Abstract

Emotions influence the course of a negotiation in at least two ways: First, emotions and cognition are strongly interrelated, thereby affecting negotiators’ decision making (intra-personal). Second, negotiators’ conveyed emotions fulfill important social functions during the negotiation interaction (inter-personal). In this chapter, we argue that negotiating electronically and employing a decision support system affect both the social functions of emotions in negotiations and the interplay between emotion and cognition—sometimes beneficially and sometimes detrimentally. We propose a model integrating theories and empirical results of intra- and inter-personal effects of emotions in negotiations with literature on electronic communication and decision support. The chapter concludes by exemplifying the interrelation between cognitive and social effects of emotions in negotiations, describes how this relationship is mediated by negotiating electronically, and discusses potential avenues for future research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Electronically mediated communication (EMC) has become a central part of organizational life (Hedlund et al. 1998; Baltes et al. 2002; Hinds and Kiesler 2002), and also negotiations are increasingly conducted via electronic media instead of traditional face-to-face (f2f) discussions (Loewenstein et al. 2005; Thompson 2005; Holtom and Kenworthy-U’Ren 2006). Whereas first approaches to support negotiations are rooted in decision-related aspects for individual negotiators, the particular characteristics of negotiations called for the development of negotiation-specific tailored support (Kersten and Lai 2007). Therefore, negotiation support systems (NSS) are seen as a branch of decision support systems (DSS) (Arnott and Pervan 2005, 2008) and “constitute a special class of Group Decision Support Systems (GDSS) designed for noncooperative, mixed-motive task situations” (Anson and Jelassi 1990, p. 186). Further innovations in the fields of information and communication technologies and the increasing need to support negotiations between locally separated people resulted in the development of electronic negotiation systems (eNS). An eNS is commonly defined as “software that employs internet technologies and it is deployed on the web for the purpose of facilitating, organizing, supporting and/or automating activities undertaken by the negotiators and/or a third party” (Kersten and Lai 2007, p. 556). Although a number of systems for e-negotiations with focus on different functionalities have been developed (e.g., Rangaswamy and Shell 1997; Kersten and Noronha 1999; Schoop et al. 2003), at a minimum level they all consist of an individual DSS and an electronic communication channel (Lim and Benbasat 1992). Empirical evidence shows that both of these components have an impact on a variety of issues that are crucial in negotiations such as conflict escalation (Friedman and Currall 2003), trust (Rockmann and Northcraft 2008), fairness (Tangirala and Alge 2006), collaborative behavior (Foroughi et al. 1995; Delaney et al. 1997), decision-making accuracy (Hedlund et al. 1998), negotiation outcomes (Lim and Benbasat 1992; Delaney et al. 1997), or postnegotiation satisfaction (Foroughi et al. 1995; Gettinger et al. 2012a).

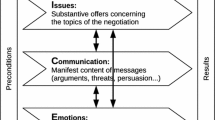

Initially, eNS were designed to direct negotiators toward more rational decision making and task orientation, as well as to help negotiators to avoid emotional behavior that was considered to be dysfunctional (DeSanctis and Gallupe 1987; Anson and Jelassi 1990; Rangaswamy and Shell 1997; Delaney et al. 1997; Foroughi 1998; Jonassen and Kwon 2001). However, recent theory and research show that emotions play a vital role in negotiations (Morris and Keltner 2000; Van Kleef et al. 2010b) and that eNS should also consider the effects emotions have in negotiations (Derks et al. 2008; Broekens et al. 2010). We argue that both components often implemented in an eNS, the communication and the decision component, influence the amount of communicational cues—the richness of a medium—that can be transmitted, as well as cognition and information processing. These two dimensions can be directly linked to two major streams of research on emotions in negotiation: the affect-cognition perspective and the social functional perspective of emotions (Morris and Keltner 2000) (see Fig. 5.1) (see Chap. 2 in this volume).

The first stream of research, represented by the social functional perspective of emotions, emphasizes the inter-personal effects of emotional expressions. Its focus is on the impact that conveyed emotions have on the receiver’s decisions and behavior (Keltner and Kring 1998; Morris and Keltner 2000; Van Kleef et al. 2010b). However, in order to fulfill their social functions, emotions must be conveyed and understood correctly. The bandwidth of a communication channel—the possibilities and limitations of expressing emotional and social content—has a direct impact on the degree to which emotions can be encoded and decoded in e-negotiations. For instance, in f2f negotiations a counteroffer can be accompanied by facial expressions, which are argued to be the major carriers of emotional information (Ekman 1993; Knutson 1996). These can indicate anger, happiness, or regret and clearly signal the social intentions of the reaction to the previous offer. When negotiating via an electronic communication channel that does not provide visual access (e.g., e-mail), alternative ways for communicating emotions must be found. If these are not as efficient as or more ambiguous than facial expressions, emotional expressions forfeit their vital functions in coordinating the negotiation interaction.

The second relevant stream, the affect-cognition perspective, addresses the intra-personal effects of emotions—how the emotions experienced by individuals are interrelated to their cognition and information processing (Bower 1981; Isen 1985; Damasio 1994; Loewenstein et al. 2001). The communication and the decision component influence negotiators’ information processing capabilities and as a consequence mediate the interplay between affect and cognition. In particular, both components commonly implemented in eNS affect the cognitive complexity of a negotiation. For instance, subtle social information is more difficult to encode and decode in an EMC environment making the interaction process more cognitively demanding for the negotiators. However, eNS also provide functionalities reducing the cognitive load and allow the negotiator to expend more cognitive effort to decode and understand emotions.

In the subsequent sections, we address the linkages of the model proposed in Fig. 5.1. First, we provide an overview on the characteristics of electronic negotiations and how the two commonly implemented support components, text-based communication and analytic decision support, influence the encoding and decoding of emotional content. Subsequently, we describe intra- and inter-personal effects of emotions in negotiations and the extent to which they also hold true in e-negotiations. Finally, we elaborate on how the interplay between affect-cognition and social functions of emotions shapes the process and outcome of negotiations as well as how this relationship is potentially mediated by eNS.

Negotiating in an Electronic Environment: Communication and Decision Making

Whereas initial research in the area of electronically supported negotiations primarily focused on economic outcome dimensions of negotiations (Kersten and Lai 2007; Vetschera et al. 2013), the need to additionally consider socio-emotional factors has already been highlighted in the early stages of eNS research (Anson and Jelassi 1990; Bui 1994; Foroughi 1998). Furthermore, e-negotiations should not be considered as simple translations of f2f negotiations into an electronic environment. Rather, the use of electronic means to support the decision making and the communication process shapes the negotiators’ interaction and in consequence the negotiation process and outcome (Ströbel and Weinhardt 2003; Schoop 2010). In the following, we address the two components of eNS, the communication channel and decision support, and how they affect the way negotiators communicate and make decisions during the negotiation interaction.

Communication Channel and (Social) Bandwidth

Communication in negotiations follows the objectives of satisfying the needs and interests of the parties as well as to create a mutual understanding about the negotiation-relevant terms as a requirement for the execution of the reached agreement (Schoop et al. 2010). Communication quality is shaped by the levels of coherence and comprehension of transmitted information including factual information, ideas, and emotions (communication clarity), behavioral aspects of coordination and reciprocity (communication responsiveness), and mutually positively experienced interaction in terms of ease and pleasantness (communication comfort) (Liu et al. 2010).

