Abstract

Background

An increasing number of older patients are prescribed proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). However, the extent of inappropriate PPI prescribing in this group is largely unknown.

Objective

We sought to identify clinical and demographic factors associated with inappropriate PPI prescribing in older patients and to assess the effects of a targeted educational strategy in a controlled hospital environment.

Methods

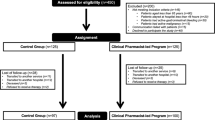

Clinical and demographic characteristics and full medication exposure on admission were recorded in 440 consecutive older patients (mean ± SD age 84 ± 7 years) admitted to a teaching hospital between 1 February 2011 and 30 June 2011. A 4-week educational strategy to reduce inappropriate PPI prescribing during hospital stay, either by stopping or reducing PPI doses, was conducted within the study period. The main outcome measures of the study were the incidence of inappropriate PPI prescribing and the effects of interventions to reduce it.

Results

On admission, PPIs were established therapy in 164 patients (37%). This was considered inappropriate in 100 patients (61%). Lower Charlson Comorbidity Index score (odds ratio [OR] 0.76; 95% CI 0.57, 0.94; p = 0.006) and history of dementia (OR 1.65; 95% CI 1.28, 1.83; p = 0.005) were independently associated with inappropriate PPI prescribing. Interventions to reduce inappropriate PPI prescribing occurred more frequently during and after the education phase (frequency of interventions in patients with inappropriate PPI prescribing: pre-education phase 9%, during education phase 43%, and post-education phase 46%, p=0.006). Prescribing interventions were not associated with acid rebound symptoms.

Conclusions

Inappropriate PPI prescribing in older patients is frequent and independently associated with co-morbidities and dementia. A targeted inhospital educational strategy can significantly and safely reduce inappropriate PPI prescribing in the short term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been used since the early 90s for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders associated with excessive synthesis of gastric acid.[1] This class of drugs exerts a greater acid-suppressing effect than other traditional therapies, e.g. antagonists of the histamine-2 (H2) receptor.[1] There has been a significant increase in the use of PPIs over the last 15 years, particularly in the older population.[2–5] In 2006, PPI prescribing costs amounted to £425 million (€595 million; $US872 million) in England and £7 billion worldwide.[6] Although these drugs were initially considered safe, recent pharmacoepidemiological studies have shown associations between PPI use and short-term (e.g. Clostridium difficile infection and pneumonia) and/or long-term adverse effects (e.g. nutritional deficiencies, hypomagnesaemia, osteoporosis and fractures).[7–9] Despite the inherent limitations of pharmacoepidemiological studies, it has been suggested that frail older patients might be at a particularly high risk of such complications.

The marked increase in PPI prescribing over the last 10–15 years is not entirely accounted for by an increase in the prevalence of gastrointestinal disorders, which suggests an increase in inappropriate PPI prescribing over this period.[2] However, the magnitude of potentially inappropriate PPI prescribing is largely unknown, particularly in patients >65 years, who represent the largest consumer group.[2] The identification of clinical and demographic factors associated with PPI prescribing might help to better target interventions aimed at reducing inappropriate PPI use in specific patient groups. This is particularly important in older patients because of the high prevalence of inappropriate prescribing of drugs other than PPIs; the known age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, which potentially increase the risk of adverse drug reactions; and the increased incidence of the same adverse events (e.g. infections, osteoporosis and fractures) associated with PPI use.[7,10,11]

However, concerns have also been expressed about the potential risks of PPI ‘de-prescribing strategies.’ These would include acid rebound with worsening of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms that might adversely affect a patient’s compliance and the acceptability of the treatment.[12,13] Ideally, such interventions should be conducted, at least initially, in a tightly monitored healthcare environment.

We sought to identify the clinical and demographic factors associated with PPI prescribing and to assess, in an exploratory analysis, the effects of a targeted educational strategy to reduce inappropriate PPI prescribing in a group of frail older hospitalized patients. We hypothesized that a hospital-based educational strategy would increase the probability of success for the following reasons: (i) a close interaction between medical and clinical pharmacy staff would better prompt prescribing interventions in those patients without clear indications for PPI use; and (ii) there is evidence that prescribing interventions conducted in a hospital setting are likely to influence subsequent PPI prescribing patterns in primary care.[14]

Methods

Study Population

We studied a consecutive series of patients >65 years admitted to hospital through an acute geriatric medicine unit (Triage Unit, Woodend Hospital, NHS Grampian, Aberdeen, Scotland, UK) from 1 February 2011 to 30 June 2011. The unit operates a ‘needs-based’ rather than ‘age-based’ admission policy, with patients characterized by aging-related frailty and/or complexity due to multiple medical and/or social issues, rather than single-organ pathology. The study was a clinical audit of inappropriate PPI prescribing and, according to local policy, did not require ethics approval.

