Summary

Can a National Health Service afford to provide its patients with an innovative, expensive technology, face to competing alternatives? Trying to answer this question, the economic evaluation of a new medical technology aims at improving the allocation of scarce resources for health care use.

Evaluations are performed using analytical tools, such as Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratios (ICERs), where the additional cost due to a new technology is related to its additional benefits (typically: years of life gained, maybe adjusted for utility). But once an ICER is quantified, it has to be compared with a meaningful threshold value, in order to know whether it is acceptable or not on financial grounds.

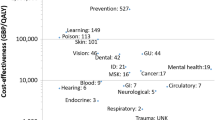

Thresholds are chiefly expressed as ICERs, calculated for technologies already approved by regulatory bodies and about which consensus is widespread. They are generally intended as absolute values (i.e. that can be applied in different environments) and most references are made to the Anglo-Saxon experience (United Kingdom, Australia, USA etc.). But relative thresholds are also suggested in the literature (such as indicators based on a country’s GDP), allowing evaluations which are closer to the features of specific economic/health systems. The classic tool for the potential use of threshold values by policy makers are League Tables (LTs), that is lists of technologies ranked by cost-effectiveness. LTs can be used for a twofold purpose: one (in the theory) would be to efficiently allocate a given amount of resources to different programmes; the other (in practice) is to provide benchmarks for the ICERs of new technologies on trial for adoption. LTs have several limitations, due to non negligible differences in their sources, to time driven changes in their marginality criteria, and several other reasons; so, they should be considered a work in progress rather than a finished one.

It should be stressed that compliance with a threshold value is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a new technology to be accepted. The actual availability of an additional budget is, in fact, a pre-requisite. Of course, the determination of such budget is beyond the responsibility of regulatory bodies; but the underlying problem is often ignored in the ongoing debate.

Last but not least, an original procedure is presented providing an estimate of how much some European countries have (each) de facto spent in order to produce an additional year of life — which could be viewed as one more kind of threshold value. For doing so, data published by OECD (PYLLs, potential years of life lost) were utilised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Bibliografia

Laupacis A, Feeny D, Detsky AS, et al. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization? Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. Can Med Assoc J 1992; 146: 473–81

Tengs TO, Adams ME, Pliskin JS, et al. Five-hundred life-savings interventions and their cost-effectiveness. Risk Analysis 1995; (15) 3: 369–390

George B, Harris A, Mitchell A. Cost-effectiveness analysis and the consistency of decision making: evidence from pharmaceutical reimbursement in Australia (1991 to 1996). PharmacoEconomics 2001; 19(11): 1103–9

NICE. NICE Present Evidence to Health Select Committee. London: NICE, 2002.

Towse A, Pritchard C. Does NICE have a threshold? An external view. In: Towse A, et al. (eds.). Cost-effectiveness threshold: economic and ethical issues. King’s Fund and Office of Health Economics, November 2002

Devlin N, Parkin D. Does NICE have a cost-effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? A binary choice analysis. Health Econ 2004; 13: 437–452

Stafford M, Messori A, Trippoli S, et al. Problems in pharmacoeconomic analyses. JAMA 2000; 284: 1922–1924

Messori A, Santarlasci B, Trippoli S, et al. Controvalore economico del farmaco e beneficio clinico: stato dell’arte della metodologia e applicazione di un algoritmo farmacoeconomico. PharmacoEconomics — Italian Research Articles 2003; 5(2): 53–67

Miller MA, McCann L. Policy analysis of Hepatitis B, Hemophilus influenzae type B, Streptococcus pneumoniae-conjugate and rotavirus vaccines in national immunization schedule. Health Econ 2000; 9: 19–35

Tyagi V, Snigh SK, Sawhney A, et al. Using Gross National Product to calculate acceptable immunisation costs. Deploying cost-effective calculations in reverse. PharmacoEconomics 2003; 21(7): 497–499

Lindholm L, Hallgren C, Boman K, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis with defined budget: how to distribute resources for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Health Policy 1999; 48: 155–70

Lucioni C, Di Maio A, Ravasio R. Il costo della salute in Europa. Prospettive Sociali e Sanitarie 2001; 21: 7–9

Mauskopf J, Rutten F, Schonfeld W. Cost-effectiveness league tables: valuable guidance for decision makers? PharmacoEconomics 2003; 21(14): 991–1000

Drummond M, Torrance G, Mason J. Cost-effectiveness league tables: more harm than good? Soc Sci Med 1993; 37: 33–40

Chapman R, Stone P, Sandberg E, et al. A comprehensive league table of cost-utility ratios and a sub-table of “panel-worthy” studies. Med Decis Making 2000; 20: 451–67

Gafni A, Birch S. NICE methodological guidelines and decision making in the National Health Service in England and Wales. PharmacoEconomics 2003; 21(3): 149–157

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I peer reviewers, per questo articolo, sono stati coordinati da Livio Garattini.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lucioni, C., Ravasio, R. Come valutare i risultati di uno studio farmacoeconomico?. Pharmacoeconomics-Ital-Res-Articles 6, 121–130 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03320630

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03320630