Abstract

Past research has documented that both attachment (in)security and the quality of friendship play critical roles in life satisfaction (LS). This study aims to delineate the interplay between the fundamental attachment dimensions (i.e., anxious and avoidant attachment to mothers) and friendship (i.e., friendship quality and conflict) on LS by testing three plausible expectations. First, the unique predictive power of the attachment dimensions, friendship quality, and conflict on LS was examined. Second, moderating and third mediating effects of friendship quality and conflict on the link between the two attachment dimensions and LS were investigated. Children (N = 357) attending 5th to 8th grades in Ankara, Turkey completed the measures of LS, anxious and avoidant attachment to mother, and friendship quality. Results indicated that both attachment dimensions among girls and attachment avoidance only among boys predicted LF. Friendship quality was the unique predictor of LS for both sexes above and beyond effects of attachment dimensions. Friendship quality also moderated the effect of attachment avoidance on LS among girls and mediated the effect of attachment avoidance among boys. Findings suggested that avoidant attachment to mother and low level of friendship quality are the risk factors during middle childhood for life dissatisfaction in the Turkish cultural context.

The Interplay between Attachment to Mother and Friendship Quality in Predicting Life Satisfaction among Turkish Children

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Life satisfaction (LS) as an integral part of well-being (Diener 1984) helps adaptation for survival by promoting the psychological conditions for exploration, personal and social development, and coping efficacy under stress (Diener and Diener 1996). Hence, psychologists, especially positive psychologists, have been trying to understand the fundamental predictors and the mechanisms that enhance LS in the last decades (see, Diener et al. 1999; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005).

A recently published extensive comparative study conducted in 29 rich countries by UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Fund) on child well-being during middle childhood revealed that the child’s sense of subjective well-being and life satisfaction go hand in hand and both are deeply bound up with the quality of relationships with parents and peers (UNICEF Office of Research, Innocenti Report Card 11, 2013). Their findings showed that if children found it easy to talk to their mothers and fathers, they also found their classmates kind and helpful in the majority of the countries. The link between the quality of parental and peer relationships is the strongest among those countries where children have highest level of both objective wellbeing (e.g., in material, health, education, housing, and environment domains) and subjective well-being. Reporters concluded that “…family relationships are the single most important contributor to children’s subjective well-being…and relationships with peers can play an important role in both day-to-day well-being and long-term developmental progress” (p. 40).

The UNICEF survey and other similar research, indeed, confirms the basic tenet of attachment theory (Bowlby 1969, 1973; Cassidy 2008) asserting that the quality of early interactions within the family impacts child’s competence in social and personal domains, especially by guiding his/her quality of relationships with peers later in life. Later studies largely supported the assertion that the quality of parent and peer relationships are strongly related, and in turn, both contribute to LS via enhancing happiness and subjective well-being among children and adolescents (see Demir et al. 2013; Gilman and Huebner 2003; Mikulincer and Shaver 2013).

Although there exists an extensive literature on the interplay between attachment security to parents and child’s relationship quality (see Kerns 2008), especially with the peers and friends (see Ladd 1999; Schneider et al. 2001) and between attachment to parents and peers (see Gorrese and Ruggieri 2012; Kerns 2008), almost no study has specifically examined the effects of anxious and avoidant attachment to parents together with the quality of friendship on happiness and LS in middle childhood. Furthermore, there exists scarce data from the non-Western cultures regarding the effect of attachment (in)security on social competence and LS. Therefore, considering that individual differences in attachment can be most parsimoniously captured along the two fundamental dimensions representing attachment-related anxiety and avoidance (Brennan et al. 1998; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007), the current study has primarily aimed to examine the effects of anxious and avoidant attachment to mothers and the quality of friendship on LS in middle childhood in the Turkish cultural context.

Attachment Perspective

According to Bowlby (1973), children develop internal working models (mental representations) of themselves as being worthy (or unworthy) of love and care, and others, especially attachment figures, as trustworthy and responsive (or untrustworthy and unresponsive) on the basis of the quality of their early interactions. These mental representations guide belief, expectations, and behaviors in all sorts of close relationships including friendships across the life-span (Kerns 2008). Depending on the positivity or negativity of these mental models, individuals use different emotion and behavior regulation and coping strategies to deal with the relationship problems. With the contribution of Mary Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al. 1978) and other attachment researchers, especially following Hazan and Shaver’s (1987) seminal work on adult romantic attachment, attachment theory has been expanded and utilized as a general framework in understanding the dynamics of close relationships including peer relations and friendships and resulting impact on psychological well-being (see Mikulincer and Shaver 2007).

Initially, Ainsworth et al. (1978) systematized attachment theory to better understand the individual differences in the internal working models reflected in the (in)security of attachment bond. These researchers have shown that maternal sensitivity that provides a reassurance for proximity, a secure base for exploring the social and physical environment, and a safe haven to return when feeling stressed are the key factors in attachment security. If children’s needs for proximity, safety, and security are sufficiently and consistently met when they are distressed, they are more likely to develop a secure attachment orientation. Furthermore, using the caregivers as the secure base children effectively explore the social networks and can have the opportunity to practice their social skills with peers to develop multiple attachments to significant others later in life. However, if their primary caregivers are inconsistently responsive to their needs and intrusive, they may develop an insecure anxious-resistant attachment pattern. If the caregivers are consistently rejecting and emotionally unavailable, then they are more likely to develop an insecure avoidant attachment.

Attachment theory has become one of the leading theoretical frameworks in understanding underlying dynamics in close relationships during the last three decades. Accumulation of attachment studies has shown that individual differences in attachment orientations and their underlying internal working models can indeed be best represented in the two fundamental dimensions reflecting attachment-related anxiety and avoidance which are relatively stable from early years to adulthood (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). Similar to the dynamics in the early years, attachment anxiety reflects worries in close relationships, a strong need for closeness, and fear of being abandoned. Attachment avoidance, however, reflects an extreme self-reliance and emotional distance from close relationships. From a developmental perspective, children who are anxiously attached to primary caregivers or peers probably have the early experiences of physical and/or emotional abandonment. Thus, they usually exaggerate their distress and fears by asking for constant help, seeking for closeness, and clinging to their friends and partners to stave off abandonment, and constantly challenged by their negative emotions that reduce their happiness and well-being. Specifically, using a hyperactivating emotion and behavior-regulation strategy, those who are anxiously attached to their caregivers heighten their distress, anger, and dependency to force the attachment figures to respond to their demands. Hence, they are also extremely hyper-vigilant, prone to conflict, distressed in friendship, and experience negative emotions.