New admissions were identified on a daily basis from the admissions register at Woodend Hospital. Data were collected from specific sections in the medical and nursing notes of each patient. The use of similar sources ensured consistency in data collection.

Demographic and Clinical Information

Data were collected on age, sex, history of dementia and usual place of residence. The standard clerking admission form was used to obtain the presenting complaint and the initial diagnosis. The past medical history section of the clerking form was used to identify co-morbidities. This information was used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI encompasses 19 medical conditions weighted with a score of 1–6, with total scores ranging from 0 to 37. The CCI is a valid and reliable measure of co-morbidity.[15,16] Data were also collected on the history or presence of the following gastrointestinal alarm criteria: gastrointestinal bleeding, unintentional weight loss, difficulty swallowing, vomiting and iron deficiency anaemia. These alarm criteria are generally associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer and should prompt further investigations, e.g. endoscopy.[17] Furthermore, daily input in the clinical notes by either junior or senior staff was checked for any evidence of gastric acid rebound or other dyspepsia-related symptoms.

Medication Exposure

A comprehensive medication review was conducted by two investigators (H.H. and H.S.) both on admission and on discharge. Detailed information on pre-admission medication use was recorded, including each drug’s name, total daily dose and frequency. The hospital prescription record (the ‘kardex’) was used preferentially for recording the patients’ prescribed medications as this was based on the most updated medication list in the electronic referral provided by the general practitioner. If this was not available, the medication list on admission was acquired from the medical notes. The kardex record on the last day of hospital stay was used to record medications on discharge.

Criteria for Appropriate Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Prescribing

Potential indications for PPI prescribing were identified from the following sources: electronic referral forms from the general practitioner, admission clerking documents and clinical notes. The following indications for appropriate PPI use were identified from the British National Formulary and the guidelines on the use of PPIs in the treatment of dyspepsia from the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE):[18,19] previous or current peptic ulcer disease, Helicobacter pylori infection/eradication, uninvestigated dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, prevention or treatment of ulcer caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, non-ulcer dyspepsia and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. PPI prescribing was considered appropriate in patients with at least one of these indications.

Educational Strategy on PPI Prescribing

The 30-day educational strategy was conducted between 7 April 2011 and 6 May 2011. One week prior to the education phase, all clinical pharmacists and medical support nurses based either in the Triage Unit or the Geriatric Medicine Wards of Woodend Hospital were sent an email describing the nature of the educational strategy and requesting them to apply a 10 cm × 10 cm ‘sticker’ as visual stimulation on the medication log of each patient who was on PPIs during the education phase. These stickers were available in a special folder accessible in each ward and worked as a reminder, alerting doctors and medical support staff to review the appropriateness of PPI prescriptions on daily ward rounds. A five-page PPI information leaflet was also provided to all patients and carers in the hospital.

From the first day of the education phase, each consultant and medical trainee received a printed standard prescribing recommendation flier. The flier explained the reason for reviewing PPI prescribing, the costs of a 28-day course treatment with low, medium and high doses for each of the five PPIs approved for use in the UK (omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole), and recommended management procedures to optimize PPI use in the hospital. Posters with the same content were displayed on the post boards of each ward. Staff also received weekly email reminders describing PPI prescribing criteria, and recommended doses, for different gastrointestinal conditions and alternative therapeutic strategies.

Finally, four presentations were given at the weekly meeting of the Department of Medicine for the Elderly. These highlighted the clinical purpose of the educational strategy, the necessity of reviewing PPI prescribing to reduce health expenditure, and the need to accurately record the clinical indications for PPI prescribing.

In order to assess the impact of the educational intervention on PPI prescribing, patients were divided into three groups: patients admitted and discharged before the education phase; patients in hospital during the education phase, including patients admitted, but not discharged, during the education phase; and patients admitted after the education phase. The educational strategy was considered successful when a patient had either their PPI dose reduced or stopped during hospitalization.

