Abstract

Seeds, young plants and adult plants of the perennial Mediterranean leguminous shrub Dorycnium pentaphyllum Scop. were exposed to Cd (1–100 μM) or Zn (10–10,000 μM) on nutrient solution. This species is resistant to Cd and Zn at different phenological stages. The lowest doses of Zn and Cd improved seed germination and young seedling growth, while only the highest doses of both heavy metals inhibited germination and decreased growth. High doses of Cd reduced seed imbibition and young seedling water content, while Zn did not. Osmotic adjustment was more efficient in Zn-treated young plants than in Cd-treated ones, while chlorophyll concentrations decreased in the former but not in the latter. Those differences were not observed anymore in adult plants. Exclusion processes were more efficient at the adult stage than at the young seedling stage and were more marked in response to Zn than to Cd. It is concluded that D. pentaphyllum could be used for phytostabilization of heavy metal-contaminated areas. The physiological strategies of tolerance, however, differ according to the age of the plants and the nature of the metal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The accumulation of toxic metals such as cadmium (Cd) and zinc (Zn) as a result of anthropogenic activities poses an important risk to many environments. The incidence of heavy metal pollution associated with mining activities has been widely studied (Del Río et al. 2002; Wong 2003; Vogel-Mikuš et al. 2005). The dispersion of those contaminants, their accumulation in the soil and their inclusion in the trophic cycle represent a fundamental risk for human health. Technologies currently available for the remediation of metal-contaminated soils are expensive, time-consuming and may produce secondary waste (Fitz and Wenzel 2002). Phytoremediation consists in the use of green plants to clean up contaminated sites (Pilon-Smits 2005). The exploitation of so-called hyperaccumulating plants that are capable to accumulate more than 1% Zn or 0.1% Cd on a dry matter basis may somewhat contribute to the removal of contaminants from the soil (Robinson et al. 1998). Several higher plant species developed strategies for heavy metal resistance enabling them to survive in highly metal- contaminated sites, but only a few of them are real metal hyperaccumulators. Moreover, hyperaccumulators usually exhibit a low biomass production and accumulate one single toxic element, while several pollutants are most of the time simultaneously present in the contaminated area (Wong 2003; Pilon-Smits 2005).

Considering the huge number of contaminated sites throughout the world, there is an urgent need to stabilize polluted lands in order to prevent bulk erosion, reduce air-borne transport and leaching of pollutants. Perennial plants able to grow on ultramafic soils (Léon et al. 2005) or to spontaneously colonize degraded lands (Del Río et al. 2002; Lutts et al. 2004) may then be used for phytostabilization purposes, even if they do not accumulate heavy metals in the shoots. Plants suitable for phytostabilization should express constitutive resistance at all developmental stages, from the germination to the adult phase. This is particularly important in the year of establishment when young plants are still vulnerable. It is, therefore, surprising that studies dealing with the physiological basis of heavy metal resistance most usually consider plant material at a single developmental stage, although it has been demonstrated for other environmental constraints that the physiology of stress resistance varies according to the phenological evolution of the plant (Lutts et al. 1995; Munns 2005).

Dorycnium pentaphyllum Scop. is a perennial leguminous shrub well-adapted to xeric habitats in the Mediterranean regions (Caravaca et al. 2003). The presence of this species was recently reported on a former mining area (Lefèvre 2007). At the adult stage, the plant produces high amounts of biomass, a highly ramified shoot and a deep root system. It is, therefore, tempting to speculate that this species may be of special interest for phytostabilization. Major problems, however, may occur as a result of slow emergence and low relative growth rate at the seedling stage, which appear to be characteristics of several species of the genus Dorycnium (Douglas and Foote 1994; Dear et al. 2003; Bell 2005). Hence, it is of crucial importance to determine the impact of heavy metals on germination and seedling development and to compare the physiological behavior of young plants, with the ability of adult plants to cope with high external doses of heavy metals. The tested hypothesis was that the response of D. pentaphyllum to heavy metal stress varies during vegetative growth and that such evolution could be different for different heavy metals. Experiments were performed using seeds collected on a contaminated area from the Southeast of Spain with an objective to answer the following questions: (1) is D. pentaphyllum able to resist high doses of Cd and Zn at three distinct growth stages (germination, young plants and adult plants)? and (2) is the resistance of D. pentaphyllum associated with tolerance mechanisms allowing the plant to cope with high amounts of accumulated toxic ions or with exclusion mechanisms enabling the plant to avoid the accumulation of pollutants in the shoot tissues?

Materials and methods

Site description and plant material

Mature seeds were collected in October 2000 from Dorycnium pentaphyllum Scop. plants growing spontaneously on a heavy metal-contaminated site at the Sierra Minera of Cartagena (“La Peña”; 37°37′20″ N, 0°50′55″W) in the Southeast of Spain. The soil texture was 22.1% sand, 55.4% fine and coarse silt and 22.5% clay. Its organic matter content was 1.7%; pH-H2O and pH-KCl were 6.7 and 6.2, respectively. The nutrient and heavy metals contents were as follow: (in mg 100 g−1 dry weight) 480 Ca, 12 K, 3 Na, 38 Mg and 1 P, and (in mg kg−1 dry weight) 3965 Zn, 12.5 Cr, 6.8 Ni, 65 Cu, 12.7 Cd and 5671 Pb. Seeds collected from 20 different plants were pooled.