By contrary, probably because of their early rejection experiences, children who have an avoidant attachment to their caregivers use deactivating emotion and behavior-regulation strategy that bases on extreme self-reliance, repression (or defensive exclusion) of negative affect, such as sadness, need for closeness and dependency. Thus, they try to avoid a possible rejection from attachment figures and peers by maintaining psychological, social and emotional distance, and independence at the expense of close peer relationship (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). Meta-analyses have shown that, females have higher attachment anxiety and lower attachment avoidance than males in Western cultures (Del Giudice 2011).

Confirming these theoretical accounts, past studies have shown that attachment security to parents constitutes an important personal resource that promotes exploration in personal domains and competence in friendship especially during middle childhood (Kerns 2008) as well as it enhances positive emotions and happiness (Mikulincer and Shaver 2013).

Attachment, Social Competence and Life Satisfaction in Middle Childhood

Previous studies have provided abundant evidence showing that early parent-child interactions are closely associated with the quality and competence in friendship and subjective well-being. Although both the pattern and the dynamic of attachment relationship between parents and children relatively change during middle childhood, the studies focusing on the link between attachment security, friendship quality, and LS in this developmental period is relatively rare (Kerns 2008; Kerns et al. 2006; Mayseless 2005). The importance of peers becomes evident and children spend relatively more time with their peers in middle childhood. Although children still see their parents as the primary attachment figures, their expression of attachment needs changes from more proximal behaviors to symbolic ones due to transformations in cognitive and emotional development in this stage (Kerns 2008, Kerns et al. 2006).

In an earlier study, Kerns et al. (1996) found that children having secure attachment to their mothers were more reciprocated and accepted by their peers, more responsive to friendship, and more effective in regulating their emotions with peers than those having insecure attachment to their mothers. Lieberman et al. (1999) demonstrated that secure attachment to both mother and father was related to positive friendship qualities and lack of conflict in best friendships during middle childhood and early adolescence. They also found that the availability dimension of secure attachment to mother was the critical predictor of friendship quality and availability of fathers was the critical predictor of lower conflict with best friends. Moreover, previous studies have also documented that the children’s friendship is closely associated with their well-being and LS. Friendship quality seems be more important during middle childhood as compared to adolescence and adulthood periods since children do not have other sources of close relationships, such as romantic relations, they are under an increased pressure of school and family environment, having acceptance by peers is their prior goal (Gilman and Huebner 2003; Holder and Coleman “Children’s friendships and positive well-being”; Huebner and Diener 2008).

Marking the importance of early years, two recent longitudinal studies have provided evidence for the effects of attachment dimensions on social competence and friendship quality. Zayas et al. (2011) have shown that quality of maternal caregiving given at 18 months of age predicts how comfortable people are in relying on peers and partners, namely attachment avoidance, 20 years later. Similarly, Fraley et al. (2013) tracked a cohort of children and their parents from birth to age 15 using multiple measurements of attachment, social competence, and friendship, and found that early maternal sensitivity and parental attachment avoidance were the strongest predictors of best friendship quality.

Others studies have replicated the documented link between attachment to parents and dimensions of social competence including friendship quality (Kerns 2008). Schneider et al.’s (2001) meta-analysis including 63 studies (54 of them from North America) yielded a moderate effect size (0.20) of the association between attachment to mother and competence in peer relationships. The effect size increased to. 24 when the studies looking only at the association between parent-child attachment security and friendship quality were considered. However, both unique and overlapping contribution of attachment security and friendship quality to happiness and LS is still unknown. Moreover, majority of the past studies in middle childhood investigated attachment security or insecurity to parents without specifically examining if the two fundamental dimensions, attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, are distinctively associated with friendship quality and conflict, and in turn, if they predict LS.

Past studies on late adolescents and emerging adults have shown that both attachment anxiety and avoidance are negatively associated with friendship quality (e.g., Doumen et al. 2012; Özen et al. 2011). Both attachment dimensions and friendship quality have also been found to be systematically linked with happiness and LS (Demir et al. 2007; Demir et al. 2013, Mikulincer and Shaver 2013). Specifically, past work has demonstrated that, as one of the main developmental antecedents of positive emotions, happiness, and LS, attachment anxiety intensifies negative emotions, and thus, deteriorates feelings of LS; and attachment avoidance was shown to lead to defensive suppression of emotions iresulting in a blockage of experiencing positive emotions and LS (Mikulincer and Shaver 2013; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007). Similarly, the link between friendship quality and happiness representing LS has been well documented almost universally throughout the lifespan, ethnic groups, and various cultures (see Demir et al. 2013, Huebner and Diener 2008). Therefore, it is imperative to examine the unique and interactive effects of both attachment dimensions and friendship quality to LS in middle childhood.

In addition to friendship quality, conflicts between friends can be a source of unhappiness by reducing their well-being and increasing discordance within the friendship network (see Demir et al. 2013, Holder and Coleman “Children’s friendships and positive well-being”). Therefore, the power of friendship conflict, relative to friendship quality, in predicting LS should also be investigated.

