Abstract

Autonomy-supportive teaching strongly predicts positive functioning in both the students who receive autonomy support and the teachers who give it. Recognizing this, the present paper provides conceptual and operational definitions of autonomy support (to explain what it is) and offers step-by-step guidelines of how to put it into practice during classroom instruction (to explain how to do it). The focus is on the following six empirically validated autonomy-supportive instructional behaviors that, together, constitute the autonomy-supportive motivating style: take the students’ perspective, vitalize inner motivational resources, provide explanatory rationales, acknowledge and accept negative affect, rely on informational and nonpressuring language, and display patience. For each act of instruction, I define what it is, articulate when it is most needed during instruction, explain why it is educationally important, and provide examples and recommendations of how to put it into practice.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

They say that no two snowflakes are ever the same. Similarly, among teachers, no two motivating styles are ever the same. Each teacher seems to engage in autonomy-supportive teaching in a unique and personalized way. Still, the combination of a careful eye and a good theory (e.g., self-determination theory; Ryan & Deci, 2000) makes it clear that shared practices do exist among all autonomy-supportive teachers. This chapter is about those shared practices. This chapter casts a spotlight on these commonalities to pursue two goals: (1) identify what autonomy-supportive teaching is and (2) help any teacher who has a desire to do so become more autonomy supportive.

Motivating Style

If you have the opportunity to observe classroom instruction in action, you will sense a characteristic tone that is superimposed over the student-teacher interactions that take place. Sometimes the tone conveyed by the teacher is prescriptive (“Do this; do that”) and is accompanied by a twist of pressure (“Hurry; now!”). Other times the tone is flexible (“What would you like to do?”) and is accompanied by understanding and support. It typically takes only a thin slice of time to identify that tone, because it pervades literally everything the teacher says and does while trying to motivate and engage students.

Motivating Style: What It Is

All teachers face the instructional challenge to motivate their students to engage in and benefit from the learning activities they provide. For some teachers the controlling aspect of what they say and do is particularly salient. The teacher is insistent about what students should think, feel, and do, and the tone that surrounds these prescriptions is one of pressure. Implicitly, the teacher says, “I am your boss; I will monitor you; I am here to socialize and change you.” These teacher-student interactions tend to be unilateral and no-nonsense. For other teachers, the supportive aspect of what they say and do is more salient. The teacher is highly respectful of students’ perspectives and initiatives, and the tone is one of understanding. Implicitly, the teacher says “I am your ally; I will help you; I am here to support you and your strivings.” These teacher-student interactions tend to be reciprocal and flexible. When these differences take on a recurring and enduring pattern, they represent a teacher’s “orientation toward control vs. autonomy” (Deci, Schwartz, Sheinman, & Ryan, 1981) or, more simply, “motivating style” (Reeve, 2009).

Motivating style exists along a bipolar continuum that ranges from a highly controlling style on one end through a somewhat controlling style to a neutral or mixed style through a somewhat autonomy-supportive style to a highly autonomy-supportive style on the other end of the continuum (Deci et al., 1981). Because motivating style exists along a bipolar continuum, what autonomy-supportive teachers say and do during instruction is qualitatively different from, even the opposite of, what controlling teachers say and do during instruction.

Autonomy support is the instructional effort to provide students with a classroom environment and a teacher-student relationship that can support their students’ need for autonomy. Autonomy support is the interpersonal sentiment and behavior the teacher provides during instruction first to identify, then to vitalize and nurture, and eventually to develop, strengthen, and grow students’ inner motivational resources.

Teacher control, on the other hand, is the interpersonal sentiment and behavior the teacher provides during instruction to pressure students to think, feel, or behave in a teacher-prescribed way (Reeve, 2009). In practice, controlling teachers neglect or even thwart students’ inner motivations and, instead, by-pass these motivational resources to (1) tell or prescribe what students are to think, feel, and do and (2) apply subtle or not-so-subtle pressure until students forego their own preferences to adopt the teacher’s prescribed course of action.

The present paper looks carefully at the autonomy-supportive end of the motivating style bipolar continuum, but for the reader interested in a thorough analysis of the controlling motivating style, I recommend discussions on behavioral control (e.g., controlling use of rewards, negative conditional regard, intimidation, and excessive personal control; Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch, & Thogersen-Ntoumani, 2011), psychological control (Soenens, Park, Vansteenkiste, & Mouratidis, 2012), intrusive and manipulative socialization (Barber, 2002), conditional regard (e.g., guilt induction, love withdrawal following noncompliance, love validation following compliance; Assor, Roth, & Deci, 2004; Roth, Assor, Niemiec, Ryan, & Deci, 2009; Assor), or teacher control in general (Reeve, 2009).

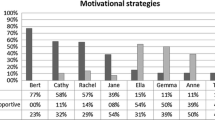

While I conceptualize motivating style within the context of a bipolar continuum, some self-determination theory researchers have begun to study autonomy-supportive and controlling instructional behaviors as two somewhat independent approaches to motivating and engaging students. That is, while some study motivating style as one single characteristic (a bipolar continuum with two opposite ends), others study autonomy-supportive teaching and controlling teaching as two distinct motivating styles (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Haerens, Aelterman, Vansteenkiste, Soenens, & Van Petegem, 2015). To illustrate how autonomy-supportive and controlling instructional behaviors can be measured separately, Figs. 7.1 and 7.2 show two rating sheets. One rating sheet is used to score six acts of autonomy-supportive teaching (Fig. 7.1), while the other is used to score six acts of controlling teaching (Fig. 7.2). This use of separate unipolar scales began because some classroom-based investigations found that autonomy-supportive and controlling instructional behaviors had negative—but not highly negative—intercorrelations (Assor, Kaplan, & Roth, 2002; Assor, Kaplan, Kanat-Maymon, & Roth, 2005). These low intercorrelations were observed because, sometimes, teachers acted in both autonomy-supportive and controlling ways (e.g., giving a command, yet offering an explanatory rationale). Complicating matters on this “one bipolar vs. two unipolar” motivating style issue is that the extent of negative correlation between ratings of autonomy-supportive teaching and ratings of controlling teaching depends on factors such as the rating sheet used, the length of time the teachers are rated (e.g., 5 min teaching episode vs. 1 h classroom observation), and even who the teachers being rated are (Chua, Wong, & Koestner, 2014).

