Abstract

This paper provides an overview of the contemporary debate on the concepts and definitions of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Corporate Sustainability (CS). The conclusions, based on historical perspectives, philosophical analyses, impact of changing contexts and situations and practical considerations, show that “one solution fits all” definition for CS(R) should be abandoned, accepting various and more specific definitions matching the development, awareness and ambition levels of organizations.

Notes

1World Commission on Environment and Development’s (Our Common Future, Brundland-1987): Sustainable development is the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

2Marsden and Andriof (1998) define good corporate citizenship as “understanding and managing a company’s wider influences on society for the benefit of the company and society as a whole”.

3Elkington (1997): “Triple Bottom Line” or “People, Planet, Profit”, refers to a situation where companies harmonize their efforts in order to be economically viable, environmentally sound and socially responsible.

4Kilcullen and Ohles Kooistra (1999): business ethics is “the degree of moral obligation that may be ascribed to corporations beyond simple obedience to the laws of the state” (p. 158).

5EU-Communication July 2002: “CSR is a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interactions with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis.”

6Quote in the Volkskrant: “Er zijn geen standaardrecepten: MVO is maatwerk”.

7See e.g. Göbbels (2002), Van Marrewijk (2001), Quazi and O’Brien (2000), Freeman (1984).

8With early contributions of McGuire (1963) and Committee for Economic Development – CED (1971), but also van Marrewijk (2001) and Gobbels (2002).

9Committee for Economic Development – CED (1971, p. 16).

10See also M. Foucault, The order of things (1970): “truth” is simply an arbitrary play of power and convention.

11Wilber, K., Sex, Ecology and Spirituality, 2nd ed. (Boston: Shambhala, 1995, 2000), pp. 19, 74.

12Wilber, K. SES (p. 28) italics by Wilber.

13Wilber, K. SES (p. 26).

14Koestler: “a holon is a whole in one context and simultaneously a part in another”.

15About 2.3 billion people live on less than $2 per day. The income of the top 20 in developing countries is 37 times the income of the bottom 20 and it has doubled in the last decade: See also Korten (2001), WRI, UNEP, WBCSD.

16See f.i. Drucker (1984), Hawken (1993), Elkington (1997), Zadek (2001).

17According to Wilber, consciousness (or awareness) is directly related to depth, i.e. the level in the hierarchy (p. 65).

18See also: Pirsig, R. Lila, an inquiry into morals (1991).

19Eli Goldratt during a lecture at RSM, October 1998.

20Wilber, K. SES (2000, p. 30).

21Henry Minzberg, at the inaugurating conference of the European Academy of Business in Society, Fontainebleau, 6 July 2002. “The economically oriented institutions such as the WTO, IMF and the Worldbank are not balanced by as powerful institutions, defending social and environmental interests.”

22Press release at 6 Sept 2002: www.account-ingweb.nl.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Supply Chain

- Civil Society

- Corporate Social Responsibility Activity

- Ambition Level

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

In academic debates and business environments hundreds of concepts and definitions have been proposed referring to a more humane, more ethical, more transparent way of doing business. This point in time is an important if not critical moment in the development process of new generation business frameworks facilitating sustainable growth. A continuation of the creativity period – “let 100 flowers blossom” – will lead to unclear situations: by the time real progress is at hand a clear and unbiased definition and concept will be needed to lay a strong foundation for the following steps in the development process of corporate sustainability and especially in its implementation.

In the section “Aspects of Corporate Sustainability and Corporate (Social) Responsibility”, I will start with the contemporary critique on CSR. From there I will investigate historical and philosophical arguments (section “A Philosophical Contribution to CS”) supporting or falsifying the proposal to differentiate the notion of corporate sustainability according to the development stages of the organisations. In the section “A Practical Contribution to Corporate Sustainability”, I will deal with the major trends supporting corporate sustainability and elaborate on the changing relationships between corporations, governments and civil society. In the section “Proposals for Defining CSR and Corporate Sustainability”, I will list some recent proposals on the concept and definitions of CSR and CS and will finally propose a set of differentiated definitions of corporate sustainability, each related to a specific ambition level c.q. development level of organizations.

