Abstract

International educational surveys have repeatedly shown that the degree of ethnic educational inequality varies across countries. Previous studies that examined the causes for ethnic educational inequality in a comparative perspective further suggest that institutional and societal characteristics of destination countries partly account for country differences. The article builds upon these recent findings and upon hypotheses about the relationship between welfare states and immigration and integration processes. We assume that two different dimensions, namely egality and diversity of the destination countries structure educational decisions of immigrants. Thus, educational success is partly out of individual control which is why we speak of a process of cognitive exclusion. With data from PISA 2003 and 2006 we examine the effects of welfare state institutions and diversity of host countries on individual educational success by applying multilevel regressions. It shows that strong welfare states also feature educational systems that lead to high performance in general and reduce the individual risk of cognitive exclusion for immigrants, contradicting common “moral hazard” assumptions. The diversity in terms of size and heterogeneity of the immigrant community further seems to provide incentives for assimilative educational behaviour of immigrants.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

International migration movements are a constituent part of human history. However, since the end of the twentieth century, border-crossing migration reached a new dimension. This is not only a consequence of a new political world order but also a side effect of ongoing internationalisation processes. At the same time, many industrialised countries face the growing challenges of demographic changes. In order to maintain sustainable social security systems and economic prosperity, these countries will have to rely on immigration—and the successful social integration of immigrants. As an unintended consequence of policies that permit or even increase immigration, the social and ethnic composition of schools has changed fundamentally in most receiving countries, and thereby, ethnic inequalities became a new challenge for educational institutions. Social integration can be conceived of as a process of inclusion into the functional systems of the host society, most importantly the labour market. A precondition of economic integration is the availability or acquisition of educational credentials. Hence the successful educational attainment of immigrants and their offspring in the educational systems of their host countries serves as a long-term indicator of integration. However, research on ethnic educational inequality has repeatedly shown that immigrants in most countries lag behind their native peers. The degree of inequality is quite pronounced in a number of countries: for example, the OECD PISA study 2009 has shown that one third of young immigrants in Germany do not score higher than the first proficiency level in reading, which is defined as educational poverty (Solga 2009).Footnote 1 By comparison, only 12 % of native Germans fall into this category. Being educationally poor at age 15 decreases the odds of following a higher education track and increases the risk of being unemployed in the future. From a societal point of view, educational poverty entails substantial follow-up costs.

International comparative studies have shown that learning gaps between natives and immigrants vary across countries—even if relevant factors such as social status and language use are controlled for. Immigrants in Germany whose parents had completed lower secondary education reached 411 points on the reading scale in PISA 2009, whereas immigrants in Canada with the same level of parental education scored more than 70 points higher. Hence it is assumed that institutional factors at the country level shape learning and integration processes. Due to substantial differences regarding the educational integration of young immigrants across countries, we assume that individual educational poverty corresponds with specific features of national institutions and social structures. If we find institutional effects despite controlling for parental socio-economic status and immigrants’ origin-contexts, we believe that educational poverty is an individual but institutionally shaped, feature (Hinz et al. 2004). In our chapter we aim at answering the question which institutions and structural features of host countries influence the educational success or failure of young immigrants.

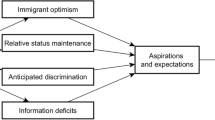

Our analysis links to sociological research devoted to the causes of internationally varying integration outcomes and to hypotheses and findings of comparative welfare state research. We analyse the contextual factors at the country level in two different dimensions: egality and diversity. Egality refers to the degree of redistribution and income equality in a country, diversity comprises heterogeneity and size of the immigrant population. We argue that these societal dimensions influence the educational investment decisions of immigrant families. In the following section we summarise previous research of institutional effects on education. Subsequently, we describe our theoretical model based on the subjective expected utility theory. In a next step we describe our database and methods and present some descriptive results. We apply multilevel regressions in order to estimate the influence of egality and diversity in the host countries on the risk of being educationally poor, controlling for relevant factors at the household and school level.