Experiment 1: seed germination

Seeds were surface-disinfested for one min in 70% ethanol and incubated in sterile half-strength Hoagland solution in the absence (control) or presence of 10, 100 or 1,000 μM Cd (supplied as CdCl2; Sigma Chemical, Belgium) or 100, 1,000 or 10,000 μM Zn (supplied as ZnSO4 · 7H2O; Sigma Chemical). Seeds were maintained in Petri dishes (20 seeds per Petri dish and 5 Petri dishes per treatment) on two Whatman 41 filter papers moistened with 7 ml solution in a growth chamber under a 12 h photoperiod (150 μmol m−2 s−1 PFD) at a constant temperature of 25°C. Seeds were incubated for 3 weeks; the number of germinated seeds was recorded daily, considering radicle protrusion as a germination criterion. Kinetics of imbibition was recorded during the first 3 days of incubation; seeds were weighed at the time of the onset of experiment and after 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. Each time before weighing, germinated seeds were surface-dried with sterile filter paper. The relative increase in seed fresh weight was calculated using the formula as follow: L i = [(W f − W i)/W i] × 100 where L i is the level of imbibition (in %), W i is the initial weight of seeds and W f their weight at time f.

The number of intact seedlings was quantified at the end of the stress treatment considering that an intact seedling presents a morphologically normal radicle and unfolded cotyledons. A seed was considered to show abnormal germination if shoot growth occurred in the absence of radicle extension.

After 3 weeks, the obtained intact seedlings were carefully removed from the filter paper, separated from the remaining part of the seeds, rinsed for 30 s in distilled water and gently blotted dry. The length of the young root system and young shoot was measured. Those parts were then separated and weighed to determine their mean fresh weight. After incubation for 72 h in an oven at 70°C, the dry weight was recorded and Cd and Zn concentrations were determined in these tissues as stated below.

Seeds which failed to germinate in the presence of Cd or Zn were thoroughly rinsed three times (10 min each) in sterile deionized water to remove all adhering heavy metals and then incubated in new Petri dishes in the absence of heavy metals under similar environmental conditions as described above. The recovery percentages were determined by the following formula: a/(c − b) × 100 where a is the total number of seeds germinated after transfer to the control conditions, b is the total number of seeds germinated in stress conditions, and c is the total initial number of seeds sown.

Experiment 2: young plant stage

Seeds were germinated in 10 plastic jars (3 l) filled with a substrate of silt-clay-loam and sand (1:2:1:2); the jars were incubated in a growth chamber under a 12 h photoperiod (110 μmol m−2 s−1 PFD provided by Sylvania fluorescent tubes (F36 W/133-T8/CW) at a day/night temperature of 28/20°C. Substrate and young plants were sprayed daily for few minutes with sterile deionized water. Each jar contained 50 seeds. Young seedlings of uniform size (5 cm; 7–9 leaves stage) were then individually transferred to tanks containing 1.1 l of the following nutrient solution: (in mM) 5.0 KNO3, 1.0 NH4H2PO4, 0.5 MgSO4, 5.5 Ca(NO3)2 and (in μM) 25 KCl, 10 H3BO3, 1.0 MnSO4, 1.0 ZnSO4, 0.25 CuSO4, 10 Na2MoO4 and 160 Fe-EDDHA. The pH was adjusted to 6.0 and was checked and readjusted daily throughout the experiment. Solutions were permanently aerated under a stream of air at the bottom of each tank and kept at a constant O2 concentration of 7.5 mg l−1 measured with a dissolved oxygen probe (CellOx 325; WTW, Weilheim, Germany) and a precision instrument (ProfiLine Dissolved Oxygen Meter Oxi 197-S; WTW, Weilheim, Germany). Young plants were fixed on polystyrene plates floating on the solution. Tanks were randomly arranged in a phytotron under a 12 h photoperiod at a temperature of 25°C during the day and 20°C during the night and a relative humidity of 70%. Light was provided by Phillips HPLR 400 W lamps at a mean PAR of 320 μmol m−2 s−1. After 1 week of acclimation in the absence of heavy metals, plants were exposed to 0 (control), 1, 10 or 100 μM Cd or to 10, 100 or 1,000 μM Zn. Solutions were renewed at an interval of 3 days, and tanks were randomly rearranged in the phytotron.

A total number of 420 plants were used. Plants were randomly harvested prior to application of the stress treatment (day 0) and after 10, 15, 18, and 21 days and used for ion and chlorophyll quantification and water status determination as described below. During the time-course of the experiment, the height of the shoot, the length of the main roots, the number of leaves on the main stem, the number and the mean length of the ramification stems and the mean number of leaves on these ramifications were quantified on all living plants at an interval of 3 days.

Experiment 3: adult stage

Seeds were allowed to germinate as described above for Exp 2. One month after germination, plants were transferred to pots (one plant per pot) containing 3 l of a soil substrate (18.8% silt, 37.3% clay and 42.1% sand) under natural light supplemented by Phillips lamps (G/93/2; 400 W) providing a minimal PFD of 175 μmol m−2 s−1, a temperature of 25 ± 2°C and a relative humidity of 70%. Each month, the plants were fertilized with 0.4% Algoflash (NPK 4-6-8).

