Abstract

This contribution is related to the quality of life in developed nations. Developed nations are not a strictly defined category, and in this article we regard as developed the nations of Europe, of North America, Australia, and Japan, where the last one is the only country which is not a European offshoot. Development in its original sense was mainly defined as economic growth in the course of industrialization. The comprehensive developmental process of the present world is usually defined as globalization. It is mainly understood as a worldwide process of increasing interdependency of people, goods, capital, and information. Among the societal goals in this development phase, quality of life attained a significant position. Beginning in the 1960s in the developed worlds, quality of life got more and more recognition as a societal goal. Quality of life is understood as objective conditions, investigated through social and technical experts, as well as subjective perceptions through the people. In consequence of defining new societal goals, the idea to measure these goals arose and measurement procedures were established worldwide. The comparative aims of this article are as follows: First, the main features of the scientific discussion on the concepts of quality of life and social well-being are explored. In scientific discussions, quality of life is partly emphasized more in objective terms and partly more emphasis is given to the subjective dimension of quality of life. Second, the objective dimension of quality of life is outlined with comprehensive indicators from the Human Development Index (HDI), the Human Well-Being Index (HWI), and the Weighted Index for Social Progress (WISP). It is shown how far they lead to similar results and to differences. Third, the subjective dimension of quality of life is described with regard to the perceived quality of life in terms of overall satisfaction with life (OSL), of positive and negative affect (ABS), and of personal and national well-being (PWI/NWI). Above that, there are approaches which combine objective and subjective aspects of life in a comprehensive index (e.g., the Happy Life Expectancy). In total, it is no surprise that the choice of criteria and values influences to a high degree the results of the state of nations. The question from the perspective of globalization is whether there are tendencies toward more similarity or to more divergence between the nations and continents.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Life Satisfaction

- Gross Domestic Product

- Human Development Index

- Ecological Footprint

- Subjective Dimension

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Development, Globalization, and the Quality of Life

More than 2,000 years ago, it seemed as if the main regions on earth were rather equal in respect to their economic power, but then, a development process took place characterized by growth, differentiation, and inequality. The economic growth was not continuous. There was a slow growth in the first millennium and a rapid growth after 1820 when industrialization came into power (Maddison 2001). The growth tendency was accompanied by an increasing disparity between richer and poorer regions. The world map of the distribution of wealth (measured by GDP per capita) shows that Europe was leading and “the Western offshoots” which are constituted by the USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, belonged also to the most wealthy world regions (Maddison 2001, p. 264). In terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), they were part of the highly developed areas of the world, and only a few additional countries of the world like Japan attained similar economic success.

Many nations joined and are still joining the path of industrialization and economic growth. This has been accompanied by a challenging discussion about the reasons for different developmental paths in terms of performance and exploitation.

The ongoing, long-term process of the developed world is often defined as modernization, and in its latest stage, it is characterized as globalization. This is a worldwide process of increasing interdependency of people, goods, capital, and information. New features of the modern world in recent decades result from the enforcement of international networks in economic, social, and cultural terms. The arguments that globalization influences quality of life are often to be found in the sense that “globalization brings good and bad news” (Henderson 2002). As described sometimes, a “global village” seems to emerge, but it is also shown that developments are running in different directions; inconsistencies and ambivalences are characterizing the world of the twenty-first century (Camfield 2004).

Aside from the highly developed countries, we find many less-developed countries especially in Africa and South America and also a number of better-off countries; for example, the tiger countries in Southeast Asia. Due to the availability of scarce resources like oil, there are also newcomers among the wealthy countries. Nevertheless, this chapter is concentrated on countries with the experience of a long-term industrialization and modernization.

Beginning in the 1960s of the last century, the question of quality of life arose due to continuing economic success. The social costs of economic growth got more and more into public awareness, especially the environmental damages and the loss of future resources. Also, the doubts grew that increasing GDP at a high level could not contribute to increasing quality of life. Already in the last century, conventions about national accounts were developed worldwide for measuring economic activities and wealth, but this was not the same for measuring quality of life. Nevertheless, a number of different concepts for defining and measuring quality of life in objective as well as in subjective terms are now available (Nussbaum and Sen 1993; Offer 1996; Rapley 2003).

One question is the same for modernization and globalization as it is for quality of life: Is there one pattern or are there some competing models or perhaps a multi-variety? The discussion of this issue will be kept to the end of this chapter. First, there is the issue of definitions.

Definitions of Quality of Life in the Developed World

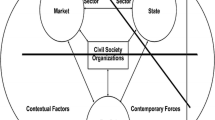

While the term quality of life was already mentioned in the 1920s (by Cecil Pigou), the character of this as a societal goal was attained later in the 1970s (Glatzer et al. 2004). The process of discussing and defining quality of life began in the USA earlier than in Europe. There was one very significant difference: in the USA, a strong preference for the subjective approach to quality of life gained acceptance whereas in Europe—at least in Scandinavia and to a certain degree in Central Europe—more emphasis was given on objective indicators which measure social conditions independent from individual awareness. In both areas, more and more concepts (and also indicators) were developed, which are roughly shown in the scheme below.

As shown in Overview 18.1, quality of life and social well-being are basically defined as a constellation of components which can consist of objective living conditions and/or of subjectively perceived well-being. Experts from the social and natural sciences usually monitor the objective living conditions, which exist to a certain degree independently from the awareness of the population exposed to them. Their range may vary from the personal context through the community domain to the world’s environmental conditions. Some approaches prefer to focus on social problems, preferably on poverty, social exclusion, and social inequality.