2 Why do Integration Outcomes Vary Cross-Nationally? Theory and Research

Our analysis builds on two interdisciplinary fields of research. First, we draw on research approaches and findings from the field of rather micro-oriented sociological research on the educational attainment of immigrants. Second, we refer to comparative political economy approaches that examine the interaction between immigration and welfare state institutions. Research in the first field has become more elaborate with the availability of large-scale educational assessments such as TIMSS/PIRLS and PISA. The results of these studies as well as further scientific research have shown that there are significant differences between countries with regard to the educational achievement of immigrants (Buchmann and Parrado 2006; Stanat and Christensen 2006). Empirical findings suggest that these differences are not only due to a more favourable composition of immigrant populations (Marks 2005; Schnepf 2007). In many countries, for example France, the Netherlands and Switzerland, immigrants perform significantly worse than natives, even when language use and socioeconomic status are controlled for (Schnepf 2007, p. 544). Furthermore, different studies suggest the existence of distinct patterns: immigrants in English-speaking countries perform better in relation to their native peers than in most continental European countries (Entorf and Minoiu 2004). A first approach to explaining the residual effects of immigrant status on educational achievement has linked patterns of ethnic educational inequality with existing typologies of immigration or integration regimes. It has been assumed that traditions of immigration and incorporation are likely to shape ethnic inequality. Some studies were able to show that “exclusionary regimes” produce the most pronounced learning gaps between immigrants and natives, whereas “inclusionary regimes” seem to be most successful in integrating immigrants at school (Buchmann and Parrado 2006, p. 347). Although these findings contribute to our understanding of interactions between institutions and integration processes, they could not clarify which institutions actually play what kind of role in immigrant integration. Since most of the former empirical models measured institutional structures by including dummy variables that indicated specific countries or groups of countries, these studies did not explain the mechanisms that create the differences observed between countries. A solution for this shortcoming are multilevel models that include measured characteristics of countries as independent variables. Levels et al. (2008) applied such a multilevel regression design and were able to show that traditional immigration countries do not have a significant effect on the mathematical achievement of immigrants if individual characteristics and features of the immigrant community and their countries of origin were controlled for—thereby contradicting findings of previous studies. They revealed that the average socioeconomic capital and the size of the ethnic community have positive effects on the educational achievement of immigrants. However, the independent variable “traditional immigration country” still remains a proxy variable that does not capture the relevant institutional characteristics of the respective country.

We build upon these findings, but enhance our perspective by referring to existing research on the complex interplay between processes of immigration, integration and welfare state institutions. The repercussions of ongoing immigration for the sustainability of social security systems have been intensively discussed since the 1990s (Bommes and Geddes 2000; Boeri et al. 2002; Banting and Kymlicka 2006). This field of research can be broadly divided into two positions: one that treats the welfare states as an independent variable shaping immigration and integration processes, and another one that sees the welfare state and its sustainability as dependent on immigration and integration. The first perspective is focused on the influence of welfare states on immigration processes and became prominent with the “welfare magnets” hypothesis (Borjas 1990). Based on human capital theory, this approach states that strong welfare states tend to attract less qualified immigrants who are more likely to depend on welfare. This model thus assumes that migration decisions are mainly determined by expectations of the potential income in the destination country. Immigrants are positively selected if the degree of income inequality in the destination country is higher than in the country of origin (Borjas 1994, p. 1689). This assumption neglects the impact of institutional constraints such as immigration regulations as well as considerations about the meaning of networks for migration decisions (Nannestad 2007, p. 516). Empirical evidence regarding the welfare magnets hypothesis is mixed so far (ibid. 519).

Building upon the welfare magnets hypothesis, the relation between welfare state institutions and integration processes has mainly been discussed from a moral hazard perspective. Welfare states with a high degree of redistribution always encourage free riders, among immigrants as well as among natives. However, the prospects of generous social security might reduce incentives for immigrants to invest into their integration. Koopmans (2010) points out that immigrants in welfare states with strong de-commodification have lower incentives to invest in their human capital (e.g. through language learning) as the coercion to participate in the labour market is lower. Furthermore, the relative deprivation that results from being on welfare might be lesser for immigrants than for natives since immigrants refer to the situation in their countries of origin whereas natives compare themselves with other natives. According to this assumption one would expect bigger problems of structural integration in strong welfare states. Indeed, empirical research has shown that the labour market participation of immigrants is higher in liberal welfare regimes with flexible labour market regulation (Kogan 2006). On the other hand there is evidence that labour market integration does not protect immigrants from poverty and deprivation. According to the above-mentioned evidence, immigrants are better-off in strong welfare states if one considers poverty rates and (the availability of) social rights (Morissens and Sainsbury 2005).

Most liberal welfare regimes have a long tradition of immigration, and as such they have efficient institutions that regulate immigration at their disposal, but they also often pursue a policy of laissez-faire when it comes to integration. As a consequence, they encourage segregation and compel immigrants to rely on family structures, thereby increasing the risk of segmented assimilation outcomes.

It thus remains an unanswered question which form of welfare state fosters the structural assimilation of immigrants and maintains societal integration in the long run. In addition, there is not yet enough empirical evidence regarding the effect of institutions on different dimensions of individual integration. Previous empirical research focusing on the relation between welfare states and immigration and integration mainly relied on aggregated data (Morissens and Sainsbury 2005). With this kind of research design it is not possible to distinguish the effects of single institutions. It is thus impossible to tell whether high unemployment rates in strong de-commodifying welfare states were a result of negative selection at immigration (welfare magnets) or of unfavourable incentives for assimilation (moral hazard).

In addition, previous research neglected the experiences of the second generation, which would allow for a long-term perspective on integration. Lastly, most of the studies that have been conducted so far did not explicate the individual mechanisms that lead to measured integration outcomes at the macro level. Therefore, we aim to develop a macro–micro model by arguing that egalitarian welfare regimes provide better opportunities for immigrant families to invest in their children’s education, as the prospects of intergenerational social mobility are perceived as relatively high. We will elaborate on this argument in the next section as it serves as the basis for our empirical analyses.