After 15 months, 45 adult plants were acclimated in a hydroponic system using NFT (Nutrient Film Technique). They were carefully removed from the soil, roots were rinsed under gentle agitation in deionized water and placed in perforated pots (5 l) containing Grodan rockwool as a mechanical support. Nutrient solution was similar to the solution used in Exp 2. The shoots were then cut back to 15 cm. Three groups of 15 plants were placed on hydroponic tables (3 m × 2.5 m) with a slope of 1.5%. A 50 l tank was used for supplying nutrient solution. Continuous circulation was maintained at a flow of 10 l min−1. The solution was changed every week till the final harvest.

After transfer to the NFT system, all plants were maintained for 4 weeks on control nutrient solution similar to the solution used in Exp 2. At the end of this acclimation period, the top of each stem (including ramification stems) was indexed by white ink (Tippex). One group of 15 plants was then exposed to 10 μM CdCl2, a second group to 100 μM ZnSO4 · 7H2O and a third group was kept as the control. Plants were exposed to these treatments for a period of 14 weeks under a 16 h photoperiod (mean PAR of 300 μmol m−2 s−1; Philips HPLN 400 W) and 70% relative humidity. Temperature was 35°C during the day and 20°C during the night. Elongation rate was recorded separately on the main stem and ramification stem and defined as the increase in the length of the corresponding organs occurring during the total period of exposure to the stress. The height of the shoot, the number and the mean length of the ramification stems were recorded on all plants each week.

For each treatment, five plants were harvested after 8, 11, and 14 weeks and used for ion and chlorophyll quantification and water status determination. Ion concentrations were recorded for leaves and stems separately at the basal level (BL) referring to organs already present at the time of stress application and at the upper level (UL) resulting from the elongation process occurring during the time-course of stress exposure.

Ion and pigment quantifications

For each treatment and each type of organ, three samples (50 mg DW) were digested in 35% HNO3 and evaporated to dryness on a sand bath at 80°C. Minerals were then dissolved in 0.1 N HCl, and Cd or Zn concentrations were determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Varian SpectrAA-300; Varian, Inc., CA, USA).

Chlorophyll and carotenoid concentrations were recorded on five leaves per plant and five plants per treatment considering leaves at similar positions for the different plants. The mean sample corresponding to pooled leaves was ground in 4 ml 80% cold acetone. After filtration and centrifugation at 10,400×g for 10 min at 4°C, the absorbance of the extract was measured at 645 and 663 nm by a Beckman DU640 (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, USA) spectrophotometer. Chlorophyll (Chl) a and b and carotenoid concentrations were estimated according to Lichtenthaler (1987).

Water status

Shoot water potential (Ψ w) and osmotic potential were determined between 12:00 and 14:00 h. Shoot water potential (Ψ w) was evaluated immediately after sampling by the pressure chamber method (PMS Instrument Co., Orlando, USA) using the main stem and three ramifications on each plant. For determination of osmotic potential (Ψ s), tissues were quickly collected, cut into small segments, placed in Eppendorf tubes perforated with four small holes and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. After being encased individually in a second intact Eppendorf tube, they were allowed to thaw for 30 min and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 15 min at 4°C. The collected tissue sap was analyzed for Ψ s estimation. Osmolarity (c) was assessed with a vapour pressure osmometer (Wescor 5500; Wescor, Inc., UT, USA) and converted from mosmoles kg−1 to MPa using the formula as follows: Ψ s (MPa) = −c (mosmoles kg−1) × 2.58 × 10−3 according to the Van’t Hoff equation.

Statistical analysis

Stat View 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis of all parameters. Percent germination data and water content were transformed into arc sine square roots before statistical analysis to ensure homogeneity of error variance. The metal concentrations in plant tissues were log-transformed to normalize the frequency distribution. Discontinuous variables were transformed by the square formula [y = (x + 3.8)0.5], according to De Munter (1958). If the F value indicated significant differences (P ≤ 0.05), mean differences were compared according to Scheffé F test for growth parameters and according to Waller–Duncan k ratio t test for metal concentration.

Results

Experiment 1: seed germination

Germination started after 3 days in seeds maintained in control conditions and a mean maximal germination percentage of 79.3% was recorded after 10 days (Fig. 1). The lowest concentrations of Zn (100 and 1,000 μM) had no impact on the kinetics of germination, while the highest one (10,000 μM) slightly delayed germination and significantly reduced the final germination percentage recorded after 17 days (P ≤ 0.01; Fig. 1a). A similar trend was recorded for Cd treatment except that the lowest concentration (10 μM) slightly stimulated germination as shown by an unexpected increase in the final germination percentage (P ≤ 0.05; Fig. 1b). In contrast, 100 μM CdCl2 delayed seed germination, but did not affect the final germination percentage; however, Cd at the highest dose (1,000 μM) drastically inhibited seed germination that hardly exceeded 40% after 17 days (Fig. 1b).