While I continue to conceptualize autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching as opposite ends of a single continuum, I recognize that there is nevertheless some wisdom and practical utility in assessing autonomy support and controlling teaching separately, and this is so for two reasons. First, SDT-based theoretical models show that autonomy-supportive teaching tends to uniquely predict students’ need satisfaction, positive functioning, and well-being, while controlling teaching uniquely predicts need frustration, negative functioning, and ill-being (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Haerens et al., 2015). Second, for most teachers, developing the skill of becoming more autonomy supportive sometimes occurs over time as a two-step process in which the teacher first learns how to be less controlling and then second learns how to be more autonomy supportive.

Motivating Style: Why It Is Important

A teacher’s motivating style toward students is an important educational construct for two important reasons. First, teacher-provided autonomy support benefits students in very important ways. Students who are randomly assigned to receive autonomy support from their teachers, compared to those who are not (students in a control group), experience higher-quality motivation and display markedly more positive classroom functioning and educational outcomes, including more need satisfaction, greater autonomous motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation, identified regulation), greater classroom engagement, higher-quality learning, a preference for optimal challenge, enhanced psychological and physical well-being, and higher academic achievement (Cheon & Reeve, 2013, 2014; Cheon, Reeve, & Moon, 2012; Cheon, Reeve, Yu, & Jang, 2014; Reeve, Jang, Carrell, Jeon, & Barch, 2004; Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Sheldon, & Deci, 2004; Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Soenens, & Matos, 2005; Vansteenkiste, Simons, Soenens, & Lens, 2004). The general conclusion from these experimental studies is that students benefit from receiving autonomy support, and they benefit in ways that are widespread and educationally important, even vital.

Second, teacher-provided autonomy support benefits teachers themselves. Teachers who participate in workshops designed to help them learn how to become more autonomy supportive (compared to teachers in a control group) not only display greater autonomy-supportive teaching, but they further report greater need satisfaction from teaching, greater harmonious passion for teaching, greater teaching efficacy, higher job satisfaction, greater vitality during teaching, and lesser emotional and physical exhaustion after teaching (Cheon et al., 2014). Again, the general conclusion is that teachers benefit from giving autonomy support, and they benefit in ways that are widespread and professionally important.

Two Goals of Autonomy Support

At one level, the goal of autonomy support is clear and obvious—namely, to provide students with learning activities, a classroom environment, and a student-teacher relationship that will support their daily autonomy. That is, the first goal of teacher-provided autonomy support is to deliver the curriculum in a way that supports students’ autonomous motivation and their autonomy need satisfaction in particular. Parenthetically, the goal of controlling teaching is also obvious—namely, to gain students’ compliance with teacher-provided prescriptions (“do this”) and proscriptions (“don’t do that”).

At another level, the second goal of autonomy support is not so obvious—namely, to become in synch with one’s students (Lee & Reeve, 2012). A teacher and her students are “in synch” when they form a dialectical relationship in which the actions of one influence the actions of the other, and vice versa (e.g., the teacher makes a request, students agree but also suggest how that request might be revised or personalized, the teacher accommodates that input); a teacher and his students are “out of synch” when the relationship is unilateral in which the actions of one influence the other but not vice versa (Reeve, Deci, & Ryan, 2004).

Being in synch with one’s students is an important idea to discuss, because it means that the goal of autonomy-supportive teaching is not to do something to motivate students, but, rather, it is to enter into transactional (Sameroff, 2009) and dialectical (Reeve, Deci, & Ryan, 2004) interactions so that students become increasingly able to motivate themselves (Deci, 1995). With transactional and dialectical interactions, what students do (display engagement) affects and transforms what teachers do (display a motivating style) and vice versa. As illustrated in Fig. 7.3a, when students and teachers are in synch, relationship synthesis occurs, as students’ engagement affords teachers a greater opportunity to be responsive and hence more autonomy supportive toward students. Teacher-provided autonomy support, in turn, affords students a greater opportunity to be more engaged in classroom activity. Together, the teacher and student join forces to move toward a higher-quality motivation (students) and a higher-quality motivating style (teachers). When students and teachers are not in synch, however, relationship conflict occurs, as teachers are not responsive to students (because they are not engaged) and students are not responsive to teachers (because they are controlling). Apart, the teacher and students oppose each other and move toward a lower-quality motivation (students) and a lower-quality motivating style (teachers).

For years, I felt that the relations depicted in Fig. 7.3a were sufficient to capture the “in synch” goal of autonomy-supportive teaching. I continue to believe that Fig. 7.3a is likely sufficient for teachers who provide instruction to learners who do not have a long history with the learning activity (e.g., students taking a first course in social studies). In one recent study, however, we provided an autonomy-supportive intervention program to coaches of elite, lifelong, and literally Olympic-level athletes (Cheon, Reeve, Lee, & Lee, 2015). For these athletes, the sport-athlete relation was longer-lasting and more motivationally important to them than was the coach-athlete relationship. That is, athlete motivation was more closely tied to the activity than it was to the coaching relationship. We learned that one of the best ways these coaches could support their athletes’ autonomy was to provide athletes with new ways to practice and train that were significantly more interesting, more need-satisfying, and more relevant to their personal goals than what the athletes were currently doing. That is, to be autonomy supportive, these coaches needed to help their athletes become more in synch with their sport (or learning activity), as shown in Fig. 7.3b. Here the question is how supportive the learning activity is of the person’s inner motivational resources. Teachers can help students become more in synch with the learning activity (or subject matter) by showing students new ways of interacting with the learning activity so that need satisfaction, curiosity, interest, and goal progress become high probability occurrences while need neglect, need frustration, mere repetition, boredom, and goal stagnation become low probability occurrences.

Autonomy-Supportive Teaching in Practice

Using a laboratory procedure, Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, and Leone (1994) experimentally manipulated the presence vs. absence of three interpersonal conditions—provide meaningful rationales, acknowledge negative feelings, and use noncontrolling language. In the Deci et al. (1994) experiment, participants worked on a very uninteresting activity, and the instructional goal was to support students’ internalization and task engagement. This research showed that providing meaningful rationales, acknowledging negative feelings, and using noncontrolling language functioned synergistically as three mutually supportive ways to support autonomy as people engage themselves in relatively uninteresting activities. In the classroom, however, the teacher’s goal is expanded to include sparking engagement in interesting and personally valued activities. To support students’ interest and personal goals, the following interpersonal conditions were added to the operational definition of autonomy support: perspective taking, nurture inner motivational resources, and display patience (i.e., allow students to work at their own pace) (Assor et al., 2002; Edmunds, Ntoumanis, & Duda, 2008; Tessier, Sarrazin, & Ntoumanis, 2008; Reeve, 2009; Reeve, Jang et al., 2004). Together, these six categories of instructional behavior rather comprehensively reveal what autonomy-supportive teachers are saying and doing during instruction.