3 An Explanation of Integration Processes and Educational Decisions

Educational poverty of immigrants can be conceived of as a special case of individual social integration. In order to explain immigrant integration we draw on the model of intergenerational integration as developed by Hartmut Esser (2006, 2008). This approach provides a synthesis of the most important theoretical accounts of immigrant integration, namely classical assimilation (Park 1950), segmented assimilation (Portes and Zhou 1993; Portes and Rumbaut 2001) and new assimilation (Alba and Nee 1997, 2003).

The model takes a subjective expected utility (SEU) perspective and assumes that immigrants decide whether to orient their action towards the receiving context (rc-option) or towards the ethnic community (ec-option). These (rc- or ec-oriented) actions can be conceived of as investments in the production of desirable goals and goods (Esser 2008, p. 88). As opposed to natives, first- and second-generation immigrants often face the situation that relevant strategic resources for the production of their goals are devaluated as a result of the migration process. As a consequence, these resources (e.g. host country language ability or educational credentials) have to be reconstituted (e.g. through language learning) before they can be used in the investment process. As empirical analyses show (Esser 2006), these re-investments in host country specific resources do not occur necessarily, i.e. under certain (contextual) circumstances immigrants remain oriented towards their ethnic community. The retention of the ec-option is especially likely in countries that exhibit pronounced ethnic seclusion. Ethnic seclusions can be conceived of as limited opportunities such as restricted access to housing or the labour market for immigrants.

Theories on assimilation and ethnic stratification thus have to explain why immigrants chose either the rc- or the ec-option, thereby creating different structural integration outcomes at the macro level. The model of intergenerational integration assumes that immigrants will tend towards the receiving context (e.g. invest in language learning) if the subjective evaluation of the utility that arises from the benefit of the investment (e.g. income) weighted with the probability of success, outweighs the costs and the utility of the status quo (ethnic retention). The focus on investment decisions at the micro-level has the advantage that it is very comprehensive. For instance, also the investment in gathering information on the host-countries’ educational system can be regarded as a matter of investigation.

The benefits of both alternatives (ec- and rc-option), the probabilities of their success and the costs depend on the respective empirical conditions in the receiving country, the ethnic community and on the available individual resources (Esser 2008, p. 89). These marginal conditions that structure individual expectations and evaluations have been neglected in many empirical accounts as the main focus was directed towards individual resources and ambitions. The segmented assimilation theory was among the first to recognise the importance of the receiving context for the production of different integration outcomes.Footnote 2 Esser’s model of intergenerational integration builds upon this approach. In particular, ethnic diversity in the host county and the size of the immigrant population are considered to serve as crucial marginal conditions for integration. Countries with a traditionally low ethnic diversity, which means that ethnic minorities are rather homogeneous, are expected to produce ethnic seclusion, since homogeneous immigrant groups enable political mobilisation and institutional completeness (Breton 1964). Additionally, bigger ethnic groups make contact with natives less likely and might be an impediment to language learning or labour market access (Esser 2008, p. 89).

The educational success—or in the case of educational poverty—the educational failure of immigrants can now be considered as a result of individual assimilative decisions. For this reason, we have to explain the individual investment decisions in education. The sociology of education developed formal models that allow an analytic reconstruction of these investment decisions (Boudon 1974, p. 29f; Becker 1993; Breen and Goldthorpe 1997; Esser 1999, pp. 266–275; Becker 2000; Esser 2008). These models take into account the expected probability of an amortisation of the costs and the expected benefit of education. Recently, institutional and socio-structural characteristics of the destination countries were also integrated into the analyses of immigrants’ educational attainment (Levels et al. 2008, p. 883). It is assumed that the expected benefits and probabilities of amortisation for immigrants and their offspring depend on the institutions and social structures of the host countries. The social security system is one part of this relevant host country structure. It is not yet clear how welfare state institutions influence educational investment decisions. The chance of getting welfare benefits without labour market participation may influence the immigrants’ evaluation of the free and secure status quo (ethnic retention). Strong welfare states are likely to foster external social closure if labour market regulation (e.g. protection from dismissal) or high non-wage labour costs decrease incentives for employers to hire “risky” employees such as immigrants.

