Abstract

The promotion and use of green products is an important way to improve the living environment and reduce resource consumption and waste. Green products often have higher prices than general products due to its green attributes. According to the signal theory, purchasing green products can effectively convey the pro-social signals of the consumers. Therefore, based on the price premium characteristics of green products, this study constructed a theoretical and quantitative research model of the public’s WTP (willingness to pay) a price premium for green products and conducted an in-depth study on the consumers’ acceptability of premium for green products. A total of 991 valid questionnaires were analyzed, and the following results were obtained: (1) The public’s WTP a price premium for green products was generally low, with only 30.1% of respondents. (2) The influencing factors of the WTP a price premium for green products were conditional value>green value>functional value>value expression form>price importance. Economic factors were still the main reason that hinders the public’s WTP a price premium for green products. When the premium conveys public’s pro-social and pro-environmental signal characteristics, it could effectively improve the public’s acceptability of premium for green products. (3) The public’s WTP a price premium for green products varied with marital status, education level, working years, monthly income, and occupation characteristics. The public who were married, had a master’s degree or above, and had worked for 1 year or less and whose disposable monthly income was more than 50,000 yuan and whose occupation was engineers and technicians had the highest WTP a price premium for green products. (4) Policy guidance and media publicity had a positive moderating effect on the path of influencing factors on the WTP for green products. On this basis, this study proposes to deepen the exemplary leading role of the government and attach importance to the education and publicity function of green consumption consciousness. Enterprises should give full play to the influence of reference groups, highlight the value of green products, and popularize green products through appropriate price discount activities, so as to promote the public to participate more actively in the purchase of green products. At the same time, it can also provide reference and enlightenment for the formulation of relevant policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The rapid economic growth has facilitated the exploitation and excessive consumption of natural resources, leading to environmental degradation, with widespread consequences such as global warming, environmental degradation (soil, air, and water), ozone depletion, and life-threatening health hazards (Scheel et al. 2020). The energy consumption and carbon emission caused by the consumption side are gradually increasing (Li et al. 2017). Green consumption is considered as a practical need to alleviate the pressure of resources and environment and, to some extent, promote the sustainable development of social economy (Ali and Onur 2020). In recent years, the government has vigorously advocated green lifestyle, and the public’s awareness of green consumption has been constantly improved. Green products are increasingly favored by consumers due to their environmental protection, energy saving, health, and other characteristics(Zhang et al. 2018). However, existing studies indicate that consumers’ positive attitude toward green products cannot be effectively transformed into actual purchasing behavior (Babutsidze and Chai 2018; Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002).

Compared with general products, green products use natural materials or recyclable materials in the production stage and have lower energy consumption in the use stage. In addition, the purchase of green processing equipment and the acquisition of green product certification can all lead to an increase in the cost of green products, so the price of green products is higher than that of general products (Peattie 2010). Even if some green products (such as energy-efficient refrigerators) can save money in the long run, they are more costly when purchased (Joshi and Rahman 2015). From the perspective of value pricing, green products get a price premium because they provide green value to consumers. However, consumers who buy green products are not direct beneficiaries, and the green value is reflected in the improvement of the whole social environment, leading to a significant reduction in consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) a premium for green products (Schuitema and Groot 2015).

Existing research shows the price and quality of green products (functional value) (Suki 2016; Khan and Mohsin 2017), the emotion generated by positive experience in the purchase process (emotional value) (Wang et al. 2015), the need to seek knowledge (cognitive value) (Biswas and Roy 2015), the impact of promotional activities and subsidies (conditional value) (Goncalves et al. 2016), and the desire to demonstrate environmental protection (environmental value) (Laroche et al. 2013) may have a powerful impact and predict green consumption behavior accordingly. Although consumers’ green purchasing behavior is mainly driven by product value, it is also influenced by internal factors such as individual values, beliefs, attitudes, and social norms (Cheung and To 2019; Lin and Niu 2018), as well as external factors such as economic stimulus, information stimulus, and regulations (Darby 2006; Hahnel et al. 2015; Moloney and Strengers 2014). Previous studies mostly studied consumers’ rational preference and stable attitude toward green products from the perspective of consumer motivation, attitudes, values, and external pressures, so as to enhance consumers’ premium acceptability and willingness to purchase green products (Abdullahv et al. 2018). Signal theory holds that the green signal of green products allows consumers to display their ideal personal characteristics, such as pro-environmental characteristics and pro-social values through product consumption. Such signals can help consumers gain advantages in social interaction and as an additional incentive, pay premium for environmental protection products (Berger 2017). Lack of information is an important factor hindering green consumer behavior (Young et al. 2010). In response to lack of information, reference groups are important channels for individuals to obtain relevant consumer knowledge, which will significantly affect consumers’ green purchasing behavior (Sparks and Shepherd 1992). Therefore, this study will focus on the premium characteristics of green products and clarify the current status and influencing factors of the public’s WTP a price premium for green products. With premium as a green signal or quality assurance signal, explore the differences in demographic characteristics of WTP and the role of situational factors.

On the basis of these studies, this study establishes a theoretical framework including value perception, price sensitivity, reference group, and other factors and explores the influencing factors of the public’s WTP a price premium for green products, thereby expanding existing research. On the one hand, this study identifies the key factors that affect consumers’ purchase of green products from the perspective of the acceptability of premium, in order to explore the public’s psychological process of paying price premiums for green products, and improves the public’s acceptability and willingness to purchase green products, so as to provide theoretical support for promoting universal green consumption. On the other hand, it promotes green development from the consumption side, promotes social ecological progress, and provides reference for the decision-making and policy arrangement of relevant departments.