Aspects of Corporate Sustainability and Corporate (Social) Responsibility

Various Notions

An intensive debate has been taking place among academics, consultants and corporate executives resulting in many definitions of a more humane, more ethical and a more transparent way of doing business. They have created, supported or criticized related concepts such as sustainable development,1 corporate citizenship,2 sustainable entrepreneurship, Triple Bottom Line,3 business ethics,4 and corporate social responsibility.5

The latter term particularly has been thoroughly discussed (Göbbels 2002) resulting in a wide array of concepts, definitions and also lots of critique. It has put business executives in an awkward situation, especially those who are beginning to take up their responsibility towards, society and its stakeholders, leaving them with more questions than answers.

Problems with Current Definitions

According to Göbbels (2002), Votaw and Sethi (1973) considered social responsibility a brilliant term: “it means something, but not always the same thing to everybody”. Too often, CSR is regarded as the panacea which will solve the global poverty gap, social exclusion and environmental degradation. Employers’ associations emphasize the voluntary commitment of CSR. Local governments and some Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) believe public–private partnerships can, for instance rejuvenate neighbourhoods. Also various management disciplines have recognised that CSR fit their purposes, such as quality management, marketing, communication, finance, HRM, and reporting. Each of them present views on CSR that align with their specific situation and challenges. The current concepts and definitions are therefore often biased towards specific interests.

Banerjee (2001, p. 42) states that corporate social responsibility is “too broad in its scope to be relevant to organizations” and Henderson (2001, pp. 21–22) “there is no solid and well-developed consensus which provides a basis for action”. The lack of an “all-embracing definition of CSR” (WBCSD 2000, p. 3) and subsequent diversity and overlap in terminology, definitions and conceptual models hampers academic debate and ongoing research (Göbbels 2002, p. 5).

On the other hand, an “all-embracing” notion of CSR has to be broadly defined and is therefore too vague to be useful in academic debate or in corporate implementation. A set of differentiated approaches, matching the various ideal type contexts in which companies operate, could be the alternative.

Jacques Schraven, the chairman of VNO-NCW, the Dutch Employers Association, once stated6 that “there is no standard recipe: corporate sustainability is a custom-made process”. Each company should choose – from the many opportunities – which concept and definition is the best option, matching the company’s aims and intentions and aligned with the company’s strategy, as a response to the circumstances in which it operates.

A Historical Perspective

Past eras have shown acts of charity, fairness and stewardship, such as the medieval chivalry and Scholastic view on pricing, the aristocracy’s noblesse oblige, the early twentieth century paternalistic industrialists and the contemporary ways of corporate (and private) sponsoring of arts, sports, neighbourhood developments, etcetera.

In academic literature, various authors7 have referred to a sequence of three approaches, each including and transcending one other, showing past responses to the question to whom an organization has a responsibility.

According to the shareholder approach, regarded by Quazi and O’Brien (2000) as the classical view on CSR, “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits” (Friedman 1962). The shareholder, in pursuit of profit maximization, is the focal point of the company and socially responsible activities don’t belong to the domain of organizations but are a major task of governments. This approach can also be interpreted as business enterprises being concerned with CSR “only to the extent that it contributes to the aim of business, which is the creation of long-term value for the owners of the business” (Foley 2000).

The stakeholder approach indicates that organizations are not only accountable to its shareholders but should also balance a multiplicity of stakeholders interests that can affect or are affected by the achievement of an organization’s objectives (Freeman 1984).

According to the societal approach,8 regarded as the broader view on CSR (and not necessarily the contemporary view), companies are responsible to society as a whole, of which they are an integral part. They operate by public consent (licence to operate) in order to “serve constructively the needs of society – to the satisfaction of society”.9

The philanthropic approaches might be the roots of CS, but the different approaches to corporate responsibility clearly show that CSR is a new and distinct phenomenon. Its societal approach especially appears to be a (strategic) response to changing circumstances and new corporate challenges that had not previously occurred. It requires organizations to fundamentally rethink their position and act in terms of the complex societal context of which they are a part. This is a new perspective.

A Philosophical Contribution to CS

Value Systems

Abraham Maslow (1968/1982) declared the five basic needs of human individuals, implying that individuals would strive for the next need as soon as the former had been fulfilled. His contemporary Clare Graves concluded that there are many ways of achieving these needs. Individual persons, as well as companies and societies, undergo a natural sequence of orientations [Survival, Security, Energy & Power, Order, Success, Community, Synergy and Holistic Life System]. These orientations brighten or dim as life conditions (consisting of historical Times, geographical Place, existential Problems and societal Circumstances) change. The orientations impact their worldview, their value system, belief structure, organizing principles and mode of adjustment (Beck and Cowan 1996).