Time-course changes in seed germination of Dorycnium pentaphyllum exposed to increasing doses of Zn (a) or Cd (b). Seeds were exposed for 17 days to half-strength Hoagland solution (control) supplemented with 100, 1,000 or 10,000 μM Zn or 10, 100, 1,000 μM Cd. * = significantly different from the control at P ≤ 0.05

Imbibition of seeds during the first 72 h was not affected by Zn treatment, even at the highest dose, while both 100 and 1,000 μM Cd reduced it (Table 1). Fresh weights of young roots and shoots obtained from germinated seeds were reduced only in response to 10,000 μM Zn and 1,000 μM Cd, as it was the case for root and shoot length (Table 1). Dry weights were also reduced in response to those treatments, but to a lesser extent than fresh weight as a consequence of a decrease in water content (data not shown). The abnormal germination percentage increased in response to 1,000 and 10,000 μM Zn as well as in response to 1,000 μM Cd, but remained always lower than 10%. Zn accumulation (Fig. 2a) in young roots and shoots obtained from seeds germinated in the presence of Zn was proportional to the external Zn dose and was always higher in roots than in shoots (P ≤ 0.01). Cd was undetectable in control seedlings and remained low in shoots in response to 10 μM Cd. In contrast, Cd accumulated to similar extent in both types of organs in response to 100 and 1,000 μM Cd (Fig. 2b).

Zn and Cd accumulation in roots and shoots of young seedlings of Dorycnium pentaphyllum obtained from seeds germinating in the presence of increasing doses of Zn (a) or Cd (b). Seeds were exposed to half-strength Hoagland solution (control) supplemented with 100, 1,000 or 10,000 μM Zn or 10, 100, 1,000 μM Cd for 3 weeks. Means with common letters are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Waller–Duncan k ratio t test. ND not detected

Seeds that failed to germinate in Zn-enriched solution were still unable to germinate in control conditions; after rinsing in deionized water, less than 5% of the seeds previously exposed to the highest dose of Zn recovered (data not shown). In contrast, Cd-induced inhibition of germination was clearly reversible since ungerminated rinsed seeds were able to germinate after Cd removal.

Experiment 2: young plant stage

Mortality of young plants exposed to the highest dose of Cd (100 μM) and Zn (1,000 μM) did not exceed 10%. The lowest dose of Cd slightly increased both stem and root length (P ≤ 0.05), but had no impact on the mean number of nodes, the mean number of ramifications and the mean length of the ramification stems (Table 2). Cd at high doses (10 and 100 μM) inhibited stem elongation, mainly through a decrease in the internode length. Cd at 10 and 100 μM also decreased the elongation of ramification stems (P ≤ 0.05), but this effect was relatively lower than the deleterious impact of Cd on the main stem elongation (P ≤ 0.001). Stem elongation also increased in response to the lowest dose of Zn, but root elongation remained mostly unaffected. The mean number of ramification increased in response to 10 and 100 μM Zn and was unaffected by the highest dose of Zn. The mean length of ramification stem was similar to the control at 10 μM Zn, but was significantly reduced at higher doses.

The lowest dose of Cd (1 μM) slightly increased the shoot dry weight (Table 3; P ≤ 0.05). Dry weights of both roots and shoots remained unaffected after 3 weeks of exposure to 10 μM Cd (Table 3). Cd at 100 μM induced a decrease in the shoot and root dry weight (Table 3). After 3 weeks of exposure to 100 μM Cd, the shoot/root ratio estimated on a dry weight basis decreased by more than 20% as compared to controls. Mean water content remained unaffected in plants exposed to 1 or 10 μM Cd, while it decreased in plants exposed to 100 μM Cd.

The lowest dose of Zn (10 μM) significantly increased the root dry weight, but had no impact on the shoot dry weight. Both root and shoot dry weights decreased in response to the highest dose of Zn (Table 3). Zn had no impact on the root and shoot water content, irrespective of the dose or the duration of exposure.

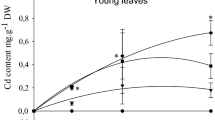

Zn concentration increased with time at the root level (Fig. 3a), whereas it increased until day 10 and then remained constant until the end of the experiment at the shoot level. A similar trend was recorded for Cd. Plants exposed to 1 and 10 μM Cd exhibited a decrease in the shoot water potential occurring concomitantly with a decrease in the leaf osmotic potential (Table 4). Although Ψ s still decreased in 100 μM Cd-treated plants, the shoot water potential remained similar to controls after 3 weeks of treatment. The decrease in both Ψ w and Ψ s values was more pronounced in Zn- than in Cd-treated plants. In contrast to Cd, Zn clearly reduced the concentration in all quantified photosynthetic pigments and Chl a/Chl b ratio increased in response to the highest dose of Zn.