Sex differences in peer relationships have been well-documented. For instance, decades of research have shown that friendships of girls when compared to boys are higher in intimacy and overall quality (Nangle et al. 2003; Oldenburg and Kerns 1997; Parker and Asher 1993; see Rose and Rudolph (2006) for a review). Thus, the impact of friendship experiences on emotional adjustment could be stronger among girls than boys (Oldenburg and Kerns 1997; Rose and Rudolph 2006); an argument extended to intimate relationships of adults (Saphire-Bernstein and Taylor 2013). Although research among young adults showed that friendship experiences are similarly related to happiness among men and women (Demir and Davidson 2013); Oldenburg and Kerns (1997) have shown that popularity was related to emotional adjustment among girls but not boys. Since this issue was not addressed among Turkish children, and in light of convincing theoretical arguments (Rose and Rudolph 2006), it is plausible to argue that the unique variance explained by the attachment and friendship variables in LS could be larger for girls than boys. Also, children’s interpersonal relationships, especially after the age of eight have been shown to be an important correlate of their life satisfaction (Huebner 2008). Thus, age of the child should be considered in testing the associations among these variables.

Previous studies investigating the effect of attachment security on friendship quality and subjective well-being have been mostly conducted in North American cultures. Furthermore, the majority of the previous studies utilized a secure vs. insecure split in their analyses and did not specially examine the effect of anxious and avoidant attachment to parents on friendship and LS. Although there exist studies using attachment classifications of children, as secure, avoidant and resistant (or ambivalent), and compared them on the given outcome variables, they did not distinguish between anxious and avoidant attachment to mothers as the continuous fundamental dimensions of attachment.

Only a few studies investigated the effect of attachment to parents and friendship quality on LS (e.g., Ma and Huebner 2008), well-being (e.g., Kankotan 2008) or overall psychological functioning (e.g., Rubin et al. 2004). Rubin et al. (2004) and Booth-LaForce et al. (2005) specifically examined whether perceived parental support (representing attachment security) and friendship quality predict global self-worth, internalizing and externalizing problems, and social competence in peer relationship in middle childhood. These studies have shown that parental support and friendship quality predicted lower level of rejection from friends and less victimization for girls only. They also found that parental support and friendship have both independent and interactive effects on psychological functioning including high global worth and less behavior problems. Although they did not directly assess well-being or LS, their findings imply that attachment security and friendship quality may have independent effects on LS.

These studies, however, did not specifically investigate if anxious or avoidant attachment to parents and friendship quality uniquely predict LS. Considering that attachment security and friendship quality are consistently correlated and these constructs, in turn, similarly correlate with happiness and LS with a range between r = 0.30 and 0.50 for almost all ages in previous studies (see Demir at al. 2013; Mikulincer and Shaver 2013), it is imperative to examine how much variance in LS can be accounted for by friendship quality beyond attachment (in)security. Furthermore, the potential mediating and/or moderating associations between the attachment dimensions and friendship quality have not been explored yet. Finally, the associations between attachment, friendship, and LS (or overall well-being) have been mostly studied among adolescents and adults, ignoring the middle childhood, in which children begin to establish stable friendships (Holder and Coleman “Children’s friendships and positive well-being”; Mayseless 2005).

Attachment in the Cultural Context

Past studies have shown that whereas attachment security is the optimal normative pattern in the majority of the cultures, both degree and the type of attachment insecurity vary greatly across cultures (Rothbaum et al. 2000; van IJzendoorn and Sagi 2008). Because of their varying cultural adaptive value, attachment anxiety in collectivist cultures and attachment avoidance in individualistic cultures seem to be more prevalent. In an initial meta-analysis on infant attachment classification, van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg (1988) found that although there was no cultural difference on secure classification, anxious-resistant category was relatively higher in collectivistic cultures, such as Japan, and avoidant category was common in Anglo-Saxon individualist cultures, such as Germany and Holland. Similar cultural variation was recently observed in the adult attachment classification. Using samples from 64 cultures from all continents, Schmitt et al. (2004) found that preoccupied romantic attachment, which is typified with high attachment anxiety and low avoidance, is particularly common in East Asian cultures and dismissing attachment,which is characterized by low attachment anxiety and high attachment avoidance, is common in Western cultures.

The degree of interpersonal distance that shapes the level of cohesion and harmony in close relationships in a given culture appears to be associated with the prevalence of attachment anxiety and avoidance. Rothbaum et al. (2002) argued that since extreme dependency, especially between the mother and child, is functional in cultures valuing closely knit relatedness, attachment anxiety (or anxious ambivalent attachment) should not be seen as abnormal or maladaptive. In contrast, since attachment avoidance may imply a complete independence, rejection or exclusion, it may be critically maladaptive in collectivist/relational cultures. Recently Friedman et al. (2010) systematizing these arguments using the “cultural fit hypothesis” suggesting that culturally incongruent pattern of attachment orientation would have stronger effects on relationship quality. Specifically, attachment avoidance in collectivist cultures and attachment anxiety in individualist cultures have relatively a stronger power in predicting relationship functioning.

Cultural differences in peer relationship and friendship dynamics indeed begin in early childhood with the caregivers’ socialization goals, believes, and expectations for children’s peer relationships, which in turn, reflect into the cultural scripts guiding the expectations from peers and friends across the life-span (Edwards et al. 2006; French et al. 2011). Consistently, because of the cultural value attached to friendship, its function in personal well-being may change across cultures (e.g., Demir et al. 2012). Attachment orientations are expected to influence and shape the dynamics of friendship functions as well as subjective well-being depending on the cultural congruence of the assessed attachment orientations, namely attachment anxiety or attachment avoidance. For instance, if cultural scripts in peer relationships are formed in terms of in-group solidarity, intimacy, and emotional interdependency, attachment avoidance can sharply contrast with the expectations from friends, and thus harms the quality of friendship in relational/collectivist cultures. However, if cultural scripts orient the children to expect intimacy as a not required attribute in friendship, and thus, see the friends as nonintimate acquaintances (see Triandis et al. 1988), attachment avoidance, relative to attachment anxiety, may not be a critical threat for friendship quality and LS in individualist cultures.