In f2f negotiations, the creation of a shared sense of understanding about the communication between negotiators and their shared sense of participation in the conversation, referred to as grounding (Clark and Brennan 1991), is based on six characteristics: (i) co-presence within the same surroundings, (ii) visibility of the other negotiator, (iii) audibility of the other negotiator, (iv) co-temporality of expressed communication utterances, (v) simultaneity of sent and received messages, and (vi) sequentiality of turn-taking. In contrast, EMC is characterized by one-directional and intermittent communication—and thus is described as being of lower bandwidth than f2f communication. Most importantly for the present context, due to the lack of visibility and audibility of some communication media employed in e-negotiations, the major carriers of emotional cues available in f2f negotiations are missing. Hence, it is argued that the lower social bandwidth of EMC channels used in e-negotiations limits the extent of, or alters the way socio-emotional information can be transmitted and understood by the counterpart (e.g., Walther 1992, 1996). This, in turn, has a direct effect on the degree to which emotions can fulfill their social functions in e-negotiations.

The communication channel, however, does influence not only how (social) information is transmitted but also information processing by adding the communication features of (i) reviewability and (ii) revisability not available in f2f communication (Friedman and Currall 2003). Reviewability refers to the negotiators’ ability to go through the entire communication record at any time, whereas revisability allows negotiators to work over messages several times before sending them to the counterpart. Moreover, an important characteristic of EMC is whether it is conducted synchronously (e.g., chat) or asynchronously (e.g., e-mail). Synchronous EMC is more comparable to f2f communication as both parties are present at the same time at the virtual bargaining table (Pesendorfer and Koeszegi 2006). Therefore, synchronous EMC is characterized not only by reviewability and revisability, but also by three characteristics present in f2f negotiations, namely co-presence, co-temporality, and simultaneity (Pesendorfer and Koeszegi 2006). In contrast, asynchronous communication does not include the aspects of real time and timely delays between exchanged messages are common. The slower turn-taking tempo in asynchronous communication “allows negotiators as much time between messages as they need to calculate the values of various outcomes and to consider the best counteroffers, and complete transcript of the communication allows for more careful information acquisition” (Moore et al. 1999, p. 39f). Consequently, intricate arguments are only effective in an asynchronous communication setting because the receiver has the possibility to reflect on and digest the arguments. Similarly, deceptive tactics are easier to use in asynchronous communication as it allows to carefully plan the deceptive message (Rockmann and Northcraft 2008). Research on time pressure, which may also be a consequence of the faster or slower turn-taking tempo, has further shown that when not under time pressure negotiators are slower at making concessions and make higher demands, increase integrative tactics, rely less on stereotypes, and are more likely to revise unfounded fixed-pie perceptions (Carnevale et al. 1993; Druckman 1994; De Dreu and Carnevale 2003). Thus, the communication channel does influence not only socio-emotional aspects but also information processing and thereby the interplay between affect and cognition in e-negotiations.

Cues Filtered in or Cues Filtered Out?

One of the primary questions relating to emotions in e-negotiations is whether they can be effectively transmitted at all given that the meaning of messages is determined to a considerable extent by nonverbal and para-verbal cues (DePaulo and Friedman 1998). Early theories addressing socio-emotional issues in EMC such as the lack of social context cues theory (Sproull and Kiesler 1986), social presence theory (Short et al. 1976), and the media richness theory (Daft and Lengel 1984, 1986; Daft et al. 1987) all postulated that the lower social bandwidth of EMC—the restricted number of different cues that can be used for communication—results in a “cues filtered-out” interaction.

Due to their textual nature and the lack of physical presence, most forms of EMC are devoid of these additional cues that serve important functions in encoding and decoding emotional communication. Furthermore, because of the potential lack of visibility and physical proximity, cues about and provided by the social context and the social presence are filtered out (Short et al. 1976; Sproull and Kiesler 1986). This results in reduced awareness of the other, a diminished appreciation of the inter-personal aspects of the interaction, and an increased social distance. Accordingly, early research reported that compared to f2f communication, EMC is less friendly, more depersonalized and hostile, as well as more task-oriented (Kiesler et al. 1984; Siegel et al. 1986; Sproull and Kiesler 1986; McGuire et al. 1987; Rice and Love 1987). Accordingly, e-negotiations should allow only for a limited exchange of socio-emotional and relational information, limit the possibilities to convey and recognize emotions, and alter the emotional climate of the negotiation.

The above-mentioned theories all assume that conveying emotional and relational information in an interaction is bound to the ability of a channel to transmit specific cues. This was soon called into question by a number of scholars positing that the characteristics of the communication channel are but one factor affecting the degree to which emotions can be conveyed and recognized (Lee 1994; Walther et al. 1994; Walther 1995; Zack and McKenney 1995; Carlson and Zmud 1999). Thus, although having a lower bandwidth, e-negotiations might be as suitable as f2f negotiations for establishing inter-personal relationships and exchanging socio-emotional messages. One crucial factor proposed by Walther’s (1992) social information processing (SIP) perspective is time. Different communication channels do not differ with regard to the “amount of social information” but the “rate of social information” that can be exchanged (Walther 1996, p. 10). Accordingly, interacting in a computer-mediated environment does not inhibit but merely decelerate the transmission of socio-emotional information as it “forces both task-related and social information into a single verbal/linguistic channel” (Walther 1994, p. 476). Thus, e-negotiations do not necessarily hinder the exchange of emotions and their respective relational and informational functions but rather require more “real time” and/or additional media-specific communication strategies to convey them. Individuals also adapt to and expand a specific channel in order to filter cues back in (Walther 1996; Carlson and Zmud 1999). Hence, the bandwidth of a medium is determined not only by the medium itself, as posited by media richness theory, but also by the user (Carlson and Zmud 1999)—the more experienced negotiators are with EMC, the more effective they are in encoding and decoding messages and enriching the communication channel to convey socio-emotional content. Thus, although the medium may impose certain constraints on the interaction process, it is the way people make use of the electronic bargaining table that primarily shapes the negotiation interaction (cf. Boudourides 2001).

Conveying Emotional Cues in e-Negotiations

Despite the constraints imposed by a low-bandwidth medium, emotions can be communicated in an electronic environment. The most obvious way of expressing emotions in text-based EMC is indeed the direct and deliberate use of affective language and words such as the expression “this offer makes me really angry” (Van Kleef et al. 2004a, p. 513). Yet, there are also more subtle ways of conveying emotional information in EMC that are specific to the channel and function as substitute to facial expressions and vocal intonation in f2f interactions (see Chap. 6 in this volume).

First, e-negotiators can expand the communication channel to convey emotions by using emotext (Jaffe et al. 1999). Emotext can include intentional misspelling (e.g., “This offer is sooooo bad.”), lexical surrogates (e.g., “hmmmm” to convey hesitation and thoughtfulness), strategic capitalization (e.g., “This offer is NOT FAIR AT ALL.”), grammatical markers (e.g., “!??” in the sentence “Do you consider this offer as fair!??”), or emoticons (e.g., :)) (Jaffe et al. 1999). Other possibilities to transmit nonverbal emotional cues are the length, frequency, and timing of the messages (Walther and Tidwell 1995; Liu et al. 2001). The time of sending and receiving a message, the so-called chronemics, can convey information about dominance or submissiveness, as well as the degree of intimacy or liking (Walther and Tidwell 1995). For instance, a slow reply indicates more dominance than a fast reply, especially when task-oriented and sent at night-time. Also, a slow reply to a task-oriented message may convey a low degree of affection. Furthermore, both higher frequency and longer duration of message exchanges result in stronger impression formations regarding the counterpart (Liu et al. 2001). With respect to length and frequency of messages, Barry and Fulmer (2004) also speak of willful “underutilization” of a channel’s possibilities. For instance, short messages and long response times when negotiating via e-mail signal negative affect. Furthermore, emotionally positive negotiations are characterized by a higher number of exchanged words than emotionally negative interactions (Hancock et al. 2007).

