Abstract

Fulfilling consumer expectations of corporate social responsibility (CSR) can bring strategic advantage to firms. However, research on the topic is fragmented across disparate disciplines, and a comprehensive framework to connect CSR supply and demand is missing. As a result, firms often supply CSR that does not attract demand, as signified by pessimism about ethical consumerism in recent years and the inconclusive link between corporate financial and social performance. In this study, we propose a framework of strategic CSR management to define how a company’s supply of CSR could meet consumer demand for ethical products by aligning managerial and consumer perspectives. We then investigate empirically whether such a strategic approach, which integrates potential demand in CSR management, would influence consumer choice of products with CSR components. Our hybrid choice modeling allows the inclusion of psychological biases caused by social desirability and cynicism to increase result validity. The findings support the explanatory power of the framework and reveal that consumers prefer some CSR elements while others adversely affect choices. This study advances the understanding of strategic CSR management and its impact on consumer choice and helps managers include the right mix of CSR characteristics in their products to satisfy ethical consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Business has widely adopted corporate social responsibility (CSR) over the past two decades, and attention has shifted from merely engaging in scattered CSR activities to identifying a strategic role for CSR in business (McWilliams et al. 2006; Porter and Kramer 2006). The theory-of-the-firm perspective on CSR (McWilliams and Siegel 2001) implies that CSR could be an integral part of differentiation strategies either directly through product features or indirectly through reputation and brand image. However, research into strategic CSR is still in its early stage and lacks a comprehensive framework to integrate CSR actions into corporate strategies (McWilliams et al. 2006; Rogers 2013). For example, in a survey of more than 55 000 consumers across the 15 largest markets in 2013, the Reputation Institute found that CSR suppliers commonly suffer from problems, such as irrelevance of CSR initiatives to consumers and other stakeholders and a poor fit of CSR activities with core business (Rogers 2013).

The supply and demand theory of CSR (Anderson and Frankle 1980; Aupperle et al. 1985; McWilliams and Siegel 2001) suggests that, to maximize profits, firms should only supply CSR that consumers, and other stakeholders, demand. However, a framework that illustrates how CSR supply could match such demand is still missing. In the fields of marketing and consumer behavior, there are occasional studies on how consumers respond to CSR practices, but they address only a few aspects of CSR actions without integrative thinking and with little connection to firms’ CSR management processes (Beckmann 2007; Crane 2008; Öberseder et al. 2013). Sen and Bhattacharya (2001) provided a model of factors specific to companies and consumers that moderate consumer response to CSR initiatives. However, their contingent factors lack systematic selection criteria, and the conceptual framework leans toward a consumer perspective (consumer evaluations of the company and its product offerings) not linked to a managerial approach.

In this study, we aim to address three gaps that are important in understanding the relationship between CSR supply and demand. First, a model to define and characterize CSR supply aimed at the ethical consumer market is missing. A few studies have attempted to integrate CSR into the strategic management process by identifying the modes and stages of integration (e.g., Galbreath 2006; Mirvis and Googins 2006; Sharp and Zaidman 2010; Vitolla et al. 2017). However, previous research has not connected stages of strategic management with specifying CSR supply. Second, while general propositions on value sharing between business and society (Chandler 2015; Porter and Kramer 2011) or consumers and corporations (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001) exist, it is unclear how the concepts apply to strategic CSR management. CSR supply and demand theory does not provide guidance on how the two can meet in the ethical market. Subsequently, firms often supply CSR that does not match demand and becomes irrelevant to consumers, as signified by pessimism of ethical consumerism due to the limited popularity of ethical brands (Irwin 2015) and the somewhat positive, but inconclusive, link between corporate social and financial performance (Barnett and Salomon 2012; Peloza 2009; Wang et al. 2016). Third, there has been little empirical research on which CSR characteristics consumers would truly value to create an impact on purchase behavior. Connolly and Shaw (2006) argued that ethical products on the market do not respond to consumer concerns, a problem worsened by the latent nature of consumer demand for CSR that causes consumer inability to specify the characteristics of CSR they desire (Devinney et al. 2006; Kotler 1973). Unsystematic thinking of those characteristics in CSR management further exacerbates the issue. These shortcomings have contributed to a poor understanding of why the supply of ethical products and services does not attract consumer attention.

Thus, it is critical in the field of business ethics to understand how well strategic CSR management can match CSR supply with its true consumer demand and to what extent strategic CSR management may inspire consumer purchasing. This addresses two important questions. First, we propose a framework for strategic CSR management to explain how a firm’s supply of CSR could approximate consumer demand for ethical products and services. The conceptual framework addresses the first two gaps identified. It defines CSR supply for the ethical market in strategic terms and typifies potential CSR components in three stages: CSR strategy formulation, implementation, and evaluation. Furthermore, it aligns both managerial and consumer perspectives to allow CSR supply and demand to match through consumer/supplier interactions and achieve the desired value sharing.

We then investigate empirically whether, and to what extent, the strategic CSR approach will influence consumer choice for ethical products using a hybrid choice model. We test the explanatory power of the framework on consumer choice and identify specific CSR characteristics that influence consumer decisions; this addresses the third gap identified above. Hybrid choice modeling focuses on true preferences to define consumers’ genuine rather than biased demand for CSR. Compared to traditional survey techniques, this method enables enhanced realism by incorporating the impact of key attitudinal bias on response behavior. To our knowledge, this is the first time hybrid choice modeling is introduced in the field of ethical consumerism. Theoretically, our findings contribute to the knowledge of effective CSR supply that can match actual and potential consumer CSR demand and address a disciplinary divide between consumer and organizational research (Crane 2008). Practitioners can use our analysis to develop CSR strategies and initiatives that match consumer concerns and create a competitive advantage for a responsible company.

This study has four parts. First, we develop a conceptual framework of CSR management process by synthesizing existing literature in consumer behavior, marketing, and strategic CSR management. We proceed by introducing the hybrid choice model to empirically test our framework, and link the choice survey design to the conceptual framework. Drawing on a sample of 308 potential tourists (2464 choices) in the United Kingdom (UK), our findings suggest how and when responsibility can influence consumer choice and fulfill its strategic promise. Finally, we discuss our contribution to consumer-oriented CSR knowledge and managerial practice and conclude with suggestions for further research in this domain.

Matching CSR Supply with Demand: An Integrative Framework for Strategic CSR Management

In this section, we outline a conceptual framework for strategic CSR management to illustrate how a firm’s supply of CSR, defined through a CSR management process, can meet consumer demand. To do this, we synthesize categories and characteristics of responsibility that may influence consumer choice. The framework aligns managerial and consumer perspectives on CSR based on the general principle of shared value between business and society suggested by Porter and Kramer (2006, 2011). The idea of shared value is that the relationship between business and society is interdependent, as a successful business needs a healthy society and vice versa. Since business success relies heavily on consumers, strategic decisions must include their values, preferences, and expectations.

Strategic CSR is defined as “any ‘responsible’ activity that allows a firm to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage, regardless of motive” (McWilliams and Siegel 2010, p. 1480). The primary objective of strategic CSR is to gain an advantage on the ethical market by focusing mainly on consumers. Therefore, strategic CSR management must be an interactive process between management and consumers to ensure positive consumer reaction. We call this an integrative approach, as consumer perspectives are incorporated in the CSR management process. The concept of CSR-induced consumer–company congruence (“C–C congruence,” Sen and Bhattacharya 2001) explains the need to align manager and consumer perspectives in strategic CSR management. Sen and Bhattacharya defined C–C congruence as compatibility between consumers and companies’ key characters; based on congruence, consumers may associate with a company and satisfy their self-definitional needs. C–C congruence is a vital component linking CSR initiatives and consumer evaluation of a company and its products, and research has supported its role in developing loyalty or purchase intention (Deng and Xu 2017; Lee et al. 2012; Martinez and; del Bosque 2013; Park et al. 2017).

