Abstract

This chapter draws on a collective case study of doctors’ learning in transition to show that different ways of explaining learning in practice (e.g. situated learning and learning cultures) cannot fully account for what happens when doctors make these transitions. We develop Hodkinson, Biesta and James’ (Vocations and Learning 1:27–47, 2008) theories of learning cultures and cultural theories of learning in two ways to help us understand learning in transition. First, we draw on Thévenot’s (Pragmatic regimes governing the engagement with the world. In Schatzki TR, Knorr Cetina K, von Savigny E (eds) The practice turn in contemporary theory. Routledge, London, 2001) notion of pragmatic regimes of practice to show how most approaches to doctors’ learning focus on the public regimes of justification and regular action; transitions, however, always involve regimes of familiarity which are usually ignored in theorising their learning. Second, we introduce our notion of doctors’ transitions as critically intensive learning periods, in order to explain the interrelationships between learning, practice and regimes of familiarity. We ground our discussion in three scenarios to illustrate how practice always involves the socio-material world. We examine the theoretical and practical implications, particularly in respect of learning local practices or, as Thévenot would say, learning regimes of familiarity.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

The challenge set by the editors of this book is to investigate the role and significance of learning in conceptualising practice. They ask us specifically how different theories of learning expand, or restrict, understandings of practice in the context of specific empirical and conceptual investigations. In order to address these questions, we draw on our research about doctors’ learning in transitions to new levels of responsibility. We are interested in theorising doctors’ learning in transition generally and their learning to make transitions specifically, not least because such transitions are more frequent and critical in medicine than in many other professions: they form an essential feature of doctors’ careers. They are also of particular concern because, during the transition, we would expect, and indeed have found, that learning in authentic practice is in the foreground; doctors working on hospital wards are expected to care for patients from the moment they enter the transition.

Beginning with an explanation of the context for doctors’ learning and an outline of the underlying assumptions about learning policy in this arena, this chapter will draw on a collective case study of doctors’ learning in transition to show that different ways of explaining learning in practice (e.g. situated learning and learning cultures) cannot fully account for what happens on the ward. Although Hodkinson et al.’s (2008) theories of learning cultures and cultural theories of learning were helpful in developing an alternative understanding of learning in transition, we have identified the need to develop further ideas to theorise practice. We suggest how this might be done in two ways. First, we will draw on Thévenot’s (2001) notion of pragmatic regimes of practice to show how most approaches to doctors’ learning focus on the public regimes of justification and regular action; transitions, however, always involve regimes of familiarity which are usually ignored. Second, we will introduce our notion of doctors’ transitions as critically intensive learning periods, in order to explain particularly the interrelationships between learning, practice and regimes of familiarity.

In order to ground the discussion, three specific scenarios will be explored: clinical practice with people, with people and artefacts and with artefacts. These examples also serve to illustrate how practice involves animate and non-animate actors and how non-animate actors are not just background or contextual features but centrally implicated in practice. We will use our analysis and interpretation of these scenarios to examine the theoretical and practical implications, particularly in respect of learning local practices (regimes of familiarity). The case study will also make a contribution to our understanding of the role of learning culture in supporting the integration of practice as both service and learning.

Understanding Doctors’ Learning

Dominant Assumptions About Doctors’ Learning

Internationally, training for initial registration as a doctor is university based; doctors are then required to work, whilst undertaking further training, before they can be licensed to practice independently as a hospital consultant or general practice principal (family doctor). In the UK, newly registered doctors are enrolled in a 2-year foundation programme (designed to provide generalist training); subsequently, trainees enter specialty training for at least 3 years. Each stage of training has a structured programme with formalised requirements which include explicit expectations that trainees will have clinical training in a range of practices and procedures and regular, formal educational sessions. Trainees are required to have a designated educational supervisor, to sign a training/learning agreement at the start of each post and to maintain a logbook and/or a learning portfolio.

A number of implicit assumptions about learning emerge from this brief outline of the pedagogic support for doctors. First, learning tends to be understood mainly as a cognitive process (Sfard 1998; Saljö 2003; Mason 2007). For example, the notion of ‘preparedness’ for practice is prevalent throughout the medical education literature (Lempp et al. 2004, 2005; Illing et al. 2008; Nikendei et al. 2008; Matheson and Matheson 2009; Cave et al. 2009) in the formal training requirements, in employers’ practices and amongst education providers. Whilst there is recognition that learning is facilitated by practice, the notion of preparedness separates learning from practice because it privileges learning as occurring before and outside practice.