Subjectively perceived well-being consists of evaluations made by individuals; subjective quality of life is here in the eye of the beholder. Investigations of the subjective perceptions of well-being have demonstrated that it is a multifaceted concept. It has a positive side, which is mostly described in terms of satisfaction, happiness, and others. Its negative side is defined in terms of worries, anxieties, and further aspects. For the subjectively perceived part of reality, there are comprehensive concepts like satisfaction with life as a whole and happiness in general; these concepts can be deconstructed down to many life domains.

The relationship between objective conditions and subjective perceptions is usually not very strong, and there are typical constellations of good and bad levels. For example, the type of quality of life called well-being is described as good conditions and good feelings whereas deprivation is characterized by low levels of living conditions and bad feelings of the people exposed to them. Dissonance—good conditions with bad feelings—and adaptation—bad conditions with good feelings—are the inconsistent types (Zapf 1987, p. 17).

Several investigations have shown that negative well-being is only modestly correlated with positive well-being. This means some people are satisfied and happy though they have a high burden of worries, while others are unhappy though they have only few worries. In consequence, subjective well-being is a somewhat complicated and ambivalent concept.

In addition to positive and negative dimensions of well-being, another dimension has to be regarded: future expectations: It is a very different experience if somebody in a bad situation looks optimistic into the future compared with them seeing no way out. This is the reason why future expectations should also be emphasized as a component of quality of life. Optimism and pessimism become an essential part of the concept of quality of life.

Objective Measurement of Quality of Life

In the tradition of objective measurement, there are a few approaches which are designed and implemented in a worldwide perspective. Comprehensive indices have been developed and counted for most countries (Sharpe 1999; Noll 2004). The most interesting indicators are the Human Development Index (HDI), Human Well-being Index (HWI), and the Weighted Index of Social Progress (WISP). Beside these well-documented well-being indicators, there are additional ones presented in newspapers, in journals, and on Internet pages often with a scientific origin. The three indicators named above play a significant role in scientific discussion, and they are statistically available for all the developed countries are included in this chapter. Often, the main indicators are not seen as sufficient, and therefore a number of satellite indicators are added in order to give a more detailed picture of the conditions in societies.

Human Development: The Human Development Index (HDI)

The concept of human development was derived by the United Nations. It is embedded in a broader goal discussion about millennium development goals, human development, and human rights (Human Development Report 2005). Certain components, which are related to the concept of quality of life, are defined as key capabilities for human development. They concern preferably three goal areas which are:

-

To lead a long and healthy life

-

To acquire knowledge

-

To have access to resources needed for a decent standard of living

Thus, only three components—length of life, knowledge enlargement, and standard of living—are the main criteria for quality of life. Additionally in the concept, but not considered essential conditions for human development, are environmental sustainability, the protection of personal security, and political rights as well as equity and gender equity.

According to the HDI, the three goal areas are operationalized in the following way:

-

A long and healthy life as measured by life expectancy at birth

-

Knowledge as measured by the adult literacy rate (with two-thirds weight) and the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio (with one-third weight)

-

A decent standard of living as measured by GDP per capitaFootnote 1

The HDI indicator is available for many countries. Its range varies from 0.968 for the best countries (Iceland and Norway) to 0.336 for the weakest country (Sierra Leone) (Human Development Report 2007/2008, p. 229–232). In the concept of the United Nations, the value of 0.800 marks the border between “high human development” and “medium human development.” Among the countries classified as highly developed, we find 70 countries, among them are all European countries and the other highly industrialized countries (see Overview 18.2).

According to the HDI of 2005, Norway and Iceland are the most highly developed countries in the world followed by two non-European countries—Australia and Canada. Ireland, Sweden, and Switzerland closely follow. A little bit lagging behind are Japan, then the USA, and New Zealand. It is remarkable that they score higher than the bigger European countries like Germany and Great Britain. Within the European countries, there is a downward shift from the northern through the central and southern to the eastern countries.

With such well-documented data, it is possible to show for each country what the different indicators contribute to the overall indicator. For example, the good position of the USA in relation to Germany and the UK is due to their high GDP index and not so much to their life expectancy index and their education index. Thus, the superior position of the USA is mainly a consequence of its economic success.

As the time series of the HDI go back to the year 1975, it is possible to demonstrate how the leading position of the USA at the beginning of these international comparisons has changed. Indeed, in 1975, only one European country—namely Denmark—showed a slightly higher HDI than the USA. Between 1975 and 1990, only few changes in the relative positions of the European countries and the USA occurred, but from 1995 onward, more and more European countries claimed a level equivalent to that of the USA, and today, there are eight European countries above the level of the USA. Additionally, Australia and Canada have also surpassed the USA. Thus, the USA lost its leading position to several European and non-European nations in the past two decades.

Additional Comparisons: The human development concept goes far beyond the HDI. Quality of life indicators in the core sense are enlarged through indicators of negative well-being and social problems. In consequence within the HDI approach, significant satellite indicators are related to human poverty, unemployment, the impact of HIV/Aids on health, and to victimization, but also female economic activity and the mechanization of everyday life are included into the presentation.