Literature review

Green product premium

Green product is mainly defined from three perspectives. The first is from the perspective of product life cycle. To judge whether a product is green, it should start from the whole product cycle including the process of product composition source, production, transportation, actual consumption, and disposal to evaluate the environmental emissions and energy consumption of products to air, soil, or water and related problems (Sun et al. 2018; Wu 2014). The second is from the view of consumer perception. If consumers have a positive green perception of the product and the green perception is not green in nature, the product is green (Wang et al. 2018). The third is from the perspective of technical certification. Products with environmental protection marks certified by relevant authorities are considered as green products (Zhang 2018).

The price of green products is often higher than the general products due to its green attributes. Price premium refers to prices that generate higher than average profits (Drozdenko et al. 2011). Green product premium refers to the portion that consumers pay for green products in excess of their use value and used for green attributes (Zong et al. 2014). When the seller of normally high-quality products can charge a price higher than the lowest average price of high-quality products, the difference between the high price and the competitive price can be regarded as the price premium (Rao and Monroe 1988). Consumers’ WTP refers to the maximum amount that consumers are willing to spend for products or services (Whitehead 2000). In recent years, more and more researches have focused on the willingness to pay and influencing factors of green products. For example, buyers of low-emission hybrid vehicles are willing to pay high prices for reducing global CO2 emissions (Delgado et al. 2015; Thaler and Sunstein 2009).

Signal theory

The root of the signal is “information asymmetry” (that is, the deviation from perfect information). One party involved in market transactions has more information than the other (Bergh et al. 2018). How to reduce the information asymmetry between the two parties has become the most basic research problem of signal theory (Spence 2002). In the evaluation process before purchasing green products, it is difficult for the buyer to obtain symmetrical information and make objective judgments if the other party does not provide complete and adequate information (Priest 2009). When consumers face the problem of information asymmetry, they are more concerned about how to evaluate the “quality” of products (Kirmani & Rao, 1997). Signal theory holds that the party with information advantage can reduce information asymmetry by transmitting effective information to the outside world in order to avoid adverse selection of the party with information disadvantage (Ruey-Jer et al. 2021). As an internal insider, signaler usually owns information about individuals, products, or organizations that cannot be known by outsiders (Spence 1978). The receiver is usually defined as an external person who wishes to obtain internal information about individuals, products, organizations, etc., but often cannot do so directly (Basuroy et al. 2006). If there exists a social or economic exchange between the receiver and the signaler, and the signaler really has the underlying desired qualities, both sides can benefit. However, there is often a partial conflict of interest between signaler and receiver (Gupta 2021). A signal must be valid, otherwise a reasonable receiver will ignore it and refuse to communicate with the signaler. Information that can convey useful content is usually regarded as an “effective signal.” The signal is reliable only if the individual with the required quality is capable or willing to bear the cost of producing the signal.

The influencing factors of WTP

Green product value

The value of a product is what consumers purchase and consume. When consumers purchase a product, they may first perceive the value of the product, then measure whether they are willing to pay for the product, and finally make a choice (Yu and Lee 2019; Ogiemwonyi et al. 2020). According to the theory of consumption value, consumers will be influenced by five core factors, functional value, conditional value, social value, emotional value, and cognitive value, when they make product purchase choices (Sheth et al. 1991).

The consumption value theory has been applied and tested in many applications, and it has been well predicted. Some scholars have also applied it to the research field of green products to study how consumption value of green products affects consumers’ perception of green product performance. Functional value of products, such as durability, reliability, price, and quality (Lin and Huang 2012), is the main driving factor for consumer choice behavior in green product purchasing decision (Bei and Simpson 1995). Green value involves the relationship between environment and development. With the enhancement of the sense of environmental protection, consumers have changed their consumption patterns, which has turned to be green (Kilbourne and Pickett 2008). People with high environmental responsibility are more likely to trigger green purchasing decisions (Wang et al. 2014). Emotional value refers to the perceived utility obtained from the product’s ability to evoke feelings or emotional states. Green products will benefit people’s physical health and environmental ecology, thus making consumers feel happy (Wang et al. 2015). The higher the emotional value perceived by consumers, the stronger the consumer’s intention to repurchase green products (Goncalves et al. 2016). Conditional value refers to the perceived utility from the product as a decision-maker in the outcome of a particular situation. When the use of a product or service is closely related to a specific situation, the conditional value of the product is generated and influences consumers’ green product selection behavior (2010; Niemeyer 2010; Gadenne et al. 2011).

Price sensitivity

Price is an important factor in the green consumer market (Yadav and Pathak 2017). From the perspective of economics, price sensitivity is the highest price that an individual is willing to pay for a certain commodity in order to purchase the required quantity, which is also known as the reserve price (Yun and Hanson 2020). When price sensitivity extends to the research field of consumer behavior, it is defined as the degree of perception and response of individuals to price changes (or differences) of products (or services) (Sana 2020). Price sensitivity focuses on individual responses to price and price changes, including dimensions such as price importance and price search tendency (Sheng et al. 2019).

The price elasticity of demand for green products is relatively high, so consumers are more sensitive to the price of green products. Due to the relatively high production cost and production technology of green products and the relatively high cost of market development, their prices are relatively high. Due to the limited purchasing power of consumers, it may further reduce green consumption (Wang et al. 2015). As the change in demand concepts, the public commonly recognizes that the cost of green consumer products is higher than that of general products, which is an established fact. Therefore, they are willing to pay a higher price than general products to buy green products, within 10% of the price (Cicia et al. 2002).