Statistical Analysis and Sample Size Calculation

Results are expressed as means ± SD, medians and interquartile ranges, or frequencies as appropriate. Variables were tested for normal distribution by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Univariate associations with PPI prescribing were assessed by two-way ANOVA, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Fisher exact test. Variables showing associations with PPI prescribing (p ≪ 0.1) were entered into a binary logistic regression analysis to identify factors independently associated with PPI prescribing.

The study sample size was based on a recent study in a similar population of older hospitalized patients (mean age 79 years) showing a prevalence of PPI use of 38.4%.[20] Assuming a daily admission rate of four to five patients through the Triage Unit during weekdays, the total number of patients during the study period was estimated to be 400–500, including 154–192 potential PPI users. A total of 13 factors were identified a priori to be potentially associated with PPI use (age, gender, dementia, institutionalization, CCI score, smoking, alcohol excess, any gastrointestinal alarm criteria, any appropriate indication for PPI use, and use of either aspirin, clopidogrel, anticoagulants or steroids). Considering at least ten patients per each confounding variable, a minimum sample size of 130 PPI users was required for multivariate analyses. Analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). A two-sided p ≪ 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

PPI Prescribing

A total number of 440 patients were admitted during the study period. PPIs were prescribed before admission in 164 patients (37%; table I). Indications for PPI prescribing were previous peptic ulcer disease (22%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (19%), recent or current peptic ulcer disease (2%), uninvestigated dyspepsia (2%), and non-ulcer dyspepsia (1%). The PPIs most commonly prescribed were omeprazole (64%) and lansoprazole (34%). A few patients were prescribed either pantoprazole (1%) or rabeprazole (1%), whereas no patient was prescribed esomeprazole. Maximum recommended daily doses of PPIs were prescribed in 46 patients (26%).

Patients prescribed PPIs were significantly younger, had more appropriate indications for PPI prescribing and gastrointestinal alarm criteria, were more often prescribed steroids, and were prescribed a higher total number of prescribed medications compared with patients not prescribed PPIs (table I). Regression analysis showed that the presence of appropriate indications for PPI prescribing and a higher total number of medications prescribed were both independently associated with PPI prescribing, although a strong trend was also detected for the presence of gastrointestinal alarm criteria (table II).

Inappropriate PPI Prescribing

PPIs were inappropriately prescribed in 100 patients (61%). Patients inappropriately prescribed PPIs had more often a history of dementia and/or a lower CCI score compared with patients appropriately prescribed PPIs in univariate analysis (table III). Regression analysis confirmed these findings and showed that a history of dementia and a lower CCI score were both independently associated with inappropriate PPI prescribing (table IV).

Educational Intervention on PPI Prescribing

Complete admission and discharge data were available for 60% (n = 60) of patients with inappropriate PPI prescribing on admission (table V). A significant increase in the number of interventions to reduce inappropriate PPI prescribing was observed during and after the education phase versus before the education phase (pre-education phase: 8.6%; during education phase: 42.9%; post-education phase: 45.5%; p = 0.006). Prescribing interventions involved either stopping the PPI (ten patients) or reducing the daily dose (six patients). Regression analysis showed that the different study phases were the only independent predictor of reduced inappropriate PPI prescribing on discharge (odds ratio [OR] 2.91; 95% CI 1.29, 6.56; p = 0.010). There were no patient reports of acid rebound symptoms following PPI dose reduction or withdrawal during the study.

Discussion

Our study showed that PPIs were commonly prescribed in a consecutive series of older hospitalized patients. Their use was often inappropriate and was independently associated with a history of dementia and a lower index of co-morbidity. A 4-week educational strategy targeted at hospital medical and pharmacy staff led to a significant increase in the number of prescribing interventions to reduce inappropriate PPI use. Neither PPI withdrawal nor dose reduction was associated with symptoms of acid rebound, at least in the short term.

The prevalence of PPI use in our study is similar to that recently reported by Pasina et al.[20] in a cohort of older hospitalized patients in Italy. The observed overall prevalence of PPI use in their study was 38%, whilst the use of these drugs was considered inappropriate in 62%.[20] In addition to the presence of appropriate indications for PPI use, our multivariate analysis showed that both the total number of medications prescribed and, to a lesser extent, the presence of gastrointestinal alarm criteria were also independently associated with PPI prescribing. An association between PPI use and total number of medications prescribed has also been reported by Pasina et al.[20] Although PPIs are generally recommended for short-term use, there has been an increasing trend to prescribe them long term together with several classes of drugs potentially increasing gastrointestinal toxicity, e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants and steroids.[21–23] As the use of drugs with potential gastrointestinal toxicity is also associated with prescribing of various other drugs (e.g. cardiovascular and rheumatologic drugs), it is perhaps not surprising that PPI use is associated with ‘polypharmacy,’ either appropriate or inappropriate. Univariate analysis showed statistically significant differences between patients with and without PPIs in the use of steroids, but not aspirin, clopidogrel or anticoagulants. However, the association between use of steroids and PPIs disappeared in regression analysis.