Turkish familial and in-group relationships are generally characterized by closely knit ties which are called by Kağıtçıbaşı (2005) as “psychological/emotional interdependence family model” referring a dialectical synthesis of both self-reliance and interpersonal harmony, rather than complete independence or interdependence within the family. Therefore, considering the divergent adaptiveness of attachment dimensions, Sümer and Kağıtçıbaşı (2010) argued that attachment avoidance of parents, especially mothers, would be more maladaptive than attachment anxiety, and thus, would be predictive of children’s attachment (in)security in collectivist/relational cultures. Supporting their expectation, they found that attachment avoidance of mothers, rather than their attachment anxiety, predicted negatively their children’s attachment security in middle childhood. Consistent with this finding, Selçuk et al. (2010) demonstrated that mothers’ attachment avoidance, but not attachment anxiety, predicted global maternal sensitivity observed in the daily interactions with their young children, even after controlling for the child’s temperament in Turkey.

Based on the above arguments and previous findings, it can be argued that attachment avoidance may not be very dysfunctional in the individualist cultures in which interpersonal boundaries are not unclear and individuals can make friends easily but with low emotional interdependence. However, it would be detrimental for friendship quality and LS in the relational cultures in which interpersonal boundaries are fuzzy and emotional closeness and interdependency are expected. Therefore, it can be expected that attachment avoidance relative to attachment anxiety would be strongly associated with LS as well as friendship quality in the relational/collectivist cultures, such as Turkey.

In conclusion, previous studies conducted in the Western cultures have mostly focused on the secure/insecure division and commonly implied that insecure attachment to parents deteriorate the quality of relationships with friends and creates a risk for LS. However, they have left unexamined whether the differences in insecure patterns, namely anxious and avoidant attachment to parents, have varying effects on LS during middle childhood in the collectivist context. It was also uninvestigated if friendship quality can predict LS above and beyond the effects of the attachment dimensions. Furthermore, the potential moderating and/or mediating roles of friendship quality between attachment dimensions and LS wait further examinations.

Overview

In line with the past research on attachment and friendship, and cultural arguments on attachment insecurity, the present study has specifically focused on the interplay between the attachment dimensions and friendship quality in predicting LS. Considering that mothers are the most significant attachment figure in predicting the quality of friendship and other child outcome variables in middle childhood and early adolescence (e.g., Kerns 2008; Schneider et al. 2001), anxious and avoidant attachment to mother were assessed representing the attachment dimensions. Considering that both attachment (in)security and friendship quality are the critical predictors of LS, this study aims to test the three alternative models to better understand both their unique and joined effects on LS. Specifically, first, after controlling for child age, it was tested if friendship quality and conflict predict unique variance on LS above and beyond the two attachment dimensions. Considering that attachment to mother has a developmental priority over friendship, they were entered to the equation in the second step followed by the friendship variables in the third step in the hierarchical regression analyses.

The second model aims to test the potential moderating effects of friendship quality. Using the same hierarchical regressions explained in the first model, the four interaction terms between the attachment dimensions, friendship quality, and conflict were entered in final step. Given that the interaction between attachment anxiety and avoidance reflects the four categories of attachment, namely, secure, preoccupied, dismissing, and fearful (Brennan et al. 1998), this interaction was also added to the equation in the final step to see if there exists a specific attachment style predicting LS above the effects of the two fundamental dimensions. The third models aims to test if friendship mediates the effects of attachment on LS. For this purpose, a model in which the two friendship variables mediate the effects of attachment dimensions on LS was tested.

Considering the cultural arguments summarized above, it was expected that the power of attachment avoidance would be stronger than attachment anxiety in all proposed models among Turkish children. Finally, considering potential gender differences on attachment and friendship, models were tested separately for girls and boys, expecting that the effects would be stronger among girls than boys.

Method

Following ethical approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited through three public middle schools in Ankara, Turkey. Recruitment letters explaining the aim of study and asking for parental approval for the student to participate in the study were sent to the parents of fifth to eight grade children. Children whose parental permission were received (consent rate = 80 %) were given the questionnaire battery during one of the class hours assigned by the classroom teacher. It took about 40 min for children to fill out the scales. The final sample consisted of 357 students (M age = 11.90, SD = 1.15; with a range of 10–14, 52 % males). Students completed the following measures together with the demographic questions.

Attachment Orientations

Anxious and avoidant attachment to mothers was measured using the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Revised (the ECR-RC) developed by Brenning et al. (2011) to measure attachment anxiety and avoidance for middle childhood. The ECR-RC was originally developed on the basis of Fraley et al. (2000) 36-item measure of Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (the ECR-R) developed for romantic relationships. Brenning and her colleagues modified the items of the ECR-R for middle childhood targeting attachment to parents. The ECR-RC contains two 18-item scales that measure attachment-related anxiety (e.g., “I’m worried that my mother doesn’t really love me”) and avoidance (e.g., “I prefer not to get too close to my mother” to mothers. Both the ECR-R and the ECR-RC were previously adopted into Turkish (Selçuk et al. 2005; Kırımer et al. 2013). Students rated items on a seven-point scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”. In the current study, the subscales of attachment anxiety and avoidance had satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas = 0.85 and 0.90, respectively).

Friendship Quality and Conflict

The quality and conflict in students’ friendship relations was measured via Bukowski et al. (1994) Friendship Qualities Scale (the FQS) consisting of 23 items. The FQS has five subscales (companionship, help, security, closeness, and conflict) and participants used 5-point scales ranging from “completely false” to “completely true” to rate the items. Participants were asked to respond to the items considering their best or close friends. The sex of the friends was not assessed.

The FQS was translated into Turkish and then back translated by three PhD students and faculty members who are fluent in both languages. Factor analyses on the items of the FQS yielded a clear two-factor structure representing friendship quality (18 items, e.g., “My friend would help me if I needed it”) and friendship conflict (5 items, e.g., “I can get into fights with my friend.”). Both friendship quality and conflict subscales had acceptable reliability coefficients (Alphas = 0.94 and 0.65).

Life Satisfaction

Huebner’s (1991) seven-item Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) was relied on using 6-point scales ranging from “completely disagree” to “completely agree.” The SLSS can be used for children of ages 8–18 (e.g., “My life is going well”). The SLSS was translated into Turkish, and then, back translated by three PhD students and faculty members who are fluent in both languages. The SLSS had satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha (0.82).