Second, context is seen as separate from the learner with the learner enveloped by context (Edwards 2009). Issues of work organisation, power and wider social and institutional structures are generally excluded from consideration (e.g. Unwin et al. 2009). This critique may be taken one step further: because learning is seen as an individualistic, internal and mostly cognitive process, people and artefacts (the socio-material world) are also separated from the learner and learning/knowledge-making processes (Nespor 1994; Knorr Cetina 2001; Fenwick and Edwards 2010). This both ignores learning as an embodied process with practical, physical and emotional aspects as well as cognitive ones and fails to take into account the claim that learning in practice and elsewhere is relational. Consequently, the response to any problems with doctors’ transitions almost always focuses on more and better ‘preparedness’ (located within the doctor) and rarely considers the material and social world of practice.

Situated Learning, Apprenticeship and Communities of Practice

In contrast, socially derived understandings of learning within the work environment emphasise practice as the basis for learning. There are many versions of these understandings, but within medical education, Lave and Wenger’s (1991) work on situated learning is most frequently cited (e.g. Bleakley 2005; Dornan et al. 2005). In this account, learning is viewed as engagement in legitimate peripheral practice under the guidance of experienced practitioners. Learning is understood as a form of ‘becoming’ in which knowledge, values and skills are not separate from practice. However, as we found in conceptualising our research, there are immediate problems when these ideas are used to explain doctors learning, particularly during transitions.

First, the transition itself is not an apprenticeship; there is frequently a disjunction between one level of responsibility and another; for example, overnight upon qualification, doctors acquire the responsibility to prescribe. Second, responsibility does not necessarily increase in a linear fashion through transitions and over time; levels of responsibility vary between settings and specialities, and a trainee may find they have less, rather than more, independence in some settings than others, despite being more experienced in terms of time served post qualification. Furthermore, legitimate responsibility may change significantly depending on other factors such as the time of day (night) and/or who else is present – if the most experienced practitioners are absent, trainee doctors are no longer peripheral participants but full members.

There are other aspects of practice which do not fit Lave and Wenger’s notion of apprenticeship. Clinical teams (to which doctors belong) are not stable communities because the structure of much clinical practice involves shift working and other changing work patterns. Further, clinical workplaces are populated by intersecting – even competing – communities of professionals (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, other health-care workers). There may also be competing values and practices between old-timers and newcomers, as newcomers bring changing practices with them. Finally, practices themselves transform constantly, whether because of changes in policy and regulation, technological transformation or responses to evidence; hence, the notion of an old-timer in relation to these new practices may be questionable. Thus, whilst it is clear that doctors’ learning and practice in transition are inseparable, the understandings derived from the literature on communities of practice do not account for the particularities of clinical practice. This critique also has resonance for practice in other professions where service demands of newcomers require high levels of performance and responsibility.

Theories of Learning Cultures and Cultural Theory of Learning

We initially turned to Hodkinson, Biesta and James’ (2008) theory of learning cultures to formulate and interpret our research. They argue that most situated learning theorists focus on either a theory of learning cultures, or a cultural theory of learning. They also argue that we need both theories in order to circumvent some of the dualisms (e.g. mind/body and individual/social) which occur in the literature. This argument attracted us to their ideas.

Learning cultures are not equated with learning location but are understood as ‘the social practice through which people learn’ (Hodkinson et al. 2008:34). Such practices are constituted by the actions, dispositions and interpretations of participants in a reciprocal process in which ‘Cultures are (re)produced by individuals just as much as individuals are (re)produced by cultures, although individuals are differently positioned with regard to shaping and changing a culture …’ (p. 34). So, for example, different wards have very different ‘feels’ for new participants, constituted through the social practices on the wards; different participants ‘fit’ specific learning cultures to a greater or lesser extent.

Learning cultures are not ephemeral: they have histories and endurance through a range of phenomena. Hodkinson et al. suggest they function through the actions of individuals who themselves operate through ‘systems of expectations’ (p. 34) – that is, the expectations they bring to the learning culture and the expectations that others have both of the learning culture and of them. Importantly, Hodkinson et al. contribute the concept of ‘scale’ (p. 34) in the consideration of learning cultures. By scale, they mean the different levels of measurement used in map making; research is often focused at one scale or another – the ward in our case; but the notion of learning culture invokes much more than the specific ward – in considering our doctors’ learning in transition, we also have to take into account the specialty, the hospital, the Trust, the National Health Service, the field of healthcare more generally and so on. And of course, learning culture is also affected by macro-political fields and power broking by, for example, health policies including targets, the economic interests of the pharmaceutical industry and private healthcare; and all interpenetrated by gender, class, ethnicity, sexuality, etc.