Reference group

In the context of consumption, reference group refers to the individuals or groups used for comparison, reference, and imitation in consumption decision-making, which affects consumers’ attitudes, ideas, and purchasing behavior. Reference group, as the related group with the most contacts and the closest relationship with consumers, is the social relationship that consumers attach most importance to. It plays a crucial role in consumers’ purchase behavior and willingness (Childers and Rao 1992). Reference group influence is a multidimensional construct and includes three dimensions of informational influence, normative influence, and value-expressive influence, which are generally accepted by the academic circle at present (Park and Lessig 1977; Bearden et al. 1989; Audia et al. 2020). Informational influence refers to that in a specific consumption situation, consumers try to search for information related to products from relevant people in order to reduce risks or gain more knowledge and ability, thus influencing their purchasing behavior. Normative influence refers to the influence of individuals on their purchasing choices in order to comply with the preferences and expectations of other individuals or groups to gain appreciation or avoid punishment. Value-expressive influence is reflected in the motivation of individuals to improve their self-image by establishing associations with positive references and disassociating from negative ones and expressing their own values through consistency with the reference group (Jia et al. 2008).

Consumers’ green purchasing behaviors are proved to be influenced by the reference group (Zhang and Du 2009). Reference group is an important external cue for consumers to make decisions. Welsch and Kühling (2009) found that the consumption patterns of the reference group significantly affected consumers’ pro-environment purchasing behaviors. Gupta and Ogden (2009) found that the reference group has a strong influence on green purchase when analyzing the attitudinal-behavioral gap of green purchase. Chen and Peng (2014) studied the influence of reference groups on consumers’ green consumption attitude behavior gap with the method of literature analysis.

Method

Variable measurement

According to the analysis framework of this research, the questionnaire is divided into four parts. The first part is the social demographic characteristics of the interviewee, such as gender, age, and other basic information. The second part aims to understand the factors affecting the WTP a price premium for green product. The fourth part discusses the role of situational factors.

The value perception of green products is measured from four aspects: functional value, emotional value, conditional value, and green value. Functional value is referred to Biswas and Roy’s scale (Biswas and Roy 2015), emotional value and conditional value are referred to Lin and Huang’s scale (Lin & Huang), and green value is referred to Yang and Zhou’s scale (Ge et al. 2020). Price sensitivity is measured in terms of price importance and price search propensity. The importance of price refers to the scale developed by Sinha and Batra (1999), which contains 4 items. The price search intention uses the scale of Lichtenstein et al. (1993), which has a total of 4 items. The reference group is measured from normative influence, informational influence, and value-expressive influence, referring to the scale of Park and Lessig (1977). All items are calculated using a five-level Likert scale, ranging from 1 for “completely disagree” to 5 for “completely agree.”

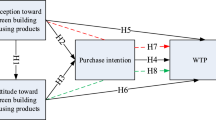

It is assumed that the value of green products, price sensitivity, and reference groups all have significant influences on the WTP a price premium for green products, and situational factors play a moderating role. The willingness to pay for green products has significant differences in social demographic variables. The research model is shown in Fig. 1.

Sample selection and data acquisition

In order to test the reliability of the scale, this study conducted a pre-survey of representative urban residents from April to May 2020, which was aimed to evaluate the quality of the initial questionnaire and to modify the questionnaire items, thus obtaining the formal survey questionnaire. The pre-survey is mainly carried out by issuing paper questionnaires and entrusting family members and friends to send them to their colleagues and friends to improve the data quality and reliability. A total of 211 valid questionnaires were collected, with an effective response rate of 89.8%. The sample size meets the basic requirements of scientific research. We reviewed the responses to the questionnaire we received and deleted those who had the same answers to the main different variables and those who responded in a short time compared to others. According to the descriptive analysis of the statistical variables of the valid questionnaire, the ratio of male to female was 47.4% and 52.6%. respectively. The age distribution in the sample is relatively even, mainly concentrated in the 20–40 years old stage; the proportion of the 26–30 years old population reaches 32.3%, followed by the 21–25-year-old and 31–35-year-old population, with which the proportions are respectively 21.3% and 20.9%. In addition, the survey samples involve different educational backgrounds, occupations, and monthly income levels, and the samples are fairly representative.

Before issuing the formal questionnaire, we used random and resampling methods to select respondents of different ages, genders, and educational background to ensure the diverse, representative, and scientific nature of the sample. We issued the questionnaire online via “questionnaire star,” which is a Chinese professional questionnaire survey software. To ensure the quality of the questionnaire answers, we distributed red packets on the “questionnaire star” by forwarding the questionnaire link, scanning the questionnaire QR code, and distributing them by means of WeChat, QQ, and other communication platforms. In the process of investigation, we explained the purpose of the survey to the respondents and explained that the survey results were only used for scientific research and personal information would not be disclosed and emphasized the importance of filling in the questionnaire carefully. A total of 1065 questionnaires were collected, and 991 valid questionnaires (87.51%) were determined after deleting the questionnaires that lacked options or more than eight consecutive choices, and the answer time was less than 4 min. The sample structure distribution of the formal survey is shown in Table 1.

In terms of gender, the ratio of male to female was relatively balanced. In terms of age, 47.6% were aged between 21 and 25, and 19.4% were aged between 26 and 30. A total of 45.3 % of the respondents were college students, and 52.5% reported a monthly income of more than 5000 yuan. By comparing early and late respondents (compare the mean of the first quartile and the last quartile of the respondents for all variables) to check for non-response bias, no significant difference (p> 0.10) appeared. Therefore, non-response deviation is not the main focus of our analysis.