Output indicators from a comprehensive collection of development indicators enlarge the picture given by the HDI. The good position of the USA as measured by the HDI is challenged by the Human Poverty Index for developed countries (declared as HPI-2) which includes the population below the poverty line as well as some additional aspects. This shows that no country in Europe shows a higher Human Poverty Index than the USA. That is, the high economic success of the USA in terms of GDP is accompanied by overproportional poverty in terms of HPI. This can be further demonstrated by the percentage of income that goes to the lowest 10% of a country’s population. Again, there is no country in Europe which gives such a small share to the poor as the USA. Additionally, there is no country in Europe which leaves a higher income share to the top 10% than the USA (it is 30% of total income). But some of the European countries are not very far behind on this measure.

Another important indicator for quality of life and economic performance is the unemployment rate, which is in the European context is related to social exclusion. It is not always defined and counted in fully comparable ways among the countries; this requires expansion.

A further problem of comparability is that yearly results of the unemployment rate sometimes vary by chance. Because of this, it is better to compare the whole decade from 1991 to 2001. On this measure, the average unemployment rate shows the USA to be in a medium position. Most of the smaller European countries have a lower value than the USA, but the bigger countries such as France, Germany, the UK, Spain, and Italy are above. Far above are the newcomers in the European Union like Poland and Slovenia who had much lower unemployment rates in the decades before the dissolution of the Soviet Empire but which are now much higher. Overall it can be said that unemployment is an increasing burden in Europe, more so than in the USA.

The goal of leading a long and healthy life has been challenged by the HIV virus, which remains a continuing danger. The impact on a society is shown by the proportion of people living with HIV/AIDS, as a percentage of adults aged between 15 and 49 (United Nations 2005, p. 258). The figure for the USA (0.61%) is higher than for all European countries in 2001. Only Spain, Italy, and Portugal get near to the USA, whereas Northern Europe and Central Europe show very low figures. Clearly, in terms of HIV/Aids risk, the USA has worse conditions compared to Europe.

Security, which is a high value on both continents, is expected to be different due to the differences in societal conditions and the respective approaches to law and punishment. One outcome measure for security is the percentage of people victimized by crime as a percent of the total population measured in representative surveys. These data refer to people victimized by one or more of the following 11 crimes: robbery, burglary, car theft, car vandalism, bicycle theft, sexual assault, theft from car, theft of personal property, assault, and threats, and theft of motorcycle or moped (United Nations 2005, p. 308/9). The position of the USA in the International Crime Victim Surveys from the years 1995 to 1999 is above some of the European countries, the highest of which are Portugal (15.5%), Switzerland (18.2%), Austria (18.8%), and Finland (19.1%). Many European countries are close to the USA with 21.1%, but some have significantly higher values. The percentage of victims of crime varies substantially across the European countries, such that the USA does not constitute an exceptional case.

The human development approach as a whole is in the tradition of social reporting broad and flexible; its index is rather narrow and a compromise between traditional and rising concerns.

Well-Being Assessment: The Human Well-Being Index (HWI)

The approach called “well-being assessment” is concerned especially with the relationship between people and the ecosystem and how they affect one other (Prescott-Allen 2001). This form of assessment is related to human concerns in five dimensions, as:

-

Health and population are related to the goal of people enjoying long lives in good health while keeping their numbers within the bounds of human and natural resources.

-

Wealth, in terms of private and national wealth, implies that individuals and households have the material goods and income to secure basic needs and decent livelihoods and that the community has the resources to support enterprise and maintain prosperity.

-

Knowledge assures that people have the capacity to innovate and cope with change, live well and sustainably, and fulfill their potential, and culture is concerned with avenues for spiritual growth, creativity, and self-expression.

-

Community means freedom and governance, where human rights are fully respected, and individuals are free to choose which decisions are made and who should make them as well as peace and order. Communities coexist peacefully and protect their members from crime and violence.

-

Household and gender equity assures that benefits and burdens are shared fairly among households, all groups, and between males and females.

The index constructed for these dimensions runs from 0 to 100Footnote 2: In practice, the countries attain values between 3 (Sierra Leone) and 82 (Norway). On the basis of the well-being index, the differences between the nations are described in qualitative terms: “good,” “fair,” “medium,” “poor,” and “bad.” All the developed countries are classified as fair. Worldwide, there are only two “good” countries which belong to the Nordic countries namely Norway and Finland. Denmark also scores 71 in the table below. For a more detailed analysis, it may be useful to show the differences between the USA and Germany, which is the biggest country in the EU, for the domains of human well-being. Germany is better off in respect to “community” and “equity” whereas the USA scores higher on “wealth” and “knowledge.” “Health” is about the same in both countries. These comparisons give hints where all the 180 countries of the world have their advantages and their deficits.

An enlightening view on the differences between Europe and North America is attained when the European countries are separated into the group above and the group below the USA, which rates 73 points on the HWI scale. There is a very clear result in the sense that compared to the HDI, the HWI positions more European countries above the level of the USA. According to the concept of the HWI, all countries of Northern and Western Europe together with Italy and Spain are better-off than the USA. All the Eastern and the remaining Southern European countries are less advanced than the USA.

The perspective of this approach is in the course of the argument broadened into the ecosystem. The well-being method starts with the intention of covering both people and the ecosystem and ascribes equal weight to them. Again, as in the case of the HDI approach, there is an enlargement of dimensions with emphasis on ecosystem well-being, which is in the end combined into a comprehensive index. The flexibility of the approaches for enlarging demands is rather high (Overview 18.3).