Turning now to a cultural theory of learning, Hodkinson et al. (2008) suggest that the individual is not just ‘jetted in’ to the learning culture (as implicit in dominant perspectives in medical education). Instead, they are part of the field too. Individuals both influence and are part of learning cultures just as learning cultures influence and are part of individuals. Learning therefore exists in and through interaction, participation and communication in the learning culture. Drawing on Bourdieu’s (1977) concept of habitus, they argue that the impact of each individual within the learning culture depends on a combination of their position within the culture, their dispositions towards the culture and various types of capital (social, economic, cultural) possessed by individual and valued in relation to the field (which operates at the scale of individual interactions as well as at the macro-scales described above). (However, certain conditions in the field can determine the impact of the individual over and above their position, dispositions and capital. For example, understaffing on a ward might necessitate a much quicker immersion of the trainee in responsible practice, regardless of who they are.)

Finally, Hodkinson et al. (2008) argue that each individual has their own horizons for learning which are not fixed but are relational. Opportunities to learn depend on the nature of the learning culture and individual’s position, disposition and capitals in interaction with each other. In summary, Hodkinson et al. argue that a person learns through becoming and becomes through learning. Such learning may be deliberative with explicit purpose, and/or it may be contingent, but learning as becoming transcends individual situations and learning cultures. Nevertheless, it is always situational.

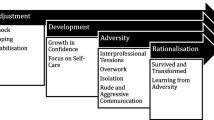

Conceptualising the Transition Itself: Going Beyond Learning Cultures and a Cultural Theory of Learning

Doctors’ work and training is characterised by frequent transitions between levels, sites, specialty, etc., which disrupt somewhat this metaphor of ‘becoming’. For example, each time a doctor moves to a new setting and is immersed in a new learning culture, there is a process of unbecoming because the relationship between habitus and field is dynamic, not unidirectional – capitals may decrease as well as increase. For example, in elderly medicine, where patients’ conditions are often complex, trainees in transition to (and from) this speciality frequently find they need to revise their clinical practices accordingly. This could be explained by the concept of horizons for learning, but it does not adequately account for the intensity of clinical settings and clinical practice which demand a more nuanced approach to the relationship between learning and specific practices.

Particular issues about the socio-material also need addressing. Medical practice encompasses notes, files, machines, bodily fluids, patients, drugs and stethoscopes. Although these are acknowledged as part of the learning culture, and learning is regarded as embodied, practical and social, artefacts and other material aspects of practice remain theoretically in the background, whilst participation and communication is foregrounded. Other accounts of learning and practice from the actor-network theory stable (e.g. Nespor 1994) would not privilege the human over the non-human actors in this way.

Other features of doctors’ learning in transition need to be taken into account. First, there is an indeterminate time frame during which an individual is able more or less successfully to become part of the field; this involves being able to act in concert with the learning culture and being able to influence it in minor ways. If, within that time frame, an individual does not appear to have learnt sufficiently well, their horizons for learning will be curtailed. For example, nurses will not ask trainees to carry out certain procedures or to intervene with patients if they think they are not ‘safe’. The less nurses ask of trainee doctors, the fewer chances there are to learn in practice. Second, because the focus of learning is usually patient-centred, other aspects of the learning culture (relationships with others, work processes, practical issues) may be opaque and/or even invisible for new doctors in transition. Some doctors are much better at making transitions because they have come to understand the significance of the first few hours/days/weeks working with others. Third, because it is assumed that learning is cumulative and that the more transitions a doctor has made, the more they are likely to have ‘become’, in some specialties and certainly after the first transition or two, little allowance may be made in the practice setting for ‘becoming’. Fourth, understandings about ‘horizons for learning’ are helpful but do not articulate the intensity, urgency and time-bound nature of transition periods in clinical settings.