Reliability and validity analysis

This study conducted a preliminary survey containing a total of 211 questionnaires to test the validity of the initial scale. We first carried out exploratory factor analysis of value perception, price sensitivity, reference group, and willingness to pay a price premium. KMO value, Bartlett sphericity test, principal component analysis method, and maximum variance method were used. KMO values were 0.74, 0.733, and 0.815 respectively, and Bartlett sphericity test results were 616.96, 861.105, and 1934.162, which were suitable for factor analysis. Then we made principal component analysis on the scale and found that the load values of items A2, B6, and B8 on each factor were less than 0.5. After deleting these three items, we conducted factor analysis on the scale again. The extracted values of common factor variance were all greater than 0.5, and the main factor questions formed after rotation were all more than two. The formal scale was finally formed after the items were revised.

The assessment of the scale reliability mainly included two parts: the overall reliability of the scale and the reliability of latent variables. Cronbach’s α value (>0.6) was used to test the overall reliability of the scale, as well as Cronbach’s α value and CR (>0.6) to test the reliability of latent variables. After analyzing the data, it was found that overall Cronbach’s values of the three scales were 0.71, 0.82, and 0.74, respectively, which were all greater than 0.7, indicating that the overall scale was reliable. Among them, Cronbach’s values of each latent variable ranged from 0.624 to 0.842, and the CR values were between 2.341 and 11.234, which were all within acceptable standards, indicating that the scale passed the reliability test

The evaluation of scale validity mainly included content validity and structure validity. Content validity was mostly controlled by qualitative methods. The verification of structure validity mainly examined the convergence validity and discriminative validity of the scale. This study strictly followed the scale development procedure and invited a professor and four doctoral students to discuss the questionnaire design repeatedly on the basis of a large number of literature studies. The content validity of this scale was good and met the requirements of scientific research. In addition, the standardized load of the items in the scale on the corresponding latent variables was greater than 0.5 and reached the significance level, and the corresponding AVE value was between 0.501 and 0.82, which met the requirement of AVE > 0.5, indicating a good convergence validity of the scale. In addition, the square root of AVE of latent variables was all greater than the correlation coefficient between latent variables, indicating that the potential structure of the variables was well distinguished, and the scale passed the validity test.

Data analysis and results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

We conducted a descriptive statistical analysis of the research, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 showed that the overall mean of the public’s WTP a price premium for green products exceeds 3 (M=3.38), and only 30.1% of respondents were WTP a price premium for green products. The proportion of respondents who are most unwilling, willing, and general to pay a price premium for green products accounted for the vast majority, reaching 10.5%, 19.4%, and 40.1%, respectively, reflecting that the public’s WTP a price premium for green products was at a low level and needed to be raised. In terms of factors affecting the public’s WTP for green products, the mean of value perception was the highest (M=3.67), and the lowest is the reference group (M=3.38). Among the subdimensions of value perception, the mean of green value perception is the highest (M=3.79), indicating that the public had the most obvious perception of environmental protection of green products.

Through further analysis of the correlation of variables, it was found that value perception, price sensitivity, and reference groups were significantly correlated with WTP a price premium, among which emotional value perception had the highest correlation with WTP a price premium (r = 0.678, P < 0.01), followed by green value perception (r = 0.655, P < 0.01), and normative influence was the lowest (r = 0.097, P < 0.01), supporting the following analysis initially.

Variance analysis

This study used one-way ANOVA to test whether there was a significant difference in social demographic characteristics of WTP a price premium for green products (Table 3). The results demonstrated that there were significant differences in the public’s WTP a price premium for green products in terms of marital status, education level, working years, monthly income, and occupation. Specifically, in terms of marital status and WTP a price premium, the mean value of married people was 3.514, higher than the mean value of 3.379, and the mean value of unmarried people was 3.314, lower than the mean value. ANOVA analysis showed that the significance level was P=0.001<0.05, indicating a significant impact on the WTP a price premium for green products. Similarly, we found that there were significant differences in education (P = 0.002), working years (P = 0.007), monthly income (P = 0.044), and occupation (P = 0.003). Through the ANOVA analysis of the above sociodemographic variables, it can be seen that the significance level is less than 0.05, and the multiple analysis results further show the public who were married, had master’s degree or above, and had working years of 1 year or less and whose disposable monthly income was above 50,000 yuan and whose occupations were engineering and technical personnel had the highest WTP a price premium for green products.

Regression model analysis

This study used the multifactor line regression method to explore the predictive power of different influencing factors on the WTP a price premium for green products. This study selected gender, age, marital status, education level, working years, and monthly income as control variables and regressed the dependent variable WTP a price premium with the independent variable. The regression analysis results are shown in Table 4.

According to P value and adjusted R2 value, the significance level and explanatory power of the regression model were relatively good. In addition, in order to solve the situation confusion problem of regression analysis, this study introduced tolerance to detect multiple collinearity among independent variables. Here, the tolerance value was between 0.517 and 0.823, far greater than the threshold index of 0.1, indicating that there was no multiple collinearity problem between the respective variables. At the significance level of 0.05, five variables (functional value, conditional value, green value, price importance, and value expression) were all lower than the threshold value, indicating that they had a significant impact on the WTP a price premium for green products. However, the P values of the four variables (emotional value, price search tendency, normative influence, and informational influence) were all larger than the threshold value, indicating that they had no influence on the WTP a price premium for green products. Moreover, according to the standardization coefficient of the model, the conditional value (β=−0.099) was the most important factor affecting the public’s willingness to pay a price premium for green products, while the standardized coefficient of green value was 0.079, which showed that it was the main factor influencing the willingness to pay a price premium for green products.