Human well-being index (HWI) for developed countries 2000 (Source: Prescott-Allen 2001, p. 150–152)

Social Progress: The Weighted Index of Social Progress (WISP)

Social progress is a very traditional goal, which is used as final objective (Estes 1984, p. 17). The starting idea is to define indicators which are clearly accepted as signs of progress if they move to the better. Altogether there are 40 indicators as measures of progress. An aggregation of the 40 indicators to ten subindices is performed. Many more dimensions are included than in the previous approaches. The WISP is finally computed with weights for the dimensions derived from a factor analysis.

The areas of the subindices are Education, Health Status, Women Status, Defense Effort; Economic Sub-index; Demographic Sub-index; Environmental Sub-index; Social Chaos Sub-index; Cultural Diversity Sub-index; Welfare Effort Sub-index (Overview 18.4).

Weighted index of social progress (WISP) for developed countries 2000 (Source: Estes 2004, p. 132; http://www.sp2.upennn.edu/~restes/WISP2000/Table %2045c 00pdf, 11.10.2011)

The four North European countries are at the top of world social leaders: Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland with index values of 101–107. The middle-performing countries include Estonia, Romania, and others. The lowest value in Europe was attained for Albania (63), one of the socially least development countries. Germany is the reference point with the index value of 100. The order of countries is changing compared with HDI and HWI. Most astonishing is that the USA is now in a rather low position just above some East European countries (Estes 1988, 1997).

Overall, it turns out that the Northern European, followed by Western European countries, are the top ones according to the WISP. The leading position of the northwest of Europe is the result of the influence of a broad variety of societal dimensions. As in respect to HDI and HWI, the highest score for the USA can be found in the economic subindex whereas the lowest score shows up in the poverty burden. While Europe as a whole scores higher than the USA, due to the higher scores of the West and the North, South and the East Europe are below the scores of the USA.

The WISP has been computed between 1970 and 2000. Consequently, there are results in long-term perspective as follows:

The USA and the regions of Europe had improved between 1970 and 1990 according to the WISP, but they have lost indicator points between 1990 and 2000. Thus, two decades of success were followed by one decade of backward movement.

Comparisons Between Objective Comprehensive Indices

Looking at the previous sections, one could argue that it is possible to create statistically rather different results. But despite different indicators, the similarities are also striking. Northern European countries are always at the top of the measures of well-being. However, depending on the type of index used, the USA may be above Europe, on the middle level of Europe or behind Europe. This is no arbitrariness. The point is that we have first to define our values and criteria, and then we can estimate the well-being of our nations. If values and criteria are different, then the outcomes are different. The HDI contains only three criteria and gives a high weight to GDP (one-third); HWI uses around ten criteria, and WISP uses about 40 indicators concerning many soft social domains and giving only marginal weight to conventional GDP. The rather high scores for the USA depend to a high degree on the emphasis on economic indicators.

Subjective Measurement of Quality of Life

The approach of subjective perception of quality of life developed on the basis of survey research and was, in the beginning, mainly elaborated in the USA. But not much time elapsed until most of the Europeans and also the Australians utilized the subjective approach. There are now a large number of indicators for the perceived quality of life. One of the main steps forward in this research field was the central archive, built at Rotterdam, called the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 1984, 2005a, b). This constitutes a systematic collection of subjective indicators and statistics from all over the world. In the following account, three types of indicators are illustrated as the Overall Satisfaction with Life (OSL) as a one-item indicator, the Affect Balance Scale (ABS) as an indicator which contains positive and negative dimensions of affect, and the Personal Well-being Index (PWI) as a multidomain indicator.

Satisfaction and Happiness: Overall Satisfaction with Life (OSL)

Both satisfaction with life and happiness are often conceived as a concept in the sense of a subjective overall evaluation of life. They are regarded as the most simple and efficient measures of how a population perceives its quality of life. It is an astonishing performance of our brain to express satisfaction for all the aspects of life in one evaluation. No other term than satisfaction could be used for evaluating the mood at a dinner, the beauty of one’s spouse, the attractiveness of a region, and the tensions in the world system. Of course, satisfaction is a subjective expression, and it is not always absolutely sure that people give the “true” answer. The answer to the question “how satisfied are you, all in all, with your life” seems, after long scientific experience, the best description that we can get with respect to a personal assessment of life for a large number of people. And the answer scale from 0 to 10 seems to have the most useful capabilities.

Examples for this kind of survey question have been collected in the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2005a, b), and some are available on the Internet for accounting procedures as the World Value Surveys (Halman et al. 2008). These data about life satisfaction allow international comparisons, based on the same scales, investigating the satisfaction hierarchy of countries, regarding the satisfaction distribution in the countries, and showing changes in the past decades. According to these data rather stable pattern have emerged.

The Satisfaction Hierarchy of Developed Countries

It is a privilege of the small countries in Europe to show the highest satisfaction level for their population (compare Delhey 2004). The indicators at the change of the last century show the top satisfaction countries: Switzerland, Denmark, and Malta joined by Ireland, Iceland, and Austria which are followed by the Netherlands and Luxembourg. All these countries have less than ten million inhabitants, and this suggests that small countries are more easily able to develop high satisfaction levels. A big country like the USA or Germany has never attained the satisfaction level of small countries like Denmark, which is often the highest. It must be a specific advantage connected with the size of small countries which produces high satisfaction, among them surely the feelings of identity and of belonging together.