We therefore conceptualise doctors’ transitions as critically intensive learning periods (CILPs) to draw attention to these issues. We use the term ‘critical’ in the sense of ‘critical period’, a term derived from developmental psychology which refers to a limited time in which some event can occur, usually resulting in some kind of transformation; by ‘intensive’, we mean to suggest the immediacy invoked by the immediate requirement to deliver patient care; and by ‘learning’, we mean ‘an integral part of generative social practice’ (Lave and Wenger 1991: 35). The trajectory of the CILP for a doctor transitioning to a new ward is dependent, not only on the interrelationships between habitus and learning culture, but also on the practices of the learning culture in relation to transitions and the doctor’s own understanding of the transition as a learning period. Most importantly, doctors’ primary focus in practice is on patient care; this heightens the pressure on doctors who know that all their (in)actions have the potential for harm. This moral dimension is crucial – and the reason why we turned to Thévenot’s (2001) ideas about pragmatic regimes of practice. These enable us to refine our understanding such that the trajectory of a specific CILP is dependent on a dynamic relationship between different pragmatic regimes and to attend to moral and socio-material elements of the transition.

Pragmatic Regimes

Thévenot (2001) recognises the usefulness of the concept of ‘practice’ which he defines as embodied, situated and shaped by habits without reflection; he contrasts this with models of ‘rationally calculated action’ (p. 56). However, he argues that the very breadth of the concept of practice is a problem because it makes it difficult to elaborate different types of agency. For him, there are two main problems with theories of practice such as Bourdieu’s: they do not provide ‘good accounts of our dynamic confrontation with the world’ (p. 56) nor do they account for the moral element in practice which ‘shapes the evaluative process governing any pragmatic engagement’ (p. 57).

Thévenot accounts for the dynamic aspects of practice – movements of actors, the ways the environment responds and ways actors take this into account – with the notion of pragmatic regimes. He argues that some force – values, norms, beliefs, interests and dispositions – ‘some conception of the good’ (p. 59) exists which differs from one regime to another although all regimes are grounded on a notion of the good. This moral element is critical because it both drives the agent in their conduct and determines how other agents make sense of this conduct. Thévenot is concerned with practice which is not regular and stable (as is the case in clinical settings, particularly in transitions); his concern with the dynamics of material engagement and the moral element of practice offered us a way of accounting for the imperative of patient care within accounts of learning.

Pragmatic regimes are different ways of engaging with the world in practice. Thévenot employs an engaging and thought-provoking example of how we inhabit our spaces to explain the notion of pragmatic versatility or different modes of engagement with the environment. Imagine a room in one’s home which we inhabit in ways of ‘personal and local convenience’. For example, we might place items on the stairs to remind us of something, or we might use a chair to house our clothes. He suggests that this involves both body and environment – the human and the non-human – for our local convenience. Someone else seeing our usages might think them strange, but after a whilst, they might adopt the practice as their own in a process which ‘involves weaving and extending the web of all these idiosyncratic linkages with an entourage’. Such usages can be difficult to speak about because they are so embodied.

Now consider inviting someone to do a house swap. We would have to tidy up the reminders on the stairs, the clothes on the chair, despite their usefulness. We have to exchange our idiosyncratic local conveniences for ‘conventional utility’. This ordering might not accord with what others do – for example, our grocery supplies, whilst orderly, may not be stored within the same categories as others – but now everyday language suffices for such arrangements.

Next, consider renting one’s house: suddenly we need a better understanding of ‘good working order’. We are subject to different tests applying to different things – say, gas appliances or smoke alarms – terms such as defect and misuse become conventionalised through legislation and other formalities. Thévenot calls these legitimate conventions of qualification.

These three forms of pragmatic versatility map onto different pragmatic regimes or particular ways of engaging with the environment: they ‘…govern our way of engaging with our environment inasmuch as they articulate two notions: a) an orientation towards some kind of good; b) a mode of access to reality’ (p. 67). Thévenot defines three main regimes: familiarity, regular action and the public regime of justification.

Within a regime of familiarity, human and non-human capacities are intertwined. In the same way as possessions on the stairs serve as an extension of human memory – as a visual reminder fashioned by personal use – artefacts and people are enmeshed through historical practice in an ‘accustomed dependency with a neighbourhood of things and people’ (p. 68), for personal and local convenience. Thévenot says that such a regime, whilst social, moves us away from an orientation towards others; instead, it invokes the material. He argues that, whilst Bourdieu (1977) was interested in the familiar, his notion of habitus (and subsequent ideas) omitted any consideration of the ‘personalised and localised dynamics of familiarity’ (Thévenot 2001: 66). Similarly, Hodkinson et al.’s (2008) theories can be criticised for underdeveloping socio-materiality in practice.