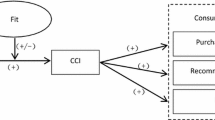

In our integrative framework of strategic CSR management (Fig. 1), the concept of C–C congruence links company supply of CSR with consumer demand for it. As in ordinary strategic management, a strategic CSR management process has three components: strategy formulation, implementation, and evaluation. Because consumer demand for CSR arises from preferences, expectations, and lifestyles (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), each component consists of one or several categories that are further divided into characteristics that represent details of CSR that consumers might demand. Research supports a link between CSR or an ethical business approach and favorable consumer outcomes, such as customer loyalty, perceived brand equity, and purchase intention (Deng and Xu 2017; Iglesias et al. 2018, 2019; Inoue et al. 2017; Lombart and Louis 2014; Mohr and Webb 2005). However, consumer demand for CSR is predominantly latent, as consumers are often unaware of the details of their demand until they encounter a matching product offering and the demand is actualized (Devinney et al. 2006; Kotler 1973). Thus, consumer responses to CSR initiatives are only a reflection of their demand for CSR, and companies need to supply CSR in a way that connects them with the customers to realize potential gains (Lee et al. 2012). Once the characteristics of CSR offered correspond to consumer demand, C–C congruence forms an interactional channel to match supply with demand and convert consumer demand for unspecified ethical business behavior into actual demand for CSR. Through this interaction, strategic CSR management can alter consumer purchase behavior.

CSR Strategy Formulation

CSR strategy formulation is the choice of specific CSR strategies from a range of possible options. It must reflect consumers’ CSR values, preferences, and expectations to have appeal and engage the interactional channel of C–C congruence. A firm can analyze consumer concerns related to CSR through various means, including market surveys, formal and informal consultations, and dialogue with customers. In the framework, we focus on three key issues in a firm’s CSR strategy formulation: (1) whether a firm’s CSR value orientations echo consumer values and concerns, (2) how the stakeholder interests that a firm prioritizes relate to consumer interests, and (3) whether a firm is genuine and competent in its CSR initiatives. In our conceptual framework, these concerns are categorized as CSR policy orientations, stakeholder emphasis, and fit with business.

CSR policy orientation refers to what specific purpose and responsibility a CSR strategy pursues. Three generic CSR domains underpin CSR policy orientations: philanthropy, ethics, and environmental sustainability. These three orientations originate from two widely used CSR models: the CSR pyramid (Carroll 1991) and the triple bottom line (TBL, Elkington 1997). Carroll (1991) presented four levels of responsibility: economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic. We exclude economic and legal responsibilities based on the strong argument that CSR exceeds the usual business and legal requirements of company operations (Baron 2009). The remaining ethical and philanthropic responsibilities are complemented by environmental sustainability from the TBL, a model that forms the basis for formal CSR reporting (GRI 2016). The other components of the TBL are excluded, as one focuses on economic performance while the other, social aspect, overlaps with ethical and philanthropic orientation.

In our conceptual framework, strategic CSR management is only workable if a firm’s CSR policy orientation is consonant with consumers’ CSR values and primary concerns. This link follows social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986), according to which people tend to adopt the identity of the group they belong to or are categorized in. Products with specific ethical values and CSR features connect the customers buying the products with the company that supplies them. Choosing ethical products from a specific company implies that customers endorse the company’s CSR policy orientation and identify with them (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Choi and Ng 2011; Deng and Xu 2017; Marin et al. 2009). This is, in a sense, an ‘in-group’ identification in social identity theory.

Empirical studies demonstrate that consumers are, in general, supportive of the three CSR domains/orientations. For example, consumers usually prefer ethics and philanthropy (Auger et al. 2008; de los Salmones et al. 2005; see also; Peloza and Shang 2011 for a summary of studies), and environmental actions are repeatedly highlighted as a preference (Mohr and Webb 2005; Öberseder et al. 2013; Orazi and Chan 2018). We will later test which of the three CSR policy orientation(s) consumers favor.

Stakeholder emphasis is a firm’s intention to attach importance and prioritize its responsibility to meet key stakeholder groups’ CSR expectations. Theory of stakeholder salience suggests that a firm normally perceives stakeholder salience based on power, legitimacy, and urgency of each stakeholder group. These refer to their power to influence the firm, the legitimacy of the stakeholders’ relationships with the firm, and the urgency of the stakeholders’ claim on the firm (Mitchell et al. 1997). However, in strategic CSR management, how a firm considers stakeholders must be linked with consumers’ CSR interests. Consumers expect a balanced treatment of stakeholders (Öberseder et al. 2013), but this balance does not necessarily refer to equal amounts of attention to each stakeholder and may differ considerably from the company’s perspective.

Based on classifications by Clarkson (1995) and Wheeler and Sillanpaa (1997), a firm’s primary stakeholders may include shareholders/investors, employees, customers, suppliers, local communities, and the natural environment. Consumers may have their preferred stakeholder emphases, as the interests of certain stakeholders may be more connected with their interests. Suppliers, as a stakeholder group, align with the firm (Seal 2013); if consumers care about a firm’s CSR, they will monitor the social responsibilities of the firm’s suppliers. Consumers themselves are a stakeholder group that companies may emphasize, and companies can require consumers to share some responsibilities to promote comprehensive responsibility. Vitell (2015) called this consumer social responsibility (CnSR). We selected four, external stakeholder groups that may interest consumers: suppliers, customers, local communities, and the natural environment. We excluded employees as an internal stakeholder group because standard CSR initiatives for this group, such as health care benefits or training, are nearly indistinguishable from common employee incentives. Shareholders are excluded because they are the beneficiaries of successful strategic CSR due to its instrumental nature.

In CSR strategy formulation, the concept of fit with business derives from the concept of strategic fit in management. Strategic fit means that a firm must have the actual resources and capabilities to support the strategy (Grant 2007). A firm’s competitive advantage lies in a unique combination of its resources and capabilities, as maintained in the resource-based view of the firm (Barney 1991). The fit of CSR strategy with business implies that a firm’s strategic CSR plan is determined by its core competencies and organizational capacity and its ability to excel in its efforts (Rangan et al. 2012). CSR fit with business is not just important for integrating CSR strategy into a firm’s business strategy, but also for creating positive impressions that the firm’s CSR initiatives are competent and genuine.

Theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957) explains the importance of fit with business from a consumer perspective. According to this theory, a person whose private beliefs or behaviors do not align with public actions experiences cognitive dissonance. With CSR, dissonance leads to avoidance or change of behaviors to reduce the feeling of discomfort (Reilly et al., 2017). For consumers, supporting companies with ill-fitting CSR strategy might create cognitive dissonance, as it implies that they do not care about actions under the responsibility banner. Therefore, CSR fit with business creates a perception of comfort for consumers, and they avoid dissonance. Despite a general agreement on the importance of CSR fit (Deng and Xu 2017; Peloza and Shang 2011), fit may be irrelevant to consumer choice (Lafferty 2007) and low-fit cause-related marketing may benefit a company (Fatma and Rahman 2016; Nan and Heo 2007). High-fit but profit-oriented CSR initiatives might also cause negative consumer outcomes (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006). Following these examples, we differentiate between general CSR initiatives (low-fit) and those connected to a firm’s core business (high-fit) to investigate consumer attitude toward these CSR characteristics.