If, for instance, societal circumstances change, inviting corporations to respond and consequently reconsider their role within society, it implies that corporations have to re-align all their business institutions (such as mission, vision, policy deployment, decision-making, reporting, corporate affairs, etcetera) to this new orientation.

Graves, and his successors Beck and Cowan, have made clear that entities will eventually try to meet the challenges their situation – featuring specific life conditions – provide or risk the danger of oblivion or even extinction. The quest to create an adequate response to specific life conditions results in a wide variety of survival strategies, each founded on a specific set of values and related institutions. These value systems reflect their specific vision on reality (worldview), their awareness, understanding, and their definition of truth.10 This is why in Seattle, Genoa, Prague representatives of the Global Civil Society clashed with politicians and industrialists; their value systems do not align, there are conflicting truths and worldviews and opposite strategies as to how to deal with (their interpretation of) the situation.

The Principles Behind Evolutionary Development

Ken Wilber (1995), having studied evolutionary developments in great depth, supports Graves when stating: “Evolution proceeds irreversibly in the direction of increasing differentiation/integration, increasing organization and increasing complexity”.11 This “growth occurs in stages, and stages are ranked in both a logical and chronological order. The more holistic patterns appear later in development because they have to wait the emergence of the parts that they will then integrate or unify”.12 This ranking refers to normal hierarchies (or holarchies) converting “heaps into wholes, disjointed fragments into networks of mutual interconnection”.13

As the natural orientations emerged, they clearly show an increase of integratedness and complexity, each stage including and transcending the previous ones.

Wilber drafted 20 “patterns of existence” or “tendencies of evolution” which I shall briefly summarize: reality is not composed of things or processes; it is not composed of wholes nor does it have any parts. Rather it is composed of whole/parts, or holons.14 This is true of the physical sphere (atoms), as well as of the biological (cells) and psychological (concepts and ideas) sphere, or simply said, apply to matter, body, mind and spirit. Atoms or processes are first and foremost holons, long before any “particular characteristics” are singled out by us.

Holons display four fundamental capacities: self-preservation, self-adaptation, self-transcendence and self-dissolution. Its agency – its self-asserting, self-preserving tendencies – expresses its wholeness, its relative autonomy; whereas its communion – its participatory, bonding, joining tendencies – expresses its partness, its relationship to something larger. Both capacities are crucial: any slight imbalance will either destroy the holon or make it turn into a pathological agency (alienation and repression) or a pathological communion (fusion and dissociation). Self-transcendence (or self-transformation) is the system’s capacity to reach beyond the given, pushing evolution further, creating new forms of agency and communion. Holons can also break down and do so along the same vertical sequence in which they were built up.

These four capacities or “forces” are in constant tension: the more intensely a holon preserves its own individuality, preserves it wholeness, the less it serves its communions or its partners in larger and wider wholes and vice versa. This tension can be manifested, for instance in the conflict between rights (agency) and responsibilities (communions), individuality and membership and autonomy and heteronomy.

If holons stop functioning, all the higher holons in the sequence are also destroyed, because those higher wholes depend upon the lower as constituent parts.

In the same way organizations and employees are mutually dependent, as a strike clearly shows. Naturally, organizations support their employees (vertical relationship), creating value as an (horizontal) agency, in constant exchange with its stakeholders (horizontal communion).

Holons emerge holarchically, in a natural hierarchy, as a series of increasing whole/parts. Holons transcend and include their predecessor(s), forming a hierarchical system. What happens if the system itself goes corrupt, turns into a pathological hierarchy? Given the characteristics of holons and hierarchies, a disruption or pathology in one field can reverberate throughout an entire system.

The negative consequences of globalization are good examples of outcomes of a pathological system. With multinationals over-emphasizing their self-preservation (agency), and thus ignoring their participatory role within the community at large, the “threefold global crisis of deepening poverty,15 social disintegration, and environmental degradation” (Korten 2001, p. 13) gave rise to major critique on the business environment.16 It inspired a few individual entrepreneurs to immediately transform their businesses. The majority, however, try to ignore it and continue to disregard their responsibility for its impact on the physical and social environment.

As can be expected from theoretical exercises, countervailing power is emerging in the growth, both in number and impact, of the (global) civil society Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) especially, are building up impact, influencing business and politics towards acting more responsibly and operating in a more sustainable way In the next chapter I will return to the relationship between Business, Civil Society and Government.