But what is the situation for first-generation immigrants facing decisions about investing into their children’s education? Building upon the model of intergenerational integration, we look at two alternatives: “sq” represents the decision of non-investment into receiving-context resources, e.g. a retention of the status quo. “In” stands for the decision for educational investments, for example the aim to obtain a certain degree (Esser 2006, p. 40). The selection of one of these alternatives can be formally expressed in the logic of the subjective expected utility theory. We divide the expected probability of success (e.g. the amortisation of the investment decision) into two parts: on the one hand there is a subjective probability of acquiring the desired degree [p(degree)], on the other hand there is a subjective probability to employ this degree in order to reach a certain status (e.g. upward social mobility [p(mobility)]). This differentiation has not been considered so far.

whereby:

From an immigrant’s perspective, the expected utility of the status quo in Eq. (5.1) is known and secure.Footnote 3 The expected utility of the investment decision in Eq. (5.2) is insecure, since the individual does not know with certainty if the educational investment will be amortised through the acquisition of the desired degree [p(degree)] and through the achievement of an adequate social position [p(mobility)]. Thus, we assume that the probability weight of the benefit in Eq. (5.2) consists of two components that are multiplicatively combined. According to this, p(in) = 0 if either p(degree) or p(mobility) equals zero. Thus, the subjective expected probability of the investment’s amortisation is low if either the chances for the acquisition of the desired degree [p(degree)] are low or if the likelihood of upward mobility through educational credentials [p(mobility)] is low.

Drawing on this assumption we can derive hypotheses about the impact of welfare state institutions on the production of educational poverty. These hypotheses are mainly directed towards the parameter p(in): liberal welfare states with an unequal social structure provide attractive positions at the upper end of the income distribution scale. However, the likelihood of acquiring these positions is relatively low, especially if they are occupied by natives. By contrast, the probability of being upwardly mobile is higher in welfare regimes with a more equal social structure and a high degree of redistribution where insecurity regarding the amortisation of educational investment is lower. In other words: the likelihood of a maximised benefit by reaching a top-position may be reduced in egalitarian regimes, but the chances of upward mobility for the second generation are expected to be markedly higher. If the investment fails, immigrants in strong welfare states are less dependent on the solidarity of the ethnic community; thus the likelihood of ethnic closure and self-segregation is lower. If immigrants in liberal welfare states neglect their ethnic ties by focusing on the acquisition of receiving-context capital they are threatened by marginalisation if the investment carries a high risk of failure. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the comprehensive public education systems in strong welfare states along with the prospects of being secured by welfare institutions will increase the likelihood that immigrants choose the educational investment, especially for lower-status groups. This assumption goes back to findings of educational research that have shown that families with lower social status overestimate the cost parameter while underestimating the possible benefits of education (Boudon 1974; Erikson and Jonsson 1996; Becker 2000). By contrast, the chances of the amortisation of the receiving context investment is lower in weak welfare states with strong inequality since p(degree) as well as p(mobility) are lower under these conditions. Why should a costly investment be undertaken if the chances of educational success and the likelihood of reaching a higher-status position are low? Under these circumstances, immigrants are likely to prefer the alternative that has a lesser benefit but is secure and inexpensive—which is the retention of the ethnic option (sq). Since this orientation towards the ethnic community inhibits cultural assimilation, the risk of educational poverty is higher. In contrast to moral hazard assumptions we thus assume a lower risk of educational poverty for second-generation immigrants in countries with high redistribution (egality) and diversified ethnic communities (diversity).

4 Data and Methods

In order to test our hypotheses empirically we draw on data from the OECD PISA 2009Footnote 4 study. This survey is especially suitable for our research question since it comprises about 47,000 immigrants in more than 60 countries. PISA seeks to measure the competencies of 15-year-old pupils in order to assess their abilities to face the challenges of contemporary knowledge-based economies. The assessment focuses on three dimensions: reading, mathematics and science. Competence is measured using continuous scalesFootnote 5 and so-called “proficiency levels”. Even though these levels have been computed from the continuous distribution of the test scores, they are not completely arbitrary: Performing at a given proficiency level corresponds to the ability of solving tasks of a certain difficulty level. If a pupil reaches a certain level, s/he is able to solve more than 50 % of the tasks at this level as well as tasks of lower levels. Reading competence is divided into five proficiency levels in PISA. Pupils who do not reach the first proficiency level in reading are not able to develop the most basic reading competencies—they are “functionally illiterate”. Students who reach the first proficiency level are capable of completing only the least complex reading tasks in PISA, such as locating a single piece of information, identifying the main theme of a text or making a simple connection with everyday knowledge. They only acquired the most basic reading competencies and thus have to be considered as “educationally poor” if one considers the requirements for successful labour market participation in modern societies (Solga 2009, p. 400). Thus, our dependent variable “educational poverty” is a dummy variable for pupils who do not reach the second proficiency level (1 = educational poor).

We measure the diversity of host countries with two variables: the share of immigrantsFootnote 6 as well as the degree of homogeneity within the immigrant population regarding size and quantity of different ethnic communities.Footnote 7 We calculated the Herfindahl-Index of concentration which measures the sum of the squared proportions of immigrant groups. In order to capture the impact of welfare state institutions and social structure (egality) we draw on the Gini-Index of income inequality and on the amount of social contributions as a measure of redistribution.Footnote 8 We further include a dummy variable that indicates whether a country pursues a policy that promotes immigration since we expect that these countries provide advantageous integration conditions (UN World Population Policies 2010). As a means to control for general “level effects” of an education system we ran further models that included the share of educationally poor natives, the mean reading score of natives as well as the range of reading achievementFootnote 9 and the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country.