The USA is a nation which shows relatively high satisfaction but below the small European countries and Canada. All the bigger countries of Europe have a lower satisfaction level than the USA: Germany, Great Britain, France, Italy, Spain. Below all the West European and North American countries is the satisfaction level of Japan. Below the Japanese satisfaction level, we find only some East European countries (Overview 18.5).

Overall satisfaction with life (OSL) for developed countries 1999/2000 (Mean Values on Satisfaction Scale: 11-point scale from 0 (dissatisfied) to 10 (fully satisfied) Source: The Value Surveys 1981–2004 (http://www.jdsurvey.net/bdasepjds/QuestionMarginals.jsp 06.06.2008))

The European Union as a whole contains very different satisfaction levels; the range of European countries is broader than the range of the remaining developed countries. This hierarchy among developed countries is rather stable between different surveys.

The Distributions of Satisfaction Scores Within Nations

The question of how satisfaction scores are distributed indicates the potentials of satisfaction and dissatisfaction in society. Among the developed countries, we do not find a low satisfaction level. We know for sure that all developed countries show a negatively skewed distribution with the most numerous values in the positive area. This means that in all these societies, the satisfied fraction overwhelms the dissatisfied fraction. We never find a bipolar distribution or a right skewed distribution which probably would be an indicator of far-reaching political instability and confrontation. The left skewed distribution represents a mixture of satisfaction and dissatisfaction which allows dissatisfaction of some few individuals. Nevertheless, it leads to a rather stable situation in the society. The following table exhibits the distribution of satisfaction scores for three types of countries: Denmark for a rather high satisfaction, the USA for a middle satisfaction, and Japan for a relatively low satisfaction among the developed countries (Overview 18.6).

The distribution of life satisfaction scores measured with a ten-point scale in Denmark, the USA, and Japan 1999/2000 (Source: The Value Surveys 1981–2004 (http://www.jdsurvey.net/bdasepjds/QuestionMarginals.jsp 06.06.2008))

The question of inequality of satisfaction takes us a step further. Satisfaction could be equally or unequally distributed, and it is a core question to find out whether the distributions are developing in the direction of more or less equality. It is a deep philosophical-political question as to whether it is more important that people should feel equal in subjective terms or if people should be equal in objective terms.

Most people in the highly developed world reached about the same satisfaction level from 1981 to 2000 (Overview 18.7). This is especially true for Denmark with the highest level, the USA as the biggest country in the middle of the satisfaction scale, and Japan at the end (see Overview 18.8).

Satisfaction with life in developed nations from 1981 to 2000 (Explanation: Different researchers prefer different representations of the same indicator dimension. Most often, they give the mean for the satisfaction scale from 0 to 10; the table here shows another possibility, the percentage of respondents who score higher than 5. The idea here is to show the satisfied share of the population. Source: World Value Surveys 1981–2004, Online)

The stability of satisfaction in the societal average does not mean that the individuals are stable in respect to their quality of life. Many individuals may change while the whole society remains stable. If the same number of individuals increase their satisfaction as reduce their satisfaction, this could sum up to no change of the societal satisfaction level.

Historical Comparisons of Perceived Quality of Life

The content of quality of life was some time ago not a developed concept, even though questions in relation to perceived quality of life already emerged more than 50 years ago (see Overview 18.9). One set of internationally comparable data goes back to 1975, with data from Gallup surveys. Quality of life was examined by using an 11-point response scale (see Overview 18.8). Researcher discovered a higher satisfaction with life in the USA than in the European Union.

Even earlier, in 1948, a three-step way of life satisfaction scale was used, which is today unusual. The question was related to the “satisfaction about the way of getting on.” Satisfaction is much higher in the USA compared with Western Europe. This is reasonable in the light of postwar conditions, which were much more destructive for Europe than for the USA.

Affect: The Affect Balance Scale (ABS)

Another type of multidimensional construct for measuring quality of life in international terms is the Affect Balance Scale, which was used in the context of early, more psychological investigations of quality of life (Bradburn 1969). As with the Personal Well-Being Index, the Affect Balance Scale is multidimensional but in a different way; it is not only related to positive life dimensions but also includes negative affect in the recent past experience of individuals. It is a ten-item rating scale including five statements reflecting positive feelings and five statements reflecting negative feelings. The items are related to a high degree to positive and negative events in everyday life, which happen usually to everybody. The answers to the questions are offered in a yes or no format. Respondents are asked to focus on feelings that they have experienced during the past few weeks.

The questions reflecting positive feelings are:

-

Pleased about having accomplished something?

-

That things were going your way?

-

Proud because someone complimented you on something you had done?

-

Particular excited or interested in something?

-

On top of the world?

The questions reflecting negative feelings are:

-

So restless that you could not sit long in a chair?

-

Bored?

-

Depressed or very unhappy?

-

Very lonely or remote from other people?

-

Upset because someone criticized you?

Source: Bradburn 1969, p. 3 ff

The list of items makes clear that the concern is more on psychological rewards, which most people experience in everyday life. The concept is related to “process benefits” (Juster) and is not taking account of the evaluation of living conditions. The average score on the scale between −5 and +5 on the Affect Balance Scale at the top is 2.9 for Sweden and at the bottom is 0.39 for Japan.Footnote 3 It is only partially the same order as overall satisfaction with life. If the index is regarded with respect to its separate positive and negative parts, it is evident that in the USA, people have on average a much higher positive affect, but the negative affect is similar to other countries. The Affect Balance Scale shows that the negative burden of life and the positive side of life vary somewhat independently. The different patterns that Bradburn’s Affect Balance Scale is indicating for the various societies of the world reflect mainly their differences in their cultures of everyday life (Overview 18.10).