In practice, an autonomy-supportive motivating style involves the enactment of the following six positively intercorrelated and mutually supportive instructional behaviors: (1) take the student’s perspective; (2) vitalize inner motivational resources; (3) provide explanatory rationales for requests; (4) acknowledge and accept students’ expressions of negative affect; (5) rely on informational, nonpressuring language; and (6) display patience (Reeve, 2009; Reeve & Cheon, 2014). In this section, I overview each of these six aspects of autonomy-supportive teaching and, in doing so, answer four questions:

-

What is it?

-

When is it needed?

-

Why is it important?

-

How is it done?

Juggling six behaviors while simultaneously delivering the curriculum is asking a lot of teachers. To help structure the teacher’s effort to develop the interpersonal skill that is autonomy support, I find it useful to break down autonomy-supportive teaching into three critical moments within the instructional flow, as illustrated in Fig. 7.4. The instructional flow begins with a pre-lesson reflective period in which the teacher plans and prepares the instructional episode (e.g., learning objectives, learning activities, schedule of events). The critical aspect of autonomy-supportive teaching during this time is to take the students’ perspective. Once the instructional episode has been prepared, it is then delivered. As the lesson begins, the teacher invites students to engage in the learning activity. The two critical aspects of autonomy-supportive teaching during this time are to vitalize inner motivational resources and to provide explanatory rationales. As the lesson unfolds, student problems arise (e.g., disengagement, misbehavior, poor performance) that the teacher needs to address and solve if the learning objectives are to be realized. The three critical aspects of autonomy-supportive teaching during this time are to acknowledge and accept negative affect, to use informational and nonpressuring language, and to display patience.

Pre-lesson Reflection: Preparing and Planning

During the pre-lesson reflection period, the critical aspect of autonomy-supportive teaching is to take the students’ perspective, as shown on the left side of Fig. 7.4.

Take the Students’ Perspective: What Does This Mean, When Is It Needed, and Why Is It Important?

Perspective taking is the teacher’s seeing classroom events as if he or she were the students. With perspective taking, the teacher imagines himself or herself to be in the students’ place. It is a cognitive empathic response in which the teacher first understands what students think and feel and second desires for students to think and feel better. The teacher actively monitors students’ needs, wants, goals, priorities, preferences, and emotionality, and the teacher considers potential obstacles students may face that might create anxiety, confusion, or resistance. To do this, the teacher needs to partially set aside his or her own perspective to better understand the students’ perspective (Davis, 2004).

It is always helpful to be mindful of the students’ perspective during instruction, but it is most timely during this pre-lesson creation period. If the instruction-to-come is to align well with students’ inner motivational resources, teachers need to ask, “Will students find this lesson interesting?”, “Could the lesson be made more interesting, more attractive, or more relevant to students’ concerns?”, and “If so, how?”

Taking the students’ perspective is important because the more teachers are able to design instruction to align with students’ motivational assets, the more in synch the teacher and students will be during that episode of instruction. Perspective taking enables teachers to become both more willing (because of greater empathy) and more able (because of greater perspective taking) to create classroom conditions in which students’ inner motivational resources guide their classroom activity. If a lesson is prepared without taking the students’ perspective in mind, the odds increase dramatically that the lesson will ignore or neglect students’ inner motivational resources.

Taking the Students’ Perspective: How to Practice It

As they prepare for instruction, teachers can tap into their experience in teaching similar students in the past and therefore somewhat anticipate the current students’ likely reactions to a wide range of learning activities—and they can make instructional adjustments accordingly. The important point is to use one’s classroom experience to forge new-and-improved answers to these two questions: “Will students find this lesson to be need-satisfying, curiosity-provoking, interesting, and personally important?” and “How can I make this lesson more need-satisfying, curiosity-provoking, interesting, and personally important to my students?”

To begin the lesson, teachers might start with a perspective-enabling conversation that sounds something like the following: “Here is the plan for today. Does that sound like a good use of our time? Any suggestions? Is there anything in this lesson that we might improve?” By starting a lesson in this way, the teacher shows both an openness and a willingness to welcome, ask for, encourage, and incorporate students’ input and suggestions into the lesson plan and into the flow of instruction. Of course, the teacher’s responsiveness to students’ input and suggestions is important. So, the teacher also needs to be willing to incorporate that input and those student suggestions, assuming they are consistent with the learning objective.

During the lesson, teachers can look to students’ preferences and engagement signals to gain the perspective they need to adjust instruction. As to preferences, classroom clickers might be used to solicit students’ collective opinions, choices, and preferences. During instruction, if students display strong and consistent signs of engagement, this confirms that what the students are presently doing aligns well with their inner motivational resources. If students display signs of disengagement or if engagement drops off, that is confirmation that what students are presently doing is neglecting or by-passing their inner motivational resources. Teachers can use these disengagement signals as a trigger to change the flow of instruction away from that which neglects students’ motivation and toward that which involves and vitalizes it.

After the lesson, teachers might conduct a formative assessment. One simple, yet highly informative, formative assessment is to hand out an index card to each student during the last 3 min of class. The index card is blank, except for the following question at the top, “Any suggestions?” If the teacher asks students not to write their names on the card and says that the purpose of the activity is only to improve everyone’s experience in future classes, then students can be expected to communicate to teachers their otherwise private perspective (e.g., “Class is fine, but maybe we could have more group discussion.”). In this exercise, it is important that all students hand in an index card, even if many of those cards are left blank, so that students can be assured that their individual comments will remain anonymous. Students’ responses on these index cards then provide invaluable insight for teachers to incorporate into their future pre-lesson planning and preparing.

Another version of this same formative assessment strategy is to invite students to complete a “weekly reaction sheet” (Rogers, 1995). The student again receives an index card at the end of the week that is blank, except for the following invitation at the top, “Express any feeling you wish that is relevant to the course.” At first, the teacher might offer suggestions, such as “the work you are doing”, “what you are reading or thinking about”, “a feeling about the course”, or “a feeling about the instructor.”