In order to isolate the context effects at the country level we control for a number of relevant characteristics of the household and school level. These are: a dummy variable to distinguish second-generation from first-generation immigrants (1 = second), a dummy variable for gender (1 = girl), the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS)Footnote 10 and a dummy variable indicating foreign language use at home. We expect better outcomes (e.g. lower odds of being educationally poor) for the second generation, lower risks of educational poverty for higher-status pupils and a higher risk of being educationally poor for those who mainly speak a foreign language at home.

At the school level we control for private schools (1 = private), the autonomy of the schools regarding the recruitment of teaching staff (1 = autonomous), the location of the school (1 = large city), the share of immigrants at school, the average socioeconomic status of the school and the range of reading scores at the school, measured as the difference between the fifth and ninety-fifth percentile (the latter three were gathered from pupil data). We expect better outcomes for private and autonomous schools since these features are supposed to lead to better teaching conditions due to more competition and higher flexibility and more funding. The share of immigrants at school should not have a significant effect as long as the average socioeconomic status and the average achievement level are controlled for—otherwise this would indicate discrimination or other impeding factors.

Our research question is directed towards the effect of country characteristics on pupil performance, controlling for characteristics of the pupils’ families and schools. This entails examining nested data: pupils are nested in schools that are nested in countries. This data structure requires techniques that account for the fact that pupils in schools and schools in countries may resemble each other, meaning that the individual or school-related error terms of a regression model may be correlated. Multilevel regression techniques are able to rule out this circumstance, thereby allowing for an account of contextual effects (Snijders and Bosker 1999; Luke 2004; Goldstein 2003). Since our dependent variable is dichotomous, we apply logistic multilevel regressions using the software package MLwiN.

All variables are grand mean-centred and cases with missing values on any of our variables were excluded from the analyses. The PISA design entails varying case numbers at the country level, which involves a standardisation of the final pupil weight.Footnote 11 The models were set up for all five plausible values.Footnote 12 The model can be depicted as follows:

X represents the independent variables at the pupil level, W the independent variables at the school level and Z the independent variables at the country level. The subscript i denotes pupils, j schools and k countries.

In logistic models, the residual variance at the lowest level is fixed to π2/3. Including a further covariate xk will influence the vector of coefficients x, even if xk and x are uncorrelated (Mood 2010). This impedes the comparability of effects between nested models. Therefore, we will restrict the interpretation of the effects to their significance instead of explicitly comparing their change across different models. Table 5.1 gives an overview of the variables and their distributions. We restrict our analyses to first and second generation immigrants.

It is striking that almost one third of all immigrants have to be considered educationally poor. It is only in one quarter of all countries that less than 20 % of immigrants fall into this category (see Fig. 5.1). The share of educationally poor immigrants varies between 11 % in Canada and 90 % in Colombia. About one half of our sample belongs to the second immigrant generation (born in the test country to foreign-born parents). Almost 50 % of all immigrants in our sample mainly speak a foreign language and 50 % are girls. 14 % of all respondents in our sample attend private schools and 73 % are enrolled in a school with autonomy in staffing. The average share of immigrants at schools is 32 %.

At the country level, the Gini-Index varies from 25 in Sweden to 58 in Colombia. Social contributions vary from 0.3 % to 57 % in Germany. The share of immigrants is smallest in Colombia (0.2 %) and largest in Jordan with almost 50 %. Norway has the immigrant population that is the most diverse whereas Bulgaria has an almost homogeneous immigrant community. Argentina, Canada, Finland, Israel and Sweden seek to increase immigration. Argentina is the country where natives perform worst, whereas Finland is the highest-performing country in our sample. Jordan is the country with the smallest GDP; by contrast Luxembourg has the highest productivity per head.

5 Results

As a descriptive approach we plotted the relationship between the dependent variable “educational poverty” (aggregated at the country level) and the macro indicators of egality and diversity. We see that our hypotheses on egality can be confirmed in this bivariate approach. The higher the income inequality in a country, the higher the degree of educational inequality seems to be (measured as the share of educationally poor immigrants, Pearsons r = 0.65). By contrast, the higher the social contributions, the lower is the degree of educational poverty among immigrants (r = −0.36). If we look at the diversity dimension we see that a bigger immigrant community seems to correspond with lower educational poverty among immigrants (r = −0.34). However, the relationship between homogeneity in the immigrant population and immigrant’s educational poverty is not so clear.

How does this picture change if we analyse educational poverty at the individual level, thereby controlling for composition effects? By estimating the hierarchical logistic model we test whether our hypotheses hold in a multivariate approach.

According to the empty model (not shown here), we see that a multilevel model is appropriate since 20 % of the overall variance can be explained by characteristics of the respective higher levels (country and school) (Figs. 5.2, 5.3, and Table 5.2).