CSR Strategy Implementation

After CSR strategy formulation, the second stage of strategic CSR management focuses on how to execute a CSR strategy. We synthesize four typical action styles from the literature (John and Thomson 2003; Wartick and Cochran 1985; Van Tulder and Van der Zwart 2006): proactive, reactive, inactive, and counteractive. Proactive CSR indicates a firm’s commitment to social good that exceeds legal compliance and minimum stakeholder expectations (McWilliams et al. 2006). When implementing CSR strategies, the firm would anticipate any potential CSR problems caused by its business operations and make efforts to prevent problems. Reactive CSR shows that firms only become involved in CSR to meet laws and regulations (Maignan and Ferrell 2001; Sethi 1975), act in response to stakeholder pressure or unexpected events (Groza et al. 2011), or mitigate damage and protect their image after the fact (Murray and Vogel 1997; Wagner et al. 2009). Inactive style means that firms may either do nothing, do the minimum beyond their economic and legal responsibility, or focus on costs and business efficiency when performing CSR (Van Tulder and Van der Zwart 2006). Such firms are passive, reluctant, or defensive in acting for broader social responsibility, following Friedman’s theorem that the only corporate social responsibility is to increase profits. The counteractive style indicates that firms use strategies and methods to oppose, neutralize, or mitigate any damaging effect of criticisms directed at them. It can be aggressive (such as using financial advantage, public relations staff or threats) to counter critics and maintain public legitimacy. It could also be less aggressive by attempting to de-escalate or neutralize hostile activists by resolving conflict sources thereby silencing opposition. At the macro scale, firms may act politically to influence the social environment and shift outcomes to their advantage (John and Thomson 2003; Scherer et al. 2014).

We suggest that the various styles of action differently affect consumers’ recognition and appreciation of CSR. Recognition is based on consumer knowledge of the company and its CSR activities and thus links with the concept of corporate cognitive associations in marketing literature (Brown and Dacin 1997). These include associations to both corporate ability and corporate social responsibility. Positive CSR associations can enhance corporate and product evaluations, whereas negative associations may have a detrimental effect. Therefore, consumer recognition of CSR actions is an important strategic goal. Proactive CSR initiatives may induce positive recognition and increase consumer purchase intention (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Groza et al. 2011; Kim 2017). Different action styles may also affect consumers’ appreciation of a firm’s CSR initiatives due to causal attributions linked with those styles. According to attribution theory, people tend to derive causal explanations for events even when none exist (Heider 1958). Subsequently, consumers make causal inferences to explain why firms engage in CSR (Ellen et al. 2006; Vlachos et al. 2009; Skarmeas and Leonidou 2013). Proactive actions can lead to positive attributions of underlying motives, as consumers believe proactive CSR initiatives are more genuine and value-driven (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Yoon et al. 2006). Reactive CSR actions impact consumers negatively due to the unfavorable connotation linked with reaction (Lee et al. 2009), and passive style weakens purchase intention (Kim 2017). However, research incorporating all four action styles is missing.

CSR Strategy Evaluation

CSR strategy evaluation is the stage for a firm to assess its CSR strategy performance and change or adjust its actions accordingly. From a consumer perspective, CSR strategy evaluation is the demonstration of CSR commitment. Consumers are interested in whether promised goals were reached and trustworthy evidence supports claims made. The evidence may be based on internal sources, such as corporate reports, or rely on external bodies, such as third-party verification. Consumers’ perception of the message credibility and its sources affects consumer response toward the firm and its products (Connors et al. 2017; Webb and Mohr 1998).

Zucker defined trust as “a set of expectations shared by all those involved in an exchange” (1986, p. 2). Corporate CSR commitment is crucial for creating consumer trust and it is a critical mediator between CSR supply and product choice or customer loyalty (Diallo and Lambey-Checchin 2017; Iglesias et al. 2018; Lombart and Louis 2014; Martinez and; del Bosque 2013; Park et al. 2017). Clear, honest, and effective communication of CSR performance plays a vital role in building trust between firms and consumers (Connors et al. 2017; Illia et al. 2013). Consumers may regard unsubstantiated or contested CSR claims as greenwashing or mere public relations, and this creates a threat to credible CSR and reduces potential business benefits (Orazi and Chan 2018; Nyilasy et al. 2013; Parguel et al. 2011). Therefore, we will compare the impact of internal and external evidence in establishing consumer trust.

Above, we have constructed the conceptual framework of strategic CSR management with three key components of CSR management process: CSR strategy formulation, CSR strategy implementation, and CSR strategy evaluation. We suggest that such a framework, grounded in the integration of both managerial and consumer perspectives, should have significant impact on consumer choice of ethical products. The validity of this claim needs to be tested in practice. Hence, the second part of this study is an empirical investigation to understand whether and to what extent the strategic CSR framework can influence consumer choice. We expect the impact of CSR characteristics on consumers to vary. In the following section, we explain the method of hybrid choice modeling we used to test the conceptual framework. We also discuss why the method is preferable to traditional survey methods in the pursuit of genuine ethical consumer preferences, particularly in overcoming inflated or insincere consumer intentions.

Methodology

Modeling Attitudes and Genuine Consumer Demand for CSR

Discrete choice analysis (McFadden 1974) enables dissecting the value a consumer draws from a product into its attributes (product features). In this sense, it is similar to the hedonic analysis proposed in conjunction with strategic CSR (McWilliams and Siegel 2010). However, while hedonic analysis investigates existing products on the market with a top-down approach, discrete choice analysis focuses on individual consumers and allows analysis of potential but non-existing product attributes.

Hybrid choice models (HCM; Walker and Ben-Akiva 2002) are an extension of the standard discrete choice models. They offer the potential to include psychological variables as latent constructs to explain choices. The key advantage of using an HCM over a standard choice model is the possibility to model unobserved preference heterogeneity (anticipated with ethical choice) and, subsequently, improved realism to model human behavior (Abou-Zeid and Ben-Akiva 2014). In this research, we incorporated SD and cynicism biases as latent attitudes in a hybrid choice model to analyze the impact of CSR categories and characteristics on consumer choice. From a model specification perspective, we did not expect the two biases to contribute directly to choice, but only when interacting with CSR characteristics that potentially induce bias. This approach is the equivalent of a behavioral mixture model with moderation (Abou-Zeid and Ben-Akiva 2014; Zanoli et al. 2015).

Quantitative methods to measure purchase intention dominate consumer-oriented CSR research, though they have been criticized for overestimating the influence of responsibility on consumer behavior (Auger and Devinney 2007; Beckmann 2007; Peloza and Shang 2011). For example, Devinney et al. (2006, p. 2) asked whether we are “as individuals as noble as we say in the polls,” suggesting that CSR survey results could be biased and might not reflect actual behavior. Since CSR is largely perceived as the ethical thing to do, a social desirability (SD) bias can lead survey respondents to favor responsible characteristics without respective actions in real life, creating a gap between stated intentions and real actions (Fernandes and Randall 1992; Podsakoff et al. 2003). Interviews could increase response validity (Beckmann 2007) but the latent nature of consumer demand for CSR hinders their use. According to the definition of latent demand (Kotler 1973), consumers themselves do not know the characteristics of their demand, and subsequently, they would not be able to describe them were open-ended questions asked. This calls for incorporating SD bias in quantitative analysis.