Lesson Begins: Inviting Students to Engage in the Learning Activity

When teachers present a learning activity and invite students’ engagement, student participation in the lesson begins and the next two critical aspects of autonomy-supportive teaching become (1) vitalizing students’ inner motivational resources and (2) providing explanatory rationales. Before inviting students to engage themselves in the learning activity, the teacher makes a judgment, based on perspective taking, whether students are likely to find the activity or behavioral request to be an interesting or an uninteresting thing to do. As shown in the middle of Fig. 7.4, if the teacher forecasts that students will likely find the activity to be a potentially interesting thing to do, then the critical autonomy-supportive instructional behavior becomes to vitalize students’ inner motivational resources. This allows students to experience the activity as a more interesting and need-satisfying thing to do. If the teacher forecasts that students will likely find the activity to be a potentially uninteresting thing to do, then the critical autonomy-supportive instructional behavior becomes to provide explanatory rationales. This allows students to experience the activity as a more important or worthwhile thing to do. Notice in Fig. 7.4 that these two acts of autonomy-supportive teaching occur before “lesson begins.” This is because the critical teaching moment occurs with the engagement invitation. It is important that students first formulate a volitional and heartfelt intention to engage in the lesson (“I want to”) before they actually engage in and learn from that lesson.

Vitalize Inner Motivational Resources: What Does This Mean, When Is It Needed, and Why Is It Important?

Vitalizing students’ inner motivational resources entails using instruction as an opportunity to awaken (involve) and nurture (satisfy) students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as well as students’ curiosity, interest, and intrinsic goals. The teacher involves the students’ inner motivational resources so to make them a central part of the learning activity. Once vitalized, these inner motivational resources are fully capable of energizing, directing, and sustaining students’ classroom activity in productive ways.

Vitalizing inner motivational resources is most timely when teachers introduce a learning activity or when teachers make a transition from one activity to another. It is most needed when teachers seek active engagement from students. It is particularly important because it allows students to feel like origins, rather than like pawns, during learning activities. It allows students to engage in lessons with an authentic sense of wanting to do it, because people in general freely want to do that which is need-satisfying, curiosity-satisfying, interesting, and personally important.

Vitalizing Inner Motivational Resources: How to Practice It

Before teachers can vitalize students’ inner motivational resources, they first need to know what inner motivational resources students possess. An inner motivational resource is an inherent energizing and directing force that all students possess, irrespective of their age, gender, nationality, or academic ability that, when supported, vitalizes engagement and enhances well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Six such resources are highly classroom relevant and are summarized in Table 7.1. In a self-determination theory analysis, these inner resources represent the ultimate source of students’ classroom engagement in learning activities (Reeve, Deci & Ryan, 2004).

Vitalizing inner motivational resources means building instruction around opportunities to have students’ classroom engagement initiated and regulated by the six inner resources listed in Table 7.1. That is, the reason why students engage in the lesson is because it is need-satisfying (inherently enjoyable), meaningful (important), goal-relevant, curiosity-piquing, challenge inviting, etc., and not because they have to (e.g., obey a directive, earn extra credit points). Parenthetically, Table 7.1 does not list intrinsic motivation as an inner motivational resource, though it certainly is a vital inner motivational resource that all students possess. Intrinsic motivation is omitted from Table 7.1 simply because it is defined as the motivation that arises from psychological need satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Teachers can certainly facilitate students’ intrinsic motivation, but the way to do that is to vitalize and support students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Autonomy

Teachers can vitalize students’ need for autonomy by offering them an opportunity for self-direction with the learning activity (Deci, Spiegel, Ryan, Koestner, & Kauffman, 1982; Jang, Reeve, & Halusic, 2015; Nix, Ryan, Manly, & Deci, 1999; Reeve & Jang, 2006). The autonomy need is vitalized when the student experiences a heartfelt affirmation to questions such as “Do I want to learn this?,” “Do I want to do this?,” and “Do I fully agree with this decision and with this course of action?” The best way to have students answer such questions in the affirmative is to ask them what they would like to do within the context of the learning activity and then allow them (and help them) to do it.

Competence

Teachers can vitalize students’ need for competence by offering them an optimal challenge to strive for within a failure-tolerant environment (Clifford, 1990; Keller & Bless, 2008). Teachers can offer students an optimal challenge in many different ways, such as by introducing a standard of excellence, a goal to strive for, a role model to emulate, or students’ own past performance to try to surpass. In practice, teachers can start a lesson by introducing a standard of excellence (e.g., write a paragraph with only active verbs, pronounce a foreign language phrase like an audiotape of a native speaker, run a mile in 10 min or less) and then ask students, “Can you do it?” To the extent to which students perceive that they are making progress toward meeting the challenge embedded within the learning activity, they will feel competence satisfaction while doing so.

Relatedness

Teachers can vitalize students’ need for relatedness by offering them an opportunity to engage in communal social interaction (La Guardia & Patrick, 2008; Ryan & Powelson, 1991). Teachers can do this by giving students an opportunity to engage in face-to-face interaction with a classmate (e.g., a 2-min learning together exercise, cooperative learning). Relatedness need satisfaction occurs to the extent that teachers are able to create opportunities for students to relate their selves to others in an authentic, caring, reciprocal, and emotionally meaningful way.

Curiosity

Curiosity is an emotion that occurs whenever students experience an unexpected gap in their knowledge (Loewenstein, 1994; Silvia, 2008). Curiosity is satisfied when students use exploratory behavior to acquire the information needed to remove that knowledge gap. In doing so, that exploratory behavior (i.e., engagement) generates knowledge growth, learning, and greater expertise. During instruction, teachers can vitalize students’ curiosity in numerous ways, such as asking a curiosity-inducing question (Jang, 2015), introducing suspense about what comes next (Abuhamdeh, Csikszentmihalyi, & Jalal, 2015), and encouraging students to explore a new activity (Proyer, Ruch, & Buschor, 2013).

Interest

Interest is an alert, positive-feeling basic emotion that creates a motivational urge to seek, explore, and investigate; it occurs whenever students have the opportunity to learn something new and to develop greater understanding (Reeve, Lee, & Won, 2015). Interest is like heart rate—it is always there but it also rises and falls; it is a constant presence that can nevertheless be either increased or decreased. It is increased during instruction by offering students new information that exposes a knowledge gap, new experiences (e.g., field trips), new stories or quotations, a brief lesson-centric video presentation, a problem to solve, a how-to demonstration, or a puzzle, riddle, or mystery to solve (Loewenstein, 1994; Schraw, Flowerday, & Lehman, 2001; Silvia, 2006, 2008).

Intrinsic Goals

Teachers can vitalize students’ intrinsic goals by framing the learning activity as an opportunity for personal growth, skill development, an opportunity to develop a closer relationship with others, or an opportunity to contribute constructively to one’s community (Vansteenkiste, Lens, & Deci, 2006; Vansteenkiste et al., 2005). A teacher might, for instance, introduce a writing lesson not only as an exercise in writing but also as an opportunity to become a better writer, saying, “To begin, let’s read this passage by the writer Philip Roth. As you read, notice how good the writing is. Ask yourself what makes this such good writing, and use your answer to discover how to become a better writer yourself.” To the extent that the teacher knows that these students truly want to become better writers, that lesson will be motivating and engaging.

