenchymal transition in cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 29:2267–2278

Essers MA, de Vries-Smits LM, Barker N, Polderman PE, Burgering BM, Korswagen HC (2005) Functional interaction between beta-catenin and FOXO in oxidative stress signaling. Science 308:1181–1184

Funato Y, Michiue T, Asashima M, Miki H (2006) The thioredoxin-related redox-regulating protein nucleoredoxin inhibits Wnt-beta-catenin signalling through dishevelled. Nat Cell Biol 8:501–508

Polyak K, Li Y, Zhu H, Lengauer C, Willson JK, Markowitz SD, Trush MA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (1998) Somatic mutations of the mitochondrial genome in human colorectal tumours. Nat Genet 20:291–293

Chatterjee A, Mambo E, Sidransky D (2006) Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human cancer. Oncogene 25:4663–4674

Petros JA, Baumann AK, Ruiz-Pesini E, Amin MB, Sun CQ, Hall J, Lim S, Issa MM, Flanders WD, Hosseini SH, Marshall FF, Wallace DC (2005) mtDNA mutations increase tumorigenicity in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:719–724

Ishikawa K, Takenaga K, Akimoto M, Koshikawa N, Yamaguchi A, Imanishi H, Nakada K, Honma Y, Hayashi J (2008) ROS-generating mitochondrial DNA mutations can regulate tumor cell metastasis. Science 320:661–664

Gottlieb E, Tomlinson IP (2005) Mitochondrial tumour suppressors: a genetic and biochemical update. Nat Rev Cancer 5:857–866

Yankovskaya V, Horsefield R, Tornroth S, Luna-Chavez C, Miyoshi H, Leger C, Byrne B, Cecchini G, Iwata S (2003) Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science 299:700–704

Astuti D, Latif F, Dallol A, Dahia PL, Douglas F, George E, Skoldberg F, Husebye ES, Eng C, Maher ER (2001) Gene mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase subunit SDHB cause susceptibility to familial pheochromocytoma and to familial paraganglioma. Am J Hum Genet 69:49–54

Baysal BE, Ferrell RE, Willett-Brozick JE, Lawrence EC, Myssiorek D, Bosch A, van der Mey A, Taschner PE, Rubinstein WS, Myers EN, Richard CW 3rd, Cornelisse CJ, Devilee P, Devlin B (2000) Mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in hereditary paraganglioma. Science 287:848–851

Baysal BE, Willett-Brozick JE, Lawrence EC, Drovdlic CM, Savul SA, McLeod DR, Yee HA, Brackmann DE, Slattery WH 3rd, Myers EN, Ferrell RE, Rubinstein WS (2002) Prevalence of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD germline mutations in clinic patients with head and neck paragangliomas. J Med Genet 39:178–183

Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, Gottlieb E (2005) Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell 7:77–85

Guzy RD, Sharma B, Bell E, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT (2008) Loss of the SdhB, but not the SdhA, subunit of complex II triggers reactive oxygen species-dependent hypoxia-inducible factor activation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol 28:718–731

Pollard PJ, Briere JJ, Alam NA, Barwell J, Barclay E, Wortham NC, Hunt T, Mitchell M, Olpin S, Moat SJ, Hargreaves IP, Heales SJ, Chung YL, Griffiths JR, Dalgleish A, McGrath JA, Gleeson MJ, Hodgson SV, Poulsom R, Rustin P, Tomlinson IP (2005) Accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates and over-expression of HIF1alpha in tumours which result from germline FH and SDH mutations. Hum Mol Genet 14:2231–2239

Sudarshan S, Sourbier C, Kong HS, Block K, Romero VV, Yang Y, Galindo C, Mollapour M, Scroggins B, Goode N, Lee MJ, Gourlay CW, Trepel J, Linehan WM, Neckers L (2009) Fumarate hydratase deficiency in renal cancer induces glycolytic addiction and HIF-1α stabilization by glucose-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell Biol. doi:10.1128/MCB.00483-09

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01CA123067-03 as well as the LUNGevity Foundation and a Consortium of Independent Lung Health Organizations convened by the Respiratory Health Association of Metropolitan Chicago to N.S.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weinberg, F., Chandel, N.S. Reactive oxygen species-dependent signaling regulates cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 3663–3673 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-0099-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-0099-y