The observation of a strong trend between the use of PPIs and the presence of gastrointestinal alarm criteria, not previously reported in this age group, has potential clinical relevance. Gastrointestinal alarm criteria suggest the possibility of gastric malignancy in dyspeptic patients >55 years, although their accuracy in predicting or excluding malignancy remains largely untested.[24] There is evidence that the use of PPIs in such patients might delay the endoscopic diagnosis of either gastric or oesophageal cancer, with potential consequences in terms of treatment outcomes.[25–27]

A history of dementia and/or a lower CCI score were the only factors independently associated with the inappropriate prescribing of PPIs. The association between dementia and inappropriate PPI prescribing has not been previously reported. It is well known that the presence of significant cognitive impairment might reduce a clinician’s ability to formulate a diagnosis because of the often poorly reliable patient history and symptoms description.[28] Our results suggest that the inappropriate use of PPIs in patients with dementia could be potentially explained by the difficulties in the clinical assessment of dyspepsia in this group. This might lead to the use of PPIs for gastrointestinal symptoms not necessarily associated with increased gastric acid production, e.g. abdominal discomfort, bloating, nausea and reduced appetite. Pending further confirmatory studies, our data suggest that patients with dementia might represent a suitable target group for interventions aimed at reducing inappropriate PPI prescribing.

The observation of an independent association between lower CCI scores and inappropriate PPI prescribing is apparently counterintuitive. Similarly to our study, Pasina et al.[20] observed that patients appropriately prescribed PPIs had a higher number (mean ± SD) of medical diagnoses than patients inappropriately prescribed PPIs (4.9 ± 2.2 vs 4.3 ± 2.3) although this difference was no longer significant in multivariate analysis. One possible explanation is that patients with higher CCI scores are more likely to attend healthcare settings and receive regular monitoring, including medication reviews that might potentially identify inappropriate PPI use. Another explanation is that patients with higher CCI scores might have a higher prevalence of legitimate indications for PPI prescribing. Clearly, more research is warranted to corroborate these findings.

An educational strategy targeted at medical and pharmacy staff across the hospital significantly increased the number of prescribing interventions to reduce inappropriate PPI use. Although we do not have specific information on the acceptability of the educational strategy among healthcare staff, the effect was already detectable during the education phase and persisted during the post-education phase. This suggests that the proposed recommendations are effective at least in the short term. Regression analysis demonstrated that the three different study phases were the only independent predictors of the increased prescribing interventions throughout the study period. This supports the concept that the improved quality of PPI prescribing on discharge was a genuine effect of the educational strategy.

Several studies have previously reported the effects of targeted educational strategies to reduce inappropriate PPI prescribing in various healthcare settings. Krol et al.[29] conducted a patient-centred educational strategy in 160 patients, consisting of an unsolicited standard information leaflet posted to community patients prescribed PPIs for at least 12 weeks, identified through general practices’ databases. The leaflet contained recommendations on the management of dyspepsia, including suggestions to reduce or stop PPIs. Compared with a control group, more patients in the intervention group either stopped or reduced the PPI dose (24% vs 7% at 12 weeks post-intervention; 22% vs 7% at 24 weeks post-intervention).[29] There was no detectable difference in the prevalence or severity of dyspepsia between the two study groups. Batuwitage et al.[30] studied the prevalence of PPI prescribing, either appropriate or inappropriate, in 271 patients admitted to general medical wards in a university hospital. A summary of the findings were posted, together with the UK NICE guidelines on dyspepsia and PPI prescribing, to all the general practices in the area and similar data were collected after 3 and 6 months. No significant changes in the prevalence of PPI prescribing, including inappropriate use (54% baseline vs 51% at 3 and 6 months combined) were observed.[30] van Vliet et al.[31] investigated the effects of implementing a guideline for PPI prescribing, including information on specific indications for PPI use, in 600 patients admitted to respiratory medicine wards (n = 300 pre-intervention; n = 300 post-intervention). This was complemented by other strategies, e.g. departmental meetings and educational reminders during weekly grand rounds. There was a non-statistically significant reduction in the number of patients on PPIs (OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.14, 2.23). Similar results were observed in the sub-group receiving inappropriate PPIs. No significant increases in dyspepsia-associated symptoms were observed within 3 months after discharge.[31]