A regime of regular planned action, in contrast, involves both agents and the world in a ‘joint elaboration of both intentional planning agency and instrumental-functional capacity’ (p. 70) such that we move away from the classical view that agents are the only elements with planning capacities. Instead of thinking about ‘good’ as located within human action alone, this enables to understand that pragmatic requirements sustain individual agency– ‘it is the good of a fulfilled planned action’ (p. 70).

A public regime of justification entails collective conventions of the legitimate common good (smoke alarms installed) in some kind of codified way. The ‘qualified’ person who engages in a codified regime is the agent of practice. By qualification, Thévenot means that people and things have to have certain capacities that can be tested in relation to different orders of worth.

Returning now to our doctors, we will argue that these concepts serve two functions: first, they enable us to speak in more detail about the dynamics of practice, and, second, we can now understand why most approaches to doctors’ transitions falter. The regime of familiarity is under-recognised. Instead, the focus is on public regimes of justification and regular action, as illustrated in the requirements for doctors’ training outlined earlier.

We will now summarise our study to show how doctors’ transitions always involve regimes of familiarity and then focus on three scenarios which show how regimes of familiarity may involve artefacts, people and people with artefacts.

Background to the Study

The original study (Learning responsibility? Exploring doctors’ transitions to new levels of medical performance) sought to understand the links between transitions and medical performance both empirically and conceptually (Kilminster et al. 2010). Briefly we drew on Stake (2005) to develop a ‘collective’ case study of doctors in order to focus on the interrelationships between individual professionals and complex work settings and to take into account the layers of complexity and diversity. We analysed relevant regulatory and policy requirements in order to understand the case study contexts. We then investigated aspects of transition at four regulatory levels – the individual, their clinical team (and the site in which they were located), their employer and the regulatory and policy context. We used a combination of desk-based research, interviews and observations. We focused on two main points of transition: from medical student to foundation training (F1) when doctors begin clinical practice (see above) and from foundation training or generalist training to specialist clinical practice/specialist training (ST).

We concentrated our study on doctors working in elderly medicine because it involves complex patient care pathways and decision making. Drawing on the same specialty across the study also facilitated exploration of the significance of differing individuals and differing local working practices, within broadly similar overall contexts. This maximised the strengths of the case study approach. Participants were based in six UK hospitals (two university teaching hospitals and four district hospitals).

We conducted focused interviews with 10 F1 doctors (9 women and 1 man) and 11 STs (7 women and 4 men) near the point of transition; most participants completed a second interview 2–3 months later. As well as interviewing, we invited participants to be observed on the ward, near the beginning of the transition, but after the first interview. Whilst F1 doctors were willing to be interviewed, they were reluctant to be observed in practice, possibly because they lacked confidence in having their performance/work scrutinised. In contrast, most STs were willing to be observed. Because STs frequently work with F1 doctors, we were able to make some indirect observations of F1s. We undertook 13 supplementary interviews with professionals in elderly care working with F1s and STs in the study sites.

Three Scenarios

Regimes of Familiarity: Artefacts

Extract from observation notes:

It is 8.10 p.m. This is Sarah’s second night on the elderly admissions ward … she tells me that she had not had any induction the night before, nor received any paperwork. A nurse turns up and asks Sarah her name. Sarah goes to see her first patient (a job handed over from the earlier shift), consults with the Nurse, and then takes a blood sample from the patient. We [researcher and Sarah] go off to get blood analyzed in a nearby room. Sarah explains that the night before she could not find the machine and was banging doors open and shut; she also spoke about how some machines on other wards had passwords protecting them, making it impossible for new users.

The patient’s results were ‘all over the place’; Sarah was convinced that the problem was the machine, rather than the patient, because she had a similar problem on her first night the day before; she consulted the registrar (senior doctor) who had arrived on the ward, and decided that we needed to find another machine. We ran down corridors and stairs to the Accident and Emergency department of the hospital where she had worked in her previous rotation; she therefore knew the password. We ran because bloods need to be analyzed within a short window after they’re taken. The results looked much better.