Whereas emotext and willful underutilization are not direct but primarily deliberate expressions of emotions in e-negotiations, negotiators “[…] often imply more information in a proposition than their words suggest or than the surface forms of their utterances denote” (Gibbons et al. 1992, p. 159f). Thus, even if a statement is not explicitly emotional or does not contain electronic paralanguage, it nevertheless conveys an emotional layer based on its content and the way the content is formulated. Furthermore, e-negotiators’ language use does not only allow inferences about their abilities and intentions but also discloses information about their emotions (Sokolova and Szpakowicz 2006). This further implies that the lower the bandwidth of a communication channel, the more important becomes the role of language features in deriving emotional meaning from a message. For instance, the statements “Your offer is simply unacceptable!” and “Unfortunately, we cannot accept this offer.” both inform the counterpart that the sender of the offer is unable or unwilling to accept the offer. However, despite having an identical factual content and no directly expressed emotions, the two messages differ in terms of valance and arousal. Whereas the former contains a certain degree of anger and frustration, the latter rather conveys regret or sadness (Griessmair and Koeszegi 2009). Accordingly, messages do not only consist of the factual content that informs the counterpart about what a negotiator wants, but contain multiple communicative layers (Watzlawick et al. 1967; Schulz von Thun 1981). The different layers neither require distinct messages nor have to be expressed explicitly, but are conveyed simultaneously within the same message. For instance, the type of offers negotiators make and how they are formulated convey not only the factual information about the offer (e.g., price) but at the same time how the sender relates to the receiver (e.g., feelings of dominance, feelings of submission). A more detailed investigation of this phenomenon is provided by linguistic approaches and works based on attribution theory (Weiner 1985). For instance, Schroth et al. (2005) showed that negotiators attribute emotional content to specific negotiation utterances. In particular, statements including negative attributions (“you are being unfair”), telling the counterparts what to do or what they can’t do (“you need to give me a better deal than this one,” or “no, that’s impossible”), appealing to higher sources or blaming (“from a legal standpoint,” or “my division is more important than yours”), as well as labeling the own behavior as superior (“I’m being reasonable”) communicate and trigger negative emotions. Furthermore, linguistic features of written language such as polarization, immediacy, intensity, lexical diversity, and powerful or powerless style convey information of a negotiator’s feelings to the counterpart (Gibbons et al. 1992; Sokolova and Szpakowicz 2006). For instance, language immediacy signals the degree to which negotiators wish to move closer to the counterpart and shows positive or negative directions of the negotiators’ emotions. Emotions conveyed via language immediacy are not expressed explicitly but conveyed via subtle linguistic indicators such as whether a personal pronoun or a content noun is employed or the use of “there” and “he and I” rather than “here” and “we” (Gibbons et al. 1992; Sokolova and Szpakowicz 2006).

More subtle and implicit ways of communicating emotions in e-negotiations, however, also result in more ambiguity. For instance, individuals diverge greatly regarding their emotional perceptions or interpretations of e-mails (Byron and Baldridge 2005). Individuals also tend to be overly optimistic regarding their abilities to judge and interpret the emotional tone of e-mails (Kruger et al. 2005). Furthermore, respondents interpreting the emotional tone of e-mail mock-ups enriched with an emoticon were not directly influenced via the emoticons. Emoticons rather complemented message interpretations and intensified emotionally negative message interpretations (Walther and D’Addario 2001). Similarly, e-mail communication is supposed to suffer from neutrality and negativity effects (Byron 2008). Accordingly, whereas emotionally positive messages tend to be perceived as more neutral than intended by the composer, emotionally negative messages tend to be perceived as more intensely negative than intended.

Decision Support and Cognitive Complexity

The second component of eNS primarily considers negotiators’ decision making processes and impacts the interplay between affect and cognition during the interaction process. The most common approach to supply decision support is the provision of analytic decision support and the visualization of decision-relevant information. An analytic approach uses formal representations and models to help negotiators achieve their goals on an individual and/or a negotiation group level (Sebenius 1992; Raiffa et al. 2002). From an economic perspective, Pareto efficiency of agreements is one core outcome criterion (Tripp and Sondak 1992; Raiffa et al. 2002). However, research argues that human decision makers have problems exploiting the full potential of conflict situations (Neale and Bazerman 1992; Sebenius 1992; Raiffa et al. 2002). As complexity increases, human negotiators face problems comprehending and evaluating all possible solutions (Anson and Jelassi 1990; Foroughi 1998). As the relationship between the level of information processing and the environmental complexity has the shape of an inverted “U” (Schroeder et al. 1967), negotiators face the problem of information overload in particularly complex conflict situations. Therefore, systems providing decision support to their users are seen as an extension of human mental abilities (Kersten and Lai 2007). While the functionalities of systems providing analytic decision support are still expanding, some eNS nowadays provide analytic decision support throughout the entire negotiation process (Kersten and Lai 2010). These systems elicit the individual negotiators’ preferences and provide feedback about the exchanged offers in form of scorings (e.g., utility values) indicating to what extent the offers reflect the negotiators’ individual preferences. Furthermore, several systems additionally offer a graphical presentation of the exchanged offers based on the focal user’s preferences. A graphical presentation of the negotiation history gives an overview of the progress of the negotiation in terms of exchanged offers and reflects the dynamics of the supported negotiation (Weber et al. 2006). Such a problem presentation can serve as external information storage so that not all relevant information has to be kept into human memory (Zhang 1997). Furthermore, graphical decision aids aim to enable negotiators to “read-off” information such as whether the exchanged offers show a trend toward convergence or divergence. This process is called “computational offloading” and refers to the reduced cognitive effort to make informationally equivalent decisions (Scaife and Rogers 1996).

Empirical studies investigating synchronous negotiations show that a decision component alone without communication support is sufficient to improve objective outcome dimensions such as joint outcomes and the fairness of the final agreement (Delaney et al. 1997; Lim and Yang 2007). Similarly, the use of an eNS, consisting of a communication and an analytic decision support component, leads to higher joint (integrative) outcomes (Foroughi et al. 1995; Rangaswamy and Shell 1997), and more balanced (fairer) outcomes (Foroughi et al. 1995) in comparison with f2f negotiations. However, the use of an analytic decision component does not only shape objective dimensions, but also influences the negotiators’ perceptions. Delaney et al. (1997) report that the combined use of decision and communication support compared to a DSS only results in a higher postnegotiation satisfaction in high and low conflict treatments. Furthermore, negotiators using communication and decision support express a higher postnegotiation satisfaction in low and high conflicting treatments (Foroughi et al. 1995). While negotiators perceive the same level of collaborative climate independently of their negotiation mode and the conflict level, negotiators in the f2f setting report to have experienced a higher negative climate in low conflict negotiations (Foroughi et al. 1995). Similar results have been found in asynchronous negotiations. Adding decision support additionally to the communication components leads to proportionally fewer exchanges of preference information, more infrequent usage of hard tactics, and more positive affective behavior (Koeszegi et al. 2006). Furthermore, negotiators also make proportionally more (integrative) package offers as well as concessions and reach more agreements. Similarly, the additional use of a decision component leads negotiators to express significantly more thoughts in negotiations (Schoop et al. 2014). However, the use of an analytic decision component decreases the postsettlement satisfaction of negotiators with relational aspects such as relationship building and mutual concern (Schoop et al. 2014). Vetschera et al. (2006) also found that the perceived usefulness of an analytic component in asynchronously conducted e-negotiations is positively related to the negotiators’ overall subjective assessment of the used eNS.

Regarding visual analytical support based on utility values of exchanged offers in graphical form, Weber et al. (2006) compared asynchronous e-negotiations with and without a graphical presentation of utility values based on the exchanged offers. They report that negotiators require on average 334 words less in their text messages to reach an agreement. The use of such an additional graphical tool seems to help negotiators to clarify and support their arguments so that they require less direct communication. Similarly, another study investigating the effect of presenting the utility values in either tabular or graphical format to users found that negotiators provided with a graphical representation of the negotiation history engage in more integrative negotiation behavior and express a higher postnegotiation satisfaction (Gettinger et al. 2012b). Therefore, graphical decision aids based on analytic considerations can reduce the level of information ambiguity and the reproduced task complexity (Gettinger and Koeszegi 2014).