Time-course changes in Zn (a, b) and Cd (c, d) concentrations in roots (a, c) and shoots (b, d) of young plants of Dorycnium pentaphyllum exposed to Zn (10, 100 and 1,000 μM) or Cd (1, 10 and 100 μM) for 3 weeks. Since Cd concentration remained below the detection limit in control plants, it is not indicated. Means with common letters are not significantly different at P ≤ 0.05, according to Waller–Duncan k ratio t test

Experiment 3: adult plants

All the tested plants remained alive during the time-course of the experiment, and the presence of heavy metals had no impact on the mean shoot weight (fresh weight: 51.6 ± 4.3 g per plant; dry weight: 14.7 ± 2.1 g per plant). Elongation of the main stem (Table 5) was not affected by the presence of heavy metals; however, the mean elongation of ramification stems decreased in response to Zn treatment. In contrast, Zn significantly increased the number of ramification after 14 weeks’ treatment.

Zinc accumulation (Fig. 4) occurred to a similar extent in stems and leaves at both basal (BL) and upper (UL) levels. Its accumulation, however, remained significantly lower in adult plants than in young plants (Expt 2). In contrast to Zn, Cd concentration (Fig. 4) was clearly higher in stems than in leaves and was also higher in organs at BL than at UL, thus suggesting that this toxic heavy metal may be excluded from the elongating plant parts. Cd accumulation slightly increased in the UL part and decreased in the BL part during the time of stress exposure.

Time-course changes in Zn (a, b) and Cd (c) concentrations and water potential of shoots (d) of Dorycnium pentaphyllum exposed to 100 μM Zn (a, b), 10 μM Cd (c) and 10 μM Cd or 100 μM Zn (d), respectively. Heavy metal concentrations were recorded separately at the basal (BL represents organs already present at the time of stress application) and upper (UL represents organs resulting from the elongation process occurring during the time-course of stress exposure) levels. Means with common letters are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05), according to Waller–Duncan k ratio t test (heavy metal concentration) or Scheffé F test (water potential)

Mean shoot Ψ w (Fig. 4) was the lowest in Zn-treated plants and intermediate in Cd-treated ones; in both cases Ψ w still decreased until the end of the experiment. As far as osmotic potential is concerned, Ψ s values remained constant for both BL and UL of control plants (Table 6). The leaf Ψ s remained similar for BL and UL in Cd-treated plants, while the leaf Ψ s was lower at BL than at UL of Zn-treated plants (P ≤ 0.05). For all the considered treatments, leaf Ψ s was lower in adult plants than in young plants exposed to similar doses (Exp 2). Photosynthetic pigment concentrations (Table 6) were lower at BL than at UL, including control plants. The presence of heavy metals decreased Chl b at both BL and UL, but decreased Chl a at BL only. Carotenoid concentrations were not affected at all in Cd- and Zn-treated plants.

Discussion

Species belonging to the genus Dorycnium are perennial legumes that have the ability to adapt to low fertility soils and low rainfall conditions. In cold semiarid Mediterranean conditions, those plants are suitable for revegetation purposes and soil reclamation (Walker et al. 2003; Alegre et al. 2004; Bell 2005; Bell et al. 2007). The presence of high concentrations of heavy metals in former mining areas often constitutes a serious threat for ecosystem stability (Del Río et al. 2002; Wong 2003; Walker et al. 2003; Vogel-Mikuš et al. 2005). The present study demonstrates that D. pentaphyllum, a shrub species well-adapted to dry environments, could be a promising species for revegetation and phytostabilization of Cd- and Zn-contaminated areas because this plant species appears to be highly resistant to both heavy metals at different phenological stages from germination to adult stage. According to Dixit et al. (2001), a concentration of 4 μM of Cd in the soil solution may be considered as relevant of highly contaminated substrates. While growth inhibition and extensive senescing symptoms occur in the model plant species Arabidopsis thaliana exposed for a few days to 10 μM Cd (Larsson et al. 2002), we demonstrated that D. pentaphyllum was able to germinate in the presence of 100 μM Cd and that young and adult plants exposed to 10 μM Cd were still able to survive and to grow without exhibiting any senescing symptoms. Similarly, more than 90% of the young plants exposed to 1,000 μM Zn were still surviving after 3 weeks of treatment.

The ability of seeds to germinate in the presence of heavy metals is of primary concern for rehabilitation of degraded lands. Seeds produced by adult plants growing on contaminated areas may accumulate high concentrations of heavy metals, which may hamper further germination steps, even if germination occurs in the absence of the pollutant (Léon et al. 2005; Regvar et al. 2006; Vogel-Mikuš et al. 2007). Although the endogenous concentrations of Cd and Zn were not checked in seeds used for the present work, it should be noted that seeds were collected from a heavy metal-contaminated area and they exhibited a normal behavior in control conditions, with a final germination percentage of nearly 80%. It is noteworthy that the lowest Cd dose accelerated and even slightly increased germination. Cheng and Zhou (2002) reported a similar observation in wheat, but the underlying physiological reason for such an improvement still remains unknown. Kopyra and Gwozdz (2003) recently demonstrated that nitric oxide, which may be overproduced in response to heavy metals, could be involved in the hastening of germination through the stimulation of enzyme activities involved in the management of oxidative stress. At the highest doses, both Cd and Zn inhibited germination. Such an inhibition may be the consequence of Cd interaction with calmodulin (Rivetta et al. 1997), inhibition of reserve mobilization through a decrease in α-amylase activities (Atici et al. 2003; Li et al. 2005) or interference with the hormonal status of the germinating seeds (Atici et al. 2003, 2005; Sharma and Kumar 2002). The present work also shows that Cd and Zn have contrasting effects on seed imbibition. Zn did not compromise imbibition, and it may thus be inferred that Zn-induced inhibition of germination may occur later, as compared to that of Cd, at a time when germination is no longer reversible, thus explaining the basis for irreversible inhibition of the germination process in Zn-treated seeds. In contrast, imbibition was strongly reduced in response to 100 and 1,000 μM Cd, which may lead to a reversible inhibition of the germination process.