The first five models M 1–5 depicted in the first column include one predictor of the country level at a time. If the Gini-Index is the only independent variable, the model estimates a highly significant positive effect, i.e. the higher a country’s Gini-Index, the higher is the individual risk of educational poverty. Among the other factors at the country level, only the social contributions have a significant impact on the risk of educational poverty; both of these indicators of egality show effects that confirm our hypothesis, i.e. more income equality and more redistribution are associated with less income inequality.

The next model (6) now includes all country-level predictors that depict aggregated “gross” effects; this means that possible composition or selection effects are not ruled out in this model. There are only two significant effects: the higher the Gini-Index, the higher is the risk of educational poverty. If the Gini-Index is controlled for, the effect of redistribution is no longer significant. By contrast, the size of the immigrant population in a country now becomes significant: the larger a country’s immigrant population, the lower is the individual risk of poor education. The variance partition coefficient shows that the variance at the country level is reduced by one half after the independent variables at the country level are controlled for. Model 7 additionally includes school level predictors. Strikingly, the effect of income inequality is no longer significant if the average socioeconomic status of schools and the range of achievement at schools are controlled for. This suggests that countries with a higher average SES of schools are countries with lower income inequality. On the other hand, the risk-reducing effect of redistributions gains significance.

Model 8 now controls for composition effects by accounting for relevant factors at the pupil and household level. Second-generation pupils as well as pupils of a higher socioeconomic status and girls have a lower risk of being educationally poor, whereas students who mainly speak a foreign language at school have an almost 50 % higher risk of being educationally poor. At the country level, the effect of redistribution has become significant now. Once composition is controlled for, immigrants in a country with higher social contributions face a lower risk of failing at school. The same still holds for countries with bigger immigrant populations. In this model, the variance at the country level is reduced to about 7 %.

The next four models control for “level effects” by including indicators of overall educational performance and economic productivity. The higher the average achievement of natives, the lower is the risk for immigrants to fail at school. It seems that the overall performance of the educational system is confounded with egality. The effect of redistribution is no longer significant, indicating that countries with a high performance are countries with strong redistribution. The same holds if one controls for the share of educationally poor natives, while the range of achievement as well as GDP do not have significant effects; however, the egality dimensions again gains significance in the last two models (Gini, sig. at 10 %-level in Model 12). The pseudo-r² shows that model 9 and 10, e.g. the “full” models controlling for system performance, are the best-fitted models.

Up until now, we have treated immigrants as one rather homogeneous group, controlling only for generation status, socioeconomic and cultural background and language use. However, theory and research on immigrant integration have repeatedly shown that “immigrants are not like immigrants”, meaning that there are significant differences between immigrants of different origin. In our first model we controlled for destination and community effects, but not yet for origin effects. Table 5.3 gives the result of another multilevel model which controls for origin of immigrants by including dummy variables for the respective origin regions at the pupil level. The sample is smaller since the information on origin is not available for all pupils. This means that the number of destination countries is reduced to 22. The empty model (0) gives information about the distribution of the overall variance across the different levels. Compared to the bigger sample of 38 countries, only about 10 % of the overall variance in educational poverty can be explained by differences between destination countries. The first model controls for differences due to origin, which reduces the country-level variance by about one third. We see that immigrants from the Caribbean have the highest risk of being educationally poor (when compared with immigrants from Western Europe). Immigrants from the Middle East, Maghreb and South America have a four times higher risk of being educationally poor than immigrants from Western Europe. There is no significant difference between immigrants from Eastern Europe, the USA, the former Soviet Union, and South–East Asia and China and those from Western Europe. Adding the destination country variables of egality and diversity (model 2) reveals no significant effect and only little more explained variance. At the school level (model 3), the average socioeconomic status and the achievement dispersion as well as the autonomy in staffing show significant effects. These factors explain much more variance than origin and destination countries alone do (McKelvey and Zavoina R² = 0.24). The last model finally controls for composition effects due to pupil level characteristics. Compared to the first model, some of the origin effects lost significance and strength. Overall, there are still significant differences between groups of different origin. These differences strongly suggest that immigrants should not be treated as a homogenous category. The destination effects of egality and diversity do not contribute to the explained variance, which is probably due to the substantially smaller sample used for this model.

6 Conclusion

Our chapter aimed to assess the causes of immigrants’ educational poverty. Previous research has shown that some countries exhibit better structural integration outcomes than others. However, in many countries a significant part of young immigrants is threatened by an exclusion from societal integration mechanisms as a consequence of poor education. Educational poverty is not only the result of individual capabilities and opportunities but it is shaped by institutions. To this day, research lacks a systematic assessment of the relationship between host country institutions and immigrants’ educational decisions. This does not only apply to scarce empirical evidence but also to the theoretical linkage between specific macro structures and individual behaviour. We tried to make a first attempt to overcome these research gaps. Our main focus is on the impact of the socio-cultural and institutional effects of destination countries if the compositional effects at the pupil and school level were controlled for. We referred to hypotheses and findings from comparative educational and political economy research. By building on Esser’s SEU-model of immigrants’ investment decisions, we assumed that the egality and diversity in host countries influence the educational decisions of immigrants. We hypothesised that states with low income inequality and pronounced redistribution provide advantageous opportunities for immigrants to take the risk of insecure investments in education. We further supposed that the degree of diversity in a country prevents the formation of ethnic boundaries, thereby fostering integration.