Provide Explanatory Rationales: What Does This Mean, When Is It Needed, and Why Is It Important?

A rationale is a verbal explanation as to why putting forth effort during the activity might be a useful thing to do (Reeve, Jang, Hardre, & Omura, 2002). These verbal explanations help students understand the personal utility within the requested activity, and they therefore help students transform a perceived “worthless activity” (something not worth doing) into a potentially “worthwhile activity” (something worth doing)—something that is truly worth their time, attention, and effort.

Providing explanatory rationales is most timely when teachers request that students engage in a perceived uninteresting or unappealing learning activity, rule, or procedure. It is important because not all lessons, classroom procedures, and behavioral requests can be interesting things to do, at least from the students’ point of view. In those instances, student motivation is highly fragile, as students wonder, “Why do this? Do we really need to do this?” When the teacher provides an explanatory rationale, it helps students make the motivational transition from viewing the activity or requested behavior as something that is not worth doing (because it is unimportant, trivial, or useless to the self) to something that is worth doing (because it is important, valuable, useful to the self). Satisfying explanatory rationales help students accept and begin to internalize the value of the teacher’s request, and it is this perception of value that provides students with a volitional sense of “wanting to” (Jang, 2008; Koestner, Ryan, Bernieri, & Holt, 1984; Reeve et al., 2002).

Providing Explanatory Rationales: How to Practice It

In the course of instruction, teachers often ask students to do things that students may perceive to be uninteresting and unimportant. Examples might include “read the book,” “revise the paper,” “check for spelling errors,” “clean your desk,” “treat others with respect,” “be on time,” “share with your neighbor,” “wait for your turn,” “participate in the group discussion,” “follow the safety procedures,” etc. While students do not really want to do these things, the teacher nevertheless has a good reason for asking students to undertake that particular course of action. The problem is that the teacher’s very good reason is too often unknown to students. When students do not understand or appreciate why the teacher is making a request of them, they tend to view the request as arbitrary, imposed, or simply meaningless busywork. Hence, to support students’ willingness to engage in the requested behavior, teachers need to reveal to students the “hidden value” (the personal utility) of the request.

Several skills are involved in communicating satisfying explanatory rationales. The first is to think reflectively, “Why am I asking students to do this?” If a teacher cannot provide an explanatory rationale, the chances tilt toward the possibility that the request really is unnecessary busywork. Of course, teachers usually have a good rationale for their requests, so there is skill in being mindful of the why? behind one’s requests.

The second skill is to generate satisfying rationales. Rationales such as the following may sound like explanations, but they are deeply unsatisfying to students’ ears: “because I said so,” “because it is on the test,” “because it is good for you,” and “you will understand when you are older.” Before teachers can provide satisfying rationales, they need to first take their students’ perspective and ask if the rationale they have to offer will be well received. For instance, the teacher might believe “so that you won’t bump into others and cause a lot of noise” is a good rationale for “no running in the hallway,” but it is possible that students will not find this same rationale to be personally satisfying. For students, the fun and excitement of running in the hallways may trump the concern over bumping into others and causing a lot of noise. So, teachers need to explain what is truly important, useful, and worthwhile to students about walking rather than running in the hallways.

Consider the common teacher request, “clean your desk.” There is skill in teachers being able to provide a rationale that their students will find to be both authentic and personally satisfying. Having a student clean his or her desk may be important, but the motivational problem to be solved is to help the student come to believe that having a clean desk is an important, useful, and valuable undertaking. In such cases, it is easy for teachers to panic and follow up an explanatory rationale with impatient pressure (“Just do it!”). Effective (satisfying) rationales, however, are those that do not have strings and hidden agendas attached to them. This is the third skill in providing effective rationales: Communicate to students what they do not yet know, which is why the teacher’s request is a valuable and worthwhile thing to do.

A final skill is to provide the explanatory rationale prior to the behavioral request. Most of the time, rationales lag behind the teacher’s request, as in, “After lunch, everyone needs to be sitting in their seat by 1:00, because we have a special activity that begins precisely at 1:00 and I don’t want you to miss out on the fun.” The order of events is “request first, rationale second.” Such an order implicitly communicates primacy to the behavioral request and only supplemental concern for its underlying reason. “Request, then rationale” is better than request only (Reeve et al., 2002), and it is better than request plus a twist of pressure (Koestner et al., 1984). Still, it is motivationally odd to support motivation after, rather than before, the behavioral request. From a motivational point of view, it is more constructive to facilitate the students’ acceptance, willingness, and internalization before making a behavioral request. Hence, a better order of events would be, “rationale first, request second,” as in the following: “We have a special activity that begins precisely at 1:00 and I don’t want you to miss out on the fun. So, after lunch, everyone needs to be sitting in their seat by 1:00.”

In-Lesson: Addressing and Solving Students’ Problems

Student problems can arise during any instructional episode. When they surface, these problems put at risk the quality of students’ classroom motivation, the quality of their learning experience, and the quality of the teacher-student relationship. Table 7.2 lists three commonly occurring student problems: disengagement, misbehavior, and poor performance. In many ways, these problems revolve around the question of “classroom management.” It is during these times in which teachers try to manage students’ disengagement, behavioral problems, and poor performance that the following three aspects of autonomy-supportive teaching are most critical: acknowledge and accept negative affect, use informational and nonpressuring language, and display patience.

Acknowledge and Accept Negative Affect: What Does This Mean, When Is It Needed, and Why Is It Important?

By acknowledging and accepting students’ expressions of negative affect, the teacher shows sensitivity to and a tolerance for students’ concerns, negative emotionality, and problematic self-regulation. The teacher acknowledges that his or her request may conflict with and be at odds with the students’ preferences. The teacher acknowledges that negative emotionality, feelings of conflict, complaining, and resisting may be valid and legitimate reactions to the teacher’s request, at least from the students’ point of view.

Acknowledging and accepting negative affect is most timely when conflict arises between what teachers want students to do (e.g., read a book, revise a paper, pay attention) and what students want to do (e.g., something different, something less demanding, talk with their neighbor).

It is important because acknowledging and accepting negative affect represents the teacher’s best chance of getting students’ engagement-blocking negative affect out of the learning activity and out of the classroom. By considering that students’ negative affect may be valid and legitimate, at least to a degree, the teacher gains an opportunity to restructure the otherwise unappealing or conflict-generating lesson so that it gains the potential to become something that is more appealing and less conflict-generating.