Moderating effect analysis

In this study, hierarchical linear regression was used to test the moderating effects of policy guidance and media publicity on the relationship between value perception, price sensitivity, reference group, and the WTP a price premium (Fang et al. 2015) [65]. Firstly, we tested the role of the value perception, price sensitivity, and the reference group on the willingness to pay a price premium, while controlling demographic variables. Secondly, two moderating variables (policy guidance and media publicity) were added to the model, and the impact of interaction terms was tested finally. In the trial of multiple models, the following models were verified to be significant, with the results shown in Tables 5 and 6.

It could be found that policy guidance had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between emotional value, conditional value, green value, normative influence, value-expressive influence, and WTP a price premium for green products. The P value of the multilayer regression analysis model was less than 0.05 in Table 5, which was statistically significant. The interaction terms of policy guidance and emotional value, conditional value, green value, normative influence, and value-expressive influence were significant, and the coefficients were 0.065, 0.579, 0.371, 0.417, and 0.563, indicating that policy guidance had a positive moderating effect on the path of these variables on the WTP a price premium for green product.

Similarly, media publicity had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between functional value, emotional value, conditional value, green value, normative influence, and willingness to pay a price premium for green products. The P value of the multilayer regression analysis model was less than 0.05 in Table 6, which was statistically significant. The interaction terms of media publicity and functional value, emotional value, conditional value, green value, and normative influence were significant, and the coefficients were 0.363, 0.324, 0.842, 0.390, and 0.436, indicating that media publicity had a positive moderating effect on the path of these variables on the willingness to pay a price premium for green product.

Discussion

=Although green products can save energy and provide a good living environment, many green products are more expensive than non-green products, especially when they enter the market (Chekima et al. 2016). This green premium is a key challenge faced by the promotion and practice of green products widely (Peattie 2010; Zhang et al. 2019), and it is still difficult to improve the public’s acceptance and purchase intention of green products premium.

This study found that the public’s perception of conditioned value and green value perception of green products have the greatest impact on the WTP a price premium. That is to say, economic factors are still the main reason to hinder the public’s WTP a price premium for green products, which has significant economic subsidy effect. When green products have subsidies, promotions, or discount activities, the willingness to pay a price premium is higher (Ghosh et al. 2021). Existing research confirms that the change of situational variables will affect the purchase of green products under certain circumstances (Niemeyer 2010; Gadenne et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2019). Due to personal price sensitivity, when green products offer discounts or subsidies, their conditional value will increase, which will eventually increase the willingness of consumers to pay premiums for green products (Biswas and Roy 2015).

Existing research shows that consumers have higher expectations for green products if they are clearly identified as ecologically green. Signal theory points out that consumers face information asymmetry and evaluate products and services based on incomplete and misleading information (Chang et al. 2020). When dealing with interactions involving asymmetric information, the signaler is allowed to try to persuade the signal receiver and convey a certain personal trait through observable information about the purchase behavior of goods. In such a situation, green consumers are considered more pro-social (Griskevicius et al. 2010). Signaler can thus gain advantages in social interaction, which can be served as additional incentives to purchase environmentally friendly products (Guo et al. 2020). The form of green label or certification can give consumers some confidence in the credibility of these statements and help build consumer trust (Atkinson and Rosenthal 2014). Consumers rely on signals to conduct internal cognition and finally decide whether to buy green products in this asymmetric information environment.

In this study, the normative influence and informational influence of the reference group have no significant influence on the WTP a price premium, which may be because whether the Chinese people choose green products in consumption is generally not significantly affected by other people’s pressure or social ethos. The current phenomenon of buying green products has not yet formed a wave of purchase by the whole people (Ren et al. 2020). The public does not fully agree with the social norms for buying green products, and as influenced by the golden mean, the Chinese public generally avoids expressing strong appreciation or criticism for the actions of others (Jie et al. 2019). As a result, consumers’ motivation to comply with other people’s preferences or group pressure in order to obtain appreciation or avoid punishment is slightly insufficient, and the normative influence of reference groups cannot play a role. Informational influence refers to the public’s search for all kinds of information related to products before consumption to obtain more relevant knowledge. As the current purchasing mechanism of green products is not yet mature and the green product information is not perfect, the public often lacks understanding of it (Ohtomo and Hirose 2007; Rousseau and Vranken 2013), which results in the informational influence of the reference group not significantly affecting the willingness to pay a price premium.

Conclusions and policy implications

Research conclusions

Improving the public’s acceptance of premium and WTP for green products are the key and difficult points in promoting green products. The difference in the public’s WTP a price premium for green products under different influencing factors is not yet clear. This study explored the influence of public psychological factors and situational factors on the WTP a price premium for green products. The analysis in the current study showed that the initial model should be modified as shown in Fig. 2, and the following conclusions were drawn.

-

(1)

At present, the public’s WTP a price premium for green products was generally low. Only 30.1% of the respondents were WTP a price premium for green products. The vast majority of respondents were unwilling to pay price premiums for green products. It was difficult to improve the public’s acceptance of premiums for green products, which was the key and difficult point that the current society needs to pay attention to when promoting green products.