Overall, negotiating in an electronically mediated environment poses some challenges for negotiators in conveying and understanding emotions. However, e-negotiations also have some distinctive advantages over f2f negotiations resulting from reviewability, revisability, and the potential slower turn-taking tempo of the interaction. Furthermore, providing an adequate decision support component can reduce the cognitive complexity for the negotiators. Although these components were primarily designed to aid negotiators in dealing with rational-economic issues, research has shown that they also impact other crucial factors in negotiations such as communication patterns as well as socio-psychological and emotional dimensions.

Intra- and Inter-Personal Effects of Emotions in e-Negotiations

As discussed in the previous section, EMC alters the way emotions are used and transmitted, and negotiating (a)synchronously or (not) employing a DSS impacts negotiators’ cognitive processes and, in consequence, their emotional experience. In the following sections, we provide an overview on the social functional and the affect-cognition perspective of emotions in negotiations and discuss whether the respective propositions of and findings derived from these perspectives also hold true in an e-negotiation setting. Put differently, we address the influence of emotions on the negotiator who is experiencing them (i.e., intra-personal effects), and the effect of expressed emotions on the counterpart (i.e., inter-personal effects) in e-negotiations. Finally, we outline how the two perspectives work together in shaping the negotiation process and how negotiating in an electronic environment might alter their interplay and, as a result, negotiation dynamics and outcomes.

Emotions and Social Functions: Inter-Personal Effects

The inter-personal approach investigates emotions as a social rather than individual phenomenon (Parkinson 1996; Keltner and Kring 1998; Morris and Keltner 2000; Fischer and Van Kleef 2010; Van Kleef et al. 2010b) (see Chap. 2 in this volume). This so-called social functional approach primarily addresses the relational functions of emotions and the effects that expressed emotions have on the interaction partner. Accordingly, emotions are conceptualized as “other-directed, intentional (although not always consciously controlled) communicative acts that organize social interactions” by communicating “social intentions, desired courses of actions, and role-related expectations and behaviors” (Morris and Keltner 2000, p. 13). In the context of negotiations, at least three emotional functions can influence the course of the interaction (Keltner and Kring 1998; Morris and Keltner 2000; Barry et al. 2004; Van Kleef and Côté 2007): (i) emotions are a central source of information, (ii) can serve as incentives or deterrents, and (iii) are likely to evoke reciprocal or complementary emotions in the counterpart.

Informational and Incentive Functions of Emotions in Negotiations

Negotiations are typically characterized by uncertainty about the counterpart and that negotiators must rely on a number of cues to decide which strategy to employ and which step to take next (Van Kleef et al. 2010b). The emotions displayed by negotiators provide valuable insights about their attitudes and intentions, their orientation toward, and how they perceive the status of a relationship as well as their willingness to agree and whether they conform with the counterpart’s behavior (Daly 1991; Knutson 1996). Factual information such as offers and counteroffers is put into context by the accompanying emotional expressions that aid the receiver in making sense of the received information. Thus, emotions have an important informational, feedback, or signaling function (Keltner and Kring 1998; Morris and Keltner 2000; Barry et al. 2004; Pietroni et al. 2008). For instance, the display of anger may signal the importance of an issue, that negotiators’ limits have been reached, or that they blame the counterpart for frustrating their goals (Van Kleef et al. 2004a; Schroth et al. 2005). Happiness, on the other hand, might indicate that the counterpart is satisfied with the progress of the negotiation but also that his or her limits are not yet reached and that a negotiator may be willing to, for example, make more concessions (Van Kleef et al. 2004a, b). Analogous to the informational function, in their incentive function emotions can serve as positive or negative reinforcers for other individuals’ social behavior (Cacioppo and Gardner 1999; Fischer and Roseman 2007). Negotiators expressing positive emotions such as happiness or gratitude reward their counterparts for the performed behavior, increasing the likelihood that they will continue exhibiting congruous actions. Negative emotions, on the other hand, serve as punishment for a counterpart’s undesired behavior, encouraging an adjustment of the performed course of action. In their function as incentives or deterrents, emotions help to regulate the negotiation interaction.

Emotional Contagion and Reciprocity in Negotiations

Extensive evidence in negotiation research shows that negotiators tend to respond-in-kind to their counterparts and investigate action–reaction sequences and their consequences in negotiations (Olekalns and Weingart 2003; Weingart and Olekalns 2004; Adair and Brett 2005). A similar phenomenon referred to as emotional contagion or emotional reciprocity is also observed with regard to affect (Hatfield et al. 1993; Friedman et al. 2004) (see Chap. 1 in this volume). Emotional contagion designates a process of automatic transfer of affect between interacting individuals (Hatfield et al. 1993, 1994). In other words, when emotional contagion occurs individuals start to feel the emotions expressed by the counterpart resulting in an affective synchronization (Barsade 2002). Emotional reciprocity is limited to the reciprocation of emotional expressions and does not necessarily include that the emotions are also evoked in the counterpart. Indeed, co-occurrence of these two phenomena is more likely; however, “contagion is not necessary to generate emotional reciprocity” (Friedman et al. 2004, p. 374) and vice versa. Furthermore, emotional contagion is more likely to occur in interactions which are characterized by high social and task interdependence (Hatfield et al. 1994; Bartel and Saavedra 2000). As in negotiations the parties are mutually dependent in achieving their goals and have to continuously adapt and adjust their behavior to each other, negotiations can be expected to be characterized by frequent emotional convergence. Finally, affective transfer is generally more likely with high-arousal and negatively valenced emotions (Bartel and Saavedra 2000; Rozin and Royzman 2001; Barsade 2002). Accordingly, it is likely to be the case in negotiations that spirals of negative affect are more easily triggered and maintained than positive dynamics.

The Social Functions of Emotions in e-Negotiations

By fulfilling the three aforementioned social functions, “emotions provide structure to social interactions, guiding, evoking, and motivating the actions of individuals in interactions in ways that enable individuals to meet their respective goals” (Keltner and Kring 1998, p. 3). A number of studies investigated the functions and effects of expressed emotions in an EMC setting in which the negotiating parties had no visual access and communicated with each other only via text. These studies primarily focused on anger and happiness and showed, for example, that negotiators tended to concede more when the counterpart exhibited anger rather than happiness (Van Kleef et al. 2004a, b). The emotions expressed by their counterparts are used as information to infer their limits and adjust the own offers accordingly (Van Kleef et al. 2004b). This relation is, however, mediated by information, appropriateness, and power. Studies conducted via EMC show that negotiators are more influenced by the counterparts’ emotional expressions when the informational value of emotions increases and they are motivated and able to consider them, for instance, when the offer is equivocal and they are not under time pressure (Van Kleef et al. 2004a, b; Van Kleef and Côté 2007). Negotiators also tend to retaliate rather than concede when the expression of anger is considered inappropriate (Van Kleef and Côté 2007). The counterparts’ reaction to expressions of anger and its effect on value claiming and reaching an agreement is further dependent on whether the counterparts are vulnerable and the quality of their alternatives (Friedman et al. 2004; Sinaceur and Tiedens 2006; Van Kleef and Côté 2007). Research on the information function of emotions shows that providing affective rather than solely numeric statements increases the impact of a negotiator’s toughness, respectability, and appearance of the counterpart’s demands and concessions (Pietroni et al. 2007). Furthermore, emotional expressions influence the counterpart’s perception of the other’s priorities, which in turn results in an adaptation of the pursued negotiation strategy (Pietroni et al. 2008). Specifically, whereas expressing happiness about the counterpart’s high priority issue and anger about the low-priority issue reduces fixed-pie perceptions and increases integrative strategies, the opposite emotional pattern amplifies the bias and reduces integrative behavior. The primer informs the counterpart about the possibility that her own high priority issue may be the other’s low-priority issue. This information allows for making more differentiated demands and concessions in order to increase the negotiation pie. Conversely, expressing anger about the counterpart’s high priority issue conveys the information that both parties value the same issue the most, resulting in zero-sum bargaining.