Our data, albeit preliminary, suggest a meaningful impact of a targeted educational strategy in reducing inappropriate PPI prescribing in an older population during hospital stay. The absence of significant clinical issues related to acid rebound symptoms following either PPI withdrawal or dose reduction is in line with the intervention studies by Krol et al.[29] and van Vliet et al.[31] Theoretically, the increased gastric pH during long-term PPI treatment might stimulate a compensatory release of the hormone gastrin, with a consequent increased activity of the enterochromaffin-like cells. This could lead to excessive gastric acid secretion following withdrawal of PPI therapy.[32,33] Although acid rebound symptoms have been reported in young volunteers, following PPI withdrawal, the evidence is less clear in older patient groups.[12,13,34,35] Advancing age is associated with an intrinsic decrease both in gastrin secretion and in its stimulation during treatment with PPIs in experimental models.[36,37] Whether age-related differences might also explain the relatively lower incidence of dyspepsia-related symptoms following PPI withdrawal or dose reduction is an important clinical issue and needs to be confirmed.

Our study had several important limitations. First, its cross-sectional design did not allow the assessment of a cause-effect relationship between clinical and demographic factors and PPI prescribing. Second, we were unable to determine the PPI treatment duration. It is possible that specific associations between PPI prescribing and clinical and demographic characteristics might depend on temporal prescribing patterns. Third, we were able to collect a full set of admission and discharge data to assess the effects of the educational strategy only in 60% of patients with inappropriate PPI prescribing. This could have been due to a number of reasons, e.g. hospital death or transfer to another hospital with limited access to clinical information. Although this might curtail data interpretation, there were no substantial differences between the group with full data available (n = 60) and the whole group of patients with inappropriate PPI prescribing (n = 100; tables III and V), thus reducing the possibility of bias. Fourth, the educational strategy did not include a control group undergoing standard management. Including a control group during the study period was considered inappropriate because of the significant risk of contamination due to the single study location. Although potential differences between the three study phases were accounted for in regression analysis, it is not possible to fully rule out the potential for temporal variability in patients’ characteristics as an important confounding factor.

Conclusions

Our study has shown that PPIs are commonly prescribed in older hospitalized patients. The analysis of the factors associated with inappropriate PPI prescribing suggests that patients with dementia might represent a useful starting group for medication review strategies. Finally, hospital-based educational strategies might be useful to actively review the need for PPI use and reduce inappropriate PPI prescribing. Further studies in similar healthcare setting are required to confirm these results.

References

Shi S, Klotz U. Proton pump inhibitors: an update of their clinical use and pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 64 (10): 935–51.

Hollingworth S, Duncan EL, Martin JH. Marked increase in proton pump inhibitors use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010; 19 (10): 1019–24.

Chen TJ, Chou LF, Hwang SJ. Trends in prescribing proton pump inhibitors in Taiwan: 1. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003; 41 (5): 207–12.

Martin RM, Lim AG, Kerry SM, et al. Trends in prescribing H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12 (8): 797–805.

Bashford JN, Norwood J, Chapman SR. Why are patients prescribed proton pump inhibitors? Retrospective analysis of link between morbidity and prescribing in the General Practice Research Database. BMJ 1998; 317 (7156): 452–6.

Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ 2008; 336 (7634): 2–3.

Sheen E, Triadafilopoulos G. Adverse effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56 (4): 931–50.

McCarthy DM. Adverse effects of proton pump inhibitor drugs: clues and conclusions. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010; 26 (6): 624–31.

Ali T, Roberts DN, Tierney WM. Long-term safety concerns with proton pump inhibitors. Am J Med 2009; 122 (10): 896–903.

Jackson SH, Mangoni AA, Batty GM. Optimization of drug prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 57 (3): 231–6.

Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 57 (1): 6–14.

Reimer C, Sondergaard B, Hilsted L, et al. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology 2009; 137 (1): 80–7, 87.

Niklasson A, Lindstrom L, Simren M, et al. Dyspeptic symptom development after discontinuation of a proton pump inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105 (7): 1531–7.