-

(2)

Functional value, conditional value, green value, price importance, and value-expressive influence all positively affected the public to pay a price premium for green products. The influencing factors from large to small were conditional value > green value > function value > value-expressive influence > price importance. Emotional value, price search tendency, normative influence, and informational influence had no significant influence on the WTP for green product premiums. The premium of green products can promote the public’s WTP more if it was identified as a green signal.

-

(3)

The public who were married, had master’s degree or above, and had working years of 1 year or less and whose disposable monthly income was above 50,000 yuan and whose occupations were engineering and technical personnel had the highest WTP a price premium for green products.

-

(4)

Situational factors (policy guidance and media promotion) played a moderating role. Policy guidance had a positive moderating effect on the relationship between emotional value, conditional value, green value, normative influence, value-expressive influence, and WTP a price premium for green products. Media publicity had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between functional value, emotional value, conditional value, green value, normative influence, and WTP a price premium for green products.

Policy implications

This research mainly proposes the policy implications of increasing the WTP a price premium for green product from the two perspectives of government and enterprises, as shown in Fig. 3.

Government level

-

(1)

Green value is an important driving force to enhance consumers’ premium payment. From the point of view of the government, it should play its exemplary and leading role; spread the value concept of green environmental protection to the public; enhance the people’s sense of gain, glory, and happiness in green consumption; and promote the joint governance of the environment by the whole people.

-

(2)

As a subdimension of price sensitivity, price importance significantly affects the WTP a price premium. The government should disclose reliable price data of green products and provide the public with feasible channels to fully understand green product price information. At the same time, the government should conduct reasonable supervision on the prices of green products all over the country, so as to prevent manufacturers from arbitrarily increasing prices when consumers do not know enough about green products.

-

(3)

This study confirms that policy guidance and media publicity have a positive moderating effect on the path of influencing factors on WTP a price premium for green products. The government should establish sound green laws and regulations, formulate strict green product access mechanisms, and strengthen supervision. At the same time, through the formulation and implementation of housing subsidies and tax reduction and exemption policies, it is possible to increase support for green product manufacturers and give appropriate preferential policies.

-

(4)

The government should make use of mass media to widely publicize the laws and regulations, product information, and policy welfare of green products, actively encourage and advocate the public to buy green products, and promote the transformation of people’s life to green. The government can convey the positive role of green products to the public through public opinion and environmental education, promote green products during festivals such as World Environment Day and World Water Day, and convey the concept of green consumption.

Enterprise level

-

(1)

Functional value is an important factor affecting the WTP a price premiums. The public can often recognize the green value of green products in terms of energy saving, consumption reduction, and environmental protection, but many consumers believe that the environmental value of consumption behaviors often comes at the expense of quality, price, or convenience. Therefore, enterprises need to improve the performance-price ratio of green products and improve the quality and performance of green products at the same price.

-

(2)

Economic factors are still the main obstacle to the public’s WTP a price premium for green products, with significant economic subsidy effect. This study proves that the WTP a price premium for green products is higher in the circumstance of subsidies, promotions, or discounts.

-

(3)

The study confirms that the form of value expression of the reference group will also significantly affect the WTP a price premium. The public’s purchasing behavior of green products will be constrained by the influence of social environment and surrounding groups as well as various social norms. Therefore, for enterprises, word-of-mouth marketing can be carried out to start the dissemination of green product information among relatives and friends, so as to establish the positive effect of green products, and the influence of products can also be expanded by inviting celebrities to endorse the products.

Public level

-

(1)

The value of green products is an important factor affecting the willingness to pay price premiums. The public needs to enhance their own awareness, understanding, and recognition of green products and realize the important role of green products in environmental protection, so as to improve their attitudes toward green products and practice green consumption behavior.

-

(2)

The reference group can influence the willingness to pay a price premium for the green products. The public can publicize their own green product purchase experience and drive and influence the people around them to buy green products through their own purchase behavior.

References

Abdullahv AM, Mohd RM, Mohd RB et al (2018) Intention and behavior towards green consumption among low-income households. J Environ Manag 227(1):73–86

Ali T, Onur BH (2020) The green consumption effect: how using green products improves consumption experience. J Consum Res 47(1):25–39

Atkinson L, Rosenthal S (2014) Signaling the green sell: the influence of eco-label source, argument specificity, and product involvement on consumer trust. J Advert 43(1):33–45

Audia PG, Rousseau H E , Brion S (2020) CEO power and nonconforming reference group selection. Organ Sci, in press.

Babutsidze Z, Chai A (2018) Look at me saving the planet! The imitation of visible green behavior and its impact on the climate value-action gap. Ecol Econ 146:290–303

Basuroy S, Desai KK, Talukdar D (2006) An empirical investigation of signaling in the motion picture industry. J Mark Res 43(2):287–295

Bearden WO, Netemeyer RG, Tell JE (1989) Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. J Consum Res 15:473–481

Bei LT, Simpson EM (1995) The determinants of consumers' purchase decisions for recycled products: an application of acquisition-transaction utility theory. Adv Consum Res 22(1):257–261

Berger J (2017) Are luxury brand labels and "green" labels costly signals of social status? an extended replication. PLoS One 12(2):e0170216

Bergh DD, Ketchen DJ, Orlandi JI et al (2018) Information asymmetry in management research: past accomplishments and future opportunities. J Manag 45(1):122–158

Biswas A, Roy M (2015) Leveraging factors for sustained green consumption behavior based on consumption value perceptions: testing the structural model. J Clean Prod 95:332–340

Chang TW, Chen YS, Yeh Y et al (2020) Sustainable consumption models for customers: investigating the significant antecedents of green purchase behavior from the perspective of information asymmetry. J Environ Plann Man 2:1–21