Only a few studies have directly assessed emotional contagion or reciprocity in e-negotiations. However, existing research indicates that this phenomenon also occurs in electronically mediated negotiation contexts. Indirect evidence stems from linguistic analyses showing that negotiators tend to reciprocate language and linguistic styles (Taylor and Thomas 2008). Furthermore, individuals are able to detect their partners’ emotions, and negative emotional states tend to spill over from one interaction partner to the other when communicating synchronously via EMC (Hancock et al. 2008). Consequently, emotional contagion does not only take place when nonverbal cues such as facial expressions are possible but also occur in a cue-impoverished environment. Thus, also in e-negotiations, negotiators have the tendency to mimic the counterpart’s text-based emotional expressions. Further research in this area shows that in asynchronous group negotiations via e-mail only one individual’s emotional expressions are sufficient to increase positive or negative emotions of the other team members (Cheshin et al. 2011). As previously pointed out, strong and negatively valenced emotions such as anger are more likely to be contagious or reciprocated and, in consequence, may trigger a downward spiral of negative affect more easily. Similarly, in online auctions a single negative comment plays a more important role than many positive comments (Nielek et al. 2010). Furthermore, also in online auctions there is evidence for the reciprocation of negative affect and the emergence of a downward spiral as dominant pattern. Similarly, Friedman et al. (2004) showed that expressions of anger in online mediations trigger an angry response by the counterpart which, in turn, lowers the likelihood of resolving the conflict. Congruous with literature on response-in-kind behavior in negotiations (Olekalns and Weingart 2003; Weingart and Olekalns 2004; Adair and Brett 2005), emotional action–reaction sequences are not limited to reciprocation, a reinforcement of the ongoing emotional patterns, but also include complementary and structural sequences. In negotiations the expression of embarrassment, regret, or guilt after having violated a social norm may evoke the complementary emotion of forgiveness in the counterpart (Keltner et al. 1997; Van Kleef et al. 2010). Similarly, negotiators may also mismatch each other’s affective expression by, for instance, countering anger with happiness. Displaying such complementary or structural emotions can aid negotiators to restore their relationship (Keltner et al. 1997; Van Kleef et al. 2010) and are vital for breaking negative cycles of reciprocity in negotiations (Brett et al. 1998). However, anti-complementary emotional pairs such as countering regret with anger may trigger a negative emotional dynamic and are detrimental for the maintenance of the relationship (Butt et al. 2005).

Overall, these studies provide evidence that major carriers of emotions such as facial expressions or intonation are not required to evoke similar emotions in the counterpart. Therefore, emotional contagion and reciprocity including their potential positive and negative consequences are phenomena that have also to be taken into consideration when negotiating online, even in asynchronous, text-based settings. Furthermore, the studies provide strong support that also in e-negotiations emotions coordinate the social interaction by providing information to the counterpart and act as an incentive or deterrent. However, these studies have primarily considered the deliberate and explicit use of emotional language and words. Other, more subtle ways of conveying emotions that are specific to a communication channel, as described in Sect. “Conveying Emotional Cues in e-Negotiations”, are less researched. Only a limited number of studies have specifically addressed how emotions are implicitly conveyed in e-negotiations and how they shape the negotiation process and outcome. Research by Sokalova and colleagues (Sokolova et al. 2004; Sokolova and Szpakowicz 2006, 2007) showed that language patterns such as immediacy are valuable indicators for discriminating successful and unsuccessful e-negotiations. For instance, they found that “you” corresponds to politeness in e-negotiations in which an agreement was reached and to aggressiveness in failed e-negotiations. They also showed that “I can accept” appears three times more often in successful than in unsuccessful negotiations, whereas “you accept my” is used twice as often in unsuccessful than in successful negotiations. Similarly, Griessmair and Koeszegi (2009) investigated the emotional connotation of messages exchanged in e-negotiations as well as different formulations of logrolling statements. Although trade-offs and logrolling are the primary means for increasing joint outcome and a hallmark of integrative bargaining, the authors show that their effectiveness depends on the wording. For instance, whereas “If we both could agree on [issue Y], we would be able to accept [issue X]” is formulated as potential acceptance with a request, “We cannot accept [issue X] unless we get [issue Y] in turn” employs conditional language combined with a rejection to express the same factual content. A commanding tone or conditional language such as “you accept my” or “unless we get” is associated with attacking face (Brett et al. 2007) (see Chap. 4 in this volume) and a negative emotional undertone (Schroth et al. 2005). Finally, the aforementioned study by Cheshin et al. (2011), investigating emotional contagion in e-negotiations, also addressed the relation between factual content and conveyed emotions. Whereas communicating flexibility was found to be associated with happiness, expressing resoluteness, not giving in, and acting tough were found to be perceived as displays of anger. Furthermore, when the behavior and the emotion communicated via text were incongruent (e.g., the words are pleasant but the behavior is uncompromising), negative emotions were found to be elicited in the other team members.

Emotions and Cognitive Processes: Intra-Personal Effects

Whereas the previous section addresses the effects of expressed emotions on the counterpart, the current section is concerned with the effects of emotions on the individual who actually experiences them. Research in the tradition of this so-called affect-cognition approach shows that emotions are inextricably linked with cognitive information processing. Hence, emotions “color” cognitive processes and influence an individual’s experiences, perceptions, and subsequent behaviors (Morris and Keltner 2000) (see Chaps. 1 and 2 in this volume). This assumption is discussed subsequently by addressing the questions of how emotions are tied to a negotiator’s memory and judgments, how emotions provide intra-individual information functions, and whether cognitive processes and information processing are dependent on the type of perceived and experienced emotions. A number of theories provide an explanation of how emotions and cognitive processes are interrelated. Martinovski and Mao (2009), for example, discuss several theoretical contributions that influenced advancements of research in this field such as appraisal theory (e.g., Smith and Ellsworth 1985; Lazarus and Smith 1988; Scherer 1999) or Theory of Mind (Martinovski and Marsella 2005; Martinovski 2010) (see Chap. 6 in this volume). The present discussion puts a stronger focus on other theoretical concepts that are more closely tied to the affect-cognition perspective, in particular Bower’s Semantic-Network Theory (Bower 1981), the Mood as Information Model (Schwarz and Clore 1983), and the Affect Infusion Model (Forgas 1995).

The interconnection of emotions and memory is addressed by Bower’s Semantic-Network Theory (Bower 1981). The theory proposes that the judgment of the current situation occurs within a network of semantic and emotional memories. Thus, current information, experiences, or events are also judged on the basis of their emotional similarity to past situations. Hence, related memories (of related situations) that were stored in memory under similar emotional conditions are argued to have a strong impact on the interpretation of the current situation. Similarly, the somatic marker hypothesis postulates that the assessment of decision-making tasks, and hence the process of decision making itself, is influenced by past events that took place under comparable emotional conditions (Damasio 1994). For example, repeated negotiations with the same counterpart may induce positive emotions if past negotiation encounters with her were satisfactory or pleasant. In addition, emotionally rich information tends to be remembered and recalled more easily than more fact-based information. Hence, if negotiators express strong anger or happiness regarding an issue under negotiation, the opponent may be more attentive to this issue and attach more value to it. This also means that it will be recalled more easily in the remainder of the negotiation process. Thus, emotions tend to have an important impact on information recall, learning, and situational interpretations (Forgas and George 2001).