Cynicism is acknowledged to pose a severe problem to creating positive consumer responses through CSR (Mohr et al. 1998; Vallaster et al. 2012). Due to high-profile social and environmental scandals, consumers may demonstrate cynicism toward the concept of CSR as they perceive it to be dishonest or insincere behavior. Some forms of cynicism may impact both stated intentions and real actions identically, but a CSR survey with a strong ethical focus is likely to prompt a cynicism bias due to a transient mood state (Podsakoff et al. 2003), a reaction to a stimulus that reminds the respondents of scandals linked with corporate irresponsibility and greenwashing. Such a respondent is likely to engage in subversive cynicism (Odou and de Pechpeyrou 2011), or express a complaint that does not lead to action by stating an unfavorable intention (Chylinski and Chu 2010). Under these circumstances, cynicism bias can negatively moderate responses to a survey without a corresponding effect on real actions.

As noted by Roberts et al. (2018, p. 301), “existing empirical applications of HCMs tend not to be based in clear theoretical frameworks and thus it is often difficult to interpret the results.” Our application of HCM breaks this trend and its limitation. We based our model (Fig. 2) on the conceptual framework developed earlier (Fig. 1) and empirically tested the significance of the theoretical CSR categories and characteristics on consumer choice. We further incorporated key biases using a hybrid approach and added to the previously scarce use of choice modeling in the field (see Auger et al. 2008). We evaluated the ability of our model to explain overall consumer choice based on the likelihood ratio, and the significance of each CSR characteristic in contributing to choices based on robust t-statistics (Train 2009). Including the five CSR categories synthesized in Fig. 1 implies an overall hypothesis that all significantly explains choice or induces bias, because non-significant attributes must be already excluded during survey design (Hensher et al. 2015; Train 2009). However, the CSR categories represent a general level of CSR impact on choice. Development of specific hypotheses or propositions related to the CSR characteristics within the five categories was deemed impossible due to the latent nature of consumer demand for CSR—consumers themselves are not able to identify CSR characteristics that influence their choices without first encountering them. Thus, previous research offers little support to formulate such hypothetical details. Instead, the CSR characteristics synthesized under the five categories of strategic CSR management in our conceptual framework were tested empirically for significance of choice without specific propositions, following common practice in choice modeling. Using the terminology in the domain, Fig. 2 depicts the categories and characteristics of CSR as CSR attributes and attribute levels. We discuss their development in detail in the next section.

Survey Instrument and Experimental Design

In a choice study, respondents are offered scenarios that present choice tasks. Choice is the only variable provided by the respondent; independent variables (attributes of choice) are defined during the survey design. Leisure travel is an example of discretionary spending that permits the study of ethical perspectives and CSR influence on related choices, as all basic requirements of living have been addressed before such travel is considered. Therefore, we established a holiday trip hotel choice as our study scenario. The choice task presented two alternatives described by product attributes (‘Hotel 1,’ ‘Hotel 2’) and a no-choice alternative (‘Some other hotel’); the nature of CSR as a new product aspect led to including a minimum number of alternatives. The alternatives were not labeled as fictitious brands to avoid distracting respondents (Hensher et al. 2015). We excluded a case where a hotel would demonstrate no responsibility, as some level of CSR must exist to map consumer demand for it. Furthermore, a CSR-free, ‘irresponsible’ hotel option could have signaled this as a pro-CSR opinion poll, affecting respondent choices. A respondent preferring no CSR activity could have selected the no-choice alternative to indicate a preference against responsibility without explicit expression of such preference.

Our D-efficient experimental design (Hensher et al. 2015) consisted of 24 choice tasks divided into three blocks to reduce respondent fatigue. As a result, each respondent faced eight choice tasks. The experiment also randomized the order in which the eight tasks within a block were shown to respondents to minimize the risk of bias from a learning effect. The design was generated using Ngene software, and estimators from a pilot study were used as design priors for the attributes and attribute levels. As the pilot study results lacked any significant interactions among attributes, a main-effects-only design was selected. The survey instrument was in three sections: choice survey, attitudinal indicator questions, and sociodemographic questions. Next, we will discuss the choice and attitude sections in detail.

Choice Tasks

A choice task presents alternatives, from which respondents choose, using attributes and attribute levels to represent the elements of a product expected to impact choice. We included eight attributes and two to four levels of each attribute in the scenarios. Three of the attributes were common criteria for holiday hotel choices in this context: distance to beach, location relative to a town, and price, and they were defined based on preparatory interviews with experts in the travel industry. Earlier application of discrete choice modeling to consumer ethics supports the use of such reference attributes (Auger et al. 2008). Five attributes focused on the CSR aspects that we expected to influence consumer choice based on our theoretical framework; they portrayed the categories of responsibility from Fig. 1. Attribute levels conveyed the characteristics of CSR to the respondents. The descriptors of the attributes and their levels were designed based on an examination of a wide range of CSR reports, identifying examples that illustrate the elements from Fig. 1. The descriptors merge activities of companies considered as leaders in responsibility with those of major hotel chains to fit the holiday context (in the next section we present in more detail how the theoretical elements were converted into practical items).

The instrument was tested and refined with multiple pilots before data collection, and the final wording further reflected views of industry professionals who interact with retail clients. These measures were taken to ensure realism that, in choice modeling, forms the basis for the replicability of a choice experiment (Hensher et al. 2015). As we expected consumer demand for CSR to be latent, we did not use consumer interviews to develop the descriptors of the attributes and their levels. This avoided bias toward types of activities that hotels currently advertise. Table 1 presents all eight attributes and their levels, and the link between the theoretical framework and the choice task items. The eight attributes remained the same across the 24 choice tasks, but their attribute levels varied according to the experimental design, making each task unique. This permitted us to infer the impact of the attributes and their levels on choice (see Fig. 3 for an example choice task).

The orientation of company CSR policy was operationalized by presenting respondents with a single CSR activity most representable of the initiatives the portrayed hotel undertakes. Practical actions represented the three orientations from Fig. 1: environmental sustainability, ethics, and philanthropy. Water use minimization, ubiquitous in CSR reports, denoted environmental sustainability. Pay fairness, also a commonly reported initiative, represented an ethical orientation, as fairness was deemed to match well with ethics. Membership of 1% for the planet, an initiative popular among companies deemed forerunners in CSR, represented a philanthropic orientation.

The distinction between a single example of an initiative orientation and a general focus on a stakeholder group through many initiatives was crucial to allow testing a range of CSR orientations and stakeholder emphases while keeping the alternatives logically coherent and mutually exclusive (Hensher et al. 2015). The attribute ‘main focus of responsibility’ denoted the general target groups (emphases) of the majority of responsibility linked initiatives by the portrayed hotel. The survey highlighted the potential issues linked with tourism to represent an emphasis on customers’ own responsible consumption behavior. The remaining three emphases the hotel could choose focused on the other external stakeholder groups as synthesized earlier (Table 1).

In the scenarios, we used the difference between general donations and voluntary development initiatives that match hotel business to depict CSR fit with business. The dominant nature of philanthropy as a CSR activity supported this choice (Carroll and Buchholtz 2015; Peloza and Shang 2011). The four styles of CSR action were communicated to respondents through a range of verbs that were deemed representative of the styles during the piloting. Finally, CSR verification was operationalized with a difference between independent accreditation and in-house reporting, a typical division in CSR reports.

Attitudinal Variables

In addition to the choice tasks, our hybrid model included two latent variables for which we collected attitudinal data: social desirability and cynicism biases. Following Steenkamp et al. (2010), 12 attitudinal questions on SD bias were taken from Paulhus’ (2002) moralistic response tendencies scale. We modified one question to its negative form (‘I never drive faster than the speed limit’) to achieve balance in question keying. Despite being answered on a seven-point Likert scale of agreement, the questions produce binary data (bias/no bias), as only the two strongest alternatives are considered to represent propensity for bias, while the rest signify no bias (Paulhus 2002). However, latent variable indicators in HCMs must be measured on an ordinal scale to represent variation, and to achieve the continuous scale required by the analysis, several such indicators are needed (Abou-Zeid and Ben-Akiva 2014). We converted the binary data to three ordinal indicators on a five-point Likert scale (SDLik1, SDLik2, SDLik3) using Kuokkanen’s (2017) transformation.