Results

Initial analyses yielded no significant sex differences on life satisfaction (LS) and attachment anxiety. However, there were significant differences on the remaining three major variables. As seen in Table 1, boys reported higher levels of attachment avoidance than girls (t (355) = 3.38, p < 0.001, d = 0.37). Girls reported higher level of friendship quality (t (355) = 4.50, p < 0.001; d = 0.48), but lower levels of conflict when compared to boys (t (355) = − 2.90, p < 0.01; d = − 0.32, respectively). Considering these significant differences, remaining analyses were run separately for girls and boys.

As seen in Table 1, age was significantly correlated with LS and attachment avoidance for girls (r = − 0.22, p < 0.01, r = 0.23, p < 0.01, respectively), but not for boys (r = − 0.04, r = 0.13, respectively). LS was significantly correlated with both attachment and friendship variables for both gender though the correlation between LS and attachment anxiety was stronger for girls (r = − 0.46, p < 0.001) than boys (r = − 0.25, p < 0.001). Attachment anxiety and avoidance were moderately strongly correlated for both boys and girls (r = 0.43, p < 0.001, r = 0.58, p < 0.001, respectively). Both attachment anxiety and avoidance were significantly correlated with friendship quality and conflict except that attachment anxiety was not significantly correlated with friendship quality for boys. As would be expected, friendship quality and conflict were negatively significantly correlated for both genders (see Table 1).

Hierarchical moderated regressions were run on LS to test the unique and moderated effects of attachment dimensions and friendship variables for girls and boys separately. In these analyses, age of children was entered in the first step to control for its effect. Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were entered in the second step followed by friendship quality and conflict in the third step to see their unique contribution to LS above and beyond the effects of attachment dimensions. Finally, all two-way interaction terms between attachment dimensions and friendship variables were entered in the fourth step to specifically test the moderating effects. All predictors were centered, and then, the interaction terms were produced before the analyses.

As seen in Table 2, age of girls, both not boys, significantly and negatively predicted their LS (β = − 0.22, p < 0.01). After controlling for the effect of age, supporting the expectations, attachment avoidance negatively predicted friendship quality for both girls (β = − 0.30, p < 0.001) and boys (β = − 0.41, p < 0.001). Whereas attachment anxiety did not predict boys’ LS (β = − 0.08, ns), it predicted girls’ LS (β = − 0.28, p < 0.01). The two attachment dimensions explained relatively larger unique variance on girls’ LS (26 %) than on boys’ LS (20 %). In the third step, friendship quality significantly predicted LS for both girls (β = 0.15, p < 0.05) and boys (β = 0.19, p < 0.01) above and beyond the effects of attachment dimensions with relatively weak beta weights, friendship conflict, however, did not have significant effect on LS. The friendship variables accounted for a significant additional unique variance on LS (4 % for girls and 6 % for boys). The total explained variances on LS by all predictors were relatively higher for girls (39 %) than boys (27 %).

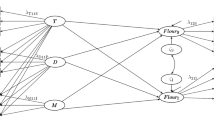

Out of five interaction terms, only the interaction between attachment avoidance and friendship quality among girls significantly predicted LS (β = − 0.21, p < 0.01). The significant interaction was plotted by following the procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991). As presented in Fig. 1, the pattern of the interaction showed that girls’ avoidant attachment to their mothers was affected differently depending on their level of friendship quality. Regardless of their attachment avoidance, girls with low levels of friendship quality had also low LS. However, LS of those with high friendship quality varied depending on their level of attachment avoidance. Those with high friendship quality had the highest LS if they had low attachment avoidance (i.e., secure attachment to mothers). However, if they had high level of attachment avoidance they still had relatively low LS even though they also had high friendship quality, suggesting that friendship quality enhances girls’ LS only if it accompanies low attachment avoidance.

Testing the third alternative, mediational model proposing that friendship quality and conflict mediate the link between the attachment dimensions and LS was run separately for girls and boys using the conventional approach with a series of multiple regressions. The bootstrap estimation was not used in testing the proposed model since two IVs (attachment anxiety and avoidance) should be entered into the equation simultaneously to control for their shared effects and only one IV can be used in the conventional bootstrap techniques. In these analyses, attachment anxiety and avoidance were used as the independent variables, friendship quality and conflict were used as the mediators, and the LS as the single dependent variable estimating all of direct and indirect paths. Since direct effects of both mediators (friendship quality and conflict) on LS were not significant in the analyses for girls, technically there was no significant mediating effect of friendship variables. However, as seen in Fig. 2, supporting the partial mediation effect, friendship quality partially mediated the relationship between attachment avoidance and LS among boys. Sobel test confirmed the significance of the indirect effect (t (170) = 1.99, p < 0.05). Significant indirect effect explained an additional 5 % of the variance on LS. Although both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance had direct effects on friendship conflict (β = 0.33, p < 0.001, β = 0.15, p < 0.05, respectively), friendship conflict, in turn, had only marginally significant effect on LS (β = − 0.13, p < 0.10) among boys. Hence, friendship conflict did not have a significant mediating effect.

Discussion

The main goal of the study was to identify independent and joined effects of the attachment dimensions (i.e., anxiety and avoidance), friendship quality, and conflict in predicting LS. Overall, results partially confirmed the expectation that attachment dimensions and friendship quality predict LS both uniquely (independently) and jointly both in interactive and mediating patterns in middle childhood. However, both magnitude and the pattern of association among the variables varied across gender, and friendship conflict did not predict LS above and beyond the effects of the attachment dimensions and friendship quality. Confirming the cultural expectation, avoidant attachment to mothers, rather than anxious attachment, predicted LS, especially for boys. Furthermore, attachment avoidance had additional effect on LS via the moderating effect of friendship quality for girls and mediating effect of friendship quality for boys.