Perceived Well-Being: The Personal Well-Being Index (PWI)

In the debate about quality of life, there are always voices saying that it is not possible to reduce quality of life to one dimension. Indeed, one item alone can never meet the differentiation and intricacy of subjective well-being. Moreover, a certain number of items would lead to a more informative representation of subjective well-being. One of the most interesting approaches in the line of a deconstruction of life satisfaction is the differentiation between personal and national well-being as shown in the items of Overview 18.11. The Personal Well-Being Index (PWI) contains eight items, and its complement, the National Well-Being Index (NWI), consists of six items (Cummins et al. 2003; Lau 2005).Footnote 4 According to the underlying idea, a small number of items should be developed that represent a big share of the variance of quality of life. The list of countries included is up to now ad hoc (Cummins et al. 2004).

Personal well-being index and national well-being index 2007 (Percentage: Share of respondents who tell to be satisfied between 7 and 10. Source: Cummins et al. (2007), p. 4)

The answers are counted on an 11-point scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means completely dissatisfied and 10 means completely satisfied. A lot of tests were conducted using this measurement instrument, and they showed adequate construct validation for the well-being scale (Cummins 2004).

The results after some years of research are special for subjective multi-item scales. First, there are the same dimensions which receive a lot of positive resonance in nearly all countries. Second, it is shown that the various indicators behave differently in direction and magnitude. Third, there are different levels between personal well-being and national well-being, which are both measured by a multi-item index. Fourth, in the Australian time series, the influence of major international events is documented. It works sometimes in unexpected directions: For example, the disaster in one country—September 11th in the USA—contributed to higher satisfaction in Australia because people were stimulated to develop more internally cohesion. So national comparisons may be used to detect the influence of world events between nations.

Comparisons of Different Subjective Measures

In the subjective dimension, we find similar results over many years, from a number of surveys and across different scales. The conclusion is that these results are rather good indicators for the perceived quality of life. Various tests for reliability and validity support this view. Obviously, a broader battery of indicators gives a more adequate picture for a whole nation than a single indicator.

With the growing awareness of the subjective dimension, there emerged various needs for subjective data. Two data archives should be mentioned: The World data archive of happiness at Rotterdam collects all the relevant subjective data in a systematic manner. Another enterprise is the World Values Survey. It collects self-produced data, which are related to a certain degree to the perception of quality of life.

The creation of new data for quality of life reveals that the Northern European countries again attain the best indicator values. There seem to exist societal conditions which are close to the needs and values of the people in these countries, and therefore life is perceived of better quality.

New Approaches of Societal Analysis

Whereas the monitoring of societal trends has a longer history, the survey-based investigation of the subjective dimension is a rather new perspective on societies. The investigation of this dimension is accompanied by new approaches for societal analysis. Three such approaches will be described in the following: One novelty concerns indicators which combine objective and subjective dimensions of reality. Another approach is the distribution of subjective data in a society especially in respect to inequality. Finally, the concomitants of subjective well-being including its ecological impact are now on the research agenda.

Combinations of Objective and Subjective Data

The combination of objective and subjective data into one index happens seldom. The reason is presumably that it is necessary to bring together data from different sources and in each case one has to find a common denominator. One example for such an approach is the Happy Life Expectancy (HLE), which was developed by Ruut Veenhoven (1996). Until recently, the data are available for 91 countries. This index combines, on the objective side, the average length of life in years with, on the subjective side, the average appreciation of life on a scale from 0 to 1. The result of a multiplication of these two parameters is the HLE index, designed to indicate happy life years (Overview 18.12).

Happy life expectancy (HLE) for developed countries 1995–2005 (Source: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_nat/findingreports/RankReport2006)

In this approach, the highest available value is attained for Switzerland with 63.9 years of happy life expectancy, and the lowest value is found in Bulgaria with 30.0 years. Above 60 years counts as “top,” below 25 years is defined as “bottom,” and in between as middle range. According to the results of the previous indicators, most of the top countries are again in North European (Denmark, Iceland, Sweden), but here are joined by Switzerland, Austria, and Australia, being above the benchmark indicator of 60 years. The USA belongs to the middle range, as does also Germany and the UK, and somewhat behind these countries we find Japan. Eastern European countries and Baltic countries are at the bottom of the European level. No developed country is rated as “bottom.” These results do not differ fundamentally from the quality of life indicators presented before.

Inequality of Subjective Well-Being in Societies

The discovery of the new dimension of subjective well-being has also led to the question of its inequality inside the countries. Analogously to income inequality, there is assumed an inequality of satisfaction (Veenhoven 2005a, b). Since each individual has their own satisfaction score, the degree of inequality can be measured and related to objective measures like income. It is argued that the inequality of a feeling is a better expression of the tensions of a society than the inequality of income which—measured by experts—is perhaps not well perceived by people (Overview 18.13).