Chekima B, Wafa S, Igau OA et al (2016) Examining green consumerism motivational drivers: does premium price and demographics matter to green purchasing?.J Clean. Prod 112:3436–3450

Chen K, Peng Q (2014) Analysis on the influence of reference group on green consumption attitudinal-behavioral gap. China Popula Res Environ 24(S2):458–461

Cheung M, To WM (2019) An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers' green purchase behavior. J Retail Consum Serv 50:145–153

Childers TL, Rao AR (1992) The influence of familial and peer-based reference groups on consumer decisions. J Consum Res 19(2):198–211

Cicia G, Del Giudice T, Scarpa R (2002) Consumers’ perception of quality in organic food. Br Food J 104:200–213

Darby S (2006) Social learning and public policy: lessons from an energy-conscious village. Energy Policy 34(17):2929–2940

Delgado MS, Harriger JL, Khanna N (2015) The value of environmental status signaling. Ecol Econ 111:1–11

Drozdenko R, Jensen M, Coelho D (2011) Pricing of green products: premiums paid, consumer characteristics and incentives. Int J Bus Mar Deci Sci 4(1):106–116

Fang J, Wen ZL, Liang DM, Li NN (2015) Analysis of regulatory effects based on multiple regression. Psychol Sci 8(03):715–720

Gadenne D, Sharma B, Kerr D, Smith T (2011) The influence of consumers' environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviors. Energy Policy 39(12):7684–7694

Ge WD, Sheng GH, Gong SY (2020) Formation mechanism of consumers' willingness to co-create green value -- from the perspective of attribution theory and reciprocity theory. Soft Sci 01: 13 to 18.

Ghosh PK, Manna AK, Dey JK, Kar S (2021) Supply chain coordination model for green product with different payment strategies: a game theoretic approach. J Clean Prod 290(2):125734

Goncalves HM, Lourenco TF, Silva GM (2016) Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: a fuzzy-set approach. J Bus Res 69(4):1484–1491

Griskevicius V, Tybur JM, Den Bergh BV (2010) Going green to be seen: status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J Pers Soc Psychol 98(3):392–404

Guo YL, Zhang P, Liao J, Wu F et al (2020) S Social exclusion and green consumption: a costly signaling approach. Front Psychol 11:535489

Gupta AK (2021) Innovation dimensions and firm performance synergy in the emerging market: a perspective from dynamic capability theory & signaling theory. Technol Soc 64:101512

Gupta S, Ogden DT (2009) To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. J Consum Mark 26(6):376–391

Hahnel U, Oliver A, Michael W et al (2015) The power of putting a label on it: green labels weigh heavier than contradicting product information for consumers' purchase decisions and post-purchase behavior. Front Psychol 6:1392

Jia H, Wang YG, Liu JY et al (2008) A review of research on the influence of reference groups on consumption decision-making. Fore Eco Manag 30(6):51–58

Jie F, Sheng GH, Gong SY (2019) Study on the influence of reference groups on green consumption behavior of Chinese residents under the background of civil environmental co-governance. China Pop Resour Environ 29(8):66–75

Joshi Y, Rahman Z (2015) Factors affecting green purchase behavior and future research directions. Int Strateg Manag Rev 3(1–2):128–143

Khan SN, Mohsin M (2017) The power of emotional value: exploring the effects of values on green product consumer choice behavior. J Clean Prod 150:65–74

Kilbourne W, Pickett G (2008) How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J Bus Res 61(9):885–893

Kollmuss A, Agyeman J (2002) Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ Educ Res 8:239–260

Laroche M, Bergeron J, Barbaroforleo G (2013) Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J Consum Mark 18(6):503–520(18)

Li Q, Long R, Chen H (2017) Empirical study of the willingness of consumers to purchase low-carbon products by considering carbon labels: a case study. J Clean Prod 161:1237–1250

Lichtenstein DR, Ridgway NM, Netemeyer RG (1993) Price perceptions and consumer shopping behavior: a field study. J Mark Res 30(2):234–245

Lin PC, Huang YH (2012) The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J Clean Prod 22(1):11–18

Lin ST, Niu HJ (2018) Green consumption: environmental knowledge, environmental consciousness, social norms, and purchasing behaviour. Bus Strateg Environ:1–10

Moloney S, Strengers Y (2014) 'Going green'?: the limitations of behaviour change programmes as a policy response to escalating resource consumption. Environ Policy Gov 24(2):94–107

Niemeyer S (2010) Consumer voices: adoption of residential energy-efficient practices. Int J Consum Stud 34(2):140–145

Ogiemwonyi O, Harun AB, Alam MN et al (2020) Do we care about going green? Measuring the effect of green environmental awareness, green product value and environmental attitude on green culture. An insight from Nigeria. Environ Cli Tec 24(1):254–274

Ohtomo S, Hirose Y (2007) The dual-process of reactive and intentional decision making involved in eco-friendly behavior. J Environ Psychol 27(2):117e125

Park CW, Lessig VP (1977) Students and housewives: differences in susceptibility to reference group influence. J Consum Res 4(2):102–110

Peattie K (2010) Green consumption: behavior and norms. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. Annual Rev 35:195–228

Priest SH (2009) Risk communication for nanobiotechnology: to whom, about what, and why? J Law Med Ethics 37(4):759–769

Rao AR, Monroe KB (1988) The moderating effect of prior knowledge on cue utilization in product evaluations. J Consum Res 15(2):253–264

Ren Y, Luo S, Fan B et al (2020) The role of green consumption in promoting high-quality development. China Environ Manag 12(01):24–30

Rousseau S, Vranken L (2013) Green market expansion by reducing information asymmetries: evidence for labeled organic food products. Food Policy 40:31–43

Ruey-Jer BJ, Daekwan K, Kevin ZZ, et al (2021) E-platform use and exporting in the context of Alibaba: a signaling theory perspective. J Int Bus Stud, in press.