The revised Hunter scale (Lee et al. 2010) was selected to indicate cynicism for its business orientation. Three questions were modified from the ‘Trust Corporations’ subconstruct, but as the construct also included questions on politics, a fourth was adapted from the ‘Corporate-Political Integrity’ section. Differing from SD bias, all questions were measured directly on a five-point Likert scale expressing a level of agreement with the statements, and no further conversion was required.

Population and Sample

The study population was individuals in the UK who had considered a trip to the western Mediterranean or Canary Islands region during the past 10 years and who were at least 18 years old. Respondent screening aimed to verify that they were familiar with the study scenario and in charge of their travel choices; both aspects are crucial for choice validity (Hensher et al. 2015). Qualtrics, a market research company, arranged the sample that was a consumer panel with 308 qualifying responses (2464 choices). The sample exceeded the minimum size of 227 responses indicated by the design software for statistically efficient estimators.

The gender balance of the sample was effectively even at 51.9/48.1% female/male. The median age of respondents was 47.5 years, ranging from 18 to 86 years. 43.5% of the sample had a bachelor’s degree or higher. For modeling purposes, we split the sample into four age categories based on generational divides: Generation Y (< 30 year), Generation × (30–51 year), Baby Boomers (52–70 year), and the Silent Generation (> 70 year), with Generation × the largest group. Income among the sample was slightly skewed toward higher income categories, which was in line with expectations, as people with higher income are more likely to consider holiday travel.

Respondents also disclosed the number of previous trips to a beach destination in the Mediterranean or Canary Islands, similar to the scenario in the survey. The average number of trips was six while the median was 2.2. This wide gap reflects some individuals that frequently travel to the region. Based on these results, three categories of travel activity were defined for testing model specification: low-, medium-, and high-frequency travelers. Medium-frequency travelers had visited the area more than twice, and high-frequency travelers more than six times.

Model Specification, Reliability, and Validity

Before estimating the hybrid model, we verified the validity and reliability of the latent variables. First, following Bierlaire (2016a), an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to examine the structure of the latent bias variables. Both Kaiser–Meyer Olkin measure of sampling adequacy at 0.661 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (p < 0.001) indicated the data were suitable for factor analysis (Hair et al. 2014). The analysis was conducted using principal axis factoring with Varimax rotation to interpret emergent factors. The three SD bias indicators (SDLik1, SDLik2, SDLik3) and three of the four cynicism indicators (Cyn1, Cyn2, Cyn3) demonstrated factor loadings above 0.6 on their respective factors supporting convergent validity (Hair et al. 2014). With no notable cross-loadings, the discriminant validity of the resulting SD and cynicism bias constructs was acceptable. A CFA further supported convergent and discriminant validity. Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was used to verify the reliability of the two constructs, and it supported both SD bias (α = 0.801) and cynicism bias (α = 0.720) to be reliable (Nunnally 1978).

Before fitting the hybrid choice model, several latent variable specifications were tested without the choice component. During the final estimation, the latent variable and choice components of the model were solved simultaneously for optimum efficiency (Bierlaire 2016a). Earlier examples suggest that the latent variable component can include explanatory factors without full statistical significance (Bierlaire 2016a; Kim et al. 2014). Adopting this practice, high education level, defined as Master’s degree or higher (Table 2; Education high, p = 0.09), and annual income between 13 and 19 k GBP (Income 13 to 19 GBP, p = 0.01) were retained in the structural model of cynicism bias. Similarly, annual income between 19 and 64 k GBP (Income 19 to 64 GBP, p = 0.08) was kept in the structural model of SD bias. Each model also included a significant error component (\({\sigma }_{CB}\): p < 0.001, \({\sigma }_{\mathbf{S}\mathbf{D}\mathbf{B}}\): p < 0.001). The coefficient and the variance of the first indicator variable were normalized to one for identification purposes (Bierlaire 2016a).

Results

The HCM model was estimated with the maximum simulated likelihood estimator using PythonBiogeme 2.5 (Bierlaire 2016b). The final specification results used 1000 Modified Latin Hypercube Sampling draws from a normal distribution, and the estimation was further tested for consistency with 1500 draws. The explanatory power of the model is relatively high (\({\overline{\rho}}^{2}\)= 0.602) and clearly exceeds the suggested significance criteria of 0.3 (Hensher et al. 2015). Thus, our overall framework is capable of explaining consumer choice of products that include CSR components. As all CSR characteristics were effects coded in the design, estimator coefficients and standard errors for the omitted (base) levels were calculated separately and are presented in Table 3.

The survey included three attributes related to hotel choice but not connected with responsibility to create a realistic choice situation: distance to beach, location relative to a town and price. All are significant relevant to choice and the coefficient signs are intuitively correct; longer distance to beach, higher price, and a location out of town all create negative utility. These results support the notion that the respondents found the scenarios realistic and that their real taste preferences guided their choices without a significant distortion created by the survey situation. These factors reinforce the reliability and validity of findings related to CSR characteristics.

An alternative specific constant (ASC) was specified for the ‘Some other hotel’-alternative (ASCother hotel = − 22.5, p < 0.01). The negative sign can be considered to represent respondent regret from an inability to choose from the two hotels offered. Thus, it supports the validity of the model by accounting for situations where a respondent was not willing, or able, to choose either of the two alternatives provided with details.

The results of the three categories of CSR strategy formulation reveal significant differences in preferences over the characteristics. With respect to CSR orientation, neither environmental sustainability nor ethical orientation has a significant impact on choice, and thus consumers cannot be influenced by such characteristics. Ethical orientation, however, demonstrates significant moderation by SD bias among above medium-frequency travelers (SDB ethics × TravelAbvAve = 0.0907, p = 0.02) and creates a difference between stated responses and reality. Philanthropy orientation contributes to a significant negative utility (Orientation philanthropy = − 0.173, p < 0.01), signaling that while the choice between the ethical and sustainability orientations is irrelevant, financial donations are perceived poorly by respondents.

Respondents appreciate the natural environment as a stakeholder focus (SH emphasis environment = 0.1955, p = 0.01), and local community as an emphasis also creates positive utility and contributes significantly to choice (SH emphasis local community = 0.163, p < 0.01). Supplier focus fails to influence choices, and it induces a significant negative social desirability bias among the silent generation (SDB supplier × GenSil = − 0.0825, p = 0.04). Interestingly, this generation seems to find declaring a supplier emphasis undesirable in a survey, a form of socially desirable responding. In a survey without bias incorporated, suppliers would seem even less important to choice. The respondents steer away from delving into the potential adverse impacts of their holidays; focus on consumers produces clearly negative utility (SH emphasis consumer = − 0.441, p < 0.01), but the characteristic was prone to a positive SD bias among the baby boomer and silent generations (SDB consumer × GenBB&Sil = 0.116, p < 0.01). The latter result implies that these two generations understand the importance of responsible consumption but do not act accordingly, distancing stated responses again from reality.

The impact of an initiative’s fit is not a significant choice criterion and thus is not deemed a characteristic of consumer demand for CSR. Instead, good fit is perceived socially desirable among the baby boomer generation (SDB fit high × GenBB = 0.0451, p = 0.05), a fourth example of a situation where stated responses and reality differ. This finding could explain why the role of fit has been debated in the literature, and it provides a basis for further investigation.