Our results suggest that national institutions may indeed trigger these expected effects. Income inequality seems to increase the risk of educational poverty, whereas experience with immigration—measured as the size of the immigrant population—reduces the individual risk of educational poverty. If individual and school characteristics are controlled for, the effect of income inequality loses significance, but social contributions as an indicator for redistribution gain significance (e.g. more redistribution leads to less educational poverty). If the average achievement of natives as an indicator of the general performance of the educational system is controlled for, the effect of redistribution is no longer significant. This suggests that high-performing countries are also countries with more redistribution.

Thus our hypotheses are partly corroborated, though the significance of the macro effects is low. This means that our approach and our results are not yet conclusive. International comparative multilevel designs often face the problem of low case numbers at the highest level or of insufficient control of relevant factors due to missing data at the country level. A further shortcoming is our data base; the PISA survey provides valuable information that allows an international comparison of educational processes. However, since the data is cross-sectional, it does not permit the assessment of actual causal effects on educational behaviour. For instance, a high value of the Gini-Index can also be an outcome of the education system’s bad performance in the past. But a current situation which has evolved in the past is nevertheless the context which drives actors’ decisions at the micro-level. Moreover, analysing immigrants’ countries of origin suffers from a great loss of data because in some countries, such as the U.S., data on country of origin has not been collected. This results in a regrettable loss of efficiency when macro-indicators are included while countries drop off the sample because they provide no information on countries of origin. Furthermore, the survey is not well-suited to the study of immigrant integration. Nevertheless, our chapter provides valuable hints for further research and proves that the societal context of destination countries serves as a frame of reference and opportunity structure that has to be included in the analysis of immigrant integration processes.

Our results also show that research on the interplay between welfare state institutions and immigration and integration processes has to take into account the individual level in order to be able to distinguish the effects of specific institutions. Considering our results as well as previous research, it becomes obvious that immigrant integration is the result of complex processes. Even if the multidimensionality of individual social integration seems to be theoretically undisputed, empirical approaches often extrapolate from evidence of one dimension to other dimensions. We see that national institutions can have different or even contrary effects, even for one and the same dimension of integration. The institutional setting of liberal welfare states may have positive effects on labour market integration but negative effects on educational or residential integration. Furthermore, effects can vary across different immigrant generations. Our chapter corroborates the importance of a precise distinction of varying effects and findings in order to make reliable statements about the process of immigrant integration.

Notes

- 1.

This and the following figures are results of our own computations with PISA 2009 data.

- 2.

The theory of segmented assimilation considers social, political and societal conditions (“contexts of reception”) in relation with individual immigration experiences as decisive for the respective mode of incorporation and the chosen path of assimilation. For instance, government policy towards an immigrant group can be receptive, indifferent or hostile. Likewise, the attitudes of the host society can be free of prejudice or shaped by social distance (Portes and Böröcz 1989; Portes and Rumbaut 1990, p. 91).

- 3.

As a simplification we also assume full information for the utility of the status quo in the future.

- 4.

Programme for International Student Assessment.

- 5.

The competence scales are standardised to a mean of 500 points (OECD average), the standard deviation is 100.

- 6.

United Populations Division, International Migrant Stock 2008, http://esa.un.org/migration/index.asp?panel=1 accessed November 2011.

- 7.

The database comprised the proportional values for the ten biggest immigrant groups in a country. Source: Global Migrant Origin Database: http://www.migrationdrc.org/research/typesofmigration/global_migrant_origin_database.html, accessed November 2011.

- 8.

Both indicators from World Bank World Development Indicators: http://databank.worldbank.org/ddp/home.do?Step=2&id=4&DisplayAggregation=N&SdmxSupported=Y&CNO=2&SET_BRANDING=YES, accessed November 2011.

- 9.

The range of reading achievement is defined as the difference between the 95th and 5th percentile of the reading score distribution. .

- 10.

http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=5401, accessed November 2011.

- 11.

See http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/59/32/39730315.pdf for the derivation of the adjusted individual weighting variable, accessed November 2011.

- 12.

The threshold for the second proficiency level in reading corresponds to 407.47 points on the reading scale (PV1READ to PV5READ). Thus, our dependent variables are five dummy variables that indicate if the pupil’s plausible values are below this threshold.

References

Alba, R., and V. Nee. 1997. Rethinking assimilation theory for a new era of immigration. International Migration Review 31(4): 826–874.

Alba, R., and V. Nee. 2003. Remaking the American mainstream. Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Banting, K.G., and W. Kymlicka (eds.). 2006. Multiculturalism and the welfare state. Recognition and redistribution in contemporary democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Becker, G.S. 1993. Human capital. A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Becker, R. 2000. Klassenlage und Bildungsentscheidungen. Eine empirische Anwendung der Wert-Erwartungstheorie. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 52(3):450–474.