Lessons to Be Learned

In addition to the previously mentioned principles of charity and stewardship, often regarded as the roots of CSR, I would like to define two other principles, based on the “natural tendencies of evolution” (Wilber 1995). These are the Principle of Self-determination (or agency, self-preservation) and the Principle of Communion. In combination, the two principles allow each entity, individual or group to act according to its awareness,17 capabilities and best understanding of its situation, provided it does not conflict with current regulations or interfere with the freedom of others to act in obtaining a similar objective. “Freedom stops when it interferes with the freedom of others” (Levinas 1940–1945).

The right to be, the right to define its role within a given situation – the manifestation of agency or autonomy – is balanced by the moral obligation to be accountable for its impact on the environment. It is communion that stops freedom when it interferes with the freedom of others. Being an entity within something larger, obliges to adapt to the environment, adjust itself to changing circumstances and be accountable for one’s impact on others. These principles apply to water molecules as well as human beings and their organizations.

When the chosen role and corresponding awareness appear not to be adequate responses to current circumstances, the system, other related entities in this situation, will influence the subject and try to correct and, as an ultimate response, bring the existence of the subject into jeopardy An increasing number of experiences can demonstrate this principle.

So far we have seen that evolution provides a sense of direction, inspiring both in individuals and corporations goals for transformation.18 Challenged by changing circumstances and provoked by new opportunities, individuals, organizations and societies develop adequate solutions that might be new sublimations, creating synergy and adding value at a higher level of complexity. Since instability increases at higher complexity levels, entities can shift to lower levels should circumstances turn unfavourable or should competences fail to meet the required specifications.

A Practical Contribution to Corporate Sustainability

Why will companies adopt CS practices? Simply stated: they either feel obliged to do it; are made to do it or they want to do it. In this chapter we briefly investigate trends within companies and within society that support the development of CS.

Corporate Challenges

Many companies have mastered their business operations and at the same time created “separate kingdoms”.19 This manifests for instance in employees being more loyal to the business unit than the company, business metrics supporting unit management even at the expense of the performance of the mother company, transfer pricing and information asymmetry between HQ and its divisions. Another contemporary corporate challenge is managing issues in the supply chain. This is even more complex.

In quality management terms these phenomena relate to making shifts or progress in the sequence of quality orientations. Quality management can be oriented at a product level, at process level, at the organization as a systemic entity, at the supply chain and at the society as a whole. Each level includes and transcends the previous ones and each orientation represents a higher level of complexity.

The former ones – product and process quality – can be managed with rather technical and statistical instruments. Creating an organization that functions as a whole instead of separate departments or with managing issues in the supply chain, management needs a shift of approach: the employees and their suppliers have become more important. For instance, to be successful, management has to develop a climate of trust, respect and dedication and allow others to have their fair share of mutual activities (together win). We can conclude that organizations which continue to improve their quality, ultimately have to adopt a more social management style, in other words, move towards (higher levels of) corporate sustainability.

Changing Concepts of Business, Governments and Civil Society

System theorists recommend, as “a cure to any diseased system, rooting out any holon that have usurped their position in the overall system by abusing their power . . .”20 and ignoring their duties and responsibilities, I would add. To root out cancer cells, medics developed surgical techniques and chemical cocktails. By fully abandoning business we would remove ourselves from the creation of wealth and necessary supplies, making the cure much worse than the disease. Mankind needs more subtle approaches to, for instance, increase the individual and collective level of awareness and understanding, support favourable behaviour and restore the imbalance of global institutions.21

Business forms an important triangular relationship with the State and the Civil Society. Each has a specific mechanism that coordinates their behaviour and fulfils a role within society Generally, the State is responsible for creating and maintaining legislation (control), Business creates wealth through competition and cooperation (market), and Civil Society structures and shapes society via collective action and participation.

Both market and control mechanisms have shown major fallacies with respect to organizing societal behaviour. Since civil society has gained importance, both business and government have to respond to the collective actions of civilians, churches and especially NGOs. Corrective actions such as jeopardizing companies’ reputations, challenge companies to apply more sustainable approaches in their business (Zwart 2002).