All styles of CSR action proved significant to choice, with proactive and reactive initiatives creating a positive impact (Style proactive = 0.171, p = 0.01; Style reactive = 0.245, p < 0.01). Interestingly, the results suggest that consumers do not discriminate between the two styles, a finding unexpected based on previous research. Whether the difference between the two styles was significant cannot be analyzed due to the effects coding selected during the design. Both inactive and counteractive styles produce negative utility, a result consistent with expectations (Style inactive = − 0.229, p = 0.02; Style counteractive = − 0.187, p = 0.04). Also, baby boomer respondents perceive support for reactive responsibility socially undesirable to state (SDB reactive × GenBB = − 0.103, p = 0.01), a finding that could explain why proactive CSR has constantly been found preferable over a reactive style. Counteractive style is moderated by cynicism bias among female respondents (CB counteractive × GenderF = − 0.0791, p = 0.03). This result suggests that cynicism prompts women to react even more strongly against such a style when surveyed, a finding consistent with counteractive CSR and the strong stimulus of the survey situation causing increased negativity.

Externally verified evidence has a positive impact on choice (Verification external = 0.135, p < 0.01) and thus companies should pay attention to the type of facts they provide regarding their responsibility. In light of the greenwashing allegations discussed earlier, we tested this characteristic for moderation by cynicism bias but found none.

Discussion

How Should Companies Manage Strategic CSR?

As multiple CSR characteristics influence choice, our results support the notion that CSR can respond to consumer demand for ethical business conduct and create a competitive advantage in business based on the strategic framework (Fig. 1). Furthermore, there is a mix of positive and negative estimators, signaling that respondents demonstrate clear preferences for the categories and characteristics offered. Echoing McWilliams and Siegel’s (2010) proposition of hedonic demand analysis, it seems possible to identify specific CSR characteristics that respond to consumers’ latent CSR demand and convert it into actual demand. Our findings also resonate with studies that have found preferences for individual components of CSR (Auger et al. 2008; Peloza and Shang 2011). Based on our conceptual framework and the results in Table 3, we present an integrative strategic CSR management framework that enables the required C–C congruence (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001) for CSR to impact choice and form a competitive advantage (Fig. 4). The diagram depicts the CSR characteristics that impact consumer choice significantly as solid-line rectangles, while dashed-line rectangles indicate non-significant characteristics. Signs indicate the direction of the impact on choice and asterisks note where biased responses were detected.

Challenges in CSR Strategy Formulation

Several characteristics in CSR strategy formulation demonstrated low importance to consumer choice. These findings help to understand why strong consumer interest in responsibility expressed in surveys does not yet clearly benefit business. Particularly sustainability and ethical orientations of CSR, an emphasis of suppliers as stakeholders, and CSR initiative fit with business are common components of CSR supply. But our results suggest that consumers show limited interest in them.

Questions on CSR Initiative Orientation: What Do Consumers Care About?

Environmental sustainability, as a CSR policy orientation, does not influence choice significantly. This finding is in direct contrast with an emphasis on the natural environment as a stakeholder that consumers perceive positively. This finding highlights the difference between initiative orientation and stakeholder emphasis in our study. The cost-saving nature of environmental initiatives, or fears of greenwashing (Nyilasy et al. 2013; Orazi and Chan 2018), may explain this discrepancy. New ways of transforming environmental sustainability orientation into practical initiatives are needed to benefit fully from customer interest in the natural environment as a stakeholder. For example, the concept of circular economy may be meaningful to consumers, as it focuses on the lifecycle of a product rather than an individual consumption engagement (Andersen 2007), and thus circumvents suspicion of mere cost-savings and greenwashing. Such an orientation could respond to the apparent consumer demand for natural environment emphasis with initiatives that address environmental issues in an orientation meaningful to consumers.

Although our results do not clarify whether consumers identify with specific CSR orientations, it is evident that they do detach from others. Philanthropic initiatives influence choice unfavorably compared to the alternatives, raising questions over the value of cause-related marketing. Merely donating money to good causes without practical actions can be harmful to a company, as it signals a lower engagement in CSR (Peloza and Shang 2011). As philanthropy is a traditional element of CSR (Carroll and Buchholtz 2015), this is alarming. Choosing a CSR orientation between either ethics or environmental sustainability may not yield a clear strategic gain. But focusing only on philanthropy seems to result in a loss.

CSR Stakeholder Emphasis: Stakeholder Salience in the Eyes of Consumers

The low impact of suppliers as important stakeholders was unexpected because earlier research has suggested that supplier focus matters to consumers (Öberseder et al. 2013). A further surprise was the SD bias revealed by this characteristic. The undesirability of supplier focus could result from frustration with the long line of accusations related to supply chains, culminating in high-profile incidents such as the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh in 2013. These events may create a perception of supplier responsibility as mere greenwashing and steer stated consumer emphasis toward other stakeholder groups. The result may also connect with how consumers perceive the relative salience of stakeholders rather than merely signify low importance of supplier treatment. The lack of a cynicism bias supports the latter interpretation.

Our CSR characteristic that projected emphasis on consumers as a stakeholder required responsible consumptive behavior from consumers themselves. Consumers expect companies to behave responsibly, but reciprocity in this aspect seems not to be appreciated. This observation offers at least a partial answer to the question posed by Devinney et al. (2006) as to whether consumers are willing to demonstrate responsibility by making sacrifices in their personal consumption. The answer is ‘no,’ although some respondents realize the social desirability of responsible consumption and their survey answers are biased to disfavor this emphasis less. Such tacit acknowledgment of the importance of consumer responsibility could be a basis for considering the act of consumption in CSR, as suggested by Vitell (2015).

The role of stakeholder emphasis as a demand characteristic was based on consumers expecting companies to be balanced when considering stakeholder needs (Öberseder et al. 2013). This balance, however, does not seem to signify equal shares of attention for each stakeholder. Drawing on the three relationship attributes of stakeholder salience (power, legitimacy, and urgency; Mitchell et al. 1997), our results imply that consumers perceive the natural environment and local communities as mostly legitimate, urgent, and powerful influences. A possible explanation for their importance could be that these two stakeholder groups are outside of a business ecosystem. For this reason, their claims seem more legitimate and urgent than others. Suppliers are part of the business network while the two groups are mostly passive and often reluctant objects of corporate action. Thus, a consumer perspective of stakeholder salience seems to be to create equality by attributing more significance to weaker or less connected groups.

Does CSR Fit Matter?

The role of CSR fit with company business has had both proponents and opponents in previous studies, but the consensus and recent research has favored this characteristic of responsibility (Deng and Xu 2017; Peloza and Shang 2011). Our results challenge the consensus, and the moderating effect of SD bias suggests that earlier findings may have been misled by biased response that could be caused by an attempt to avoid dissonance (Reilly et al. 2018). However, fit as a concept is appealing and has a long line of support to back its importance, and it would be too early to dismiss it as bias. Hence, we propose that in our comprehensive examination, fit with business is embedded in other CSR categories and characteristics. For example, earlier research that has emphasized the importance of ethics has tied ethical orientation closely with the scenario of the study (Auger et al. 2008). It is plausible that consumer identification with ethical initiatives requires a strong link between the initiatives and the industry. Therefore, strong initiative fit with business, while not an individual characteristic of demand, may still affect consumers indirectly together with ethical orientation. Such logic could explain the support for fit in earlier studies and offer room for further analysis related to the role cognitive dissonance plays in strategic CSR management.