Boeri, T., G. Hanson, and B. McCormick (eds.). 2002. Immigration policy and the welfare system. A report for the Fondazione Rodolfo Debenedetti. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bommes, M., and A. Geddes (eds.). 2000. Immigration and welfare. Challenging the borders of the welfare state. London: Routledge.

Borjas, G.J. 1990. Friends or strangers. The impact of immigrants on the U.S. economy. New York: Basic Books.

Borjas, G.J. 1994. The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature 4: 1667–1717.

Boudon, R. 1974. Education, opportunity, and social inequality: changing prospects in western society: L’ inégalité des chances engl. New York: Wiley & Sons.

Breen, R., and J.H. Goldthorpe. 1997. Explaining educational differentials: towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society 9(3): 275–306.

Breton, R. 1964. Institutional completeness of ethnic communities and the personal relations of immigrants. American Journal of Sociology 70(2): 193–205.

Buchmann, C., and E.A. Parrado. 2006. Educational achievement of immigrant-origin and native students: A comparative analysis informed by institutional theory. In The impact of comparative education research on institutional theory, ed. D.P. Baker, 345–377. Amsterdam: Elsevier JAI Press.

Entorf, H., and N. Minoiu. 2004. What a difference immigration law makes. PISA results, migration background and social mobility in Europe and traditional countries of immigration. ZEW Discussion paper 04–17. Mannheim.

Erikson, R., and J.O. Jonsson. 1996. Introduction: Explaining class inequality in education: The Swedish test case. In Can education be equalized? The Swedish case in comparative perspective, ed. R. Erikson, and J.O. Jonsson, 1–63. Boulder: Westview Press.

Esser, H. 1999. Soziologie, Bd. 1: Situationslogik und Handeln. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

Esser, H. 2006. Sprache und Integration. Die sozialen Bedingungen und Folgen des Spracherwerbs von Migranten. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

Esser, H. 2008. Assimilation, ethnische Schichtung oder selektive Akkulturation? Neuere Theorien der Eingliederung von Migranten und das Modell der intergenerationalen Integration. In Migration und Integration. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie Sonderheft 48, ed. Kalter F., 81–107. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Goldstein, H. 2003. Multilevel statistical models. London: Arnold u.a.

Hinz, T, Zerger, F., and J. Groß. 2004. Neuere Daten und Analysen zur Bildungsarmut in Bayern. Forschungsbericht.

Kogan, I. 2006. Labor markets and economic incorporation among recent immigrants in Europe. Social Forces 85(2): 697–722.

Koopmans, R. 2010. Trade-offs between equality and difference: Immigrant integration, multiculturalism and the welfare state in cross-national perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36(1): 1–26.

Levels, M., J. Dronkers, and G. Kraaykamp. 2008. Immigrant children’s educational achievement in western countries: Origin, destination, and community effects on mathematical performance. American Sociological Review 73(5): 835–853.

Luke, D.A. 2004. Multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Marks, G.N. 2005. Accounting for immigrant non-immigrant differences in reading and mathematics in twenty countries. Ethnic and Racial Studies 28(5): 925–946.

Mood, C. 2010. Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review 26(1): 67–82.

Morissens, A., and D. Sainsbury. 2005. Migrants social rights, ethnicity and welfare regimes. Journal of Social Policy 34(4): 637–660.

Nannestad, P. 2007. Immigration and welfare states: A survey of 15 years of research. European Journal of Political Economy 23(2): 512–532.

Park, R.E. 1950. The collected papers. Volume 1: Race and culture. Glencoe: Free Press.

Portes, A., and J. Böröcz. 1989. Contemporary immigration. Theoretical perspectives on its determinants and modes of incorporation. International Migration Review 23(3): 606–630.

Portes, A., and R.G. Rumbaut. 1990. Immigrant America. A portrait. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Portes, A., and R.G. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies. The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley: University of California Press, Russell Sage Foundation.

Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96.

Schnepf, S.V. 2007. Immigrants’ educational disadvantage: An examination across ten countries and three surveys. Journal of Population Economics 20(3): 527–546.

Snijders, T.A.B., and R.J. Bosker. 1999. Multilevel analysis. An introduction to basic and advanced modeling. London: Sage Publications.

Solga, H. 2009. Bildungsarmut und Ausbildungslosigkeit in der Bildungs- und Wissensgesellschaft. In Lehrbuch der Bildungssoziologie, ed. Becker R., 395–432. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Stanat, P. and G. Christensen. 2006. Where immigrant students succeed. A comparative review of performance and engagement in PISA 2003. Paris: OECD.

United Nations 2010. World population policies 2009. New York: United Nations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Teltemann, J., Windzio, M. (2013). Socio-Structural Effects on Educational Poverty of Young Immigrants: An International Comparative Perspective. In: Windzio, M. (eds) Integration and Inequality in Educational Institutions. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6119-3_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6119-3_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-6118-6

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-6119-3

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)