Specifically, findings revealed that attachment avoidance among boys and both attachment avoidance and anxiety among girls predicted LS. Although friendship quality also independently predicted LS above the effects of attachment dimensions, the variance on LS explained by attachment dimensions, especially attachment avoidance was larger than friendship quality for both sexes, suggesting that attachment security is the critical source for sustained LS and friendship quality has an additional impact. The second and third models testing moderating and mediating associations, respectively, however, showed that, in addition to its weak effect on LS, friendship quality contributes to LS via moderating and mediating the effect of attachment avoidance. Similar to the findings of the current study, Rubin et al. (2004) found that perceived parental support and friendship quality independently predict higher global self-worth and better psychosocial function. Similar to the moderating effect found in this study, Rubin et al. found that high friendship quality moderates the effects of low maternal support corresponding insecure attachment on girls’ internalizing problems. Although they did not specifically measure avoidant and anxious attachment to mothers, these findings together suggest that friendship quality seems to play a moderating role between attachment security and child’s positive outcomes including LS for girls.

Although it was expected that attachment avoidance would be stronger than attachment anxiety in predicting LS, this was supported for boys only. Both attachment dimensions were similarly predictive of LS for girls. Similarly, in her study on Turkish university students, Kankotan (2008) found that both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance negatively predicted LS. Considering its strong role in anxiously attached women’s relationship conflict (e.g., Campbell et al. 2005), attachment anxiety seems be as critical as attachment avoidance for psychological adjustment of girls in middle childhood. Specifically, findings showed that anxious attachment to mothers is associated with friendship conflict. Overall, regardless of cultural differences, attachment-related anxiety seems to be systematically related with relationship conflict because of the working models of anxiously attached individuals that guide the perceptions of close relationships, including friendship, within the framework of threatening conflict and exaggerated need for support (Campbell et al. 2005). Therefore, although friendship quality and life satisfaction are mainly associated with lower level of attachment avoidance, conflict with peers is predominantly influenced by heightened attachment anxiety in Turkish culture.

Results also showed that attachment anxiety significantly predicted friendship conflict for both girls (β = 0.18, p < 0.05) and boys (β = 0.33, p < 0.05) in the mediational model though friendship conflict, in turn, did not predict LS once attachment dimensions and friendship quality were control for. In conclusion, these results suggest that both attachment avoidance and friendship quality predominantly predict LS and attachment anxiety predominantly predicts friendship conflict in middle childhood.

Regression results showed that age of children significantly predicted girls’ LS, but not boys’ LS, suggesting that probably because of their earlier pubertal stress, girls at the end of middle childhood and early adolescence may experience more stress that deteriorates their well-being relative to boys. After controlling for the effect of age, attachment and friendship variables together explained more variance in LS among girls’ (39 %) when compared to boys’ (27 %) implying that these close relationships play a more important role for girls than boys. These findings are in line with previous studies and arguments suggesting that the general link between close relationships and happiness are much stronger for women (Saphire-Bernstein and Taylor 2013). However, it is important to note that the idea that friendships might be more important for the well-being of girls than boys was not supported (Rose and Rudolph 2006). Specifically, friendship experiences accounted for more variance in boys (6 %) than girls (4 %). These findings are consistent with recent research among young adults (Demir and Davidson 2013). Thus, more research distinguishing different types of relationships are needed on the topic.

The moderating model indicated that friendship quality moderates the effect of attachment avoidance for girls only. The pattern of the moderating effect suggested that friendship quality strengthens the effect of low attachment avoidance or attachment security. In their moderated model in predicting child overall psychosocial adjustment, Booth et al. (2005) asserted that friendship quality plays a compensatory function when family relationships are inadequate. This assertion was not supported in this study considering the prediction of LS. However, consistent with some of the previous studies (e.g., Kerns et al. 1996), the pattern of interaction in this study implied that girls who are securely attached to their mothers can benefit more from friendship quality to enhance their LS than those who are insecurely attached. Therefore, it can be argued that friendship quality has an additive function rather than a compensatory function.

As shown in the mediated models, consistent with the previous findings on emerging adults in Turkey demonstrating that attachment avoidance had a dominant effect on the same-sex friendship quality (Özen et al. 2011), children’s avoidant attachment to their mothers, rather than attachment anxiety, had more adverse effects on friendship quality. Furthermore, extending the previous finding, the detrimental effects of attachment avoidance was not limited to friendship quality, but also extended to overall life satisfaction. It seems that attachment avoidance which is characterized by compulsive use of deactivating strategies and repression of attachment need and emotions from parents (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007) creates a serious risk factor for the optimal functioning in relationships with friends as well as life satisfaction in middle childhood in the Turkish cultural context.

Most research on the attachment and friendship predictors of happiness and LS has been conducted among adolescents or emerging adults (collage students) in the Western cultures. This study tested the effects of the two fundamental dimensions of attachment among secondary school children in Turkey. Although most of the findings are consistent with the findings of previous studies, some of the findings seem to be culture specific and still have critical implications for both schools and families. For instance, as outlined by Huebner and Diener (2008), life satisfaction and school satisfaction go hand in hand and enhancing LS does not only enhance one’s well-being and happiness but also helps her/him function better within the family and at school.

Comparison of sexes indicated that boys reported higher attachment avoidance to their mothers than girls. Meta-analytic studies have shown than men have higher attachment avoidance than women among adults (e.g., Del Giudice 2011). In a recent study, Del Giudice (2011) found marked sex differences in the distribution of insecure attachment patterns in middle childhood showing that boys were more avoidant than girls with a large effect size. Del Giudice argued that gender differences in attachment orientations begin about 6–7 years of age together with the other factors related with biased gender socialization roles and evolutionary demands. This is also consistent with the findings that boys’ attachment to mothers was weaker than girls in middle childhood and early adolescence (Kerns et al. 2006; Sümer and Anafarta-Şendağ 2009), probably because of their desire for more autonomy.

Girls reported higher friendship quality and lower conflict with friends than boys, which seem to be consistent with the previous findings (e.g., Kerns et al. 1996). Although Schneider et al. (2001) did not find a gender difference regarding the effect size for the association between child-parent attachment and peer relationship, gender socialization in friendship is expected to vary between girls’ and boys’ roles in Turkish cultural context. Girls’ friendships are usually characterized by harmony more communal sharing with less outdoor activities, whereas boys’ friendships are characterized by competition in outdoor activities, which may make them relatively prone to conflict with peers as compared to girls. Similar to the findings of this study, Israeli boys in middle childhood were found to have higher levels of conflict and use more hostile strategies and less compromising strategies in managing conflict than girls (Scharf 2013). Although the level of conflict was much lower than the friendship quality for both boys and girls, boys appear to be more conflict oriented than girls in both individualist and collectivist cultures in middle childhood (French et al. 2011).