CSR Strategy Implementation: A Puzzle of Proactive Versus Reactive Style

Multiple studies have found a proactive CSR style preferable, while a reactive style was ignored or rejected (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006; Groza et al. 2011; Yoon et al. 2006). Our results challenge previous findings on the reactive style, as it appeared to powerfully guide consumers toward responsible choices. Our finding could reflect a view that a reactive approach at least addresses issues, and, if completed diligently, creates improvement. Such a view would represent a contradiction with the earlier finding that considers reactive style to equal mere damage mitigation or image protection (Maignan and Ferrell 2001; Murray and Vogel 1997; Wagner et al. 2009). In a world filled with promises, actions to address existing issues can come across as a genuine effort to do good even when reactive. Furthermore, our findings reveal that the stated value of a reactive style is reduced due to bias, suggesting possible inaccuracy in previous results.

Another potential explanation for this finding is the enhanced range of four alternative styles we offered. Previous research has focused on proactive, reactive, and passive CSR styles but has not combined the three in one study. When faced with all four styles, the attributions linked to reactive style may change. While our results do not contest the importance of proactive CSR, the inclusion of inferior alternatives may increase the relative value of reactive CSR and emphasize it as a viable option.

Theoretical Implications

In this study, we fill a void in our understanding of CSR management by introducing an integrative strategic process that connects managerial and consumer perspectives. The supply and demand framework of CSR (McWilliams and Siegel 2001) omitted interaction between these two elements. Our integrative model implies that cost–benefit analysis does not determine the optimal level of supplying CSR products and associated CSR activities to consumers. Instead, we call for a systematic design of supply that matches consumers’ latent demand for CSR, to be used throughout the CSR management process. We argue for a CSR supply and demand balance where value congruence between the firm and the consumers is established. As a result, the CSR characteristics of a product complement price and traditional purchase criteria in consumer decision-making. Our analysis cannot, however, offer insights into how much CSR characteristics impact choice relative to price and the traditional criteria; this question awaits future research.

We note that a central conclusion in McWilliams and Siegel’s framework is a neutral relationship between CSR and financial performance. They argued that the costs of providing CSR attributes will offset the revenue gains from satisfying demand, negating additional profits. However, this assumption simplifies market dynamics. For example, extra revenue may exceed incremental costs when CSR occurs in oligopolistic industries, or CSR outcomes are used strategically as a form of advertising or a mechanism to raise rivals’ costs (Piga 2002). More importantly, the assumption ignores the role of interaction of firms and consumers in ethical consumption. Our integrative CSR management process indicates that a strong firm–consumer relationship is a key to successful CSR supply. A firm may add significant value to the entire process of ethical product design, production, distribution, and transaction if it converts latent consumer demand for ethical products into active demand for CSR by creating a matching supply. C–C congruence during each stage of the strategic CSR management process forms the foundation for developing a long-term and robust relationship between the firm and its customers. Subsequently, firms will likely accrue profit, corresponding to development of traditional product aspects desired by consumers.

Our strategic CSR management model builds on the concept of C–C congruence established in marketing literature (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). Sen and Bhattacharya (2001) proposed that consumer reactions to CSR rely on the amount of congruence they perceive between a company’s character and their own. Consumer perception of C–C congruence will lead to a positive evaluation of the company and a strong relationship between the two counterparts. However, their C–C congruence framework is based only on a consumer perspective, and the role of the company in the construction of C–C congruence remains undefined. Our model highlights interactions between the firm and its consumers in constructing C–C congruence, and it emphasizes the active role a firm can play in building shared values, reciprocity and committed relationships. We extend the concept of C–C congruence to cover the entire strategic CSR management process and include interactions at each stage. We found that firms can discover substantial new value in developing congruence.

Our conceptual framework and testing results show that strategic CSR management can significantly influence consumer choice of ethical products. This finding complements the understanding of ethical consumption underpinned by theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991). The theory has been widely applied to explain and predict consumers’ intention to purchase ethical products and act on those intentions (Follows and Jobber 2000; Hassan et al. 2016; Papaoikonomou et al. 2011). The theory asserts that consumer purchase intentions are determined by consumers’ attitude toward purchase behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control over the purchase (Ajzen 1991). While it was originally not designed to explain decision-making in ethical contexts, various attempts have been made to modify it by adding extra variables. Nevertheless, the theory and its modifications still cannot fully explain when consumers are willing to purchase ethical products (Chatzidakis et al. 2016). One particular limitation is that the theory assumes that consumer decisions are based solely on consumers’ beliefs, evaluations, and subsequent perceptions of a purchase. The impacts of interaction and CSR management process on consumer decisions are largely ignored. This limitation reflects a wide-spread problem in business research: consumer research is disconnected and isolated from organizational research and “the two sides too often simply fail to speak to each other” (Crane 2008, p. 226). Our framework indicates that firms’ CSR strategies and actions can influence ethical consumers’ decisions. CSR supply with different infusions of characteristics (i.e., different CSR strategy formulation, implementation, and evaluation) impacts consumer choice significantly, and this provides input for new development related to ethical consumption.

Managerial Implications

Our study offers several important implications for practitioners on how they should approach CSR. First, we maintain that demand for CSR products and services exists among consumers, and hence it is possible to gain competitive advantage through strategic CSR management. The key to successful strategic CSR management is to integrate consumer values, expectations and preferences in the formulation, implementation, and evaluation of CSR to create an interaction between the two counterparts. Such integrative thinking and comprehensive design are largely missing in practice and receive little attention in CSR management.

We cannot claim CSR characteristics dominate choice criteria for consumers, but CSR supply with the right mix of characteristics can activate latent demand for ethical business practice and influence potential customers to prefer a firm over its competitors. In practice, the value consumers draw from CSR characteristics differs depending on sociodemographic factors. The preferred CSR characteristics may also differ between industries and over time. Thus, it is essential for managers to understand their business, industry, and the social environment in which they operate to generate optimal strategic CSR for their firms.

The stakeholders that a CSR strategy intends to emphasize should be selected carefully to reflect salience in consumer perception. Companies should avoid direct monetary donations without actual behaviors; for a real strategic advantage, management should fully engage in CSR to become a better corporate citizen. Furthermore, internally produced evidence to demonstrate CSR engagement is inadequate; CSR evaluation should include a mechanism to provide externally verified proof. Our findings indicate that the fit of a CSR initiative with company core business is not as relevant to consumers as has been previously suggested, at least in industries relying on discretionary spending. We do not suggest companies design unfitting CSR strategies, but on occasion, the limits to CSR initiatives set by fit could be ignored. In light of the previous support for the concept however, it would be too early to entirely dismiss CSR fit.

Finally, all CSR initiatives do not have to be proactive in style. Reactive initiatives backed up with substantial external evidence can also favorably influence consumer choice. Research until now has emphasized the role of proactivity in generating a positive perception among consumers. This has put pressure on management to anticipate (perhaps improbably) opportunities for CSR and possibly led to unrealistic expectations of what responsibility can produce. Identifying real issues in an operational environment and reacting to them will also result in positive attributions of the company. Business should not ignore such opportunities.