Moreover, according to the mood-as-information model, a negotiator’s judgments are contingent on mood as intra-individual information (Schwarz and Clore 1983; Schwarz 1990, 2000). In particular, it states that negotiators use emotions that they experience or perceive to evaluate the current situation (Schwarz and Clore 1983; Schwarz 1990). Whereas positive emotions favor a positive situational interpretation, the opposite holds true for negative emotions (Keltner and Haidt 1999). For example, if negotiators are happy or pleased, they tend to perceive their environment as more positive and judge the information or offer that they receive from their counterpart in a more favorable way. In addition, also anticipated future emotional experiences or perceptions are believed to be judged and used in terms of their informational value when evaluating current situations and making decisions (Schwarz 2000). For example, when a potential agreement seems out of reach for the negotiators, they transfer their future unhappiness or anger to the current situation and judge it in a more negative light. An expected concession as reaction to a negotiator’s own concession, on the other hand, may result in a more positive judgment of the current situation as a result of the anticipated happiness. The affect infusion model (AIM; Forgas 1995) incorporates the theories outlined above and additionally addresses when emotions are a more or less important source for decision making: The more motivated negotiators are to invest cognitive resources in a willful search for, interpretation of, and use of information, the more they may be induced to become deliberatively attentive to emotional perceptions, experiences, or information. Similarly, the EASI model (Van Kleef et al. 2010b) posits that the way individuals cognitively process emotions and subsequently act depends on their epistemic motivation, i.e., their willingness “to develop and maintain a rich and accurate understanding of the world” (Van Kleef et al. 2004b, p. 511).

Several studies confirm the relationship between affect and cognition as well as its effect on subsequent negotiation behavior. Positive emotions can, for example, increase negotiators’ confidence and optimism, as well as impact their performance evaluation of the negotiation process and outcome (Kramer et al. 1993). Furthermore, negotiators in an emotionally positive condition may set higher negotiation goals (Baron 1990) and may have higher negotiation expectations (Yifeng et al. 2008). In contrast, intra-individual anger induces more dominating behaviors (Butt et al. 2005). Negative emotions may, however, also bias a negotiator in a positive way. Experienced negative emotions can increase negotiators’ awareness about their own violations of social norms and can motivate negotiators to change their course of thinking and their subsequent behaviors (Forgas 1998). Moreover, negotiators with low epistemic motivation tend to relate the counterpart’s expression of anger to the person rather than the task. This is not the case for negotiators with high epistemic motivation because they assess the displayed emotions more carefully and consider their deeper implications (Van Kleef et al. 2010a). Similarly, in the context of EMC, positive emotions result in more integrative bargaining (Carnevale 2008), and anger leads to more distributive positioning and competition. A direct test of affect infusion and epistemic motivation is provided by a study showing that negotiators were only affected by their counterparts’ expressed emotions when they were able and motivated to consider them—when they had a low (vs. high) need for cognitive closure, were under low (vs. high) time pressure, and had low (vs. high) power (Van Kleef et al. 2004b).

The Interplay of Affect and Cognition in e-Negotiations

Cognitive resources play a central role for the experience, perception, and communication of emotions (Blascovich 1992). The global cognitive capacity that individuals possess is used to assess or judge internal as well as external stimuli (Feldman 1995). Thus, the less attention individuals (need to) pay to external stimuli (e.g., to search for information, or to formulate trade-offs), the more they can devote to internal stimuli (e.g., to judge offers, behaviors, and emotions, or to think about and use emotions more willfully). Consequently, if eNS provide a less cognitively demanding environment, the supported negotiators may redeploy more cognitive resources to intra-individual processes and activities. In line with channel expansion theory (Carlson and Zmud 1999), eNS may thus also be regarded as tools that enable negotiators to expand or enrich the limited set of communication cues that are available to them in lower-bandwidth communication environments. When viewed in the light of emotion regulation literature (e.g., Richards and Gross 2000; Ochsner et al. 2002; Côté 2005; Wadlinger and Isaacowitz 2011), eNS may then mitigate more uninhibited and extreme emotions, or enable negotiators to (better) focus their attention on specific aspects of the negotiation problem or process. Importantly, while literature on emotion regulation argues that the deployment of cognitive resources to certain activities, and hence the regulation of emotions, can be learned, a provision of decision support would mean that the regulation of emotions can also be supported by an eNS. Consequently, the use of an eNS and a decision support component reducing the cognitive load for the negotiator may increase the negotiators’ ability to regulate (e.g., suppress or amplify) emotions more willfully. Providing negotiators with decision support may thus increase their “epistemic ability”, i.e., their ability to increase their epistemic motivation, which then influences the way negotiators (can) cognitively deal with and use emotions. In the following we elaborate on the mediating effects of eNS on emotions by distinguishing between two potentially different (and opposing) cognitive settings: situations of higher cognitive complexity and situations of lower cognitive complexity.

e-Negotiations and Emotions in Settings of High Cognitive Complexity

Whenever e-negotiations are conducted via synchronous rather than asynchronous communication, and/or are not supported by a decision support component, negotiators need to invest more cognitive resources to deal with external stimuli. As a consequence, negotiators either increase their cognitive effort or focus their cognitive resources on certain activities while ignoring others and make use of mental shortcuts and heuristics. Empirical findings based on the media naturalness hypothesis (Kock 2005) showed that cognitive effort and communication ambiguity were higher in quasi-synchronous EMC than in f2f communication (Kock 2007). The EMC condition also led to a reduction in the fluency of communication and an increase in message encoding effort (Kock 2007). Investigations of flaming in instant-messaging negotiations (Johnson et al. 2008, 2009) show that negotiators who engage in flaming were less likely to reach an agreement and concluded that the intra-individual management (or regulation) of anger is important for the mitigation of flaming and its negative consequences. Johnson and Cooper (2009) further found that communication via instant-messaging was less emotionally positive than communication via telephone.

These results suggest that negotiators may be less cognitively able to control emotional processes or behaviors in environments of higher cognitive complexity and are also more influenced by their emotional experience (McKenna and Bargh 2000). As a result, negotiators may engage in more normatively inadequate, explicit, intense, or extreme (emotional) behaviors (Kiesler and Sproull 1992; Thompson and Nadler 2002; Friedman et al. 2004) than they would in situations of lower cognitive complexity. Moreover, Walther (1996) explicates that EMC environments can foster “hyperpersonal communication” (p. 17): When negotiators have a limited amount of social information at their disposal, they tend to consider these information in their judgments more than actually warranted and make “overattributions”. Accordingly, if negotiators focus their attention and cognitive resources on specific issues, they may regard and interpret these issues as more important than others. Negotiators also rely more strongly on these issues when making inferences about the situation and the counterpart as well as when taking subsequent actions. For example, if a negotiator’s counterpart uses a dominating language style, and the focal negotiator’s attention is drawn to this piece of information, then she might overattribute this input and judge the opponent as angry or aggressive, even if the opponent’s offers are fair and generous.

e-Negotiations and Emotions in Settings of Low Cognitive Complexity

Whenever e-negotiations are conducted via asynchronous rather than synchronous communication and/or are supported by a DSS, negotiators need to invest less cognitive resources to deal with external stimuli. As a consequence, eNS may help to reduce a negotiator’s cognitive effort, or, put differently, an eNS may help to increase negotiators’ ownership of their cognitive resources (Silver 1988; Singh and Ginzberg 1996; Foroughi 1998; Weber et al. 2006; Kersten and Lai 2007). Research comparing asynchronous e-mail and synchronous f2f negotiations (Morris et al. 2002) finds rapport building via emotional disclosures is more difficult to achieve with e-mail communication. If e-mail negotiators, however, talk to each other over the phone prior to the start of the negotiation, the negotiators managed to build more or a better rapport. A comparison of instant-messaging and e-mail negotiations shows that, due to the higher interaction speed and reduced information processing time, negotiators use more dominating communications when interacting via instant-messages (Loewenstein et al. 2005). Similarly, Pesendorfer and Koeszegi (2006) show that negotiators interacting via a synchronous communication channel engage in more affective, disinhibited, and competitive behaviors, than negotiators who interacted with each other asynchronously. Their results suggest that, because negotiators interacting in an asynchronous manner have more time to act and react, they also have time to cool down and reflect. Since cooling down and reflecting are related to the possibility of partitioning cognitive resources over a longer time period, these results also indicate that, when negotiating asynchronously, negotiators are better able to regulate their emotions. In other words, supplying e-negotiators with more time to (re)act can increase their epistemic ability.