Supporting the cultural expectation, attachment avoidance, but not attachment anxiety, predicted friendship quality, boys’ LS, and interacted with friendship quality in predicting girls’ LS, suggesting that attachment avoidance exacerbates the quality of peer relationships among Turkish children. Although a recent longitudinal study has indicated that best friendship quality is systematically associated with the development trajectory of low attachment avoidance (Fraley et al. 2013), cross-cultural generality of the predictive power of attachment dimensions should be examined further. However, recently Scharf (2013) found that anxious/ambivalent attachment which corresponds to attachment anxiety is also associated with low competence within close friendship. Although Scharf did not measure attachment avoidance, the predictive power of the two dimensions of attachment should be compared in further cross-cultural studies.

The findings of this study should be interpreted by considering several limitations. First, although this study has a culture-specific assumption regarding the effect of the fundamental attachment dimensions, validity of the findings should be confirmed using a comparison group from an individualistic culture. Although this study did not have a comparison group from the Western individualistic cultures, results, overall, support the idea that attachment insecurities may have varying dysfunctional and predictive values depending on the cultural context. However, potentially divergent functions of the fundamental attachment dimensions in explaining cultural differences in the dynamics of close relationships still await further research. Second, attachment to mothers and all outcome variables were measured in a cross-sectional design using only children’s self-reports which are open to response bias, common method variance, and inflated correlations. Third, only attachment to mothers was measured ignoring the role of father attachment. Considering that attachment security to father plays a critical role in social competence, especially in friendship conflict (Lieberman et al. 1999), future studies should also measure the role of anxious and avoidant attachment to fathers. Finally, given that mean level of life satisfaction is relatively high for all participants, the ceiling effect seemed to lower the variance in LS by limiting the magnitude of effect sizes.

Despite these limitations, the present study extends the previous work in this arena in three critical ways. First, the study examined the individual differences, not only on the basis of secure vs. insecure division, but also in the two fundamental dimensions of attachment anxiety and avoidance. Hence, the effects of multifaceted pattern of individual differences in attachment to mothers on child’s friendship quality and LS were depicted. Second, the interplay between attachment and friendship were examined considering the three main alternative explanations, namely, models of independent, moderated, and mediated effects. Third, the study was conducted in a non-Western culture in which the dynamics of both attachment and peer relationship has not been adequately explored.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Booth-LaForce, C., Rubin, K. H., Rose-Krasnor, L., & Burgess, K. B. (2005). Attachment and friendship predictors of psychosocial functioning in middle childhood and the mediating roles of social support and self-worth. In K. A. Kerns & R. A. Richardson (Eds.), Attachment in middle childhood. New York: The Guilford Press.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol. 1. attachment. London: Hogarth.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss. Vol. 2. separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York: Guilford Press.

Brenning, K., Soenens, B., Braet, C., & Bosmans, G. (2011). Attachment anxiety and avoidance in middle childhood and early adolescence: The development of a child version of the experiences in close relationships scale—revised. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28, 1048–1072. doi:1.1177/0265407511402418.

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 471–484. doi: 10.1177/0265407594113011.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J. G., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 88, 510–531. doi: 19391315. 20050301.

Cassidy, J. (2008). The nature of the child’s ties. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 3–22). New York: Guilford.

Del Giudice, M. (2011). Sex differences in romantic attachment: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 193–214. doi: 10.1177/0146167210392789.

Demir, M., & Davidson, I. (2013). Toward a better understanding of the relationship between friendship and happiness: Perceived responses to capitalization attempts, feelings of mattering, and satisfaction of basic psychological needs in same-sex best friendships as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 525–550. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9341-7.

Demir, M., Orthel, H., & Andelin, A. K. (2013). Friendship and happiness. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 860–870). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Demir, M., Özdemir, M., & Weitekamp, L. (2007). Looking to happy tomorrows with friends: Best and close friendships as they predict happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 243–271. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9025-2.

Demir, M., Özen, A., & Doğan, A. (2012). Friendship, perceived mattering and happiness: A study of American and Turkish college students. Journal of Social Psychology, 152, 659–664. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2011.650237.

Diener. E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 543–575.

Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7, 181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00354.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276.

Doumen, S., Smits, I., Luyckx, K., Duriez, B., Vanhalst, J., Verschueren, K., & Goossens, L. (2012). Identity and perceived peer relationship quality in emerging adulthood: The mediating role of attachment-related emotions. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1417–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.01.003.

Edwards, C. P., de Guzman, M. R., Brown, J., & Kumru, A. (2006). Children’s social behaviors and peer interactions in diverse cultures. In X. Chen, D. French, & B. Schneider (Eds.), Peer relations in cultural context. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350.

Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0031435. Advance online publication 104, 817–38.

French, D. C., Chen, X., Chung, J., Li, M., Shanghai, D. L., Chen, H., & Wang, L. (2011). Four children and one toy: Chinese and Canadian children faced with potential conflict over a limited resource. Child Development, 82, 830–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01581.

Friedman, M., Rholes, W. S., Simpson, J. A., Bond, M. H., Diaz-Loving, R., & Chan, C. (2010). Attachment avoidance and the cultural fit hypothesis: A cross-cultural investigation. Personal Relationships, 17, 107–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01256.x.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18, 192–205. doi:10.1521/scpq.18.2.192.21858.

Gorrese, A., & Ruggieri, R. (2012). Peer attachment: A meta-analytic review of gender and age differences and associations with parent attachment. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 41, 650–672. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9759-6.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the students’ life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–243. doi: 10.1177/0143034391123010.