Societal Implications

Our results also have implications beyond business and consumers. Our integrative strategic CSR framework draws in part on Porter and Kramer’s concept of shared value between business and society, and our experiment supports this idea. Since the 1990s, the mainstream thinking underlying CSR programs has assumed that business and ethics are two distinct areas (i.e., ‘the separation thesis’; Freeman 1994; Wicks 1996; Sandberg 2008), and thus ethics is needed to make business socially responsible. Sun and Bellamy (2010) dubbed this “alienated CSR,” or a situation where CSR is added or attached to business rather than embedded in it. Inevitably, this “alienated CSR” has resulted in the practices of greenwashing and covering-up of corporate social irresponsibility. To improve CSR, the artificial separation thesis must be replaced by a connection thesis that is “… grounded on the interconnectedness of all members of society, mutual interests of self and others, inseparable business from society and the purpose of business to serve the common good” (Sun et al. 2010, p. 11). The common idea between the connection thesis and Porter and Kramer’s strategic CSR is that a business strategy needs to integrate a social perspective into its core framework and business decisions need to benefit both business and society simultaneously, as also suggested by Barnett (2019). Our empirical results indicate that when a firm’s strategic CSR framework integrates managerial and consumer perspectives, it generates significant positive impacts on consumer choice. Therefore, businesses can gain competitive advantage and long-term success if they adopt an integrative over an alienated mode of CSR thinking. For instance, our findings show that CSR orientation toward philanthropy is poorly perceived by consumers and an ethical orientation and fit with business are socially desirable but lack significant impact on consumers. These findings demonstrate that add-on CSR approaches do not look genuine and trustworthy and fail in practice.

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

This research aimed to develop a strategic CSR management process that incorporates supply and demand considerations to influence consumer choice favorably. We expected current consumer demand for ethical business practices to be latent and set out to define CSR characteristics that would create the necessary congruence between companies and consumers for CSR to affect purchasing behavior. The result is the first attempt at a comprehensive approach that integrates key aspects of CSR under one model and suggests how supply and demand may connect in this context. Therefore, the model contributes to the management of strategic CSR and understanding of consumers’ ethical concerns related to business practice.

As a first attempt to create an integrative model of strategic CSR management, the study has limitations. First, the categories and characteristics of responsibility were high-level representations of factors deemed to affect consumer choice. Were CSR characteristics presented numerically, it would have been possible to analyze the impact of responsibility on consumer willingness to pay for CSR and rank the importance of the aspects on choice. Second, the experiment was conducted in a holiday hotel choice scenario that represents discretionary spending. Tourism generated 10.2% of global GDP in 2016 (WTTC 2017) and due to its importance, we believe the results can be generalized to other areas of optional consumption, particularly in the service industries. However, basic spending on items such as food or housing requires further research. The sample of British consumers may limit generalization to different cultural backgrounds, as such aspects are likely to impact consumer CSR preferences.

Choice survey data stand out from most analyses as the respondent only provides the dependent variable, while the independent variables are designed during development (Hensher et al. 2015). Only the attitudinal variables used Likert scale questions. The scenarios included common (non-CSR) hotel choice attributes and a no-choice alternative to avoid context effects. We further incorporated social desirability and cynicism biases in our results as moderators to account for item desirability and transient mood states plausible in ethical surveys. These aspects reduce the risk of common method variance in the results (Podsakoff et al. 2003). However, the choice model method still has limitations. Converting the theoretical CSR categories and characteristics to practical items used in the scenarios can be achieved multiple ways, and despite several rounds of piloting to develop a good match, other presentations could have been possible. This conversion allowed us to test the effect of practical CSR on consumer choice instead of focusing on theoretical constructs. However, the latent nature of consumer demand for such characteristics limited our ability to formulate detailed hypotheses or propositions. Furthermore, despite the pilot study focus on scenario realism, respondents could still develop heuristics in their choice-making that do not correspond to their CSR preferences, a recognized limitation of choice analysis (Hensher et al. 2015). Finally, cynicism bias measurement also created a limitation: despite the strong CSR input in this survey, some cynicism might translate to real actions. However, even if the cynicism discovered was actionable, the value estimated for cynicism bias would convert to an impact on actual choice and not jeopardize results.

From a philosophical perspective, the instrumental approach to CSR adopted in our study could be a limitation, as the results do not address the moral requirement for management to act ethically. However, through the integrative approach, our results reflect the genuine ethical beliefs of consumers. Arguably management may sometimes be incentivized to act in an amoral or even immoral manner to boost financial performance, but consumers lack such incentive. Therefore, we maintain that, while from a management perspective, our research is rooted in the view of CSR as an instrument to improve business performance, the results also incorporate the ethical beliefs of consumers. It follows that such results should, at least theoretically, include an implicit normative aspect in management.

Our findings point to several paths for further research. Instead of dismissing fit from CSR, its possible connection with ethical initiative orientation should be investigated further, also in other industries. Such analysis would deepen the understanding of consumer choice and reveal whether an ethical orientation and fit are indeed only socially desirable. The role of proactive versus reactive initiative style and differences between the two also require further examination before final conclusions. The alternatives for trust production in the CSR context need to be explored further by decomposing external evidence. Defining the most efficient method of trust production will contribute valuable knowledge to management on how to increase the strategic value of CSR.

Our results also point to larger areas of theoretical development. We call for further work that focuses on stakeholder salience from a consumer perspective and develops theory on how consumers make such evaluations. This would complement the current theory that is restricted to a company perspective. We focused on consumer demand for responsibility, but in light of corporate social irresponsibility, it would be equally important to understand which types of unethical conduct influence consumer choice unfavorably, and to what extent. While all irresponsibility must be denounced in practice, theoretical development would benefit from defining the characteristics of irresponsibility that consumers reject. Finally, the mechanisms that create a match between supply and demand, or the firm and the consumer, and lead to a favorable product choice deserve further investigation. Consumers may not approach products with CSR characteristics in a manner identical to conventional products, and the interaction between consumer decision-making and firms’ CSR management process demands more theoretical articulation and experimentation. Through such developments, strategic CSR could reach its full potential and deliver significant benefits to both business and society.

References

Abou-Zeid, M., & Ben-Akiva, M. (2014). Hybrid choice models. In S. Hess & A. Daly (Eds.), Handbook of Choice Modelling (pp. 383–412). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Andersen, M. S. (2007). An introductory note on the environmental economics of the circular economy. Sustainability Science, 2(1), 133–140.

Anderson, J. C., & Frankle, A. W. (1980). Voluntary social reporting: An iso-beta portfolio analysis. The Accounting Review, 55(3), 467–479.

Auger, P., & Devinney, T. M. (2007). Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 76(4), 361–383.

Auger, P., Devinney, T. M., Louviere, J. J., & Burke, P. F. (2008). Do social product features have value to consumers? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 25(3), 183–191.

Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. (1985). An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28(2), 446–463.

Barnett, M. L. (2019). The business case for corporate social responsibility. Business & Society, 58(1), 167–190.

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1304–1320.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baron, D. P. (2009). A positive theory of moral management, social pressure, and corporate social performance. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18(1), 7–43.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53.

Beckmann, S. C. (2007). Consumers and corporate social responsibility: Matching the unmatchable? Australasian Marketing Journal, 15(1), 27–36.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88.

Bierlaire, M. (2016a). Estimating Choice Models with Latent Variables with PythonBiogeme (Series on BIOGEME No. TRANSP-OR 160628). Lausanne.

Bierlaire, M. (2016b). PythonBiogeme: A Short Introduction (Series on Biogeme No. TRANSP-OR 160706). Lausanne, Switzerland.

Brown, T., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: corporate associations and consumer product responses. The Journal of Marketing, 61(January), 68–84.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(3), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2015). Business and society: Ethics, sustainability, and stakeholder management (9th ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Chandler, D. (2015). Corporate Social Responsibility: A Strategic Perspective. New York: Business Expert Press.

Chatzidakis, A., Kastanakis, M., & Stathopoulou, A. (2016). Socio-Cognitive determinants of consumers’ support for the Fair Trade movement. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(1), 95–109.

Choi, S., & Ng, A. (2011). Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(2), 269–282.