Only limited empirical evidence is available on the impact of decision support on affect-cognition in e-negotiations. Koeszegi et al. (2006), for example, provide such evidence for text-based asynchronous e-negotiations. While negotiators, independent of their use of analytic decision support, express a similar relative frequency of negative emotions, negotiators express more positive emotions in task-related as well as private communication. Similarly, the use of an analytic decision support component in asynchronous negotiations is found to increase the absolute amount of expressed thought units in negotiations (Schoop et al. 2014). However, in contrast to the prior study, negotiators provided with decision support show more negative emotions than negotiators not provided with decision support. While the results of these two studies may seem at odds with each other, it is worth pointing out that in the latter study negotiators were provided with a more sophisticated communication support technology giving negotiators more control and understanding about their communication. As a consequence, negotiators may have been less cognitively taxed and thus better able to use negative emotions more willfully in line with their signaling functions.

The Interplay Between Social Functions and Affect-Cognition in e-Negotiations

Although we discussed intra- and inter-personal effects of emotions separately, affect-cognition and social functions of emotions are inextricably interwoven and have to be considered in conjunction to fully grasp the impact of emotions in e-negotiations. As depicted in Fig. 5.2, the behavior of negotiator A and the emotions she conveys when setting the behavior causes a cognitive evaluation by negotiator B. The cognitive evaluation does not only trigger an emotional experience but is also influenced by the current emotional state of the negotiator. This, in turn, will determine the behavior with corresponding emotional expressions that negotiator B shows in response to negotiator A’s first move. Negotiator B’s behavioral–emotional reaction serves as input for negotiator A’s cognitive-emotional evaluation triggering her reaction. This cognitive-emotional fugue (Lewis et al. 1984) performed during the ongoing interaction shapes the dynamic of the negotiation and its outcome.

Fairness in negotiations can be used to exemplify Fig. 5.2 and the complex interrelations between affect and cognition and the social functions of emotions. Fairness evaluations have long been thought as purely cognitive process; however, a number of authors argue that fairness can be thought of as an affective event and that cognitive fairness evaluations are only performed after fairness-related emotions have been experienced (Solomon 1989; Weiss and Cropanzano 1996; Weiss et al. 1999). Furthermore, following appraisal theories of emotions (Frijda 1986; Lazarus 1991), the emergence of emotions in negotiations is primarily related to the progress individuals make toward achieving their goals (Kumar 1997; Fischer and Van Kleef 2010; Van Kleef et al. 2010b). If negotiator A, for example, makes an unfair offer while conveying positive emotions, this behavioral–emotional information constitutes the input for negotiator B’s cognitive-emotional evaluation. The unfair offer and the resulting goal frustration are likely to trigger feelings of anger in negotiator B (Hegtvedt and Killian 1999; Weiss et al. 1999; Barclay et al. 2005). Also, the incongruence between communicated emotion and actual behavior by combining an unfair offer with the display of positive emotions might further exacerbate negotiator B’s experienced negative emotions (Cheshin et al. 2011). Furthermore, if negotiator B is already in a negative emotional state as a result from previous interaction steps, she is likely to scrutinize the offer in more depth and evaluate it even more negatively (Staw and Barsade 1993). This cognitive-emotional evaluation determines negotiator B’s subsequent behavior and emotional expression. Thus, negotiator B is likely to respond in kind to the unfair offer and display anger. The anger displayed by negotiator B has an important informational function for negotiator A and signals that the previous behavior was unacceptable and that a change of the course of action is required in order to reach an agreement (Morris and Keltner 2000). If negotiator A chooses to respond to negotiator B’s expression of anger with guilt and a fairer offer, she signals that she is willing to make up for the transgression (Van Kleef et al. 2010b). Displaying guilt as complementary emotion to the previous expression of anger introduces a structural sequence (Adair and Brett 2005; Van Kleef et al. 2010b) which can aid the negotiators to re-introduce a constructive negotiation dynamic and restore their relationship (Keltner et al. 1997; Van Kleef et al. 2010b). Conversely, if negotiator A would have responded in kind by reacting to anger with anger, a conflict spiral of negative emotional dynamics, resulting in an impasse, might have been triggered (Brett et al. 1998).

The example shows how affect-cognition and social functions work together in shaping the negotiation process and outcome. However, the described effects are further mediated by the negotiation context. The EASI model (Van Kleef et al. 2010b) also provides a comprehensive rational for the different effects emotions have in social interactions. Accordingly, the specific social functional effects of positive and negative emotions depend on whether the negotiation setting is competitive or cooperative. In a competitive context, the display of anger in the aforementioned example is more likely to induce the counterpart to react with more cooperative behavior and make concessions as it signals that limits are reached and the willingness to retaliate or terminate the negotiation. Conversely, in a cooperative setting the same emotional display is more likely to reduce cooperative behavior as it conveys adverse signals and elicits similar emotions in the counterpart. Negotiating via EMC or employing a DSS is yet another context factor influencing the cognitive-emotional fugue as well as how and to what extent emotions have beneficial or detrimental social functions in negotiation interactions (see Fig. 5.3).

Research addressing the impacts of e-negotiation contexts on the inter-personal social functions of emotions as well as on intra-personal affect and cognition, as depicted in Fig. 5.3, is rather limited from a joint perspective. Thus, to illustrate the potential influence the communication and decision support components of an eNS can have on emotions in e-negotiations, we subsequently extend the example given above. For instance, negotiator B in the previous example might have e-mailed “Your previous offer makes me angry!” as response to negotiator A’s unfair offer. By doing so she communicates a direct emotional signal that a change of action is required. However, she might also have replied with “Your offer is simply unacceptable!!!” employing the grammatical marker “!!!” and a specific language choice to implicitly convey feelings of anger via such emotext or “electronic paralanguage.” Yet, the lower the bandwidth of a communication channel in terms of lacking primary carriers of emotions such as facial expressions, the more important become alternative and more subtle ways of conveying emotions. The efficiency and clarity with which negotiators can convey and understand emotions transmitted via an electronic channel determines whether and to what degree emotions can fulfill their vital functions in coordinating the interaction in e-negotiations. For instance, negotiator B intended to signal her anger with “Your offer is simply unacceptable!!!”; however, negotiator A might not have been able to decode the emotional language correctly because the negotiators have yet not been able to establish a common emotional code in the electronic environment. Negotiator B has introduced ambiguity by expressing her emotions with electronic paralanguage and negotiator A was not capable of deriving the emotional meaning of the messages. As a result, the conveyed emotion did not fulfill its informational function and negotiator A might not have responded with a fairer offer and regret in order to restore the relationship and re-introduce a constructive negotiation dynamic. Thus, with respect to the second message, the eNS may make a difference regarding its interpretation. If we, for example, assume that the negotiators interact via a synchronous text-based communication channel and have no DSS available, the eNS is rather cognitively demanding, which means that negotiators may (implicitly) partition their cognitive resources to certain activities. As a consequence, the second exemplary message may only be interpreted with a focus on the fact-based content, i.e., that the offer is unacceptable, which could leave the negotiator to conclude that this message is rather emotionally neutral. In this case, a negotiator would not be cognitively able, or willing, to deploy enough cognitive resources to read or judge the subtle undertone supplied by the grammatical marker “!!!”. Another message that illustrates this issue would be “Your previous offer makes me angry!;).” If negotiators would be highly cognitively taxed by the context, i.e., the usage of the eNS, then they may overlook the appended emoticon “;)”, which implies that this message should not be considered as angry. As such, the potential of negotiators to decode a message as intended by its encoder depends on the cognitive resources that negotiators can deploy for this activity, and thus on the cognitive complexity of the current situation, which is shaped or enacted by the eNS.