Sana SS (2020) Price competition between green and non-green products under corporate social responsible firm. J Retail Consum Serv 55:102118

Scheel C, Eduardo A, Bello B (2020) Decoupling economic development from the consumption of finite resources using circular economy. A model for developing countries. Sustainability 12(4):1291

Schuitema G, Groot J (2015) Green consumerism: the influence of product attributes and values on purchasing intentions. J Consum Behav 14(1):57–69

Sheng GH, Yue BB, Xie F (2019) Research on the driving mechanism of Chinese residents' green consumption behavior from the perspective of environmental co-governance. Sta. Infor. Forum 34(01):109–116

Sheth JN, Newman BI, Gross BL (1991) Why we buy what we buy: a theory of consumption values. J Bus Res 22(2):159–170

Sinha I, Batra R (1999) The effect of consumer price consciousness on private label purchase. Int J Re Mark 16(3):237–251

Sparks P, Shepherd R (1992) Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior - assessing the role of identification with green consumerism. Soc Psychol Q 55(4):388–399

Spence M (1978) Job market signaling. Q J Econ 87(6):335–374

Spence M (2002) Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. Ameri Eco Rev 92(3):434–459

Suki NM (2016) Consumer environmental concern and green product purchase in Malaysia: structural effects of consumption values. J Clean Prod 132:204–214

Sun Y, Wang S, Gao L, Li J (2018) Unearthing the effects of personality traits on consumer’s attitude and intention to buy green products. Nat Hazards 93(1):299–314

Thaler RH, Sunstein CR (2009) Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin, Yale University Press

Wang P, Liu Q, Qi Y (2014) Factors influencing sustainable consumption behaviors: a survey of the rural residents in China. J Clean Prod 63:152–165

Wang DH, Yao T, Yao F (2015) To buy or not to buy——a study on the purchase intention of ecological products from the perspective of contradictory attitudes. Nankai Manag Rev 18(2)

Wang DH, Duan S, Zhang C et al (2018) Research on repeated purchase intention of green products——based on the moderating effect of the public notification method. Soft Sci 032(002):134–138

Welsch H, Kühling J (2009) Determinants of pro-environmental consumption: the role of reference groups and routine behavior. Ecol Econ 69(1):166–176

Whitehead M (2000) Willingness to pay. The Lancet 356(9227):437

Wu B (2014) A review of research on green consumption. For Ecol Manag 36(11):178–189

Yadav R, Pathak GS (2017) Determinants of consumers' green purchase behavior in a developing nation: applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol Econ 134:114–122

Young W, Hwang K, Mc Donald S et al (2010) Sustainable consumption: green consumer behavior when purchasing products. Sustain Dev 18(1):20–31

Yu S, Lee J (2019) The effects of consumers' perceived values on an intention to purchase upcycled products. Sustainability 11(4):1034

Yu CL, Zhu XD, Wang X et al (2019) Face consciousness and purchase intention of green products -- moderating effect of use situation and relative price level. Manag Rev 31(11):139–146

Yun W, Hanson N (2020) Weathering consumer pricing sensitivity: the importance of customer contact and personalized services in the financial services industry. J Retail Consum Serv 55:102085

Zhang L (2018) Research on the impact of green product logos and packaging environmental protection attributes on consumers' willingness to purchase green products. Doctoral

Zhang JY, Du QL (2009) Reference groups, cognitive styles and consumers' purchase decisions—a review from the perspective of behavioral economics. Econ Perspect 11:83–86

Zhang L, Li D, Cao C, Huang S (2018) The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: the mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. J Clean Prod 187:740–750

Zhang Y, Xiao C, Zhou G (2019) Willingness to pay a price premium for energy-saving appliances: role of perceived value and energy efficiency labeling. J Clean Prod 242:118555

Zong JC, Lv Y, Tang FF (2014) Environmental attitudes, willingness to pay and product environmental premium-evidence from laboratory research. Nanki Manag Rev 17(2):153–160

Amna Kirmani, (1997) Advertising Repetition as a Signal of Quality: If It's Advertised So Much, Something Must Be Wrong. Journal of Advertising 26 (3):77-86

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by: the Major Project of the National Social Science Funding of China (19ZDA107); the Key Project of the National Social Science Funding of China (18AZD014); the Major Project of the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (2018SJZDA008); the Think Tank of Green Safety Management and Policy Science (2018 “Double First-Class” Initiative Project for Cultural Evolution and Creation of CUMT 2018WHCC03); the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX20_2028); and the Future Scientists Program of China University of Mining and Technology (2020WLKXJ034).

Availability of data and materials

Data can be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Menghua Yang: Methodology; software; formal analysis; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Hong Chen: Conceptualization; visualization; supervision; funding acquisition. Ruyin Long: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; visualization; funding acquisition. Yujie Wang: Software; writing—review and editing. Congmei Hou: Software; writing—review and editing. Bei Liu: Writing—review and editing; visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Baojing Gu

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, M., Chen, H., Long, R. et al. Will the public pay for green products? Based on analysis of the influencing factors for Chinese’s public willingness to pay a price premium for green products. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28, 61408–61422 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14885-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14885-4