Low Cd doses not only improved germination but also growth of young plants. Similar observations have been reported for various plant species (Küpper et al. 2001; Sandalio et al. 2001). Sobkowiak and Deckert (2003) reported that such stimulation could not be attributed to an impact of Cd on genes involved in the control of the cell cycle. We also showed that Zn might also stimulate stem, but not root elongation. Some authors consider that plant species, which preferentially occupy Zn-polluted areas, possess numerous physiological strategies leading to the restriction of Zn absorption and/or its vacuolar or apoplasmic sequestration. In control conditions, those mechanisms may reduce Zn availability in tissues, and as a result Zn requirement for normal metabolism could be high in those species (Shen et al. 1997), thus explaining a positive impact of low-Zn external doses.

Ontogeny may influence the response of the plant in terms of not only growth but also accumulation and distribution of toxic ions. Germination has been reported to be rather resistant to heavy metal stress when compared to latter developmental stages (Li et al. 2005; An et al. 2004). So far as D. pentaphyllum is concerned, this could be related to the low levels of heavy metals accumulated in germinating seeds as compared to what was recorded in young plants. It might be expected that a seed germinating in a closed Petri dish under saturating atmospheric humidity accumulates lower amounts of heavy metals than young plants presenting a transpiration stream. As far as adult plants were concerned, Cd concentration in the shoot was of the same order of magnitude than in young plants, while Zn concentration in the shoots drastically decreased by more than 70%, suggesting that an exclusion process may operate in adult plants and that it is more efficient for Zn than Cd. The distribution of heavy metals between the root and the shoot systems also varies according to the developmental stage. In young seedlings, Zn was mainly restricted to the radicle, while Cd exhibited an even distribution between radicle and shoots. Young plants displayed a different pattern; Cd concentration in the roots being more than five times higher than in shoots. Differences in heavy metal partitioning between roots and shoots may be due to the timing of endoderm differentiation as well as the mean distance between root tip and endoderm appearance (Lux et al. 2004). Phloem retranslocation may also occur at different rates for Zn and Cd (Cakmak et al. 2000). Zn redistribution among organs of different ages varies with the age of the plant (Herren and Feller 1996). It is clearly more efficient and occur faster than for Cd (Page and Feller 2005), thus explaining the uneven distribution of Cd within the shoots of adult plants.

The physiological consequences of accumulated heavy metals may also vary according to the developmental stage. Although Zn and Cd share numerous physical and chemical properties and are also very often simultaneously present in heavy metal-contaminated mining areas, their impact on stressed-plant properties were quite different, especially at the juvenile stage. Cd stress had a strong deleterious impact on the tissue water content, while Zn had no such detrimental effects. Water stress is a well-known secondary constraint resulting from Cd toxicity that interferes with Ca channels at the guard cell level impairing stomatal regulation (Perfus-Barbeoch et al. 2002). Moreover, Hollenbach et al. (1997) reported a Cd-induced increase in abscisic acid concentration, which may contribute to reducing the stomatal conductance. The stress-induced decrease in water potential could be considered as an attempt to cope with secondary-induced water stress. The accumulation of osmo-compatible solutes in response to heavy metals has been frequently reported (Schat et al. 1997). Our data suggest that this osmotic adjustment was more efficient in response to Zn than in response to Cd in young plants. Abilities of plants to reduce Ψ s were higher in adult than in young plants, but a higher impact of Zn on osmotic adjustment was not valid anymore at this developmental stage. The presence of heavy metals in tissues should not be regarded as the only factor inducing osmotic adjustment because a difference was recorded for Ψ s values between BL and UL of Zn-treated plants when Zn was uniformly distributed. In contrast, Ψ s values were similar for both levels of Cd-treated plants, although this pollutant accumulated to a higher extent in the basal part of the shoots.

Differences between Cd and Zn impact on young plants were also recorded for photosynthetic pigment concentrations. It has been reported that Cd induces modifications in the chloroplast ultrastructure and chlorophyll biosynthesis (Di Cagno et al. 2001). We show that, at least at the young plant stage, Zn is even more detrimental to chlorophyll concentration than Cd, but this could be explained, at least partly, by higher accumulations of Zn in tissues rather than by a specific resistance of the photosynthetic pigments to Cd. In contrast, no significant differences were recorded between Zn and Cd for pigment concentrations in adult plants; both heavy metals reduced chlorophyll concentrations to a similar extent. Carotenoids play a key role in the protection of photosystem II against oxidative damages. Although their concentrations were reduced in young stressed plants, especially in response to Zn, they remain unaffected in response to heavy metals in adult plants.