Regimes of Familiarity: People

Jane, working at ST level, was a general practice trainee undertaking her hospital-based training. She had recently made the transition to working on an elderly medicine ward at a District hospital with numerous organisational and staffing problems. Working conditions on this new ward were particularly difficult because one of the consultants was off sick ‘so we’ve all had to group together’ and ‘we’re just trying to get through each day.’ Jane was acutely aware that they had a relatively junior team of doctors and that she was the most experienced of that team; although she felt more confident talking to families, she did not feel sufficiently knowledgeable in terms of elderly medicine. Jane had thought a lot about transitions because she really did not like making them and believed they had negative effects on relationships. She talked about how, on her first day on the ward, she had seen a lot of patients on her own to help ‘conquer the fear’; for her, actually engaging in clinical practice was a relief.

Jane knew in advance that this ward was quite disorganised because she had spoken to the person who had been doing her job previously who had ‘absolutely hated it’. Jane had therefore concentrated on establishing relationships:

I made an active effort to go and introduce myself if I’d not seen someone’s face before. Especially the nurses because I definitely think it … gets you off on the right track and they are more likely to give you respect if you respect them. They are used to having so many different doctors as well. So I think if you say I replaced so and so this is who I am then they know my name; they are asking me to talk to families. They are treating me totally as if I’ve probably always been there. (Emphasis added; Interview 1)

As Jane had been warned, the ward was particularly disorganised so that, during her third day, Jane realised she did not know which doctors were present and which patients they had seen: ‘I felt quite unnerved about it’. Jane worked with the other doctors to develop some organisation:

I found what I like to do is I like to decide between us what everybody is doing and to know what everybody is doing – as in who is in that day? How many patients have we got to see? Then we can join together and we can do a plan. (Interview 1)

Jane was observed about a month later. By now she had established strong relationships with two other doctors who liked to work together: ‘we are on each other’s wavelength’. There was another doctor present who did not fit easily in this team and who was left to go and see the outliers (patients on other wards in the hospital). During the morning, the three doctors, the physiotherapists and the occupational therapist working on the ward frequently met together at a whiteboard with all the patients’ names on it. As they consulted the whiteboard and talked, they generally exchanged information about the patients. However, on this ward, the nurses were conspicuous by their absence both physically and on the board. There were some problems with nursing care, and the board to indicate which nurse was working with each patient was empty; the other professionals all worked around this.

Regimes of Familiarity: People with Artefacts

Sam, an ST, who had started that week on the ward, explained when I arrived that he was looking for a kit to drain someone’s chest. The patient was an outlier and therefore ‘his’ responsibility, so he was going to be carrying out the procedure on another ward. He went into a room full of equipment and asked a nurse there for the appropriate kit. A second nurse became involved in searching. A consultant from the ward arrived and, seeing that the nurse she wanted was involved in a search, asked what Sam was looking for. When he explained, she said that they usually made a home-made ‘kit’ to do the same procedure, describing how it would work. Sam asked several questions to clarify, and then began to gather up some of the necessary equipment.

When we arrived on the patient’s ward, with which Sam was not familiar, Sam found some of the equipment he needed already set out on a trolley in the corridor. He went into the sluice room to prepare a bit further and a nurse came in scolded him, saying that he shouldn’t prepare in such an unhygienic environment. When he asked where he should prepare instead, he was told that, on this ward, preparations usually took place in the corridor. (Taken from observation notes)

Understanding Regimes of Familiarity

These scenarios show how regimes of familiarity operate in relation to individual doctors’ transitions. In the first instance, Sarah ‘worked around’ the unsatisfactory blood readings she obtained from the ward machine and the problems of password-protected systems by finding another machine with which she was already familiar. This machine was some long way away but already part of Sarah’s practice. In the second instance, Jane found ways of engaging with both fellow doctors and with nurses to ensure better organisation and integration within the idiosyncratic practices of that specific ward. In the third, Sam found himself immersed in an unfamiliar world of practice assembling artefacts (chest kits) and spaces (sluice rooms and corridors) to come to grips with regimes of familiarity. These examples enable us to develop a more nuanced understanding of doctors’ transitions, particularly in respect of learning. The pragmatic versatility of these regimes of familiarity is significant in practice: and a doctor’s ability to negotiate such regimes dictates not only whether or not they are able to care adequately for patients but also how they will be judged by others.