Inequality of happiness (IOH) in developed countries 1995–2005 (IOH value: Standard deviation of four-step satisfaction scale. Source: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_hat/findingreports/RankReport2006-3.htm)

The result is that the small countries in North and Central Europe demonstrate low inequality of life satisfaction. Also Switzerland and Australia belong to the “top” group with low inequality of life satisfaction. The big countries of Europe are similar to the big non-European countries. The past socialist countries in Eastern Europe and the Baltic area have the highest standard deviation for their satisfaction scores. No developed country has a standard deviation for its perceived life quality above 3. The comparison over time shows that there is a trend toward more equality of life satisfaction though it is known that in the economic area, trends to more inequality are present. The social consequences of this newly discovered inequality should be regarded more carefully in the future.

Ecological Efficiency and Quality of Life

There are many possibilities for correlating quality of life with other variables. One ecologically oriented example is an index, called the (Un)Happy Planet Index, which is an index of human well-being and environmental impact. The basic issue being addressed is “what goes in (natural resources), and what comes out (human lives of differing length and happiness).” The political challenge, then, is whether “it is possible to live long, happy lives with a much smaller environmental impact” (Marks et al. 2006, p. 2/3). In fact, this is no pure output measure as are the indicators in previous sections. It is a measure for environmental efficiency. “It is the first ever index to combine environmental impact with well-being to measure the environmental efficiency with which country by country, people live long and happy lives” (Marks et al. 2006, p. 1). This index includes on the objective side, life expectancy, and on the subjective side, overall life satisfaction; the sum is divided by a measure for the economic footprint. This footprint is a complex concept insofar it measures how much land area is required to sustain a given population at present levels of consumption, technological development, and resource efficiency. Its accounting unit is global average hectares.

This style of thinking and counting leads to surprising results for the 180 countries of the world: Vanuatu, Colombia, and Costa Rica are—especially due to their low footprint—the best countries. The first developed countries on the scale are Malta (40), Austria (61), Iceland (64), and the position of the biggest developed country, the USA, is position 150. A country is well-off if it achieves, with a low ecological footprint, high values for length and happiness of life. These results are challenging to a high degree, and this concept should be adopted in replication studies. While the developed countries attain high values in the goal dimension, their ecological footprints are to the heaviest in the world. Thus, the message of this study is to improve ecological efficiency to reduce the ecological footprint.

Comparative Results for the Quality of Life in the Developed World

Quality of life research is engaged in an ongoing process of clarifying its measurement procedures and ultimately, defining the comparative situation of life quality in countries and on continents (Diener 2006). The conclusions in methodological respects are:

-

Quality of life is from a cross-cultural standpoint a multivaried concept and affords inevitably political and cultural decisions about its relevant components in developed societies.

-

For different views on reality, there are objective and subjective perspectives available, and both are differentiated within themselves. The decision between the preference for an objective and a subjective approach or a combination of both is never avoidable. Cross-cultural comparisons are elaborated with objective indicators (HDI, WBI, WISP), subjective indicators (OSL, ABS, PWI), and combined indicators (HLE). Each index leads to specific results for the different developed societies.

-

The various comprehensive indexes contain between one and forty subindices, and this is decisive for the results, which are obtained for the number and type of traits of developed societies and finally their similarities and differences. Only an obligatory constellation of values and criteria measured by one set of indicators would lead to a consistent evaluation of our societies. The different measurement procedures for quality of life indicators as for traditional wealth measures influence to a certain degree the statistical results (Overview 18.14).

There is significant evidence that quality of life is highest in the small North European countries; Iceland, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden show the best average value for six Quality of Life Indexes and also GDP per capita. These are the only countries which take one to three times the number one position on the different quality of life scales. This leading group of countries is joined by Austria and Ireland. The best non-European country Canada is followed by Finland and the Netherlands. Interestingly, the high-population countries (more than 50 million inhabitants) the USA, Germany, the UK, Japan, and France are at a similar level in the middle of the hierarchy. The exception is the first position of the USA in respect to GDP per capita, which documents its extraordinary economic performance. In the lower area of the quality of life scales are countries situated in the South of Europe (Italy, Spain) followed by the East (Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary) and finally the Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania). There is a clear picture of stages going down from Northern Europe to Southern Europe and then to Eastern Europe and there again up to the Baltic states, which reflects, to a certain degree, the different histories of the regions.

An explanation of this picture is also enhanced by attention to the different types of welfare states: the social democratic welfare states of Northern Europe are at the top, the conservative and liberal welfare states of Central Europe are in the middle, and the rudimentary welfare states of Southern and Eastern Europe are in the low stratum of the well-being hierarchy. Another remarkable point is that, in general, the level of well-being of the big countries (above 50 million inhabitants) is never at the top. These big countries show normally a significant heterogeneity between their regions. Consequently, there is a tendency for large countries that their average indicators for their whole area are neither at the top nor at the bottom of well-being.

The differing relative positions for the various countries confirm that economic success and quality of life are rather different dimensions and also objective and subjective measurement leads to different results. All the scales and indicators represent different views of the countries. Nevertheless, they represent structural features of the respective societies on the path of globalization, which are slowly transformed by people and politics.

Notes

- 1.

To calculate the HDI, an index is developed for each of the three dimensions, which ranges from 0 (minimum value) to 100 (maximum value). The HDI is the simple average of the three index values.

- 2.

The construction of the HWI is as a composite index, where each country is positioned in a range between 0 and 100, the best and the worst empirical value. Using benchmarks, which were developed by the author, the different countries of the world are evaluated from fair/good to bad (Prescott-Allen 2001).

- 3.