Once, there were circumstances which resulted in clear-cut roles and responsibilities for both companies and governments, both relatively independent, and an impact on civil society that could be neglected. As complexity grew business and government became mutually dependent entities. Since their coordinating mechanisms were incapable of adequately arranging various contemporary societal topics, the importance of civil society increased. Various representatives stressed “new” values and approaches which politics and business no longer could ignore.

Business has to learn how to operate within interfering coordination mechanisms, with blurred boundaries and surrounding layers of varying degrees of responsibility, overlapping one other. Nowadays, governments increasingly leave societal issues within the authority of corporations. For instance, Schiphol Airport is supposed to limit noise and pollution, and at the same time accommodate the increasing demand for flights. NGOs and other stakeholders expect participation and involvement and request new levels of transparency.

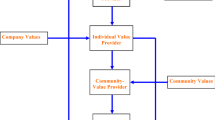

According to various sources in academic literature (e.g. Wartick and Wood 1999) common values and norms play a major role in shaping society. Once it was the government elite that stated the societal values, later business leaders added theirs. Along with the process of democratization, representatives of the civil society have increasingly been introducing “common” values and norms and acting upon them to make government and business respond to these values. We see moving panels, changing circumstances and new existential problems arousing various members in society to act and transform into value systems and corresponding institutional arrangements (Fig. 32.1).

Accepting their new position in society, companies develop new values, new strategies and policies and new institutional arrangements that support their functioning in areas that were once left to others, redefining their roles and relationships with others.

Proposals for Defining CSR and Corporate Sustainability

I will introduce three proposals to define CSR and Corporate Sustainability. I will also deal with the relationship between the two notions.

Corporate Societal Accountability (CSA)

The first one is suggested by Math. Göbbels (2002). He concludes that the inconsistency and sometimes ambiguity of CSR is also due to language problems. Andriof and McIntosh’s (2001, p. 15) introduced the term “corporate societal responsibility” in order “to avoid the limited interpretation of the term ‘social responsibility’, when translated into Continental European cultures and languages, as applying to social welfare issues only. The term ‘societal responsibility’ covers all dimensions of a company’s impact on, relationships with and responsibilities to society as a whole”.

He continued investigating the linguistic approach and concluded in line with Brooks (1995) and Klatt et al. (1999, pp. 17–33) that the word “responsibility” should be replaced by “accountability”, for it causes similar problems as “social”. This would imply a preference to use corporate societal accountability (CSA) as the contemporary term for CSR.

Although I fully agree with its reasoning and suggestion, I expect it will be difficult for policy makers and executives to get used to another new generic notion.

A Hierarchical Relationship Between CSR, CS and Corporate Responsibility

The second proposal was suggested to me by Lassi Linnanen and Virgilio Panapanaan (2002) from Helsinki University of Technology. They consider Corporate Sustainability (CS) as the ultimate goal; meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED 1987). In spite of the traditional bias of CS towards environmental policies, the various contributions at the Corporate Sustainability Conference 2002 at the Erasmus University Rotterdam in June clearly showed sufficient interest in integrating social and societal aspects into CS. The Erasmus University’s Business Society Management has also placed CS as the ultimate goal, with CSR as an intermediate stage where companies try to balance the Triple Bottom Line (Wempe and Kaptein 2002) (see Fig. 32.2). Moreover, the theme of the EU Communication was CSR: a business contribution to Sustainable Development.

The Finnish proposal implies a distinct disaggregation of dimensions – distinguishing sustainability from responsibility (CR) – to draw a more consistent picture. The three aspects of sustainability (economic, environmental, and social) can be translated into a CR approach that companies have to be concerned with. The simple illustration below (Fig. 32.3) depicts the relationship of CS, CR and CSR, plus, the economic and environmental dimensions. This is also to show how CSR as a new tool fits into the current CR or CS framework to complete the picture of corporate sustainability.

Although I fully agree with this new domain of CSR and consequently smaller interpretation of the social dimension of the organization, I doubt if the clock can be reversed.

CSR and CS as Two Sides of a Coin

Keijzers (2002) have indicated that the notions of CSR and CS have shown separate paths, which recently have grown into convergence. In the past sustainability related to the environment only and CSR referred to social aspects, such as human rights. Nowadays many consider CS and CSR as synonyms. I would recommend to keep a small but essential distinction: Associate CSR with the communion aspect of people and organisations and CS with the agency principle. Therefore CSR relates to phenomena such as transparency, stakeholder dialogue and sustainability reporting, while CS focuses on value creation, environmental management, environmental friendly production systems, human capital management and so forth.