Jones MI, Greenfield SM, Jowett S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors: a study of GPs’ prescribing. Fam Pract 2001; 18 (3): 333–8.

de GV, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, et al. How to measure comorbidity: a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56 (3): 221–9.

Hall WH, Ramachandran R, Narayan S, et al. An electronic application for rapidly calculating Charlson comorbidity score. BMC Cancer 2004; 4: 94.

Maconi G, Manes G, Porro GB. Role of symptoms in diagnosis and outcome of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14 (8): 1149–55.

Proton pump inhibitors. In: British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British national formulary. 61st ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2011.

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guidance on the use of proton pump inhibitors in the treatment of dyspepsia. NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance No. 7. London: NICE, 2000.

Pasina L, Nobili A, Tettamanti M, et al. Prevalence and appropriateness of drug prescriptions for peptic ulcer and gastro-esophageal reflux disease in a cohort of hospitalized elderly. Eur J Intern Med 2011; 22 (2): 205–10.

Shrestha K, Hughes JD, Lee YP, et al. The prevalence of co-administration of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. Qual Prim Care 2011; 19 (1): 35–42.

van Dijk KN, ter Huurne K, de Vries CS, et al. Prescribing of gastroprotective drugs among elderly NSAID users in the Netherlands. Pharm World Sci 2002; 24 (3): 100–3.

Ntaios G, Chatzinikolaou A, Kaiafa G, et al. Evaluation of use of proton pump inhibitors in Greece. Eur J Intern Med 2009; 20 (2): 171–3.

Gillen D, McColl KE. Does concern about missing malignancy justify endoscopy in uncomplicated dyspepsia in patients aged less than 55? Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94 (1): 75–9.

Wayman J, Hayes N, Raimes SA, et al. Prescription of proton pump inhibitors before endoscopy: a potential cause of missed diagnosis of early gastric cancers. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9 (4): 385–8.

Naunton M, Peterson GM, Bleasel MD. Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther 2000; 25 (5): 333–40.

Bramble MG, Suvakovic Z, Hungin AP. Detection of upper gastrointestinal cancer in patients taking antisecretory therapy prior to gastroscopy. Gut 2000; 46 (4): 464–7.

Brauner DJ, Muir JC, Sachs GA. Treating nondementia illnesses in patients with dementia. JAMA 2000; 283 (24): 3230–5.

Krol N, Wensing M, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, et al. Patient-directed strategy to reduce prescribing for patients with dyspepsia in general practice: a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19 (8): 917–22.

Batuwitage BT, Kingham JG, Morgan NE, et al. Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgrad Med J 2007; 83 (975): 66–8.

van Vliet EP, Steyerberg EW, Otten HJ, et al. The effects of guideline implementation for proton pump inhibitor prescription on two pulmonary medicine wards. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29 (2): 213–21.

Waldum HL, Arnestad JS, Brenna E, et al. Marked increase in gastric acid secretory capacity after omeprazole treatment. Gut 1996; 39 (5): 649–53.

Sanduleanu S, Stridsberg M, Jonkers D, et al. Serum gastrin and chromogranin A during medium- and long-term acid suppressive therapy: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13 (2): 145–53.

Farup PG, Juul-Hansen PH, Rydning A. Does short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors cause rebound aggravation of symptoms? J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 33 (3): 206–9.

Howden CW, Kahrilas PJ. Editorial: just how “difficult” is it to withdraw PPI treatment? Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105 (7): 1538–40.

Ishihara M, Ito M. Influence of aging on gastric ulcer healing activities of cimetidine and omeprazole. Eur J Pharmacol 2002; 444 (3): 209–15.

Khalil T, Singh P, Fujimura M, et al. Effect of aging on gastric acid secretion, serum gastrin, and antral gastrin content in rats. Dig Dis Sci 1988; 33 (12): 1544–8.

Acknowledgements

Hanifat Hamzat and Hao Sun equally contributed to this work. Arduino A. Mangoni, Joan MacLeod, Joanna C. Ford and Roy L. Soiza formulated the study’s hypothesis and planned the study. Hanifat Hamzat and Hao Sun collected the data. All authors were involved in data analysis and interpretation. Arduino A. Mangoni wrote the manuscript draft. Joan MacLeod, Joanna C. Ford, Roy L. Soiza, Hanifat Hamzat and Hao Sun critically reviewed the manuscript in its final version.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The study received no financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hamzat, H., Sun, H., Ford, J.C. et al. Inappropriate Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Older Patients. Drugs Aging 29, 681–690 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03262283

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03262283