Huebner, E. S., & Diener, C. (2008). Research on life satisfaction of children and youth: Implications for the delivery and school-related services. 376–392. Retrieved from: http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.okanagan.bc.ca/ehost/

Kağıtçıbaşı, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 403–422. doi: 10.1177/0022022105275959. 2005 36.

Kankotan, Z. Z. (2008). The role of attachment dimensions, relationship status, and gender in the components of subjective well-being. Unpublished master’s thesis. Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

Kerns, K. A. (2008). Attachment in middle childhood. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 366–382). New York: Guilford.

Kerns, K. A., Klepac, L., & Cole, A. (1996). Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the child-mother relationship. Developmental Psychology, 32, 457–466. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.32.3.457.

Kerns, K. A., Tomich, P. L., & Kim, P. (2006). Normative trends in children’s perceptions of availability and utilization of attachment figures in middle childhood. Social Development, 15, 1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006. 00327.x.

Kırımer, F., Sümer, N., & Akça, E. (2014). Orta çocuklukta anneye kaygılı ve kaçınan bağlanma: Yakın İlişkilerde Yaşantılar Envanteri-II – Orta Çocukluk Dönemi Ölçeğinin Türkçe’ye Uyarlanması [Anxious and avoidant attachment to mother in middle childhood: The psychometric evaluation of experiences in close relationships for children on a Turkish sample]. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları, 17, 45–57.

Ladd, G. W. (1999). Peer relationships and social competence during early and middle childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.333.

Lieberman, M., Doyle, A. B., ve Markiewicz, D. (1999). Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development, 70, 202–213. doi: 10.1080/0165025024400015.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L. A., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Mayseless, O. (2005). Ontogeny of attachment in middle childhood: Conceptualization of normative changes. In K. A. Kerns ve & R. A. Richardson, (Eds.), Attachment in middle childhood (pp. 1–23). New York: Guilford Press.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: The Guilford Press.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Adult attachment and happiness: Individual differences in the experience and consequences of positive emotions. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 834–846). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nangle, D. W., Erdley, C. A., Newman, J. E., Mason, C. A., & Carpenter, E. M. (2003). Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: Interactive influences on children’s loneliness, and depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 546–555. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7.

Oldenburg, C. M., & Kerns, K. A. (1997). Associations between peer relationships and depressive symptoms: Testing moderator effects of gender and age. Journal of Early Adolescence, 17, 319–337. doi: 10.1177/0272431697017003004.

Özen, A., Sümer, N., & Demir, M. (2011). Predicting friendship quality with rejection sensitivity and attachment security. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28, 163–181. doi: 10.1177/0265407510380607.

Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611–621. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. http://doi.org/cm3m3f

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55, 1093–1104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.10.1093.

Rothbaum, F., Rosen, K., Ujiie, T., & Uchida, N. (2002). Family systems theory, attachment theory, and culture. Family Process, 41, 328–350.

Rubin, K. H., Dwyer, K. M., Booth, L, C., Kim, A. H., Burgess, K. B., & Rose-Krasnor, L. (2004). Attachment, friendship, and psychosocial functioning in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 24, 326–356. doi:10.1177/0272431604268530.

Saphire-Bernstein, S., & Taylor, S. E. (2013). Close relationships and happiness. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 821–833). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scharf, M. (2013). Children’s social competence within close friendship: The role of self-perception and attachment orientations. School Psychology International 34,1–15. doi: 10.1177/0143034312474377

Schmitt, D. P., Alcalay, L., Allensworth, M., Allik, J., Ault, L., & Austers, I., (2004). Patterns and universals of adult romantic attachment across 62 cultural regions: Are models of self and other pancultural constructs? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 367–402.

Schneider, B. H., Atkinson, L., & Tardif, C. (2001). Child–parent attachment and children’s peer relations: A quantitative review. Developmental Psychology, 37, 86–100.

Selçuk, E., Günaydin, G., Sümer, N., & Uysal, A. (2005). A new measure for adult attachment styles: The psychometric evaluation of experiences in close relationships—revised (ECR-R) on a Turkish. Turkish Psychological Articles, 8, 1–11.

Selçuk, E., Günaydin, G., Sümer, N., Harma, M., Salman, S., Hazan, C., Dogruyol, B., & Ozturk, A. (2010). Self-reported romantic attachment style predicts everyday maternal caregiving behavior at home. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 544–549. doi 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.05.007

Sümer, N., & Anafarta-Şendağ, M. (2009). Orta Çocukluk Döneminde Ebeveynlere Bağlanma, Benlik Algısı ve Kaygı. [attachment to parents during middle childhood, self-perceptions, and anxiety]. Turkish Journal of Psychology, 24, 86–101.

Sümer, N., & Kağıtçıbaşı, Ç. (2010). Culturally relevant parenting predictors of attachment security: Perspectives from Turkey. In P. Erdman & K-M. Ng. (Eds.), Attachment: Expanding the cultural connections (pp. 157–180). New York: Routledge Press.

Triandis, H. C., Bontempo, R., Villareal, M. J., Asai, M., & Lucca, N. (1988). Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 323–338. doi: 10.1177/106939719502900302.

UNICEF Office of Research (2013). ‘Child well-being in rich countries: A comparative overview’, Innocenti Report Card 11, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence. http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc11_eng.pdf

van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Kroonenberg, P. (1988). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: A meta-analysis of the strange situation. Child Development, 59, 147–156. doi:1887/11634.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2008). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: Universal and contextual dimensions. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 880–905). New York: Guilford Press.

Zayas, V., Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Aber, J. L. (2011). Roots of adult attachment: Maternal caregiving at 18 months predicts adult attachment to peers and partners. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2, 289–297. doi: 10.1177/1948550610389822.

Acknowledgement

I’d like to thank Ece Akca, Fulya Krimer, Burak Doğruyol, and Ezgi Sakman for their help in collecting data, and translation, and back translation of the scales, and Melikşah Demir for his valuable comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sümer, N. (2015). The Interplay Between Attachment to Mother and Friendship Quality in Predicting Life Satisfaction Among Turkish Children. In: Demir, M. (eds) Friendship and Happiness. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9603-3_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9603-3_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9602-6

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9603-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)