Students’ negative affect involves complaints, resistance, protests, “bad attitude,” and negative emotion and affect. Negative emotion and affect during instruction, such as anxiety, confusion, frustration, anger, resentment, stress, fear, and boredom, tends to interfere with and potentially overwhelm students’ motivation and engagement in the lesson. Complaints, resistance, protests, and “bad attitude” often arise out of students’ perceptions that teacher’s requests, assignments, rules, demands, or expectations are unfair, are unreasonable, are asking too much of them, or simply represent things to do that are neither interesting nor important. The concern is that such negative affect, if unaddressed, will interfere with—a perhaps even poison—students’ engagement and learning. Soothing these negative feelings therefore becomes a prerequisite to motivationally readying students to engage in and benefit from the lesson.

Acknowledging and Accepting Negative Affect: How to Practice It

Teachers often react to students’ expressions of negative affect in a defensive way. Often, teachers do not see students’ resistance as valid (“You’re immature; you’re irresponsible.”) and, hence, counter or otherwise try to change students’ resistance and negative feelings into something more acceptable to the teacher (e.g., “Quit your complaining; now get to work and do what you are supposed to do.”). From a motivational point of view, such teaching behavior runs the risk of replacing students’ engagement-fostering inner motivational resources with engagement-thwarting negative affect and resistance to both the learning activity and to the one providing the learning activity (i.e., the teacher). In contrast, acknowledging and accepting such negative affectivity means taking to heart and even welcoming these expressions as potentially valid reactions to imposed rules, assignments, requests, and expectations.

Here is an example. When the teacher notices that students are generally uninterested in and disengaged in the lesson, the teacher might begin a conversation: “I see that you are not enthusiastic about and interested in today’s lesson. Do I have that right?” These words acknowledge (address) the problem of students’ negative affect (boredom). The teacher might continue: “Yes, we have practiced this same skill many times before, haven’t we?” These words (“yes”) accept the students’ expression of negative affect as potentially valid and legitimate reactions to the instruction. The teacher might continue: “Okay. Let’s see. What might we do differently this time? Any suggestions?” These words (“okay”) become the teacher’s starting point to find the source of the negative affect and to extinguish it. Once done, the teacher now has room to alter (to upgrade) instruction.

There is the key question of whether or not this is an effective instructional strategy. One thing is sure—namely, blaming students (“You’re lazy; you’re irresponsible.”) and trying to change their negative affect into something acceptable to the teacher (e.g., “Quit acting like children, take responsibility for your own learning, act like an adult, and pay attention.”) are a recipe for motivational and engagement disaster. Such an approach to instruction is the equivalent of throwing proverbial fuel on the fire (the problem of disengagement). It not only blocks engagement in the learning activity, but it sends a deeper message that the teacher is out of synch with the students. To solve this problem, it first needs to be addressed, which is the essence of “acknowledge and accept negative affect.” But, to actually solve the problem (to actually dissipate students’ negative affect), the teacher-student dialogue needs to produce fruit. This dialogue begins with something such as, “Okay. What might we do differently this time—any suggestions?” Perhaps students who are anxious, confused, frustrated, angry, stressed, etc. will voice their suggestions, but it is often the case that they first need to know the teacher is sincere in the effort to alter the flow of instruction. Hence, it is often necessary for teachers to take the first step and offer instruction-altering options. These options would be suggestions on how to transform stress-inducing, confusion-inducing, or anger-inducing instruction into instruction that is more confidence-building (de-stressing), clearer (de-confusing), or amicable (de-angering). To do so, the teacher might stop the instructional flow (put down the chalk, close the book, interrupt the discussion) and instead say something like, “Okay, how about a story? Or a demonstration? Or an example? Would you like to learn about out this in a different way? What sounds good?”

Getting negative affect out of the classroom is a difficult problem to solve, especially for emotions such as anger and resentment. But the teacher who acknowledges and accepts students’ negative affect stands a chance of dissipating it. It is a vital autonomy-supportive instructional strategy not only because it helps the short-term teaching goal to extinguish students’ negative affect but also because it helps the long-term teaching goal of being more in synch with one’s students.

Use Informational, Nonpressuring Language: What Does This Mean, When Is It Needed, and Why Is It Important?

Using informational, nonpressuring language refers to the teacher’s reliance on verbal and nonverbal communications to minimize pressure while conveying choice and flexibility. Nonpressuring means avoiding messages that communicate pressure (i.e., the absences of “shoulds,” “musts,” “have to’s,” and “got to’s”). Informational means providing the special insights and tips that students need to better diagnose, understand, and solve the problem they face.

Using informational and nonpressuring language is particularly needed when teachers communicate requirements, offer feedback, and address students’ problems (e.g., those listed in Table 7.2). But informational and nonpressuring language is further useful during practically all teacher communications, as when teachers invite students to engage in learning activities, discuss possible strategies to try, ask students to take responsibility for their own learning and behavior, comment on progress, and generally converse with students.

It is important because it helps maintain a positive teacher-student relationship. It also helps students diagnose their engagement, behavioral, or performance problems while simultaneously maintaining students’ personal responsibility for those problems.

Using Informational, Nonpressuring Language: How to Practice It

Informational and nonpressuring language is communication that is diagnostic, flexible, non-evaluative, and helpful to the student. When facing a student problem such as poor performance or woeful class attendance, the teacher who uses informational and nonpressuring language might begin a discussion by communicating a noticed problem and by asking the student about it: “I’ve noticed that you made a surprisingly low score on the test. Do you know why that might be?” Or, the teacher might ask, “How did you feel about how you did on the test?” The idea is to address the problem while preserving students’ sense of ownership and responsibility for regulating their own behavior and for solving their own problem. The temptation to avoid is to push and pressure the student verbally and nonverbally toward a teacher-specified predetermined solution or desired behavior without enlisting the students’ problem-solving effort (e.g., “You must improve your grades,” “Your attendance is not acceptable,” “I am penalizing you 10 points”). Pressuring, controlling language is pressuring (e.g., teacher raises his or her voice, points assertively, pushes hard, and utters directives), prescriptive (e.g., “Do it this way,” “Can you do it this way?,” “Here, let me show you how to do it.”), and laced with compliance hooks (e.g., “you should, you must, you have to, you’ve got to”) (Assor et al., 2005; Noels, Clement, & Pelletier, 1999; Ryan, 1982).