Although research has established strong evidence on the interplay between emotion, cognition, and information processing (Bower 1981; Forgas 1995, 1998; Schwarz 2000), the impact of e-negotiations on this relationship is still not fully explored. For instance, when conducting an e-negotiation via chat (synchronous) and without decision support, negotiator A has only limited time and cognitive information processing capabilities at her disposal to decode and evaluate the angry response by negotiator B and formulate a reply. As a result, she might not be able to fully digest the arguments and the intention of the message both on a socio-emotional and on a fact-oriented level (Friedman and Currall 2003; Loewenstein et al. 2005). In particular when she blames negotiator B (Weiss et al. 1999; Barclay et al. 2005) and is in a state of high negative arousal in reaction to B’s message (Barsade 2002; Friedman et al. 2004; Van Kleef et al. 2004a), negotiator A is likely to act less rationally, react with anger, and consolidate the conflict spiral (Brett et al. 1998; Friedman and Currall 2003). Thus, the negative emotions negotiator A experiences on an intra-personal level are likely to infuse her inter-personal behaviors toward negotiator B (Forgas 1995). If the negotiators would be supplied with decision support and negotiate asynchronously, they would be able to process information more accurately (Swaab et al. 2004; Kersten and Lai 2007) and may avoid irrational behavior and cognitive biases (Anson and Jelassi 1990; Foroughi 1998), since cognitive resources would be freed up (Blascovich 1992; Feldman 1995), and negotiators would have more time to cool down (Friedman and Currall 2003; Pesendorfer and Koeszegi 2006). Thus, by having a decision component available that provides a utility assessment of the exchanged offers, negotiator A may be able to consider B’s offer in its entirety, rather than using the salient emotional content of negotiator B’s message as central information, to evaluate the offer and understand it accordingly. In doing so, the decision support helps to bring the negotiation back to a rational basis and reduce the detrimental effects of emotional biases (Foroughi 1998). By reducing the cognitive effort required by negotiator A to analyze the factual content of the offer, more cognitive resources can be devoted to judge the emotional meaning of the message and formulate a response that is backed by arguments. Finally, decision support would help negotiator A to identify possible trade-offs and craft a mutually beneficial counteroffer (Kersten and Lai 2007) without provoking further negative emotional reactions by negotiator A. Negotiating asynchronously would moreover give negotiator A the time to cool down and avoid being in a state of negative emotional arousal when formulating the reply (Friedman and Currall 2003; Pesendorfer and Koeszegi 2006). Furthermore, she would have the possibility to review the negotiation protocol in order to identify what led up to the critical moment and review her message in order to formulate a reply that redirects the negotiation to positive grounds (Friedman and Currall 2003).

Conclusion and Outlook

Our review shows that emotions play a very important role in e-negotiations. However, an accurate understanding of the role of emotions in e-negotiations is only beginning to emerge. We add important aspects to the current understanding of emotions in e-negotiations by highlighting that the characteristics and functionalities of e-negotiations and eNS are interconnected with emotions. Research in line with the cues filtered-in perspective shows that emotions are a central part of electronic communication and that emotions are not mitigated but may even be intensified in EMC. In this respect, the social functions of emotions should be considered as important driving forces in and throughout e-negotiation processes. Besides being important at the inter-personal level, emotions are also central factors of influence at the intra-personal level. In line with that, we point out that the cognitive complexity of the negotiation situation, which is enacted and defined by the eNS, has an impact on the negotiators’ abilities to encode and decode, or understand and communicate, emotions properly and as intended.

The integration of socio-emotional and rational-economic factors is an emerging field in various disciplines and the knowledge gained can be employed for developing and improving eNS. For instance, Brams (see Chap. 7 in this volume) and Loewenstein (2000) show how emotions can be incorporated in game theoretical approaches and the construction of utility functions, respectively—both are cornerstones of the decision support component of eNS. Similarly, the emerging field of “soft” or Behavioral OR considers socio-emotional aspects in the modeling of decision problems in order to help individuals, groups, and organizations to make and take decisions (cf. Hämäläinen et al. 2013). Recent research in the area of eNS also calls for the need to consider the higher level economic and behavioral goals of all parties involved in negotiations including such aspects as emotions (Vetschera et al. 2013). Initial empirical results directly comparing economic and behavioral support indeed show that effects of both support approaches are not limited to the respective support dimension, but actually show several spillovers (Gettinger et al. 2012a). Furthermore, advances in the fields of automated emotion recognition from text (e.g., Kramer et al. 2014) and facial expressions (e.g., Bailenson et al. 2008) can also be fruitfully used in designing socio-emotionally oriented eNS.

So far, only few attempts have been made to directly integrate such aspects and develop more behaviorally oriented eNS. One example is the Graph Model for Conflict Resolution implemented in the DSS GMCR II supporting decision makers and negotiators in strategic conflicts (Hipel et al. 1997). While originally rooted in metagame theory, the paradigm of the Graph Model for Conflict Resolution was later extended to consider emotions (Obeidi et al. 2005). This extension shows that experienced positive emotions augment the set of potential states and therefore recognized actions and alternatives considered by the parties. Experienced negative emotions, on the other hand, restrict the set of possible actions and alternatives.

Alternatively, Broekens et al. (2010) suggested an “affective” eNS that is designed to aid negotiators in managing their own emotions, comprehending and reacting to the emotions expressed by their counterpart adequately, and guiding negotiators in using emotions strategically. The authors also suggest affective support tailored to different negotiation phases. For the preparation phase, they propose to transfer concepts of analytic support approaches to emotional dimensions. Similar to the way preferences regarding issues are elicited and utility values are assigned to issues and issue values, negotiators may also link emotions to specific issues and issue values. Furthermore, negotiators might even want to explicitly state emotional goals for upcoming negotiations including the relative importance of experiencing or not experiencing specific emotions. In the actual conduct phase, an affective eNS could detect prevalent emotions and make negotiators aware of them and their possible consequences. Furthermore, such an affective eNS may also give suggestions and recommendations on how to handle the current emotional state. Moreover, affective eNS could also give advice on when and which emotions should be expressed to gain a strategic advantage in line with the signaling functions of emotions (Morris and Keltner 2000; Van Kleef et al. 2010b). Such affective eNS could provide feedback about prevalent emotions, or proactively intervene in the process by making suggestions and recommendations

Furthermore, affective eNS could be used for novice or expert training, as well as to prepare for specific negotiations. In such an “emotional training”, negotiators could be confronted with counterparts differing in their emotional reactions or offer-related behavior during negotiations. By reviewing and analyzing the negotiation afterwards, trainees receive important feedback about their interactions with emotional patterns. eNS may even be used for emotional training without direct human counterparts, which reduces the costs for human capital. eNS could use predefined sentences or entire text messages transmitting and communicating specific emotions, as is already done for research purposes (Van Kleef et al. 2004a; e.g., Van Kleef et al. 2004b, 2010a). Related research already shows that virtual negotiators are able to express emotions via facial expressions that are correctly interpreted by their human counterparts (e.g., Qu et al. 2013, 2014). An (emotional) training in such a virtual reality has also been found to increase negotiation knowledge and conversation skills (Broekens et al. 2012) and thus seems to be a promising avenue for educational purposes and the “emotional professionalization” of negotiators.