A score on the Positive Affect Scale is obtained by summing up ratings for the 5 positive affect questions; the score for the Negative Affect Scale is obtained by summing up the ratings for the 5 negative affect questions. The Affect Balance Scale score is computed by subtracting Negative Affect Scale scores from Positive Affect Scale scores. Scores range then from −5 (lowest affect balance score) to +5 (highest affect balance score).

- 4.

The list includes over 50 countries, and these can be viewed at http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/inter_wellbeing/index.htm. The international comparisons are mainly in respect to reliability and validity of the data.

- 5.

The Personal Well-Being Index is related to a theory of homeostasis of subjective well-being. According to this theory, subjective well-being is actively managed by a system that strives to maintain the individual level of happiness close to a genetically determined set point. But it is no problem to regard the concept of the PWI independent from this theoretical contribution.

References

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago: Aldine.

Camfield, L. (2004). Subjective measures of well-being in developing countries. In W. Glatzer, S. von Below, & M. Stoffregen (Eds.), Challenges for quality of life in the contemporary world. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer.

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Palant, J., Van Vugt, J., & Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: The Australian unity wellbeing index. Social Indicators Research, 64, 159–190.

Cummins, R. A., et al. (2004). The international wellbeing index: A psychometric progress report. A psychometric progress report. http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/iwbg/correspondence/2004/International-Wellbeing-Index.ppt, 10.10.2011

Cummins, R. A., et al. (2007). Australian unity wellbeing index (Report 18). Australian Centre on Quality of Life. Melbourne: Deakin University.

Diener, Ed. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 397–404.

Delhey, J. (2004). Life satisfaction in an enlarged Europe. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Dublin

Estes, R. (1984). The social progress of nations. New York: Praeger.

Estes, R. (1988). Trends in world social development—the social progress of nations 1970–1987. Westport/London: Praeger.

Estes, R. J. (1997). Social development trends in Europe 1970–1994: Development prospects for the new Europe. Social Indicators Research, 42(1), 1997.

Estes, R. (2003). At the crossroads: Development challenges of the new century. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. http://www.sp2.upenn.edu/restes/WISP2000/Table%205%20WISP%20Scores%20and%20Ranks%20For%20All%20Countries.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2011.

Glatzer, W., von Below, S., & Stoffregen, M. (2004). Challenges for quality of life in the contemporary world. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer.

http://us.oneworld.net/article/report-measures-human-development-trends-us

Halman, L. et al. (2008). Changing values and beliefs in 85 countries. Leiden: Brill.

Henderson, H. (2002). Globalization and quality of life. Talking points for the Calvert group press briefing. National Press Club, Washington, DC. http://www.hazelhenderson.com/recentPapers/Calvert%20Press%20Briefing%20tlk%20pnts.html, 10.10.2011

Human Development Report. (2007/2008). United Nations Development Programme.

Lau, A. L. D. (2005). The international wellbeing group and the international wellbeing index. http://www.rs.polyu.edu.hk/rs/peole/rsalau_IWG.htm, 04.11.2004

Lau, A. L. D., Cummins, R. A., & McPerson, W. (2005). An investigation into the cross-cultural equivalence of the personal wellbeing index. Social Indicators Research, 72, 403–430.

Maddison, A. (2001). The world economy: A millenial perspective. Paris: OECD.

Marks, N., Saaman, A., Simms, A., & Thompson, S. (2006). The (un-)happy planet—An index of human wellbeing and environmental impact. (http://www.happyplanetindex.org/public-data/files/happy-planet-index-first-global.pdf, 10.10.2011)

Noll, H. H. (2004). Social indicators- and quality-of-life research: Background, achievements and current trends. In N. Genov (Ed.), Advances in sociological knowledge over half a century (pp. 151–181). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Nussbaum, M. C., & Sen, A. (1993). The quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon.

Offer, A. (1996). Pursuit of the quality of life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prescott-Allen, R. (2001). The wellbeing of nations—a country-by-country index of quality of life and the environment. Washington/Covelo/London: Island Press.

Rapley, M. (2003). Quality of life research. London/New Dehli: Sage Publications/Thousand Oaks.

Sharpe, A. (1999). A survey of indicators of economic and social well-being. Ottawa: Centre for the Study of Living Standards.

United Nations Development Programme. (2003). Human development report 2003. Oxford: University Press, New York, Oxford.

United Nations Development Programme. (2005). Human development report 2005. New York.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht/Boston: D.Reidel.

Veenhoven, R. (1996). Happy life-expectancy—A comprehensive measure of quality-of-life in nations. Social Indicators Research, 39, 1–58.

Veenhoven, R. (2005a). http://www.worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/

Venhoven, R. (2005b). Return of inequality in modern society? Test by dispersion of life-satisfaction across time and nations. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 457–487.

Veenhoven, R. (2006). Average happiness in 95 nations 1995–2005. World Database of Happiness, RankReport 2006. worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur, 10.12.2008.

World Value Survey www.worldvaluesurvey.org

Zapf, W. (Ed.). (1987). German social report. Living conditions and subjective well-being, 1978–1984. Social indicators research, 19(1), pp. 1–171.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Netherlands

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Glatzer, W. (2012). Cross-National Comparisons of Quality of Life in Developed Nations, Including the Impact of Globalization. In: Land, K., Michalos, A., Sirgy, M. (eds) Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2421-1_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2421-1_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-2420-4

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-2421-1

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)