For relatively long-standing professionals (and artefacts) on the ward, everyday practice is settled practice with regimes of regular action and familiarity operating implicitly. New doctors in transition, although a regular occurrence, unsettle that practice. There are, of course, expectations that doctors should be familiar with (‘prepared for’) life on the ward. Some of these expectations are formalised in the requirements of the regulatory bodies, education providers and employers – the public regime of justification. And clinical teams expect to familiarise doctors with regular planned action such as care pathways or other explicit aspects of local practice. There is some recognition of learning in transitions, although it is very much concerned with the public regime of justification, for instance, in requirements about health and safety training, trust training for basic life support, protocols and so on. But, as our three scenarios show, day-to-day practice involves regimes of familiarity which are harder to disclose or talk about because they are accretions of accommodations, work-arounds, idiosyncracies, avoidances and so on. Crucially, some regimes of familiarity may contradict public regimes of justification. For example, the preparation of clinical equipment in an open corridor would contravene infection control regulations. Also, as for those storing their reminders on the stairs, such ‘local conveniences’ can be difficult to identify because they are so embodied and embedded in practice.

Trainees, too, need to be able to insert themselves into these ever-changing regimes. In the second example above, Jane understood this as she showed in her comments about being recognised and asked by the nurses to take on tasks; her engagement in the local practices also afforded her further opportunities to develop her practice. However, Jane’s colleague who was manoeuvred into working with ward ‘outliers’ because he did not fit in to the local team had fewer opportunities to learn the local practices and thus to make a successful transition. Sam did not pick up on the local practice of preparing clinical equipment on a trolley in the corridor and complained about the fact that he had to prepare a chest drain kit, rather than being given a complete package.

But trainees need also to develop their own practices which are able to accommodate other regimes of familiarity: Sarah quickly worked around the problem of the local ward machinery when she realised it did not work (although why she had not reported its malfunction the night before is mysterious). Her actions were embedded in her historical relations with the artefacts for analysing blood. And Jane realised that, if the ward was disorganised, she would have to invent her own routines to ensure that patients were seen efficiently. These examples demonstrate that as well as learning in transition, trainees have to learn to make transitions. Jane, in particular, demonstrated her own pragmatic versatility to respond to her dislike of making transitions.

So, to return to the relationship between the trajectories of CILPs and these pragmatic regimes, although public regimes may be learnt beforehand (ideas about preparedness and education for practice can encompass the public regime very well), and to a lesser extent even regimes of regular action can be made explicit for new arrivals (‘this is how we do it here’), there is no way around the necessity of learning regimes of familiarity in practice. The moral purpose – the good governing the interaction – does not change but its manifestation does.

Conclusions

Implications for Understanding CILPs

We have tried to show that our conceptualisation of transitions as CILPs is important for several reasons. First, small actions during the CILP are often treated as symbolic of a trainee’s ability to carry out tasks. Those small actions often require trainees to have picked up on (‘learnt’) the regimes of regular action and familiarity speedily; the more they seem to have done this, the more they are afforded new opportunities for learning. But the more experienced the doctor, the less leeway they have to learn ‘how we do things round here’, sometimes being expected to practise immediately without any period for learning.

Second, the intensity of the CILP comes about not only because of the pressure of clinical care which cannot be overemphasised but also because others need quickly to make judgements about capability in order to assure patient safety. The CILP might involve the introduction of new regimes, as in the example above of Jane ‘getting organised’. Third, the extent to which the specific learning cultures of the clinical workplace (at ward and at institutional levels) recognise transitions as CILPs contributes to or inhibits the performance of new doctors. Some aspects of the CILP are sometimes recognised and institutionalised in practice in a few specialties such as emergency medicine due to specific working practices and expectations. This involves a markedly different learning culture from the ones we witnessed within elderly wards and suggests that a different approach is possible. Of course, on some wards, some aids to learning were offered – handbooks, for example, or being shown around. But this was not, by any means, standard.

Implications for Understanding Learning and Practice

Existing ways of thinking about practice do not suffice when it comes to doctors. Although all practice is governed by some notion of ‘good’ as Thévenot argues, some practices – doctors’ for example – may be more highly charged than has been written about in much of the literature. Further, whether or not junior doctors are treated as newcomers in their transitions to new areas of work and levels of responsibility, the nature of the work itself and the conditions for work mean that such doctors may at times have to be experts, required to act with full responsibility in the absence of expert others. Whilst the problem has been recognised by developing the notion of ‘preparedness’, this does not suffice, because the idea relies on an underlying conceptualisation of the trainee doctor as a cognitive, a social, a historical being. Here, we have shown that clinical practice involves different pragmatic regimes: familiarity, regular action, and justification. Transitions which involve doctors caring for patients necessitate engagement with all three regimes. The regimes of familiarity on which we have concentrated are relational in that new doctors have to be accommodated and new doctors have to accommodate other people’s regimes of familiarity. There is no preparation for such accommodation, although learning that such regimes exist – that such accommodation is to be expected – would certainly contribute to a better understanding of learning in transition.