In general, corporate sustainability and, CSR refer to company activities – voluntary by definition – demonstrating the inclusion of social and environmental concerns in business operations and in interactions with stakeholders. This is the broad – some would say “vague” – definition of corporate sustainability and CSR.

I will now differentiate this definition into five interpretations, c.q. ambition levels of corporate sustainability. Each definition relates to a specific context, as defined in Spiral Dynamics. Also the motives for choosing a particular ambition is provided for [read CS as CS/CSR]:

-

1.

Compliance-driven CS (Blue): CS at this level consists of providing welfare to society, within the limits of regulations from the rightful authorities. In addition, organizations might respond to charity and stewardship considerations. The motivation for CS is that CS is perceived as a duty and obligation, or correct behaviour.

-

2.

Profit-driven CS (Orange): CS at this level consists of the integration of social, ethical and ecological aspects into business operations and decision-making, provided it contributes to the financial bottom line. The motivation for CS is a business case: CS is promoted if profitable, for example because of an improved reputation in various markets (customers/employees/shareholders).

-

3.

Caring CS (Green): CS consists of balancing economic, social and ecological concerns, which are all three important in themselves. CS initiatives go beyond legal compliance and beyond profit considerations. The motivation for CS is that human potential, social responsibility and care for the planet are as such important.

-

4.

Synergistic CS (Yellow): CS consists of a search for well-balanced, functional solutions creating value in the economic, social and ecological realms of corporate performance, in a synergistic, win-together approach with all relevant stakeholders. The motivation for CS is that sustainability is important in itself, especially because it is recognised as being the inevitable direction progress takes.

-

5.

Holistic CS (Turquoise): CS is fully integrated and embedded in every aspect of the organization, aimed at contributing to the quality and continuation of life of every being and entity, now and in the future. The motivation for CS is that sustainability is the only alternative since all beings and phenomena are mutually interdependent. Each person or organization therefore has a universal responsibility towards all other beings.

The above defined principle of self-determination allows each and everyone to respond to outside challenges in accordance to its own awareness and abilities. Any organization has the right to choose a position from 1 to 5. However not all these positions are equally adequate responses to perceived challenges offered in the environment. The principle of self-determination is balanced by the principle of communion: entities are part of a larger whole and thus ought to adapt itself to changes in its environment and respond to corrective actions from its stakeholders.

The right to be and the capacity to create added value equals the duty to be responsible for its impact and to adjust itself to changes in its environment. Without conforming to this principle, organizations ultimately risk extinction.

A differentiated set of CS/CSR definitions implies that there is no such thing as the features of corporate sustainability or CSR. Each level practically manifests specific CS and CSR activities, manifesting the corresponding intrinsic motivations. In other words, the various CSR and CS activities can be structured into coherent institutional frameworks supporting a specific ambition of CS/CSR. Some levels include a wide range of advanced developments within CS and CSR, while others, the more traditionally oriented, have almost none.

The coherent institutional frameworks supporting specific levels of CS/CSR, can be difficult thresholds preventing companies from adopting higher levels of corporate sustainability. This might explain why, according to worldwide research by Ernst & Young22 among 114 companies from the Global 1,000, 73% confirmed that corporate sustainability is on the board’s agenda; 94% responded that a CS strategy might result in a better financial performance, but only 11% is actually implementing it.

In Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability, Marcel van Marrewijk and Marco Werre (2003) show that specific interventions can only be adequately addressed within a specific context and situation. A higher ambition level and specific CS interventions require a supporting institutional framework and value system. The authors developed a matrix distinguishing six types of organizations at different developmental stages, their corresponding institutional frameworks, demonstrating different performance levels of corporate sustainability.

Abbreviations

- CS:

-

Corporate sustainability

- CSR:

-

Corporate Social Responsibility

- ECSF:

-

European Corporate Sustainability Framework

- SRI:

-

Socially Responsible Investing

- VNO-NCW:

-

Dutch Employers Association

- WBCSD:

-

World Business Council for Sustainable Development

References

Andriof, J., and M. McIntosh, (eds.) 2001. Perspectives on corporate citizenship. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Banerjee, S.B. 2001. Corporate citizenship and indigenous stakeholders. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, Issue 1: 39–55.

Beck, D., and C. Cowan. 1996. Spiral dynamics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Brooks, T. 1995. Accountability: It all depends on what you mean. Clifton: Akkad Press.