Addressing a problem in a nonpressuring way gets the conversation off to a good start, but the teacher also needs to help the student make progress in both diagnosing the problem and actually solving it. Often the student has a good understanding of why the problem is occurring (e.g., I performed poorly because I didn’t study.”; “My attendance is poor because I think this class is unbelievably boring.”). If the student can diagnose the underlying cause of the problem, the teacher can turn his or her effort to the students’ willingness to try to cope with the problem. This is why utterances such as “Do you know why that might be?” are important. Alternatively, if the student thinks the teacher is the problem (“You are boring, you are unfair.”), then the teacher might acknowledge and accept the student’s negative affect and ask the student what the teacher might do to help. But if the student thinks the underlying cause of the problem lies within the self, then the teacher might provide informational insights that are outside the student’s experience, such as, “Well, last year, a student had this same difficulty. She too was studying hard but still making poor test scores. One day, she decided to work with a partner. She and a classmate studied together, and this really worked for her. Perhaps you might want to consider a strategy like this too.”

Display Patience: What Does This Mean, When Is It Needed, and Why Is It Important?

Displaying patience means to wait calmly for students’ input, initiative, and willingness. Displaying patience means giving students the time and space they need during learning activities to overcome the inertia of inactivity, to explore and manipulate the learning materials, to ask questions, to retrieve information, to make plans and set goals, to evaluate data and feedback, to formulate and test hypotheses, to monitor and revise their work, to recognize that they are not making progress and need to start anew, to change problem-solving strategies, to revise their thinking, to monitor their progress, to go in their own direction, to reflect on their learning and progress, and to work at their own pace and natural rhythm.

It is timely when students are trying to learn something new, unfamiliar, or complex or trying to develop or refine a skill.

It is important because learning and understanding take time, even if teachers feel that they do not have the class time to give to students.

Displaying Patience: How to Practice It

Giving students the time and space they need to work at their own pace typically means, in practice, that teachers listen, watch, be responsive, and postpone their help and assistance until it is needed and wanted. Teachers watch and observe, but they do not interfere, intrude, or intervene. Patience is the calmness a teacher shows as students struggle to start, to understand, or to adjust their behavior. It often means putting one’s hands in the lap, taking the time to listen and to observe, providing encouragement for effort and initiative, offering hints when students seem stuck, postponing advice until first understanding what the student is trying to do, and waiting for a signal that one’s help, scaffolding, or feedback would be appreciated (Reeve & Jang, 2006). Of course, circumstances such as time constraints and high-stakes testing make it easy to understand why teachers are not patient, but the reason to be patient (motivationally speaking) comes from a deep valuing for the student’s autonomy and an understanding that cognitive engagement (e.g., elaborating, paraphrasing, organizing) and learning (e.g., conceptual change, cognitive accommodation, and deep information processing) are processes that take time.

While patience comes in many flavors, impatience is pretty straightforward and easy to recognize. The impatient teacher pushes and pressures students to go faster, using both verbal (e.g., two-word utterances, such as “hurry up” and “let’s go”) and nonverbal (e.g., clap, clap, clap the hands; snap, snap, snap the fingers; standing over students to communicate that time is up; turning the page before the student is ready) communications. The impatient teacher rushes students to finish what they are doing (e.g., literally grabbing the learning materials out of students’ hands, such as the student’s pencil, keyboard, musical instrument, or worksheet). And they bring the learning activity to a quick close by showing or telling students the right answer (e.g., “Here, let me do this for you.”). The two key problems with impatience are that it shuts down students’ inner motivational resources (to give way to compliance with the teacher’s commands) and it by-passes the actual learning opportunity.

How Do I Know If I Am Becoming More Autonomy Supportive?

In the effort to become significantly more autonomy supportive toward one’s students, it helps to know how one is doing. Becoming more autonomy supportive is a skill, and that skill can be developed and refined. Toward that end, I can suggest three sources of feedback.

-

First, you can ask your students to report their perceptions of your motivating style. To assess students’ perceptions of autonomy-supportive teaching, it is fairly common to use the Learning Climate Questionnaire (LCQ; Williams & Deci, 1996). The LCQ asks questions such as, “I feel understood by my teacher” and “My teacher tries to understand how I see things before suggesting a new way to do things.”

-

Second, you can ask a trained rater to visit your classroom, observe your motivating style, and score your autonomy-supportive teaching using the rating scale shown in Fig. 7.1. It may be difficult to arrange for a trained rater to visit your classroom, but a trusted colleague may take on this same role. Or you might videotape or audiotape your own instruction and use the rating sheet in Fig. 7.1 to self-score your autonomy-supportive teaching.

-

Third, you can monitor students’ engagement signals during your instruction. When teachers are more autonomy supportive, students’ engagement rises, and when teachers are less autonomy supportive, students’ engagement falls (Reeve, Deci, & Ryan, 2004; Reeve & Cheon, 2014). To the extent that you utilize autonomy-supportive teaching, then students should react by showing large and immediate engagement spikes during instruction. This engagement spike should be so large as to be an obvious (easily noticed) classroom event.

These are three reliable sources of feedback. I can also suggest a fourth, though indirect, way of knowing. As teachers become more autonomy supportive, they experience many personal and professional benefits, such as gains in teaching efficacy and job satisfaction (e.g., Cheon et al., 2014). So, the fourth way of knowing would be to ask, “Are these same benefits occurring for me?”

Conclusion

I introduced six empirically validated autonomy-supportive instructional behaviors. Each of these acts of instruction is highly positively intercorrelated with the other five, so it is best to think about a teacher’s overall motivating style. When used in isolation from the other five, none of the individual autonomy-supportive instructional behaviors seems able to produce the classroom conditions and teacher-student relationship that students experience as autonomy support (Deci et al., 1994). Instead, an experience of autonomy support emerges when teachers use the instructional behaviors synergistically. The purpose of this chapter was to help the interested reader learn how to do this.

References

Abuhamdeh, S., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Jalal, B. (2015). Enjoying the possibility of defeat: Outcome uncertainty, suspense, and intrinsic motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 1–10.

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., Kanat-Maymon, Y., & Roth, G. (2005). Directly controlling teacher behaviors as predictors of poor motivation and engagement in girls and boys: The role of anger and anxiety. Learning and Instruction, 15, 397–413.

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., & Roth, G. (2002). Choice is good, but relevance is excellent: Autonomy-enhancing and suppressing teaching behaviors predicting students’ engagement in schoolwork. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 27, 261–278.

Assor, A., Roth, G., & Deci, E. L. (2004). The emotional costs of perceived parental conditional regard: A self-determination theory analysis. Journal of Personality, 72, 47–89.

Barber, B. K. (2002). Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., Bosch, J. A., & Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1459–1473.