D. pentaphyllum is a valuable plant species for the rehabilitation of semi-arid degraded lands (Alegre et al. 2004). The present work shows that this plant could also be used as an attractive tool for the revegetation of heavy metal-contaminated areas since it appears to be resistant at different developmental stages of plant growth. The physiological strategies employed by the plant to cope with external toxic ions somewhat vary according to the specific developmental stage. Further works are necessary to identify the mechanisms of tolerance at the young plant stage as well as the strategies of stress avoidance in adult plants.

Abbreviations

- BL:

-

Basal level

- Chl:

-

Chlorophyll

- EDDHA:

-

Ethylenediamine-di(o-hydroxy)-phenylacetic acid

- Exp:

-

Experiment

- L i :

-

Level of imbibition

- NFT:

-

Nutrient film technique

- PAR:

-

Photosynthetically active radiation

- PFD:

-

Photon flux density

- Ψ s :

-

Osmotic potential

- Ψ w :

-

Water potential

- UL:

-

Upper level

References

Alegre J, Alonso-Blázquez N, de Andrés EF, Tenorio JL, Ayerbe L (2004) Revegetation and reclamation of soils using wild leguminous shrubs in cold semiarid Mediterranean conditions: literfall and carbon and nitrogen returns under two aridity regimes. Plant Soil 263:203–212

An YJ, Kim YM, Kwon TI, Jeong SW (2004) Combined effect of copper, cadmium, and lead upon Cucumis sativus growth and bioaccumulation. Sci Total Environ 326:85–93

Atici O, Agar G, Battal P (2003) Interaction between endogenous plant hormones and alpha-amylase in germinating chickpea seeds under cadmium exposure. Fresenius Environ Bull 12:781–785

Atici O, Agar G, Battal P (2005) Changes in phytohormone contents in chickpea seeds germinating under lead or zinc stress. Biol Plant 49:215–222

Bell LW (2005) Relative growth rate, resource allocation and root morphology in the perennial legumes, Medicago sativa, Dorycnium rectum and D. hirsutum grown under controlled conditions. Plant Soil 270:199–211

Bell LW, Bennett RG, Ryan MH, Moore GA, Ewing MA, Bennett SJ (2007) Establishment and summer survival of the perennial legumes Dorycnium hirsutum and D. rectum in Mediterranean environments. Aust J Exp Agr 45:1245–1254

Cakmak I, Welch RM, Hart J, Norvell WA, Oztrük L, Kochian LV (2000) Uptake and retranslocation of leaf-applied Cd109 in diploid, tetraploid and hexaploid wheats. J Exp Bot 51:221–226

Caravaca F, Alguacil MD, Diaz G, Roldan A (2003) Use of nitrate reductase activity for assessing effectiveness of mycorrhizal symbiosis in Dorycnium pentaphyllum under induced water deficit. Comm Soil Sci Plant Anal 34:2291–2302

Cheng Y, Zhou QX (2002) Ecological toxicity of reactive X-3B red dye and cadmium acting on wheat (Triticum aestivum). J Environ Sci China 14:136–140

De Munter P (1958) Sur les transformations des variables aléatoires. Bull Soc Belgium Stat 3:97–111

Dear BS, Moore GA, Hughes SJ (2003) Adaptation and potential contribution of temperate perennial legumes to the southern Australian wheatbelt: a review. Aust J Exp Agr 43:1–18

Del Río M, Font R, Almela C, Velez D, Montoro R, De Haro A (2002) Heavy metals and arsenic uptake by wild vegetation in the Guadiamar river area after the toxic spill of the Aznalcóllar mine. J Biotechnol 98:125–137

Di Cagno R, Guidi L, De Gra L, Soldatini GF (2001) Combined cadmium and ozone treatments affects photosynthesis and ascorbate-dependent defences in sunflower. New Phytol 151:627–636

Dixit V, Pandey V, Shyam R (2001) Differential antioxidative responses to cadmium in roots and leaves of pea (Pisum sativum L. cv. Azad). J Exp Bot 52:1101–1109

Douglas GB, Foote AG (1994) Establishment of perennial species useful for soil conservation and as forages. N Z J Agr Res 37:1–9

Fitz WJ, Wenzel WW (2002) Arsenic transformations in the soil-rhizosphere-plant system: fundamentals and potential application to phytoremediation. J Biotechnol 99:259–278

Herren T, Feller U (1996) Effect of locally increased zinc contents on zinc transport from the flag leaf lamina to the maturing grains of wheat. J Plant Nutr 19:379–387

Hollenbach B, Schreiber L, Hartung W, Dietz KJ (1997) Cadmium leads to stimulated expression of the lipid transfer protein genes in barley: implications for the involvement of lipid transfer proteins in wax assembly. Planta 203:9–19

Kopyra M, Gwozdz EA (2003) Nitric oxide stimulates seed germination and counteracts the inhibitory effect of heavy metals and salinity on root growth of Lupinus luteus. Plant Physiol Biochem 41:1011–1017

Küpper H, Lombi E, Zhao FJ, Wieshammer G, McGrath SP (2001) Cellular compartmentation of nickel in the hyperaccumulators Alyssum lesbiacum, Alyssum bertolonii and Thlaspi goesingense. J Exp Bot 365:2291–2300