Committee for Economic Development. 1971. Social responsibilities of business corporations. 16 New York: CED.

Drucker, P. 1984. The new meaning of corporate social responsibility. California Management Review 16(2): 53–63.

Elkington, J. 1997. Cannibals with forks. The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Oxford: Capstone Publishing Ltd.

Foley, J.A., S. Levis, M.H. Costa, et al. 2000. Incorporating dynamic vegetation cover within global climate models. Ecological Applications 10: 1620–1632.

Foucault, M. 1970. The order of things. New York: Random House.

Freeman, R.E. 1984. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Marshfield: Pitman Publishing Inc.

Friedman, M. 1962. Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Göbbels, M. 2002. Reframing corporate social responsibility: The contemporary conception of a fuzzy notion.

Hawken, P. 1993. The ecology of commerce: A declaration of sustainability. New York: Harper Business.

Henderson, D. 2001. Misguided virtue. False notions of corporate social responsibility. Wellington: New Zealand Business RoundTable.

Keijzers, G., R. van Daal, and F. Boons. 2002. Duurzaam Ondernemen, strategie van bedrijven. Deventer: Kluwer.

Kilcullen, M., and J. Ohles Kooistra. 1999. At least do no harm: Sources on the changing role of business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Reference Services Review 27(2): 158–178.

Klatt, B., S. Murphy, and D. Irvine. 1999. Accountability: Practical tools for focusing on clarity, commitment and results. London: Kogan Page.

Korten, D. 2001. When corporations rule the world, 2nd ed. San Fransisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Levinas, E. 1961. Totality and infinity. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Linnanen, L., and V. Panapanaan. 2002. Roadmapping CSR in Finnish companies. Helsinki: Helsinki University of Technology.

Marsden, C., and J. Androf. 1998. Towards an understanding of corporate citizenship and how to influence it. Citizenship Studies 2(2): 329–352.

Maslow, A. 1968/1982. Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Marrewijk, M., and T.W. Hardjono. 2001. The social dimensions of business excellence. Corporate Environmental Strategy 8(3): 223.

Marrewijk, M., and M. Werre. May 2003. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics 44(2 and 3): 107–119.

McGuire, J.W. 1963. Business and society. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pirsig, R. 1991. Lila, an inquiry into morals. New York: Bantam Books.

Quazi, A.M., and D. O’Brien. 2000. An empirical test of a cross-national model of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 25(1): 33–51.

Steiner, G.A., and F.S. Steiner. 2000. Business, government and society. A managerial perspective. New York: McGraw-Hill.

van Marrewijk, M. 2003. European corporate sustainability framework. International Journal of Business Performance Measurement 5(2/3): 121–132.

van Marrewijk, M., and T.W. Hardjono. May 2003. European corporate sustainability framework for managing complexity and corporate change. Journal of Business Ethics 44(2–3): 121–132.

Votaw, D., and S.P. Sethi. 1973. The corporate dilemma: Traditional values versus contemporary problems. New York: Prentice Hall.

Wartick, S.L., and D.J. Wood. 1998. International business and society. Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

WCED – World Commission on Environment and Development or the Brundtland Commission 1987.

Wempe, J., and M. Kaptein. 2002. The balanced company. A theory of corporate integrity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilber, K. 1995. Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Boston: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. 2000. A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science and spirituality. Boston: Shambhala.

World Business Council for Sustainable Development WBCSD. 2000. Corporate social responsibility: Making good business sense. Geneva: WBCSD.

Zadek, S. 2001. The civil corporation. London: Earthscan Publications.

Zwart, A. van der. 2002. Reputatiemechanisme in beweging: doelstreffend bij issues aan MVO? Master thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam.

Acknowledgements

While writing the basic draft of this article in the beautiful valley of the Ardech, France, I made particular use of an overview article on CSR by Math. Göbbels [see Chaps. 2, 5] and the work of Ken Wilber [see Chap. 3].

Furthermore, I wish to acknowledge the constructive and useful comments of earlier versions of this article by Teun Hardjono, Marco Werre and my wife, Erna Kraak.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

van Marrewijk, M. (2013). Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. In: Michalos, A., Poff, D. (eds) Citation Classics from the Journal of Business Ethics. Advances in Business Ethics Research, vol 2. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4126-3_32

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4126-3_32

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-4125-6

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-4126-3

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)