Cheon, S. H., & Reeve, J. (2013). Do the benefits from autonomy-supportive PE teacher training programs endure?: A one-year follow-up investigation. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 14, 508–518.

Cheon, S. H., & Reeve, J. (2014). A classroom-based intervention to help teachers decrease student amotivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40, 99–111.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Moon, I. S. (2012). Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 34, 365–396.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Yu, T. H., & Jang, H. R. (2014). Teacher benefits from giving students autonomy support during physical education instruction. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 36, 331–346.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Lee, J., & Lee, Y. (2015). Giving and receiving autonomy support in a high-stakes sport context: A field-based experiment during the 2012 London Paralympic Games. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 19, 1–11.

Chua, S. N., Wong, N., & Koestner, R. (2014). Autonomy and controlling support are two sides of the same coin. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 48–52.

Clifford, M. M. (1990). Students need challenge, not easy success. Educational Leadership, 48, 22–26.

Davis, M. H. (2004). Empathy: Negotiating the border between self and other. In L. Z. Tiedens & C. W. Leach (Eds.), The social life of emotions (pp. 19–42). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Deci, E. L. (1995). Why we do what we do: Understanding self-motivation. New York: Penguin Books.

Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., & Leone, D. R. (1994). Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62, 119–142.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., Schwartz, A., Sheinman, L., & Ryan, R. M. (1981). An instrument to assess adult’s orientations toward control versus autonomy in children: Reflections on intrinsic motivation and perceived competence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73, 642–650.

Deci, E. L., Spiegel, N. H., Ryan, R. M., Koestner, R., & Kauffman, M. (1982). Effects of performance standards on teaching styles: Behavior of controlling teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 852–859.

Edmunds, J., Ntoumanis, N., & Duda, J. L. (2008). Testing a self-determination theory-based teaching style intervention in the exercise domain. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 375–388.

Haerens, L., Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2015). Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 26–36.

Jang, H. (2008). Supporting students’ motivation, engagement, and learning during an uninteresting activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 798–811.

Jang, H. (2015). Three empirical illustrations of a teacher’s use of curiosity-inducing strategies to promote students’ motivation, engagement, and learning. Manuscript under review.

Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Halusic, M. (2015). A new autonomy-supportive instructional strategy that increases conceptual learning: Teaching in students’ preferred ways. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Keller, J., & Bless, H. (2008). Flow and regulatory compatibility: An experimental approach to the flow model of intrinsic motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 196–209.

Koestner, R., Ryan, R. M., Bernieri, F., & Holt, K. (1984). Setting limits on children’s behavior: The differential effects of controlling versus informational styles on intrinsic motivation and creativity. Journal of Personality, 52, 233–248.

La Guardia, J. G., & Patrick, H. (2008). Self-determination theory as a fundamental theory of close relationships. Canadian Psychology, 49, 201–209.

Lee, W., & Reeve, J. (2012). Teacher’s estimates of their students’ motivation and engagement: Being in synch with students. Educational Psychology, 32, 727–747.

Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 75–98.

Nix, G. A., Ryan, R. M., Manly, J. B., & Deci, E. L. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 266–284.

Noels, K. A., Clement, R., & Pelletier, L. G. (1999). Perceptions of teachers’ communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Modern Language Journal, 83, 23–34.

Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Buschor, C. (2013). Testing strengths-based interventions: A preliminary study on the effectiveness of a program targeting curiosity, gratitude, hope, humor, and zest for enhancing life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 275–292.

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44, 159–178.

Reeve, J., & Cheon, H. S. (2014). An intervention-based program of research on teachers’ motivating styles. In S. Karabenick & T. Urdan’s (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (Vol. 18, pp. 297–343). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Reeve, J., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Self-determination theory: A dialectical framework for understanding the sociocultural influences on student motivation. In D. McInerney & S. Van Etten (Eds.), Research on sociocultural influences on motivation and learning: Big theories revisited (Vol. 4, pp. 31–59). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Press.

Reeve, J., & Jang, H. (2006). What teachers say and do to support students’ autonomy during learning activities. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 209–218.

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing high school students’ engagement by increasing their teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28, 147–169.

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Hardre, P., & Omura, M. (2002). Providing a rationale in an autonomy-supportive way as a motivational strategy to motivate others during an uninteresting activity. Motivation and Emotion, 26, 183–207.

Reeve, J., Lee, W., & Won, S. (2015). Interest as emotion, as affect, and as schema (Chapter 5). In K. A. Renninger, M. Nieswandt, & S. Hidi (Eds.), Interest in mathematics and science learning (pp. 79–92). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Rogers, C. R. (1995). What understanding and acceptance mean to me. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 35, 7–22.

Roth, G., Assor, A., Niemiec, C. P., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2009). The emotional and academic consequences of parental conditional regard: Comparing conditional positive regard, conditional negative regard, and autonomy support as parenting practices. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1119–1142.

Ryan, R. M. (1982). Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 450–461.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Powelson, C. L. (1991). Autonomy and relatedness as fundamental to motivation and education. Journal of Experimental Education, 60, 49–66.

Sameroff, A. (Ed.). (2009). The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schraw, G., Flowerday, T., & Lehman, S. (2001). Increasing situational interest in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 211–224.

Silvia, P. J. (2006). Exploring the psychology of interest. New York: Oxford University Press.

Silvia, P. J. (2008). Interest: The curious emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 57–60.

Soenens, B., Park, S. Y., Vansteenkiste, M., & Mouratidis, A. (2012). Perceived parental psychological control and adolescent depressive experiences: A cross-cultural study with Belgian and South-Korean adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 261–272.

Tessier, D., Sarrazin, P., & Ntoumanis, N. (2008). The effects of an experimental programme to support students’ autonomy on the overt behaviours of physical education teachers. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 23, 239–253.

Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41, 19–31.

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Motivated learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic role of intrinsic goals and autonomy-support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 246–260.

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Soenens, B., & Matos, L. (2005). Examining the motivational impact of intrinsic versus extrinsic goal framing and autonomy-supportive versus internally controlling communication style on early adolescents’ academic achievement. Child Development, 2, 483–501.

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Soenens, B., & Lens, W. (2004). How to become a persevering exerciser? Providing a clear, future intrinsic goal in an autonomy supportive way. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26, 232–249.

Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 767–779.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Reeve, J. (2016). Autonomy-Supportive Teaching: What It Is, How to Do It. In: Liu, W., Wang, J., Ryan, R. (eds) Building Autonomous Learners. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-630-0_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-630-0_7

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-287-629-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-287-630-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)