Larsson EH, Asp H, Bornman JF (2002) Influence of prior Cd2+ exposure on the uptake of Cd2+ and other elements in the phytochelatin-deficient mutant cad1-3, of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot 368:447–453

Lefèvre I (2007) Investigation of three Mediterranean plant species suspected to accumulate and tolerate high cadmium and zinc levels. Morphological, physiological and biochemical characterization under controlled conditions. Ph.D. Dissertation, Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve

Léon V, Rabier J, Notonier R, Barthélémy R, Moreau X, Bouraïma-Madjébi S, Viano J, Pineau R (2005) Effects of three nickel salts on germinating seeds of Grevillea exul var. rubiginosa, an endemic serpentine proteacea. Ann Bot 95:609–618

Li WQ, Khan MA, Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y (2005) Effects of heavy metals on seed germination and early seedling growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Growth Regul 44:645–650

Lichtenthaler HK (1987) Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol 148:350–382

Lutts S, Kinet JM, Bouharmont J (1995) Changes in plant response to NaCl during development of rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties differing in salinity resistance. J Exp Bot 46:1843–1852

Lutts S, Lefèvre I, Delpérée C, Kivits S, Dechamps C, Robledo A, Correal E (2004) Heavy metal accumulation by the halophyte species Mediterranean saltbush. J Environ Qual 33:1271–1279

Lux A, Šottníková A, Opatrná J, Greger M (2004) Differences in structure of adventitious roots in Salix clones with contrasting characteristics of cadmium accumulation and sensitivity. Physiol Plant 120:537–545

Munns R (2005) Genes and salt tolerance: bringing them together. New Phytol 167:645–663

Page V, Feller U (2005) Selective transport of zinc, manganese, nickel, cobalt and cadmium in the root system and transfer to the leaves in young wheat plants. Ann Bot 96:425–434

Perfus-Barbeoch L, Leonhardt N, Vavasseur A, Forestier C (2002) Heavy metal toxicity: cadmium permeates through calcium channels and disturbs the plants water status. Plant J 32:539–548

Pilon-Smits E (2005) Phytoremediation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 56:15–39

Regvar M, Vogel-Mikuš K, Kugonič N, Turk B, Batic F (2006) Vegetational and mycorrhizal successions at a metal polluted site: indications for the direction of phytostabilisation? Environ Pollut 144:976–984

Rivetta A, Negrini N, Cocucci M (1997) Involvement of Ca2+-calmodulin in Cd2+ toxicity during the early phases of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seed germination. Plant Cell Environ 20:600–608

Robinson BH, Leblanc M, Petit D, Brooks RR, Kirkman JH, Gregg PEH (1998) The potential of Thlaspi caerulescens for phytoremediation of contaminated soils. Plant Soil 203:47–56

Sandalio LM, Dalurzo HC, Gomez M, Romero-Puertas MC, del Rio LA (2001) Cadmium-induced changes in the growth and oxidative metabolism of pea plants. J Exp Bot 364:2115–2126

Schat H, Sharma SS, Vooijs R (1997) Heavy metal-induced accumulation of free proline in a metal-tolerant and a nontolerant ecotype of Silene vulgaris. Physiol Plant 101:477–482

Sharma SS, Kumar V (2002) Responses of wild type and abscisic acid mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana to cadmium. J Plant Physiol 159:1323–1327

Shen ZG, Zhao FJ, McGrath SP (1997) Uptake and transport of zinc in the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens and the non-hyperaccumulator Thlaspi ochroleucum. Plant Cell Environ 20:898–906

Sobkowiak R, Deckert J (2003) Cadmium-induced changes in growth and cell cycle gene expression in suspension-culture cells of soybean. Plant Physiol Biochem 41:767–772

Vogel-Mikuš K, Drobne D, Regvar M (2005) Zn, Cd and Pb accumulation and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation of pennycress Thlaspi praecox Wulf. (Brassicaceae) from the vicinity of a lead mine and smelter in Slovenia. Environ Pollut 133:233–242

Vogel-Mikuš K, Pongrac P, Kump P, Nečemer N, Simčič N, Pelicon P, Budnar M, Povh B, Regvar M (2007) Localisation and quantification of elements within seeds of Cd/Zn hyperaccumulator Thlaspi praecox by micro-PIXE. Environ Pollut 147:50–59

Walker DJ, Clemente R, Roig A, Bernal MP (2003) The effects of soil amendment on heavy metal bioavailability in two contaminated Mediterranean soils. Environ Pollut 122:303–312

Wong M (2003) Ecological restoration of mine degraded soils, with emphasis on metal contaminated soils. Chemosphere 50:775–780

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS-Belgium, convention n° 2.4565.02). The authors are also very grateful to Mrs Anne Iserentant for her precious help in cadmium quantification, to Mrs Brigitte Van Pee and Mr. Baudouin Capelle for germination test and plant culture and to Mr Antonio Robledo Miras for his help in collecting the seeds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lefèvre, I., Marchal, G., Corréal, E. et al. Variation in response to heavy metals during vegetative growth in Dorycnium pentaphyllum Scop.. Plant Growth Regul 59, 1–11 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-009-9382-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-009-9382-z