Endnote

This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council in the UK as part of a larger programme of research part-funded by the General Medical Council (ESRC RES-153-25-0084).

References

Bleakley, A. (2005). Stories as data, data as stories: Making sense of narrative inquiry in clinical education. Medical Education, 39(5), 534–540.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cave, J., Woolf, K., Jones, A., & Dacre, J. (2009). Easing the transition from student to doctor: How can medical schools prepare their graduates for starting work? Medical Teacher, 31(5), 403–408.

Dornan, T., Scherpbier, A., King, N., & Boshuizen, H. (2005). Clinical teachers and problem-based learning: A phenomenological study. Medical Education, 39(2), 163–170.

Edwards, R. (2009). Life as a learning context? In R. Edwards, G. Biesta, & M. Thorpe (Eds.), Rethinking contexts for learning and teaching: Communities, activities and networks. Abingdon: Routledge.

Fenwick, T., & Edwards, R. (2010). Actor-network theory in education. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hodkinson, P., Biesta, G., & James, D. (2008). Understanding learning culturally: Overcoming the dualism between social and individual views of learning. Vocations and Learning, 1, 27–47.

Illing, J., Morrow, G., Kergon, C., Burford, B., Peile, E., Davies, C., Baldauf, B., Allen, M., Johnson, N., Morrison, J., Donaldson, M., Whitelaw, M., & Field, M. (2008). How prepared are medical graduates to begin practice? A comparison of three diverse UK medical schools: Final summary and conclusions for the GMC Education Committee. London: General Medical Council.

Kilminster, S., Zukas, M., Quinton, N., & Roberts, T. (2010). Learning practice? Exploring the links between transitions and medical performance. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 24(6), 556–570.

Knorr Cetina, K. (2001). Objectual practice. In T. R. Schatzki, K. Knorr Cetina, & E. Von Savigny (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory. Abingdon: Routledge.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lempp, H., Cochrane, M., Seabrook, M., & Rees, J. (2004). Impact of educational preparation on medical students in transition from final year to PRHO year: A qualitative evaluation of final-year training following the introduction of a new year 5 curriculum in a London Medical School. Medical Teacher, 26(3), 276–278.

Lempp, H., Seabrook, M., Cochrane, M., & Rees, J. (2005). The transition from medical student to doctor: Perceptions of final year students and preregistration house officers related to expected learning outcomes. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 59(3), 324–329.

Matheson, C., & Matheson, D. (2009). How well prepared are medical students for their first year as doctors? The views of consultants and specialist registrars in two teaching hospitals. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 85, 582–589.

Mason, L. (2007). Introduction: Bridging the cognitive and sociocultural approaches in research on conceptual change. Is it feasible? Educational Psychologist, 42(1), 1–7.

Nespor, J. (1994). Knowledge in motion: Space, time and curriculum in undergraduate physics and management. Philadelphia: Falmer Press.

Nikendei, C. B., Kraus, B., Schrauth, M., Briem, S., & Junger, J. (2008). Ward rounds: How prepared are future doctors? Medical Teacher, 30(1), 88–91.

Saljö, R. (2003). From transfer to boundary-crossing. In T. Tuomi-Gröhn & Y. Engeström (Eds.), Between school and work: New perspectives on transfer and boundary-crossing. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Sfard, A. (1998). On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educational Researcher, 27(2), 4–13.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Thévenot, L. (2001). Pragmatic regimes governing the engagement with the world. In T. R. Schatzki, K. Knorr Cetina, & E. von Savigny (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory. London: Routledge.

Unwin, L., Fuller, A., Felstead, A., & Jewson, N. (2009). Worlds within worlds: The relational dance between context and learning in the workplace. In R. Edwards, G. Biesta, & M. Thorpe (Eds.), Rethinking contexts for learning and teaching: Communities, activities and networks. London: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zukas, M., Kilminster, S. (2012). Learning to Practise, Practising to Learn: Doctors’ Transitions to New Levels of Responsibility. In: Hager, P., Lee, A., Reich, A. (eds) Practice, Learning and Change. Professional and Practice-based Learning, vol 8. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4774-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4774-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-4773-9

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-4774-6

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)